Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hairy Woodpecker Feed Downy Woodpecker Nestlings in Florida

Uploaded by

BillPrantyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hairy Woodpecker Feed Downy Woodpecker Nestlings in Florida

Uploaded by

BillPrantyCopyright:

Available Formats

Florida Field Naturalist 38(2):71-72,2010.

HAIRY WOODPECKERS (Picoides uillosus) FEED DOWNY WOODPECKER

(I?pubescens) NESTLINGS

BILLPRANTY

Avian Ecology Lab, Archbold Biological Station, 123 Main Drive, Venus, Florida 33960

Current address: 8515 Village Mill Row, Bayonet Point, Florida 34667-2662

E-mail: billprantyOhotmail.com

Many instances of interspecific feeding in birds have been reported, and several explanations have been proposed (e.g., Shy 1982). A proximate cause that has received little emphasis is human disturbance. In this note, I relate a series of interspecific feeding

incidents with Hairy (Picoides uillosus) and Downy ( P pubescens) woodpeckers, and

suggest Lhat human disturbance caused the behavior.

On 21 March 1992, Mike Bessert discovered a pair of Hairy Woodpeckers excavating a

cavity about 8 m above the ground in a slash pine (Pinus elliottii var. densa) snag in

scrubby flatwoods habitat a t Archbold Biological Station, Highlands County, Florida. As

part of a demographic study, both adult woodpeckers had been color-banded in previous

years and were readily identifiable from their color bands. On 8 May 1992, I color-banded

their three nestlings, two females wiLh black crowns and one male with a red-orange

crown patch. While I was a t the nest, both adults returned with food, but could not feed

the nestlings due to my presence. Both adults eventually flew to a Downy Woodpecker

nest that was about 30 m away. The cavity of the Downy nest was approximately the same

height as the Hairy nest, was also in a slash pine snag, and was visible from the Hairy

nest. The Downy Woodpecker nest contained a t least two nestlings close to fledging (i.e., a

nestling head protruded from the cavity entrance when being fed) and the nestlings

begged loudly and nearly continuously. First Lhe male Hairy Woodpecker and then the female fed a t least one of the Downy Woodpecker nestlings before departing the area.

I monitored the Hairy Woodpecker nest before and a f k r the nestlings were banded

from a vantage point that allowed an unobslructed view of both woodpecker nests. On 5

May 1992, during a brief visiL to determine the agc of the nestlings, I watched as the female flew Lo the nest wiLh a billful of insects. She fed the young while she was perched

oulside the cavity, indicating that the nestlings would soon fledge (Jackson 1976). On 7

May, I watched the nest for 131 min, from 0744 Lo 0955 DST. During this time, the female fed the Hairy young eighL times (at 0746,0810,0823,0841,0918,0929,0936, and

0950),and the male Ted them three times (at 0750,0841, and 0932).

No nest watch was conducted on 8 May prior to banding, but I briefly checked the

nest 45 min after the young were returned to it. At that time, the nestling male was

looking out from Lhe cavity, and was soon fed by the breeding male.

On 9 May, I watched the nest for 132 min, from 0915 to 1127. The breeding male fed

the nestling male four times (at 0924, 0929, 0949, and 1021). The Temale flew into the

area with food seven times (at 0915,1015,1059, 1106, 1114, 1119, and 1125). On four of

Lhese occasions, she Ted Lhe Downy Woodpecker nestlings, and attempted to feed them

during two other visits but was repelled by the female Downy Woodpecker. During her final visit while I was watching the nest, the female Hairy Woodpecker flew to the Downy

Woodpecker nest tree, but I chased her away to try to induce her to resume feeding her

own young. AFter 1 min, Lhe Temale flew to her nest and fed the nestling male.

On 10 May, I watched the Hairy Woodpecker nest for 171 min, from 0832 to 1123.

The breeding male fed the neslling male Lhree times (at 0910, 0922, and 0932). The

72

FLORIDA FIELD NATURALIST

breeding female visited the area lhree times (at 0843,0941, and 1056).At 0843, she flew

to the Downy Woodpecker nest, but I chased her away. The female then spotted another

Hairy Woodpecker, which she repelled from the area. She fed no young during this visit.

The female returned a t 0941, and remained until 1016. She flew to lhe Downy Woodpecker nest seven times. I chased her away a t 0941, 1010, and 1014, and the female

Downy Woodpecker repelled her a t 0949,0951,0954, and 0957. Again, she fed no young.

At 1056, the female returned with food. She flew to the Downy Woodpecker nest, but I

chased her away. After 10 min, she flew back to the nest, but was repelled by the female

Downy Woodpecker. At 1116, while the nestling male Hairy Woodpecker was calling

loudly from the entrance of its nest cavity, the female Hairy Woodpecker fed the Downy

Woodpecker young, then departed.

On 11 May, I examined the two woodpecker nests from the ground and both appeared

to be empty. At 1122, I found lhe breeding male Hairy Woodpecker and the recently

fledged malc about 50 m south of the nest tree. On 21 May, both female Hairy Woodpecker

fledglings accompanied a parent about 1 krn south of the nest (R. Mumme pers. comm.).

The final observation of a young Hairy Woodpecker from this nest was on 5 June, when I

observed the fledgling male with the breeding female about 1.5 km south of the nest.

Shy (1982) summarized 140 cases of interspecific feeding among birds, and listed

their probable causes. She grouped the causes into eight categories: mixed clutches;

original nest or brood destroyed; close nesting by two species; young birds calling a s a

stimulus; orphaned young; male feeding another species while his mate was incubating;

unmated birds; and miscellaneous. The miscellaneous category contained the largest

number of entries, 41 (not 40 a s in Shy 1982:Table 2).

My observations of a pair of Hairy Woodpeckers feeding Downy Woodpecker nestlings fall into two of Shy's (1982) categories: (1) close nesting by two species; and (2)

young birds calling a s a stimulus. However, I feel i t was human disturbance that caused

the Hairy Woodpecker parents to feed the Downy Woodpecker nestlings. Shy (1982) does

not mention human disturbance a s a probable cause of interspecific feeding. Among

hundreds of references on the effects of human disturbance on birds, few references relate to interspecific feeding. Allen (1930 in Williams 1942), wrote of a brood ofAmerican

Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla) that had been removed from their nest and placed in the

hands of Allen's children to be photographed. The male redstart continued to feed the

young, but the female, "restrained by fear," instead fed nestling American Robins in a

nearby nest. An alternative explanation for the Hairy Woodpecker adults feeding the

Downy Woodpecker nestlings could be displacement behavior or redirected behavior due

to disturbance a t the nest (J.Jackson in litt.).

I thank Mike Bessert, Reed Bowman, Ron Mumme, and Keith Tarvin for field assistance, and Reed Bowman, Glen Woolfenden, and Jerry Jackson for improving drafts of

the manuscript. I thank John W. Fitzpatrick and Archbold Biological Station for supporting this research.

JACKSON,J. A. 1976. How to determine the status of a woodpecker nest. Living Bird

15:205-221.

SHY, M. M. 1982. Interspecific feeding among birds: A review. Journal of Field Ornithology 53:370-393.

WILLWVS, L. 1942. Interrelations in a nesting group of four species of birds. Wilson Bulletin 54:238-249.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Disappearance of The Budgerigar From The ABA AreaDocument7 pagesThe Disappearance of The Budgerigar From The ABA AreaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Neotropic Cormorant Records in FloridaDocument6 pagesNeotropic Cormorant Records in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Red-Legged Thrush Habitat at Maritime Hammock SanctuaryDocument4 pagesRed-Legged Thrush Habitat at Maritime Hammock SanctuaryBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Purple Swamphen Persistence in FloridaDocument12 pagesPurple Swamphen Persistence in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Important Bird Areas of Florida, Draft 3Document220 pagesImportant Bird Areas of Florida, Draft 3BillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Bronzed Cowbird First Breeding Record in FloridaDocument7 pagesBronzed Cowbird First Breeding Record in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 112th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaDocument3 pages112th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Wakulla Seaside Sparrow Biological Status ReportDocument16 pagesWakulla Seaside Sparrow Biological Status ReportBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- ABA Checklist Committee Report 2008-2009Document6 pagesABA Checklist Committee Report 2008-2009BillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- 110th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaDocument3 pages110th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- 111th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaDocument3 pages111th Christmas Bird Count Summary For FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Purple Swamphen Natural History in FloridaDocument8 pagesPurple Swamphen Natural History in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Non-Established Exotic Birds in The ABA AreaDocument13 pagesNon-Established Exotic Birds in The ABA AreaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- ABA Checklist Committee Report 2009-2010Document10 pagesABA Checklist Committee Report 2009-2010BillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Worthington's Marsh Wren Biological Status ReportDocument14 pagesWorthington's Marsh Wren Biological Status ReportBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- New Winter Records in Florida For Common Nighthawk, Cliff Swallow, Red-Eyed Vireo, and Bobolink, and First Recent Winter Record of Mississippi KiteDocument6 pagesNew Winter Records in Florida For Common Nighthawk, Cliff Swallow, Red-Eyed Vireo, and Bobolink, and First Recent Winter Record of Mississippi KiteBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Townsend's Solitaire First Recotf For FloridaDocument6 pagesTownsend's Solitaire First Recotf For FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- European Turtle-Dove Record Reassessment in FloridaDocument8 pagesEuropean Turtle-Dove Record Reassessment in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- ABA Checklist Committee Report, 2011Document8 pagesABA Checklist Committee Report, 2011BillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Scott's Seaside Sparrow Biological Stayus Review in FloridaDocument15 pagesScott's Seaside Sparrow Biological Stayus Review in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Shorebirds and Larids at Lake Okeechobee, FloridaDocument12 pagesShorebirds and Larids at Lake Okeechobee, FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Swainson's Thrush Winter Record in FloridaDocument3 pagesSwainson's Thrush Winter Record in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Painted Bunting Breeding Abundance and Habitat Use in FloridaDocument12 pagesPainted Bunting Breeding Abundance and Habitat Use in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Tribute To Paul HessDocument13 pagesTribute To Paul HessBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Common Myna Status and Distribution in FloridaDocument8 pagesCommon Myna Status and Distribution in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Nanday Parakeet Nests in FloridaDocument11 pagesNanday Parakeet Nests in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Red-Whiskered Bulbul Range in FloridaDocument4 pagesRed-Whiskered Bulbul Range in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- Marian's Marsh Wren Biological Status Review in FloridaDocument14 pagesMarian's Marsh Wren Biological Status Review in FloridaBillPrantyNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Apc 8x Install Config Guide - rn0 - LT - enDocument162 pagesApc 8x Install Config Guide - rn0 - LT - enOney Enrique Mendez MercadoNo ratings yet

- Medpet Pigeon ProductsDocument54 pagesMedpet Pigeon ProductsJay Casem67% (3)

- Practice of Epidemiology Performance of Floating Absolute RisksDocument4 pagesPractice of Epidemiology Performance of Floating Absolute RisksShreyaswi M KarthikNo ratings yet

- CERADocument10 pagesCERAKeren Margarette AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Ethamem-G1: Turn-Key Distillery Plant Enhancement With High Efficiency and Low Opex Ethamem TechonologyDocument25 pagesEthamem-G1: Turn-Key Distillery Plant Enhancement With High Efficiency and Low Opex Ethamem TechonologyNikhilNo ratings yet

- Social Studies SbaDocument12 pagesSocial Studies SbaSupreme KingNo ratings yet

- SPA For Banks From Unit OwnersDocument1 pageSPA For Banks From Unit OwnersAda DiansuyNo ratings yet

- 9 To 5 Props PresetsDocument4 pages9 To 5 Props Presetsapi-300450266100% (1)

- Comm Part For A320Document1 pageComm Part For A320ODOSNo ratings yet

- Acc101Q7CE 5 3pp187 188 1Document3 pagesAcc101Q7CE 5 3pp187 188 1Haries Vi Traboc MicolobNo ratings yet

- Tumors of The Central Nervous System - VOL 12Document412 pagesTumors of The Central Nervous System - VOL 12vitoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Report No 2Document11 pagesClinical Case Report No 2ملک محمد صابرشہزاد50% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Cfm56-3 Engine Regulation by CFMDocument43 pagesCfm56-3 Engine Regulation by CFMnono92100% (5)

- HierbasDocument25 pagesHierbasrincón de la iohNo ratings yet

- Philippines implements external quality assessment for clinical labsDocument2 pagesPhilippines implements external quality assessment for clinical labsKimberly PeranteNo ratings yet

- Parasitology Lecture Hosts, Symbiosis & TransmissionDocument10 pagesParasitology Lecture Hosts, Symbiosis & TransmissionPatricia Ann JoseNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 7 Tabata TrainingDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 7 Tabata Trainingapi-392909015100% (1)

- FinalsDocument8 pagesFinalsDumpNo ratings yet

- Test Report OD63mm PN12.5 PE100Document6 pagesTest Report OD63mm PN12.5 PE100Im ChinithNo ratings yet

- Cot 1 Vital SignsDocument22 pagesCot 1 Vital Signscristine g. magatNo ratings yet

- Immune System Quiz ResultsDocument6 pagesImmune System Quiz ResultsShafeeq ZamanNo ratings yet

- Urban Drainage Modelling Guide IUD - 1Document196 pagesUrban Drainage Modelling Guide IUD - 1Helmer Edgardo Monroy GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Endocrown Review 1Document9 pagesEndocrown Review 1Anjali SatsangiNo ratings yet

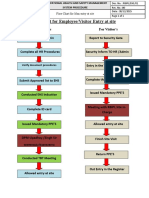

- fLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYDocument2 pagesfLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYshamshad ahamedNo ratings yet

- Elem. Reading PracticeDocument10 pagesElem. Reading PracticeElissa Janquil RussellNo ratings yet

- Case Studies On Industrial Accidents - 2Document84 pagesCase Studies On Industrial Accidents - 2Parth N Bhatt100% (2)

- Subaru Forester ManualsDocument636 pagesSubaru Forester ManualsMarko JakobovicNo ratings yet

- Insurance Principles, Types and Industry in IndiaDocument10 pagesInsurance Principles, Types and Industry in IndiaAroop PalNo ratings yet

- Sigma monitor relayDocument32 pagesSigma monitor relayEdwin Oria EspinozaNo ratings yet

- DR - Hawary Revision TableDocument3 pagesDR - Hawary Revision TableAseel ALshareefNo ratings yet

- Mastering Parrot Behavior: A Step-by-Step Guide to Building a Strong Relationship with Your Avian FriendFrom EverandMastering Parrot Behavior: A Step-by-Step Guide to Building a Strong Relationship with Your Avian FriendRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (69)

- Crazy for the Storm: A Memoir of SurvivalFrom EverandCrazy for the Storm: A Memoir of SurvivalRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (217)

- The Last of His Kind: The Life and Adventures of Bradford Washburn, America's Boldest MountaineerFrom EverandThe Last of His Kind: The Life and Adventures of Bradford Washburn, America's Boldest MountaineerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Dark Summit: The True Story of Everest's Most Controversial SeasonFrom EverandDark Summit: The True Story of Everest's Most Controversial SeasonRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (154)

- The Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsFrom EverandThe Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsNo ratings yet