Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Treatment Strategy According To The Status of Infection

Uploaded by

Handhika Dhio SumarsonoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Treatment Strategy According To The Status of Infection

Uploaded by

Handhika Dhio SumarsonoCopyright:

Available Formats

ANNALS OF SURGERY

Vol. 232, No. 5, 619 626

2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.

THIS MONTHS FEATURE

Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Treatment

Strategy According to the Status of Infection

Markus W. Buchler, MD, Beat Gloor, MD, Christophe A. Muller, MD, Helmut Friess, MD, Christian A. Seiler, MD, and

Waldemar Uhl, MD

From the Department of Visceral and Transplantation Surgery, University of Bern, Inselspital, Switzerland

Objective

To determine benefits of conservative versus surgical treatment in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis.

Summary Background Data

Infection of pancreatic necrosis is the most important risk factor contributing to death in severe acute pancreatitis, and it is

generally accepted that infected pancreatic necrosis should

be managed surgically. In contrast, the management of sterile

pancreatic necrosis accompanied by organ failure is controversial. Recent clinical experience has provided evidence that

conservative management of sterile pancreatic necrosis including early antibiotic administration seems promising.

Methods

A prospective single-center trial evaluated the role of nonsurgical management including early antibiotic treatment in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatic infection, if

confirmed by fine-needle aspiration, was considered an indication for surgery, whereas patients without signs of pancreatic infection were treated without surgery.

Results

Between January 1994 and June 1999, 204 consecutive patients with acute pancreatitis were recruited. Eighty-six (42%)

Necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) represents the severe form

of human acute pancreatitis.1,2 The past decade has seen a

considerable increase in our understanding and management

of NP. The natural course of severe acute pancreatitis

progresses in two phases. The first 14 days are characterized

by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome resulting

from the release of inflammatory mediators.3,4 In patients

Correspondence: Markus W. Buchler, MD, Dept. of Visceral and Transplantation Surgery, Inselspital, University of Bern, CH-3010 Bern,

Switzerland.

E-mail: markus.buechler@insel.ch

Accepted for publication February 23, 2000.

had necrotizing disease, of whom 57 (66%) had sterile and 29

(34%) infected necrosis. Patients with infected necrosis had

more organ failures and a greater extent of necrosis compared with those with sterile necrosis. When early antibiotic

treatment was used in all patients with necrotizing pancreatitis

(imipenem/cilastatin), the characteristics of pancreatic infection changed to predominantly gram-positive and fungal infections. Fine-needle aspiration showed a sensitivity of 96%

for detecting pancreatic infection. The death rate was 1.8%

(1/56) in patients with sterile necrosis managed without surgery versus 24% (7/29) in patients with infected necrosis

( P .01). Two patients whose infected necrosis could not be

diagnosed in a timely fashion died while receiving nonsurgical

treatment. Thus, an intent-to-treat analysis (nonsurgical vs.

surgical treatment) revealed a death rate of 5% (3/58) with

conservative management versus 21% (6/28) with surgery.

Conclusions

These results support nonsurgical management, including

early antibiotic treatment, in patients with sterile pancreatic

necrosis. Patients with infected necrosis still represent a highrisk group in severe acute pancreatitis, and for them surgical

treatment seems preferable.

with NP, organ failure is common and often occurs in the

absence of infection.5 In addition to organ dysfunction,

general derangements include hypovolemia, a hyperdynamic circulatory regulation,6 fluid loss from the intravascular space, and increased capillary permeability.7 The second phase, beginning approximately 2 weeks after the onset

of the disease, is dominated by sepsis-related complications

resulting from infection of pancreatic necrosis.8,9 This is

associated with multiple systemic complications, such as

pulmonary, renal, and cardiovascular failure. In the natural

course of the disease, infection of pancreatic necrosis occurs

in 40% to 70% of patients, and it has become the most

important risk factor of death from NP.10 12 Of patients

619

620

Buchler and Others

Table 1.

Ann. Surg. November 2000

DEFINITIONS USED TO DIAGNOSE ORGAN FAILURES

Organ System

Pulmonary insufficiency

Renal insufficiency

Cardiocirculatory dysfunction

Metabolic disorders

Sepsis:* Positive blood culture/aspirate and more

than one of these clinical signs

Definition of Organ Failure

Arterial PaO2 60 mmHg (despite 4 L O2/min via nasal tube) or need for mechanical

ventilation

Serum creatinine 250 mmol/L or need for hemofiltration or hemodialysis

Mean arterial pressure 70 mmHg or need for catecholamine support

Hyperglycemia 11 mmol/L

Hypocalcemia 2 mmol/L

Coagulation disorder (prothrombin time 70%; partial thromboplastin time 45 sec)

Rectal temperature 36 or 38C

Elevated heart rate 90/min

Tachypnea (respiratory rate 20/min) or hyperventilation (PaCO2 4.3 kPa)

White cell count 4 or 12.0 109/L or presence of 10% immature neutrophils

Hyperglycemia was not used as a criterion for metabolic disorder in patients with a history of diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance. Serum creatinine 250

mmol/L was not used as a criterion for renal failure in patients with a history of chronic renal insufficiency.

* Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus

Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992; 101(6):1644 1655.

who die of acute pancreatitis, more than two thirds of deaths

are due to late septic organ complications.1315

Antibiotic treatment with agents penetrating well into the

pancreas16 has been shown to prevent infection in severe

acute pancreatitis and to lower the death rate.1722 Still, the

general treatment principles in NP and particularly the role

of surgery are controversial issues. During the 1980s, according to our experience, 60% to 70% of patients with NP

were treated surgically.23 In 1991, Bradley and Allen24

introduced the concept of nonsurgical management of sterile necrosis, applying early antibiotic treatment. In 11 consecutive patients managed accordingly, there were no

deaths. In the same study, 27 patients with infected necrosis

were treated surgically using open packing, yielding a death

rate of 15%.

The promising concept of using infection as the main

parameter of surgical decision making has so far not been

adopted generally.25,26 Therefore, in a prospective singlecenter trial, we evaluated the role of nonsurgical treatment

in patients with sterile necrosis and surgical treatment in

patients with infected necrosis. In addition, we studied the

effect of early antibiotic treatment on the further course of

NP and its influence on the evolution and microbiologic

characteristics of the pancreatic infection.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between January 1994 and June 1999, 204 consecutive

patients with acute pancreatitis were recruited prospectively

from the Department of Visceral and Transplantation Surgery at the University of Bern. Inclusion criteria were an

elevation of serum amylase to more than three times the

upper normal limit and a typical clinical picture,27 including

abdominal pain.28 Patient stratification according to disease

severity was performed as previously published.29 NP was

defined as the appearance of pancreatic or extrapancreatic

necrosis30 on contrast-enhanced computed tomography

(CT) and a serum C-reactive protein value of more than 150

mg/L. CT was performed within 48 to 96 hours of admission and was repeated weekly in patients whose clinical

condition did not improve. On admission all patients were

treated medically according to generally accepted principles

consisting of withholding oral intake, providing pain relief,

and restoring fluid and electrolyte losses intravenously. If

vomiting had been a prominent part of the clinical picture,

a nasogastric tube was inserted. A proton pump inhibitor

was given to prevent stress ulcers, and low-molecularweight heparin (3,000 U/day) was given to prevent thrombosis. Pain treatment included the use of peridural anesthesia (n 99) or intravenous narcotic analgesics. Clinical

severity staging of acute pancreatitis was carried out using

the Ranson prognostic signs and the APACHE II scoring

system. Initially, patients were cared for in an intermediate

care unit or, in case of organ failure, in the intensive care

unit. In patients with NP, antibiotic treatment was given less

than 24 hours after CT findings of necrosis. We used imipenem/cilastatin (3 500 mg/day, intravenously) for 14

days according to the study protocol.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography was performed

in cases of biliary etiology, as proven by transcutaneous

ultrasonography and laboratory findings of cholestasis such as

elevated levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline

phosphatase, or bilirubin. Papillotomy was performed if stones

or sludge were present in the common bile duct.

In patients with NP, CT-guided fine-needle aspiration

(FNA) with consecutive Gram stain and bacteriologic culture was carried out if infection of necrosis was clinically

suspected. The indication for FNA was defined during the

course of NP in the following instances:

Newly developed signs of metabolic disorders and deterioration of organ failures of lung, kidney, or the

Treatment of Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Vol. 232 No. 5

Table 2.

621

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WITH EDEMATOUS PANCREATITIS (EP) AND

NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS (NP)

Female

Male

Mean age (range)

Biliary cause

Alcohol

Other or undefined cause

Mean serum c-reactive protein in mg/L (range)*

Mean Ranson score (range)

Mean APACHE II score (range)*

Mean hospital stay in days (range)

Hospital deaths

EP

(n 118)

NP

(n 86)

48 (41%)

70

54.2 (1796)

54 (46%)

36 (30%)

28 (24%)

81 (1205)

1.9 (07)

6.3 (116)

13 (253)

0

31 (36%)

55

56.6 (2887)

38 (44%)

32 (37%)

16 (19%)

228 (101456)

3.9 (08)

12.6 (528)

44.1 (11209)

9 (10%)

NS

.00001

.005

.01

.0001

.0012

* Peak value in the first week of disease.

cardiocirculatory system (for the definition of organ

failure, see Table 1)

Newly developed increase in blood leukocytes or fever

(38.5C) after initial response to conservative treatment.

Infection of pancreatic necrosis as proven by FNA was

regarded as an indication for surgical treatment and resulted

in surgical intervention (necrosectomy and continuous postoperative lavage of the necrotic cavities) within 24 hours.

During surgery, at least two smears for bacteriologic culture

were taken from the pancreatic necrosis and from the adjacent necrotic cavities in the retroperitoneum. Postoperative

antibiotic treatment, including antimycotic treatment, was

adapted according to the bacteriologic findings and microbiologic testing of resistance.

A complete follow-up was carried out (mean follow-up

time 35 months) after hospital discharge to determine late

consequences of edematous pancreatitis and sterile and infected pancreatic necrosis.

Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney or chisquare test where appropriate. P .05 was considered

significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. There

were 204 patients in the study, 125 (61%) men and 79

(39%) women. Mean age was 55.1 years (range 1796). The

cause was biliary in 92 (45%) patients, alcohol overindulgence in 68 (33%), and other or undefined in 44 (22%).

According to CT and C-reactive protein findings, there were

118 (58%) and 86 (42%) patients with edematous pancreatitis and NP, respectively.

Edematous Pancreatitis

In 118 patients, pancreatic necrosis was ruled out by CT

findings and C-reactive protein serum levels. Fifty-six pa-

tients stayed for a mean of 2.3 days (range 17) in intermediate care. No patient with edematous pancreatitis had

multiple organ failure, but in 12 patients (10%) single organ

failure was diagnosed (1 renal, 4 pulmonary insufficiency, 3

cardiocirculatory insufficiency, 4 metabolic disorders). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed early (in the first 24 48 hours) in 54 patients with

biliary etiology, and papillotomy and stone retrieval were

performed in 38 of those patients. In addition, endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography was carried out before

hospital discharge in 31 patients with an unknown cause and

to exclude tumor-induced acute pancreatitis. Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy was done in 35 patients a median of 8.6

days after admission (range 219), and open cholecystectomy was performed in 19 patients a median of 9 days after

admission (range 219). There were no hospital deaths, and

the mean hospital stay was 13 days (range 253).

Follow-Up

Hospital readmission occurred in seven patients (6%)

after a mean of 8.3 months for the following reasons:

recurrent acute pancreatitis (n 4), duodenal obstruction

(n 1), and pancreatic pseudocyst (n 1).

Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Eighty-six patients were staged as having NP based on

CT findings and C-reactive protein levels. The mean Ranson score was 3.9 (range 0 8) and APACHE II scoring was

12.6 (range 528) (P .01 vs. edematous pancreatitis) (see

Table 2). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography was carried out in 58 patients, and papillotomy and stone removal

were performed in 20 of those patients. Again, endoscopy

was performed in the first 24 to 48 hours in 38 patients with

biliary etiology and later in 20 patients with a cause other

than gallstones. Single and multiple organ failure occurred

622

Buchler and Others

Ann. Surg. November 2000

Table 3.

ORGAN FAILURE IN PATIENTS WITH PANCREATITIS

Necrotizing Pancreatitis (n 86)

Acute Pancreatitis

No. of patients with organ failures

No. of patients with single organ failure

No. of patients with multiple organ failure

Pulmonary insufficiency

Renal insufficiency

Cardiocirculatory insufficiency

Metabolic disorders

Sepsis

EP

(n 118)

NP

(n 86)

SPN

(n 57)

IPN

(n 29)

12 (10%)

12 (10%)

0

4 (3%)

1 (1%)

3 (3%)

4 (3%)

0

62 (72%)

32 (37%)

30 (35%)

54 (63%)

11 (13%)

20 (23%)

22 (26%)

9 (10%)

.00001

.00001

.00001

.00001

.0017

.00001

.00001

.006

35 (61%)

25 (44%)

10 (18%)

27 (47%)

3 (5%)

5 (9%)

13 (23%)

1 (2%)

27 (93%)

7 (24%)

20 (69%)

27 (93%)

8 (28%)

15 (52%)

9 (31%)

8 (28%)

.015

NS

.00001

.00001

.01

.00001

NS

.01

EP, edematous pancreatitis; IPN, infected pancreatic necrosis; NP, necrotizing pancreatitis; SPN, sterile pancreatic necrosis.

in 32 and 30 patients, respectively (P .00001 vs. edematous pancreatitis) (Table 3).

Sterile Necrosis

Data on gender, age, cause, C-reactive protein levels,

Ranson score, APACHE II score, length of hospital stay,

and hospital death rate are given in Table 4. The severity,

based on the Ranson and APACHE II scores in the first

week of the disease, was similar between sterile and infected necrosis. However, necrosis was considerably more

extended in patients with infected necrosis (Table 5).

In the group with sterile necrosis, 56/57 patients were

managed conservatively. In a woman with chronic lymphatic leukemia and sterile necrosis and early multiple

organ failure (renal, pulmonary, cardiocirculatory, and metabolic), the study protocol was violated despite a negative

FNA because of severe, rapid deterioration while receiving

Table 4.

intensive care treatment. Surgical necrosectomy was carried

out on day 11 after onset of symptoms. Intraoperative cultures were negative. After surgery, renal function and respiratory parameters improved. On day 18 an infection with

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Candida

albicans occurred, and the patient died on day 25 of septic

multiple organ failure. Of the 56 patients managed conservatively, one patient with severe chronic alcohol disease

died on day 13 of severe respiratory distress syndrome, not

responding to resuscitation. Autopsy revealed massive necrosis retroperitoneally and severe diffuse lung injury. The

death rate in patients with sterile necrosis managed without

surgery was therefore 1.8% (1/56).

Fifteen patients (15/57; 26%) fulfilled the criteria for

FNA. In these patients, 18 FNAs were performed, showing

negative Gram stain as well as negative culture results

(Table 6). The first FNA in these patients was performed on

day 12 (range 4 22) after onset of symptoms.

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WITH STERILE AND INFECTED NECROSIS

Female

Male

Mean age (range)

Biliary cause

Alcohol

Other or undefined cause

Mean serum c-reactive protein in mg/L (range)*

Mean Ranson score (range)

Mean APACHE II score (range)*

Mean hospital stay in days (range)

Surgical treatment (%)

Hospital deaths

IPN, infected pancreatic necrosis; SPN, sterile pancreatic necrosis.

* Peak value in the first week of disease.

SPN

(n 57)

IPN

(n 29)

20

37

56.1 (2887)

22 (39%)

23

12

222 (112343)

3.8 (08)

12.2 (528)

23.5 (1185)

1 (2%)

2 (3.5%)

11

18

57.6 (2975)

16 (55%)

9

4

231 (101456)

4.2 (07)

13.2 (622)

84.8 (22209)

27 (93%)

7 (24%)

NS

NS

NS

NS

.001

.0001

.01

Treatment of Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Vol. 232 No. 5

Table 5. MAXIMUM EXTENT OF

NECROSIS ACCORDING TO COMPUTED

TOMOGRAPHY FINDINGS

Extent of Necrosis

30% of the pancreas

3050% of the pancreas

50% of the pancreas

623

Table 7. TREATMENT RESULTS IN

PATIENTS WITH INFECTED NECROSIS

AND SURGICAL TREATMENT (n 27)

SPN

(n 57)

IPN

(n 29)

32 (56%)

16 (28%)

9 (16%)

3 (10%)

3 (10%)

23 (80%)

.00001

NS

.00001

IPN, infected pancreatic necrosis; SPN, sterile pancreatic necrosis.

Time of onset of pain until infection in days

Day of first surgical intervention

Duration of lavage (days)

Reoperation

Additional interventional procedure

Complications

Bleeding

Pancreatic fistula

Burst abdomen

Pseudocyst

20.8 (1048)

21.7 (1049)

37.6 (10124)

6 (22%)

3 (11%)

12 (44%)

2 (7%)

8 (29%)

1 (4%)

1 (4%)

Follow-Up

Values are mean and range or number of patients percentage.

During the study period, 11 patients (19%) were readmitted to the hospital after a mean of 6.9 months for various

pancreatitis-related complications such as recurrent pancreatitis (n 4), pancreatic pseudocyst (n 4), duodenal

obstruction (n 2), and splenic vein thrombosis (n 1).

One patient initially classified as and treated for sterile

necrosis was now found to suffer from infected necrosis.

This patient was readmitted after being at home for 14 days

and subsequently underwent necrosectomy and postoperative lavage of the retroperitoneal cavity. The patient recovered after the second hospital admission. In four patients a

pseudocyst was treated with a cystojejunostomy after a

mean of 4.25 months (range 2 6). In none of them was the

pseudocyst infected.

Of eight monocultures diagnosed in the preoperative FNA,

seven were confirmed by intraoperative cultures. In the

eighth, intraoperative culture results showed a polymicrobial infection. The result of 18 polymicrobial infections

found by FNA was confirmed in 17 by intraoperative cultures. In the remaining one, intraoperative culture revealed

gram-negative infection only. Thus, 92% (24/26) of the

FNA findings were correct with regard to the microbiologic

differentiation. Overall, 27 of 28 patients (96%) were correctly diagnosed as having infected necrosis.

Infected Necrosis

FNA Results

In 27 patients with NP, preoperative CT-guided FNA

revealed infected pancreatic necrosis. The first FNA was

performed a mean of 17 days (range 3 48) after onset of

symptoms. In one patient with infected necrosis, contrastenhanced CT demonstrated air in the necrotic areas, indicating infection. This patient underwent surgery without a

prior FNA. In another patient who subsequently died, FNA

was negative despite pancreatic infection, and the patient

was managed conservatively. In 26 patients both preoperative FNA and intraoperative culture results were available.

Table 6. PATIENTS UNDERGOING SINGLE

OR MULTIPLE FINE-NEEDLE

ASPIRATIONS

Number of

Aspirations

Sterile Necrosis

(15 patients)

Infected Necrosis

(28 patients)

1

2

3

3

12

3

0

0

16

6

5

1

Surgical Treatment

A total of 27 patients with infected necrosis underwent

necrosectomy and subsequent continuous lavage of the necrotic cavity by means of double-lumen drainage tubes.23

Treatment parameters of these patients are outlined in Table

7 and bacteriologic results are summarized in Table 8. There

were 18 patients with polymicrobial and 10 patients with

monomicrobial infection. Different fungus species were

found in eight patients (29%), or 17% of all positive cultures. In one patient with rapidly progressing multiple organ

Table 8. BACTERIOLOGIC FINDINGS IN

28 PATIENTS WITH INFECTED NECROSIS

Germ

Number of positive cultures (n

47) (% of all positive cultures)

Staphylococcus spp.

Candida

Enterococcus

Escherichia coli

Klebsiella spp.

Streptococcus spp.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Morganella morgani

Bacteroides fragilis

17 (36%)

8 (17%)

6 (13%)

5 (11%)

4 (9%)

3 (6%)

2 (4%)

1 (2%)

1 (2%)

Intraoperative culture results of 27 patients undergoing surgery and fine-needle

aspiration result from one patient who had a fine-needle aspiration only.

624

Buchler and Others

failure, infection was proven by FNA on day 15, but the

patient died that same day before surgery was performed.

Another patient who had three FNAs with negative results

responded to intensive care unit treatment and conservative

management. Back on a regular ward, he suddenly was

found dead in his bed. Autopsy revealed multiple septic

pulmonary emboli and infected pancreatic necrosis. Thus,

only 27 of 29 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis

underwent surgery.

The death rate in patients with infected necrosis was 24%

(7/29). Causes of death were nonresponding multiple organ

failure (n 4), myocardial infarction/insufficiency (n 2),

and multiple septic pulmonary emboli (n 1).

Follow-Up

During the study period, seven patients (32%) were readmitted to the hospital after a mean of 4 months (range

1.5 6) for various pancreatitis-related complications: persistent pancreatic fistula (n 3), recurrent pancreatitis (n

1), pancreatic pseudocyst (n 1), pancreatic abscess (n

1), and chronic pain (n 1). The patient with the abscess

was successfully treated by a percutaneous drainage procedure. Two of the patients readmitted because of a fistula

were managed conservatively; one patient was treated surgically. The pancreatic pseudocyst was surgically drained

with a cystojejunostomy. All seven patients recovered and

were discharged home.

Intent-to-Treat Analysis

Analysis of the patients in an intent-to-treat manner (nonsurgical vs. surgical treatment) showed that 3/58 (5%) died

while receiving conservative management (1 patient with

sterile necrosis, 2 patients with infected necrosis) and 6/28

(21%) died after surgery (5 with infected necrosis, 1 with

sterile necrosis) (P .05). This intent-to-treat analysis

seems necessary because in the patients whose NP was

managed without surgery, two died in whom infection of

necrosis was not diagnosed in a timely fashion.

DISCUSSION

The concept of conservative treatment of severe acute

pancreatitis originates from several sources. First, we

learned that an episode of severe acute pancreatitis

progresses in two phases. The first 10 to 14 days are

characterized by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome maintained by the release of various inflammatory

mediators.3,4 The production of such mediators in large

amounts may lead to distant organ failure, and surgery does

not seem to be the appropriate intervention at that stage of

the disease. Second, intensive care treatment has improved

significantly during the past decade, and patients with severe acute pancreatitis are best managed there.31 Third,

septic complications in the second phase of the disease can

be reduced and delayed by using appropriate antibiot-

Ann. Surg. November 2000

ics.16,21,22,32 Fourth, one previous study provided evidence

that conservative management is feasible in patients with

sterile necrosis.24

Our study demonstrates and confirms that conservative

treatment of sterile necrosis using early antibiotics is safe

and effective. Of 56 patients with sterile NP managed without surgery, 1 patient died of severe respiratory distress

syndrome. Recent prospective controlled trials have demonstrated that the prevalence of pancreatic infection in NP

could be lowered significantly to 10% to 43% if antibiotics

with proven efficacy in acute pancreatitis were given early.17,19,33 Our trial supports this by showing an infection

rate of 34% in NP, which is lower than the prevalence data

of up to 70% from the 1980s observed in patients not

receiving antibiotic treatment prophylactically.8,34,35 Pancreatic infection is regarded as the main risk factor for death

in patients with acute pancreatitis,9 and preventing this risk

factor seems to represent a major step forward in the management of NP. This statement is further supported by the

data from several contemporary randomized studies that

have been subjected to meta-analysis, showing an improvement in outcome associated with antibiotic treatment.21,22,32

Consequently, a significant body of clinicians use antibiotic

prophylaxis in the initial treatment of patients with predicted severe disease.36 Ruling out infection in NP and

thereby preventing surgical measures, which are still standard approaches for infected necrosis, might reduce hospital

expenses considerably in the future. Data from other groups

argue for surgical treatment in sterile necrosis, particularly

in patients with ongoing multiple organ failure or local

complications such as an inflammatory enlargement of the

pancreas causing obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract or

common bile duct.25,26 Our trial demonstrates that 33 of 35

patients with sterile necrosis and organ failure responded

well to intensive care treatment including mechanical ventilation, catecholamine treatment for cardiocirculatory failure, and hemodialysis for renal failure. However, in our

series one patient with early multiple organ failure not

responding to intensive care died after surgical necrosectomy for sterile necrosis. It can be presumed that if antibiotic treatment is successful in preventing infection, surgery

in NP might not be able to achieve a better goal than

conservative treatment. Thus, in the event of rapidly progressing multiple organ failure in sterile necrosis, surgical

measures might not overcome this problem, just as conservative treatment does not in the rare cases of so-called

fulminant pancreatitis.37

In our study, severity staging showed no differences

between patients with sterile and infected necrosis. This

finding may be explained by the fact that Ranson and

APACHE II scores were obtained during the first week of

the disease process. The Ranson criteria, by definition, are

recorded in the initial 48 hours. The APACHE II score was

calculated daily and the maximum score in the first week

was taken for statistical analysis. However, infection of

peripancreatic or pancreatic necrosis was diagnosed after a

Vol. 232 No. 5

mean of 21 days. It seems likely that this is why patients

with infected necrosis, despite the initially documented

equal severity of disease, stayed considerably longer in the

hospital and had more organ failures that occurred after the

first week in the hospital. Others have reported similar

results,1 but some have not.5

The reason for the difference in the prevalence of organ

failure, especially in the subgroup of patients with sterile

necrosis, might arise from different criteria for classifying

patients and defining organ failure. Also, in patients with

infected necrosis, contrast-enhanced CT revealed more patients with extended necrosis compared with those with

sterile necrosis. It cannot be determined from our trial

whether our result (i.e., more extensive necrosis in the

patients with infected necrosis) is the cause of the occurrence of infection or whether infection is the cause of the

extended necrosis. Several authors consider extended necrosis (i.e., necrosis of 50% of the pancreas) to be a risk

factor for infection.2,23,38,39 A recent paper demonstrated

that in patients with sterile necrosis, the extent of necrosis

correlated with the frequency of organ failure, whereas

infected necrosis was associated with organ failure irrespective of the extent of necrosis,1 supporting the concept that

infection is the major determinant for the outcome.

The present death rate of 10% in patients with NP closely

parallels the one described by Branum et al,40 who described

50 patients with NP treated with surgery; 12% of them died.

Similar to the results of Bradley and Allen,24 we found a higher

death rate in patients with infected necrosis. However, in two

patients with infected necrosis who ultimately died, the infection was not diagnosed in time and therefore no surgery was

performed. In an intent-to-treat analysis, these deaths were

shifted to the patients with sterile necrosis, thereby rendering

insignificant the difference in death rate between patients with

infected and sterile necrosis.

In this series patients with sterile necrosis were discharged home after a mean of 23.5 days; only three patients

stayed longer than 2 months (see Table 4). None of these

three was readmitted to the hospital for persistent pain or

pancreatitis. According to a recent report,41 it might be

possible that return to work in these patients could be

hastened by performing surgery at 4 weeks if the patient

remains symptomatic.

A second major finding of our trial was that early antibiotic treatment of NP changes the spectrum of bacteria in

patients in whom infection develops. Bacterial translocation

from the gut has been demonstrated to be the main cause of

infection in NP.42 45 Therefore, the bacterial spectrum of

infection has been described as primarily gram-negative and

in part anaerobic. After we administered antibiotics with a

dominant efficacy against gram-negative germs and anaerobes (imipenem/cilastatin), the bacteria in more than half of

our patients with pancreatic infection were found to be

gram-positive. In addition, we found eight patients (29%)

infected with fungus. In a series of 57 patients with NP,

Grewe et al46 described 7 (12%) with fungal infection.

Treatment of Necrotizing Pancreatitis

625

These patients were treated with a mean of four different

antibiotics for a mean of 23 days. Such findings raise the

question of the duration of primary antibiotic treatment (14

days in our trial) and of the need to use agents effective

against gram-positive bacteria and fungi concomitantly or

consecutively. In addition, it is likely that these secondary

infections do not originate in the gut but rather are hospitalacquired, entering the pancreas by means of hematogenous

routes from venous or urinary catheters, tracheal tubes, and

so forth. This argument of nosocomial infection is supported by the time when infection occurred in our trial (later

than 20 days); in earlier studies, approximately 40% of

infections with gram-negative germs occurred within 2

weeks after admission.8,17,19,47 The question of additional

primary or secondary anti gram-positive and antifungal

treatments in NP must be addressed in future clinical trials.

Surgery remains the gold standard in the treatment of

infected pancreatic necrosis,48 and necrosectomy and continuous closed lavage was successful in 67% of our patients

with infected necrosis. However, 22% needed a secondary

intervention and 11% an additional interventional procedure, and the complication rate was 44%. Fernandez-del

Castillo et al41 recently described 64 patients treated surgically and found a single surgical procedure to be sufficient

in 69%. In the present study, infection of necrotic tissue

occurred a mean of 21 days after onset of the disease, and

surgery was performed during the 24 hours after its diagnosis. More than 3 weeks after the onset of the disease, the

demarcation between viable and necrotic tissue is easier to

assess than earlier in the disease process. This approach

decreases the bleeding risk and minimizes the surgeryrelated loss of vital tissue leading to surgery-induced endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.49 The same

policy of delaying surgery until demarcation of pancreatic

necrosis is far advanced has been reported by others.41

Recently, considerable interest has been generated in the

nonsurgical management of infected necrosis using truly conservative or interventional measures. Single-center reports in

so far small patient groups have demonstrated that even in

infected necrosis, some patients recover with nonsurgical management.50 It is important to differentiate between infected

necrosis and pancreatic abscess, a condition that has been

shown to respond to interventional treatment.51 Nevertheless,

there might be patients with infected necrosis without multiple

organ failure who would respond to nonsurgical measures

including antibiotics, and future trials need to define this population. To extend this argument, at least from a theoretical

point of view it might be possible that in our group of patients

classified as having sterile necrosis, some might have been

infected and did not undergo FNA because of a silent clinical

course, responding well to conservative management. Indeed,

one patient originally classified as having sterile necrosis was

readmitted to the hospital with infected necrosis 14 days after

the primary discharge.

In summary, the data from our study support the concept of

using conservative treatment for sterile NP versus surgery for

626

Buchler and Others

infected necrosis, an approach that could improve the clinical

success rate in NP in terms of the death rate of the past.

References

1. Isenmann R, Rau B, Beger HG. Bacterial infection and extent of

necrosis are determinants of organ failure in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1999; 86:1020 1024.

2. Reber HA, McFadden DW. Indications for surgery in necrotizing

pancreatitis. West J Med 1993; 159(6):704 707.

3. Norman J. The role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1998; 175(1):76 83.

4. Gloor B, Reber HA. Effects of cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators on human acute pancreatitis. J Int Care Med 1998; 13(6):305312.

5. Tenner S, Sica G, Hughes M, et al. Relationship of necrosis to organ failure

in severe acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1997; 113(3):899903.

6. Beger HG, Bittner R, Buchler M, et al. Hemodynamic data pattern in

patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1986; 90(1):74 79.

7. Knoefel WT, Kollias N, Warshaw AL, et al. Pancreatic microcirculatory changes in experimental pancreatitis of graded severity in the rat.

Surgery 1994; 116(5):904 913.

8. Beger HG, Bittner R, Block S, Buchler M. Bacterial contamination of

pancreatic necrosis. A prospective clinical study. Gastroenterology

1986; 91(2):433 438.

9. Uhl W, Schrag HJ, Wheatley AM, Buchler MW. The role of infection

in acute pancreatitis. Dig Surg 1994; 11:214 219.

10. Gerzof SG, Banks PA, Robbins AH, et al. Early diagnosis of pancreatic infection by computed tomography-guided aspiration. Gastroenterology 1987; 93(6):13151320.

11. Beger HG, Rau B, Mayer J, Pralle U. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg 1997; 21(2):130 135.

12. Bassi C, Falconi M, Girelli F, et al. Microbiological findings in severe

pancreatitis. Surg Res Comm 1989; 5:1 4.

13. Bradley EL. Antibiotics in acute pancreatitis. Current status and future

directions. Am J Surg 1989; 158(5):472 477.

14. Buchler M, Uhl W, Beger HG. Complications of acute pancreatitis and

their management. Curr Opin Gen Surg 1993:282286.

15. Schmid SW, Uhl W, Friess H, et al. The role of infection in acute

pancreatitis. Gut 1999; 45(2):311.

16. Buchler M, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, et al. Human pancreatic tissue

concentration of bactericidal antibiotics. Gastroenterology 1992;

103(6):19021908.

17. Luiten EJ, Hop WC, Lange JF, Bruining HA. Controlled clinical trial

of selective decontamination for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg 1995; 222(1):57 65.

18. Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Vesentini S, Campedelli A. A randomized

multicenter clinical trial of antibiotic prophylaxis of septic complications in acute necrotizing pancreatitis with imipenem. Surg Gynecol

Obstet 1993; 176(5):480 483.

19. Sainio V, Kemppainen E, Puolakkainen P, et al. Early antibiotic treatment

in acute necrotising pancreatitis. Lancet 1995; 346(8976):663 667.

20. Schwarz M, Isenmann R, Meyer H, Beger HG. [Antibiotic use in

necrotizing pancreatitis. Results of a controlled study]. Dtsch Med

Wochenschr 1997; 122(12):356 361.

21. Powell J, Miles R, Siriwardena A. Antibiotic prophylaxis in the initial

management of severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1998; 85:582587.

22. Golub R, Siddiqi F, Pohl D. Role of antibiotics in acute pancreatitis: a

meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2:496 503.

23. Beger HG, Buchler M, Bittner R, et al. Necrosectomy and postoperative local lavage in necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1988; 75(3):

207212.

24. Bradley EL, Allen K. A prospective longitudinal study of observation

versus surgical intervention in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1991; 161(1):19 25.

25. Rau B, Pralle U, Uhl W, et al. Management of sterile necrosis in

instances of severe acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 181(4):

279 288.

Ann. Surg. November 2000

26. Rattner DW, Legermate DA, Lee MJ, et al. Surgical debridement of

symptomatic pancreatic necrosis is beneficial irrespective of infection.

Am J Surg 1992; 163:105110.

27. Levitt MD, Eckfeldt JH. Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In: Go VLW,

Dimagno EP, Gardner JD, et al, eds. The Pancreas: Biology, Pathobiology, and Disease. New York: Raven Press; 1993:613 635.

28. Uhl W, Buchler MW, Malfertheiner P, et al. A randomized, doubleblind, multicenter trial of octreotide in moderate to severe acute

pancreatitis. Gut 1999; 45:97104.

29. Buchler M, Malfertheiner P, Uhl W, et al. Gabexate mesylate in human

acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1993; 104:11651170.

30. Sakorafas GH, Tsiotos GG, Sarr MG. Extrapancreatic necrotizing

pancreatitis with viable pancreas: a previously underappreciated entity.

J Am Coll Surg 1999; 188(6):643 648.

31. Sigurdsson GH. Intensive care management of acute pancreatitis. Dig

Surg 1994; 11:231241.

32. Wyncoll D. The management of severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis:

an evidence-based review of the literature. Intensive Care Med 1999;

25:146 156.

33. Bassi C, Falconi M, Talamini G, et al. Controlled clinical trial of

pefloxacin versus imipenem in severe acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1998; 115:15131517.

34. Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Surgical intervention in acute pancreatitis.

Crit Care Med 1988; 16(1):89 95.

35. Frey CF, Bradley EL, Beger HG. Progress in acute pancreatitis. Surg

Gynecol Obstet 1988; 167(4):282286.

36. Powell JJ, Campbell E, Johnson CD, Siriwardena AK. Survey of

antibiotic prophylaxis in acute pancreatitis in the UK and Ireland. Br J

Surg 1999; 86(3):320 322.

37. Farthmann EH, Lausen M, Schoffel U. Indications for surgical treatment of

acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 1993; 40(6):556562.

38. Reber HA, Truman HS. Surgical intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1986; 91:479 481.

39. McFadden DW, Reber HA. Indications for surgery in severe acute

pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol 1994; 15(2):8390.

40. Branum G, Galloway J, Hirchowitz W, et al. Pancreatic necrosis:

results of necrosectomy, packing, and ultimate closure over drains.

Ann Surg 1998; 227:870 877.

41. Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Makary MA, et al. Debridement and closed packing for the treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis.

Ann Surg 1998; 228:676 684.

42. Moody FG, Haley-Russell D, Muncy DM. Intestinal transit and bacterial translocation in obstructive pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;

40:1798 1804.

43. Runkel NS, Moody FG, Smith GS, et al. The role of the gut in the development of sepsis in acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res 1991; 51(1):1823.

44. Widdison AL, Karanjia ND, Reber HA. Routes of spread of pathogens

into the pancreas in a feline model of acute pancreatitis. Gut 1994;

35:1306 1310.

45. Widdison AL, Alvarez C, Chang YB, et al. Sources of pancreatic

pathogens in acute pancreatitis in cats. Pancreas 1994; 9:536 541.

46. Grewe M, Tsiotos GG, Luque de-Leon E, Sarr MG. Fungal infection

in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 188:408 414.

47. Beger HG. Surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis. Surg Clin

North Am 1989; 69:529 549.

48. Gloor B, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Changing concepts in the surgical

management of acute pancreatitis. Baillie`res Clin Gastroenterol 1999;

13:303315.

49. Aultman DF, Bilton BD, Zibari GB, et al. Nonoperative therapy for

acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Am Surg 1997; 63:1114 1117.

50. Freeny PC, Hauptmann E, Althaus SJ, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided

catheter drainage of infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis: techniques

and results. Am J Roentgenol 1998; 170(4):969 975.

51. Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1993; 128:586 590.

You might also like

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyFrom EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Clinical Pancreatology: For Practising Gastroenterologists and SurgeonsFrom EverandClinical Pancreatology: For Practising Gastroenterologists and SurgeonsJuan Enrique Dominguez-MunozNo ratings yet

- Clinical-Liver, Pancreas, and Biliary TractDocument8 pagesClinical-Liver, Pancreas, and Biliary TractKirsten HartmanNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionDocument7 pagesPancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionNicolas RuizNo ratings yet

- General Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueDocument3 pagesGeneral Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueRahul SinghNo ratings yet

- Liver, Pancreas and Biliary Tract Problems: Research JournalDocument13 pagesLiver, Pancreas and Biliary Tract Problems: Research JournalElaine Frances IlloNo ratings yet

- Impact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyDocument10 pagesImpact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyPutri PadmosuwarnoNo ratings yet

- Management of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis 65Document4 pagesManagement of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis 65zahir_jasNo ratings yet

- Systematized Management of Postoperative Enterocutaneous Fistulas. A 14 Years ExperienceDocument5 pagesSystematized Management of Postoperative Enterocutaneous Fistulas. A 14 Years ExperienceYacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- Effect of Antibiotic Prophylaxis On Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Results of A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesEffect of Antibiotic Prophylaxis On Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Results of A Randomized Controlled TrialKirsten HartmanNo ratings yet

- 72-Manuscript Word File (STEP 1) - 98-3-10-20180605Document5 pages72-Manuscript Word File (STEP 1) - 98-3-10-20180605Hamza AhmedNo ratings yet

- Early Use of TIPS in Cirrhosis and Variceal BleedingDocument10 pagesEarly Use of TIPS in Cirrhosis and Variceal Bleedingray liNo ratings yet

- Song 2017Document8 pagesSong 2017Patricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Research Article Challenges Encountered During The Treatment of Acute Mesenteric IschemiaDocument9 pagesResearch Article Challenges Encountered During The Treatment of Acute Mesenteric IschemiaDyah RendyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Proper Treatment of Renal Abscesses Remains A Challenge For PhysiciansDocument6 pagesDiagnosis and Proper Treatment of Renal Abscesses Remains A Challenge For PhysiciansDevraj ChoudhariNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Sepsis Prognostic FactorDocument6 pagesAbdominal Sepsis Prognostic FactorPrasojo JojoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal: Acute PancreatitisDocument11 pagesJurnal: Acute Pancreatitisahmad fachryNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DhaDocument11 pagesJurnal DhasiydahNo ratings yet

- Indicación RelaparotomiaDocument6 pagesIndicación RelaparotomiaJohnHarvardNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults ManagementDocument16 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults ManagementPriscila Tobar AlcántarNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in AdultsDocument19 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adultsdimi firmatoNo ratings yet

- Colitis Induced ChemotherapyDocument11 pagesColitis Induced Chemotherapyhandris yanitraNo ratings yet

- EchografyDocument6 pagesEchografyMiha ElaNo ratings yet

- Early Ercp and Papillotomy Compared With Conservative Treatment For Acute Biliary PancreatitisDocument6 pagesEarly Ercp and Papillotomy Compared With Conservative Treatment For Acute Biliary PancreatitisRT_BokNo ratings yet

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2013 BARON 354 9Document6 pagesCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2013 BARON 354 9Stephanie PlascenciaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ebn PerikarditisDocument13 pagesJurnal Ebn Perikarditistino prima dito100% (1)

- Analysis of Antibiotics Selection in Patients Undergoing Appendectomy in A Chinese Tertiary Care HospitalDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Antibiotics Selection in Patients Undergoing Appendectomy in A Chinese Tertiary Care HospitalYuanico LiraukaNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Versus Early EndosDocument5 pagesManagement of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Versus Early EndossamuelNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Versus Early EndosDocument5 pagesManagement of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Versus Early EndosCarolina Ormaza GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Elterman 2014Document3 pagesElterman 2014Ana Luisa DantasNo ratings yet

- Early Management of Acute Pancreatitis-A Review of The Best Evidence. Dig Liver Dis 2017Document32 pagesEarly Management of Acute Pancreatitis-A Review of The Best Evidence. Dig Liver Dis 2017América FloresNo ratings yet

- PimpaleDocument6 pagesPimpaleMariano BritoNo ratings yet

- Modern Management of Pyogenic Hepatic Abscess: A Case Series and Review of The LiteratureDocument8 pagesModern Management of Pyogenic Hepatic Abscess: A Case Series and Review of The LiteratureAstari Pratiwi NuhrintamaNo ratings yet

- Acute Pyelonephritis in Adults: A Case Series of 223 PatientsDocument6 pagesAcute Pyelonephritis in Adults: A Case Series of 223 PatientsshiaNo ratings yet

- Liver A BSC DrainDocument8 pagesLiver A BSC DrainAngelica AmesquitaNo ratings yet

- Apendisitis MRM 3Document8 pagesApendisitis MRM 3siti solikhaNo ratings yet

- (The Clinics - Surgery) Steve Behrman MD FACS, Ron Martin MD FACS - Modern Concepts in Pancreatic Surgery, An Issue of Surgical Clinics, 1e (2013, Elsevier)Document197 pages(The Clinics - Surgery) Steve Behrman MD FACS, Ron Martin MD FACS - Modern Concepts in Pancreatic Surgery, An Issue of Surgical Clinics, 1e (2013, Elsevier)Yee Wei HoongNo ratings yet

- Organ-Specific InfectionsDocument4 pagesOrgan-Specific InfectionsMin dela FuenteNo ratings yet

- 260-Article Text-875-1-10-20220728Document4 pages260-Article Text-875-1-10-20220728hasan andrianNo ratings yet

- US en EndometritisDocument7 pagesUS en EndometritisRubí FuerteNo ratings yet

- Management of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis: State of The ArtDocument9 pagesManagement of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis: State of The ArtSares DaselvaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S001650850862925X MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S001650850862925X MainMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- Outcome and Clinical Characteristics in Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective StudyDocument7 pagesOutcome and Clinical Characteristics in Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective StudylestarisurabayaNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Acute Pancreatitis SurgeryDocument17 pagesJournal Reading Acute Pancreatitis Surgeryimanda rahmatNo ratings yet

- Appropriate Antibiotics For Peritonsillar Abscess - A 9 Month CohortDocument5 pagesAppropriate Antibiotics For Peritonsillar Abscess - A 9 Month CohortSiti Annisa NurfathiaNo ratings yet

- PylonefritisDocument8 pagesPylonefritissintaNo ratings yet

- Cholelithiasis: Causative Factors, Clinical Manifestations and ManagementDocument6 pagesCholelithiasis: Causative Factors, Clinical Manifestations and ManagementmusdalifahNo ratings yet

- Wja 3 1Document12 pagesWja 3 1Atuy NapsterNo ratings yet

- Cholangitis: Causes, Diagnosis, and ManagementDocument10 pagesCholangitis: Causes, Diagnosis, and ManagementDianaNo ratings yet

- Manejo Del ResangradoDocument13 pagesManejo Del ResangradoRudy J CoradoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Episodes of Hypoglycemia Secondary To An Insulinoma Case ReportDocument4 pagesMultiple Episodes of Hypoglycemia Secondary To An Insulinoma Case ReportmiguelNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument3 pages1 PBMartynaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofPablo BarraganNo ratings yet

- Critical Apprisal of A Prospective StudyDocument7 pagesCritical Apprisal of A Prospective StudyVK LabasanNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Outcomes and Predictive Factors For.24Document5 pagesThe Clinical Outcomes and Predictive Factors For.24KeziaNo ratings yet

- CasAre There Risk Factors For Splenic Rupture During Colonoscopy CaseDocument6 pagesCasAre There Risk Factors For Splenic Rupture During Colonoscopy Caseysh_girlNo ratings yet

- Etiology, Treatment Outcome and Prognostic Factors Among Patients With Secondary Peritonitis at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, TanzaniaDocument13 pagesEtiology, Treatment Outcome and Prognostic Factors Among Patients With Secondary Peritonitis at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzaniayossy aciNo ratings yet

- Complications of Pancreatic SurgeryDocument5 pagesComplications of Pancreatic Surgeryhenok seifeNo ratings yet

- Acute Colonic Pseudo-ObstructionDocument4 pagesAcute Colonic Pseudo-ObstructionJosé Luis Navarro Romero100% (1)

- Pill in Pocket NEJMDocument8 pagesPill in Pocket NEJMn2coolohNo ratings yet

- Marketing FinalDocument15 pagesMarketing FinalveronicaNo ratings yet

- Benevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualDocument123 pagesBenevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualSulay Avila LlanosNo ratings yet

- (500eboard) Version Coding Model 140 As of MY 1995Document1 page(500eboard) Version Coding Model 140 As of MY 1995Saimir SaliajNo ratings yet

- Appendix - Pcmc2Document8 pagesAppendix - Pcmc2Siva PNo ratings yet

- An Exploration of The Ethno-Medicinal Practices Among Traditional Healers in Southwest Cebu, PhilippinesDocument7 pagesAn Exploration of The Ethno-Medicinal Practices Among Traditional Healers in Southwest Cebu, PhilippinesleecubongNo ratings yet

- FMC Derive Price Action GuideDocument50 pagesFMC Derive Price Action GuideTafara MichaelNo ratings yet

- Vendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Document6 pagesVendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Chelsea EsparagozaNo ratings yet

- Plaza 66 Tower 2 Structural Design ChallengesDocument13 pagesPlaza 66 Tower 2 Structural Design ChallengessrvshNo ratings yet

- Soft Ground Improvement Using Electro-Osmosis.Document6 pagesSoft Ground Improvement Using Electro-Osmosis.Vincent Ling M SNo ratings yet

- Carriage RequirementsDocument63 pagesCarriage RequirementsFred GrosfilerNo ratings yet

- Psychological Contract Rousseau PDFDocument9 pagesPsychological Contract Rousseau PDFSandy KhanNo ratings yet

- Pt3 English Module 2018Document63 pagesPt3 English Module 2018Annie Abdul Rahman50% (4)

- ISO 9001 2015 AwarenessDocument23 pagesISO 9001 2015 AwarenessSeni Oke0% (1)

- User S Manual AURORA 1.2K - 2.2KDocument288 pagesUser S Manual AURORA 1.2K - 2.2KEprom ServisNo ratings yet

- School of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1Document2 pagesSchool of Mathematics 2021 Semester 1 MAT1841 Continuous Mathematics For Computer Science Assignment 1STEM Education Vung TauNo ratings yet

- Lecturenotes Data MiningDocument23 pagesLecturenotes Data Miningtanyah LloydNo ratings yet

- Objective & Scope of ProjectDocument8 pagesObjective & Scope of ProjectPraveen SehgalNo ratings yet

- DQ Vibro SifterDocument13 pagesDQ Vibro SifterDhaval Chapla67% (3)

- 3 Carbohydrates' StructureDocument33 pages3 Carbohydrates' StructureDilan TeodoroNo ratings yet

- DarcDocument9 pagesDarcJunior BermudezNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Machinery PDFDocument18 pagesDynamics of Machinery PDFThomas VictorNo ratings yet

- Turning PointsDocument2 pagesTurning Pointsapi-223780825No ratings yet

- Manual s10 PDFDocument402 pagesManual s10 PDFLibros18No ratings yet

- Leigh Shawntel J. Nitro Bsmt-1A Biostatistics Quiz No. 3Document6 pagesLeigh Shawntel J. Nitro Bsmt-1A Biostatistics Quiz No. 3Lue SolesNo ratings yet

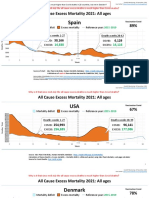

- Countries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021Document21 pagesCountries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021robaksNo ratings yet

- Report On GDP of Top 6 Countries.: Submitted To: Prof. Sunil MadanDocument5 pagesReport On GDP of Top 6 Countries.: Submitted To: Prof. Sunil MadanAbdullah JamalNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Pub - Bobs Refunding Ebook v3 PDFDocument65 pagesDokumen - Pub - Bobs Refunding Ebook v3 PDFJohn the First100% (3)

- Dalasa Jibat MijenaDocument24 pagesDalasa Jibat MijenaBelex ManNo ratings yet

- Application Activity Based Costing (Abc) System As An Alternative For Improving Accuracy of Production CostDocument19 pagesApplication Activity Based Costing (Abc) System As An Alternative For Improving Accuracy of Production CostM Agus SudrajatNo ratings yet

- Hole CapacityDocument2 pagesHole CapacityAbdul Hameed OmarNo ratings yet