Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fundamentalism in The Modern World

Uploaded by

Jackly SalimiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fundamentalism in The Modern World

Uploaded by

Jackly SalimiCopyright:

Available Formats

Russian Social Science Review, vol. 44, no. 3, MayJune 2003, pp. 4162.

2003 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN 10611428/2003 $9.50 + 0.00.

IRINA V. KUDRIASHOVA

Fundamentalism in the

Modern World

In history, all clocks run forward.

Melvin Lasky, Utopia and Revolution

The return of the religious factor to politics in the form of fundamentalism is a theme that is particularly relevant today, in policy

decisions as in scholarly discussions and literature. The problems

are especially acute and alarming when fundamentalism (to be

more precise, its militarized extremist wing) causes suffering and

death. Then this phenomenon is identified in the public mind with

terrorism, medieval obscurantism, and fanaticism.

The word fundamentalism was first used in the United States

to characterize certain Christian evangelical groups (primarily

Calvinists, Presbyterians, and Baptists) in the second half of the

nineteenth century. Later it was applied to anti-Darwinists during

the [Scopes] monkey trial of the 1920s. [See, for example,

Sagadeev, 1993, p. 57; and Miloslavskii, 1999, pp. 910.] In

190915 several issues of a bulletin entitled The Fundamentals

English translation 2003 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc., from the Russian text 2002

by Polis [Politicheskie issledovaniia]. Fundamentalizm v prostranstve

sovremennogo mira, Polis, 2002, no. 1, pp. 6677.

Irina Vladimirovna Kudriashova is an assistant professor in the Department

of Comparative Politics, Moscow State Institute of International Relations

(MGIMO); she holds a candidates degree in political science.

The quotation from Melvin Lasky is retranslated from the Russian.Ed.

41

42 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

were published, which reinforced the name. Only later was the

term used by Western scholars in studying Islam, Judaism, and

other religions. In the process it was often interpreted very broadly

to mean a return to the origins of religious and civilizational unity

and as the derivation of religious and political principles from an

eternally sacred text. Nowadays fundamentalism is used to describe the theoretical and practical activity of numerous political

religious movements and organizations (Islamic, Judaic, Protestant,

Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Hindu, and Buddhist), which are

active in Southeastern and Central Asia, in Northern Africa, in the

Near East, in Europe, and in the United Statesin a word, almost

everywhere. The extent of the process and nations involvement in

it make fundamentalism not only an influential factor in but also a

subject [subekt] of politics.

It is interesting to note that the controversy regarding the definition of fundamentalism has a more than linguistic significance.

Various termsfundamentalism, religious revival, Puritanism,

renaissance, integrism [extreme traditionalismEd.], revivalism,

religious radicalism, millenarianism, and othershighlight various aspects of the phenomenon. For example, the first type of fundamentalismthe original Protestant typeregarded the Bible

as an embodiment of original purity and a guide to this world

activity; that is, it signified a return to the roots, to the foundation.

Integrism (from the French intgritintegrity, wholeness, implying purity and honesty) emphasizes communal unity and continuity based on religious and moral values, whereas revivalism

(from the English to revive, meaning to restore or to renew)

emphasizes the recurrent nature of the phenomenon. Later, Western scholars applied these concepts to Islam, but the secularized

languages of the West and Western historical parallels cannot provide appropriate analogies for the realities of the non-Western

world. In Arabic, the phenomenon is most frequently defined as

follows: al-baas al-islami (Islamic revival); as-sakhwah alislamiyyah (Islamic awakening); ihya ad-din (a revival of religion);

and al-usuliyyah al-islamiyyah (Islamic fundamentalism). The last

term (derived from usul ad-din, which literally means fundamentals

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 43

of a religion [Ar-Raid 1964: 155]) seems to be the most precise.

It implies adherence to the doctrines of faith, to the original principles of the Islamic polity (umma), and to the fundamental tenets

governing the legitimacy of power (sharia). I note here that, as

understood at present, the formula emphasizes the political dimensions rather than the religious aspect of fundamentalism. The concept of salafiyyah (denoting those who advocate a return to the

origins of Islam, to the norms of life and institutions of the righteous ancestors (as-salaf) [see Sagadeev, 1987, p. 11]) is used in

a similar sense. As for the term Islamism, which is sometimes

confused with Islam as a whole, some scholars apply it not so

much to the sphere of social thought as to the sphere of political

action [see Malashenko, 1997].

The increasingly strong embrace of religiouscivilizational unity

as a source of self-identification and new group loyalties is one of

the most important global tendencies in social development at the

end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century.

In its developed form fundamentalism is a product of the present,

although the tendency to reconstruct a golden age characterized

the axis civilizations during earlier periods as well. A distinctive

feature of modern fundamentalism is the conviction that politics

is primary, even if it is directed by a total religious worldview.

Fundamentalism achieves its highest development where there is

belief that the heavenly can be realized in the mundanethat is,

that salvation can be achieved both in this world and in the next

(which dramatically increases the amount of attention directed at

reforming existing sociopolitical institutions)where the relative

significance of the doctrine is high, and where no one social institution or group holds a monopoly on access to the sacred. The last

is connected primarily with the existence of a sacred book, open

to all believers and the ultimate source of authority (as in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). On the whole, fundamentalist trends

can be subdivided into two types: (a) those based on the Abrahamic

religions of the Book; and (b) the nationalistic derivatives of

Hinduism and Buddhism, which do not have a distinct set of sacred canons.

44 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

Regardless of all the diversity among fundamentalist movements,

primarily the result of differences in ontological concepts, a profound similarity can be observed among individual versions in the

significance given to politics and to historical experience: all these

variants aim to affirm the religious authenticity of the modern

world. But why is the return to religious ideology taking place

now? Does this reflect the eternal conflict of religion, philosophy,

and science, or does it represent something more significant? What

underlies the phenomenon? Is it a mixture of mystical impulses

with claims to rationality or a force capable of pushing humanity

into a specific new set of circumstances that are not yet visible?

The disintegration of the socialist system at the end of the twentieth century resulted, among other things, in the destruction of

the ideological opposition of liberalismsocialism. Without this

opposition, a significant part of humanity found itself in a situation of painful spiritual uncertainty, with no hope for a triumph of

justice in the wonderful, beautiful faraway world. During the

age of globalization, the world has become a smaller, more open

place. But it turned out that not everybody could enter this new

world on equal terms: altruism is inherently not a characteristic of

modernity. The gaps in economic development and the aggressive

penetration of [Western] mass culture have practically deprived

peripheral countries of the opportunity to overcome the cultural

and political divide and to preserve their civilizational foundations. A

huge amount of socio-psychological energy has been released that

cannot be channeled through models of rational adaptation to an

environment characterized by unequal partnership. This crucial

point has sharpened demands to search for different criteria and to

change ideological and value precepts at the elite and mass levels.

In the countries of the center the appeal to overcome disunity and

individualism and the call to spiritualize life in the too rational

world by returning to traditional family values, love of ones motherland, and God have acquired special importance.

Having identified the most general causes governing the development of fundamentalism, I focus on specific factors that determine the rise and specific nature of its various versions.

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 45

The specific nature of Islamic fundamentalism is determined

by the very tight links between Islam and the political and social

organization, as well as the solidarity, of the Muslim community.

Its rise was caused by the crisis of nationalism as an ideology of

liberation and by the mobilization stimulated by ineffective revolutionary development programs and was aggravated by extreme social

stratification. It was also based on the failure of borrowed ideologies,

the declining legitimacy of the authorities, the use of religious

motives and symbols as auxiliary elements in the contest among the

political elite, and the foreign activity of Muslim organizations.

The rise of Judaic fundamentalism was furthered by the following factors: the tightening of the criteria for membership in the

national community (thus, a person who is considered Jewish in

accordance with Israels state law may not be considered Jewish

in terms of religious law); the need to preserve the historic continuity of the Jewish community and the definition of Israel itself

(in conjunction with the biblical Eretz Yisrael); and the restarting

of the Middle East peace process after the Camp David Accords.

According to A.B. Volkov, contemporary Judaic fundamentalists

see the doctrine of the Chosen People and the Almightys gift of

the land of Palestine to Jews for eternity as the basis of their whole

ideological and political program [Volkov, 1999, p. 24]. At the same

time, modern-day Israel provides an especially vivid example of the

variable nature of fundamentalist thinking: thus, the ultranationalist

organization Gush Emunim (The Bloc of the Faithful), which implements intensive settlement of land in the areas bordering on Jordan

(the historical territory of Judea and Samaria), and the anti-Zionist

Haredim coexist in the country [see Eizenshtadt, 1994, p. 37].

Protestant fundamentalism is based on Puritan and conservative traditions going back to the eighteenth century (the recognition of the absolute truth of Holy Scripture and the acceptance of

the Bible as historical fact) and on its view of the American state

as a new Israel on which the salvation of other nations depends.

Protestant fundamentalism is widespread in the United States

[Haynes, 1995, p. 23], where millions of its followers advocate

the original Christian values. It also includes groups practicing

46 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

radical anti-Semitism, such as Christian Identity. Such groups believe that the world is divided into Adams descendantswhite

people, or genuine Israelitesand Satans childrenJews and

other impure people [see Tuvinov, 2001].

Catholic fundamentalism is rooted in the ideological traditions

of the counterrevolutionary criticism of the world that emerged

after 1789. The most important tenets of Catholic conservatism

against modernization, liberalism, and socialism were formulated

at the beginning of the twentieth century by Pope Pius X. Before

the Second Vatican Council (1962), integrism (this is the term that

French scholars most frequently use to denote this type of fundamentalism) remained an antimodernist tendency within the Church

supported by the Papal Curia and the episcopacy in Italy, Spain,

and especially Latin America. Today it can be defined as a theological and political movement that regards the liturgical reforms

and the theological quest of the Roman Catholic Church as heretical (it interprets ecumenism as syncretism) and considers itself

the only true voice of religious doctrine. The most influential

integrist organizations include the Society of St. Pius X, founded

by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre of France (19051993) in 1970.1

To this category of fundamentalists, the ideal Catholic state would

be the social reign of Christ, in which church law would become

state law, although the state would be governed by representatives

of the secular power with the support and counsel of the Church

and would be based on nationalism, the principle of mutual utility, the solidarity of corporate groups, and the charity system [see

Camus, 1990, pp. 6768]. This explains the influence of the group

Opus Dei (Gods Work) on the policies of such dictators as

Franco, Salazar, Peron, Stroessner, and Pinochet.

The new right movement in the United States, which has been

growing since the end of the 1970s, unites Protestant and Jewish

Orthodox believers and Catholic integrists. The three largest organizationsJerry Falwells Moral Majority, Robert Grants Christian

Voice, and Ed MacAteers [National] Religious Round Table

were created in 1979, in time for the [1980] presidential election.

Their manifesto was based on Falwells famous theses, the most

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 47

important of which is the recognition that it is Americas destiny

to create a nation to the glory of God [Cerillo and Dempster,

1989, pp. 10912, 13943]. The above-mentioned organizations

rely on television preachers efficiently using the mass media to

mobilize believers against the spread of the anti-Christian religion of secular humanism in sociopolitical life.

Finally, the sources of Orthodox Christian fundamentalism lie

in the tendency to make absolutes out of certain historical, cultural,

and political traditionsfor example, monarchism, communitarianism (sobornost ), and spontaneous collectivism. Russian Orthodox Christian fundamentalism is characterized by attempts to

improve the status of the Russian nation and strengthen Russian

statehood; by radical anticommunist sentiment; and by disapproval

of steps to normalize relations between the Western and the Eastern churches. In Russia, too, several types of fundamentalism coexist: some (including the Christian Patriotic Union [Khristianskii

patrioticheskii soiuz] and the Russian National Assembly [Russkii

natsionalnyi sobor]) emphasize the Orthodox Christian interpretation of Russian nationalism (that is, [the link between] Russian statehood and Orthodox Christian spirituality), whereas others focus

on the struggle to purify Orthodox Christianity as a religion. For

example, documents of the Christian Revival Union list its most important goals as the following: the exposure of secret lawlessness

the practices of fanatical cults based on ritual murder . . . ; the exposure

of the world Talmudic plot against Russia, especially plots for the

ritual murder of Gods anointed sovereign and his family; preparation of the Christian world for the war against the coming Antichrist;

and measures to restore a powerful Orthodox Christian tsardom similar to that of Ivan the Terrible [Verkhovskii et al., 1999, p. 105].

Hinduism and Buddhism offer many fewer opportunities for the

rise of fundamentalist movements. This can be explained primarily

by the lack of a rigid system of sacred norms, which does not allow

such norms to be perceived as sociopolitical goals; by the emphasis placed on perfection of the self and the optional interest in

politics; and by the lack of an organized clergy. Political and economic activity in this world has limited significance to Hindus

48 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

and Buddhists. The influence of religion on political life is also

restrained by the pressure of ritual ascriptive networks and of the

caste organization (in Hinduism) as the only or the principal forms

of social bonding2 [Eizenshtadt, 1999, p. 212]. This is why these

types of fundamentalism (and similar variants) are manifested primarily in the form of cultural exclusivity and nationalism. Thus,

during the civil war in Sri Lanka, Buddhism became the banner of

the Singhalese chauvinists in their fight against the Tamil Hindus.

In India, the World Hindu Council, which regards its main goal as

the organization of various Hindu cults for the purpose of uniting the

Hindu community, is energetic; at the beginning of the 1990s it

spun off as its youth wing the extremist group Bajrang Dal (The

Detachment of the Strong), which acts aggressively in regard to

other denominations, as manifested in the reconversion of Indian Christians and Muslims to Hinduism and in the destruction

of churches and mosques [see Glushkova, 2000].

Despite all the differences between individual types of fundamentalism, all fundamentalists share certain common features.

These features include a sense of being the only righteous men

left, adherence to traditional (usually minority) interpretations of

sacred texts and values,3 membership in a special ideological community that relies on a language unique to the initiated (a special

vocabulary that strengthens the identity of the group). Often such

groups set themselves up in opposition to the ruling ethical system

and include members and supporters of peripheral elites. The overwhelming majority of those who join fundamentalist movements are

men (women are co-opted as preservers of the domestic hearth).

The timing of the rise of fundamentalist movements is determined by the pace of modernization in a given country and/or region: hence, in the United States it occurred at the beginning of

the century, in Israel in the period after the establishment of statehood, and in Muslim countries at the end of the 1970s.

* * *

The most influential of these groups in the modern world is Islamic fundamentalism, as the voice of hopes and interests of large

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 49

social groups and strata (here we have in mind legal fundamentalism;

the nature of political extremism is somewhat different). This can be

explained in part by demographic trends: at present there are 1.18

billion Muslims on our planet; their number has grown from 13 percent to 19.5 percent [of the worlds population] in the last hundred

years. The roots of this type of fundamentalism lie in Islamic doctrine itself, in the sacralization of the legal foundations of the relatively egalitarian early Muslim community with its ideal of social

justice. Islam was and still is a faith, but in addition to, outside of,

and often above it there have been political, social-hierarchical,

family and ethnic, and economic trends (mixed with religion and

connected to it by hundreds of ties). In this sense, Islam has been

undergoing a permanent revolution since shortly after Muhammads

deathunder Caliph Osman, who was accused of unjust acts. The

early fundamentalism of the Umayyad decline was connected with

the name of Umar ibn Abd-al Aziz (Caliph Umar II, d. 720), who

initiated government reform in accordance with Islamic principles

and came to be known as the first renewer (mudjaddid) of Islam. It

was also linked to the broad movement of 750, the wave of which

swept the Abbasids into power [Dalv, 1985, pp. 16970 and 195

211]. In fact, the whole history of the medieval Muslim world

abounds with similar examples [see Filshtinskii, 1999].

The fall of the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century (the

destruction of the militaryfeudal system, civil strife, merciless

despotism, corruption, and dissoluteness) led to growing independence in provinces where movements developed against Turkified

Islam. These movements were headed by charismatic leaders

preaching the idea of salvation through purification of the religion

Abd al-Wahha\b in Arabia, [Sidi] Muhammad ibn Ali as-Sanus

in the eastern part of the Sahara Desert, and Muhammad Ahmad

ibn [as-Sayyid] Abd Allah (al-Mahd) in Sudan. All these movements were developing within the parallel contexts of an internal

Islamic dialogue and a confrontation with the West and shared

certain conceptual and practical features:

the view that it was necessary to return to true Islam as a

monotheistic religion (tawhid) and therefore to purify Islam of

50 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

pagan customs and foreign additions. Hence, these groups were

openly hostile to innovations and to vestiges, especially to the

cult of saints, magical rituals, and unions with infidels;

advocacy of independent judgments on theological and legal

issues (ijtihad)that is, the formation of an intellectual tradition

that would make possible the rational interpretation of the general

postulates and polysemantic statements of the Koran and Sunna,

as well as a creative search for answers (in the spirit of Islam) to

the new demands of real life; such a position is incompatible with the

blind worship of the authority (taklid) of any specific theological

or legal school;

the requirement of hijra (resettlement) away from lands controlled by infidels and pagans, which was the first step to declaring a jihad; at that the world was divided into two antagonistic

geographic camps: the domain of unbelief (Dar al-Kufr) and the

domain of Islam (Dar al-Islam); and

the belief in one leader, perceived either as a renewer of

the religionthat is, as an imamor as the expected messiah

(mahdi). Whereas in early Sunni fundamentalism, belief in the

messiah could waver after the defeat or failure of contenders, in

Shiism this idea was limited by citizenship and genealogy: thus,

the tragic death of Caliph Ali Hussains younger son in the Battle

of Karbala (680) was interpreted in the context of a fight between

absolute justice and evil. When the line of the Shiite imams was

cut short, the state acquired a temporal legitimacy in the eyes of

their successors until the rights of the Prophets descendants could

be restored through the return of the bearer of the divine substancethe last, twelfth imam who had disappeared. The traditional Shiite elite has never shared the Sunni viewpoint on electing

caliphs by community agreement; instead, it believes only in absolute agents.

Representatives of the radical wing of Sunni early fundamentalism (the most outstanding among them were ibn Hanbal, ibn

Hazm, ibn Taymyah, and Abd al-Wahhab) created the prototype

of active Islamic political behavior. The following features should

be regarded as the main parameters of this model: militancy and

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 51

jihad in protecting Islam; the combination of the fundamentalist

idea with an active political position; the willingness to challenge

religious and political power and to make sacrifices in the name of

Islam. For their part, the reformers (Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani,

Muhammad Abduh, Abd ar-Rahman al-Kawakibi, and others)

prepared Muslim minds to perceive Islams sociopolitical dynamism and strengthened their faith in its capacity to overcome its

temporary decline and to resist foreign domination.

Thus, the emergence of modern Islamic fundamentalism was

caused by a combination of several historical, ideological, and

cultural factors, although the erosion of traditions and the emergence

of new expectations connected with independence and nationalism served as a catalyst. The key tenets of Sunni fundamentalist

doctrine were developed in the 1950s60s by an Egyptian, Syed

Kutb (19061966), who relied on certain theoretical principles

formulated by a Pakistani, Abul Ala al-Maududi (19031979).

Since the second half of the 1970s a massive penetration of fundamentalist ideas into collective political practice has begun, and the

most important goal of the Islamic ideals adherents has become not

saving Muslims from stagnation, but rather restoring Islam as the

basis of national identity. Below I (briefly) outline the conceptual

field of the classic works on Islamic fundamentalism.

Its ideal is the golden age of Islam embracing the period between Muhammads prophetic mission and the rule of the four

righteous caliphs. In the Mecca period the basic doctrinal principles

monotheism, the power and the sacred nature of Allahwere affirmed, while in the Medina period a set of political, socioeconomic,

military, and spiritual instructions were developed. Over time, different periods arose in the history of the Muslim states, including

some characterized by immoral acts, but responsibility for such

acts is borne not by Islam as a whole but by individual Muslims

who deviated from the path of righteousness [see Kutb, 1981a,

vol. 1, pp. 53344].

Islam plays the role of world beacon because it is the last and most

authentic divine message (Muhammad is the seal of prophets).

Some have argued that the emergence of Islam stripped Judaism

52 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

and Christianity of their meaning, turning them into a collection

of obsolete, and therefore invalid, beliefs and rituals (for example,

the dogma of the Holy Trinity raises doubts concerning the oneness of God), especially since both Judaism and Christianity lack

distinct norms of sociopolitical life [Kutb, 1981a, vol. 2, pp. 924

25]. The age ruled by the white man ended when the white mans

civilization achieved its short-term goals [Kutb, 1993, p. 50].

Since Islamic societies have again fallen into a state of religious ignorance (jahiliyyah),4 and general moral decline robs all

achievements of Western philosophical and scholarly thought of

meaning (that is, ignorance also characterizes modern European

civilization), the goal is proclaimed of restoring Islam within the

framework of a newly organized communitythat of a Muslim

nation [Kutb, 1981b, pp. 58].

The principle of Allahs absolute power (hakimiyyah) is understood to require the restoration of the unified Islamic system, since

the universe is governed by a single law that connects all its parts

in a harmonious and orderly sequence [Kutb, 1980, pp. 8590];

legal and political popular sovereignty is naturally denied.

In the Islamic fundamentalist interpretation, the thesis of the

just government means that an Islamic state should rely not on

popular sovereignty by rather on sacred lawSharia (the theological democracy of al-Maududi and Kutbs system of mutual

consultations). Developing his model of an ideal Islamic state,

al-Maududi accepted the principle of universal suffrage as the foundation for introducing modern political procedures. At the same

time, according to al-Maududi, executive power can be given only

to a male leader (emir) who must do as Allah orders. A council

helps him implement his governing functions and is elected by

adult men and women who have already accepted the fundamentals of the Constitution. Since an Islamic state is primarily an

ideological unity, only those who are faithful to its doctrinal principles are considered to be first-class citizens. The rest of the population, as long as they stay loyal and obedient, are given certain

rights as second-class citizens [Maududi, 1983, pp. 1665].

Economic justice proceeds from the assumption that the com-

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 53

munity (and undoubtedly Allah as well) owns all material and financial resources. The community members simply make use of

these resources in line with their labor contribution. Although private property earned through individual labor, profit, and free competition are recognized as essential features of the Islamic economic

system, they are regulated according to what serves the well-being of the community as a whole. Monopolies and usury are banned,

while the zakat (a tax in favor of needy Muslims), combined with

government policy, is designed to prevent acute social stratification.

Moral perfection is one key to overcoming the state of ignorance. The lives of the Prophet and his close followers must be a

moral beacon for believers. A major part of Islamic upbringing

depends on the family. which acts as a micro-model of society.

Kutb emphasizes that Islam pays more attention to the family than

to other institutions: the whole Islamic social system is an extended

family system linked to the sacred order and established in accordance with human instincts and needs. Kutb is also trying to provide rational grounds for the division of labor between men and

women based on their physical, intellectual, and emotional traits

(a woman is to function as wife and mother, and a man as indisputable authority, guarantor of material welfare, and active participant in political life; they enter the marriage voluntarily as equal

partners) [Kutb, 1981a, vol. 1, pp. 23441].

The cause of Islam requires the creation of an elite vanguard

usba mumina (the union of believers)which is capable of revealing the true doctrinal essence and of destroying modern-day

idols. Since Muslims occupy first place when it comes to mastering Islamic doctrine and methods, they can accomplish that

honorable task better than anybody else. At the same time, they

can give others what they need and restore their own identity in

the process [Kutb, 1981b, pp. 813].

Jihad is understood as neither a holy war to convert infidels nor

an instrument of self-defense used by a community of believers. A

declaration of jihad implies that an individual has joined a new

community (the world of faith), which rejects all laws of the world

outside that faith. It also indicates a revolutionary struggle for the

54 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

revival of Islam, including a wide range of actions: from articles

in the mass media and charitable donations to the use of force

[Kutb, 1981a, vol. 4, p. 21012].

Fundamentalist Sunni Islam was developed by Hassan al-Turabi

in Sudan, Issam al-Attar in Syria, Abbasi al-Madani in Algeria,

Rashid al-Gannushi in Tunisia, Erbakan in Turkey, Mustafa asSibai in Egypt, and others. Some of them were familiar with Marxism and Western philosophy in addition to Islam. For example,

al-Gannushi called attention to the necessity of creating (under

President [Habib] Bourguibas one-party regime in Tunisia) mass

mobilization centers in mosques, of fighting for the rights of workers and women, and of eliminating contradictions between secular

law and the Sharia. He understood jihad as nonviolent sociopolitical

activities [see Gannushi, 1984]. As-Sibai supported Islamic socialism; he advocated the natural rights of each Muslim and

defended the right to property based on zakat and irs (the Islamic

right to inherit) and nationalization [see Bagdadi, 1998]. Muammar

al-Qaddafi incorporated many fundamentalist elements in his Green

Book.

The special characteristics of Shiite fundamentalism can be

explained by the Shiite religious system (the doctrine of a secret

imam, unconditional predetermination, etc.) and by its clerical

organization, which is more expressive and more independent of

government power than the Sunni clergy (the social-corporative

class of the ulema) [see Doroshenko, 1998]. The Iraqi ayatollah

and theoretician Muhammad Bakir al-Sadr defined the Islamic

system as an organic combination of the earthly and heavenly

worlds, attainable if the ideal sociopolitical organization revealed

to humanity by Allah can be realized. It is superior to other systems because it ensures spirituality and morality, takes into account the interests of both individuals and society, and supports a

balance between them through conformity to the moral criterion

(service to Allah). The Iraqi scholar singled out two key functions

of an Islamic state: to bring up each individual in accordance with the

Islamic ideological principle; and to monitor various outside tendencies, allowing no deviations [al-Sadr, 1989, pp. 2934].

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 55

Al-Sadr also developed a draft constitution for an Islamic republic in which he defended the principle of marjiyyah [the supreme religious authorityEd.].5 Interpreting the righteous

marjiyyah as a legal (juridical) expression of Islam, al-Sadr believes that the supreme religious leader is a deputy or representative of the secret imam and therefore should be the head of the

government and the commander in chief, with the right to determine the legality of constitutional provisions from the standpoint

of Sharia, to decide whether laws passed by the nationally elected

legislative assembly are constitutional, to approve candidates for

the position of head of the executive branch, and to appoint the

supreme court, the appeals council, and the council of a hundred

theologians, mullahs, and religious intellectuals that would implement supreme guidance.

The interpretation of marjiyyah as a covenant between Allah

and the imams implies that the man elected to that position must

be a model leaderrighteous, devoted to the idea of an Islamic

state, and capable of governing and interpreting Islam [al-Sadr,

1978, pp. 1835]. In fact, [Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah]

Khomeinis doctrine is a development of this principle and a theoretical substantiation of what is called vilaiyat al-fakikh in Arabic

(in Farsi it is velaiyat-e fakikh) [transliterated from CyrillicEd.]

that is, guidelines of a legal specialist. According to Khomeini,

the Koran and Sunna contain all the laws and directives a man

needs to achieve happiness and to perfect his state, and experts in

Sharia can best implement these laws and directives [see Khomeini,

1993]. In essence, the recognition that political leadership is exclusively the business of the clergy means a break with the Shiite

theological tradition.

* * *

In my opinion, the most important task is to separate what the

fundamentalists have achieved or are trying to achieve from what

their theoretical and practical activities mean for the rest of the

world. As a rule, more attention is paid to the former question. The

56 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

essence of the latter can be formulated as follows: are autonomous

religious values compatible with the modern construction of the

material world?

From the moment a nation emerges in the political arena, politics becomes a characteristic and unifying activity of its citizens

(even if it also juxtaposes them based on their group affiliation).

From then on, they are united by a collective goal, which implies

movement beyond their former frame of existence and transition

to a community. Here we can discern an analogy with religion,

which in the etymological sense is unifying. Affiliation with a religion and affiliation with a political trend are alike in one respect:

self-determination always rests not on scientific criteria but on

faith. In the case of religion, this is because religion is a revelation; where the choice involves a political position, the choice involves faith because whatever rational motives lie behind it, ideally

it requires taking into account an endless multiplicity of factors. A

political choice involves choosing a hypothesis, especially since

politics is oriented toward the future and requires the engagement

of an individuals entire personalitymind and emotions. Even

when views are progressive, many people express their convictions in an irrational way (suffice it to recall the key words of the

French Revolutionliberty, equality, and fraternity). Also, the first

type of modern ideology was, according to Karl Mannheim, the

orgiastic community of the Anabaptists. So maybe the religious

revival of the twentieth century has a powerful secular component, or maybe it is covering up a secular movement with religious discourse and rituals and forms of collective behavior.

As I have tried to show, fundamentalism is not simply a support

of any existing tradition. It is an ideological construct and a political platform consciously opposed to certain contemporary development processes. It is both a product of modernization and a

reaction to the ever-growing significance of criteria that are neither religious nor spiritual. Its theoreticians sift tradition through

the sieve of authenticity based on their views of the ideal and substantiate their position with direct use of a sacred text (it is no

accident that S. Kutbs main work is a six-volume commentary on

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 57

the Koran). In so doing, they set up an arbitrary hierarchy governing the religions aspects or symbols and introducing innovations

(for example, theological democracy and the guidelines of a

legal specialist).

Thus, the antimodern charge of fundamentalism is characterized by quite modern features. These include a strong predisposition to develop not only a distinct individual worldview but also a

totalitarian ideology with elements of rationality, a conviction of

the primacy of politics in which the transformation of central political institutions is regarded as a supreme goal, and a readiness to

use the technological and organizational achievements of civilization. This, above all, differentiates modern religious fundamentalism from its predecessors. Fundamentalism overcomes the

contradiction between religion and ideology by combining revelation (faith) with sense and expediency (reason).

Of course, talk about the secular nature of spiritual matters does

not apply to Islamic fundamentalism (the most influential fundamentalist ideological trend and movement). Within this type of

fundamentalism, the ability to receive divine inspiration and guidance is not destroyed, nor does it have a cultural and political program promoting liberation from theological thinking. Its adherents

think that liberation from Sharia or from the Sharia mentality is

not possible for a Muslim and that an Islamic state and society can

emerge only when the sacred law is followed absolutely. But are

the state and the ideas of statehood diminished in countries where

fundamentalism is especially successful (that is, in countries where

it leaves the opposition and joins the active polity)? I try to show

that they are not.

The age of the great empires (Ottoman, Safavid, Mongol) was

extended in the Islamic world from the sixteenth to the beginning

of the twentieth centuries. During that period problems involving

the coexistence of various trends and political loyalty within Islam were solved in different ways depending on the specific political situation. When a nation-state was formed, the new

interpretation of Islam came to be perceived as a lack of political

loyalty, while official Islam was turned into a powerful means to

58 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

defend the nation-state. Sunni fundamentalists responded to this

by accusing both the ruling elite and the official clergy of corruption. The Shiite forces opposed to the shah declared that he did not

guarantee the right of the clergy to represent Islam and had therefore lost his legitimacy. In both cases, the borrowing of religious

resources strengthened opposition to the government. The paradox is that the fundamentalists themselves could succeed only by

using the modern government apparatus to achieve their goals.

The Shiite mullahs who came to power in Iran in 1979 were fundamentalists and modernists at the same time. The example of

Iran, as an indirect manifestation of fundamentalist consciousness

in political discourse, shows its capacity for theoretical reflection,

development, and mastery of new types of political interaction at

the national and world levels. Economic and financial changes

naturally play a certain role here, as does mastery of modern communications and technologies (for example, the nuclear project in

Bushehr), which change behavior by supplying new motivations.

In this respect, the position of Irans president, Muhammad

Khatami, whose legitimacy relies not only on religious authority

but also on his popular election (he received over 80 percent of the

votes during the 2001 elections), is of particular interest. Khatami

advocates a constructive dialogue, without turning the only

Procrustean model of freedom in the modern world into an absolute, in support of the multipolar world (all people have the right

to participate in activities that will shape the world of the third

millennium) and in support of greater openness in Islamic society

(Islam has never considered the policy of isolationism to be sensible and has always been ready to encounter opposing views).

By the way, the dialogue among civilizations is an old slogan

from the shahs white revolution, but as expressed by Irans current president it undoubtedly acquires a reformist ring. Stating that

all civilizations are transient, Khatami speaks of the need to develop theology and reach a different level of understanding in order to meet the demands of the revolution and solve the practical

tasks of the day. He also recognizes that legal activity by the opposition is legitimate; that is, his idea of dialogue implies not only an

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 59

extended dialoguewith the world at largebut also an internal

dialoguewithin Iranian society [Khatami, 2001, pp. 64, 117, 121

24, 128]. A new Islamic civilization cannot be built without creating an Islamic civil society in every Muslim country, and this

should include the positive achievements of Western civil society.

While the genotype of the latter is polis, the former goes back to

Medina in the Prophets lifetime, to the beginning of life in accordance with Allahs time. In such a society dictatorship, even

that of the majority, is not possible, and human rights are respected;

its members are entitled to determine their own fate, to control the

governance of the country and to hold the government accountable. These rights should be enjoyed by non-Muslims as well. This

view envisages the functioning of various parties and groups and

the development of civil institutionsnaturally, within the framework of the accepted religious system [Khatami, 2001, pp. 34

37]. In January 2001, 103 political parties and groups were

registered in Iran, about 10 of which had a tangible political presence; in essence, these are factions and groups within the familiar

conservativereformer dichotomy [Vagin, 2001, pp. 10910].

In the 1990s fundamentalists held power in Sudan as well (which

made al-Turabi reconsider some of his views in order to strengthen

the unity and stability of the state). In addition, they also participate (at different levels) in the political systems of Yemen and

Lebanon. Meanwhile, the Taliban, which controlled 90 percent of

Afghanistan, can be characterized (in contrast to Gulbuddin

Hekmatiars fundamentalist mujaheddin) as a traditionalist movement advocating patriarchal norms of social organization and behavior but having vague political views, including on how to govern

[see Umnov, 2001]. In Israel the probability of the Gush Emunim

blocs further rise depends on its readiness to compromise with

the government-oriented ideology of the major political parties.

In this way, by organizing themselves and by organizing others in

power, not only do fundamentalist movements acquire a strong

political weapon to restructure the world, but they also become

integrated into the very system they oppose.

The fundamentalist idea plays an ambivalent role. Especially in

60 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

its radical form, this idea contains both constructive and destructive aspects. Fundamentalists often do not distinguish between the

personal and the social, between the individual and the community, and between the rational and the irrational, but they can contrast these elements in such a way that the individual and the private

do not disappear completely, so that politics preserves a certain

autonomy with regard to the religious sphere (or the religious sphere

with regard to the political one). They often control the nature of

the discourse or activity in the public sphere, and in the process

they can develop reformist tendencies or even modernize (which,

as noted above, usually happens in response to a new national area

of responsibility). The results of implementing what at first seemed

to be utopian projects significantly differ from the ideal. Moreover, the greater a projects scope and the longer its practical life,

the more obvious are such deviations; if a project survives, it is

capable of evolution. Therefore, it is legitimate to regard legal fundamentalism as one element in national development.

The fundamentalist model is more than a utopia, because it objectively influences the search for a rational path of development

and the creation of normative models for humanitys future. It is

possible to realize the scale of this function of fundamentalist

models only within the framework of a different worldview, in

which the world is perceived not as a multitude of objects and

contradictions between them but rather as an integral system. To

interpret various political spaces and traditional and transient societies correctly, one clearly needs a broader application of categories of political consciousness and political culture and an

introduction into political analysis of concepts of justice and equality, which, according to Immanuel Wallerstein, determine the vector of human development. Talking about the existence of the next

world does not mean only that in addition to earthly life there is

another world as well. It means to evaluate life by applying not

only everyday criteria (status or wealth) but also the criteria of

eternal life. The fundamentalist idea is also, however, no less important as a utopia. It gives life a different existential meaning and

helps us understand the interests and problems of the type of mind

RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW 61

it represents while linking it to a different chronotope.

Pure, abstract fundamentalism is unlikely to win a political victory in the long term: either it will be replaced or it will change.

But fundamentalism can succeed even if it is defeated in the political sphere. In the postindustrial area it is capable of challenging modernism on the basis of its spiritual mandate, which reflects

the tendency to revive an authentic moral and cultural legacy and

without which it is not possible to move forward. If one is to make

a contribution to a new vision of the world, it is probably necessary to find oneself first.

Notes

1. Considering all other cults (even monotheistic ones) satanic, Lefebvre

predicted the death of Catholicism if Islam triumphed and preached the renewal

of empire and colonization.

2. This circumstance gave rise to attempts to use Hinduism as an ideological

component of national development.

3. Thus, in Iran, even after the Islamists came to power, they still perceived

themselves as a minority with regard to the sinful world.

4. By the way, Kutbs follower and brother Muhammad interpreted that concept in a particular moral and intellectual sense, interpreting it as a psychological state of denying Allahs guidance [Kutb, 1964, p. 11].

5. The term is derived from marja at-taklida source of emulation (the

highest rank of Shiite mujaheddin).

References

Aizenshtadt, S. 1994. Fundamentalizm: fenomenologicheskie nabliudeniia i

sravnitelnye kharakteristiki. Chelovek, no. 6.

Bagdadi, A.M. 1998. Problemy islamskogo fundamentalizma v Egipte. Moscow:

dissertation presented for the degree of Candidate of Political Science.

Cerillo, A., Jr., and Dempster, M.W. 1989. Salt and Light: Evangelical Political

Thought in Modern America. Washington.

Dalv, Burgan ad-Din. 1985. Mashakhid fi iadat kitaba at-tarikh al-arabii alislamii (A new view of Arab-Islamic history: sketches). Beirut. [All Arabic

titles transliterated from Cyrillic.Ed.]

Doroshenko, E.A. 1998. Shiitskoe dukhovenstvo v dvukh revoliutsiiakh: 1905

1911 i 19781979 gg. Moscow.

Eizenshtadt, Sh. 1999. Revoliutsiia i preobrazovaniie obshchestv. Moscow.

Filshtinskii, I.M. 1999. Istoriia arabov i Khalifata (7501517 gg). Moscow.

Gannushi, R. 1984. Makaliat (Articles). Paris.

62 RUSSIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW

Glushkova, I. 2000. Pochemu v Indii ubivaiut khristian? NGreligii, no. 23.

Haynes, J., ed. 1995. Religion, Fundamentalism, and Ethnicity: A Global

Prospective. Geneva.

Kamu [Camus], J.-I. 1990. Antiprogressizm i antiekumenizm: katolicheskii

integrizm. In Vozvrashchenie religioznogo faktora v politiku. Moscow.

Khatami, M. 2001. Islam, dialog i grazhdanskoe obshchestvo. Moscow.

Khomeini, R.M. 1993. Islamskoe pravlenie. Almaty.

Kutb, M. 1964. Jakhilia al-karn al-ashrin (Ignorance of the twentieth century).

Cairo.

Kutb, S. 1980. Khasais at-tasavvur al-islamii (Unique features of Islam). Beirut.

. 1981a. Fi zilal al-Quran (Under the protection of the Koran). 6 vols.

Beirut.

. 1981b. Maalim fi at-tarik (Milestones on the path). Beirut.

. 1993. Budushchee prinadlezhit islamu. Moscow.

Malashenko, A.V. 1997. Nepriiatie fundamentalizma kak ego zerkalnoe

otrazhenie. NGreligii, no. 12.

Maududi, S.A.A. 1983. First Principles of the Islamic State. Lahore.

Miloslavskii, G.V. 1999. Preface. In Volkov, A.B. Religioznyi fundamentalizm

v Izraile i Palestinskaia problema. Moscow.

Ar-Raid. 1964. Moajam liugavii asrii (Dictionary of modern Arabic). Beirut.

Al-Sadr, M.B. 1978. Liamkha fikriia tamkhidia an mashroa dustur al-Jumkhuria

al-islamia fi Iran (A preliminary glance at the Islamic Republics Constitution

in Iran). Tehran.

. 1989. Our Philosophy. Shafagh.

Sagadeev, A.V. 1987. Filosofskoe nasledie musulmanskogo mira i sovremennaia

ideologicheskaia borba. Moscow.

. 1993. Islamskii fundamentalizm: zhiznennyi fakt ili propagandistskaia

fiktsiia? Rossiia i musulmanskii mir, no. 10.

Tuvinov, A. 2001. Mnogolikii fundamentalizm. NGreligii, no. 18.

Umnov, A. 2001. Taliban v islamskom kontekste. In Islam na postsovetskom

prostranstve: vzgliad iznutri. Moscow.

Vagin, M.V. 2001. Prezident M. Khatami i ego kontseptsii Islamskogo

grazhdanskogo obshchestva i dialoga tsivilizatsii. In Iran: Islam i vlast.

Moscow.

Verkhovskii, A., Mikhailovskaia, E., and Pribylovskii, V. 1999. Politicheskaia

ksenofobiia: radikalnye gruppy. Predstavleniia liderov. Rol tserkvi. Moscow.

Volkov, A.B. 1999. Religioznyi fundamentalizm v Izraile i Palestinskaia problema.

Moscow.

Selected by Nils Wessell

Translated by Larisa Galperin

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HSE Induction Training 1687407986Document59 pagesHSE Induction Training 1687407986vishnuvarthanNo ratings yet

- COSL Brochure 2023Document18 pagesCOSL Brochure 2023DaniloNo ratings yet

- TG - Health 3 - Q3Document29 pagesTG - Health 3 - Q3LouieNo ratings yet

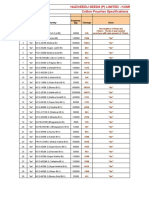

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDocument2 pagesCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytNo ratings yet

- IsaiahDocument7 pagesIsaiahJett Rovee Navarro100% (1)

- ESS Revision Session 2 - Topics 5-8 & P1 - 2Document54 pagesESS Revision Session 2 - Topics 5-8 & P1 - 2jinLNo ratings yet

- Coerver Sample Session Age 10 Age 12Document5 pagesCoerver Sample Session Age 10 Age 12Moreno LuponiNo ratings yet

- Accountancy Service Requirements of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesAccountancy Service Requirements of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in The PhilippinesJEROME ORILLOSANo ratings yet

- Things in The Classroom WorksheetDocument2 pagesThings in The Classroom WorksheetElizabeth AstaizaNo ratings yet

- Tateni Home Care ServicesDocument2 pagesTateni Home Care ServicesAlejandro CardonaNo ratings yet

- PDF - Unpacking LRC and LIC Calculations For PC InsurersDocument14 pagesPDF - Unpacking LRC and LIC Calculations For PC Insurersnod32_1206No ratings yet

- God's Word in Holy Citadel New Jerusalem" Monastery, Glodeni - Romania, Redactor Note. Translated by I.ADocument6 pagesGod's Word in Holy Citadel New Jerusalem" Monastery, Glodeni - Romania, Redactor Note. Translated by I.Abillydean_enNo ratings yet

- Industrial Cpmplus Enterprise Connectivity Collaborative Production ManagementDocument8 pagesIndustrial Cpmplus Enterprise Connectivity Collaborative Production ManagementEng Ahmad Bk AlbakheetNo ratings yet

- Dialogue About Handling ComplaintDocument3 pagesDialogue About Handling ComplaintKarimah Rameli100% (4)

- Referensi PUR - Urethane Surface coating-BlockedISO (Baxenden) - 20160802 PDFDocument6 pagesReferensi PUR - Urethane Surface coating-BlockedISO (Baxenden) - 20160802 PDFFahmi Januar AnugrahNo ratings yet

- 1 3 Quest-Answer 2014Document8 pages1 3 Quest-Answer 2014api-246595728No ratings yet

- Peer-to-Peer Lending Using BlockchainDocument22 pagesPeer-to-Peer Lending Using BlockchainLuis QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Grammar: English - Form 3Document39 pagesGrammar: English - Form 3bellbeh1988No ratings yet

- TCS Digital - Quantitative AptitudeDocument39 pagesTCS Digital - Quantitative AptitudeManimegalaiNo ratings yet

- Determination of Physicochemical Pollutants in Wastewater and Some Food Crops Grown Along Kakuri Brewery Wastewater Channels, Kaduna State, NigeriaDocument5 pagesDetermination of Physicochemical Pollutants in Wastewater and Some Food Crops Grown Along Kakuri Brewery Wastewater Channels, Kaduna State, NigeriamiguelNo ratings yet

- Comparing ODS RTF in Batch Using VBA and SASDocument8 pagesComparing ODS RTF in Batch Using VBA and SASseafish1976No ratings yet

- Quizo Yupanqui StoryDocument8 pagesQuizo Yupanqui StoryrickfrombrooklynNo ratings yet

- The Rescue Agreement 1968 (Udara Angkasa)Document12 pagesThe Rescue Agreement 1968 (Udara Angkasa)Rika Masirilla Septiari SoedarmoNo ratings yet

- Atlantean Dolphins PDFDocument40 pagesAtlantean Dolphins PDFBethany DayNo ratings yet

- Bike Chasis DesignDocument7 pagesBike Chasis Designparth sarthyNo ratings yet

- Research On Goat Nutrition and Management in Mediterranean Middle East and Adjacent Arab Countries IDocument20 pagesResearch On Goat Nutrition and Management in Mediterranean Middle East and Adjacent Arab Countries IDebraj DattaNo ratings yet

- Judges Kings ProphetsDocument60 pagesJudges Kings ProphetsKim John BolardeNo ratings yet

- Install GuideDocument64 pagesInstall GuideJorge Luis Yaya Cruzado67% (3)

- Budget ProposalDocument1 pageBudget ProposalXean miNo ratings yet

- Mutants & Masterminds 3e - Power Profile - Death PowersDocument6 pagesMutants & Masterminds 3e - Power Profile - Death PowersMichael MorganNo ratings yet