Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Careful Management. The Borghese Family and Their Fiefs in Early Modern Lazio

Uploaded by

Albert LanceOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Careful Management. The Borghese Family and Their Fiefs in Early Modern Lazio

Uploaded by

Albert LanceCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

www.brill.nl/jemh

A Careful Management: The Borghese Family

and their Fiefs in Early Modern Lazio*

Bertrand Forclaz

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Abstract

This article investigates economic management of efs as well as social relationships between

lords and vassals in 17th- and 18th-century central Italy. Up to recent years, historians of

early modern Italy as well as other European countries have stressed the archaic features

of noble management, which would have prevented the emergence of a modern marketoriented agrarian economy, or have portrayed noblemen as market-oriented landowners

neglecting their seigneurial rights. I argue here that both dimensions were present in noble

management, as lords did not choose between them, but rather leaned upon one or the

other according to circumstances. I base my argument on the case of the Borghese, one of

the wealthiest papal families of the 17th century. Finally, this study shows that modern elements could be brought into a model characterized by strong seigneurial rights.

Keywords

Fiefdom, Southern Italy, seigneurial rights, Borghese

Introduction

Seigneurial rights played a key role in the economic and social life of several rural areas in early modern Europe, including Southern Italy. The

emergence of a new nobility, the regulation of the market for efs by public

magistracies, and changes in their management even led to a strengthening

* This article sums up part of my PhD Thesis, discussed at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes

en Sciences Sociales (Paris) in 2003 : Les Borghese et leurs efs aux XVIIe et XVIIIe sicles.

Gestion conomique, stratgies sociales et enjeux politiques. It was presented at the European

Social Science History Conference in Berlin in March 2004; I would like to thank the

chair of the session, Jan Luyten van Zanden, and the participants for their comments, as

well as Bas van Bavel, Maarten Prak and Gregory Hanlon for their comments on previous

versions of the text; a special thanks to Gregory Hanlon for correcting the English.

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008

DOI: 10.1163/138537808X334331

170

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

of seigneurial rights, in which conicts between feudal lords and communities became more frequent. In the 1960s, historians of Southern Italy

argued about the nature of these transformations. Rosario Villari proposed

the concept of refeudalization in the second half of the 16th and rst half

of the 17th century, whereby relations between feudal lords and their

subjects hardened as the former exerted economic pressure on the latter,

due to the renewal of the aristocracy and the nancial power of the new

lords. Giuseppe Galasso objected that this thesis implied a preceding

defeudalization which was unlikely to have taken place. Over time, this

debate lost its polemical component, although new empirical research has

conrmed the hardening of seigneurial rights.1 The refeudalization thesis

stressed the archaic features of noble management, which would have

prevented the emergence of a modern market-oriented agrarian economy.

In his 1978 essay on the Italian transition from feudalism to capitalism,

Maurice Aymard, while stressing the modern elements in the management of Southern Italian latifundia, such as production for the market and

the constitution of large estates, explained those features by the transformation of feudal lords into mere landowners. Later contributions to the

study of noble management reinforced the antinomy by insisting on feudalisms traditional features and reasserting the importance of seigneurial

rights against market-oriented production in poorer areas.2

If we consider other historiographic traditions, we will nd a similar

opposition between traditional seigneurial rights and modern economic management, the former being seen as the dead weight of the past

hampering economic growth and modernization. This vision is linked to

the idea of a bourgeois revolution erupting in the 19th century. One exception to that framework would be England. Noble landlords there have

been described as the main protagonists of the agricultural revolution

which took place in the 18th century, via the enclosure and the creation of

large estates, although recent research has questioned this view and stressed

the active role of leaseholders.3 In France, the nobility has been identied

See R. Villari, La rivolta antispagnola a Napoli. Le origini (1585-1647) (Rome, 1967);

G. Galasso, Economia e societ nella Calabria del Cinquecento (Naples, 1967).

2

See M. Aymard, La transizione dal feudalesimo al capitalismo, in R. Romano,

C. Vivanti (eds.), Storia dItalia, Annali, I, Dal feudalesimo al capitalismo (Turin, 1978),

1131-192; T. Astarita, The Continuity of Feudal Power. The Caracciolo di Brienza in Spanish

Naples (Cambridge, 1992).

3

See R.C. Allen, Enclosure and the Yeoman: The Agricultural Development of the South

Midlands, 1450-1850 (Oxford, 1992).

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

171

as a source of agrarian backwardness, and the leaseholders of large noble

estates have been identied as the only element of modernization and

growth in a rural economy considered as conservative and stationary. Even

this model has been revised recently, as Philip Homan has pointed out

agents of growth within the local peasantry.4 Most recently, scholars have

tried to go beyond the opposition of feudalism to capitalism: while

acknowledging the importance of tradition in noble economic behaviour,

they have emphasized the concern of noblemen with prot and their care

for sound management. William Hagens book on Prussian Junkers showed

that heavy seigneurial rights did not preclude the efs from being protdriven enterprises, and that commercialized manorialism could generate

growth and enrichment.5

We thus need to get rid of an either/or alternative in which noblemen

are seen either as feudal lords who blocked any agricultural modernization

or as market-oriented landowners neglecting their seigneurial rights. In

this paper, I argue that both dimensions were likely present in noble management, as noblemen did not choose between them, but rather leaned

upon one or the other according to circumstances. The object of my

research is a papal family, the Borghese. I will explain the nature of their

authority and its impact on the economic life of the efs they owned in the

Papal States, and investigate their relationships with the inhabitants and

the transformation of these relationships over time.

The Borghese family belonged to the papal nobility.6 Marcantonio

Borghese came from Siena to Rome in the 1530s and worked as a lawyer

4

See P.T. Homan, Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 14501815, Princeton, 1996; concerning the nobility as a source of agrarian backwardness, see

J. Dewald, Pont-St-Pierre 1398-1789. Lordship, Comunity, and Capitalism in Early Modern

France (Berkeley, 1987), 285-86.

5

See W. W. Hagen, Ordinary Prussians. Brandenburg Junkers and Villagers, 1500-1800

(Cambridge, 2002); for this historiographical shift, see P. Janssens, B. Yun-Casalilla (eds.),

European Aristocracies and Colonial Elites. Patrimonial Management Strategies and Economic

Development, 15th-18th Centuries (Aldershot, 2005).

6

On the Borghese family, see W. Reinhard, mterlaufbahn und Familienstatus. Der

Aufstieg des Hauses Borghese 1537-1621, in Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen

Archiven und Bibliotheken, 54, 1974, 328-427; W. Reinhard, Papstnanz und Nepotismus

unter Paul V. (1605-1621). Studien und Quellen zur Struktur und zu quantitativen Aspekten

des ppstlichen Herrschaftssystems, 2 vols., Stuttgart, 1974; G. Pescosolido, Terra e nobilt.

I Borghese. Secoli XVIII e XIX (Rome, 1979); V. Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese

(1605-1633). Vermgen, Finanzen und sozialer Aufstieg eines Papstnepoten (Tbingen, 1984);

B. Forclaz, La famille Borghese et ses efs. Lautorit ngocie dans lEtat pontical dAncien

Rgime (Rome, 2006) (abridged and reviewed version of my PhD Thesis).

172

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

at the Roman Curia; he was able to develop important connections within

the Curiaand with the Roman nobility, for several of his children married

into patrician families. One of his sons, Camillo, embarked on an ecclesiastical career. Vice-auditor of the Apostolic Chamber from 1588 on, nuncio in Madrid in 1593, he was made cardinal in 1596 and was elected pope

in 1605, at the relatively young age of 53. He took the name of Paul V and

was to reign until 1621. This unexpected electionhe was a compromise

candidate between opposing factionsallowed his family to complete its

rapid social ascension into the high nobility. The mechanisms of this ascension are classic: Camillo appointed a cardinal-nephew, Scipione Borghese, as superintendent of the Papal States, entrusted with the care of the

familys clients. The Borghese multiplied their matrimonial alliances with

the old Roman nobility, such as the marriage between the popes nephew,

Marcantonio, and Camilla Orsini. They embraced a more aristocratic lifestyle, entailing the purchase of a suburban villa and enlarging the family

palace in Campomarzio. Not least, they acquired extensive real estate, both

feudal and allodial.

The case of the Borghese as lords is interesting for several reasons: did

their acquisition of efs lead to a strengthening of seigneurial rights during

the 17th century? Within the wide range of assets they held, which element proved more important, land ownership or seigneurial rights? The

answer to these questions might help us establish the particular place of

Lazio in early modern rural Italy. Was it a stronghold of seigneurial rights,

as in Southern Italy, or did nobles there adopt more modern forms of

landed property and management, as in Northern and Central Italy? Furthermore, the Borghese example can help us understand the management

style of noble landlords and their role in early modern rural economy.

Did they adopt management choices which were specic to new nobles

and which diered from those of the old nobility, as Volker Reinhardt has

suggested was the case for Paul Vs nephew, cardinal Scipione Borghese,

stressing his commercial acumen?7 Before we can answer those questions,

we need to show the importance of efs in the familys assets.

See Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

173

The Constitution of the Landed Patrimony

Thanks to the important donations by the pope, the family was able to buy

extensive domains in the Agro romano, the countryside around Rome,

together with efs across Lazio, the latter providing the Borghese with titles

of nobility. The purchase of these efs resulted from the debts of old noble

families, who were constrained to sell part of their estates from the second

half of the 16th century on.8 Papal authority proved central in these land

investments, for only the pope could authorize an entail to be broken.

Whereas the Apostolic Chamberthe institution managing the patrimony

of the Holy Seebought some of the estates brought onto the market, the

main purchasers were the popes relatives, who had privileged insider information. During his long ponticate, Paul V donated more than 3 million

scudi to his relatives, and several loans were made to them by the Apostolic

Chamber under favorable conditions.9 This policy was also followed by the

other popes of the 17th century, although from the late 1660s on, due to

nancial diculties of the Papal States, it became less routine. Such aggressive nepotism has been overlooked by the supporters of the thesis of a weakening of feudal nobility in the Papal State from the late 16th century on, in

the aftermath of pope Pius V prohibiting the infeudation of new lands in

1567. The practice of nepotism directly limited the relevance of this measure, since most popes sought to provide their relatives with efs sold by the

old nobility. Nepotism also limited the centralization of the Papal States

especially in the Lazio region, around Rome, where territories directly

depending on the Holy See were strewn with efs.10

See J. Delumeau, Vie conomique et sociale de Rome dans la seconde moiti du XVIe sicle,

vol. I (Paris, 1957-59), 459-485; F. Piola Caselli, Una montagna di debiti. I monti baronali dellaristocrazia romana nel Seicento, in Roma moderna e contemporanea, I, 1993, 2,

21-56; S. Raimondo, Il prestigio dei debiti. La struttura patrimoniale dei Colonna di

Paliano alla ne del XVI secolo (1596-1606), in Archivio della Societ Romana di Storia

Patria, 120, 1997, 65-165.

9

See Reinhard, Papstnanz und Nepotismus, vol. I, 119-138; Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese, 196-98, 209, 219-26.

10

Historians traditionally insisted on the eciency of centralization in the Papal State

and on the limits of seignorial powers: see mostly P. Prodi, Il sovrano pontece. Un corpo e

due anime : la monarchia papale nella prima et moderna (Bologna, 1982); B.G. Zenobi,

Le ben regolate citt: modelli politici nel governo delle periferie ponticie in et moderna

(Rome, 1992). Recent scholarship, however, has considerably undermined this thesis: see

lately M.A. Visceglia (ed.), La nobilt romana in et moderna. Proli istituzionali e pratiche

sociali, Rome, 2001 ; C. Castiglione, Patrons and Adversaries. Nobles and Villagers in Italian

Politics, 1640-1760 (Oxford, 2005); Forclaz, La famille Borghese et ses efs.

8

174

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

Thanks to Paul Vs long papacy and the donations deriving from it, the

Borghese became one of the biggest landowners in Rome: between 1607

and 1621, Paul Vs brothers, Francesco and Giovan Battista, and his

nephew, cardinal Scipione, bought 12 efs scattered around the Eternal

City. The most prestigious efs were situated in Southern Lazio and had

belonged to old families: the Colonna, the Caetani and the Savelli. Scipione and his uncles did not adopt a territorial strategy but rather exploited

every protable occasion, purchasing efs in Northern Lazio and in Sabina,

to the north-east of Rome. In addition to feudal jurisdictions, they also

bought allodial properties in the Agro romano, the deserted Roman countryside, whose nancial return was a bit higher than that of efs (3,75-4%

against 2,5-3% of the value of the estate). They invested about 1,2 million

scudi in efs and 1,3 million in these allodial properties.11

Two features characterize the Borghese familys landed investments relative to other papal families of the 17th century: the importance of allodial

properties in their patrimonyin the middle of the century, they were the

second largest holder of such lands in the Agro romano, after the Chapter

of St. Peterand the continuation of their expansion after Paul Vs death.

Between 1621 and the late 1670s, the Borghese bought 19 more efs, so

that they owned 31 of them at the beginning of the 18th century, with a

total of 24 000 inhabitants. Only the Colonna, one of the oldest families

in the Roman nobility, had more subjects (31,000). The Borghese could

not buy any more efs in Southern Lazio, despite several attempts, since

the families of Paul Vs successors invested in that area, so they increased

their properties in Sabina instead, where they built up a compact territory.12 This continuing expansion is quite unique amongst papal families,

which normally stopped increasing their patrimony after the popes death.

The long duration of the Borghese ponticate explains it in part, since the

family had accumulated such extensive nancial power that they were the

only ones able to compete with new reigning families. They also had other

investments they could liquidate in order to buy new efs, such as shares

of the public debt. Above all, their great wealth allowed them to become

11

Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese, 194-235.

Forclaz, Les Borghese, 33-58; for the number of vassals, see Archivio di Stato di Roma

(=ASR), Congregazione del Sollievo 1-2, fasc. 2/10; for the hierarchy of landowners in the

Agro romano, see M. Teodori, La propriet fondiaria a Roma a met Seicento. Le tenute

dellAgro romano, in D. Strangio (ed.), Studi in onore di Ciro Manca (Padua, 2000), 555600.

12

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

175

the creditors of other nobles, whose estates they would eventually seize.13

This policy shows the Borghese familys growing interest in efs after

Paul Vs death. While efs represented 46% of the value of the familys

landed properties in 1621, their share increased to almost 60% in 1658.

Although efs were less protable than allodial properties in the Agro

romano, the prestige and power derived from enjoying jurisdiction over

vassals made them attractive investments. Territorial considerations appear

in some investments: in 1633, Marcantonio Borghese exchanged the ef of

Rignano for the state of Canemorto, in Sabina, which consisted of four

villages, less protable than Rignano but situated next to Marcantonios

other possessions. After Marcantonios death 1658, his patrimony was

inherited by his grandson Giovanbattista. The latter continued Marcantonios policy and expanded the familys territories in Sabina, with three new

efs purchased in 1678, with money from the sale of other lands and

nancial investments. He even contracted debts in order to pay for the

new estates. These choices brought some changes to the structure of the

Borghese patrimony. Whereas the landed properties represented 76% of

the whole in 1658, their share had increased to 83% when Giovanbattista

died in 1717. The share of nancial investments shrank to a mere 5%.14

After 1717, there were very few purchases or alienations. Throughout the

17th century, there was thus a double shift in the structure of the assets:

from nancial investments to landed properties and, among the latter, from

allodial to feudal estates. Several motives explain these modications: the

decreasing return from shares of the public debt after 1650, the extension

of the familys territories in Sabina, and possibly a desire to diversify crops.

The most important motivation appears to be the Borghese insistence on

their aristocratic rank on the Roman social scene following Pope Pauls

death. But while other papal familiessuch as the Barberiniput their

survival in the nobility at risk through excessive purchases during their

ponticate, the Borghese followed a more careful and gradual investment

policy, which allowed them to consolidate their status.

The Borghese acquired efs in Lazio in two districts, primarily. To the

northeast of Rome, the family owned a compact territory in Sabina, most

13

They lent for example 40,000 scudi to the Anguillara family in the 1620s and bought

the latters lordship Stabia in 1660 (ASV, AB 23/36, f. 23); they also lent in the 1630s

30,000 scudi to the Savelli family, which were refunded with the purchase of Castelchiodato and Cretone in 1656 (AB 27/138; AB 301/1).

14

Forclaz, Les Borghese, 81-82.

176

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

of which was bought between 1630 and 1660. In Bassa Sabina, a region of

hills close to Rome, the main rural specializations were wheat and livestock

raising, but also vines and olive trees. In Eastern Sabina, situated in the

mountains near the border with the kingdom of Naples, vineyards and

olive trees were rare. The main activities there were wheat-growing and

livestock-raising, complemented with hemp and chestnuts. The other area

where the Borghese owned several efs was Southern Lazio; but unlike in

Sabina, these efs were scattered.15 In the Monti Albani, wine was the main

production; in the hills of the Monti Prenestini, dierent crops were grown:

wheat, vines, olive and fruit trees; in the Monti Lepini, stock breeding and

cereals were dominant. To summarize, two typologies are important from

the geographic and economic point of view. In the efs located in the hills,

various crops were possiblecereals, vineyards, fruit and olive trees

whereas in the mountain areas, the economy was founded on grain, pasture and the exploitation of forests. Moreover, the proximity of roads in

Bassa Sabina and Southern Lazio allowed the commercialization of part of

the production in Rome or in the lesser towns of Lazio. As we shall see,

these dierences are also related to variations in the structure of the feudal

revenues.

Geography and Typology or the Feudal Rights

Which rights did the Borghese possess in their new efs? Ill focus here on

the banalits, manorial rights and property rights and, leaving aside rights

of justice (these proved to be very signicant in Lazio, since the Borghese,

like other families belonging to the high nobility, held penal and civil jurisdiction as well as the right to hear appeals and to pronounce the death

penalty). Apart from its relevance in terms of authority and prestige, which

was stressed by the possesso, a ceremony during which the inhabitants

had to take an oath of allegiance to their new lord, jurisdiction authorized

the lord to collect a variety of dues.16 What did these consist of ? First, there

15

About Lazio and its geography, see ASV, AB 3018; P. M. C. De Tournon, tudes

statistiques sur Rome et la partie occidentale des tats romains, Paris, 1831; F. NobiliVitelleschi, Relazione del Commissario Marchese Francesco Nobili-Vitelleschi . . ., in Atti della

Giunta per la Inchiesta agraria e sulle condizioni della classe agricola, vol. XI (Rome,

1883-84).

16

On this issue, see D. Armando, I poteri giurisdizionali dei baroni romani nel Settecento: un problema aperto, in Dimensioni e problemi della ricerca storica, 1993, 2, 209239; Forclaz, Le relazioni complesse.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

177

were property rights, rents and levies paid by the inhabitants who cultivated the lands owned by the lord. They were generally paid in kind and

amounted to 1/6th-1/4th of the crops. This deduction was extremely high,

since in the Kingdom of Naples, it generally amounted to 1/10th of the

crops.17 Next there were banalits, mainly the seigneurial monopolies (of

the mill, the oven, the inn or the oil press), to which the whole population

of the ef was subject. In some efs, tolls existedtaxes on merchandise

or passengers travelling through the jurisdiction. There were also contributions in kind (such as Christmas dues). Finally, the few manorial rights

consisted of personal labour contributions, the corves, which were in some

cases substituted by a monetary contribution.

The balance among these rights varied from one district to another. In

pastoral Eastern Sabina, feudal rights were diverse and heavy. Some manorial rights existed: the vassals were obliged to bring every year the dues in

kind to the lords storehouses in Rome for a very low salary. In some of the

efs, there were still corves (that is, unpaid labour details)one or two

days a year. As for banalits, the lord generally possessed the monopoly of

the oven; furthermore, he inherited the belongings of the inhabitants who

died without an heir. In Canemorto and the bordering efs, the owners of

animals had to pay a fee. Finally, the vassals had to pay contributions in

kind to the lord at Christmas or Easter. With respect to property dues, the

levies varied between 1/6th and 1/4th of the crops, a considerable share.18

In Bassa Sabina, the situation was quite dierent. In the ef of Palombara,

there were many fewer rights, for example no corves, and no contributions

in kind. Banal rights included the monopoly of the oven and of the oil

press, and a toll on transiting merchandise. The levies paid by the tenants

of feudal lands amounted here to 1/5th of the crops.19 In southern Lazio,

the situation was comparable to Bassa Sabina. In Montefortino, Olevano

and Norma, the property dues were dominant, and the levies were very

high1/4th of the crops. There were some contributions in kindfor

example in Norma, where all inhabitants had to give two chickens every

17

See G. Curis, Usi civici, propriet collettive e latifondi nell Italia Centrale e nellEmilia

con riferimento ai Demanii comunali del Mezzogiorno, Napoli, 1917; Pescosolido, Terra e

nobilit; for the Kingdom of Naples, see M.A. Visceglia, Territorio feudo e potere locale. Terra

dOtranto tra Medioevo ed Et Moderna (Naples, 1988), 121; Astarita, The Continuity of

Feudal Power, 82.

18

ASV, AB 2764.

19

ASV, AB 732/9, 732/141.

178

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

year to the lordand some fees, but on the whole the banal rights were

fewer than in Eastern Sabina, and there were almost no corves. As for the

monopolies, the lord held that of the oven or of the millbut there were

dierences between the single efs.20

The division of landed property ownership conrms these sub-regional

divisions. According to the general cadastre of the Papal State of the late

1770s, in Eastern Sabina, the Borghese owned about 1/3 of the land. In

Bassa Sabina, their share amounted to 40%, and in southern Lazio, the

situation was more diverse: in the Monti Albani, the portion of the land

directly owned by the lord was very low, whereas in the Monti Lepini, it

came to more than the half of the land.21 We should emphasize that manorial and banal rights were important where the lords share of the land

ownership was low, whereas elsewhere, property rights brought in higher

income and manorial dues proved less important. Areas where seigneurial

land ownership was low were also poor villages situated in less fertile

mountain areas, where landed incomes were lower. In these regions, the

lords sought to maintain their banal rights, which aected the whole population and depended less on agricultural productivity.

How can we explain these dierences? The lack of research on seigneurial

dues in 16th-century Lazio makes it dicult to know the previous history

of the efs, although the few studies available seem to indicate that the

lords tried to impose new rights upon their vassals in the 16th century.22

One could also relate the hardening of landlord pressure in Eastern Sabina

to a lack of municipal statutes, for such laws regulated the relationships

between the lords and their subjects as well as the political and judicial

organization of the communes. There is a signicant dierence between

the regions where the Borghese owned their efs in this regard: whereas in

Southern Lazio and in Bassa Sabina, nearly all of the communes were provided with statutes, in Eastern Sabina, most villages lacked them. It seems

likely that these communities, which were small and isolated, found themselves in a weaker position with respect to the bigger villages. Historical

factors also testify to the strength of the communes in the former regions:

20

ASV, AB 579/12, 582/101, 703/22, 715/42bis.

Pescosolido, Terra e nobilt, 70-77.

22

C. Iuozzo, Feudatari e vassalli a Vignanello. Un caso di lotta politica e giudiziaria nella

seconda met del Cinquecento (Viterbo, 2003), 25, 110-11, 119-20, 151-52.

21

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

179

in Bassa Sabina, there were some free communes in the late Middle Ages,

whereas in Southern Lazio, the cities were more numerous.23

The Growth of Feudal Rights in the 17th Century

Upon acquiring new efs, the Borghese tried to increase their right.

Paul Vs reign represented a favorable period, as the family wielded papal

authority over the communes. In 1613, Paul V provided his nephew, cardinal Scipione Borghese, with the monopoly of the mill in all his efs. The

Borghese also bought some new rights from indebted communes in Sabina,

mainly monopolies, in the years 1611 and 1612. This policy continued

after 1621, but new opportunities presented themselves less often.24 In

several efs, in the 1620s and 1630s, the Borghese also tried to impose new

banal rights, in particular the monopoly of the oven, by forbidding private

ovens. In other efs, where there was no monopoly, the lords stewards

tried to force subjects to use the seigneurial mill by forbidding them to

grind their cereals outside the village.25 In all these situations, jurisdiction

was an essential tool to this policy, as the lord promulgated edicts and local

tribunals prosecuted the oenders.26

This policy of hardening the feudal rights was also extended to the

landed dues: in 1633, in Montecompatri, the Borghese introduced a levy

on fruit production, but after a petition of the commune, the familys

administrators stepped back.27 In some cases the Borghese tried to force

the inhabitants to lease their lands right after the purchase of the ef. At

the end of the 17th century, when some communes in Sabina were heavily

indebted to the lords, they agreed to cultivate the lords lands in exchange

for the cancellation of their debts.28

23

Forclaz, Les Borghese, 113.

See Reinhard, Papstnanz und Nepotismus, vol. I, p. 26; ASR, Segretari e Cancellieri

della Reverenda Camera Apostolica, vol. 367, . 430r-431v, 451r/v, and vol. 393, . 362r365v; ASV, AB 150/1 and AB 2879, f. 4; AB 702 /24, 722/443 and 736/258.

25

ASV, AB 327/73; ASV, AB 579/12, letter of Francesco Eusebij, 10 November 1634;

ASV, AB 582/18, edicts of 1637 and 1638; ASV, AB 582/88.

26

Forclaz, La famille Borghese, 78-81.

27

Archivio storico del comune di Montecompatri, Archivio preunitario, 1/2, Consiglio

1616-1647, f. 216v.

28

ASV, AB 648/16, 648/64, 648/79; ASV, AB 2876, . 24-27.

24

180

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

Such forceful initiatives led to conicts with the inhabitants, and especially with the communesjust as in the Kingdom of Naples.29 Interestingly, conicts about monopolies concerned mainly the efs of Southern

Lazio, where property rights were predominant, while in Eastern Sabina

the antagonisms focused around manorial rights. After they purchased

Canemorto, the Borghese sought to increase the quantity of wheat the

commune had to transport every year to Rome.30 Whereas the communes

had opposed previous lords in several lawsuits before the papal tribunals in

the late 16th and early 17th century, after the acquisition of the efs by the

Borghese the number decreased sharply. The new lords acted carefully and

backed up their claims by buying new rights, signing agreements with the

communes or imposing a monopoly only gradually. Their dominant position within the Curia, during Paul Vs reign, also forestalled the intervention of Roman magistracies against them.

Growing Conicts in the 18th Century

The situation changed for the Borghese in the early 18th century. Some

communes contested seigneurial rights, and the central magistracies were

bent on verifying their extent. In 1704, Pope Clement XI taxed the properties of lords in their efs and subjected communes to the jurisdiction of the

Congregazione del Buon Governo, in charge of supervising local nances.31

This decision led to surveys of the communes by Roman prelates, who

wanted to check possible seigneurial abuses, such as undue fees required

from the communes. The Congregations major concern was to reduce

communal debt. In the Borghese efs in Eastern Sabina, communal ocials

complained to the prelates about a number ofseigneurial rights (such as the

obligation to transport wheat to Rome and the taxes paid by the owners of

29

M.A. Visceglia, Comunit, signori feudali e ociales in Terra dOtranto tra XVI e

XVII secolo, in Archivio Storico per le Province Napoletane, CIV, 1986, 259-85; Astarita,

The Continuity of Feudal Power, 147-50; M. Benaiteau, Vassalli e cittadini. La signoria rurale

nel Regno di Napoli attraverso lo studio dei feudi dei Tocco di Montemiletto (XI-XVIII secolo),

Bari, 1997, 210-15.

30

ASV, AB 167/3; ASV, AB 151/66.

31

S. Tabacchi, Tra riforma e crisi: il Buon Governo delle communit dello Stato della

Chiesa durante il ponticato di Clemente XI, in Ph. Koeppel (ed.), Papes et papaut au

XVIIIe sicle. VIe colloque Franco-Italien organis par la Socit franaise dtude du XVIIIe

sicle (Paris, 1999), 51-85.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

181

animals) and about the monopolies sold to the Borghese by the communes.

The prelates then put together a list of the rights at issue and asked the

Borghese to justify them.32

In the years following these surveys, several lawsuits pitted inhabitants

of communes against the lord or the leaseholder. The new policy of the

papal authorities revealed the existence of a local elite whose interests

diverged from those of the Borghese. These lawsuits led to a fundamental

questioning of seigneurial rights. In Canemorto, for example, the commune in 1709 appealed to the Buon Governo against a decree ordering

inhabitants to carry wheat to Rome for the second time that year. Not only

did the commune refuse to do it, but it also identied carriage as a regalian

rightand therefore not due to the lord. These arguments did not convince the Congregation, which conrmed the controversial right.33 A similar evolution occured in Bassa Sabina, especially concerning property

rights. In Palombara, a long lawsuit opposed the commune to the lord

about levies on olive production. It all started in 1720, when the leaseholder, Gregorio Fargna, claimed dues on olives, cherries and other pitted

fruits produced in the vineyards belonging to the lordamounting to

1/5th of the production. The commune appealed to the Buon Governo

and claimed that there had never previously been any levy on olives. The

adversaries based their assertions on contradictory juridical texts: the commune referred to the statutes, which did not mention any dues on olives,

whereas the lord quoted the purchase contract for the ef, which did. The

suit went onwith some interruptionsfor half a century. Dierent

magistracies dealt with it, deciding alternately in favor of the commune

and the Borghese. At stake were around 10% of the total incomes of Palombara for the Borghese, and the commercialization of the olive oil produced by the vassals, who brought it to market in Rome. Eventually, the

commune won the case in 1770, when prince Marcantonio Borghese

withdrew from it.34 The defeat was not only material for the prince, but

also symbolic, especially after a fty-year struggle. But what were the origins of these growing conicts?

This evolution is clearly related to the development of peasant property

in the 18th century: due to demographic growth, wastelands belonging to

32

33

34

ASR, BG, IV, 980, . 4v, 13r, 5v/6r, 8r, 9r, 13r, 15r, 233r/v, 594r.

ASR, BG, II, 667; Forclaz, Les Borghese, 134-36.

ASR, BG II, 3321, 3323; ASV, AB 754-760; Forclaz, La famille Borghese, 349-52.

182

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

the lord were rented out to the peasants, and intensive crops were cultivated, such as olive trees, fruit trees or vineyards.35 Since investment was

necessary, these lands were only accessible to the upper and middle strata

of peasants. The conditions of the leases changed: the lord rented out these

lands at longer terms and commuted rents in kind into money payments.

This also transformed the relationships betweens the lord and his subjects,

as autonomous farmers emerged in the efs, who were able to commercialize part of their production on the Roman market. In Palombara, we nd

distinct features of this process. In the 18th century, more olive trees were

grown in orchards, and farmers tried to escape the levies by claiming that

they had never been collected on olives. They reinterpreted history according to the present situation, while clinging to the letter of the communal

statutes, which did not mention olive trees.36 The Borghese and their managers, on the other hand, tried to enforce traditional leviesone fth of

the harvestson a modern production, but they were not able to overturn the juridical arguments of their opponents. In other efs, though, the

Borghese adapted to the new situation by adopting new leasesin money

and not in kind. It is likely that the polarization of the conict made such

an evolution impossible in Palombara.

Thus, there was clearly an intensication of conicts in Lazioa trend

opposite to the one unfolding in the Kingdom of Naples, where conicts

lessened in the 18th century.37 Whereas in the 16th century, lawsuits were

mere reactions to feudal abuses, in the 18th century the vassals questioned seigneurial dues altogether. Once more, regional dierences are evident: whereas in Eastern Sabina, the conicts concerned taxes and transport

services, in Bassa Sabina, land rental dues were at stake. An emerging

autonomous rural elite sought to free itself from the lords grasp on the

local economy, by cultivating intensive commercial crops and developing

contacts with the Roman market.

35

Id., Les Borghese, pp. 151-155; the phenomenon is also testied to in the Kingdom of

Naples: Visceglia, Territorio feudo, 240-41; Astarita, The Continuity of Feudal Power, p. 86;

Benaiteau, Vassalli e cittadini, 349-52.

36

As did the inhabitants of the efs owned by the Barberini in a similar conict: see

Castiglione, Patrons and Adversaries, 164-66.

37

Astarita, The Continuity of Feudal Power, 151-54; Benaiteau, Vassalli e cittadini,

226 -27.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

183

Structure and Evolution of the Revenues

It is important to consider to what extent the elements described so far

regional dierences, increasing feudal rights in the 17th century and growing conicts in the 18thinuenced incomes brought in by the efs. Did

those incomes drop after 1700? And was the hardening of feudal dues

subsequent to a crisis of the revenues? In order to evaluate the importance

of feudal incomes, it is rst of all necessary to assess their monetary value

by comparing them with prices in 17th century Lazio. A team of oxen, for

example, cost about 50 scudi in the 1650s, whereas a rubbio of wheat,

which fed an adult for a year, cost in the same period between 7 and 8

scudi.38 At that time, the twenty-three efs held by the Borghese yielded

almost 40,000 scudi a year, a sum inconceivable for a local farmer. However, there were signicant dierences between efs: Palombara brought in

about 7500 scudi, but Vallinfreda only 650 scudi. This gap was related to

demographic and geographic variables; in order to explain it, it is worth

examining rst the structure of the incomes. In Eastern Sabina, the share

of land-use payments in the overall revenues was rather low:39 in 1637, in

Canemorto, it constituted only 32.9% of the income, in Vivaro 41.2%, in

Scarpa 32.5%. The monopolies, on the other hand, represented an equal

or more important share of the revenues: 34.5% in Canemorto, 45% in

Vivaro, 53.4% in Scarpa. The other banal and manorial rights (corves,

various taxes and contributions) brought in 28.8% in Canemorto, but

only 7% in Scarpa and 5.4% in Vivaro, as did the pastures (4% in

Canemorto, 8.3% in Vivaro, but 20.9% in Scarpa).

Table 1: Revenues of Eastern Sabina, 1637 (in scudi)

Levies

Monopolies

Other banal rights

Pastures

Total

38

39

Canemorto

Vivaro

Scarpa

353.8

372

310.9

42.8

1079.5

301.5

330

40

61.1

732.6

240

341.5

22.5

160

764

Ago, Un feudo esemplare, 54; ASV, AB ASV, AB 8567, f. 418 v/r.

ASV, AB 2764.

184

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

The situation was quite dierent in Bassa Sabina:40 the levies and incomes

from pastures and forests represented the principal part of the revenue. The

former constituted 45.3% of the total incomes of Palombara, 50.3% of the

incomes of Moricone and 37.8% of those of Mentana, while the latter

brought in respectively 37 (Palombara), 29.1 (Moricone) and 45.2%

(Mentana). Accordingly, monopolies and other banal and manorial rights

represented a low share of the revenue: 17% in Palombara, 18.7% in Moricone and 17% in Mentana. Whereas in Mentana, the agricultural incomes

came almost exclusively from wheat, in Palombara and Moricone, they

also included vine and olive oil production (10-15% of the total rent). In

these efs, the land-use payments (levies and rentals of pastures) amounted

to 80% of the revenues.

Table 2: Revenues of Bassa Sabina, 1649/56 (in scudi)

Palombara

(1649)

Levies

Monopolies

Other banal and

manorial rights

Pastures, exploitation

of forests

Total

Moricone

(1654)

Mentana

(1656)

3442.5

1114

244.91

142.1

484.6

44.6

2413.2

1086

0.5

2802.5

823.1

2890.8

7603.9

2827.6

6390.5

In Southern Lazio, the revenue structure is similar to that of Bassa Sabina,

with the predominance of land-use fees more pronounced (63% in Montecompatri and Monteporzio, 52.6% in Montefortino, 70% in Norma);

rentals of pastures and forests represented 23.6, 35.3 and 21.4%, while

monopolies brought in only13, 8.4 and 7%. There was ample agricultural

specialization between the dierent efs: in Montecompatri and Monteporzio, vineyards were dominant (40% of the rent), whereas in Montefortino and Norma, the production consisted mainly of wheat.41

40

41

ASV, AB 8566, f. 169, 223; ASV, AB 8567, f. 213, 394.

ASV, AB 327/60; 703/23; 8566, f. 165, 238.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

185

Table 3: Revenues of Southern Lazio, 1635/1650 (in scudi)

Levies

Monopolies

Other banal and

manorial rights

Pastures, exploitation

of forests

Total

Montecompatri/

Monteporzio

(c. 1635)

Montefortino

(1650)

Norma

(1630s)

3791

725

60

3390.3

551

225.4

1863

180

65

1413

2280.9

575

5989

6447.5

2683

On the whole, then, we observe a striking diversication of income between

the dierent regions: whereas in Eastern Sabina, the share of monopolies

and other banal rights was important (around the half of the revenue),

in Bassa Sabina and in Southern Lazio, revenue mainly consisted of payments for the use of land. And in these regions, there was also a greater

diversication of crops: in Bassa Sabina, incomes from vineyards and olive

trees represented a signicant part of the total, whereas in Southern Lazio,

some efs were specialized in wine production and others in wheat and

livestock breeding. Thus, as in Southern Italy, the Borghese familys feudal

investments in dierent regions appear to have hedged against the variations in production, as not all crops would have bad harvests the same

year.42 Furthermore, in most efs, levies and other land-use payments constituted the main share of the revenue. Banal and manorial rights were

only important in the poorer efs of Eastern Sabinaa conclusion which

conrms Tommaso Astaritas results for the efs of the Caracciolo di Brienza

family in the Kingdom of Naples.43 In richer regions of Southern Italy

like Sicily or Pugliathe latter were not signicant for seigneurial income.

This does not mean, as many assumed in the 1970s and 1980s, that feudal

42

That behavior follows the model that has been established by Witold Kula for Poland:

see W. Kula, Thorie conomique du systme fodal. Pour un modle de lconomie polonaise

16 e-18 e sicles (Paris-La Haye, 1970), 42; for Southern Italy, see M. A. Visceglia, Lazienda

signorile in Terra dOtranto nellet moderna (secoli XVI-XVIII), in A. Massafra (ed.),

Problemi di storia delle campagne meridionali nellet moderna e contemporanea (Bari, 1981),

44-45, 63.

43

Astarita, The Continuity, 78-80.

186

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

lords in the early modern period became mere landowners deprived of

jurisdictional or political power in their efs.44 What subsequent research

has shown is that land-use income became the principal origin of their

revenues.

With such dierences in the structure of the revenues, the question of

their evolution over time and of the overall conjuncture becomes important. Did the raising of the charges for manorial and banal rights in the

17th century have consequences for the seigneurial income overall, or did

it just compensate for a previous diminution? And did the conicts of the

18th century lead to a decreasing of overall income? Finally, can one discern similar uctuations of revenues in the dierent regions? As to the rst

question, we lack evidence for the revenues from the efs in question at the

beginning of the 17th century, before purchase by the Borghese family. In

some cases, there was a revenue increase: in Eastern Sabina, in the years

after the purchaseas the new lords bought some monopolies from the

communesthe income went up by 25 to 33%.45 In Southern Lazio, revenue remained stable in the rst half of the 17th century.46 The incomes of

the monopolies increased, though, mainly in Montefortino (from 78 to

515 scudi between 1615 and 1649),47 but this did not aect the overall

income.

Did increasing incomes from monopolies represent an answer to a

reduction of landed incomes? In fact, they were a consequence of the rural

crisis in 17th-century Italy. For Rome as well as for Southern Italy, the

starting point of the crisis can be dated back to the middle of the century,

thus later than in north-central Italy, where the crisis began in the 1620s.

Although it can best be described as a deation rather than a Malthusian

crisis, it started in a classical way with a demographic catastrophe, the epi-

44

Aymard, La transizione, 1191-192; Pescosolido, Terra e nobilt, 50-51; critics to this

position in Astarita, The Continuity, p. 71. On the political and jurisdictional powers of the

lords, see, for the Kingdom of Naples, Astarita, The Continuity; for the Papal State, see

Armando, I poteri giurisdizionali; Forclaz, Le relazioni complesse; Forclaz, La famille

Borghese.

45

Percile and Civitella, rented out 1000 scudi in 1610, are rented out 1300 scudi in

1613; the revenues of Vivaro increased from 450 (1612) to 680 scudi (1616), while those

of Scarpa went from 800 to 1000 scudi between 1612 and 1620 (Reinhard, Papstnanz und

Nepotismus, vol. I, . 122, 124, 126).

46

Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese, . 204-09, 220-21.

47

ASV, AB 582/101; ASV, AB 8566, f. 165r.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

187

demic plague in 1656, which aected rst the Kingdom of Naples, then

the Papal States and Genoa. Due to this severe mortality, rst demand and

then supply shrank. Consequently, feudal incomes lessened, as land-rents,

grain prices and incomes from monopolies and other banal rights all contracted. Signicantly, the revenues rst crashed in Eastern Sabina, which

bordered on the Kingdom of Naples: they shrank at least one third between

1654 and 1659, and in some cases by 50%.48 In 1680, the revenues were

one-quarter lower than in the early 1650s.49 In Bassa Sabina, the diminution took place later than in Eastern Sabina. In 1680, the income regressed,

although less than in Eastern Sabinaprobably due to the diversity of

crops and to the weaker eects of the plaguebut at the beginning of the

18th century, the contraction of revenues was pronounced there too. In

Southern Lazio, nally, although incomes remained high throughout the

17th century in Montecompatri and Monteporzio (the efs that were specialized in vineyards), other efs registered an evolution similar to Bassa

Sabina: levies diminished, while the relative share of monopolies increased.

The regression was less than in Eastern Sabina.

The response of the Borghese assumed dierent forms: on one hand,

they increased their pressure on local communities. In Eastern Sabina they

bought monopolies from some communes and forced the inhabitants of

other efs to cultivate seigneurial lands, probably where the population had

regressed after the plague. Incomes from monopolies remained constant

and increased in some cases, following population growth. It is possible

that the Borghese and their leaseholders, in order to cut down production

costs, abandoned grain cultivation in elds that were converted to grazing

lands. Another policy, starting in the last decades of the century, conceded

lands to peasants for long-term monetary rents. In many efs, when the

population increased again, monetary incomes grew from planting new

intensive crops such as vineyards and olive trees. Incomes from pastures

and forests lessened proportionally, because of land reconversion. This latter policy spurred the growth of peasant property in the 18th century and

gave greater autonomy to the farmers, creating the conditions for future

48

ASV, AB 8567, f. 622v, 624v.

ASV, AB 8572, f. 853, 860, 873-74. About the rural crisis, especially in north-central

Italy, see G. Hanlon, Early Modern Italy, Basingstoke, 2000, 217-19; for Tuscany, see lately

G. Hanlon, Human Nature in Rural Tuscany: an Early Modern history, Basingstoke, 2007,

chapter 4; for grain prices in Rome and the Papal State, see Reinhardt, berleben in Rom,

311-331.

49

188

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

conicts between the lords and their subjects. It is not possible to examine

the further evolution of the revenues, as we do not know their composition

after the Borghese rented out their efs in the 18th century. Nevertheless,

we observe a slight revenue increase from 1720 onwards.

Beyond the question of the evolution of revenues, we must keep in mind

the protability of the efs as compared to other assetsallodial estates

and nancial investments. Around 1600, the income from efs has been

estimated at between 2.5 and 3% of their value, whereas in 1660, it

dropped to only 2.1%; similarly, the income of allodial estates fell from

3.5-4% circa 1615 to 3% in the 1660s.50 Financial investments were more

protable, as the shares of the public debt yielded between 4.5 (for the

transmissible bonds) and 7.5-9% (for the non-transmissible bonds) around

1600.51 However interest rates later went down to 4% for transmissible

bonds in 1656, and to 3% in 1683. Although the protability of efs and,

more generally, of landed properties was not very high, their attractiveness

competed by default with that of nancial assets.

Management Choices

How did the Borghese collect their revenues? Two options were available:

leasing or direct management. As the Borghese lived in Rome and not in

their efs, they needed intermediaries for both. In most efs, the prosecutor of the feudal tribunal was in charge of collecting dues, selling grain and

leasing out the seigneurial lands. Each individual ef was part of a bigger

structure, however: in Sabina, general superintendents based in Canemorto

and Palombara supervised the management of the other efs, gathered in

two feudal states. In Southern Lazio, a superintendent living in the

Borghese summer villa of Frascati managed the neighboring efs of Montecompatri and Monteporzio, while further south, the steward of Montefortino also ran Norma and Olevano. While prosecutors generally belonged

to the local elites, superintendents often came from other efs.

50

For the following gures, see Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese, p. 194; M. Teodori,

I parenti del papa. Nepotismo ponticio e formazione del patrimonio Chigi nella Roma barocca

(Padua, 2001), 174, 198.

51

The transmissible shares could be inherited at the death of the owner, whereas the

non-transmissible shares went back to the state.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

189

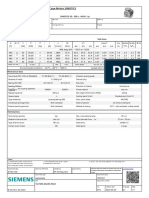

Revenues of the efs between 1650 and 1763 (in scudi)

45 000

40 000

35 000

30 000

25 000

20 000

15 000

10 000

5 000

0,00

1650'

1680

Southern Lazio

1700'

Bassa Sabina

1720

1744

Eastern Sabina

1763

Total

If seigneurial assets were rented out, however, a leaseholder managed them.

Since rental contracts generally lasted six or nine years, the leaseholder was

undoubtedly a key gure in the ef. The major dierence between direct

management and leasing is that when the efs were rented out, the leaseholderand not the lords stewardshad to take care of leasing the lands,

collecting the rents and commercializing the dues collected in kind. Stewards and leaseholders had to respect several constraints: rst, they were

obliged to rent out the lands to the farmers of the village, since only the

latter had the right of cultivating them. Every third or fourth year, according to crop rotation schedules, seigneurial lands were distributed among

the owners of oxen. Likewise, the inhabitants held access rights to pastures

and forests owned by the lord.52

What made the Borghese choose between direct management or leasing

out? Several factors made leasing an easier option. First, the lord and his

stewards did not have to worry about leasing the lands, or about collecting

dues or debts from peasants, which were important in the Ancien Rgime.

52

See Curis, Usi civici, pp. 473-485, 528-567, 732-739; Pescosolido, Terra e nobilt;

R. Ago, Un feudo esemplare. Immobilismo padronale e astuzia contadina nel Lazio del 700

(Fasano, 1988).

190

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

Even in bad years, the leaseholders always had to pay rent to the Borghese.

On the other hand, direct management could bring in more prots by

eliminating the middleman, but one has to consider the costs it entailed.

At the end of the 17th century, expenses (salaries of the feudal ocers,

maintenance of mills, expenses for the harvest) often represented more

than 20% of the incomes, whereas they constituted only 10% of the rent

in the leased efs.53

In Lazio as in Southern Italy and elsewhere in Europe, the lords rented

out their efs from the second half of the 16th century on. By then many

leaseholders were Roman commercial farmers, the mercanti di campagna;

sometimes even bankers took part in the lease. As soon as they bought

their efs, the Borghese rented out almost all of them. After Paul Vs death,

this remained the preferred option. Until the middle of the 17th century,

most efs were leased out, excepting the most desirable of themMontefortino, Palombara and Mentana. During the second half of the century,

the Borghese rented out fewer efs, since the prots lessened for leaseholders.

Many of the latter discontinued their lease, and by the 1680s, only ten of

thirty-two efs were leased outthis time the most protable ones. How

can we explain this evolution? In the 1650s, it was possible for the farmers

and their stewards to sell the wheat for high prices. Thirty years later, the

cultivated areas had declined and so had the production, which explains

the loss of interest on the leaseholders side and the fact that only the bigger

efs were rented out. In 1650 direct management of the bigger efs was

lucrative for the Borghese, but after 1680 it ceased to be attractive.54

At the beginning of the 18th century, two-thirds of the efs remained

rented out.55 The decline of revenue was probably due to the bankruptcy

of several leaseholders in the late 17th century. The Borghese then consolidated the contracts until only ten leaseholders rented twenty-one efs.

During the 18th century, direct management became quite exceptional,

and businessmen holding long-term leases managed the efs. In Southern

Lazio, the Tuschi family leased Norma uninterruptedly from the 1720s to

the end of the century.56 Who were the other leaseholders? During Paul Vs

53

Forclaz, Les Borghese, 204.

About the leaseholders in the Papal State, see Delumeau, Vie conomique, vol. I, 48182; for the early 17th century, see Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese; in Southern Italy,

see Aymard, La transizione, 1141-42; Astarita, The Continuity, 67.

55

ASV, AB 23/33, 25/54, 29/240, 7650.

56

ASV, AB 327/103, 582/33, 705/253, 705/240, 705/246.

54

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

191

reign, some of them were Roman bankers, but the latter seemed to take

less interest in farming in the second half of the century; some leaseholders

were merchants active in the capital. Others came from the lesser towns of

Lazio, where they had other activities. In the 1650s, the leaseholders of

Norma also leased the oven of the neighboring city of Velletri. Finally,

many emerged from the elites of the efs themselves: they leased in particular the smaller ones, especially in Sabina.57

Although the Borghese preferred renting out their efs, they demonstrated an interest in management nevertheless, taking part in negotiations

with potential leaseholders and keeping informed about prices of wheat.

One of the main problems of direct management was the sale of dues collected in kind. Due to their centralized administrationthe stewards of

the bigger efs supervised the management of the smaller ones, especially

in Sabinathe Borghese often sold wheat from one ef to another, or to

the Roman market and to bakers of lesser towns. The Borghese and their

administrators seemed to prefer reliable buyers, able to buy large quantities. An important part of the grain was also sold to the inhabitants of the

efscommunes and bakers for supplying the population, peasants for

seeds. The inhabitants, as small-scale purchasers, often had to buy it at a

more expensive rate than foreign buyers: in 1644 for example, the baker of

the city of Tivoli bought wheat for 6.5 scudi a rubbio, while the baker of

Palombara paid 8 scudi.58 There were important commercial movements

on a regional scale, within Sabina, and from efs situated in Sabina to

those in Southern Lazio. The Borghese attention to the commercialization

of their revenues in kind diers from the policy of lords belonging to the

old nobility, who preferred to sell their wheat to the communes of their

efs.59 It seems that, while the Borghese respected the moral economy,

i.e. the duty of supplying their subjects with their own produce, they put

their economic interest rst, especially in years of shortages, as regards to

both the buyers and the prices.

57

Forclaz, Les Borghese, 206-08.

ASV, AB 737; other examples in AB 326/42; AB 8566, 141, 271, 350, 352, 699; AB

8567, 204, 245, 405, 539, 549.

59

Astarita, The Continuity, 92; Benaiteau, Vassalli e cittadini, 299; Raimondo, Il prestigio, 125.

58

192

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

Conclusion

The management of the Borghese clearly displayed traditional features:

they made few investments and their main goal was to guarantee a stable

income. Moreover, they followed an aggressive policy to increase their

incomes during Paul Vs ponticate through the imposition of new

monopolies. Towards the end of the 17th century, again, they tried to

squeeze their vassals in order to oset the decline of their incomes. However, it is legitimate to emphasize their commercial acumen too.60 Several

elements indicate this: the purchase of efs in the later 17th century showing distinctions in the structure of the revenues, and a diversication of

crops; and more generally the ability of the Borghese to adapt to the situation and to take advantage of it. In Eastern Sabina they enforced banal and

manorial rights; in Bassa Sabina, they tried to improve revenues by extending traditional levies to new crops, like olives. They also proved to be careful managers in the commercialization of wheat. As they collected a wide

range of dues and owned an important share of the lands, their power over

vassals was extremely strong, especially in Bassa Sabina and in some efs of

Southern Lazio. In the 18th century, though, there was a substantial shift

and the lords position weakened. This was due to the development of

peasant property, strengthening relations between the peasants and the

Roman market, and the diminution or stagnation of the feudal revenues.

However, the Borghese still owned an important part of the land and collected important incomes from their efs. This evolution shows the importance of legal conicts over the long duration, and the active role of the

communes in changing the balance of power.

Seigneurial rights in Lazio thus proved to be extremely signicant

throughout the early modern period and the lords position was comparable to that of lords in Southern Italy. The renewal of the feudal nobility in

the 17th century allowed a signicant hardening of seigneurial rights, and

more research is needed on the transition from the 16th to the 17th century. Did this only apply to the papal families, or did new lords belonging

to curial or patrician families exert a similar pressure on their efs? Were

seigneurial rights hardened as well in efs retained by the old nobility? It

would also be interesting to determine whether the Borghese management

60

For the denition of a traditional management, see Astarita, The Continuity, 69-70;

about the commercial elements, see Reinhardt, Kardinal Scipione Borghese, 129-31.

B. Forclaz / Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008) 169-193

193

resembled that of other feudal lords, especially among the newcomers. But

even conceding this, it would be an oversimplication to put this pattern

of estate-management into a generic framework of traditional rural

economy. This study shows that the opposition traditional / modern

needs to be softened, as modern elements could be brought into a model

characterized by strong seigneurial rights. In the 17th century, the Borghese created vast estates and centralized the management of their efs, especially as regards the commercialization of revenues in kind. The choice

between management optionswhether direct or renting outwas based

upon considerations of prot. In this, the Borghese were similar to French

or Prussian noble families. Traditional seigneurial rights remained in all

cases important throughout the early modern periodand to some extent

they were even consolidated; yet the lords also showed a concern for commercialization of assets and for a rigorous management of their efs.61

Another modern element is agricultural innovation: although the Borghese did not initiate it directly, they cleared lands, brought in new kinds of

leases, and allowed the farmers to introduce intensive crops. This led to the

growth of peasant property and the development of new productions. In

Lazio as well as in other Western European countries, innovation and productivity growth came from small and medium exploitations, but the lords

encouraged a certain degree of specialization and might have given the

local farmers a model for the commercialization of their own production.

In the early modern economy, commercial and feudal features, far from

being mutually exclusive, were therefore intertwined.

61

See Hagen, Ordinary Prussians; Janssen, Yun-Casalilla (eds.), European Aristocracies.

You might also like

- Quezon City Department of The Building OfficialDocument2 pagesQuezon City Department of The Building OfficialBrightNotes86% (7)

- Collaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFDocument32 pagesCollaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFIvan CvasniucNo ratings yet

- NEW CREW Fast Start PlannerDocument9 pagesNEW CREW Fast Start PlannerAnonymous oTtlhP100% (3)

- (The Medieval Countryside - Volume 5) Sverre Bagge, Michael H. Gelting, Thomas Lindkvist (Eds) - Feudalism - New Landscapes of Debate (2011, BREPOLS)Document235 pages(The Medieval Countryside - Volume 5) Sverre Bagge, Michael H. Gelting, Thomas Lindkvist (Eds) - Feudalism - New Landscapes of Debate (2011, BREPOLS)Reyje KabNo ratings yet

- The Thirty Years' War, Serfdom, and the Rise of Absolutism in Seventeenth-Century BrandenburgDocument35 pagesThe Thirty Years' War, Serfdom, and the Rise of Absolutism in Seventeenth-Century BrandenburgAlbert Lance100% (1)

- American Indians, Witchcraft, and Witch-HuntingDocument5 pagesAmerican Indians, Witchcraft, and Witch-HuntingAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Geneva IntrotoBankDebt172Document66 pagesGeneva IntrotoBankDebt172satishlad1288No ratings yet

- Difference Between OS1 and OS2 Single Mode Fiber Cable - Fiber Optic Cabling SolutionsDocument2 pagesDifference Between OS1 and OS2 Single Mode Fiber Cable - Fiber Optic Cabling SolutionsDharma Teja TanetiNo ratings yet

- Ebook The Managers Guide To Effective Feedback by ImpraiseDocument30 pagesEbook The Managers Guide To Effective Feedback by ImpraiseDebarkaChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Aci 207.1Document38 pagesAci 207.1safak kahraman100% (7)

- Origin Modern StatesDocument8 pagesOrigin Modern StatesRommel Roy RomanillosNo ratings yet

- The Village Labourer, 1760-1832 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study in the Government of England Before the Reform BillFrom EverandThe Village Labourer, 1760-1832 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study in the Government of England Before the Reform BillNo ratings yet

- Rise and Growth of Feudalism According to Perry Anderson and Jacques Le GoffDocument7 pagesRise and Growth of Feudalism According to Perry Anderson and Jacques Le GoffBisht SauminNo ratings yet

- Peasant Based Societies Astarita Sobre Wickham PDFDocument27 pagesPeasant Based Societies Astarita Sobre Wickham PDFDiana VitisNo ratings yet

- The Three OrdersDocument8 pagesThe Three OrdersRamita Udayashankar75% (12)

- What Is FeudalismDocument9 pagesWhat Is FeudalismNikhin K.ANo ratings yet

- The Pirenne Thesis on the Impact of Islamic ExpansionDocument14 pagesThe Pirenne Thesis on the Impact of Islamic ExpansionAlok ThakkarNo ratings yet

- The Origins of The French Revolution: A Tale of Two Cities'Document6 pagesThe Origins of The French Revolution: A Tale of Two Cities'Sujatha MenonNo ratings yet

- History Stuff IdkDocument44 pagesHistory Stuff IdkNina K. ReidNo ratings yet

- Fuedalism: As A New Social Fabric BY: Vedant Nagpal (1806)Document3 pagesFuedalism: As A New Social Fabric BY: Vedant Nagpal (1806)Vedant NagpalNo ratings yet

- ABSOLUTISMDocument14 pagesABSOLUTISMcamillaNo ratings yet

- ABSOLUTISMDocument14 pagesABSOLUTISMcamillaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document5 pagesChapter 6Brahma Dutta DwivediNo ratings yet

- Crises of the Middle AgesDocument9 pagesCrises of the Middle AgeslastspectralNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 OutlineDocument14 pagesChapter 12 OutlineGabriel LeeNo ratings yet

- JCC - Battle of ViennaDocument17 pagesJCC - Battle of ViennaEnache IonelNo ratings yet

- PDF document-AF1BA08E8E3F-1Document49 pagesPDF document-AF1BA08E8E3F-1Taha HassanNo ratings yet

- Crisis of FeudalismDocument5 pagesCrisis of Feudalismanshumaan.bhardwajNo ratings yet

- Factors Responsible for Transition from Feudalism to CapitalismDocument10 pagesFactors Responsible for Transition from Feudalism to CapitalismAmanda MachadoNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Rebirth in ItalyDocument134 pagesRenaissance Rebirth in ItalyHeather FongNo ratings yet

- [German History 1988-apr 01 vol. 6 iss. 2] Asch, R. G. - Estates and Princes after 1648_ The Consequences of the Thirty Years War (1988) [10.1093_gh_6.2.113] - libgen.liDocument20 pages[German History 1988-apr 01 vol. 6 iss. 2] Asch, R. G. - Estates and Princes after 1648_ The Consequences of the Thirty Years War (1988) [10.1093_gh_6.2.113] - libgen.liHans Von RichterNo ratings yet

- European History: The French Revolution of 1789Document77 pagesEuropean History: The French Revolution of 1789Ruvarashe MakombeNo ratings yet

- Unit 14Document10 pagesUnit 14ShreyaNo ratings yet

- CHARLES III: The Enlightment Depotism: Historical SettingDocument4 pagesCHARLES III: The Enlightment Depotism: Historical SettingRichard Taylor PleiteNo ratings yet

- 3 Orders NotesDocument5 pages3 Orders Notesrwaliur78No ratings yet

- French Revolution Cultural StudyDocument19 pagesFrench Revolution Cultural StudySaurabh Krishna SinghNo ratings yet

- A History of Anarcho-SyndicalismDocument363 pagesA History of Anarcho-SyndicalismHamidEshani50% (2)

- UNIT 1 - The 18 Century in Europe: Absolute MonarchyDocument14 pagesUNIT 1 - The 18 Century in Europe: Absolute MonarchyBoom GT GamesNo ratings yet

- Causes of French Revolution (IEEE Format)Document9 pagesCauses of French Revolution (IEEE Format)Abdussalam80% (5)

- Absolutism ArticleDocument7 pagesAbsolutism ArticleNicolas JonesNo ratings yet

- Name-Amisha Choudhary Roll No. - 19/413 Class-3 Year 5 Sem Assignment-Factors That Led To French Revolution Professor-Levin SirDocument30 pagesName-Amisha Choudhary Roll No. - 19/413 Class-3 Year 5 Sem Assignment-Factors That Led To French Revolution Professor-Levin SirRadhaNo ratings yet

- Power & The Reading Public: Ilana Feldmanhst 400VDocument24 pagesPower & The Reading Public: Ilana Feldmanhst 400Vapi-319766055No ratings yet

- IR AssignmentDocument8 pagesIR AssignmentNethmi vihangaNo ratings yet

- Q1Document8 pagesQ1Aishvarya MishraNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 18th Crisis Old Regime Enlightenment To PRINTDocument5 pagesUNIT 1 18th Crisis Old Regime Enlightenment To PRINTck8h74w8hbNo ratings yet

- Critical assessment of theories on British imperial expansionDocument9 pagesCritical assessment of theories on British imperial expansionKenny StevensonNo ratings yet

- Feudalism To CapitalismDocument2 pagesFeudalism To CapitalismRibuNo ratings yet

- AP Euro Absolutism in Western Europe 1589-1715Document16 pagesAP Euro Absolutism in Western Europe 1589-1715Billy bobNo ratings yet

- The French Revolution Primary Source AnalysisDocument26 pagesThe French Revolution Primary Source Analysisabdelkader_rhitNo ratings yet

- Evolving Trade in Rio de la PlataDocument16 pagesEvolving Trade in Rio de la PlataAriana SanchezNo ratings yet

- Modern Europe's Rise and Cultural EconomyDocument18 pagesModern Europe's Rise and Cultural EconomyGreenNo ratings yet

- Review of VaninaDocument36 pagesReview of VaninaNajaf HaiderNo ratings yet

- Late Merovingian France History and Hagiography by Paul Fouracre, Richard A. GerberdingDocument388 pagesLate Merovingian France History and Hagiography by Paul Fouracre, Richard A. GerberdingJoão Roberto RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Feudalism To CapitalismDocument4 pagesFeudalism To CapitalismAparupa RoyNo ratings yet

- The Origins and Results of the 1884-1885 Berlin ConferenceDocument12 pagesThe Origins and Results of the 1884-1885 Berlin ConferenceTyler100% (1)

- CULTURALESDocument8 pagesCULTURALESElvira López PalomaresNo ratings yet

- Peasants and King in Burgundy: Agrarian Foundations of French AbsolutismFrom EverandPeasants and King in Burgundy: Agrarian Foundations of French AbsolutismNo ratings yet

- 1unit 1 Crisis of The Ancient RegimeDocument40 pages1unit 1 Crisis of The Ancient RegimedonpapkaNo ratings yet

- Collins - State Building in Early-Modern Europe, The Case of FranceDocument32 pagesCollins - State Building in Early-Modern Europe, The Case of FranceMay VegaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Working Class in Shakespeare: DR - Asim ChatterjeeDocument5 pagesThe Rise of Working Class in Shakespeare: DR - Asim ChatterjeeinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Causes of French RevolutionDocument4 pagesCauses of French RevolutionShabnam BarshaNo ratings yet

- Unit 4. The 18th Century1Document16 pagesUnit 4. The 18th Century1Minh ChauNo ratings yet

- The History of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1815)From EverandThe History of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1815)No ratings yet

- Brandon Chan AP Euro Day 1+2: Background To The French RevolutionDocument3 pagesBrandon Chan AP Euro Day 1+2: Background To The French RevolutionJames WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Study GuideDocument6 pagesChapter 13 Study GuideMauricio PavanoNo ratings yet

- A Monarchy of Disseminated Courts. The Viceregal SystemaDocument12 pagesA Monarchy of Disseminated Courts. The Viceregal SystemaAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- The Witch Hunt As A Structure of ArgumentationDocument19 pagesThe Witch Hunt As A Structure of ArgumentationAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- ANDERSON. The Real Presence of Mary. Eucharistic Desbelief and The Limits of OrthodoxyDocument21 pagesANDERSON. The Real Presence of Mary. Eucharistic Desbelief and The Limits of OrthodoxyAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Codice Di Commercio 1882 - ItaliaDocument574 pagesCodice Di Commercio 1882 - ItaliaMarcelo Mardones Osorio100% (1)

- Battling Demons With Medical Authority. Werewolves, Physicians and RationalizationDocument16 pagesBattling Demons With Medical Authority. Werewolves, Physicians and RationalizationAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Witchcraft in England during the Civil WarDocument167 pagesWitchcraft in England during the Civil WarAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- A Revolution in Rights Reflections On The Democratic Invention of The Rights of ManDocument14 pagesA Revolution in Rights Reflections On The Democratic Invention of The Rights of ManAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Annihilation and DeiÞcation in BeguineDocument21 pagesAnnihilation and DeiÞcation in Beguinenicoleta5aldeaNo ratings yet

- Jacob's Well 1900Document349 pagesJacob's Well 1900Albert LanceNo ratings yet

- Absolutism and Class at The End of The Old Regime. The Case of LanguedocDocument29 pagesAbsolutism and Class at The End of The Old Regime. The Case of LanguedocAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Animals and ShamanismDocument133 pagesAnimals and ShamanismAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Actuality and Illusion in The Political Thought of MachiavelliDocument5 pagesActuality and Illusion in The Political Thought of MachiavelliAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Age of Absolutism. Capitalism and The Modern State SystemDocument24 pagesAge of Absolutism. Capitalism and The Modern State SystemAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Medievalia Ejemplo 1Document8 pagesMedievalia Ejemplo 1Albert LanceNo ratings yet

- Actuality and Illusion in The Political Thought of MachiavelliDocument5 pagesActuality and Illusion in The Political Thought of MachiavelliAlbert LanceNo ratings yet