Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vocational Aspirations of Chinese High School Students and Their Parents Expectations (Hou & Leung, 2011)

Uploaded by

Pickle_PumpkinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vocational Aspirations of Chinese High School Students and Their Parents Expectations (Hou & Leung, 2011)

Uploaded by

Pickle_PumpkinCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Vocational Behavior

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j v b

Vocational aspirations of Chinese high school students and their

parents' expectations

Zhi-jin Hou a,, S. Alvin Leung b

a

b

Beijing Normal University, China

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 December 2010

Available online 26 May 2011

Keywords:

Vocational aspirations

Parental expectation

Family inuence

a b s t r a c t

This study examined the vocational aspirations and parental vocational expectations of high

school students and their parents (1067 parentchild dyads). Participants completed a

demographic questionnaire and an Occupations List. The Occupations List consisted of 126

occupational titles evenly distributed across the six Holland types. Parents were asked to check

the occupations that they expected their children to pursue and students were asked to select

occupations to which they aspired. The expectations of parents were compared to the aspirations of children according to the occupational field, prestige, and sextype of occupations.

The expectationaspiration gap was relatively small for occupational field, but the gap was

larger for occupational prestige and sextype. There were also gender differences for both

expectations (parents' expectation toward sons and daughters) and aspirations (aspirations of

male and female students). Types of high school (key or regular high schools) and parental

educational background also related to expectations and aspirations. Theoretical, research, and

practice implications are discussed.

2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Adolescent career aspirations are inuenced by many factors, including family, school, and socialcultural experiences. In some

cultures (e.g., Asian cultures), the career aspirations of individuals are strongly inuenced by one's family and social systems,

especially the expectations of parents (e.g., Leung, Hou, Gati, & Li, 2011; Li & Kerpelman, 2007; Otto, 2000; Tucker, Barber, & Eccles,

2001; Whiston & Keller, 2004). Although the effects of family and parental expectations on career choice have been examined in

previous research, no research study has examined the relations between parental career expectations and the career aspirations

of their children. To ll this important yet neglected research gap, we asked parents in Beijing, China, to report their expectations

of their children's career choices, and we asked their children to report their career aspirations. Corresponding parental

expectations and children's career aspirations were then analyzed and compared. The results of this study reveal the complexity of

parental expectations and how they impact the career aspirations of children.

Career aspiration was dened by Rojewski (2005) as the degree of attraction toward or preference for a particular occupation

(p. 133). Career aspiration could be viewed as one's evolving career goals, ideals, and intention toward the future that serve as a

guide for present behavior. Career expectation is a related yet different construct. Whiston and Keller (2004) dened it as the

occupations an individual believes he or she will most likely enter (p. 519). A young person's career expectations are inuenced

by his/her aspirations, and low aspirations are likely to result in restricted choices. Based on previous conceptualizations (Leung &

Harmon, 1990; Rojewski, 2005; Whiston & Keller, 2004), vocational aspiration is conceptualized in this study as occupational

Corresponding author at: School of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China. Fax: +86 10 58802102.

E-mail address: zhijinhou@163.com (Z. Hou).

0001-8791/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.008

350

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

alternatives that young people have considered, and parental vocational expectation as occupations that parents wanted their

children to pursue in the future based on their assessment of the reality.

1.1. Family inuence on career aspiration

Developmental theories such as the ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and developmental contextualism

(Vondracek, Lerner & Schulenberg, 1986) have considered family to be a crucial contextual variable inuencing the development

of adolescents and their careers. Family systems theory also emphasizes family rules and myths that serve to inuence children's

career decision-making and the values (Bratcher, 1982). Whiston and Keller (2004) reviewed more than 70 studies on how family

inuenced career development, and found that the inuence of family occurred at different developmental periods across the

lifespan. They concluded that family structure (e.g. parental educational level) and family process (e.g. parental expectations)

were two interdependent family contextual factors that should be further explored in career development research.

Research studies revealed that parents play a major, active role in adolescents' career development. For example, Isaacson and

Brown (2000) found that parents could shape children's view on work and career (e.g., as role models), and parents' attitudes

toward different occupations are instrumental in forming children's stereotypes about occupations. Young, Friesen, and

Dillabough (1991) found that parents used ve channels to inuence children's career development: open communication

between parents and children, the development of responsibility of young people, the active involvement of parents in the lives of

children, the encouragement of autonomy, and providing specic direction and guidance to children. Parents also serve as

consultants to their children (Otto, 1996; Sebald, 1986; Youniss, 1986) when children and adolescents tackle future-oriented

problems related to education and career choices. Through these different channels, parents communicate their expectations

toward their children's vocational choices.

The general conclusion from studies on parental career expectations suggests that parental expectations are often facilitative

and positive. Wilson and Wilson (1992) examined how family and school environment inuenced the educational aspirations of

high school seniors and found that parents' educational level, and aspirations had signicant effects on adolescent aspirations.

Mau and Bikos (2000) conducted a longitudinal study of the educational and vocational aspirations of 10th-grade students. They

used a nationally (in U.S.) representative sample and found that (a) parental educational expectations had a positive inuence on

students' aspirations, (b) academic track and school type were the two strongest predictors of educational and occupational

aspirations, and (c) Asian Americans and Asian immigrants perceived higher parental educational expectations than White

American students. In another longitudinal study, Mau (2003) found that students who persisted in science and technology

2 years beyond high school perceived higher parental expectations in high school than students who switched to other areas. The

positive effects of parental expectations on adolescents' career goals and aspirations were echoed by Massey et al. (2008) who

reviewed 94 research studies and concluded that high parental expectations for children associated with high educational and

career aspirations.

The inuence of parents on the career aspirations of children also varied across culture. In Asian cultures where obedience and

family obligations are strongly emphasized, the effects of family on the career choice and behavior of individuals are likely to be

magnied. Parental expectations have been suggested as a potential obstacle to adolescent career choice and development. For

instance, Chao and Sue (1996) found high expectation for children's educational and vocational development to be one of the

major characteristics of the relationship between parents and their children. Leong and Seraca (1995) reviewed the research

studies on the career development of Asian Americans and found that Asian-American adolescents perceived higher parental

pressure than their Euro-American peers. Asian-American participants reported that their parents often exerted a direct inuence

on their career aspirations and career choices, which caused them to limit to options to those careers that would satisfy their own

interest and meet parents' expectation. Leung et al. (2011) found that the career decision-making difculties of university

students in China related to the perceived levels of parental expectations and their perceived performance in the areas where

expectations were directed.

Understanding the dynamic interaction between parental vocational expectation and student career aspiration is particularly

important in modern China. First, parental expectations are supported and elevated to high salience by traditional cultural values

such as lial piety, loyalty to family, and obedience to parents. Second, Chinese individuals have only been granted recently the

freedom to choose their own occupations (Leung et al., 2011) and parents are the major social support for children in their

vocational concerns. Third, family expectations toward children's career development have been magnied in modern China

where the only child becomes the focus of family attention in a 4:2:1 family structure (four grandparents, two parents, and one

child). Therefore, China offers a unique cultural context to study how parental expectations might facilitate or impede the career

aspirations of their children.

1.2. Gottfredson's theory and conceptualization of career aspirations

Gottfredson's (1981, 1996, 2002) theory of career aspiration is used as the theoretical framework for this study. She suggested

that individuals progressively eliminate career alternatives in a developmental process based on sextype and prestige (a process of

circumscription), and they only consider the t of occupations with personal characteristics within their levels of acceptable

occupational prestige and sextype (i.e., zone of acceptable alternatives). Whereas the aim of this study is not to test the theory by

Gottfredson (1981, 1996), the importance attached to, and the conceptualization of career aspirations in terms of prestige,

sextype, and eld of interest were grounded in Gottfredson's theory (e.g., Leung & Harmon, 1990; Leung, Ivey, & Suzuki, 1994).

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

351

Occupational prestige and sextype are important variables to consider in assessing the career aspirations of Chinese students,

especially among Asian Chinese students (e.g., Leung, 1993; Leung et al., 2011; Zhang, Hu, & Pope, 2002). Parental and family

expectations could shape their children's attitudes toward occupational status and gender-type. Children might aspire to

occupational alternatives that are within their parents' approved or expected levels of prestige and sex-type before considering

the compatibility between self and occupational alternatives (Gottfredson, 1981, 1996).

Accordingly, this study examined the correlates between parental expectations and children's career aspirations by asking both

Chinese parents and children to report their expectations and aspirations simultaneously. Vocational aspirations are referred to as

the occupational alternatives that students have considered, and parental expectations are referred to occupational alternatives

that parents wanted their children to attain within their social reality (Leung & Harmon, 1990; Rojewski, 2005; Whiston & Keller,

2004). The aspired and expected occupations are coded according to their levels of prestige, sextype, and eld of interest for the

purpose of analysis and comparison. High school students are chosen as participants as they are more likely than other populations

to be inuenced by parents (e.g., college students typically would live away from home and would feel more independence).

1.3. Research questions and hypotheses

Three clusters of hypotheses are tested. First, we examined differences between students' career aspirations and the

expectations of their parents in terms of prestige, sextype, and occupational eld (to examine if there is an expectation and

aspiration gap). We coded occupational aspirations and expectations with indexes of prestige, sex-type, and eld of work which

are the three main factors addressed by Gottfredson (1981, 1996) in her theory of career aspiration. Previous studies suggested

that parental expectations correlate positively with the students' aspirations (Conklin & Dailey, 1981; Helwig, 1998; Mau, 1995;

Wilson & Wilson, 1992), but none has examined the difference between parental expectations and children's aspirations on

multiple dimensions. Accordingly, the rst hypothesis stated that there is no signicant difference between children's occupational aspirations and parental expectations in prestige, sex-type, and occupational eld.

Second, previous research studies quite consistently showed gender differences on career interest (e.g., Hwang, Kim, Ryu, &

Heppner, 2006; Leung & Hou, 2001) and preferences for sextype and prestige (Hannah & Kahn, 1989; Henderson, Hesketh &

Tufn, 1988; Leung & Harmon, 1990). Hence, we expect that (a) there would be gender differences on children's career

aspirations, and (b) that parents have different expectations toward their male and female children. The gender differences are

revealed in the prestige, sextype, and occupational eld of aspired and expected occupations.

Third, we hypothesized that both aspirations and expectations relate to the academic competence of students (Creed, Conlon &

Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007; Marjoribanks, 2002). In China, all students must take a state academic entrance test when they enter high

school. Students who attain higher scores go to key high schools (schools with high achieving students), and others go to regular

high schools (schools with regular achievers). Accordingly, we hypothesized that key high school students have aspirations that are

higher in prestige levels (e.g., consider higher prestige occupations with a narrow range of prestige occupations) than those of

regular high school students. Similarly, parental career expectations toward children in the two types of high schools are likely to

differ in the same direction as the children's. In addition to the above, we also hypothesized that parental educational level plays a

role in affecting the aspirations of students.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants of this study were recruited from nine different junior and senior high schools in Beijing. High school students in

Beijing were tracked into different schools based on students' academic achievement. Five of the nine participating high schools

consisted of high achieving students, while the remaining four high schools consisted of students who were tracked as regular

achievers. There was a total of 1067 studentparent dyads (482 dyads were ninth graders and parents, and 585 dyads were

twelve graders and parents), and 467 students were male (corresponding parents were 225 fathers and 239 mothers) and 600

were female (corresponding parents were 222 fathers and 372 from mothers). Nine parents did not indicate whether they were

mother or father. The mean age of students was 15.8 (SD = 1.61). Key high school students (n = 671) consisted of 289 males (126

9th graders and 163 12th grader) and 382 females (133 9th graders and 249 12th graders). Regular high school students (n = 396)

consisted of 178 males (96 9th graders and 82 12th graders) and 218 females (127 9th graders and 91 12th graders). Of all the

parents, 52.6% (n = 561) had less than a college education, 46.8% (n = 499) had college education or above, and 0.6% (n = 7) did

not report their education level.

2.2. Measures

The Occupations ListChinese Version (OLC) used in this study was revised from the Occupations List (OL) used by Leung and

Harmon (1990), which consisted of 161 occupational titles. In this study, each title was translated into Chinese, but back

translation procedure was not used because the OL consisted of occupational titles that were not ambiguous in meaning. Instead,

two postgraduate students who had a comprehensive knowledge of the occupational system in China were asked to review the

contextual relevance of the titles. Titles that were considered to be unfamiliar or unusual to Chinese (24 items, e.g. missionary,

rancher) were deleted. Some occupational titles were adapted and revised to t with Chinese occupational context. For example,

352

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

English teacher, foreign language teacher and social science teacher were combined into humanity subject teacher. This process

resulted in the fusion of 30 occupational titles into 12 titles. A total of 119 titles in the OLC were retained.

The 119 occupations of the OLC were then classied into the 6 Holland interest types based on the 3-letter Holland interest

codes assigned by Leung, Ivey and Suzuki (1994) to occupational titles. To have the same number of items in each of the six

Holland types, 13 new occupational titles were added to the list. The 13 titles were (a) considered to be common occupations in

China, and (b) referenced from occupational items listed in the Vocational Preference Inventory (VPI; Holland, 1985) and Selfdirected Search (SDS; Holland, 1994a). The Holland codes of these 13 occupations were obtained by consulting the Occupations

Finders (Holland, 1994b). The 132-item version of the OLC was piloted with a group of Beijing high school students, and six titles

that students had difculty understanding were deleted. The nal OLC used in this study consisted of 126 occupational titles, with

21 titles each representing the 6 Holland occupational types.

2.3. Procedure

School administrators in the nine participating schools were contacted and permission was obtained to distribute the

questionnaires for this study. Students were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire and an Occupations ListChinese

version (OLC; Leung & Harmon, 1990). They were requested to bring a set of the questionnaires home and ask one parent to

complete the parent version of the OLC, and then put them into an envelope to return it to the researcher. Students and parents

were both informed of the purposes of this study, and that participation was voluntary and that they could elect not to participate

(e.g., by not returning the questionnaires back to the researcher). Identication information was removed from the questionnaires

once the corresponding codes were assigned to students and their parents. Students and parents had different instructions when

lling out the OLC. Students were asked to indicate from the OLC occupations that they have daydreamed or considered to pursue

in the future, while parents (participants had to indicate if respondent was father or mother) were asked to indicate occupations

that they wanted their children to pursue in the future. A total of 1364 set of parentstudent questionnaires were sent and 1258

students and 1137 parents returned completed questionnaires. After eliminating questionnaires where only the parent or the

child completed, a total of 1067 parentchild dyads were included in data analyses (78% of questionnaires distributed).

In addition to the above, a different group of parents and students were recruited to rate either the prestige or sextype levels of

occupations in the OLC. A total of 1902 pairs of parents and students returned their ratings.

2.4. Computation of scores of expected and aspired occupations

The occupational titles in the OLC were coded into three dimensions: occupational eld, prestige, and sextype. Based on the

Holland high-point code of occupations assigned to occupations in the OLC, we computed the distribution (in percentages) of

expectations and aspirations along the six Holland occupational themes (that is, the occupational eld of occupations

expected/aspired).

Since there was no Chinese Socioeconomic Indicator similar to those developed in the U.S. (Stephens & Featherman, 1981) and

there was no detailed census information in China to develop indicators of occupational prestige and sextypes, we used people's

subjective perception as indicators of occupational prestige and sextype. This method was used in the literature to determine the

sex stereotypes of occupations (Shinar, 1975). A total of 954 students and their parents were asked to evaluate their perception of

the social prestige of each occupation in OLC on a 5-point Liker scale, and another 948 students and their parents were asked to

evaluate the sextype of the occupations. A total of 1609 students and 1736 parents returned their evaluations. For each occupation,

prestige or sextype scores obtained from all participants were averaged respectively, and then were transformed into a 0 to 100

scale (1 = 0, 5 = 100, step = 25) as the prestige index and sex-type index of occupations. We did this transformation aiming to

extend the scales and to make a ner distinction of occupational sextype and prestige. The value of prestige index ranged between

25.72 (lowest prestige) and 86.49 (highest prestige) and the value of sextype ranged female 9.51 (female dominant) and 90.68

(male dominant). Ratings of parents and children were combined to form a single rating that takes both perspectives into

consideration.

We adopted the method used by Leung and Harmon (1990) to compute prestige and sextype preference scores, and to serve as

operational denitions of occupational space which Gottfredson (1981, 1996) called the zone of acceptable alternatives. The zone

of acceptable alternative was dened by Gottfredson (1996) as the range of alternatives in the cognitive map of occupations that

the person considers acceptable (p. 187). Accordingly, four scores were computed from the OLC for each participant to reect the

prestige levels of parental expectation and children's aspiration: (a) highest PR score, which is the score of the occupation that has

the highest prestige score among those expected/aspired (that is, top boundary of expectation/aspiration); (b) lowest PR score,

which is the score of the occupation that has the lowest prestige score among those expected/aspired (that is, low boundary of

expectation/aspiration); (c) the PR range score, which is the arithmetic difference between the highest PR score and the lowest PR

score; and (d) mean PR score, which is the mean of all the occupations expected/aspired.

Similarly, four sextype scores were computed, which are highest ST score, lowest ST score, ST range scores, and mean ST score. The

method of computation paralleled the method to compute the various prestige preference scores, except that the sextype ratings

were used instead.

The computation of scores/indicators of occupational eld, prestige, and sextype allowed comparisons between parental

expectations and children's aspirations, and for the hypotheses to be tested.

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

353

3. Results

3.1. Expectation and aspiration gap: Correspondence between parental expectations and students' aspirations

The high-point Holland code of occupations selected from OLC by participants were counted and transformed into percentages

of total number of occupations selected (e.g. if a participant selected a total of 21 occupations from the OLC and ve were Artistic

occupations, the percentage of Artistic occupations chosen would be 23.8%). The distribution of high-point expectation and

aspiration codes in percentages across the six Holland interest types are presented in Table 1. A Nonparametric test for paired

samples was conducted for each of the Holland type pairs of parent and child. Signicant differences between parental

expectations and students' aspirations were found on Realistic, Investigative, Artistic and Conventional occupations. Parents were

more likely than their children to select Investigative (z = 9.21, p b .001) and Conventional (z = 11.63, p b .001) occupations, but

students were more likely to select Realistic (z = 7.83) and Artistic (z = 11.42) occupations than their parents. Investigative

occupations were most preferred by parents (27.0%, 6 percentage points above the next highest), whereas Investigative,

Enterprise and Artistic occupations were almost equal aspired by their children (22.5%, 21.4%, and 21.6%, respectively; as seen in

Table 1). Although the percentage of each occupation type selected by parents and students differed, the order of selection was

quite similar, especially for the rst two types. The order of expected occupational types (parents) was IESACR and the order of

aspired occupational types (students) was IEASRC. The ndings suggested that students' aspirations (on eld of occupation) were

quite congruent with their parental expectations.

To examine if the prestige and sextype scores of parental expected and student aspired occupations were similar, we

performed paired t-tests for two sets of scores (total of eight scores). Eight paired t-tests were done and the results are presented

in Table 2. We observed signicant differences in all the scores. Parents had higher scores than students on the mean PR, highest

PR, and lowest PR scores, and lower score than the latter on the PR range score. Parents' prestige expectations were generally

higher than students' prestige aspirations (mean, highest and lowest prestige levels), and parents expected a smaller prestige

range than their children. For the sextypes scores, parental expectation tended to be more masculine than students' aspirations

(higher mean ST and lowest ST scores than students'). However, the highest ST and ST range scores of students were higher than

those of their parents', which suggest that students have a more exible sextype aspiration than the sextype expectations of

parents.

In conclusion, the above ndings do not support the rst hypothesis which stated that there is no difference between parental

expectation and children's aspiration. In the occupational elds considered (i.e., Holland occupational types), there was a good

degree of congruence between parental expectations and students' aspirations (that is, the expectation and aspiration gap was

relatively small), yet there were signicant differences between the two parties on their preferred occupational prestige levels and

sextype (that is, there existed a clear expectation and aspiration gap).

3.2. Parental expectations and students' aspirations gender differences

To know whether there were gender differences on expectations and aspirations (second set of hypotheses), non-parametric

tests were performed on the percentages of corresponding interest types of occupations considered in the OLC by male and female

students and of parental expectations on male and female students as seen in Table 3. Signicant gender differences on aspired

occupations were found in almost all the Holland types except for Conventional occupations. The same pattern of differences was

found in parental expectations as well. For male students, the three most aspired occupational elds were Investigative,

Enterprising and Artistic (IEA), but for female students it was Artistic, Enterprising and Investigative occupations (AEI). The three

most expected occupational elds by parents of male students were Investigative, Enterprising and Social (IES), and for parents of

female students it was Enterprising, Investigative, and Artistic (EIA). Hence, while Investigative occupations were the most

expected and aspired Holland type for parents and their male children, parents of female students expected their children to

pursue Enterprising occupations, although female students tended to aspire toward Artistic occupations.

To determine the possible parental gender effect on career expectations, ANOVA was performed with each of four prestige

(highest PR, lowest PR, PR range, and mean PR) and each of four sextypes scores (highest ST, lowest ST, mean ST, and ST range) of

parental expectations as dependent variables and parent gender and student gender as independent variables. The main effect for

Table 1

Parental expectations and students' aspirations classied into Holland types (in percentages of Holland high-point code).

Type

R

I

A

S

E

C

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

Parental expectation

Student's aspiration

z-Score

8.44

27.00

15.57

16.18

21.58

11.29

10.73

22.45

21.40

15.88

22.14

7.40

7.83

9.21

11.42

1.23

.94

11.63

(8.56)

(17.21)

(12.35)

(10.45)

(13.69)

(10.39)

(8.59)

(17.13)

(15.28)

(9.85)

(14.62)

(7.79)

Note. N = 1067 dyads of parent and child. R = Realistic, I = Investigative, A = Artistic, S = Social, E = Enterprising, C = Conventional.

p b .001.

354

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

Table 2

Means and standard deviation of the parental expectations and students' aspirations (N = 1067).

Parental expectations

Highest PR

Lowest PR

PR range

Mean PR

Highest ST

Lowest ST

ST range

Mean ST

Students' aspirations

T-value

SD

SD

84.10

48.81

35.30

67.97

78.62

37.89

40.72

61.01

4.46

11.61

12.65

5.38

7.41

13.22

16.93

5.48

83.21

40.36

42.85

66.00

81.60

33.97

47.63

60.56

4.18

11.24

10.28

4.74

7.76

13.72

16.66

5.95

5.52

25.99

19.78

11.77

10.30

8.50

11.35

2.58

Note. PR = Prestige, ST = Sex-type.

p b .01.

p b .05.

parental gender and the parental gender x student gender interaction were not signicant. The main effects for students are

reported in the analysis below.

T-tests were then done to further examine possible gender differences (prestige and sextype scores) on students' aspirations

and parental expectations of male and female, respectively as seen in Table 4. Signicant gender differences were found in almost

all prestige and sextype scores except the highest PR. Male students considered occupations of higher prestige levels than female

students. Male students scored higher than female students on lowest PR and mean PR. On the PR range score, the scores of male

students were lower than those female students. Male students considered more masculine occupations than female students.

Male students scored higher than female students on the lowest ST, highest ST, and mean ST scores, but had a smaller ST range

score than female students. A similar pattern of gender differences was found in parental expectations. Parents of male students

had a higher lowest PR and mean PR score but smaller PR range than parents of female students. Parental expectations toward

male and female students on the four sextype scores were all signicant. Except for the ST range score, parents of male students

scored higher than parents of female students on the highest ST score, lowest ST score, and mean ST score.

In summary, the ndings suggested that there were gender differences on the vocational aspirations of male and female

students, and on the expectations of parents toward male and female students. These differences were found in the occupational

eld, prestige, and sextype of occupations. These ndings supported the second set of hypotheses.

3.3. The inuence of school type and parental education level on students' career aspirations and parental expectations

MANOVA was performed with each of the four prestige aspiration scores of students (highest PR, lowest PR, PR range, and

mean PR) as dependent variables and type of schools (key high school and regular high school) and parental educational level

(college degree or higher and no college degree) as independent variables (as seen in Table 5). A main effect for school type was

found for all prestige indicators, except for the highest PR. For the lowest PR scores, the aspirations of key high school students

were signicantly higher than those of regular high school students. Also, key high school students had a smaller PR range score

than regular high school students. The parental educational main effect was also signicant for all the prestige scores except for the

highest PR score. Students whose parents had a college education or more scored higher than students of parents with no college

education on the lowest PR and mean PR scores, but their PR range scores were lower than the latter group.

Similar MANOVAs were also performed with each of the four sextype scores on students aspiration (highest ST, lowest ST,

mean ST, and ST range) and type of schools (key high school and regular high school) and parental educational level (college

degree or higher and no college degree) as independent variables (as seen in Table 5). A main effect for school type was found in all

the ST scores. Students in key high schools were more likely to consider masculine occupations than students in regular high

Table 3

Gender effect on the parental expectations and students' aspirations in Holland type (%).

Type

Parental expectations

Male

R

I

A

S

E

C

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

10.65

32.62

11.94

14.84

19.50

10.44

z-Score

Female

(10.06)

(18.33)

(10.23)

(9.82)

(13.46)

(8.93)

6.03 (6.90)

22.63 (14.89)

18.40 (13.12)

17.22 (10.81)

23.07 (13.67)

11.96 (11.36)

Students' aspirations

Male

6.51

9.56

8.61

3.92

4.33

1.43

12.79

28.34

16.84

14.56

20.16

7.32

z-Score

Female

(9.69)

(19.34)

(15.12)

(10.11)

(15.39)

(8.84)

9.13

17.86

24.95

16.90

23.69

7.47

(7.24)

(13.52)

(14.45)

(9.53)

(13.81)

(7.14)

6.43

9.86

9.88

4.38

4.72

1.78

Note. N = 467 dyads of male student and parent; N = 600 dyads of female student and parent, R = Realistic, I = Investigative, A = Artistic, S = Social, E =

Enterprising, C = Conventional.

p b .01.

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

355

Table 4

Parental expectation and students' aspiration scores by student's gender.

Parental expectation

Highest PR

Lowest PR

PR range

Mean PR

Highest ST

Lowest ST

ST range

Mean ST

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

Mean

SD

84.39

83.88

50.12

47.79

34.28

36.09

68.95

67.21

80.08

77.48

41.77

34.88

38.31

42.60

63.47

59.09

3.72

4.95

12.06

11.16

12.85

12.44

5.30

5.32

6.47

7.88

13.04

12.57

17.15

16.53

4.22

5.59

T-value

Students' aspiration

1.93

3.27

2.33

5.32

5.78

8.71

4.12

14.55

T-value

Mean

SD

83.45

83.03

43.06

38.26

40.39

44.77

66.99

65.23

83.11

80.43

39.52

29.66

43.59

50.77

63.72

58.10

3.77

4.46

11.70

10.41

12.86

12.03

4.90

4.46

6.87

8.21

12.92

12.75

16.10

16.42

4.78

5.60

1.68

6.98

5.72

6.11

5.81

12.46

7.15

17.68

Note. N = 1067 dyads, with 467 male and 600 female students. PR = prestige, ST = sex-type, M = male, F = female.

p b .01.

p b .05.

schools. A main effect for parental education was found only in the mean ST score, and students of parents with college education

tended to consider more masculine occupations than students whose parents did not complete college education (but the trend

was not shown in all four sextype scores).

The second set of MANOVAs were performed on parents' data, with each of the four prestige expectation scores and each of the

four sextype expectations scores as the dependent variable, and school type and parental education background as independent

variables as seen in Table 6. The school type main effects were signicant in all the four prestige scores, and the parental

educational background main effects were signicant in three of the prestige score (except highest PR score). The ndings

suggested that parents from key high schools tended to have higher prestige expectation toward their children than parents of

students in regular high schools. The same trend was found between parents with and without college education.

Similarly, the school type and parental education background main effects were signicant for all the four sextype scores.

Parents of key school students and parents who completed at least a college education tended to expect their children to consider

more masculine occupations than parents from regular high school and parents who did not complete college.

We used a distance measure (D measure; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) to calculate the congruence of parental prestige and

sextype expectations with students' prestige and sextype aspirations so that additional analyses could be conducted to determine

Table 5

Students' aspiration scores by school type and parental educational level (n = 1060).

Parental educational level

College or above

n = 499

Below college

n = 561

Aspiration scores

School

SD

SD

Highest PR

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

83.06

83.08

39.67

42.78

43.39

40.30

66.03

67.05

80.24

81.98

31.86

36.58

48.38

45.40

59.97

61.77

4.37

3.96

10.26

10.92

11.65

12.19

4.24

4.40

7.68

7.22

13.53

13.84

16.41

16.93

5.64

5.62

83.29

83.30

36.80

40.94

46.49

42.35

64.34

66.22

81.11

82.02

30.66

34.38

50.45

47.64

58.89

60.76

4.46

4.13

10.82

11.59

12.34

12.90

5.08

4.54

8.73

7.36

13.40

13.01

16.51

16.13

6.61

5.26

Lowest PR

PR range

Mean PR

Highest ST

Lowest ST

ST range

Mean ST

Fb

Fa

.002

Fc

.565

.001

21.28

8.94

.429

16.72

8.50

.355

19.31

14.56

1.720

5.72

.674

.571

19.13

3.11

.270

5.99

3.32

.005

19.48

6.30

.006

Note. PR = Prestige; ST = Sex-type, R_Sch = regular high schools, K_Sch = key high schools.

a = main effect of school type; b = main effect of parental educational level; c = school type and parental educational level interaction.

p b .01.

p b .05.

356

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

Table 6

Parental expectation scores by school type and parental educational level (n = 1060).

Parental educational level

College or above

N = 499

M

Highest PR

Lowest PR

PR range

Mean PR

Highest ST

Lowest ST

ST range

Mean ST

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

R_Sch

K_Sch

Below college

N = 561

SD

83.40

84.53

41.71

52.89

35.69

31.64

66.97

69.87

77.95

77.02

36.36

42.36

41.58

35.66

60.35

62.06

5.07

3.84

11.18

10.82

12.63

11.90

5.27

4.54

8.44

6.20

12.02

12.16

15.92

15.37

5.81

4.6

M

83.23

84.66

43.24

49.16

39.97

35.50

65.11

68.65

80.92

78.57

32.52

37.71

48.39

40.86

59.40

61.41

SD

Fa

5.53

3.57

10.45

11.69

12.12

12.72

5.71

4.80

8.81

8.26

12.74

13.49

16.36

16.78

6.63

4.72

16.22

Fb

Fc

.005

.235

50.13

24.44

.221

23.91

21.84

.061

80.93

18.42

.811

9.99

19.12

38.41

22.12

.204

39.81

32.27

.071

23.33

4.31

.159

1.90

Note. PR = Prestige; ST = Sex-type, R_Sch = regular high schools, K_Sch = key high schools.

a = main effect of school type; b = main effect of parental educational level; c = school type and parental educational level interaction;

p b .01.

p b .05.

the effects of school type and parental educational level on the respective congruence levels. The distance measure could be

viewed as a measure of prole similarity in terms of level, dispersion, and shape. Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) suggested that D

is the generalized Pythagorean distance between two points in Euclidian space (p. 602). Based on this formulation, the formula

for the calculation of prestige expectation and aspiration congruence is presented below.

2

DP = HPPHPS + LPPLPS

DP2

HPP

HPS

LPP

LPS

the square of prestige distance between corresponding expectation and aspiration

highest PR of parental expectation

highest PR of students' aspiration

lowest PR of parental expectation

lowest PR of students' aspiration

The formula for the calculation of sextype congruence is presented below.

2

Dst = HSPHSS + LSPLSS

2

Dst

HSP

HSS

LSP

LSS

the square of sex-type distance between two corresponding expectation and aspiration

highest ST of parental expectation

highest ST of students' aspiration

lowest ST of parental expectation

lowest ST of students' aspiration

It should be noted that the higher the D score, the lower the congruence between expectation and aspiration. A 2 2 2 ANOVA

analysis was then conducted to determine the effects of students' gender, school type and parental educational level on each of the

two indexes of congruence (prestige and sextype). A signicant gender main effect was found. Parentmale student dyad had

signicantly higher prestige congruence (that is, lower D scores) than female dyads (F(1,1052) = 5.23, P b .05). School type

signicantly inuenced the prestige congruence of parentchild dyads (F(1,1052) = 3.78, p b .05). Parentstudent dyad from key

high schools (mean of D score = 12.92) had lower congruence than those from regular school (mean of D score = 11.14). Parental

educational level was also signicant in affecting the prestige congruence (F(1,1052) = 5.05, p b .05). Parentchild dyad with

parents had a college education or higher had a lower level of prestige congruence (mean of D score = 13.35) than parentchild

dyads with parents who had less than a college education (mean of D score = 11.29).

There was no gender and school type main effect on the D congruence score, yet the parental educational level main effect was

signicant (F(1,1052) = 6.59, p b .05). Parentchild dyads with parents who completed college had lower congruence scores

(mean of D score = 16.46) than parentchild dyads whose parents had less than a college education (mean of D score = 14.75).

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

357

In summary, the ndings using the D score of congruence revealed that the size of the expectationaspiration gap was

inuenced by gender, school type and parental education. Overall, gender of student, school type, and parental education has a

stronger effect on the prestige expectation and aspiration gap than on the sextype expectation and aspiration gap.

4. Discussion

Regarding the similarities between parental career expectation and the vocational aspirations of their adolescent children, the

ndings of this study revealed that there are both similarities and differences. Findings further suggested that the characteristics of

expectations and aspirations, as well as the congruence between, are affected by factors such as gender, academic achievement

and the educational background of parents.

Investigative, Enterprising and Artistic occupations were most preferred by male students and female students. However,

parents were more likely to expect their children to pursue Investigative (male students only) and Enterprising (both male and

female students) occupations. In addition, both Realistic and Conventional occupations were the least likely occupational groups to

be considered by both groups. There are two plausible reasons for why parents were more likely to expect Investigative occupations

for their sons. The rst reason is that Chinese parents tend to expect their children to work in scientic professional elds (Leong &

Seraca, 1995), value education, and respect scholarship. The other reason is that Chinese parents tend to see prestige as the most

important factor in selecting a job, which is expressed in a famous Chinese idiom which says to expect our sons to be a dragon. This

is a cultural portrayal of how Chinese parents want their sons to develop into powerful and accomplished men.

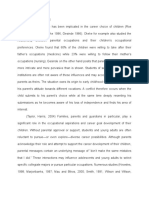

We calculated the prestige and sextype score of all the occupations in the OLC based on the subjective ratings generated in this

study and we classied them according to the six Holland types as seen in Fig. 1. Investigative and Artistic occupations have the

highest prestige levels, yet Investigative occupations were also more masculine in sextype. This might be the reasons that male

students were also most likely to aspire to Investigative occupations, while female students were most likely to aspire to Artistic

occupations. The ndings suggested that both prestige and sextype were important factors, but prestige was more critical because

both of the most sextyped occupations Realistic for males and Conventional for females were not the most aspired

occupational elds. This provides support for the prestige assumption proposed by Leung, Ivey and Suzuki (1994) when they

studied Asian Americans and found that prestige tended to be a more salient factor than sextype.

Enterprising occupations were the next most popular expected by Chinese parents and aspired by students. This is probably

due to China's economic reform in the late 1970s that resulted in cycles of business development and improvement in the

economic well-being of the average citizens. For example, undergraduate programs in business studies and MBA programs in

China are very popular, and many students enter these programs with the aspiration to make a good living for themselves and

their parents upon graduation.

We found that the expectationaspiration congruence between parents and students was higher for parent and male student

dyads than for parent and female student dyads. This could be due to two reasons. First, it is possible that parents are more likely to

place and articulate their expectations on their sons than daughters. Consequently, the aspirations of sons resembled the

expectations of parents more than daughters, and daughters perhaps are given more freedom to pursue their options. Second, in

China, sons are seen as the tradition bearer of the family and thus they have a major responsibility for keeping and advancing the

face and glory of the family. It is relatively difcult for sons to break-away from this cultural sex-role tradition.

When students' prestige and sextype aspirations were compared with parental expectations, we found signicant differences

in all eight scores. The expectationaspiration gap between the prestige and sextype expectations of parents and students'

corresponding aspirations found in this study has important implications. The expectations of parents are likely to be a two-edged

sword. On one hand, high expectations would likely facilitate the development and nurturance of high career expectations and

80

I

Prestige

70

E

S

R

60

C

50

40

50

60

70

Sextype

Fig. 1. Prestige and sex-type of occupations by Holland types.

80

358

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

attainment. On the other hand, high expectations might create burdens and goals that are difcult and impossible to fulll. The

negative impact of high expectations would put some students at risk for career-related and/or emotional difculties, such as

students whose academic competence might not be sufcient to meet high parental expectations, and students whose career

interest and/or prestige and sextype aspirations are signicantly different from those of their parents'.

We found signicant differences between male students and females in most of the prestige and sextype aspiration scores.

Although the aspirations of male and female students had similar prestige range, the highest prestige level and lowest prestige

levels of the two genders were not the same (that is, they were located in different regions of the prestige continuum). The salience

of traditional gender norms in China is further illustrated by the gender differences in parents' expectations toward sons and

daughters. The gender differences revealed that gender role expectation is still a vital force in the social and cultural norm of China,

and male students are socialized into high prestige occupations that are congruent with prevalent prestige and sextype attitudes

(e.g., parents' values). Female students displayed more exibility in their prestige and sextype aspirations yet they are likely to be

bounded by social and gender cultural norms as well.

Consistent with the positions of career development theories with a sociological emphasis (e.g., Gottfredson, 1996), students'

ability level and parent's educational background were found to have an inuence on both parental career expectations and

students' aspirations. The results are consistent with previous research (Heckhausen & Tomasik, 2002; Schoon & Parsons, 2002;

Wilson & Wilson, 1992) which found that the vocational aspirations of students were strongly tied to school performance and the

socioeconomic background of students (see Johnson & Mortimer, 2002).

The merits and potential harmful effects of educational tracking have been debated in the literature (Johnson & Mortimer,

2002). The educational tracking system in China is deeply rooted and unlikely to change. The ndings of this study revealed that

students who were tracked in key high schools had higher career aspirations than students in regular high schools, and were also

targets of high parental expectations. Whereas the aspirations of students in key high schools should be nurtured with caution, it is

equally important for government and educational professionals to be aware of the need to maintain high and positive

expectations for students in regular schools, and be aware of how their expectations might shape or ruin the aspirations of

students whose competence, efcacy, interest, and potential contributions are yet to be discovered and developed.

The theory by Gottfredson (1981, 1996) provides a useful conceptual platform to examine parental expectations and students'

aspirations. This study was not designed to test specic hypotheses derived from Gottfredson, but the variables suggested by the

theory, which are namely prestige, sextype, and eld of occupation, appeared to be critical variables in a Chinese cultural context.

The method used by Leung and Harmon (1990) to measure prestige and sextype aspiration provides an operational platform to

examine and compare parental expectations and students' aspirations. In this study, two additional sets of prestige and sextype

scores, the highest PR/SR and lowest PR/SR, offered useful additional information. Previous studies (Leung, Conoley & Scheel,

1994; Leung & Harmon, 1990) used the mean of prestige, mean of sextype, and the range of highest and lowest of both dimensions

as indicators of preferences. For instance, there might not be differences between groups on mean PR and mean ST scores, yet there

might be differences on highest and lowest scores. Similarly, there might not be difference on the PR/ST range, yet the location of

the highest and lowest prestige and sextype scores might be different. As illustrated by ndings of this study, the range of students'

prestige aspirations was similar between the two genders, yet they were located in different regions of the prestige continuum.

Such ndings suggested that multiple indicators of prestige and sextype aspirations should be employed in studying the

characteristics of career aspirations and parental expectations.

Several practice implications emerge from the ndings. First, counselors should recognize that Chinese youth are confronted

with the difcult task of making educational and career choices that they are interested in within the zone of what their parents

would accept. This is not an easy task for adolescents, especially due to the single child policy that is still implemented in major

cities (i.e., all family expectations are placed on the child) and the competition involved in the education and career

implementation process (e.g., educational tracking and insufcient jobs for college graduates). In China, the only child family is a

norm in big city, like Beijing. Parents put all their expectations on this only child, the pressure of son to be dragon and daughter to

be phoenix has already draw attention from society. In is important for counselors and educators to assist students who are

experiencing internal conicts, tensions, and anxieties, between actualizing themselves or to fulll their obligations to their

parents. Students should be encouraged to use conict resolution strategies including negotiation, compromise, and cooperation,

as well as to communicate good-will and respect (an important gesture in a Chinese society), so that parents could give way to

students' aspirations without feeling that their children are being disobedient or disrespectful (Leung & Chen, 2009).

Second, counselors should engage parents in the career development process of their children, through various formal and

informal career development intervention programs. In a Chinese society, parental concerns and expectations are often regarded

positively and taken as gesture of nurturance. If parents could participate in programs where they could understand the career and

educational needs of their children, to see the positive outcomes associated with their children's vocational aspirations, they are

more likely to appreciate the aspirations of their children. Teachers and counselors could play an important role in helping parents

and students to communicate, and provide opportunities in schools for such interaction to occur (e.g., teacherparent conferences,

career exploration events with parental participation).

Third, counselors should encourage students to expand their career interest beyond Investigative and Enterprising occupations.

Counselors should organize career exploration activities to increase students' awareness of diverse career opportunities, and the

educational pathways that would lead to the attainment of these occupations. It is equally important for teachers and parents to be

aware of multiple vocational elds, so that students could explore them with their support and blessings. The traditional Chinese ideas

that all trades and professions have their masters could be used as a culture-based rationale to encourage openness to occupational

alternatives among teachers, parents and students.

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

359

Fourth, it is important for counselors to help parents and students to draw a balance between aspirations/expectation and the

reality of the occupational world. High prestige jobs are limited and so it is impossible for all students to attain them. Realitytesting and compromise are often involved in the educational and career implementation process and students and parents need

to learn the strategy of prioritizing their choices as well as to cope with uncertainties and maintain optimism. Meaning

construction, subjective well-being, and spirituality could be emphasized as an alternative to material fulllment and social

prestige in career choice and development.

This study suffered from several limitations. The rst limitation of this study is that only one of the parents responded to the

questionnaire. The maternal and paternal expectations for boys and girls might be different, and might have different effects on

the career aspirations of children. The second limitation is that we did not include a measure of students' career decision-making

and status, and thus we could not infer from the ndings whether a larger expectationaspiration gap might result in negative

decision-making status. The third limitation is that the participants came from the capital city which has more alternatives for

students, and family structure has high homogeneity, the results might not apply to smaller Chinese cities and rural areas (e.g.,

western part of China).

We hope that further conceptual formulations and empirical undertakings could be conducted in China and internationally to

shed light on how parental expectations could shape and nurture the aspirations of children. Future studies on the positive and

negative effects of parental expectations should continue to include parental and their children's perspective in the research

design. Researchers should include diverse variables, such as career choice status and difculties, parenting style, cultural-value

orientation, and academic achievement. Studies should also examine parents and students from diverse regions in China

representing different levels of economic modernization, exposure to Western cultural values, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

In conclusion, this study provides important ndings on the vocational expectations of parents as well as the corresponding

aspirations of their children. This is a unique study as no research study has yielded such information empirically. Although some

aspects of this study are indigenous in a Chinese cultural context, the conceptual essence of this study (e.g., career expectations

and aspirations, Gottfredson's theory) is well connected to the international literature. The ndings echoed those identied in the

international literature, such as the salience of parental expectations in the form of acceptable ranges, gender differences on

children's aspirations and parental expectations, and the effects of school types and parental educational background. The ndings

and their implications yield useful information for educational and counseling professionals in China and beyond.

References

Bratcher, W. E. (1982). The inuence of the family on career selection: A family systems perspective. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 61, 8791.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chao, R. K., & Sue, S. (1996). Chinese parental inuence and their children's school success: A paradox in the literature on parenting styles. In S. Lau (Ed.), Growing

up the Chinese way: Chinese child and adolescent development (pp. 93120). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Conklin, M. E., & Dailey, A. R. (1981). Does consistency of parental educational encouragement matter for secondary students? Sociology of Education, 54, 254262.

Creed, P. A., Conlon, E. G., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Career barriers and reading ability as correlates of career aspirations and expectations of parents and

their children. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 242258.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations [Monograph]. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28,

545579.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1996). Gottfredson's theory of circumscription and compromise. In D. Brown, L. Brook, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development

(pp. 179232). (3rd). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2002). Gottfredson's theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation. In D. Brown & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development

(pp. 85148). (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hannah, J. S., & Kahn, S. E. (1989). The relationship of socioeconomic status and gender to the occupational choices of Grade 12 students. Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 34, 161178.

Heckhausen, J., & Tomasik, M. J. (2002). Get an apprenticeship before school is out: How German adolescents adjust vocational aspirations when getting close to

developmental deadline. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 199219.

Helwig, A. A. (1998). Occupational aspirations of a longitudinal sample from second to sixth grade. Journal of Career Development, 24, 247267.

Henderson, S., Hesketh, B., & Tufn, K. (1988). A test of Gottfredson's theory of circumscription. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32, 3748.

Holland, J. L. (1985). Manual for the vocational preference inventory. FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1994a). Self-Directed Search: SDS Form R (4th ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1994b). The occupations nder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hwang, M. H., Kim, J. H., Ryu, J. Y., & Heppner, M. J. (2006). The circumscription process of career aspirations in South Korean adolescents. Asia Pacic Education

Review, 7, 133143.

Isaacson, L. E., & Brown, D. (2000). Career information, career counseling, and career development (7th ed.). MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Johnson, M. K., & Mortimer, J. T. (2002). Career choice and development from a sociological perspective. In D. Brown, & Associate (Eds.), Career choice and

development (pp. 3781). (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leong, F. T. L., & Seraca, F. C. (1995). Career development of Asian Americans: A research area in need of a good theory. In F. T. L. Leong (Ed.), Career development

and vocational behavior of racial and ethnic minorities (pp. 67102). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Leung, S. A. (1993). Circumscription and compromise: A replication with Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 40, 188193.

Leung, S. A., & Chen, P. H. (2009). Counseling psychology in Chinese communities in Asia: Indigenous, multicultural, and cross-cultural considerations. The

Counseling Psychologist, 37, 944966.

Leung, S. A., Conoley, C. W., & Scheel, M. J. (1994). The career and educational aspirations of gifted high school students: A retrospective study. Journal of Counseling

and Development, 72, 298303.

Leung, S. A., & Harmon, L. W. (1990). Individual and sex differences in the zone of acceptable alternatives. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37, 153159.

Leung, S. A., & Hou, Z. (2001). Concurrent validity of the 1994 Self-Directed Search for Chinese high school students in Hong Kong. Journal of Career Assessment, 9,

283296.

Leung, S. A., Hou, Z., Gati, & Li, X. (2011). Effects of parental expectations and cultural-values orientation on career decision-making difculties of Chinese

university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78, 1120.

Leung, S. A., Ivey, D., & Suzuki, L. (1994). Factors affecting the career aspirations of Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72, 404410.

Li, C. T., & Kerpelman, J. (2007). Parental inuences on young women's certainty about their career aspirations. Sex Roles, 56(12), 105115.

Marjoribanks, K. (2002). Family background, individual and environmental inuences on adolescents' aspirations. Educational Studies, 28, 3346.

360

Z. Hou, S.A. Leung / Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2011) 349360

Massey, E. K., Gebhardt, W. A., & Garnefski, N. (2008). Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Developmental Review,

28, 421460.

Mau, W. C. (1995). Educational planning and academic achievement of middle school students: A racial and cultural comparison. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 73, 518526.

Mau, W. C. (2003). Factors that inuence persistence in science and engineering career aspirations. The Career Development Quarterly, 51, 234243.

Mau, W. C., & Bikos, L. H. (2000). Educational and vocational aspirations of minority and female students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 78, 186194.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). NY: McGraw-Hill.

Otto, L. (1996). Helping your child choose a career. IN: JIST Works, Inc..

Otto, L. (2000). Youth perspectives on parental career inuence. Journal of Career Development., 27, 111118.

Rojewski, J. W. (2005). Career aspirations: Constructs, meaning, and application. In S. D. Brown & R.W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting

theory and research to work (pp. 131154). New York: Wiley.

Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2002). Teenage Aspirations for future careers and occupational outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 262268.

Sebald, H. (1986). Adolescents' shifting orientation toward parents and peers: A curvilinear trend over recent decades. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48, 513.

Shinar, E. H. (1975). Sexual stereotypes of occupations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 7, 99111.

Stephens, G., & Featherman, D. L. (1981). A revised socioeconomic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 10, 364395.

Tucker, C. J., Barber, B. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2001). Advice about life plans from mothers, fathers, and siblings in always-married and divorced families during late

adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 729747.

Vondracek, F. W., Lerner, R. M., & Schulenberg, J. E. (1986). Career development: A life-span developmental approach. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Whiston, S. C., & Keller, B. K. (2004). The inuences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 32, 493568.

Wilson, P. M., & Wilson, R. J. (1992). Environmental inuences on adolescent educational aspirations. Youth and Society, 24, 5270.

Young, R. A., Friesen, J. D., & Dillabough, J. M. (1991). Personal constructions parental inuence related to career development. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 25,

183190.

Youniss, J. (1986). Parentadolescent relationships. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development today and tomorrow (pp. 379392). : Jossey-Bass Inc.

Zhang, W., Hu, X. L., & Pope, M. (2002). The evolution of careers guidance and counseling in the People's Republic of China. Career Development Quarterly, 50,

226236.

You might also like

- Chapter 2Document6 pagesChapter 2Frustrated LearnerNo ratings yet

- Published by Canadian Center of Science and EducationDocument5 pagesPublished by Canadian Center of Science and EducationVhic EstefaniNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Parenting Styles and Academic PerformanceDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Parenting Styles and Academic Performanceea7y3197100% (1)

- Parental Involvement On AcademicsDocument7 pagesParental Involvement On AcademicsAgatha GraceNo ratings yet

- RRL LastDocument3 pagesRRL LastSharryne Pador ManabatNo ratings yet

- How Are Parental Expectations Related To Students' Beliefs and Their Perceived Achievement?Document22 pagesHow Are Parental Expectations Related To Students' Beliefs and Their Perceived Achievement?John Lorenz Cabalonga MalateNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Perceived Chinese Overparenting Scale in Emerging Adults in Hong KongDocument16 pagesValidation of The Perceived Chinese Overparenting Scale in Emerging Adults in Hong KongNeha JhingonNo ratings yet

- Parenting Teenagers As They Grow Up Values, Practices and Young People's Pathways Beyond School in EnglandDocument29 pagesParenting Teenagers As They Grow Up Values, Practices and Young People's Pathways Beyond School in EnglandAnindya Dwi CahyaNo ratings yet

- Psikopend - Does School Matter For Students' Self-Esteem - Associations of Family SES Peer SES and School Resources With Chinese Students Self-EsteemDocument9 pagesPsikopend - Does School Matter For Students' Self-Esteem - Associations of Family SES Peer SES and School Resources With Chinese Students Self-EsteemMaria SutarjaNo ratings yet

- Murayama 2015Document14 pagesMurayama 2015jjcostaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document11 pagesChapter 2Elyssa ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Fan, 2014 PDFDocument18 pagesFan, 2014 PDFMarco Adrian Criollo ArmijosNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Different Parenting Styles of Students' Academic Performance in Online Class SettingDocument29 pagesThe Effects of Different Parenting Styles of Students' Academic Performance in Online Class SettingSnowNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document6 pagesChapter 2Ella DavidNo ratings yet

- RRL VaronDocument8 pagesRRL Varon史朗EzequielNo ratings yet

- School and Work: Connections Made by South African and Australian Primary School ChildrenDocument13 pagesSchool and Work: Connections Made by South African and Australian Primary School Childrensoryna2709No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 FinalDocument9 pagesChapter 2 FinalRonnie Noble100% (1)

- Bruce-Koteyc Etr521 Finalproject PaperDocument16 pagesBruce-Koteyc Etr521 Finalproject Paperapi-435312842No ratings yet

- Adela POL321Document11 pagesAdela POL321igbinore sylvesterNo ratings yet

- N.R Parent 2 (Latest)Document15 pagesN.R Parent 2 (Latest)Aira FrancescaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument40 pagesResearchDexter RubionNo ratings yet

- R PDFDocument6 pagesR PDFWong Tiong LeeNo ratings yet

- Parental Role in Relation To Students' CognitiveDocument23 pagesParental Role in Relation To Students' CognitiveJanna Alyssa JacobNo ratings yet

- Journal of Vocational BehaviorDocument8 pagesJournal of Vocational BehaviorPostolache CatalinaNo ratings yet

- Family Environment Factors Linked to Perfectionist Types Among Hong Kong AdolescentsDocument7 pagesFamily Environment Factors Linked to Perfectionist Types Among Hong Kong AdolescentsflixrtNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument2 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesNoldlin Dimaculangan73% (79)

- Family, School, and Community Correlates of Children 'S Subjective Well-Being: An International Comparative StudyDocument25 pagesFamily, School, and Community Correlates of Children 'S Subjective Well-Being: An International Comparative Studyma_rielaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document5 pagesChapter 6Aeron Rai Roque100% (5)

- Relationship Between Parenting Styles, Academic Performance and Socio-Demographic Factors Among Undergraduates at Universiti Putra MalaysiaDocument15 pagesRelationship Between Parenting Styles, Academic Performance and Socio-Demographic Factors Among Undergraduates at Universiti Putra MalaysiaJamaica Duay BalmoriNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter 2Document34 pages09 Chapter 2Hanamitchi SakuragiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Single ParentDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Single Parentgvzftaam100% (1)

- Research Paper Parenting in USTDocument20 pagesResearch Paper Parenting in USTAntonio ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Final PaperDocument33 pagesGroup 5 Final PaperLendsikim TarrielaNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Student RetentionDocument4 pagesFactors Influencing Student RetentionIxiar Orilla Del Rìo100% (1)

- "It's For Your Future." The Implications of Asian Children and Forced Studies and ExcellenceDocument16 pages"It's For Your Future." The Implications of Asian Children and Forced Studies and ExcellenceAlyssa Marie GabuteroNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Wei, H.-S., Chen, J.-K. ENGDocument16 pages2010 - Wei, H.-S., Chen, J.-K. ENGFernando CedroNo ratings yet

- Related StudiesDocument11 pagesRelated Studiesimmanuel AciertoNo ratings yet

- 25-Article Text-69-1-10-20210322Document13 pages25-Article Text-69-1-10-20210322cxk jjhNo ratings yet

- Cultural Impact of Parental Expectations on Students' Academic StressDocument13 pagesCultural Impact of Parental Expectations on Students' Academic StressPearl Andrea VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Secondary School StudentsDocument20 pagesA Review of The Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Secondary School Studentsxpuraw21No ratings yet

- A Study On Relationship Between Personality Traits and Employment Factors of College StudentsDocument9 pagesA Study On Relationship Between Personality Traits and Employment Factors of College StudentsAnonymous kGnJ49SBlNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0883035520317948 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0883035520317948 MainSaqib saeedNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH TITLE: Investigating The Association of Students Multiple Intelligence, Relationship Skills, and SelfDocument4 pagesRESEARCH TITLE: Investigating The Association of Students Multiple Intelligence, Relationship Skills, and Selfmajorie allonesNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3745136Document6 pagesSSRN Id3745136KNo ratings yet

- How Mothers and Fathers Influence Academic AchievementDocument5 pagesHow Mothers and Fathers Influence Academic AchievementMoises MartinezNo ratings yet

- JPSP 2022 010Document10 pagesJPSP 2022 010Rhianne AngelesNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature: (Chapter 2) - 1Document5 pagesReview of Related Literature: (Chapter 2) - 1Julienne AquinoNo ratings yet

- Adolescents Emerging Habitus The Role of Early Parental Expectations and PracticesDocument25 pagesAdolescents Emerging Habitus The Role of Early Parental Expectations and PracticesLeonardo Ariza RuizNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Authoritarian Parenting Style and Academic Performance in School Students Khalida Rauf Junaid AhmedDocument11 pagesThe Relationship of Authoritarian Parenting Style and Academic Performance in School Students Khalida Rauf Junaid Ahmedchloe liaoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Page 1Document32 pagesChapter 1 Page 1nawazishNo ratings yet

- Parental PressureDocument50 pagesParental PressureMary Vettanny Pastor74% (19)

- Family Factors Affect Behavioral LearningDocument11 pagesFamily Factors Affect Behavioral Learningjasmin grace tanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Students' Academic PerformanceDocument40 pagesFactors Affecting Students' Academic PerformanceToheeb AlarapeNo ratings yet

- Brooks HighSchoolExperiences v.01Document19 pagesBrooks HighSchoolExperiences v.01Vaida Andrei OrnamentNo ratings yet