Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stiggins Interview On Assessment

Uploaded by

scmsliteracy0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

181 views3 pagesRick stiggins: we must clearly articulate the achievement targets we want students to hit. "We cannot accurately assess that which we don't understand," he says. Only a handful of states require competency in assessment as a condition of licensure.

Original Description:

Original Title

Stiggins Interview on Assessment

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRick stiggins: we must clearly articulate the achievement targets we want students to hit. "We cannot accurately assess that which we don't understand," he says. Only a handful of states require competency in assessment as a condition of licensure.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

181 views3 pagesStiggins Interview On Assessment

Uploaded by

scmsliteracyRick stiggins: we must clearly articulate the achievement targets we want students to hit. "We cannot accurately assess that which we don't understand," he says. Only a handful of states require competency in assessment as a condition of licensure.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

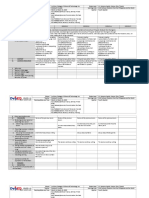

You are on page 1of 3

Assessment without victims:

An Interview with Rick Stiggins

JSD: Teachers and principals are interested in showing that the new instructional practices being

used in their classrooms are improving student learning. But they’re often impatient about

waiting for next year's standardized test results to come back. How can improved formative

classroom assessment help in this situation?

Stiggins: Two things are important here. The first is that we must clearly articulate the

achievement targets we want students to hit. If there's knowledge to be mastered, what

knowledge? What are the reasoning proficiencies, performance skills, or product development

capabilities we want?

It's important that all teachers be confident, competent masters of the targets that their students

are shooting for. Unfortunately, however, as I travel the country I find teachers who are

responsible for teaching writing or reading, for example, but who don't have the slightest idea

what good writing looks like or what makes a good reader. That's because they haven't been

given the opportunity from a professional development point of view to master those

achievement targets themselves. It's not a pervasive problem, but it's big enough to mention in

this context. This mastery is the foundation for quality assessment. We cannot accurately assess

that which we don't understand.

The second thing is that teachers need to know how to transform these valued achievement

targets into quality, day-to-day classroom indicators of achievement. That's the foundation of

assessment literacy. Teachers who know how to do this can document student achievement day

to day in their classrooms and watch the progression of student learning. And, if someone asks,

they can provide compelling evidence of things their students can now do that they couldn't do

before.

Assessment literacy for teachers

JSD: How well prepared are teachers to use the skills you've just described?

Stiggins: Generally, they're not very well prepared. Only a handful of states require competency

in assessment as a condition of licensure. Even more troubling is that only three states require

competence in assessment for principal certification. The vast majority of practicing teachers and

administrators have not had the opportunity to develop the assessment literacy they need.

Because the typical teacher can spend a third to a half of his or her professional time in

assessment-related activities, teachers need inservice opportunities to learn assessment strategies.

From a staff development point of view, it's important that all teachers understand which

assessment methods to use in what situations. For example, while it's not trendy to talk in these

terms, multiple choice tests still have a contribution to make for certain achievement targets and

in certain contexts. Under other circumstances, essays or performance assessments might be the

best choice. The trick is to know which method to use when and how to use it well. That's

assessment literacy.

Fit the assessment to the goal

JSD: What are some examples of classroom-friendly ways that teachers can use to assess student

learning on an ongoing basis that would demonstrate to them and to others whether students are

learning more because new practices are being tried in their classrooms?

Stiggins: In the area of elementary reading, teachers can use techniques like running records in

which they keep track of students' fluency and comprehension. Oral retelling of stories by young

students can be used to check their understanding. Simply asking students one-on-one or through

a group process to talk about what they read can let us know if they comprehend it.

For writing, it's important that the curriculum be spelled out in terms of stages of writing

development. What it takes to be a competent emergent writer is different from what it takes to

be a competent intermediate writer or a high school writer. From a writing proficiency point of

view, the best of all assessment methods is to have kids write and to have others evaluate the

products they create. Analytic writing rubrics are useful here; there are a number of them around

the country that I think are really focused and powerful. At the Assessment Training Institute, we

believe it’s essential to share standards with students up front and teach them to evaluate their

own and each other's writing.

To assess reasoning, problem solving, and critical thinking, we need to define what specific

patterns of thinking we want students to demonstrate. This will play out differently, though, in

different academic disciplines. In science, for example, certain patterns of inferential reasoning

characterize the scientific method. Here teachers can pose specific science problems and ask

students to demonstrate that they can reason in a scientific way.

Students learn from assessments

JSD: A study in England found that many of the most successful instructional innovations used

student self-assessments and peer assessments to strengthen formative assessment in the

classroom. The study also found that improved formative assessment raised student achievement

overall but that it helped low achievers most.

Stiggins: I, too, have read that very important research. The key is to understand the relationship

between assessment and student motivation. In the past, we built assessment systems to help us

dole out rewards and punishment. And while that can work sometimes, it causes a lot of students

to see themselves as failures. If that goes on long enough, they lose confidence and stop trying.

When students are involved in the assessment process, though, they can come to see themselves

as competent learners. We need to involve students by making the targets clear to them and

having them help design assessments that reflect those targets. Then we involve them again in

the process of keeping track over time of their learning so they can watch themselves improving.

That's where motivation comes from.

We can also involve students in communicating what they learned, for example, through student-

led conferences, which is probably one of the biggest breakthroughs in communicating about

student achievement in the last century. Grant Wiggins says he wants classrooms in which there

are no surprises and no excuses. Involve students deeply in the assessment process and that's

what you get.

Kids who have given up on learning are at the low end. If we can involve them in the assessment

process to give them renewed confidence and motivation, they're likely to try harder and to

succeed. The kids who had previously given up on themselves have rekindled interest and get

renewed confidence when involved in high quality formative assessment.

Assessments motivate teachers

JSD: Let's talk about teacher motivation. Teachers today are being asked to significantly change

their practice and sustain that over time. Teachers wonder if the new things they’re doing really

makes a difference with students. And it's hard to sustain new practices unless you know they’re

making a difference for students. So it seems that the formative process of assessment would not

only benefit students in the ways you've just described, but help with teacher motivation as well.

Stiggins: I have a strong faith in teachers. They are for the most part in this profession because

they care about kids. I believe that if, on a day-to-day basis, they accurately assess whether kids

are becoming good readers, writers, and math problem solvers and if those teachers are using

classroom assessment smartly, then the once-a-year test scores will take care of themselves.

Good formative assessment processes gives teachers evidence that students are progressing, and

that’s what will keep them going. Formative assessment gives teachers confidence that they’re

getting better and better. Students and teachers feel in control. They don't feel victimized. The

assessment environment we have in the United States today is one in which everyone feels

victimized. And that's got to change.

I dream of the day when state assessments intimidate no one because going into the test everyone

knows what the results will be. Such high-stakes tests should just corroborate everything that

teachers already know about kids because the classroom assessment process has told them

everything they need to know.

Model new practices

JSD: What are the implications of all of this for staff development?

Stiggins: Teachers are not being given the tools they need to help students succeed, and

classroom assessment tools are at the head of the list of what teachers need. We have to allocate

staff development resources to help teachers in this area.

It's important to model in staff development the kind of classroom learning environments and the

internal sense of control that we'd like to have teachers develop for students. If we place a

premium in the classroom on students taking a lead in their own learning, we need to model that

same thing in professional development. In the area of assessment, teachers need the opportunity

to manage their own development and to monitor their increasing competence in classroom

assessment and its impact on kids. If teachers experience that kind of responsibility, they’re more

likely to transfer their professional learning into practices that help kids develop those same

qualities.

Adults and students can hit any target they can see and that holds still for them. If teachers can

see the key characteristics of an assessment-literate educator, they can monitor how they are

progressing toward them. Once they get there, they can look back and say, "That's where I was

and here's where I am now. And who's responsible for that? I am."

Teachers must experience in their professional learning the same type of formative assessment

processes we'd like them to use with kids, such as building a portfolio of their increasing

classroom assessment competence and confidence. Teachers are then responsible for telling the

story of their own learning, and there's a sense of efficacy that comes from that.

You might also like

- Restaurants Ready To Hire, But Welfare Keeps Workers Home: in The NewsDocument52 pagesRestaurants Ready To Hire, But Welfare Keeps Workers Home: in The NewsKeithStewartNo ratings yet

- Hodson, Geoffrey - Human Happiness (Art)Document3 pagesHodson, Geoffrey - Human Happiness (Art)XangotNo ratings yet

- Plain Truth 1955 (Vol XX No 05) Jun - WDocument16 pagesPlain Truth 1955 (Vol XX No 05) Jun - WTheTruthRestoredNo ratings yet

- I Am Sharing 'Lesson-1-Introduction-To-Mythology' With You - 221108 - 132446Document5 pagesI Am Sharing 'Lesson-1-Introduction-To-Mythology' With You - 221108 - 132446Mark James RoncalesNo ratings yet

- UnitedStates 20210528 EpochTimesDocument28 pagesUnitedStates 20210528 EpochTimesKeithStewartNo ratings yet

- Keystone Canceled, A Community Devastated: in The NewsDocument52 pagesKeystone Canceled, A Community Devastated: in The NewsKeithStewartNo ratings yet

- Plain Truth 1962 (Vol XXVII No 09) Sep - WDocument48 pagesPlain Truth 1962 (Vol XXVII No 09) Sep - WTheTruthRestoredNo ratings yet

- Wecdsb Aer 2011-2012Document68 pagesWecdsb Aer 2011-2012sadoneNo ratings yet

- 289 - Benjamin Fulford For October 29, 2012Document2 pages289 - Benjamin Fulford For October 29, 2012David E RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Lithuania Withdraws From China's 17+1' Cooperation PlatformDocument28 pagesLithuania Withdraws From China's 17+1' Cooperation PlatformKeithStewartNo ratings yet

- Plain Truth 1963 (Vol XXVIII No 09) Sep - WDocument52 pagesPlain Truth 1963 (Vol XXVIII No 09) Sep - WTheWorldTomorrowTVNo ratings yet

- Assessment ManifestoDocument4 pagesAssessment Manifestoapi-609730921No ratings yet

- Assessments Guide Effective TeachingDocument3 pagesAssessments Guide Effective Teachingjsjjsjs ksksndNo ratings yet

- Stiggins - Assessment Through The Students Eyes 2Document6 pagesStiggins - Assessment Through The Students Eyes 2Destiny RamosNo ratings yet

- Using Student-Involved Assessment PDFDocument7 pagesUsing Student-Involved Assessment PDFJeffrey BeltranNo ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment For Learning ChappuisDocument5 pagesClassroom Assessment For Learning ChappuisRothinam NirmalaNo ratings yet

- Principles of High Quality Assessment in the ClassroomDocument5 pagesPrinciples of High Quality Assessment in the ClassroomHarry ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Comments - Personal Philosophy On AssessmentsDocument8 pagesPedagogical Comments - Personal Philosophy On Assessmentsapi-238559203No ratings yet

- Assessment For LearningDocument6 pagesAssessment For Learningapi-300759812No ratings yet

- Importance of Affective Assessments: Item Writing GuidelinesDocument11 pagesImportance of Affective Assessments: Item Writing GuidelinesMariaceZette RapaconNo ratings yet

- Journal For Philoposhy of AssessmentDocument6 pagesJournal For Philoposhy of Assessmentapi-395977210No ratings yet

- Student Feedback Key to Course ImprovementDocument4 pagesStudent Feedback Key to Course ImprovementMahnoor ParachaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Assessment FinalDocument8 pagesPhilosophy of Assessment Finalapi-282665349No ratings yet

- Assessment Strategies That Can Increase MotivationDocument3 pagesAssessment Strategies That Can Increase MotivationClaren dale100% (15)

- Philosophy of AssessmentDocument3 pagesPhilosophy of Assessmentapi-332198325No ratings yet

- 6 Types of Assessments to Use in Your ClassroomDocument15 pages6 Types of Assessments to Use in Your ClassroomAsia SultanNo ratings yet

- Assessment Practices Among Malaysian Cluster School TeachersDocument4 pagesAssessment Practices Among Malaysian Cluster School Teachersapi-304082003No ratings yet

- Assessment Philosophy - FinalDocument5 pagesAssessment Philosophy - Finalapi-332187763No ratings yet

- 8602 Solved ETADocument9 pages8602 Solved ETASana IjazNo ratings yet

- Importance of AssessmentDocument3 pagesImportance of AssessmentTizieNo ratings yet

- Using Student Involved Classroom Assessment To Close Achievement GapsDocument4 pagesUsing Student Involved Classroom Assessment To Close Achievement Gapsapi-628146149No ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment For Student Learning - The MAIN IDEADocument11 pagesClassroom Assessment For Student Learning - The MAIN IDEAMyers RicaldeNo ratings yet

- BEST READING PracticesDocument1 pageBEST READING Practicesfritzie marie lagguiNo ratings yet

- Activities/Assessment:: Lea Fe Comilang ArcillaDocument9 pagesActivities/Assessment:: Lea Fe Comilang ArcillaRhem Rick Corpuz100% (11)

- PRQ Paper 4Document6 pagesPRQ Paper 4api-317362905No ratings yet

- Formative and Summative Assessment Strategies in Distance LearningDocument6 pagesFormative and Summative Assessment Strategies in Distance LearningMary Joy FrondozaNo ratings yet

- Suervision and InstructionDocument5 pagesSuervision and InstructionAiza N. GonitoNo ratings yet

- Human Resource DevelopmentDocument3 pagesHuman Resource DevelopmentDavaaNo ratings yet

- Parera Clay Assignmentfirstfinal2Document11 pagesParera Clay Assignmentfirstfinal2api-327883311No ratings yet

- Why We Use Test?: T o Identify What Students Have LearnedDocument3 pagesWhy We Use Test?: T o Identify What Students Have LearnedPrecious Pearl100% (1)

- Module 25 No 2Document5 pagesModule 25 No 2jhonrainielnograles52No ratings yet

- Effective Teacher SkillsDocument29 pagesEffective Teacher SkillsziapsychoologyNo ratings yet

- Types of Assessment GuideDocument15 pagesTypes of Assessment GuideCristina SalenNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of a Good Test ReflectionDocument8 pagesCharacteristics of a Good Test ReflectionAngelica BautistaNo ratings yet

- Educhapter 12 ForportfolioDocument2 pagesEduchapter 12 Forportfolioapi-315713059No ratings yet

- Predicting Academic Success in Higher Education: What's More Important Than Being Smart?Document4 pagesPredicting Academic Success in Higher Education: What's More Important Than Being Smart?via_djNo ratings yet

- Assessment FinalDocument6 pagesAssessment Finalapi-285680972No ratings yet

- Joan N. Agao: Explore Activity 1: Concept ClarificationDocument3 pagesJoan N. Agao: Explore Activity 1: Concept ClarificationJoan N. Agao80% (5)

- VPC VP VP: PPPP PPP PP PPPPPPPPDocument6 pagesVPC VP VP: PPPP PPP PP PPPPPPPPyibie19852467No ratings yet

- Assessment Philosophy Final DraftDocument4 pagesAssessment Philosophy Final Draftapi-308357583No ratings yet

- Amandanewcomb Prq4finalDocument5 pagesAmandanewcomb Prq4finalapi-352269670No ratings yet

- Common Interview Questions For Primary TeachersDocument6 pagesCommon Interview Questions For Primary TeachersBhavesh KNo ratings yet

- Assessment Philosophy StatementDocument6 pagesAssessment Philosophy Statementapi-336570695No ratings yet

- Types of Classroom AssessmentDocument10 pagesTypes of Classroom AssessmentJenica BunyiNo ratings yet

- What Does Research Say About AssessmentDocument20 pagesWhat Does Research Say About AssessmentalmagloNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On School SupervisionDocument5 pagesTerm Paper On School Supervisionc5praq5p100% (1)

- Philosophy of Assessment WordDocument8 pagesPhilosophy of Assessment Wordapi-242399099No ratings yet

- PRQ 4Document6 pagesPRQ 4api-295760565No ratings yet

- Role of Teacher in Classroom AssessmentDocument5 pagesRole of Teacher in Classroom AssessmentTehmina HanifNo ratings yet

- Formative and Summative Assessment1Document22 pagesFormative and Summative Assessment1Sheejah SilorioNo ratings yet

- SCMS Basic Reading Intervention ChartDocument2 pagesSCMS Basic Reading Intervention ChartscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- KDEs On-Demand StuffDocument41 pagesKDEs On-Demand StuffscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Standards-Based Literary ResponseDocument2 pagesStandards-Based Literary ResponsescmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Before During After Strategy Chart EmptyDocument1 pageBefore During After Strategy Chart EmptyscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- CEI ExplanationDocument1 pageCEI ExplanationTeachThoughtNo ratings yet

- Reading Strategy Reader Purpose 5WsDocument1 pageReading Strategy Reader Purpose 5WsscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- SCMS Literacy Committee Meeting Minutes Jan 2009Document2 pagesSCMS Literacy Committee Meeting Minutes Jan 2009scmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- ELA Best PracticesDocument3 pagesELA Best Practicesscmsliteracy100% (1)

- Anticipation GuideDocument1 pageAnticipation GuidescmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Text Connections Text: Name: Period: Essential QuestionDocument3 pagesText Connections Text: Name: Period: Essential QuestionscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Writing Your Autobiography: Important Memorie Key EventsDocument4 pagesWriting Your Autobiography: Important Memorie Key EventsscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Prediction GuideDocument1 pagePrediction GuidescmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Get To The Root of ItDocument4 pagesGet To The Root of Itscmsliteracy0% (1)

- Mass ELA Releases ORQs Grade 8Document24 pagesMass ELA Releases ORQs Grade 8scmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Overview of Assessment (DuFour)Document2 pagesOverview of Assessment (DuFour)scmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Reading Strategies TableDocument4 pagesReading Strategies TablescmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Power Reading TriangleDocument1 pagePower Reading TrianglescmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Literacy Plan OverviewDocument1 pageLiteracy Plan OverviewscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Phonemic AwarenessDocument7 pagesPhonemic AwarenessscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Continuum of AssessmentDocument1 pageContinuum of AssessmentscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Fix The Clunk Reading StrategiesDocument1 pageFix The Clunk Reading StrategiesscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Princeton Review Formative Assessment PitchDocument12 pagesPrinceton Review Formative Assessment PitchscmsliteracyNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Final Oral DefenseDocument54 pagesCriteria For Final Oral DefenseJohn Venheart AlejoNo ratings yet

- Collaborating For Success With The Common Core A T... - (References and Resources)Document6 pagesCollaborating For Success With The Common Core A T... - (References and Resources)Nguyen Thi Hong HanhNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesLesson PlanAILENE LIM100% (2)

- Moon Facts Lesson Plan-First Observed LessonDocument3 pagesMoon Facts Lesson Plan-First Observed Lessonapi-507784209No ratings yet

- R Donnelly Critical Thinking and Problem SolvingDocument116 pagesR Donnelly Critical Thinking and Problem SolvingBalaji Mahesh Krishnan67% (3)

- Assessment Task 5Document4 pagesAssessment Task 5Rafaela Mabayao92% (12)

- Ebr He VanesDocument5 pagesEbr He VanesKuro HanabusaNo ratings yet

- RRB NTPC Previous Year Exam Papers e Book 2012 2016 PDFDocument47 pagesRRB NTPC Previous Year Exam Papers e Book 2012 2016 PDFImam Gajula100% (1)

- PT3 Science DSKP + KSSM Notes - Exam Tips UPSR PT3 SPM 2019 - 2020Document4 pagesPT3 Science DSKP + KSSM Notes - Exam Tips UPSR PT3 SPM 2019 - 2020anon_4133945530% (1)

- Monthly Supervisory and Itinerary APRIL 2024Document58 pagesMonthly Supervisory and Itinerary APRIL 2024david john uberaNo ratings yet

- Shampoo Dough Lesson PlanDocument1 pageShampoo Dough Lesson Plandmfitch78No ratings yet

- The Useof Mother Tonguein Teaching Elementary MathematicsDocument11 pagesThe Useof Mother Tonguein Teaching Elementary MathematicsNicsy xxiNo ratings yet

- Block-II Block-I Block-II Block-II Block-I Block-II: PR: MATH 2014Document2 pagesBlock-II Block-I Block-II Block-II Block-I Block-II: PR: MATH 2014Alolan EricNo ratings yet

- Mnemonic TechniquesDocument11 pagesMnemonic TechniquesmonserrathNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Activities & Skills: Cce / Ee ICT SkillsDocument5 pages21st Century Activities & Skills: Cce / Ee ICT SkillsHazimah AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Course SyllabusDocument11 pagesCourse SyllabusGlicerio Peñueco Jr.No ratings yet

- Multigrade Classroom Books1 7Document376 pagesMultigrade Classroom Books1 7Mark neil a. GalutNo ratings yet

- Charter ActsDocument4 pagesCharter ActsUmair Mehmood100% (1)

- Humair Shah New CVDocument2 pagesHumair Shah New CVSyed HumairNo ratings yet

- Curr. Map Oral Comm.Document4 pagesCurr. Map Oral Comm.CEEJAY PORGATORIONo ratings yet

- Profiling Professional EFL Teachers SeminarDocument3 pagesProfiling Professional EFL Teachers SeminarGilang Giandi100% (1)

- Success Is Inevitable - Action GuideDocument58 pagesSuccess Is Inevitable - Action Guidemoonlover31100% (1)

- Millicent Atkins School of Education: Common Lesson Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesMillicent Atkins School of Education: Common Lesson Plan Templateapi-505035881No ratings yet

- The Demands of Society From The Teacher As ProfessionalDocument26 pagesThe Demands of Society From The Teacher As ProfessionalFranklin CuisonNo ratings yet

- TattlingDocument4 pagesTattlingapi-404448001No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ReflectionDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Reflectionapi-508424314No ratings yet

- CHCECE046 Self-Study GuideDocument4 pagesCHCECE046 Self-Study GuideRekhaNo ratings yet

- Jessica Tingley Resume 2Document2 pagesJessica Tingley Resume 2api-399468103No ratings yet

- Sos Bagramyan: Curriculum VitaeDocument4 pagesSos Bagramyan: Curriculum Vitaeapi-419659777No ratings yet

- 21st CenturyDocument3 pages21st CenturyShendy AcostaNo ratings yet