Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cystitis in Females Workup

Uploaded by

Lorenzo Dominick CidCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cystitis in Females Workup

Uploaded by

Lorenzo Dominick CidCopyright:

Available Formats

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

Cystitis in Females Workup

Author: John L Brusch, MD, FACP; Chief Editor: Michael Stuart Bronze, MD more...

Updated: Apr 7, 2014

Approach Considerations

In the 1980s, many experts felt that urine cultures were unnecessary in young women with probable cystitis

because almost all of these were caused by pan-susceptible isolates of Escherichia coli. Since then, however,

antibiotic resistance in uropathogenic E coli has become a significant concern. Resistance has also been emerging

among other common cystitis pathogens, including Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus saprophyticus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) resistance has reached levels as high as 20% in some communities.

Substitution of fluoroquinolones has resulted in an increase in resistance to these drugs, as well.[14]

Nevertheless, according to guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a urine

culture is not required for the initial treatment of women with a symptomatic lower urinary tract infection (UTI) with

pyuria or bacteriuria or both.[15] In a United Kingdom study, dipstick diagnosis proved more cost-effective than

positive midstream urine culture for targeting antibiotic therapy.[4]

Consider obtaining urine cultures in cases of cystitis in immunosuppressed patients and those with a recent history

of instrumentation, exposure to antibiotics, or recurrent infection. Obtaining cultures is also advisable in elderly

women, who have a high rate of upper tract involvement.

Microscopic hematuria is found in about half of cystitis cases; when found without symptoms or pyuria, it should

prompt a search for malignancy. Other possibilities to be considered in the differential diagnosis include calculi,

vasculitis, renal tuberculosis, and glomerulonephritis.

In a developing country, hematuria is suggestive of schistosomiasis. Retention of Schistosoma haematobium eggs

and formation of granulomas in the urinary tract can lead not only to hematuria but also to dysuria, bladder polyps

and ulcers, and even obstructive uropathies. Schistosomiasis can also be associated with salmonellosis and

squamous cell malignancies of the bladder.

Bacteremia is associated with pyelonephritis, corticomedullary abscesses, and perinephric abscesses.

Approximately 10-40% of patients with pyelonephritis or perinephric abscesses have positive results on blood

culture. Bacteremia is not necessarily associated with a higher morbidity or mortality in women with uncomplicated

UTI.

Cervical swabs may be indicated in cases of possible pelvic inflammatory disease.

Visual inspection of the urine is not helpful. Cloudiness of the urine is most often due to protein or crystal

presence, and malodorous urine may be due to diet or medication use.

No imaging studies are indicated in the routine evaluation of cystitis. Renal function testing is not indicated in most

episodes of UTI, but it may be helpful in patients with known urinary tract structural abnormality or renal

insufficiency. Renal function testing also may be helpful in older, particularly ill-appearing hosts or in hosts with

other complications.

A study of 196 women with painful and/or frequent urination found that most could be classified as having a low or

high risk for UTI by asking the following questions[16, 17] :

Does the patient think she has a UTI?

Is there at least considerable pain on urination?

Is there vaginal irritation?

History correctly classified 56% of patients as having a UTI risk of either less than 30% or more than 70%, and

adding urine dipstick results increased this correct classification rate to 73%. Correct classification increased to

83% when patients with intermediate risk (30-70%) after history alone underwent an additional test. The strongest

indicators of UTI were the patient's suspicion of having a UTI and a positive nitrite test.[16, 17]

Urinalysis

The most accurate method to measure pyuria is counting leukocytes in unspun fresh urine using a hemocytometer

chamber; greater than 10 white blood cells (WBCs)/mL is considered abnormal. Counts determined from a wet

mount of centrifuged urine are not reliable measures of pyuria. A noncontaminated specimen is suggested by a

lack of squamous epithelial cells. Pyuria is a sensitive (80-95%) but nonspecific (50-76%) sign of UTI.

White cell casts may be observed in conditions other than infection, and they may not be observed in all cases of

pyelonephritis. If the patient has evidence of acute infection and white cell casts are present, however, the infection

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 1 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

likely represents pyelonephritis. A spun sample (5 mL at 2000 revolutions per min [rpm] for 5 min) is best used for

evaluation of cellular casts.

Proteinuria is commonly observed in infections of the urinary tract, but the proteinuria usually is low grade. More

than 2 g of protein per 24 hours suggests glomerular disease.

Approximately 70% of patients with corticomedullary abscesses have abnormal urinalysis findings, whereas those

with renal cortical abscesses usually have normal findings. Two thirds of patients with perinephric abscesses have

an abnormal urinalysis.

Urine specimen collection

Urine specimens may be obtained by midstream clean catch, suprapubic aspiration, or catheterization.

The midstream-voided technique is as accurate as catheterization if proper technique is followed. Instruct the

woman to remove her underwear and sit facing the back of the toilet. This promotes proper positioning of the

thighs.

Instruct the patient to spread the labia with one hand and cleanse from front to back with povidone-iodine or

soaped swabs with the other hand; then pass a small amount of urine into the toilet; and finally urinate into the

specimen cup. The use of a tampon may allow a proper specimen if heavy vaginal bleeding or discharge is

present.

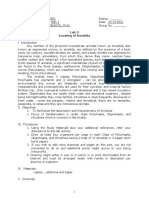

Midstream urine specimens may become contaminated, particularly if the woman has difficulty spreading and

maintaining separation of the labia. The presence of squamous cells and lactobacilli on urinalysis suggests

contamination or colonization (see image below). Catheterization may be needed in some women to obtain a clean

specimen, although it poses the risk of iatrogenic infection.[18]

Lactobacilli and a squamous epithelial cell are evident on this vaginal smear. The presence of squamous cells and lactobacilli on

urinalysis suggests contamination or colonization. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Mike Miller

Although the use of midstream urine specimens is widely advocated, one randomized trial in young women

showed that the rate of contamination was nearly identical among those who used midstream clean-catch

technique and those who urinated into a container without cleansing the perineum or discarding the first urine

output. Use of a vaginal tampon in addition to clean-catch technique had no significant effect on the contamination

rate.[19]

Dipstick testing

Dipstick testing should include glucose, protein, blood, nitrite, and leukocyte esterase. Leukocyte esterase is a

dipstick test that can rapidly screen for pyuria; it is 57-96% sensitive and 94-98% specific for identifying pyuria.

Given this broad range of sensitivity, it is important to consider the possibility of false-positive results, particularly

with asymptomatic patients undergoing evaluation for recurrent UTI.

Pyuria, as indicated by a positive result of the leukocyte esterase dipstick test, is found in the vast majority of

patients with UTI. This is an exceedingly useful screening examination that can be performed promptly in any ED

setting. If pyuria is absent, the diagnosis of UTI should be questioned until urine culture results become available.

In a United Kingdom study, dipstick diagnosis based on findings of nitrite or both leukocyte esterase and blood was

77% sensitive and 79% specific, with a positive predictive value of 81% and a negative predictive value of 65%.[4]

Diagnosis on clinical grounds proved less sensitive.

Urine microscopy

A microscopic evaluation of the urine sample for WBC counts, RBC counts, and cellular or hyaline casts should be

performed. In the office, a combination of clinical symptoms with dipstick and microscopic analysis showing pyuria

and/or positive nitrite and leukocyte esterase tests can be used as presumptive evidence of UTI.

Low-level pyuria (6-20 WBCs per high-power field [hpf] microscopy on a centrifuged specimen) may be associated

with an unacceptable level of false-negative results with the leukocyte esterase dipstick test, as Propp et al found

in an ED setting.[20]

In females with appropriate symptoms and examination findings suggestive of UTI, urine microscopy may be

indicated despite a negative result of the leukocyte esterase dipstick test. Current emphasis in the diagnosis of UTI

rests with the detection of pyuria. As noted, a positive leukocyte esterase dipstick test suffices in most instances.

According to Stamm et al, levels of pyuria as low as 2-5 WBCs/hpf in a centrifuged specimen are important in

females with appropriate symptoms. The presence of bacteriuria is significant. However, the presence of

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 2 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

numerous squamous epithelial cells raises the possibility of contamination.[18] Low-level or, occasionally, frank

hematuria may be noted in otherwise typical UTI; however, its positive predictive value is poor.

Nitrate test

Nitrate tests detect the products of nitrate reductase, an enzyme produced by many bacterial species. These

products are not present normally unless a UTI exists. This test has a sensitivity and specificity of 22% and 94100%, respectively. The low sensitivity has been attributed to enzyme-deficient bacteria causing infection or lowgrade bacteriuria.

A positive result on the nitrate test is highly specific for UTI, typically because of urease-splitting organisms, such

as Proteus species and, occasionally, E coli; however, it is very insensitive as a screening tool, as only 25% of

patients with UTI have a positive nitrate test result.

Urine Culture

Urine culture remains the criterion standard for the diagnosis of UTI. Collected urine should be sent for culture

immediately; if not, it should be refrigerated at 4C. Two culture techniques (dip slide, agar) are widely used and

accurate.

The 2010 Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) consensus limits for cystitis and pyelonephritis in women

are more than 1000 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL and more than 10,000 CFU/mL, respectively, for clean-catch

midstream urine specimens. Historically, the definition of UTI was based on the finding at culture of 100,000

CFU/mL of a single organism. However, this misses up to 50% of symptomatic infections, so the lower colony rate

of greater than 1000 CFU/mL is now accepted.[21]

The definition of asymptomatic bacteriuria still uses the historical threshold. Asymptomatic bacteruria in a female is

defined as a urine culture (clean-catch or catheterized specimen) growing greater than 100,000 CFU/mL in an

asymptomatic individual.

Note that any amount of uropathogen grown in culture from a suprapubic aspirate should be considered evidence

of a UTI. Approximately 40% of patients with perinephric abscesses have sterile urine cultures.

An uncomplicated UTI (cystitis) does not require a urine culture unless the woman has experienced a failure of

empiric therapy. Obtain a urine culture in patients suspected of having an upper UTI or a complicated UTI, as well

in those in whom initial treatment fails.

If the patient has had a UTI within the last month, relapse is probably caused by the same organism. Relapse

represents treatment failure. Reinfection occurs in 1-6 months and usually is due to a different organism (or

serotype of the same organism). Obtain a urine culture for patients who are reinfected.

If a Gram stain of an uncentrifuged, clean-catch, midstream urine specimen reveals the presence of 1 bacterium

per oil-immersion field, it represents 10,000 bacteria/mL of urine. A specimen (5 mL) that has been centrifuged for

5 minutes at 2000 rpm and examined under high power after Gram staining will identify lower numbers. In general,

a Gram stain has a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 88%.

Complete Blood Cell Count

A CBC is not helpful in differentiating upper from lower UTI or in making decisions regarding admission. However,

significant leukopenia in hosts who are older or immunocompromised may be an ominous finding.

The WBC count may or may not be elevated in patients with uncomplicated UTI, but it is usually elevated in

patients with complicated UTIs. Patients with complicated UTIs may have anemia; for example, anemia is

observed in 40% of patients with perinephric abscesses.

Diagnostic Catheterization

Catheterization is indicated if the patient cannot void spontaneously, if the patient is too debilitated or immobilized,

or if obesity prevents the patient from obtaining a suitable specimen. Measurement of postvoiding residual urine

volume by catheterization may reveal urinary retention in a host with a defective bladder-emptying mechanism.

Measurement of the postvoid residual volume should be strongly considered in all patients who require hospitallevel care. Handheld portable bladder scans may also be used as a noninvasive alternative.

Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advise that in acute care hospital settings,

aseptic technique and sterile equipment for catheter insertion must be used to minimize the risk of catheterassociated UTI. Only properly trained individuals who are skilled in the correct technique of aseptic catheter

insertion and maintenance should take on this task.[22]

For more information on this procedure, see the Medscape Reference article Urethral Catheterization in Women.

Infection in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury

Diagnosing a UTI in a patient with a spinal cord injury is difficult. In patients with SCI, signs and symptoms

suggestive of a UTI are malodorous and cloudy urine, muscular spasticity, fatigue, fevers, chills, and autonomic

instability.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 3 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

In these patients, suprapubic aspiration of the bladder is the criterion standard for diagnosing a UTI, although it is

not performed often in clinical practice.

For more information on this topic, see the Medscape Reference article Urinary Tract Infections in Patients with

Spinal Cord Injury.

Infection in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus

Patients with diabetes are at risk for complicated UTIs, which may include renal and perirenal abscess,

emphysematous pyelonephritis, emphysematous cystitis, fungal infections, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis,

and papillary necrosis.

For more information, see the Medscape Reference topic Urinary Tract Infections in Diabetes Mellitus.

Cystitis Caused by Candida

Cystitis caused by Candida is clinically similar to cystitis from other pathogens. The presence of fungus in the urine

should be verified by repeating the urinalysis and urine culture. Other features of diagnosis are as follows[23] :

Pyuria is a nonspecific finding

C glabrata may be differentiated from other species by morphology

Candida casts in the urine indicate renal candidiasis but are rarely seen

Colony counts have not proved diagnostically useful

Ultrasonography of the kidneys and collecting systems is the preferred initial study in symptomatic or critically ill

patients with candiduria, but computed tomography is better for detecting pyelonephritis or perinephric abscess.[23]

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author

John L Brusch, MD, FACP Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Consulting Staff,

Department of Medicine and Infectious Disease Service, Cambridge Health Alliance

John L Brusch, MD, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians and

Infectious Diseases Society of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Coauthor(s)

Mary F Bavaro, MD Fellowship Director, Division of Infectious Disease, Navy Medical Center, San Diego

Mary F Bavaro, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians and

Infectious Diseases Society of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Burke A Cunha, MD Professor of Medicine, State University of New York School of Medicine at Stony Brook;

Chief, Infectious Disease Division, Winthrop-University Hospital

Burke A Cunha, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Chest Physicians,

American College of Physicians, and Infectious Diseases Society of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Jeffrey M Tessier, MD Assistant Professor, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine,

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Jeffrey M Tessier, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians-American

Society of Internal Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD David Ross Boyd Professor and Chairman, Department of Medicine, Stewart G

Wolf Endowed Chair in Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Science

Center; Master of the American College of Physicians; Fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American

College of Physicians, American Medical Association, Association of Professors of Medicine, Infectious

Diseases Society of America, Oklahoma State Medical Association, and Southern Society for Clinical

Investigation

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP Professor of Emergency Medicine, Northeastern Ohio Universities

College of Medicine and Pharmacy; Attending Faculty, Akron General Medical Center

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 4 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of

Emergency Physicians, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, National Association of EMS

Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Pamela L Dyne, MD Professor of Clinical Medicine/Emergency Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

David Geffen School of Medicine; Attending Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Olive View-UCLA

Medical Center

Pamela L Dyne, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency

Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

David S Howes, MD Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics, Section Chief and Emergency Medicine Residency

Program Director, University of Chicago Division of the Biological Sciences, The Pritzker School of Medicine

David S Howes, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency

Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of

Internal Medicine, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Elicia S Kennedy, MD Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Arkansas

for Medical Sciences

Elicia S Kennedy, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency

Physicians and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Klaus-Dieter Lessnau, MD, FCCP Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, New York University School of

Medicine; Medical Director, Pulmonary Physiology Laboratory; Director of Research in Pulmonary Medicine,

Department of Medicine, Section of Pulmonary Medicine, Lenox Hill Hospital

Klaus-Dieter Lessnau, MD, FCCP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Chest

Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Medical Association, American Thoracic Society, and

Society of Critical Care Medicine

Disclosure: Sepracor None None

Allison M Loynd, DO Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wayne State University School

of Medicine, Detroit Receiving Hospital

Allison M Loynd, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency

Physicians, American Medical Association, and Emergency Medicine Residents Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mark Jeffrey Noble, MD Consulting Staff, Urologic Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Mark Jeffrey Noble, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons,

American Medical Association, American Urological Association, Kansas Medical Society, Sigma Xi, Society of

University Urologists, and Southwest Oncology Group

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Adam J Rosh, MD Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Detroit Receiving Hospital, Wayne

State University School of Medicine

Adam J Rosh, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine,

American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joseph A Salomone III, MD Associate Professor and Attending Staff, Truman Medical Centers, University of

Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; EMS Medical Director, Kansas City, Missouri

Joseph A Salomone III, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency

Medicine, National Association of EMS Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Richard H Sinert, DO Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine,

Research Director, State University of New York College of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Department of

Emergency Medicine, Kings County Hospital Center

Richard H Sinert, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians and

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 5 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center

College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

Mark Zwanger, MD, MBA Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jefferson Medical College

of Thomas Jefferson University

Mark Zwanger, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency

Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and American Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

References

1. [Guideline] Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the

treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious

Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin

Infect Dis. Mar 2011;52(5):e103-20. [Medline]. [Full Text].

2. [Guideline] Wagenlehner FM, Schmiemann G, Hoyme U, Fnfstck R, Hummers-Pradier E, Kaase M, et

al. [National S3 guideline on uncomplicated urinary tract infection: recommendations for treatment and

management of uncomplicated community-acquired bacterial urinary tract infections in adult patients].

Urologe A. Feb 2011;50(2):153-69. [Medline]. [Full Text].

3. Abrahamian FM, Moran GJ, Talan DA. Urinary tract infections in the emergency department. Infect Dis

Clin North Am. Mar 2008;22(1):73-87, vi. [Medline].

4. Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Moore M, Lowes JA, et al. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in

urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational

cohort and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess. Mar 2009;13(19):iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-73. [Medline].

5. Lane DR, Takhar SS. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis. Emerg Med

Clin North Am. Aug 2011;29(3):539-52. [Medline].

6. Czaja CA, Stamm WE, Stapleton AE, et al. Prospective cohort study of microbial and inflammatory events

immediately preceding Escherichia coli recurrent urinary tract infection in women. J Infect Dis. Aug 15

2009;200(4):528-36. [Medline].

7. Kanj SS, Kanafani ZA. Current concepts in antimicrobial therapy against resistant gram-negative

organisms: extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant

Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mayo Clin Proc. Mar

2011;86(3):250-9. [Medline]. [Full Text].

8. [Guideline] Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheterassociated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the

Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. Mar 1 2010;50(5):625-63. [Medline]. [Full Text].

9. Tiemstra JD, Chico PD, Pela E. Genitourinary infections after a routine pelvic exam. J Am Board Fam

Med. May-Jun 2011;24(3):296-303. [Medline].

10. Hsiao CJ, Cherry DK, Beatty PC, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007

summary. Natl Health Stat Report. Nov 3 2010;1-32. [Medline].

11. Naber KG, Schito G, Botto H, Palou J, Mazzei T. Surveillance study in Europe and Brazil on clinical

aspects and Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology in Females with Cystitis (ARESC): implications for

empiric therapy. Eur Urol. Nov 2008;54(5):1164-75. [Medline].

12. Little P, Merriman R, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Lowes JA, et al. Presentation, pattern, and natural

course of severe symptoms, and role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among patients presenting

with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care: observational study. BMJ. Feb 5

2010;340:b5633. [Medline]. [Full Text].

13. Molander U, Arvidsson L, Milsom I, Sandberg T. A longitudinal cohort study of elderly women with urinary

tract infections. Maturitas. Feb 15 2000;34(2):127-31. [Medline].

14. Johnson L, Sabel A, Burman WJ, Everhart RM, Rome M, MacKenzie TD, et al. Emergence of

fluoroquinolone resistance in outpatient urinary Escherichia coli isolates. Am J Med. Oct

2008;121(10):876-84. [Medline].

15. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). 2008. Treatment of urinary tract infections

in nonpregnant women. Available at http://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=12628. Accessed September

22, 2010.

16. Barclay L. Urinary Tract Infection: 3 Questions Aid Diagnosis in Women. Medscape Medical News.

Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/810667. Accessed September 16, 2013.

17. Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, Ter Riet G. Toward a simple diagnostic index for

acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Ann Fam Med. Sep-Oct 2013;11(5):442-51. [Medline]. [Full

Text].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 6 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

18. Schaeffer AJ, Schaeffer EM. Infections of the Urinary Tract. In: McDougal WS, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, et

al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:46-55.

19. Lifshitz E, Kramer L. Outpatient urine culture: does collection technique matter?. Arch Intern Med. Sep 11

2000;160(16):2537-40. [Medline].

20. Propp DA, Weber D, Ciesla ML. Reliability of a urine dipstick in emergency department patients. Ann

Emerg Med. May 1989;18(5):560-3. [Medline].

21. Mehnert-Kay SA. Diagnosis and Management of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections. American

Family Physician [serial online]. August 1, 2005;27/No.3:1-9. Accessed September 22, 2010. Available at

http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0801/p451.html.

22. [Guideline] Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA. Guideline for prevention of

catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Apr 2010;31(4):319-26.

[Medline]. [Full Text].

23. Kauffman CA, Fisher JF, Sobel JD, Newman CA. Candida urinary tract infections--diagnosis. Clin Infect

Dis. May 2011;52 Suppl 6:S452-6. [Medline].

24. Falagas ME, Kotsantis IK, Vouloumanou EK, Rafailidis PI. Antibiotics versus placebo in the treatment of

women with uncomplicated cystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Infect. Feb

2009;58(2):91-102. [Medline].

25. Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol. Dec 2010;7(12):653-60. [Medline].

26. Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Lowes JA, et al. Effectiveness of five different

approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. Feb 5

2010;340:c199. [Medline]. [Full Text].

27. Christiaens TC, De Meyere M, Verschraegen G, Peersman W, Heytens S, De Maeseneer JM.

Randomised controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary

tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract. Sep 2002;52(482):729-34. [Medline]. [Full Text].

28. Bleidorn J, Ggyor I, Kochen MM, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Symptomatic treatment

(ibuprofen) or antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) for uncomplicated urinary tract infection?--results of a randomized

controlled pilot trial. BMC Med. May 26 2010;8:30. [Medline]. [Full Text].

29. Olson RP, Harrell LJ, Kaye KS. Antibiotic resistance in urinary isolates of Escherichia coli from college

women with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. Mar 2009;53(3):1285-6. [Medline].

[Full Text].

30. McKinnell JA, Stollenwerk NS, Jung CW, Miller LG. Nitrofurantoin compares favorably to recommended

agents as empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a decision and cost analysis.

Mayo Clin Proc. Jun 2011;86(6):480-8. [Medline]. [Full Text].

31. Falagas ME, Vouloumanou EK, Togias AG, Karadima M, Kapaskelis AM, Rafailidis PI, et al. Fosfomycin

versus other antibiotics for the treatment of cystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J

Antimicrob Chemother. Sep 2010;65(9):1862-77. [Medline]. [Full Text].

32. [Guideline] Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases

Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin

Infect Dis. Mar 1 2005;40(5):643-54. [Medline]. [Full Text].

33. Dalal S, Nicolle L, Marrs CF, Zhang L, Harding G, Foxman B. Long-term Escherichia coli asymptomatic

bacteriuria among women with diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. Aug 15 2009;49(4):491-7. [Medline]. [Full

Text].

34. Beerepoot MA, ter Riet G, Nys S, et al. Cranberries vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: a

randomized double-blind noninferiority trial in premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. Jul 25

2011;171(14):1270-8. [Medline].

35. Jepson RG, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

Jan 23 2008;CD001321. [Medline].

36. Tempera G, Corsello S, Genovese C, Caruso FE, Nicolosi D. Inhibitory activity of cranberry extract on the

bacterial adhesiveness in the urine of women: an ex-vivo study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. Apr-Jun

2010;23(2):611-8. [Medline].

37. De Vita D, Giordano S. Effectiveness of intravesical hyaluronic acid/chondroitin sulfate in recurrent

bacterial cystitis: a randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. Dec 2012;23(12):1707-13. [Medline].

38. van der Starre WE, van Nieuwkoop C, Paltansing S, et al. Risk factors for fluoroquinolone-resistant

Escherichia coli in adults with community-onset febrile urinary tract infection. J Antimicrob Chemother.

Mar 2011;66(3):650-6. [Medline].

39. Cunha BA. Prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections: nitrofurantoin, not trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole or cranberry juice. Arch Intern Med. Jan 9 2012;172(1):82; author reply 82-3. [Medline].

40. Cunha BA, Schoch PE, Hage JR. Nitrofurantoin: preferred empiric therapy for community-acquired lower

urinary tract infections. Mayo Clin Proc. Dec 2011;86(12):1243-4; author reply 1244. [Medline]. [Full Text].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 7 of 8

Cystitis in Females Workup

3/2/15, 3:48 PM

41. Fischer HD, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Kopp A, Laupacis A. Hemorrhage during warfarin therapy

associated with cotrimoxazole and other urinary tract anti-infective agents: a population-based study. Arch

Intern Med. Apr 12 2010;170(7):617-21. [Medline].

42. Hand L. Urinary Infections: Report Offers Long-Needed Clarity. Medscape [serial online]. Available at

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814305. Accessed November 18, 2013.

43. Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Cox ME, Stapleton AE. Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in

premenopausal women. N Engl J Med. Nov 14 2013;369(20):1883-91. [Medline].

44. Leydon GM, Turner S, Smith H, Little P. Women's views about management and cause of urinary tract

infection: qualitative interview study. BMJ. Feb 5 2010;340:c279. [Medline]. [Full Text].

45. Pinson AG, Philbrick JT, Lindbeck GH, Schorling JB. ED management of acute pyelonephritis in women: a

cohort study. Am J Emerg Med. May 1994;12(3):271-8. [Medline].

46. Turner D, Little P, Raftery J, Turner S, Smith H, Rumsby K, et al. Cost effectiveness of management

strategies for urinary tract infections: results from randomised controlled trial. BMJ. Feb 5 2010;340:c346.

[Medline]. [Full Text].

Medscape Reference 2011 WebMD, LLC

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/233101-workup

Page 8 of 8

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- B17M2L8 - Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument7 pagesB17M2L8 - Gestational Diabetes MellitusLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- KAP On Foreign Health Care System Similar To NBBDocument1 pageKAP On Foreign Health Care System Similar To NBBLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- Cid SGDDocument3 pagesCid SGDLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- 2018 Ctagbt Reg FormDocument1 page2018 Ctagbt Reg FormLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- Answer SheetDocument3 pagesAnswer SheetLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- Score Sheet BadmintonDocument2 pagesScore Sheet BadmintonLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- Professional Version Professional Version: MSD MSD Manual ManualDocument2 pagesProfessional Version Professional Version: MSD MSD Manual ManualLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- PCol Ni Cid PDFDocument1 pagePCol Ni Cid PDFLorenzo Dominick CidNo ratings yet

- Physical Pharmacy NotesDocument10 pagesPhysical Pharmacy NotesLorenzo Dominick Cid100% (8)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ADDC Construction QuestionairesDocument19 pagesADDC Construction QuestionairesUsman Arif100% (1)

- Manual Del GVMapper v3 3 PDFDocument102 pagesManual Del GVMapper v3 3 PDFguanatosNo ratings yet

- Heradesign Brochure 2008Document72 pagesHeradesign Brochure 2008Surinder SinghNo ratings yet

- 19 - Speed, Velocity and Acceleration (Answers)Document4 pages19 - Speed, Velocity and Acceleration (Answers)keyur.gala100% (1)

- Ridge regression biased estimates nonorthogonal problemsDocument14 pagesRidge regression biased estimates nonorthogonal problemsGHULAM MURTAZANo ratings yet

- Three Bucket Method & Food ServiceDocument4 pagesThree Bucket Method & Food Servicerose zandrea demasisNo ratings yet

- Forklift Truck Risk AssessmentDocument2 pagesForklift Truck Risk AssessmentAshis Das100% (1)

- Sony HCD-GTX999 PDFDocument86 pagesSony HCD-GTX999 PDFMarcosAlves100% (1)

- 2.gantry Rotation Safety CheckDocument2 pages2.gantry Rotation Safety CheckLê Hồ Nguyên ĐăngNo ratings yet

- AOAC 2012.11 Vitamin DDocument3 pagesAOAC 2012.11 Vitamin DPankaj BudhlakotiNo ratings yet

- Civil ServiceDocument46 pagesCivil ServiceLester Josh SalvidarNo ratings yet

- CSC-1321 Gateway User Guide: Downloaded From Manuals Search EngineDocument48 pagesCSC-1321 Gateway User Guide: Downloaded From Manuals Search EngineKislan MislaNo ratings yet

- Hedging Techniques in Academic WritingDocument11 pagesHedging Techniques in Academic WritingÛbř ÖňNo ratings yet

- The Relevance of Vivekananda S Thought IDocument16 pagesThe Relevance of Vivekananda S Thought IJaiyansh VatsNo ratings yet

- 2 - Alaska - WorksheetsDocument7 pages2 - Alaska - WorksheetsTamni MajmuniNo ratings yet

- Abiotic and Biotic Factors DFDocument2 pagesAbiotic and Biotic Factors DFgiselleNo ratings yet

- AMYLOIDOSISDocument22 pagesAMYLOIDOSISMohan ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Rincon Dueling RigbyDocument5 pagesRincon Dueling Rigbytootalldean100% (1)

- Symbols For Signalling Circuit DiagramsDocument27 pagesSymbols For Signalling Circuit DiagramsrobievNo ratings yet

- 2290 PDFDocument222 pages2290 PDFmittupatel190785No ratings yet

- Goat Milk Marketing Feasibility Study Report - Only For ReferenceDocument40 pagesGoat Milk Marketing Feasibility Study Report - Only For ReferenceSurajSinghalNo ratings yet

- Patient Positioning: Complete Guide For Nurses: Marjo S. Malabanan, R.N.,M.NDocument43 pagesPatient Positioning: Complete Guide For Nurses: Marjo S. Malabanan, R.N.,M.NMercy Anne EcatNo ratings yet

- NASA Technical Mem Randum: E-Flutter N78Document17 pagesNASA Technical Mem Randum: E-Flutter N78gfsdg dfgNo ratings yet

- Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife CenterDocument7 pagesNinoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife CenterNinia Richelle Angela AgaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Document9 pagesWelcome To International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDNo ratings yet

- Knowing Annelida: Earthworms, Leeches and Marine WormsDocument4 pagesKnowing Annelida: Earthworms, Leeches and Marine WormsCherry Mae AdlawonNo ratings yet

- Pemanfaatan Limbah Spanduk Plastik (Flexy Banner) Menjadi Produk Dekorasi RuanganDocument6 pagesPemanfaatan Limbah Spanduk Plastik (Flexy Banner) Menjadi Produk Dekorasi RuanganErvan Maulana IlyasNo ratings yet

- Procedure for safely changing LWCV assembly with torques over 30,000 ft-lbsDocument2 pagesProcedure for safely changing LWCV assembly with torques over 30,000 ft-lbsnjava1978No ratings yet

- Com Statement (HT APFC22 - 02)Document2 pagesCom Statement (HT APFC22 - 02)SOUMENNo ratings yet

- Ethics Module 2 - NotesDocument1 pageEthics Module 2 - Notesanon_137579236No ratings yet