Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bartok String Quartets (Complete) .Unlocked

Uploaded by

Mr. PadzyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bartok String Quartets (Complete) .Unlocked

Uploaded by

Mr. PadzyCopyright:

Available Formats

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

Page 8

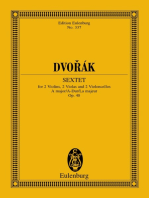

BARTK

String Quartets

Also available:

(Complete)

Vermeer Quartet

8.555998

8.557433

2 CDs

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

Page 2

Bla Bartk (1881-1945)

The Six String Quartets

The string quartets of Bla Bartk occupy a central

position in the classical repertoire of the twentieth

century. Not only are they a milestone in the evolution

of the quartet literature, but, along with those by Haydn

and Beethoven, they provide an overview of their

composers output at all the main junctures of his

career. This might be thought surprising when one

remembers that Bartk was a pianist by training and,

latterly, by profession, though the store he set by the

medium is confirmed by the way in which each of the

quartets exemplifies those facets of his music which

preoccupied him prior to, and during the course of its

composition. It is this, coupled with the intrinsic quality

of each work, that gives the cycle its inclusiveness and

significance in the context of Western music as a whole.

Although he had written several quartets in his

adolescence, Bartk was 27 before he embarked on his

first acknowledged work in the medium. While the

pieces that precede it, notably the Rhapsody for Piano

and Orchestra (1904), the Second Orchestral Suite

(1907), the Bagatelles for piano (1908) and the First

Violin Concerto (1908), evince a gradually evolving

persona, only with the First Quartet (1909) did he

achieve a convincing amalgam of main influences,

notably Strauss and Debussy, such as allows his own

voice to come through. Moreover, for all that it recalls

these composers in its harmonic intricacy and

expressive license, the impact of folk-song, which

Bartk had been collecting for barely two years, is

already apparent in the rhythmic drive and cumulative

momentum that informs this music.

The three movements proceed without pause, such

that the second is in constant acceleration, in contrast to

the uniform tempo of the first, and with the generally

fast finale itself prefaced by a slow introduction. The

sighing motif which begins the Lento will permeate all

aspects of the piece: whether the expressive polyphony

to which it gives rise, or (beginning with reiterated cello

chords) the more melodic dialogue which forms the

8.557543-44

central section. The Allegretto that follows is in constant

search of a stable tempo, keeping its material in a state

of flux, though with a repeated-note motif as an

important formal marker. Its uncertainty is decisively

countered by an Introduzione which, by means of

unison gestures and solo recitatives, leads to the Allegro

vivace, dominated by a folk-like theme initiated by the

cello. A more expansive passage divides off the two

main sections of this finale, which culminates in a

pungent reprise of the main theme and a powerful coda

uniting all of the salient ideas in affirmative accord.

The years that followed were among the most

difficult of Bartks career. With the opera Duke

Bluebeards Castle (1911) having been rejected by the

Budapest Opera as unperformable, and the stylistically

ambivalent ballet The Wooden Prince (1916) remaining

unorchestrated for several years, he largely withdrew

from active involvement in musical life to concentrate

on his folk-song researches. The length of time that he

worked on the Second Quartet (1915-17) is partly

explained by this enforced period of isolation, partly by

the overriding need to fashion a musical language in

which the art and folk music aspects of his creativity

were allowed to find their natural equilibrium. The

synthesis has been all but made in the present quartet,

which ranks among his most inward and personal

achievements.

There are again three movements, this time

following the slow-fast-slow format which frequently

found favour in the twentieth century. The opening

Moderato grows from a searching theme on viola,

which, after a modally-inflected idea has provided

contrast, propels the impassioned central climax. A

varied and intensified recall of the main material leads

into the pensively ambivalent close. If this movement

marks the limit of Bartks late-romantic leanings, the

scherzo that follows clearly points the way forward. The

motoric rhythms of its main theme and the yearning trio

section breathe the spirit of peasant culture, while the

Also available:

8.554718

8.555329

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

CD 1

Page 6

75:49

String Quartet No. 1, Op. 7 (1908-1909)

1 I Lento attacca

2 II Poco a poco accelerando Allegretto

3 III Introduzione Allegro attacca: Allegro vivace

29:24

9:08

8:26

11:50

String Quartet No. 3 (1927)

4 Prima parte: Moderato attacca:

5 Seconda parte: Allegro attacca:

6 Ricapitulazione della prima parte: Moderato Coda: Allegro molto

15:17

4:54

5:37

4:45

String Quartet No. 5 (1934)

7 I Allegro

8 II Adagio molto

9 III Scherzo

0 IV Andante

! V Finale: Allegro vivace

31:09

7:28

6:01

5:18

5:08

7:13

CD 2

78:34

String Quartet No. 2, Op. 17 (1915-1917)

1 I Moderato

2 II Allegro molto capriccioso

3 III Lento

26:19

9:58

7:37

8:43

String Quartet No. 4 (1928)

4 I Allegro

5 II Prestissimo, con sordino

6 III Non troppo lento

7 IV Allegretto pizzicato

8 V Allegro molto

23:08

6:15

3:08

5:12

2:49

5:45

String Quartet No. 6 (1939)

9 I Mesto Pi mosso, pesante Vivace

0 II Mesto Marcia

! III Mesto Burletta

@ IV Mesto

29:06

7:38

7:44

7:12

6:32

8.557543-44

scurrying coda anticipates the angular musical

expression to come. The finale returns to the inwardness

of hitherto, its terse initial motif spawning a freelyevolving theme which together define the harmonic and

melodic content of the Lento as a whole. The closing

bars are not so much defeatist as fatalistic - as though

the composers solitude had afforded him a measure of

self-recognition.

The intensity of this piece was maintained in those

that followed, above all, the brutal pantomime The

Miraculous Mandarin (1919) and the two Violin

Sonatas (1921 and 1922), in which Bartks music

approaches a peak of chromatic intensity. Then, in the

unlikely guise of a Dance Suite (1923) written to

commemorate the founding of the modern Hungarian

capital, he broke through to a harmonically more clearcut manner that was to have profound consequences for

the works to come. Three years of relative silence were

broken by music written for himself to play, namely the

First Piano Concerto, the Piano Sonata, and the Out of

Doors suite (all 1926). Then, in the Third Quartet

(1927), Bartk achieved an integration of folk idioms

with a Beethovenian contrapuntal resource such he as

not to surpass.

Although it unfolds as a seamless whole, the quartet

comprises two main parts which themselves divide into

four sections, the work thus following a sonata-form

layout in principle as well as in spirit. The Prima parte

presents the principal ideas, respectively ruminative and

malevolent, in the manner of an exposition, before an

acerbic climax and a modally-inflected codetta. The

Seconda parte is launched with a pizzicato idea, which

provides the motivation for a tumultuous development

of the material heard thus far: many of the playing

techniques synonymous with Bartks later quartet

writing are here used extensively for the first time. At its

apex, the music spills over into the Recapitulazione

della prima parte, a transformed and generally

restrained reprise of the main ideas, with which the

work seems to be heading for a muted close. The Coda

steals in, however, to draw the motivic threads into a

taut continuum, laying bare the musics harmonic and

tonal premises with breathtaking conclusiveness.

While the Fourth Quartet (1928) was to follow

barely a year later, its formal precepts could hardly have

been more different from the preceding work. Although

he had made use of a five-movement arch structure as

far back as the First Orchestral Suite (1905), it was only

in this piece that Bartk fully utilized its potential for

maximum expressive variety within a balanced and

symmetrical framework.

As in rhythm and harmony, so in tonal orientation

does the piece move, as in a palindrome, to the centre

and outwards again; though this will not be readily

perceived in the opening Allegro, whose vigorous

contrapuntal discourse partly conceals a regular sonataform movement, with contrasting main themes, an

intensifying central development and an extended coda.

The first scherzo, played virtually con sordino

throughout, has a restless, spectral air which

complements its ceaseless momentum. The slow

movement is the epicentre: emerging out of a brooding

cello melody, heard against a static harmonic backdrop,

it reaches a peak of fervency before returning to its

pensive origins. The second scherzo, played pizzicato

throughout, is more overtly characterful than its

predecessor, an emotional opening-out which is

pursued in the finale. This transforms the first

movements expressive territory with appreciably

greater zest, before bringing the work to a headlong and

exhilarating close.

The formal poise thus attained was to be put to

productive use in such subsequent works as the Cantata

Profana (1930) and the Second Piano Concerto (1931).

The pressures of performing and academic

commitments left Bartk little time for composition in

the three years that followed, and though the Fifth

Quartet (1934) might be thought to continue the

essential thinking of its predecessor, its formal aims and

expressive content make it an altogether different

proposition. At its centre is a scherzo, this time enclosed

by two slow movements, while the unwavering

emphasis on counterpoint that marks out the previous

quartet is here tempered by a harmonic lucidity and an

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

underlying tonal direction, qualities such as combine to

make it perhaps the most approachable quartet of

Bartks maturity.

This greater directness is immediately evident in the

opening Allegro, its formal divisions audible at first

hearing, and in which reiterated chords endow the music

with a more direct tonal trajectory. The contrast between

the vigorous and expressive main themes is itself more

pronounced, with the latters overt lyricism continued in

the first slow movement. This is an Adagio whose

ethereal beginning evolves into a dialogue of rapt

tenderness, only briefly ruffled by the agitated middle

section. Marked Alla bulgarese, the scherzo has a

distinctive gait as well as a robust humour and, in its

trio, a quixotic alternation of textures. The Andante

draws on its slow predecessor in a variation of earlier

ideas, given focus by the rhythmic devices of walking

motion and rapid-fire chords. A long-range developing

of material that is intensified in the finale, whose charge

through its sonata-form ground-plan is halted by the

distorted allusion to a popular song, one which offsets

the conclusiveness of the works ending to unsettling

effect.

Although it saw the emergence of such masterpieces

as the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936),

the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937) and the

Second Violin Concerto (1938), the second half of the

1930s was to be a time of intense soul-searching for

Bartk. Increasingly alienated by the deterioration of the

European political landscape in general, and by the

increasingly fascistic stance of the Hungarian government

in particular, he first banned all performances of his

music in his native country, before opting for selfimposed exile in the United States. Understandable, then,

that a combined sense of dread and resignation in the face

of the inevitable, should permeate all aspects of the Sixth

Quartet (1939), composed in the months prior to the

outbreak of World War Two.

8.557543-44

01:42pm

Page 4

For all that it adopts the traditional four movements

and continues the drive towards a greater tonal and

harmonic lucidity of his final decade, the quartet is

among Bartks most equivocal statements. The first

three movements are prefaced by a Mesto theme, which

achieves fuller scoring and greater pathos at each return.

First, a solo viola presentation leads to a sonata

movement whose onward progress is questioned and

sidestepped at every formal juncture. Next, a cello

rendering with tremolo accompaniment leads to a march

whose rhythmic profile is the only stable element in a

movement of bitter irony and, in the central section,

wrenching emotional intensity. Then, a three-part

version leads to a burlesque which pointedly conflates

the popular and the grotesque, with the only solace

coming in a brief trio. Finally, a full quartet presentation

makes the Mesto theme into the subject of the entire last

movement, one which pursues an avowedly melancholic

path before a conclusion of poised uncertainty.

Even though he was, at length, able, in such works

as the Concerto for Orchestra (1943), the Solo Violin

Sonata (1944) and the Third Piano Concerto (1945), to

surmount the difficulties posed by financial hardship

and failing health, Bartk was not to return to the

medium of the string quartet. At his death a Viola

Concerto was left in semi-drafted form, while the

opening bars of a Seventh Quartet bear tantalizing

witness to the composers continuing commitment to,

and belief in the medium. What might have resulted is

impossible to guess. Better to focus attention instead on

what is left to us, a cycle of quartets whose consistency

of form and content is strikingly akin to the sets of six

that Haydn frequently composed, and a range and depth

of expression such as truly embodies a lifetime of

experience.

Vermeer Quartet

Shmuel Ashkenasi, Violin Mathias Tacke, Violin Richard Young, Viola Marc Johnson, Cello

With performances in practically every major city and every prestigious music festival in North and South America,

Europe, the Far East, and Australia, the Vermeer Quartet has achieved international stature as one of the worlds

finest classical music ensembles. Formed in 1969 at Marlboro, the Vermeer makes its permanent home in Chicago,

while serving as resident artists at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb since 1970, and as Fellows at the Royal

Northern College of Music in Manchester in England, where the quartet has given annual master classes since 1978.

Since 1984 the quartet has been the resident quartet for Performing Arts Chicago. Recordings include the complete

string quartets of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Bartk, with various other works by Schubert, Brahms,

Shostakovich, Mendelssohn, Schnittke, Verdi, Haydn, Tchaikovsky, and Dvok. The violinist Shmuel Ashkenasi

was born in Israel, where he was a student of Ilona Feher. He later studied with Efrem Zimbalist at the Curtis

Institute in Philadelphia. He was the winner of the Merriweather Post Competition, a finalist in the Queen Elisabeth

Competition, and second prize-winner in the Tchaikovsky Competition. He has performed with many of the worlds

leading orchestras in the United States, Europe, the Soviet Union, and Japan, and has appeared in recital with

Murray Perahia and Peter Serkin. The violinist Mathias Tacke is originally from Bremen. He studied with Ernst

Mayer-Schierning in Detmold, with Emanuel Hurwitz and David Takeno in London, and with Sandor Vegh in

Cornwall. He won first prize in the Jugend Musiziert National Competition, and graduated with honours from the

Nordwestdeutsche Musikakademie, where he was later appointed to the faculty. From 1983 to 1992 he was a

member of the Ensemble Modern, one of the most important professional groups specialising in twentieth century

music. Richard Young, who plays viola in the quartet, studied with Josef Gingold, Aaron Rosand, William

Primrose, and Zoltn Szkely. At the age of thirteen he was invited to perform for Queen Elizabeth of Belgium.

Since then he has appeared as a soloist with various orchestras and has given recitals throughout the United States.

A special award winner in the Rockefeller Foundation American Music Competition, he was a member of both the

New Hungarian Quartet and the Rogeri Trio. He has taught at the University of Michigan and the Peoples Music

School in Chicago, and was chairman of the String Department of Oberlin Conservatory. The cellist Marc Johnson

studied in Lincoln, Nebraska, with Carol Work, at the Eastman School of Music with Ronald Leonard, and at

Indiana University with Janos Starker and Josef Gingold. While still a student, he was the youngest member of the

Rochester Philharmonic, and has subsequently performed as a soloist with that orchestra. In addition to numerous

other awards, he won first prize in the prestigious Washington International Competition. Before joining the

Vermeer Quartet he was a member of the Pittsburgh Symphony.

Richard Whitehouse

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

underlying tonal direction, qualities such as combine to

make it perhaps the most approachable quartet of

Bartks maturity.

This greater directness is immediately evident in the

opening Allegro, its formal divisions audible at first

hearing, and in which reiterated chords endow the music

with a more direct tonal trajectory. The contrast between

the vigorous and expressive main themes is itself more

pronounced, with the latters overt lyricism continued in

the first slow movement. This is an Adagio whose

ethereal beginning evolves into a dialogue of rapt

tenderness, only briefly ruffled by the agitated middle

section. Marked Alla bulgarese, the scherzo has a

distinctive gait as well as a robust humour and, in its

trio, a quixotic alternation of textures. The Andante

draws on its slow predecessor in a variation of earlier

ideas, given focus by the rhythmic devices of walking

motion and rapid-fire chords. A long-range developing

of material that is intensified in the finale, whose charge

through its sonata-form ground-plan is halted by the

distorted allusion to a popular song, one which offsets

the conclusiveness of the works ending to unsettling

effect.

Although it saw the emergence of such masterpieces

as the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936),

the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937) and the

Second Violin Concerto (1938), the second half of the

1930s was to be a time of intense soul-searching for

Bartk. Increasingly alienated by the deterioration of the

European political landscape in general, and by the

increasingly fascistic stance of the Hungarian government

in particular, he first banned all performances of his

music in his native country, before opting for selfimposed exile in the United States. Understandable, then,

that a combined sense of dread and resignation in the face

of the inevitable, should permeate all aspects of the Sixth

Quartet (1939), composed in the months prior to the

outbreak of World War Two.

8.557543-44

01:42pm

Page 4

For all that it adopts the traditional four movements

and continues the drive towards a greater tonal and

harmonic lucidity of his final decade, the quartet is

among Bartks most equivocal statements. The first

three movements are prefaced by a Mesto theme, which

achieves fuller scoring and greater pathos at each return.

First, a solo viola presentation leads to a sonata

movement whose onward progress is questioned and

sidestepped at every formal juncture. Next, a cello

rendering with tremolo accompaniment leads to a march

whose rhythmic profile is the only stable element in a

movement of bitter irony and, in the central section,

wrenching emotional intensity. Then, a three-part

version leads to a burlesque which pointedly conflates

the popular and the grotesque, with the only solace

coming in a brief trio. Finally, a full quartet presentation

makes the Mesto theme into the subject of the entire last

movement, one which pursues an avowedly melancholic

path before a conclusion of poised uncertainty.

Even though he was, at length, able, in such works

as the Concerto for Orchestra (1943), the Solo Violin

Sonata (1944) and the Third Piano Concerto (1945), to

surmount the difficulties posed by financial hardship

and failing health, Bartk was not to return to the

medium of the string quartet. At his death a Viola

Concerto was left in semi-drafted form, while the

opening bars of a Seventh Quartet bear tantalizing

witness to the composers continuing commitment to,

and belief in the medium. What might have resulted is

impossible to guess. Better to focus attention instead on

what is left to us, a cycle of quartets whose consistency

of form and content is strikingly akin to the sets of six

that Haydn frequently composed, and a range and depth

of expression such as truly embodies a lifetime of

experience.

Vermeer Quartet

Shmuel Ashkenasi, Violin Mathias Tacke, Violin Richard Young, Viola Marc Johnson, Cello

With performances in practically every major city and every prestigious music festival in North and South America,

Europe, the Far East, and Australia, the Vermeer Quartet has achieved international stature as one of the worlds

finest classical music ensembles. Formed in 1969 at Marlboro, the Vermeer makes its permanent home in Chicago,

while serving as resident artists at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb since 1970, and as Fellows at the Royal

Northern College of Music in Manchester in England, where the quartet has given annual master classes since 1978.

Since 1984 the quartet has been the resident quartet for Performing Arts Chicago. Recordings include the complete

string quartets of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Bartk, with various other works by Schubert, Brahms,

Shostakovich, Mendelssohn, Schnittke, Verdi, Haydn, Tchaikovsky, and Dvok. The violinist Shmuel Ashkenasi

was born in Israel, where he was a student of Ilona Feher. He later studied with Efrem Zimbalist at the Curtis

Institute in Philadelphia. He was the winner of the Merriweather Post Competition, a finalist in the Queen Elisabeth

Competition, and second prize-winner in the Tchaikovsky Competition. He has performed with many of the worlds

leading orchestras in the United States, Europe, the Soviet Union, and Japan, and has appeared in recital with

Murray Perahia and Peter Serkin. The violinist Mathias Tacke is originally from Bremen. He studied with Ernst

Mayer-Schierning in Detmold, with Emanuel Hurwitz and David Takeno in London, and with Sandor Vegh in

Cornwall. He won first prize in the Jugend Musiziert National Competition, and graduated with honours from the

Nordwestdeutsche Musikakademie, where he was later appointed to the faculty. From 1983 to 1992 he was a

member of the Ensemble Modern, one of the most important professional groups specialising in twentieth century

music. Richard Young, who plays viola in the quartet, studied with Josef Gingold, Aaron Rosand, William

Primrose, and Zoltn Szkely. At the age of thirteen he was invited to perform for Queen Elizabeth of Belgium.

Since then he has appeared as a soloist with various orchestras and has given recitals throughout the United States.

A special award winner in the Rockefeller Foundation American Music Competition, he was a member of both the

New Hungarian Quartet and the Rogeri Trio. He has taught at the University of Michigan and the Peoples Music

School in Chicago, and was chairman of the String Department of Oberlin Conservatory. The cellist Marc Johnson

studied in Lincoln, Nebraska, with Carol Work, at the Eastman School of Music with Ronald Leonard, and at

Indiana University with Janos Starker and Josef Gingold. While still a student, he was the youngest member of the

Rochester Philharmonic, and has subsequently performed as a soloist with that orchestra. In addition to numerous

other awards, he won first prize in the prestigious Washington International Competition. Before joining the

Vermeer Quartet he was a member of the Pittsburgh Symphony.

Richard Whitehouse

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

CD 1

Page 6

75:49

String Quartet No. 1, Op. 7 (1908-1909)

1 I Lento attacca

2 II Poco a poco accelerando Allegretto

3 III Introduzione Allegro attacca: Allegro vivace

29:24

9:08

8:26

11:50

String Quartet No. 3 (1927)

4 Prima parte: Moderato attacca:

5 Seconda parte: Allegro attacca:

6 Ricapitulazione della prima parte: Moderato Coda: Allegro molto

15:17

4:54

5:37

4:45

String Quartet No. 5 (1934)

7 I Allegro

8 II Adagio molto

9 III Scherzo

0 IV Andante

! V Finale: Allegro vivace

31:09

7:28

6:01

5:18

5:08

7:13

CD 2

78:34

String Quartet No. 2, Op. 17 (1915-1917)

1 I Moderato

2 II Allegro molto capriccioso

3 III Lento

26:19

9:58

7:37

8:43

String Quartet No. 4 (1928)

4 I Allegro

5 II Prestissimo, con sordino

6 III Non troppo lento

7 IV Allegretto pizzicato

8 V Allegro molto

23:08

6:15

3:08

5:12

2:49

5:45

String Quartet No. 6 (1939)

9 I Mesto Pi mosso, pesante Vivace

0 II Mesto Marcia

! III Mesto Burletta

@ IV Mesto

29:06

7:38

7:44

7:12

6:32

8.557543-44

scurrying coda anticipates the angular musical

expression to come. The finale returns to the inwardness

of hitherto, its terse initial motif spawning a freelyevolving theme which together define the harmonic and

melodic content of the Lento as a whole. The closing

bars are not so much defeatist as fatalistic - as though

the composers solitude had afforded him a measure of

self-recognition.

The intensity of this piece was maintained in those

that followed, above all, the brutal pantomime The

Miraculous Mandarin (1919) and the two Violin

Sonatas (1921 and 1922), in which Bartks music

approaches a peak of chromatic intensity. Then, in the

unlikely guise of a Dance Suite (1923) written to

commemorate the founding of the modern Hungarian

capital, he broke through to a harmonically more clearcut manner that was to have profound consequences for

the works to come. Three years of relative silence were

broken by music written for himself to play, namely the

First Piano Concerto, the Piano Sonata, and the Out of

Doors suite (all 1926). Then, in the Third Quartet

(1927), Bartk achieved an integration of folk idioms

with a Beethovenian contrapuntal resource such he as

not to surpass.

Although it unfolds as a seamless whole, the quartet

comprises two main parts which themselves divide into

four sections, the work thus following a sonata-form

layout in principle as well as in spirit. The Prima parte

presents the principal ideas, respectively ruminative and

malevolent, in the manner of an exposition, before an

acerbic climax and a modally-inflected codetta. The

Seconda parte is launched with a pizzicato idea, which

provides the motivation for a tumultuous development

of the material heard thus far: many of the playing

techniques synonymous with Bartks later quartet

writing are here used extensively for the first time. At its

apex, the music spills over into the Recapitulazione

della prima parte, a transformed and generally

restrained reprise of the main ideas, with which the

work seems to be heading for a muted close. The Coda

steals in, however, to draw the motivic threads into a

taut continuum, laying bare the musics harmonic and

tonal premises with breathtaking conclusiveness.

While the Fourth Quartet (1928) was to follow

barely a year later, its formal precepts could hardly have

been more different from the preceding work. Although

he had made use of a five-movement arch structure as

far back as the First Orchestral Suite (1905), it was only

in this piece that Bartk fully utilized its potential for

maximum expressive variety within a balanced and

symmetrical framework.

As in rhythm and harmony, so in tonal orientation

does the piece move, as in a palindrome, to the centre

and outwards again; though this will not be readily

perceived in the opening Allegro, whose vigorous

contrapuntal discourse partly conceals a regular sonataform movement, with contrasting main themes, an

intensifying central development and an extended coda.

The first scherzo, played virtually con sordino

throughout, has a restless, spectral air which

complements its ceaseless momentum. The slow

movement is the epicentre: emerging out of a brooding

cello melody, heard against a static harmonic backdrop,

it reaches a peak of fervency before returning to its

pensive origins. The second scherzo, played pizzicato

throughout, is more overtly characterful than its

predecessor, an emotional opening-out which is

pursued in the finale. This transforms the first

movements expressive territory with appreciably

greater zest, before bringing the work to a headlong and

exhilarating close.

The formal poise thus attained was to be put to

productive use in such subsequent works as the Cantata

Profana (1930) and the Second Piano Concerto (1931).

The pressures of performing and academic

commitments left Bartk little time for composition in

the three years that followed, and though the Fifth

Quartet (1934) might be thought to continue the

essential thinking of its predecessor, its formal aims and

expressive content make it an altogether different

proposition. At its centre is a scherzo, this time enclosed

by two slow movements, while the unwavering

emphasis on counterpoint that marks out the previous

quartet is here tempered by a harmonic lucidity and an

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

Page 2

Bla Bartk (1881-1945)

The Six String Quartets

The string quartets of Bla Bartk occupy a central

position in the classical repertoire of the twentieth

century. Not only are they a milestone in the evolution

of the quartet literature, but, along with those by Haydn

and Beethoven, they provide an overview of their

composers output at all the main junctures of his

career. This might be thought surprising when one

remembers that Bartk was a pianist by training and,

latterly, by profession, though the store he set by the

medium is confirmed by the way in which each of the

quartets exemplifies those facets of his music which

preoccupied him prior to, and during the course of its

composition. It is this, coupled with the intrinsic quality

of each work, that gives the cycle its inclusiveness and

significance in the context of Western music as a whole.

Although he had written several quartets in his

adolescence, Bartk was 27 before he embarked on his

first acknowledged work in the medium. While the

pieces that precede it, notably the Rhapsody for Piano

and Orchestra (1904), the Second Orchestral Suite

(1907), the Bagatelles for piano (1908) and the First

Violin Concerto (1908), evince a gradually evolving

persona, only with the First Quartet (1909) did he

achieve a convincing amalgam of main influences,

notably Strauss and Debussy, such as allows his own

voice to come through. Moreover, for all that it recalls

these composers in its harmonic intricacy and

expressive license, the impact of folk-song, which

Bartk had been collecting for barely two years, is

already apparent in the rhythmic drive and cumulative

momentum that informs this music.

The three movements proceed without pause, such

that the second is in constant acceleration, in contrast to

the uniform tempo of the first, and with the generally

fast finale itself prefaced by a slow introduction. The

sighing motif which begins the Lento will permeate all

aspects of the piece: whether the expressive polyphony

to which it gives rise, or (beginning with reiterated cello

chords) the more melodic dialogue which forms the

8.557543-44

central section. The Allegretto that follows is in constant

search of a stable tempo, keeping its material in a state

of flux, though with a repeated-note motif as an

important formal marker. Its uncertainty is decisively

countered by an Introduzione which, by means of

unison gestures and solo recitatives, leads to the Allegro

vivace, dominated by a folk-like theme initiated by the

cello. A more expansive passage divides off the two

main sections of this finale, which culminates in a

pungent reprise of the main theme and a powerful coda

uniting all of the salient ideas in affirmative accord.

The years that followed were among the most

difficult of Bartks career. With the opera Duke

Bluebeards Castle (1911) having been rejected by the

Budapest Opera as unperformable, and the stylistically

ambivalent ballet The Wooden Prince (1916) remaining

unorchestrated for several years, he largely withdrew

from active involvement in musical life to concentrate

on his folk-song researches. The length of time that he

worked on the Second Quartet (1915-17) is partly

explained by this enforced period of isolation, partly by

the overriding need to fashion a musical language in

which the art and folk music aspects of his creativity

were allowed to find their natural equilibrium. The

synthesis has been all but made in the present quartet,

which ranks among his most inward and personal

achievements.

There are again three movements, this time

following the slow-fast-slow format which frequently

found favour in the twentieth century. The opening

Moderato grows from a searching theme on viola,

which, after a modally-inflected idea has provided

contrast, propels the impassioned central climax. A

varied and intensified recall of the main material leads

into the pensively ambivalent close. If this movement

marks the limit of Bartks late-romantic leanings, the

scherzo that follows clearly points the way forward. The

motoric rhythms of its main theme and the yearning trio

section breathe the spirit of peasant culture, while the

Also available:

8.554718

8.555329

8.557543-44

557543-44 bk Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

Page 8

BARTK

String Quartets

Also available:

(Complete)

Vermeer Quartet

8.555998

8.557433

2 CDs

8.557543-44

557543-44 rr Bartok US

20/07/2005

01:42pm

Page 1

CMYK

NAXOS

NAXOS

DDD

Playing Time

Bla

2:34:23

BARTK

(1881-1945)

The Complete String Quartets

CD 2

78:34

1-3 String Quartet No. 2, Op. 17 (1915-1917)

26:19

23:08

29:06

4-8 String Quartet No. 4 (1928)

9-@ String Quartet No. 6 (1939)

Vermeer Quartet

Shmuel Ashkenasi, Violin 1 Mathias Tacke, Violin 2

Richard Young, Viola Marc Johnson, Cello

8.557543-44

8.557543-44

Recorded at St John Chrysostom Church, Newmarket, Ontario, Canada,

from May 24th to 27th, 2001, February 10th to 12th, 2003, and February 8th to 11th, 2004

Producers: Norbert Kraft and Bonnie Silver Engineer: Norbert Kraft Editor: Bonnie Silver

Publishers: Universal Edition Booklet Notes: Richard Whitehouse

Cover Picture: Summer, 1917-18 by Lyubov Sergeevna Popova (1889-1924)

(Museum of Art, Tula, Russia / www.bridgeman.co.uk)

h g

7-! String Quartet No. 5 (1934)

29:24

15:17

31:09

4-6 String Quartet No. 3 (1927)

& 2005

Naxos Rights International Ltd.

75:49

1-3 String Quartet No. 1, Op. 7 (1908-1909)

Booklet notes in English

Made in Canada

CD 1

BARTK: String Quartets (Complete)

8.557543-44

www.naxos.com

BARTK: String Quartets (Complete)

The string quartets of Bla Bartk occupy a central position in the classical repertoire of the twentieth

century. Not only are they a milestone in the evolution of the quartet literature, but along with those

by Haydn and Beethoven they provide an overview of their composers output at all the main

junctures of his career. The First Quartet is a convincing amalgam of influences, notably Strauss and

Debussy, the Second Quartet more introspective, while the Third and Fourth Quartets contain the most

difficult music of the six. The Fifth is the most approachable, while the Sixth is permeated by a sense

of dread and resignation at the approach of World War Two. These masterpieces truly offer the range

and depth of a lifetimes creative experience.

You might also like

- Schnittke - String Quartet No. 3 - Program NotesDocument12 pagesSchnittke - String Quartet No. 3 - Program NotesvladvaideanNo ratings yet

- MJuloxPT Movie String Quartets For Festivals Weddings and 5 BookDocument4 pagesMJuloxPT Movie String Quartets For Festivals Weddings and 5 BookmjoudeNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Britten String QuartetDocument12 pagesBenjamin Britten String QuartetstrawberryssNo ratings yet

- Kokkonen Cello Sonata - Piano and CelloDocument39 pagesKokkonen Cello Sonata - Piano and CelloJob PolvorizaNo ratings yet

- ScordaturaDocument74 pagesScordaturaPiano MontrealNo ratings yet

- APPLYING THE ŠEVČIK ANALYTICAL STUDIES METHOD TO BARTÓK'S CONCERTO FOR VIOLA AND ORCHESTRA: A PERFORMER'S GUIDE by MEGAN CHISOM PEYTONDocument103 pagesAPPLYING THE ŠEVČIK ANALYTICAL STUDIES METHOD TO BARTÓK'S CONCERTO FOR VIOLA AND ORCHESTRA: A PERFORMER'S GUIDE by MEGAN CHISOM PEYTONRodrigo Balthar FurmanNo ratings yet

- Concerto For Violin and OrchestraDocument98 pagesConcerto For Violin and OrchestraBya BiancaNo ratings yet

- Ligeti Second String Quartet Analysis Final PDFDocument31 pagesLigeti Second String Quartet Analysis Final PDFRodrigo BjnNo ratings yet

- Debussys String Quartet in G Minor, Op. 10, and The Influence of Cesar Franck, and Who It Influenced.Document5 pagesDebussys String Quartet in G Minor, Op. 10, and The Influence of Cesar Franck, and Who It Influenced.Emily Louise Taylor100% (1)

- String QuartetDocument26 pagesString QuartetjotarelaNo ratings yet

- String Orchestra CatalogueDocument44 pagesString Orchestra CatalogueNemanja1978100% (4)

- Artamonova Borisovsky 1 PDFDocument9 pagesArtamonova Borisovsky 1 PDFEmil HasalaNo ratings yet

- Benjamin - String Quartet No 2Document47 pagesBenjamin - String Quartet No 2Tomislav OliverNo ratings yet

- Arvo Pärt, Summa, String Orchestra Version - YouTubeDocument25 pagesArvo Pärt, Summa, String Orchestra Version - YouTubecadorna10% (5)

- Mendelssohn Piano Trio op. 49 Performance Style AnalysisDocument3 pagesMendelssohn Piano Trio op. 49 Performance Style AnalysisAudrey100% (1)

- Berg Violin Concerto ArticleDocument7 pagesBerg Violin Concerto ArticleSamNo ratings yet

- Hindemith 1939 Viola Sonata PaperDocument23 pagesHindemith 1939 Viola Sonata PaperGreg LuceNo ratings yet

- Pavan for Three CellosDocument1 pagePavan for Three CellosAna DomingasNo ratings yet

- Kronos QuartetDocument2 pagesKronos Quartetmoromarino3663No ratings yet

- Faure Piano Quartet - C MinorDocument8 pagesFaure Piano Quartet - C MinorMatthew David SamsonNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Black Angels For String Quartet of George CrumbDocument25 pagesAnalysis of Black Angels For String Quartet of George CrumbJoshua100% (1)

- Violin ConcertoDocument92 pagesViolin ConcertoWen ZichenNo ratings yet

- Henryk Wieniawski: Eight Violin EtudesDocument22 pagesHenryk Wieniawski: Eight Violin Etudesnicolasteodoriu100% (2)

- Ligeti Second String Quartet Analysis Final PDFDocument31 pagesLigeti Second String Quartet Analysis Final PDFΑσπασία ΦράγκουNo ratings yet

- Cello Concerti by Lutosławski and DutilleuxDocument25 pagesCello Concerti by Lutosławski and DutilleuxBol Dig100% (2)

- Cello ConcertosDocument12 pagesCello ConcertosPintér NóraNo ratings yet

- Elements of Style in Lutoslawski's Symphony No.4, by Payman Akhlaghi (2004), Graduate Paper in Composition and Musicology, (2004, UCLA)Document13 pagesElements of Style in Lutoslawski's Symphony No.4, by Payman Akhlaghi (2004), Graduate Paper in Composition and Musicology, (2004, UCLA)Payman Akhlaghi (پیمان اخلاقی)100% (2)

- Richard Strauss Metamorphosen PartiturDocument94 pagesRichard Strauss Metamorphosen PartiturObi Wan KalafoNo ratings yet

- 2021 VCE Music Prescribed List of Notated Solo Works: VioloncelloDocument7 pages2021 VCE Music Prescribed List of Notated Solo Works: VioloncelloAnonymous 3q8gr2HmNo ratings yet

- Geiringer Schubert Arpeggione Sonata 1979Document11 pagesGeiringer Schubert Arpeggione Sonata 1979ipromesisposi0% (1)

- Shostakovich String Quartets, Selected Poetic ResponsesDocument2 pagesShostakovich String Quartets, Selected Poetic Responsesalwaysbusylosing0% (1)

- Interpretation of Bach Sonata No. 1 - Adagio and Fugue PDFDocument19 pagesInterpretation of Bach Sonata No. 1 - Adagio and Fugue PDFlidya evaniaNo ratings yet

- Brahms - Piano Quintet in F Minor Op. 34Document68 pagesBrahms - Piano Quintet in F Minor Op. 34Matt GoochNo ratings yet

- Partes de OrquestaDocument11 pagesPartes de OrquestaDavid ChapaNo ratings yet

- Schuman Violin Concerto AnalysisDocument29 pagesSchuman Violin Concerto AnalysisJNo ratings yet

- String Quartet No.4 AnalysisDocument65 pagesString Quartet No.4 AnalysisSam Ostroff100% (1)

- The Piano Oeuvre of Leos Janacek. Transcendence Through Programmatism (Abstract)Document33 pagesThe Piano Oeuvre of Leos Janacek. Transcendence Through Programmatism (Abstract)AndyNo ratings yet

- Pression For Cello Lachenman AnalysisDocument20 pagesPression For Cello Lachenman Analysiskrakus5813100% (1)

- William Kinderman - The String Quartets of Beethoven-University of Illinois Press (2006) PDFDocument360 pagesWilliam Kinderman - The String Quartets of Beethoven-University of Illinois Press (2006) PDFNicolas Labriola100% (2)

- Alban BergDocument13 pagesAlban BergMelissa CultraroNo ratings yet

- Chamber Music in Historic Sites 2010-11 Season BrochureDocument17 pagesChamber Music in Historic Sites 2010-11 Season BrochureDaCameraSocietyNo ratings yet

- Clara Schumann - Trio Op. 17, AnalizaDocument10 pagesClara Schumann - Trio Op. 17, Analizamaumau100% (1)

- Ernest Bloch's Musical Influences and Style in Oregon As Demonstrated Through His Unaccompanied Cello Suite #1Document25 pagesErnest Bloch's Musical Influences and Style in Oregon As Demonstrated Through His Unaccompanied Cello Suite #1Evan Pardi100% (1)

- Text, Movement and Music: An Annotated Catalogue of (Selected) Percussion Works 1950 - 2006Document57 pagesText, Movement and Music: An Annotated Catalogue of (Selected) Percussion Works 1950 - 2006MatiasOliveraNo ratings yet

- Bilkent University Analysis of Bartok's Viola ConcertoDocument31 pagesBilkent University Analysis of Bartok's Viola Concertowasita adi100% (1)

- Prokofiev Classical SymphonyDocument57 pagesProkofiev Classical SymphonyAndrás HusztiNo ratings yet

- String QuartetDocument2 pagesString QuartetChad GardinerNo ratings yet

- CassadoDocument58 pagesCassadoYotam Levy100% (5)

- Aaron Copland's Piano Sonata and Violin SonataDocument3 pagesAaron Copland's Piano Sonata and Violin SonataFabio CastielloNo ratings yet

- Possible Etudes Spiccato - CelloDocument1 pagePossible Etudes Spiccato - CelloFernando GarNo ratings yet

- Cello Sonata - WebernDocument22 pagesCello Sonata - WebernAlejandro AcostaNo ratings yet

- César Franck - A New French UnityDocument150 pagesCésar Franck - A New French UnityPepe Capricornio100% (1)

- A Russian Rhetoric of Form in The Music of W. Lutoslawski PDFDocument28 pagesA Russian Rhetoric of Form in The Music of W. Lutoslawski PDFEzioNo ratings yet

- The Search For Consistent Intonation - An Exploration and Guide FoDocument136 pagesThe Search For Consistent Intonation - An Exploration and Guide FoJose Manuel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Gesture Overview PDFDocument89 pagesGesture Overview PDFJoan Bagés RubíNo ratings yet

- Analysis BartokDocument109 pagesAnalysis BartokBrad Bergeron100% (5)

- IMSLP02344-Debussy - String Quartet No.1Document52 pagesIMSLP02344-Debussy - String Quartet No.1MaestroJovich100% (1)

- Playboy Calender 2014Document14 pagesPlayboy Calender 2014Mr. Padzy40% (5)

- Max43TutorialsAndTopics PDFDocument354 pagesMax43TutorialsAndTopics PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Songtrust Ebook PDFDocument38 pagesSongtrust Ebook PDFMr. Padzy100% (2)

- Hummel EScoDocument121 pagesHummel EScoKarla RamirezNo ratings yet

- Recnik Eu TerminologijeDocument49 pagesRecnik Eu Terminologijeistojilovic100% (1)

- Isaiah Berlin Tchaikovsky and Pushkin PDFDocument7 pagesIsaiah Berlin Tchaikovsky and Pushkin PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Cedeum Knjiga o PozoristuDocument228 pagesCedeum Knjiga o PozoristuSnezana Savic CokaNo ratings yet

- Europe On The Move, The Story of The EU, Chart PDFDocument1 pageEurope On The Move, The Story of The EU, Chart PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Dimensions For CD CoversDocument2 pagesDimensions For CD CoversMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Chopin and Scriabin Etudes PDFDocument79 pagesChopin and Scriabin Etudes PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Analasys of Schumann's Fantasie Op. 17Document133 pagesAnalasys of Schumann's Fantasie Op. 17Mr. Padzy100% (4)

- Top 10 Greatest Italian Film DirectorsDocument10 pagesTop 10 Greatest Italian Film DirectorsMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Carpathian ConventionDocument15 pagesCarpathian ConventionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- The State of European Cities in Transition 2010Document29 pagesThe State of European Cities in Transition 2010Mr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Recnik Eu TerminologijeDocument49 pagesRecnik Eu Terminologijeistojilovic100% (1)

- MOZART Horn Duos Horn QuintetDocument3 pagesMOZART Horn Duos Horn QuintetMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- The Urban Settlement Network in Serbia - Initial DataDocument4 pagesThe Urban Settlement Network in Serbia - Initial DataMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- MUSIC Its Laws and EvolutionDocument354 pagesMUSIC Its Laws and EvolutionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Speech at a Gypsy FuneralDocument1 pageSpeech at a Gypsy FuneralMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Carpathian ConventionDocument15 pagesCarpathian ConventionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Britten Let's Make An Opera! Little Sweep Study GuideDocument14 pagesBenjamin Britten Let's Make An Opera! Little Sweep Study GuideMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Lettering in Fifteenth Century Florentine PaintingDocument28 pagesLettering in Fifteenth Century Florentine PaintingMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Carpathian ConventionDocument15 pagesCarpathian ConventionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Commedia Vs OperaSeriaDocument4 pagesCommedia Vs OperaSeriaMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Web Revcache Review - 11663 PDFDocument3 pagesWeb Revcache Review - 11663 PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Carpathian ConventionDocument15 pagesCarpathian ConventionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Exit Timeline Web PDFDocument1 pageExit Timeline Web PDFMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Carpathian ConventionDocument15 pagesCarpathian ConventionMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Speech at a Gypsy FuneralDocument1 pageSpeech at a Gypsy FuneralMr. PadzyNo ratings yet

- Music Theory: DiscoveringDocument5 pagesMusic Theory: DiscoveringAby MosNo ratings yet

- Class Piano SyllabusDocument4 pagesClass Piano SyllabusJeana JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Sonata For Violin Solo No. 3 in D Minor "Ballade" - YouTubeDocument3 pagesSonata For Violin Solo No. 3 in D Minor "Ballade" - YouTuberodNo ratings yet

- Dido Purcell-To The Hills and The ValesDocument8 pagesDido Purcell-To The Hills and The ValesAnthony KevinNo ratings yet

- Blockis Recorder FingeringsDocument3 pagesBlockis Recorder FingeringsTin2xNo ratings yet

- From Sound To SymbolDocument23 pagesFrom Sound To Symbolapi-308383811No ratings yet

- Adam Koss - Comparison of Grpahs of Chromatic and Diatonic ScaleDocument7 pagesAdam Koss - Comparison of Grpahs of Chromatic and Diatonic Scalemumsthewordfa100% (1)

- 8 - Alto Sax 1 PDFDocument32 pages8 - Alto Sax 1 PDFPedro Filipe RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Improvising Jazz On The Violin Pt. 2: Learning PatternsDocument2 pagesImprovising Jazz On The Violin Pt. 2: Learning PatternsHarry ScorzoNo ratings yet

- Peterson StroboPlus Owner's ManualDocument18 pagesPeterson StroboPlus Owner's ManualAxe YardNo ratings yet

- CochraneDocument46 pagesCochraneCynthia RiveraNo ratings yet

- Ben Lunn - Article About Radulescu "The Quest", Op. 90Document6 pagesBen Lunn - Article About Radulescu "The Quest", Op. 90Nikolya Ulyanov100% (1)

- ITunes Acoustic Fingerstyle GuitarDocument47 pagesITunes Acoustic Fingerstyle Guitardavide201050% (4)

- quartal jazz piano voicings pdf free downloadDocument2 pagesquartal jazz piano voicings pdf free downloadMariano Trangol Gallardo0% (2)

- Joshi Music Editing Assignment - REVISEDDocument1 pageJoshi Music Editing Assignment - REVISEDrohanfreakNo ratings yet

- Schutz PaperDocument8 pagesSchutz PaperJack BreslinNo ratings yet

- Beginner Bass Guitar BreakdownDocument4 pagesBeginner Bass Guitar BreakdownSamson Linus0% (2)

- Guitar Chords Na Jaane Kyu (Strings)Document2 pagesGuitar Chords Na Jaane Kyu (Strings)Nurul Hussain KhanNo ratings yet

- Allen Forte Ocatónicas PDFDocument75 pagesAllen Forte Ocatónicas PDFMarta FloresNo ratings yet

- Top 15 Bollywood Guitar SongsDocument21 pagesTop 15 Bollywood Guitar SongsAincognitozNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Ich Grolle Nicht by Robert SchumannDocument2 pagesAnalysis On Ich Grolle Nicht by Robert SchumannKevin Choi100% (3)

- Stomp! - Brothers Johnson (Download Bass Transcription and Bass Tab in Best Quality at WWW - Nicebasslines.com)Document5 pagesStomp! - Brothers Johnson (Download Bass Transcription and Bass Tab in Best Quality at WWW - Nicebasslines.com)nicebasslines_com91% (11)

- The Overtures of RossiniDocument30 pagesThe Overtures of RossiniOlga SofiaNo ratings yet

- Wes Montgomery''s - SnowfallDocument1 pageWes Montgomery''s - SnowfallBalthazzarNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 6 - 4TH Quarter Summative Test 1-4Document4 pagesMapeh 6 - 4TH Quarter Summative Test 1-4Maureen VillacobaNo ratings yet

- Musica Dolorsa: Double Bass For String OrchestraDocument5 pagesMusica Dolorsa: Double Bass For String OrchestraMarco BadamiNo ratings yet

- Nina - GminDocument3 pagesNina - GminColinNo ratings yet

- Liquid Lunch - Electric BassDocument3 pagesLiquid Lunch - Electric BassOliver DPNo ratings yet

- Pablo Sarasate - Zigeunerweisen Trumpet in BDocument2 pagesPablo Sarasate - Zigeunerweisen Trumpet in Bbluedragons199260100% (4)

- Agawu1989 PDFDocument28 pagesAgawu1989 PDFhariskohNo ratings yet