Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Romanticism Nature This Lime Tree Bower My Prison

Uploaded by

amyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Romanticism Nature This Lime Tree Bower My Prison

Uploaded by

amyCopyright:

Available Formats

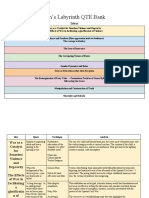

Amy L.

Kleinvachter

Dr. Kimberly DeFazio

3 March 2015

English 204: English Literature II

Mid-Term Paper

The Relationship between Nature and Spirituality in Romantic Literature

The 19th century, often called the romantic era, was a time of unfathomable change and

transformation. The west went from an agricultural to an industrial society, science emerged and

we saw the spark of industrial revolutions, and the idea of nationalism came forth bringing with

it a demand for authority. The 19th century also became a defining moment for the way in which

literature would be composed and thought of. It was within the romantic era that we saw the birth

of many great writers and literary works, and it was their ideas and philosophical trains of

thought that were most impressive and noteworthy. The writers of this time, oppressed by the

power of authority and the revolutions, were in search of freedom in their personal and political

lives. As they began searching for this freedom, they let their ever creative imaginations take on

far greater tasks than ever before, and outpoured their feelings, emotions, and senses into their

literature. Hand in hand, with their great respect for imagination and emotions, romantic writers

found nature to be one of their most peaceful and powerful assets. Nature to them was tranquil,

powerful, divine, and an escape from the harsh economic and political realities of the world at

this time. The romantics had a very special relationship with nature, and it is that relationship

that raises many questions. One of the biggest questions I have is, how powerful of a religious

role did romantic writers place on nature? Was nature more powerful than God himself?

Thinking on that, the rest of this paper will go on to analytically explore the powerful, romantic

ideals of nature and religion. I will specifically focus on the romantic writer, Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, who had emerged at this time. I will show how he gave nature a religious power. I

believe he thought so highly of nature that he saw nature as more powerful than God. As we

analyze his writings we will see this argument slowly unfold (Damrosch and Dettmar 7-26).

Studying Coleridges writings, there is undoubtedly one theme in common, and that is the

idea of nature. Coleridge saw nature as sublime. He gave it a sense of divinity, and used it in a

way to connect with the human soul. As we talk about nature and its divinity I want to bring to

our attention a poem called, This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison, written by Coleridge. For some

background information, the poem starts out with the speaker, Coleridge, explaining how he

suffered an injury to his foot and is unable to go on a walk through nature with his visiting

friends. Unable to participate, he compares a garden of lime trees he is sitting in to a prison cell,

because finds himself discouraged and sadden by the fact that he is missing out. So he puts

himself in their shoes, and begins to wildly imagine what he thinks they are seeing. As his

imagination takes him on this imaginative walk, he realizes his power to connect with nature,

which we will see becomes a key aspect of this poem (Damrosch and Dettmar 561).

The first part of the poem I want to discuss begins with Coleridge describing his friends

walking through a dark, damp ravine, arriving at a waterfall, and then emerging under a wide

heaven overlooking a beautiful landscape. Looking at the lines specifically Coleridge states:

Fannd by the water-fall! And there my friends

Behold the dark green file of long lank Weeds,

That all at once (a most magnificent sight!)[]

Now, my Friends emerge

Beneath the wide wide Heaven and view again

The many-steepled track magnificent

Of hilly fields and meadows, and the sea (16-24).

It is important to note that before these lines, Coleridge describes nature as having a very dark

and eerie presence. He then imagines his friends traveling through a ravine, which I believe

Coleridge used to symbolize as a very low point in someones life. For example, the ravine could

have symbolized the many struggles people faced in the romantic era both politically and

personally. It could have also symbolized his emotions at the time he was writing this poem,

because he was devastated about not being able to go on the walk. Continuing on in the poem,

Coleridge then imagines his friends arriving at the waterfall which he describes as a most

magnificent sight, as the lines say above. When he describes the waterfall as a most significant

sight, I related the water of the waterfall to a baptismal scene, because as the water spread its

moisture on the nature around it, Coleridge imagined his friends emerging under the wide heaven

looking at a breathtaking landscape. From this I got a sense that, Coleridge or his friends, were in

tough times which was symbolized by the ravine, came upon the waterfall and were cleansed by

God, and then ultimately guided to a better place as they emerged under the wide heaven. In

broader terms, when Coleridge says his friends emerge beneath the wide heaven he is comparing

the sky to a heaven like symbol. This gives the sky a very God-like, inviting and limitless aspect.

It is also important to note that these lines come right after he imagines his friends walking

through the ravine, a symbol of struggle and tragedy in life. So, this shows that after you seek

nature the power is limitless, and nature has a God-like presence in everyones life whether they

see it or not. I feel as though Coleridge compared a walk through nature to being the same as a

walk through a life where God is always present. Coleridge showed us that even in the darkest of

times, if you appreciate nature, God will give you strength and lead you to a better place.

Continuing on, the next few lines only add to this God-like image of nature. When Coleridge

says many steepled-tracks, I believe he compares the hills in the landscape where his friends

emerge to steeples of a church. So, I believe Coleridge saw nature as a place of worship. The

word many is also important because it describes nature as having many churches or places of

worship. This lead me to think Coleridge saw nature as a far greater being than man, because it

had many places of worship unlike in the city where they had just a church. In other words,

Coleridge viewed nature as having more religious power than man.

At this point, we need to introduce Charles, one of Coleridges dear friends. As Coleridge

describes it, Charles was a working man who lived in the industrialized city, which put a burden

on him because he was unable to experience and connect with nature. Along with living in the

city, we also need to note that Charles had recently experienced a very tragic event when his

sister, who at the time was mentally unstable, killed their mother. This left Charles feeling very

depressed, and in search for something to heal his heartache (Damrosch and Dettmar 561-2).

Now that we know who Charles is, we can analyze one of more powerful passages of

Coleridges poem. The passage reads:

So my Friend

Struck with deep joy may stand, as I have stood,

Silent with swimming sense; yea, gazing round

On the wide landscape, gaze till all doth seem

Less gross than bodily; and such hues

As cloath the Almighty Spirit, when yet he makes

Spirits perceive his presence. (37-43)

In these lines, Coleridge is referring to Charles when he says my friend, and he explains how

he hopes Charles can find joy and peace in one of natures most beautiful creations, the sunset, as

he himself has done before. The sunset being so beautiful is a sign that it is very powerful. In this

case, Coleridge had asked nature to paint such a beautiful scene because he thought Charles

needed an escape from not only the harsh realities of the hectic city scene, but also an emotional

uplifting from his recent family tragedy. The sunset is Coleridges hope that Charles can forget

about his sorrow for a minute and just embrace the beautiful scene that nature is painting in front

of him. He hopes Charles can spiritually connect with his soul when looking at the sunset, and

find the strength to push through these tough times. In a sense, the sunset was so beautiful and

empowering that Charles, overwhelmed by its beauty, experienced something very spiritual. It

was as if the sunset had more power than God, in the way Coleridge described the effects it had

on Charles.

As the poem continues, we see that Charless soul is renewed by appreciating nature and

its beauty. We also see Coleridge finds peace himself. The more he imagines the spiritual

connection Charles is having, the more he personally feels spiritually enlightened. He begins to

realize that even though he didnt go on the walk, he can still be satisfied and connect with

natures sublime power. He realizes that as long as he appreciates nature, no matter where he is,

it will always provide him with what he needs. He shows this realization when he states,

Henceforth I shall know/ That nature neer deserts the wise and pure (59-60). In other words,

nature is a powerful tool and spiritual being to those who appreciate it. By now, it is clear to take

away the message that nature is very God-like. It can be seen as a place of worship, and a place

to connect with your soul. Specifically for Coleridge, nature was a place of consolation. He

essentially saw nature as a force as powerful as God. To him, as long as you appreciated nature

and embraced it, it would always offer its healing power and strength. He emphasized the idea

that nature, with its beauty, could be more powerful to man than God himself.

After analyzing these few scenes from Coleridges This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison,

and showing how nature was more powerful than God, I want to bring in a second piece of

literature. I want to analyze how some of the ideas from chapter one in Nealon and Girouxs

book, The Theory Toolbox, relate to the thoughtful construction of Coleridges poem. Chapter

one discusses theory in a way that one might not think of it, and questions the conventional ways

of thinking. As Nealon and Giroux said, were interested in theory as approach, as a wider

toolbox for intervening in contemporary cultures (Nealon and Giroux 7). In other words, the

way in which we interpret or think about something is very critical. The more we can critically

analyze something, the more we can draw from it. If we can see past the normal consistencies of

facts and think outside the box, the better off we will be. This made me think of how Coleridge

conducted his thoughts and analyzed nature. For example, in Coleridges imaginative walk he

emphasized ideas and concepts about nature that not everyone was aware of. He could see things

in nature most others couldnt. The God-like power he portrayed in nature was taking a relatively

popular romantic ideal, and turning it into something much more. I also want to point out that

Nealon and Giroux said a few times, what we think changes how we act (Nealon and Giroux

5). This concept was also very much so present throughout the poem. We repeatedly saw how

Coleridges thoughts dictated how he felt. He was depressed in the beginning, and then after

imagining the walk and connecting with nature he felt spiritually enlightened. As soon as he was

able to think differently and shed light on other ideals his lime tree bower wasnt a prison

anymore. Rather, his surroundings were just as beautiful and spiritually connecting as his friends

walk. This proves that how we think, truly does alter how we act. If we can think of nature as this

powerful spiritual being, then we can soulfully connect with it. This was one of Coleridges most

powerful assets. The more he could see nature in a different light the more he got out of it, and in

the end we see him share that idea with his best friend Charles.

In conclusion, there is two main ideas we need to take away from this analysis. First, we

need to realize that Coleridge saw nature as more powerful than God. He appreciated nature to

such a high degree that it was a Godly figure for him. He could find spiritual consolation, and the

more he appreciated it the more powerful that connection became. Second, the way in which he

conducted his thoughts was very important. If he wasnt able to abstractly think about nature as

the God-like figure he saw it as, he would have never felt the way he did about it. So, it is critical

we analyze the way in which someone thinks about something, because those who cant see

outside the box of natural facts will never really see the true beauty in things.

Works Cited

Coleridge, Taylor S. This Lime Tree Prison My Bower. The Longman Anthology of British

Literature Vol. 2 4th ed. Eds. David Damrosch and Kevin J. Dettmar. Boston: Longman.

2010. 561-3.

Damrosch, David and Kevin Dettmar. The Romantics and Their Contemporaries. The

Longman Anthology of British Literature Vol. 2 4th ed. Eds. David Damrosch and Kevin

J. Dettmar. Boston: Longman. 2010. 3-33.

Nealon Jeffery and Susan Searls Giroux. The Theory Toolbox. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman &

Littlefield. 2012. 1-8.

You might also like

- Philip K. Dick - Humans And Androids: Literary essay by Eric BandiniFrom EverandPhilip K. Dick - Humans And Androids: Literary essay by Eric BandiniNo ratings yet

- The crucible: Hale pleads for Proctor's testimonyDocument3 pagesThe crucible: Hale pleads for Proctor's testimonyThảo huỳnhNo ratings yet

- Confessions Of An Inquirer: "Advice is like snow; the softer it falls, the longer it dwells upon, and the deeper it sinks into the mind."From EverandConfessions Of An Inquirer: "Advice is like snow; the softer it falls, the longer it dwells upon, and the deeper it sinks into the mind."No ratings yet

- Carlsonrichard III PaperDocument35 pagesCarlsonrichard III Paperapi-272615928No ratings yet

- Looking For Richard Script Commentary 1Document28 pagesLooking For Richard Script Commentary 1Vaibhav KhannaNo ratings yet

- Old Man with Wings AnalysisDocument3 pagesOld Man with Wings AnalysisMartinNo ratings yet

- Do Computers DreamDocument6 pagesDo Computers Dream2501motokoNo ratings yet

- Android NarrativeDocument1 pageAndroid NarrativeCaroline RhudeNo ratings yet

- The Odyssey Background Notes TextbookDocument3 pagesThe Odyssey Background Notes Textbookapi-332060185No ratings yet

- Neoclassicism II: Culture and Society in The Eighteenth CenturyDocument3 pagesNeoclassicism II: Culture and Society in The Eighteenth CenturySara PattersonNo ratings yet

- Module A - Exploring Connections (King Richard III/ Looking For Richard)Document2 pagesModule A - Exploring Connections (King Richard III/ Looking For Richard)Jay CherizNo ratings yet

- On Buying Flowers and Other (Not So) Ordinary EventsDocument59 pagesOn Buying Flowers and Other (Not So) Ordinary EventsthereisnousernameNo ratings yet

- 9 ASP LitchartDocument10 pages9 ASP Litchartvenkata.krishnanNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes of Sept 19Document6 pagesLecture Notes of Sept 19Greg LoncaricNo ratings yet

- Pans Labyrinth & DystopiaDocument22 pagesPans Labyrinth & DystopiaBea BrabanteNo ratings yet

- Readers Response NotesDocument9 pagesReaders Response Notesapi-235184247No ratings yet

- Pastoral, Satire, and Ecology in The Modern Memorial Park: Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One and Forest LawnDocument61 pagesPastoral, Satire, and Ecology in The Modern Memorial Park: Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One and Forest LawnbeepyouNo ratings yet

- Pan's Labyrinth Movie Review and AnalysisDocument3 pagesPan's Labyrinth Movie Review and AnalysisMSMNo ratings yet

- Summary Analysis On, "Tonal Cues and Uncertain Values: Affect and Ethics in Mrs. Dalloway"Document2 pagesSummary Analysis On, "Tonal Cues and Uncertain Values: Affect and Ethics in Mrs. Dalloway"Lee GullicksonNo ratings yet

- Brave New WorldDocument2 pagesBrave New Worldjrich9250% (2)

- Dystopian Literature Unit OverviewDocument2 pagesDystopian Literature Unit Overviewapi-290988513No ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution Textbook PagesDocument5 pagesIndustrial Revolution Textbook Pagesapi-306956814No ratings yet

- HSC Ext 1 Program and Assessment 2019Document1 pageHSC Ext 1 Program and Assessment 2019SIYU YANNo ratings yet

- The Stream of Consciousness Novel That Inspired The HoursDocument13 pagesThe Stream of Consciousness Novel That Inspired The HoursJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Reading - A Very Old Man With Enormous WingsDocument3 pagesReading - A Very Old Man With Enormous WingsDaniella SantosNo ratings yet

- Segal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Document27 pagesSegal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Claudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Themes in The Crucible WorksheetDocument2 pagesThemes in The Crucible Worksheetapi-241350182No ratings yet

- A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings - TextDocument6 pagesA Very Old Man With Enormous Wings - TextAlex yangNo ratings yet

- Richard III Notes For ExamDocument2 pagesRichard III Notes For ExamLouise AnsellNo ratings yet

- Parent Question StemsDocument6 pagesParent Question Stemsapi-261186529No ratings yet

- Essay Outline AssignmentDocument28 pagesEssay Outline AssignmentKhin Thazin MinNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's Richard III and Pacino's Looking for Richard highlight evolution of valuesDocument3 pagesShakespeare's Richard III and Pacino's Looking for Richard highlight evolution of valuesMehdiNo ratings yet

- 'A Kestrel For A Knave' Character RelationshipsDocument4 pages'A Kestrel For A Knave' Character RelationshipsNicholas Wezley BahadoorsinghNo ratings yet

- Eng Ext1 - Pans Labyrinth Quotes and AnalysisDocument22 pagesEng Ext1 - Pans Labyrinth Quotes and Analysiskat100% (1)

- How Does Miller Dramatically Convey in This Passage The Tensions and Hatred in Salem WilliamDocument2 pagesHow Does Miller Dramatically Convey in This Passage The Tensions and Hatred in Salem WilliamWilliam0% (2)

- Paradise Engineering ? A Reality or Nightmare ?Document40 pagesParadise Engineering ? A Reality or Nightmare ?Lisa ClancyNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Tradition in Homer's Odyssey - by Marcel BasDocument17 pagesThe Meaning of Tradition in Homer's Odyssey - by Marcel BasMarcel Bas100% (1)

- Tragedy in The Modern Age The Case of Arthur Miller PDFDocument6 pagesTragedy in The Modern Age The Case of Arthur Miller PDFChris F OrdlordNo ratings yet

- "The Hours" Insight: Students Balaban Olivia Banu Oana DR Ăjneanu AdelaDocument30 pages"The Hours" Insight: Students Balaban Olivia Banu Oana DR Ăjneanu AdelarossifcdNo ratings yet

- A Very Old Man With Enormous WingsDocument4 pagesA Very Old Man With Enormous WingsRimshaNo ratings yet

- Orwell's Animal Farm analysisDocument2 pagesOrwell's Animal Farm analysisStentel MicaelaNo ratings yet

- Richard III QuotesDocument4 pagesRichard III QuotesJason ChaserNo ratings yet

- Guide To Asking Questions in LiteratureDocument6 pagesGuide To Asking Questions in LiteratureReizel GarciaNo ratings yet

- Homer and The Will of ZeusDocument25 pagesHomer and The Will of Zeusvince34No ratings yet

- Avoiding RepetitionDocument5 pagesAvoiding RepetitionAlexander PalenciaNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Swift Gullivers TravelsDocument17 pagesJonathan Swift Gullivers TravelsMartaCampilloNo ratings yet

- The Hours CompatibilityDocument11 pagesThe Hours Compatibilityalz66No ratings yet

- Ancient World, The OdysseyDocument6 pagesAncient World, The OdysseyAnastasia CamoctrokovaNo ratings yet

- How Have The Contexts of The Composers of Richard The Third and Looking For Richard Affected Their Portrayal of Their Key Themes?Document3 pagesHow Have The Contexts of The Composers of Richard The Third and Looking For Richard Affected Their Portrayal of Their Key Themes?christinaNo ratings yet

- English Study NotesDocument32 pagesEnglish Study NotesKareem AghaNo ratings yet

- Magical Realism Enormous WingsDocument2 pagesMagical Realism Enormous WingsArooj BibiNo ratings yet

- Jane Austen-Main Features of Her WritingDocument7 pagesJane Austen-Main Features of Her WritingCecilia KennedyNo ratings yet

- A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings: A Tale For Children: Gabriel Garcia MarquezDocument4 pagesA Very Old Man With Enormous Wings: A Tale For Children: Gabriel Garcia MarquezJenniferHavensNo ratings yet

- Crucible Act4 From TextbookDocument16 pagesCrucible Act4 From TextbookEthan GrangerNo ratings yet

- How Does The Comparative Study of Richard III and Looking For Richard Bring To The Fore Ideas About The Human Nature and Our Desire For PowerDocument1 pageHow Does The Comparative Study of Richard III and Looking For Richard Bring To The Fore Ideas About The Human Nature and Our Desire For PowerTerence FongNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in The Crucible by Arthur MillerDocument4 pagesSymbolism in The Crucible by Arthur MillerLord VanderbiltNo ratings yet

- Act Four Student Packet (1/3)Document1 pageAct Four Student Packet (1/3)abeerwinkleNo ratings yet

- A Kestrel For A Knave Barry Hines: GCSE English Literature For AQA Specification A Resource SheetsDocument16 pagesA Kestrel For A Knave Barry Hines: GCSE English Literature For AQA Specification A Resource SheetsLance RamlalNo ratings yet

- The Hero Tells His Name (Odysseus Od. 9)Document14 pagesThe Hero Tells His Name (Odysseus Od. 9)Renato FO RomanoNo ratings yet

- Old Man Enormous Wings PDFDocument2 pagesOld Man Enormous Wings PDFGumilang0% (1)

- Pakistani Companies and Their CSR ActivitiesDocument15 pagesPakistani Companies and Their CSR ActivitiesTayyaba Ehtisham100% (1)

- Mid-Term Quiz Sample AnswersDocument4 pagesMid-Term Quiz Sample AnswersNamNo ratings yet

- George Orwell (Pseudonym of Eric Arthur Blair) (1903-1950)Document10 pagesGeorge Orwell (Pseudonym of Eric Arthur Blair) (1903-1950)Isha TrakruNo ratings yet

- 2024 JanuaryDocument9 pages2024 Januaryedgardo61taurusNo ratings yet

- IJBMT Oct-2011Document444 pagesIJBMT Oct-2011Dr. Engr. Md Mamunur RashidNo ratings yet

- Pilot Registration Process OverviewDocument48 pagesPilot Registration Process OverviewMohit DasNo ratings yet

- Ngulchu Thogme Zangpo - The Thirty-Seven Bodhisattva PracticesDocument184 pagesNgulchu Thogme Zangpo - The Thirty-Seven Bodhisattva PracticesMario Galle MNo ratings yet

- Vedic MythologyDocument4 pagesVedic MythologyDaniel MonteiroNo ratings yet

- ePass for Essential Travel Between Andhra Pradesh and OdishaDocument1 pageePass for Essential Travel Between Andhra Pradesh and OdishaganeshNo ratings yet

- Airport Solutions Brochure Web 20170303Document6 pagesAirport Solutions Brochure Web 20170303zhreniNo ratings yet

- Controlled Chaos in Joseph Heller's Catch-22Document5 pagesControlled Chaos in Joseph Heller's Catch-22OliverNo ratings yet

- Who Am I Assignment InstructionsDocument2 pagesWho Am I Assignment Instructionslucassleights 1No ratings yet

- SEO Content Template:: Recent RecommendationsDocument3 pagesSEO Content Template:: Recent RecommendationsSatish MandapetaNo ratings yet

- Hamilton EssayDocument4 pagesHamilton Essayapi-463125709No ratings yet

- Detailed Project Report Bread Making Unit Under Pmfme SchemeDocument26 pagesDetailed Project Report Bread Making Unit Under Pmfme SchemeMohammed hassenNo ratings yet

- Flexible Learning Part 1Document10 pagesFlexible Learning Part 1John Lex Sabines IgloriaNo ratings yet

- Neypes VS. Ca, GR 141524 (2005)Document8 pagesNeypes VS. Ca, GR 141524 (2005)Maita Jullane DaanNo ratings yet

- Wa0010Document3 pagesWa0010BRANDO LEONARDO ROJAS ROMERONo ratings yet

- ECC Ruling on Permanent Disability Benefits OverturnedDocument2 pagesECC Ruling on Permanent Disability Benefits OverturnedmeymeyNo ratings yet

- LectureSchedule MSL711 2022Document8 pagesLectureSchedule MSL711 2022Prajapati BhavikMahendrabhaiNo ratings yet

- IiuyiuDocument2 pagesIiuyiuLudriderm ChapStickNo ratings yet

- What Is Taekwondo?Document14 pagesWhat Is Taekwondo?Josiah Salamanca SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Engineering Economy 2ed Edition: January 2018Document12 pagesEngineering Economy 2ed Edition: January 2018anup chauhanNo ratings yet

- Consent of Action by Directors in Lieu of Organizational MeetingsDocument22 pagesConsent of Action by Directors in Lieu of Organizational MeetingsDiego AntoliniNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting 1 - Cash Straight ProblemsDocument3 pagesIntermediate Accounting 1 - Cash Straight ProblemsCzarhiena SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Encyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFDocument620 pagesEncyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFRodrigo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Teaching C.S. Lewis:: A Handbook For Professors, Church Leaders, and Lewis EnthusiastsDocument30 pagesTeaching C.S. Lewis:: A Handbook For Professors, Church Leaders, and Lewis EnthusiastsAyo Abe LighthouseNo ratings yet

- Network Marketing - Money and Reward BrochureDocument24 pagesNetwork Marketing - Money and Reward BrochureMunkhbold ShagdarNo ratings yet

- Sunway Berhad (F) Part 2 (Page 97-189)Document93 pagesSunway Berhad (F) Part 2 (Page 97-189)qeylazatiey93_598514100% (1)

- 20% DEVELOPMENT UTILIZATION FOR FY 2021Document2 pages20% DEVELOPMENT UTILIZATION FOR FY 2021edvince mickael bagunas sinonNo ratings yet

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesFrom EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1631)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- The War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesFrom EverandThe War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (273)

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessFrom EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (456)

- SUMMARY: So Good They Can't Ignore You (UNOFFICIAL SUMMARY: Lesson from Cal Newport)From EverandSUMMARY: So Good They Can't Ignore You (UNOFFICIAL SUMMARY: Lesson from Cal Newport)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsFrom EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (708)

- Can't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsFrom EverandCan't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (382)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessFrom EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessNo ratings yet

- Make It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningFrom EverandMake It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (55)

- Summary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosFrom EverandSummary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (294)

- How To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryFrom EverandHow To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (555)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Summary of Slow Productivity by Cal Newport: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without BurnoutFrom EverandSummary of Slow Productivity by Cal Newport: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without BurnoutRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Summary of Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg: How to Unlock the Secret Language of ConnectionFrom EverandSummary of Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg: How to Unlock the Secret Language of ConnectionNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsFrom EverandSummary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsNo ratings yet

- Essentialism by Greg McKeown - Book Summary: The Disciplined Pursuit of LessFrom EverandEssentialism by Greg McKeown - Book Summary: The Disciplined Pursuit of LessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (187)

- We Were the Lucky Ones: by Georgia Hunter | Conversation StartersFrom EverandWe Were the Lucky Ones: by Georgia Hunter | Conversation StartersNo ratings yet

- Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett, Dave Evans - Book Summary: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful LifeFrom EverandDesigning Your Life by Bill Burnett, Dave Evans - Book Summary: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (61)

- Summary of Bad Therapy by Abigail Shrier: Why the Kids Aren't Growing UpFrom EverandSummary of Bad Therapy by Abigail Shrier: Why the Kids Aren't Growing UpRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Book Summary of The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark MansonFrom EverandBook Summary of The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark MansonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (577)

- The 5 Second Rule by Mel Robbins - Book Summary: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageFrom EverandThe 5 Second Rule by Mel Robbins - Book Summary: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (329)

- Steal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon - Book Summary: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being CreativeFrom EverandSteal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon - Book Summary: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being CreativeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (128)

- Summary of Atomic Habits by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits by James ClearRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (168)

- Crucial Conversations by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler - Book Summary: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are HighFrom EverandCrucial Conversations by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler - Book Summary: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are HighRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- The Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, PhD. - Book Summary: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing MindFrom EverandThe Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, PhD. - Book Summary: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (57)

- Blink by Malcolm Gladwell - Book Summary: The Power of Thinking Without ThinkingFrom EverandBlink by Malcolm Gladwell - Book Summary: The Power of Thinking Without ThinkingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (114)

- Summary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursFrom EverandSummary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursNo ratings yet

- Psycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz - Book SummaryFrom EverandPsycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz - Book SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (91)