Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Centenary of Karl Jaspers 'S General Psychopathology: Implications For Molecular Psychiatry

Uploaded by

JohnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Centenary of Karl Jaspers 'S General Psychopathology: Implications For Molecular Psychiatry

Uploaded by

JohnCopyright:

Available Formats

Thome Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 2:3

http://www.jmolecularpsychiatry.com/content/2/1/3

REVIEW

JMP

Open Access

Centenary of Karl Jasperss general

psychopathology: implications for molecular

psychiatry

Johannes Thome

Abstract

Modern molecular psychiatry benefits immensely from the scientific and technological advances of general

neuroscience (including genetics, epigenetics, and proteomics). This progress of molecular psychiatry, however,

will be to a degree unbalanced and epiphytic should the development of the corresponding theoretical

frameworks and conceptualization tools that allow contextualization of the individual neuroscientific findings within

the specific perspective of mental health care issues be neglected. The General Psychopathology, published by Karl

Jaspers in 1913, is considered a groundbreaking work in psychiatric literature, having established psychopathology

as a space of critical methodological self-reflection, and delineating a scientific methodology specific to psychiatry.

With the advance of neurobiology and molecular neuroscience and its adoption in psychiatric research, however, a

growing alienation between current research-oriented neuropsychiatry and the classical psychopathological

literature is evident. Further, consensus-based international classification criteria, although useful for providing an

internationally accepted system of reliable psychiatric diagnostic categories, further contribute to a neglect of genuinely

autonomous thought on psychopathology. Nevertheless, many of the unsolved theoretical problems of psychiatry,

including those in the areas of nosology, anthropology, ethics, epistemology and methodology, might be fruitfully

addressed by a re-examination of classic texts, such as Jasperss General Psychopathology, and their further development

and adaptation for 21st century psychiatry.

Keywords: Brain, Methodology, Mind, Neuroscience, Philosophy, Materialism, Reductionism, Theory of science

Review

Introduction

The young Karl Jaspers (30 years of age) published the

first edition of his General Psychopathology at a time

when psychiatry had only recently been solidly established as a medical and scientific discipline, and ambitious research projects, such as that of Kraepelin, were

inaugurated in order to uncover the fundamental bases

of psychiatric conditions. The enthusiasm for purely

biological approaches in psychiatry according to

Griesingers dictum that all psychiatric disorders were

brain disorders, however, was already meeting with increasing skepticism; Freud, for example, who had commenced his career as a neuropathologist, had already

decided to proceed within a totally different theoretical

Correspondence: Johannes.thome@med.uni-rostock.de

Department of Psychiatry, University of Rostock, Gehlsheimerstrae 20, 18147

Rostock, Germany

framework, a psychological approach he termed psychoanalysis. Jaspers seemed to strongly feel the need to critically evaluate psychiatric methodology, and to develop a

methodological system that would be based on dynamic

principles, permitting continuous re-adjustment as the

discipline of psychiatry generated increasing knowledge

about the mind and the brain [1].

In parallel with these genuine scientific-philosophical

considerations, Jaspers also composed his work in order

to foster his academic career. It was submitted to the

University of Heidelberg as his habilitation thesis, in

order to obtain his license to teach psychology at the

university; it also enabled him to move from the Medical

Faculty to the Faculty of Philosophy. This practical aspect shares some similarities with the preparation of the

Tractatus logico-philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein,

who similarly employed his labors to the advantage not

only of philosophy, but also in order to earn his doctoral

2014 Thome; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Thome Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 2:3

http://www.jmolecularpsychiatry.com/content/2/1/3

degree from Cambridge University. An acquaintance

with the biography of Karl Jaspers will greatly enhance

the ability to analyze and comprehend his work and to

place it in its historical context.

Karl Jaspers: biography

Born in 1883 in Oldenburg (Germany), Karl Jaspers suffered poor health throughout his youth (hereditary

bronchiectasis) which, according to his own testimony,

shaped his character to a certain extent, as it rendered

him physically fragile and thus required stringent discipline in order to overcome his weakness. Born into an

upper middle-class family, he was able to study law for a

few semesters in Heidelberg and Munich before beginning

his medical training during 1902 in Berlin, Gttingen and

Heidelberg. In 1908, he obtained his medical degree,

and worked until 1914 as a junior physician with Franz

Nissl, who was at this time Director of the University

Psychiatric Hospital in Heidelberg [2]. With the publication of the General Psychopathology he began a career

as philosopher, and never returned to practicing medicine or psychiatry. Instead, he became, together with

Martin Heidegger, one of the most important representatives of German existentialism [3]. Unlike Heidegger,

however, he opposed National Socialism from the outset; further, he refused to divorce his Jewish wife, as a result of which the couple lived in constant threat. Jaspers

was forced by the regime into premature retirement from

the university in 1937; a year later he was also barred from

publishing.

From 1945 to 1948, he actively supported the reestablishment of free academic life at Heidelberg University and other academic centers. He was disappointed by

political developments in post-war Germany, however,

and emigrated to Switzerland in 1948, where he obtained

a professorship in philosophy at Basle University. He

adopted Swiss citizenship, and died in Basle in 1969.

The book

The General Pathology has appeared in no less than

eight editions since its first publication in 1913 [4] to

the latest edition immediately before its authors death.

Jaspers contributed a significant amount of fresh material to each new edition, with the consequence that the

eighth edition (1965) was significantly more voluminous

than the first. Later editions also contain interesting

comments by Jaspers regarding the reception and misperceptions of his work. Successive editions naturally

differ considerably from the first, so that detailed analysis also needs to reflect the metamorphosis of this

work over time. The fourth edition, in particular, represents a fundamental revision of the earlier publications

[3]. This paper will be based on the fifth edition of 1948

[5], together with consideration of the first in order to

Page 2 of 5

clearly distinguish between the original work and later

additions.

While the General Psychopathology is generally considered one of the major works in psychiatric literature,

it is interesting to notice that very few papers published

over the past 20 years in Medline-listed psychiatric,

medical and scientific journals have concerned themselves with his thought (03 articles per year). In the

centenary year of 2013, on the other hand, around 25 articles can be retrieved if one searches for titles including

Jaspers and psychopathology. This is clearly an indication that Jaspers work is remembered for historical

reasons, but seems to play only a minor role in current

scientific discourse in psychiatry. With the advance of

molecular psychiatry, the reception and reflection of

Jasperss psychopathology seems to be receding ever

further.

Molecular psychiatry

While the so-called biological psychiatry of the 1970s,

1980s and 1990s was mostly based upon quite reductionist (and retrospectively simplistic) hypotheses about

psychiatric conditions (such as simple neurotransmitter

hypotheses developed in analogy to models of neurological disorders, such as Parkinsons disease), the introduction of more advanced molecular neuroscience

methods [6,7] makes it possible to apply hypothesisgenerating approaches in modern molecular psychiatry,

and also to integrate genetic aspects into environmental

models (including social and psychological aspects)

of psychiatric conditions [8]. Blinkered reductionist

thought has given way to a much broader approach that

allows space for questions about philosophical aspects

of psychiatry, including its methodology, anthropology,

and ethics [9]. From a therapeutic perspective, the focus

is no longer purely on biological (for example, pharmacological) or psychotherapeutic approaches, but on an

integration of both, with the goal of a unique and individualized therapy for each patient. Most practicing

psychiatrists would probably describe themselves as

non-reductionist materialists who are not only willing

but keen to critically reflect upon their actions in clinical practice and research. However, this discourse requires a non-biological terminology and methodology

that could at least partially be provided by Jasperss

General Psychopathology.

Differences between the philosophical/

psychopathological approach and modern psychiatry/

neuroscience

Integrating psychopathological thinking into modern

molecular psychiatry might at least initially be difficult

due to a number of significant differences. Formally, discoveries in molecular psychiatry are published in relatively

Thome Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 2:3

http://www.jmolecularpsychiatry.com/content/2/1/3

short journal articles with a very short half-life of sometimes only a few months. In contrast, psychopathological

thinking is similar to philosophical thought outlined

in rather voluminous books whose content can remain

relevant for more than a hundred years (such as Jaspers).

Further, classic psychopathological work is not always

published in the current lingua franca (English), and translations of appropriate quality are not always available,

complicating the reception of such work.

Methodologically, the philosophical method of developing ideas and arguments based upon logic, conjectures and

refutations, as applied to psychopathology, is quite different

from the empirical-experimental approach employed in

molecular psychiatry [10]. A tendency towards reductionism (required in order to establish experimental settings) in

the latter contrasts with an attempt by the former to understand the big picture in its entirety.

There nevertheless exists a common basis for trying to

better understand the mind and brain, and to fundamentally comprehend practical psychiatry. In this context,

Jaspers often used the word elucidation (Erhellung), a

term often found in modern scientific texts.

Psychopathology as methodology

Jaspers underscored the contrast between an individual patient with their personal history, and the experience of complex states or conditions that are independent of individuals.

He postulated that the expression (Ausdruck) and facts

(Tatbestnde) of this condition need to be differentiated,

and that these terms must not be confused with the mental

(das Psychische), which cannot be investigated per se.

He also discussed the relation between general psychopathology and somatic medicine, and spoke of a deep unity

(innige Einheit) between the mind/psyche and the physical/

somatic. Nonetheless, a 1:1 correspondence between the

two is not possible, despite certain parallelisms and interdependencies. It rather is like a continent observed from

two sides, an ocean whose coastline is examined. He

therefore postulated that general psychopathology should

be freed from the slavery (Knechtschaft) imposed by the

dogma that psychiatric disorders are brain disorders.

Nevertheless, psychopathology is, according to Jaspers,

intimately related to medicine and psychology. If the potential of psychopathology is denied, and progress identified only with histology and serology, then there exists

a confusion between the progress represented by discoveries of physical phenomena and the autonomous progress of psychopathology, which for Jaspers is defined by

its methodology.

Terminology

Jaspers attempted to derive a specific psychopathological

terminology by discussing three central problem areas:

comparison of human beings and animals in order to

Page 3 of 5

define their similarities and dissimilarities; objectification

(and organization) of the soul; and the interaction between

the inner and outer worlds of the individual. The first area

provided a useful somatic terminology because of identified somatic similarities. The dissimilarities lead to terms

such as personhood (Menschsein), mind (Geist), and

human soul (Menschenseele), and also give rise to the

question whether animals can suffer from mental illnesses,

which would be necessary, were animal models in psychiatry to be valid; this remains a highly contested question

in current empirical molecular-psychiatric research. It also

reminds one of Tim Crows dictum that schizophrenia is

the price that homo sapiens pays for language [11], and

other unique features of being human.

Jaspers also stressed that the soul per se is not the direct

object of the psychopathological project. The soul becomes rather indirectly an object via phenomena that can

be perceived, that is, via matters of fact (Tatbestnde), including somatic (organic) data. The soul/mind itself remains the all-encompassing that cannot be objectified

itself. This train of thought on the soul/mind (Seele) provided key psychopathological terms, such as consciousness

(inwardness of experience: Innerlichkeit der Erfahrung),

representational consciousness (objektives Bewusstsein),

self reflection (Selbstreflexion), existence in one's world

(Sein in ihrer Welt), as well as becoming (Werden), development (Entfaltung), and differentiation (Differenzierung),

terms which also signify its non-finality (nicht engltig)

and incompletion (nicht vollendet).

Finally, the interaction between the inner world

(Innenwelt) and the environment (Umwelt) makes it

necessary to interpret life from a psychopathological view

as existence in its world (das Leben als Dasein in seiner

Welt), which again unlocks a thesaurus of terms that have,

in part, become part of current molecular psychiatry (geneenvironment interaction, stimulus-reaction, ego-subject

matter, subject-object, predisposition-milieu).

Prejudices

Jaspers listed several prejudices with which psychopathology can be confronted and which need clarification:

The philosophical prejudice or misconception assumes

that psychopathology employs merely deductive methods;

that is, it derives conclusions from a hermetic set of preconceived theoretical ideas, whereas psychopathology, in

fact, is based upon a pro-science (pro-empirical) outlook.

So-called neurophilosophy had, however, not yet been

developed at the time when Jaspers was writing; this

form of empirical philosophy aims at unifying theories

of the mind and the brain [12] according to a radically scientific and neurobiological approach which assumes that

even philosophy can be replaced by neuroscience, a view

that has often been criticized as being overly nave and

reductionist.

Thome Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 2:3

http://www.jmolecularpsychiatry.com/content/2/1/3

The theoretical prejudice sees psychopathology as a

unifying theory, but Jaspers actually argued that the mental world (Seelenleben) cannot be reduced (zurckgefhrt

werden) to a few universal principles. It would therefore be

wrong to metaphorically compare the soul/mind to an

ocean, with psychopathology discovering and describing

more and more of its shores and islands.

The somatic prejudice identifies psychopathology with

physiological, anatomical and/or general biological phenomena and processes. In this context, Jaspers states that

identifying the methodology underlying Meynerts and

Wernickes work on aphasias and apraxias with genuine

psychopathological practice would lead to brain mythology (Hirnmythologie) [13]. Nevertheless, Jaspers underscored repeatedly the fact that the psychological and the

somatic (das Seelische und das Krperliche) are intertwined

through parallelisms and interactions (Wechselwirkungen).

The psychological-intellectualistic prejudice implies an

interpretation of psychopathology that considers it as

pure speculation without any basis in reality. Such a

stance, however, has rendered it impossible for so-called

somaticists to accept phenomena such as hysteria.

The image prejudice is defined by a reduction of psychopathological phenomena to pure images (such as

spatial images) that are misinterpreted as the actual design of the soul/mind (Bilder als Seelengrundrisse).

The medical prejudice, finally, challenges any psychopathological conceptualization by postulating that any

such project must be based solely upon quantifiable phenomena. By pointing out that psychopathology must go

beyond purely measurable parameters, Jaspers has anticipated the raise of so-called qualitative research methods,

which are today attracting increasing attention, and largely

derive their theoretical framework from French postmodernist philosophy (including Lacan, Foucault, Derrida).

Prerequisites

After delineating possible routes to the required psychopathological vocabulary and discussing possible stumbling blocks to the project (prejudices), Jaspers discussed

the necessary prerequisites for successful engagement in

psychopathology. Firstly, it is necessary to be thoroughly

competent in its specific methodology and its application (Beherrschen der Methode). Secondly, openness

and the ability to see and experience are required

(Offenheit, Seh- und Erlebensfhigkeit). Thirdly, all prejudices must be eliminated. Finally, one must possess the

capacity for self-criticism (Selbstkritik).

Methods

Psychopathological methodology is divided by Jaspers into

technical and logical aspects. The technical methods

consist of casuistics (in contrast to the practice of an everincreasing number of modern psychiatric journals, whose

Page 4 of 5

editors consider case reports as unworthy of publication),

statistics, and experiments.

The logical methods include the apprehension of individual phenomena (Auffassung von Einzeltatsachen), that

is, phenomenology; the examination of contexts and

relations (Erforschung von Zusammenhngen), leading

Jaspers to his well-known differentiation between understanding (verstehen; that is, examination of the subjective

inner world) and explaining (erklren, examination of

the objective outer world, and thereby the main focus of

so-called biological psychiatry); and the embracement

of the whole (Ergreifen der Ganzheit).

Errors

By discussing possible errors which might lead psychopathological (and other) research astray (Abwege), Jaspers

anticipated several problems within the theoretical

framework of current psychiatry that have still not been

solved:

According to Jaspers, the key problems are related to being overpowered by boundlessness (berwltigung durch

die Endlosigkeit). In this context he cited the infinitude of

case histories, the endless enumeration of the countable

(Zhlbares zhlen), the infinitude of correlations and of

elements, combinations and permutations. He further

mentioned the infinitude of auxiliary constructions

(Hilfskonstruktionen) and of potentialities (Endlosigkeit

des Allesmglichen). He further criticized the risk of literary endlessness (literarische Endlosigkeit), thereby anticipating the modern madness of publish or perish.

Two further errors to be avoided were becoming

bogged down by dogmatism (Festfahren in der

Verabsolutierung), that is, the risk of doctrinism that is especially virulent in academic circles where psychopathology is taught as a school of thought (such as the

Leonhard school [14], the Heidelberg school etc.); and

sham insights through inappropriate use of terminology

(Scheineinsicht durch Terminologie), a problem that haunts

commissions established to edit consensus-based classification criteria, the ever increasing number of new editions of which represents little more than faux progress

and a deceptive advance of psychiatry.

Conclusion

For Jaspers, psychopathology consisted of methodology and

methodological criticism. He defined methodology as the

combination of methodological consciousness and methodological system (Ordnung), as the principle of classification (Gliederung), and as isolation of the single

methods as well as the whole picture (Gesamtbild). This is

the central narrative of his work. It is accordingly a misunderstanding to identify his thought with phenomenology,

biology or the difference between them (as has often been

in the course of the reception of his work). Like early

Thome Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 2:3

http://www.jmolecularpsychiatry.com/content/2/1/3

Socratic dialogues, the General Psychopathology appears

to end aporetically regarding the issue of how firm results

can be obtained within this definition of psychopathology.

Jaspers, however, believes that at least an approach to

(Annherung) and an encircling (Einkreisen) of universal

truth is, at least in principle, possible [15]. This hermeneutic circle also requires acceptance of open questions

regarding knowledge (offene Erkenntnisfragen) and an

awareness of ones own limits (Grenzen). The experience

of limits or border situations (Grenzerfahrung) is a central

term of Jasperss philosophy [16], and therefore also of his

psychopathology.

Jaspers respected the achievement of the natural sciences, but rejected empty verbal formula (as are sometimes peddled in the humanities). Natural sciences are

for him not an alternative to psychopathology, but an integral component of it.

Psychopathology as defined by Jaspers is thereby a

chance for molecular psychiatry to look beyond its own

biologistic borders and to overcome its solipsism, frustration, and lack of orientation. Psychopathology can assist finding answers to essential questions that cannot be

addressed by neurobiological means alone, but are fundamental to psychiatry.

Page 5 of 5

14. Leonhard K: Aufteilung der endogenen Psychosen und ihre differenzierte

tiologie. In 7th edition. Edited by Beckmann H. Stuttgart, New York: Georg

Thieme Verlag; 1995.

15. Thome J: The Problem of Universalism in Psychiatry. In Philosophy and

Psychiatry. Edited by Schramme T, Thome J. Berlin, New York: Walter de

Gruyter; 2004:131140.

16. Jacobs KA, Thome J: Zur Freiheitskonzeption in Jaspers

Psychopathologie. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2003, 71:509516.

doi:10.1186/2049-9256-2-3

Cite this article as: Thome: Centenary of Karl Jasperss general

psychopathology: implications for molecular psychiatry. Journal of

Molecular Psychiatry 2014 2:3.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interest.

Received: 31 December 2013 Accepted: 16 April 2014

Published: 16 May 2014

References

1. Thome J: Zur Rolle der Psychopathologie im Zeitalter der Molekularen

Psychiatrie. In Impulse fr Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Psychosomatik in

der Lebensspanne. Festschrift zum 75. Geburtstag von Herrn Prof. Dr. Klaus

Ernst, Rostock. Edited by Hppner J, Schlfke D, Thome J. Berlin: MWV

Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2011:1929.

2. Jaspers Karl. http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Jaspers.

3. Hfner H: Karl Jaspers. 100 Jahre Allgemeine Psychopathologie.

Nervenarzt. in press.

4. Jaspers K: Allgemeine Psychopathologie. 1st edition. Heidelberg, Berlin:

Springer-Verlag; 1913.

5. Jaspers K: Allgemeine Psychopathologie. 5th edition. Heidelberg, Berlin:

Springer-Verlag; 1948.

6. Nestler EJ: The Origins of Molecular Psychiatry. Journal of Molecular

Psychiatry 2013, 1:3.

7. Ngounou Wetie AG, Sokolowska I, Wormwood K, Beglinger K, Michel T,

Thome J, Darie CC, Woods AG: Mass spectrometry for the detection of

potential psychiatric biomarkers. Journal of Molecular Psychiatry 2013, 1:8.

8. Thome J: Molekulare Psychiatrie. Theoretische Grundlagen, Forschung und

Klinik. Mit einem Geleitwort von Eric J. Nestler. Verlag Hans Huber: Bern,

Gttingen, Toronto, Seattle; 2005.

9. Thome J: Conceptualising molecular psychiatry and translational

psychiatry. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011, 12(Suppl 1):35.

10. Thome J: Humanities and Molecular Psychiatry. In Philosophy and

Psychiatry. Edited by Schramme T, Thome J. New York: Walter de Gruyter;

2004:176187.

11. Crow TJ: The big bang theory of the origin of psychosis and the faculty

of language. Schizophr Res 2008, 102:3151.

12. Churchland PS: Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind/Brain.

Cambridge, London: The MIT Press; 1989.

13. Maj M: Mental disorders as brain diseases and Jaspers legacy. World

Psychiatry 2013, 12:13.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

You might also like

- Psychotherapeutics and The Problematic Origins of Clinical Psychology in AmericaDocument5 pagesPsychotherapeutics and The Problematic Origins of Clinical Psychology in AmericajuaromerNo ratings yet

- Ib History Command Term PostersDocument6 pagesIb History Command Term Postersapi-263601302100% (4)

- General Psychopatology Vol I - K. J. (1997)Document279 pagesGeneral Psychopatology Vol I - K. J. (1997)Livia Santos100% (1)

- Skills Redux (10929123)Document23 pagesSkills Redux (10929123)AndrewCollas100% (1)

- The Nature of Psychotherapy A Critical Appraisal - NodrmDocument68 pagesThe Nature of Psychotherapy A Critical Appraisal - Nodrmcetinje100% (1)

- Karl Jaspers - General Psychopathology (1963, University of Chicago Press) - Libgen - LiDocument964 pagesKarl Jaspers - General Psychopathology (1963, University of Chicago Press) - Libgen - LiAndreea MoiseNo ratings yet

- CT SizingDocument62 pagesCT SizingMohamed TalebNo ratings yet

- Similarities and Differences Between The Schools of PsychotherapyDocument41 pagesSimilarities and Differences Between The Schools of PsychotherapyShaowan Zhang73% (11)

- Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 3: The Psychogenesis of Mental DiseaseFrom EverandCollected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 3: The Psychogenesis of Mental DiseaseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- DSM and PhenomDocument5 pagesDSM and PhenomgauravtandonNo ratings yet

- Istoria Psihologiei Experimentale in RomaniaDocument10 pagesIstoria Psihologiei Experimentale in Romaniaramona botaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Modern PsychologyDocument2 pagesA Brief History of Modern Psychologyzeddari0% (2)

- Theory of The NeurosesDocument80 pagesTheory of The Neurosesjosue ibarraNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological PsychologyDocument36 pagesPhenomenological PsychologyCatriel FierroNo ratings yet

- 01 Philosophy and PsychiatryDocument6 pages01 Philosophy and PsychiatryLindaNo ratings yet

- E Flight Journal Aero Special 2018 Small PDFDocument44 pagesE Flight Journal Aero Special 2018 Small PDFMalburg100% (1)

- Hep Overview For DMKDocument18 pagesHep Overview For DMKDaniel - Mihai LeşovschiNo ratings yet

- Service Manual: SV01-NHX40AX03-01E NHX4000 MSX-853 Axis Adjustment Procedure of Z-Axis Zero Return PositionDocument5 pagesService Manual: SV01-NHX40AX03-01E NHX4000 MSX-853 Axis Adjustment Procedure of Z-Axis Zero Return Positionmahdi elmay100% (3)

- Role of Losses in Design of DC Cable For Solar PV ApplicationsDocument5 pagesRole of Losses in Design of DC Cable For Solar PV ApplicationsMaulidia HidayahNo ratings yet

- The Biopsychosocial Model in Psychiatry A CritiqueDocument8 pagesThe Biopsychosocial Model in Psychiatry A CritiquePetar DimkovNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDocument63 pagesChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNo ratings yet

- Psychosomatic As We KnowDocument5 pagesPsychosomatic As We Knowrqi11No ratings yet

- Monergism Vs SynsergismDocument11 pagesMonergism Vs SynsergismPam AgtotoNo ratings yet

- Medard Boss-Psychoanalysis and DaseinanalysisDocument162 pagesMedard Boss-Psychoanalysis and DaseinanalysisFrancesca Carballo100% (6)

- KrausDocument352 pagesKrausIlaria PrataliNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological PsychiatryDocument9 pagesPhenomenological Psychiatryferny zabatierraNo ratings yet

- Giorgi-2003-Descriptive Phenomenological Psychological Method PDFDocument31 pagesGiorgi-2003-Descriptive Phenomenological Psychological Method PDFAngie Paola Monsalve RuizNo ratings yet

- IntegrativePsychotherapyinANutshell PDFDocument10 pagesIntegrativePsychotherapyinANutshell PDFAnca PanaitNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatric Study of Jesus: Exposition and CriticismFrom EverandThe Psychiatric Study of Jesus: Exposition and CriticismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Jaspers 100 Fuchs2013Document2 pagesJaspers 100 Fuchs2013Amàr AqmarNo ratings yet

- Existencialsmo en Psicopatologia en JasperDocument26 pagesExistencialsmo en Psicopatologia en JasperCamargo Landa XavierNo ratings yet

- Interpretacion Del Existencilaismo y Fenomenologia en PsicologiaDocument26 pagesInterpretacion Del Existencilaismo y Fenomenologia en PsicologiaCamargo Landa XavierNo ratings yet

- Psychopathology Consensus StatementDocument8 pagesPsychopathology Consensus Statementscabrera_scribdNo ratings yet

- A New Intellectual Framework For PsychiatryDocument13 pagesA New Intellectual Framework For PsychiatryLucía PerettiNo ratings yet

- Rev Chil NeuroDocument19 pagesRev Chil NeuroFrancis MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Husserl and FreudDocument83 pagesHusserl and FreudLeandro RanieriNo ratings yet

- Biologizing Social FactsDocument21 pagesBiologizing Social Factsblatg9507No ratings yet

- The Phenomenology of Psychoses (Tatossian) - For MPG WebsiteDocument85 pagesThe Phenomenology of Psychoses (Tatossian) - For MPG WebsitejaahitaNo ratings yet

- One Hundred Years of Limited Impact of Jaspers .1Document9 pagesOne Hundred Years of Limited Impact of Jaspers .1nadialeloNo ratings yet

- A New Intellectual Framework For PsychiatryDocument18 pagesA New Intellectual Framework For PsychiatryCarolina PDNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Psychosis - Historical and Phenomenological AspectsDocument11 pagesThe Concept of Psychosis - Historical and Phenomenological AspectsDaniel OconNo ratings yet

- 951-Texto Do Artigo-879-1-10-20200120Document22 pages951-Texto Do Artigo-879-1-10-20200120Matheus Pereira CostaNo ratings yet

- Landmarks in The Evolution of Experiment PDFDocument7 pagesLandmarks in The Evolution of Experiment PDFBuciu TiberiuNo ratings yet

- German Psychosomatics 2018Document11 pagesGerman Psychosomatics 2018ccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- Psychopathology Consensus StatementDocument9 pagesPsychopathology Consensus StatementAgustin307No ratings yet

- 1 BMCDocument23 pages1 BMCRPh FarhatainNo ratings yet

- Towards A Better Understanding of The Philosophy of PsychologyDocument22 pagesTowards A Better Understanding of The Philosophy of PsychologyEbook AtticNo ratings yet

- Review Article: The Concept of Schizophrenia: From Unity To DiversityDocument40 pagesReview Article: The Concept of Schizophrenia: From Unity To DiversityAnthony HalimNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Psychosis: Historical and Phenomenological AspectsDocument12 pagesThe Concept of Psychosis: Historical and Phenomenological Aspectspop carmenNo ratings yet

- Mayer Gross Textbook 3e Review Bjp1990Document2 pagesMayer Gross Textbook 3e Review Bjp1990Amàr AqmarNo ratings yet

- Welie 1995Document32 pagesWelie 1995Matheus Pereira Costa100% (1)

- Taking The Long View An Emerging FramewoDocument8 pagesTaking The Long View An Emerging FramewoilldefinedmindsNo ratings yet

- Peripatetic Group Therapy Phenomenology and PsychopathologyFrom EverandPeripatetic Group Therapy Phenomenology and PsychopathologyNo ratings yet

- Englander M - Phenomenological Psychology and Qualitative Research-S11097-021-09781-8Document29 pagesEnglander M - Phenomenological Psychology and Qualitative Research-S11097-021-09781-8Cristina RNo ratings yet

- Letters: The Social Brain: A Unifying Foundation For PsychiatryDocument2 pagesLetters: The Social Brain: A Unifying Foundation For Psychiatrycalmeida_31No ratings yet

- Hirschmuller 2008 Sigmund Freud and The History of Anna o Reopening A Closed Case by Richard A Skues (Basingstoke andDocument4 pagesHirschmuller 2008 Sigmund Freud and The History of Anna o Reopening A Closed Case by Richard A Skues (Basingstoke andvanessa saNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and PsDocument2 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and PsPablo Sepulveda AllendeNo ratings yet

- Is There A Place For Psychedelics in Philosophy. Fieldwork in Neuro and Perennial Philosophy - Nicolas LanglitzDocument12 pagesIs There A Place For Psychedelics in Philosophy. Fieldwork in Neuro and Perennial Philosophy - Nicolas LanglitzSander BroersNo ratings yet

- Freud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyDocument19 pagesFreud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyozuluokeoluchukwuNo ratings yet

- The Reach of Mind - Essays in Memory of Kurt Goldstein - Marianne L. Simmel (Auth.), Marianne L. Simmel (Eds.) - 1, 1968 - Springer-Verlag Berlin - 9783662402658 - Anna's ArchiveDocument297 pagesThe Reach of Mind - Essays in Memory of Kurt Goldstein - Marianne L. Simmel (Auth.), Marianne L. Simmel (Eds.) - 1, 1968 - Springer-Verlag Berlin - 9783662402658 - Anna's Archive張浩淼No ratings yet

- Shreya and RitikaDocument7 pagesShreya and RitikaRitika SenNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia - Sick search engine the brain: Neurotic-psychotic developments: When the soul "googles" and the memory delivers increasingly irrational search resultsFrom EverandSchizophrenia - Sick search engine the brain: Neurotic-psychotic developments: When the soul "googles" and the memory delivers increasingly irrational search resultsNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Dualism of Soma and Psyche - AisensteinDocument25 pagesBeyond The Dualism of Soma and Psyche - AisensteinStelios MakrisNo ratings yet

- Viktor Emil Von Gebsattel On The Doctor-Patient RelationshipDocument50 pagesViktor Emil Von Gebsattel On The Doctor-Patient RelationshipvstevealexanderNo ratings yet

- Applied Psychology 2Document4 pagesApplied Psychology 2sinknswimNo ratings yet

- Engstrom-Kraepelin Inaugural Dorpat LectureDocument14 pagesEngstrom-Kraepelin Inaugural Dorpat LectureraballusNo ratings yet

- Strucure Design and Multi - Objective Optimization of A Novel NPR Bumber SystemDocument19 pagesStrucure Design and Multi - Objective Optimization of A Novel NPR Bumber System施元No ratings yet

- Residual Power Series Method For Obstacle Boundary Value ProblemsDocument5 pagesResidual Power Series Method For Obstacle Boundary Value ProblemsSayiqa JabeenNo ratings yet

- Vendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Document6 pagesVendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Chelsea EsparagozaNo ratings yet

- BNF Pos - StockmockDocument14 pagesBNF Pos - StockmockSatish KumarNo ratings yet

- Tetralogy of FallotDocument8 pagesTetralogy of FallotHillary Faye FernandezNo ratings yet

- 3 ALCE Insulators 12R03.1Document12 pages3 ALCE Insulators 12R03.1Amílcar Duarte100% (1)

- 8.ZXSDR B8200 (L200) Principle and Hardware Structure Training Manual-45Document45 pages8.ZXSDR B8200 (L200) Principle and Hardware Structure Training Manual-45mehdi_mehdiNo ratings yet

- Law of EvidenceDocument14 pagesLaw of EvidenceIsha ChavanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 ComprogDocument25 pagesLesson 6 ComprogmarkvillaplazaNo ratings yet

- Regions of Alaska PresentationDocument15 pagesRegions of Alaska Presentationapi-260890532No ratings yet

- OZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1Document16 pagesOZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1aryan9411No ratings yet

- Duavent Drug Study - CunadoDocument3 pagesDuavent Drug Study - CunadoLexa Moreene Cu�adoNo ratings yet

- Global Geo Reviewer MidtermDocument29 pagesGlobal Geo Reviewer Midtermbusinesslangto5No ratings yet

- Chemistry Form 4 Daily Lesson Plan - CompressDocument3 pagesChemistry Form 4 Daily Lesson Plan - Compressadila ramlonNo ratings yet

- UC 20 - Produce Cement Concrete CastingDocument69 pagesUC 20 - Produce Cement Concrete Castingtariku kiros100% (2)

- Quantitative Methods For Economics and Business Lecture N. 5Document20 pagesQuantitative Methods For Economics and Business Lecture N. 5ghassen msakenNo ratings yet

- School of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1Document2 pagesSchool of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1STEM Education Vung TauNo ratings yet

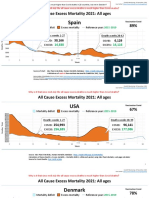

- Countries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021Document21 pagesCountries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021robaksNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson Plannicole rigonNo ratings yet

- Ricoh IM C2000 IM C2500: Full Colour Multi Function PrinterDocument4 pagesRicoh IM C2000 IM C2500: Full Colour Multi Function PrinterKothapalli ChiranjeeviNo ratings yet

- Mastertop 1230 Plus PDFDocument3 pagesMastertop 1230 Plus PDFFrancois-No ratings yet

- Sba 2Document29 pagesSba 2api-377332228No ratings yet