Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antisthenes

Uploaded by

Valentin MateiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antisthenes

Uploaded by

Valentin MateiCopyright:

Available Formats

Antisthenes

2 Philosophy

For other people named Antisthenes, see Antisthenes

(disambiguation).

Antisthenes (/ntsniz/;[1] Greek: ; c.

445 c. 365 BC) was a Greek philosopher and a pupil

of Socrates. Antisthenes rst learned rhetoric under

Gorgias before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates.

He adopted and developed the ethical side of Socrates

teachings, advocating an ascetic life lived in accordance

with virtue. Later writers regarded him as the founder of

Cynic philosophy.

Life

Antisthenes was born c. 445 BC and was the son of Antisthenes, an Athenian. His mother was a Thracian.[2] In

his youth he fought at Tanagra (426 BC), and was a disciple rst of Gorgias, and then of Socrates, at whose death

he was present.[3] He never forgave his masters persecutors, and is said to have been instrumental in procuring their punishment.[4] He survived the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC), as he is reported to have compared the victory of the Thebans to a set of schoolboys beating their

master.[5] Although one source tells us that he died at the

age of 70,[6] he was apparently still alive in 366 BC,[7]

and he must have been nearer to 80 years old when he

died at Athens, c. 365 BC. He is said to have lectured

at the Cynosarges,[8] a gymnasium for the use of Athenians born of foreign mothers, near the temple of Heracles.

Diogenes Lartius says that his works lled ten volumes,

but of these, only fragments remain. His favourite style

seems to have been dialogues, some of them being vehement attacks on his contemporaries, as on Alcibiades in

the second of his two works entitled Cyrus, on Gorgias

in his Archelaus and on Plato in his Satho.[9] His style

was pure and elegant, and Theopompus even said that

Plato stole from him many of his thoughts.[10] Cicero, after reading some works by Antisthenes, found his works

pleasing and called him a man more intelligent than

learned.[11] He possessed considerable powers of wit and

sarcasm, and was fond of playing upon words; saying, for

instance, that he would rather fall among crows (korakes)

than atterers (kolakes), for the one devour the dead, but

the other the living.[12] Two declamations have survived,

named Ajax and Odysseus, which are purely rhetorical.

Antisthenes nickname was the (Absolute)

(, Diog.Laert.6.13) [13][14][15]

Marble bust of Antisthenes based on the same original (British

Museum)

2.1 According to Diogenes Laertius

In his Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes

Laertius lists the following as the favorite themes of Antisthenes: He would prove that virtue can be taught; and

that nobility belongs to none other than the virtuous. And

he held virtue to be sucient in itself to ensure happiness, since it needed nothing else except the strength of

a Socrates. And he maintained that virtue is an aair of

deeds and does not need a store of words or learning; that

the wise man is self-sucing, for all the goods of others

are his; that ill repute is a good thing and much the same

as pain; that the wise man will be guided in his public acts

not by the established laws but by the law of virtue; that he

will also marry in order to have children from union with

the handsomest women; furthermore that he will not dis-

Dog

4 NOTES

dain to love, for only the wise man knows who are worthy

to be loved.[16]

2.2

Ethics

Antisthenes was a pupil of Socrates, from whom he imbibed the fundamental ethical precept that virtue, not

pleasure, is the end of existence. Everything that the

wise person does, Antisthenes said, conforms to perfect

virtue,[17] and pleasure is not only unnecessary, but a positive evil. He is reported to have held pain[18] and even illrepute (Greek: )[19] to be blessings, and said that

I'd rather be mad than feel pleasure.[20] It is, however,

probable that he did not consider all pleasure worthless,

but only that which results from the gratication of sensual or articial desires, for we nd him praising the pleasures which spring from out of ones soul,[21] and the enjoyments of a wisely chosen friendship.[22] The supreme

good he placed in a life lived according to virtue, virtue

consisting in action, which when obtained is never lost,

and exempts the wise person from error.[23] It is closely

connected with reason, but to enable it to develop itself in

action, and to be sucient for happiness, it requires the

aid of Socratic strength (Greek: ).[17]

Antisthenes, part of a fresco in the National University of Athens.

2.3

Physics

His work on Natural Philosophy (the Physicus) contained

a theory of the nature of the gods, in which he argued

that there were many gods believed in by the people, but

only one natural God.[24] He also said that God resembles

nothing on earth, and therefore could not be understood

from any representation.[25]

2.4

Logic

followers the Antistheneans,[26] but makes no reference to Cynicism.[29] There are many later tales about

the infamous Cynic Diogenes of Sinope dogging Antisthenes footsteps and becoming his faithful hound,[30]

but it is no means certain that the two men ever met.

Some scholars, drawing on the discovery of defaced coins

from Sinope dating from the period 350-340 BC, believe

that Diogenes only moved to Athens after the death of

Antisthenes,[31] and it has been argued that the stories

linking Antisthenes to Diogenes were invented by the

Stoics in a later period in order to provide a succession

linking Socrates to Zeno, via Antisthenes, Diogenes, and

Crates.[32] These tales were important to the Stoics for

establishing a chain of teaching that ran from Socrates to

Zeno.[33] Others argue that the evidence from the coins

is weak, and thus Diogenes could have moved to Athens

well before 340 BC.[34] It is also possible that Diogenes

visited Athens and Antisthenes before his exile, and returned to Sinope.[31]

In logic, Antisthenes was troubled by the problem of universals. As a proper nominalist, he held that denition

and predication are either false or tautological, since we

can only say that every individual is what it is, and can

give no more than a description of its qualities, e. g. that

silver is like tin in colour.[26] Thus he disbelieved the Platonic system of Ideas. A horse, said Antisthenes, I can

see, but horsehood I cannot see.[27] Denition is merely Antisthenes certainly adopted a rigorous ascetic

[35]

and he developed many of the principles

a circuitous method of stating an identity: a tree is a veg- lifestyle,

etable growth is logically no more than a tree is a tree. of Cynic philosophy which became an inspiration for

Diogenes and later Cynics. It was said that he had laid the

foundations of the city which they afterwards built.[36]

Antisthenes and the Cynics

4 Notes

In later times, Antisthenes came to be seen as the founder

of the Cynics, but it is by no means certain that he would

have recognized the term. Aristotle, writing a generation later refers several times to Antisthenes[28] and his

[1] Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th

edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

[2] Suda, Antisthenes.; Diogenes Lartius, vi. 1

[31] Long 1996, page 45

[3] Plato, Phaedo, 59b.

[32] Dudley 1937, pages 2-4

[4] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 9

[33] Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, page 100

[5] Plutarch, Lycurgus, 30.

[34] Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, pages 34, 112-3

[6] Eudocia, Violarium, 96

[35] Xenophon, Symposium, iv. 3444.

[7] Diodorus Siculus, xv. 76.4

[36] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 15

[8] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 13

[9] Athenaeus, v. 220c-e

5 References

[10] Athenaeus, xi. 508c-d

[11] " , mihi sic placuit ut cetera Antisthenis, hominis

acuti magis quam eruditi." Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum,

Book XII, Letter 38, section 2. In English translation:

Books four () and ve () of Cyrus I found as pleasing as the others composed by Antisthenes, he is a man

who is sharp rather than learned.

[12] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 4

[13] Susan Prince, Dept. of Classics, University of Colorado,

Boulder review of LE. Navia - Antisthenes of Athens: Setting the World Aright. Westport: Greenwood Press, Pp.

xii, 176. ISBN 0-313-31672-4 Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2001.06.23 [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

[14] The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 1 Routledge, 16 Dec 2003 (edited by FN. Magill)

ISBN 1135457409 [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

[15] H George Judge, R Blake - World history, Volume 1 Oxford University Press, 1988 [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

[16] Diogenes Lartius, Book VI. Chapter 1, 10

[17] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 11

[18] Julian, Oration, 6.181b

[19] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 3, 7

[20] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 3

[21] Xenophon, Symposium, iv. 41.

[22] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 12

[23] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 1112, 104105

[24] Cicero, De Natura Deorum, i. 13.

[25] Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, v.

[26] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1043b24

[27] Simplicius, in Arist. Cat. 208, 28

[28] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1024b26; Rhetoric, 1407a9; Topics, 104b21; Politics, 1284a15

Dudley, Donald R. (1937), A History of Cynicism

from Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D.. Cambridge

Long, A. A. (1996), The Socratic Tradition: Diogenes, Crates, and Hellenistic Ethics, in Bracht

Branham, R.; Goulet-Caze Marie-Odile, The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy.

University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-216458

Luis E. Navia, (2005), Diogenes The Cynic: The

War Against The World. Humanity Books. ISBN

1-59102-320-3

6 Further reading

Branham, R. Bracht; Caz, Marie-Odile Goulet,

eds. (1996). The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in

Antiquity and Its Legacy. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Guthrie, William Keith Chambers (1969). The

Fifth-Century Enlightenment. A History of Greek

Philosophy 3. London: Cambridge University

Press.

Navia, Luis E. (2001). Antisthenes of Athens: Setting the World Aright. Contributions in philosophy

80. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-31331672-4.

Navia, Luis E. (1996). Classical Cynicism: A Critical

Study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Navia, Luis E. (1995). The Philosophy of Cynicism

An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Rankin, H.D. (1986). Anthisthenes Sokratikos. Amsterdam: A.M. Hakkert. ISBN 90-256-0896-5.

[29] Long 1996, page 32

Rankin, H.D. (1983). Sophists, Socratics, and Cynics. London: Croom Helm.

[30] Diogenes Lartius, vi. 6, 18, 21; Dio Chrysostom, Orations, viii. 14; Aelian, x. 16; Stobaeus, Florilegium,

13.19

Sayre, Farrand (1948). Antisthenes the Socratic.

The Classical Journal 43: 237244.

External links

Antisthenes entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of

Philosophy

Lives & Writings on the Cynics, directory of literary

references to Ancient Cynics

Diogenes Lartius, Life of Antisthenes, translated by

Robert Drew Hicks (1925).

Xenophon, Symposium, Book IV

EXTERNAL LINKS

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

8.1

Text

Antisthenes Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisthenes?oldid=658211636 Contributors: Arvindn, Delirium, Wetman, Owen, Robbot, ChrisO~enwiki, Fabiform, Berasategui, Alensha, Jastrow, Pgan002, Antandrus, Tothebarricades.tk, Bodnotbod, Karl-Henner, ElAhrairah, Lucidish, Bender235, El C, Brisis~enwiki, Art LaPella, Robotje, Pwqn, Nuno Tavares, Silverwood, Rachel1, Yurik, AllanBz,

Rjwilmsi, FlaBot, Jaraalbe, DVdm, YurikBot, RussBot, Jimphilos, Dast, Olen Watson, Funkendub, SmackBot, Cessator, Hmains, Makemi,

InedibleHulk, Eastlaw, Gregbard, Cydebot, Steel, Thijs!bot, Massimo Macconi, Igorwindsor~enwiki, Waerloeg, Deective, Magioladitis,

Kutu su~enwiki, Nikolaj Christensen, CCS81, Crvst, Yonidebot, RB972, VolkovBot, Amikake3, Philip Trueman, TXiKiBoT, A4bot, AlleborgoBot, SieBot, Jaksap, Gerakibot, Loveless2, Keilana, Shakko, Surferhere, Myrvin, PipepBot, Singinglemon~enwiki, Excirial, Chronicler~enwiki, RogDel, Mizpah14, Kbdankbot, Addbot, 15lsoucy, Nathan.besteman, Lightbot, Luckas-bot, Yobot, J04n, GrouchoBot, Omnipaedista, DefaultsortBot, RedBot, , TobeBot, Oracleofottawa, 777sms, RjwilmsiBot, EmausBot, WikitanvirBot, J. Clef, ZroBot,

Chewings72, ChuispastonBot, EauLibrarian, Widr, Helpful Pixie Bot, Pasicles, Vanished user sdij4rtltkjasdk3, Xenxax, Whalestate and

Anonymous: 41

8.2

Images

File:Anisthenes_Pio-Clementino_Inv288.jpg

Source:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ce/Anisthenes_

Pio-Clementino_Inv288.jpg License: CC BY 3.0 Contributors: Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009) Original artist: ?

File:Antisthenes_BM_1838.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5a/Antisthenes_BM_1838.jpg License:

Public domain Contributors: Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011) Original artist: Unknown

File:Antisthenes_Lebiedzki_Rahl.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/39/Antisthenes_Lebiedzki_Rahl.

jpg License: Public domain Contributors: http://nibiryukov.narod.ru/nb_pinacoteca/nbe_pinacoteca_artists_l.htm Original artist: Eduard

Lebiedzki, after a design by Carl Rahl

File:Commons-logo.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/4a/Commons-logo.svg License: ? Contributors: ? Original

artist: ?

File:Folder_Hexagonal_Icon.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/48/Folder_Hexagonal_Icon.svg License: Cc-bysa-3.0 Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

File:People_icon.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/37/People_icon.svg License: CC0 Contributors: OpenClipart Original artist: OpenClipart

File:Portal-puzzle.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/f/fd/Portal-puzzle.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ?

Original artist: ?

File:Wikiquote-logo.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/Wikiquote-logo.svg License: Public domain

Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

8.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

You might also like

- Cain, Shame and Ambiguity in Platos GorgiasDocument27 pagesCain, Shame and Ambiguity in Platos GorgiasmartinforcinitiNo ratings yet

- Two Rival Conceptions of SôphrosunêDocument16 pagesTwo Rival Conceptions of SôphrosunêMaria SozopoulouNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Genealogy of MoralsDocument68 pagesNotes On The Genealogy of MoralsPaula LNo ratings yet

- Woodruff Thucydides On Justice Power and Human Nature Pp.39 58Document12 pagesWoodruff Thucydides On Justice Power and Human Nature Pp.39 58Emily FaireyNo ratings yet

- The Derveni Papyrus: An Interim TextDocument63 pagesThe Derveni Papyrus: An Interim TextРужа ПоповаNo ratings yet

- Foucault Discourse and Truth - The Problematization of Parrhesia (Berkeley, 1983) PDFDocument66 pagesFoucault Discourse and Truth - The Problematization of Parrhesia (Berkeley, 1983) PDFDarek Sikorski100% (1)

- Images in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and ThoughtFrom EverandImages in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Protreptic and Biography PDFDocument7 pagesProtreptic and Biography PDFIonut MihaiNo ratings yet

- Philodemus de Signis An Important Ancien PDFDocument11 pagesPhilodemus de Signis An Important Ancien PDFcabottoneNo ratings yet

- (Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis) Tryggve Göransson - Albinus, Alcinous, Arius Didymus (1995) PDFDocument128 pages(Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis) Tryggve Göransson - Albinus, Alcinous, Arius Didymus (1995) PDFMarcos EstevamNo ratings yet

- Asmis Philodemus' EpicureanismDocument38 pagesAsmis Philodemus' EpicureanismRobert Pilsner100% (1)

- Books I - VI PDFDocument206 pagesBooks I - VI PDFjefferson fosecaNo ratings yet

- Hesiod (Paley 1883) PDFDocument402 pagesHesiod (Paley 1883) PDFJames BlondNo ratings yet

- Aristotle - Parts of Animals Movement of Animals Progression of Animals (Greek - English)Document562 pagesAristotle - Parts of Animals Movement of Animals Progression of Animals (Greek - English)Sebastian Castañeda PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Phaedo: Plato (Translator: Benjamin Jowett)Document48 pagesPhaedo: Plato (Translator: Benjamin Jowett)SqunkleNo ratings yet

- Derrida Plato PhaedrusDocument13 pagesDerrida Plato PhaedrusAphro GNo ratings yet

- The Sophists by George Briscoe Kerferd (HTTP://WWW - Martinfrost.ws/htmlfiles/sophists - Html#solo)Document16 pagesThe Sophists by George Briscoe Kerferd (HTTP://WWW - Martinfrost.ws/htmlfiles/sophists - Html#solo)Librairie IneffableNo ratings yet

- Prosodic Words: Sharon PeperkampDocument6 pagesProsodic Words: Sharon PeperkampTwana1No ratings yet

- Future Continuous and PeerfectDocument3 pagesFuture Continuous and PeerfectangieNo ratings yet

- Early Latin Secular SongDocument10 pagesEarly Latin Secular SongPaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- The Unity of Platos Thought 1000042573 PDFDocument96 pagesThe Unity of Platos Thought 1000042573 PDFkrstodemNo ratings yet

- Slater, Niall W.-Voice and Voices in Antiquity-Brill (2016)Document456 pagesSlater, Niall W.-Voice and Voices in Antiquity-Brill (2016)Pablo Routier Abbet100% (1)

- Article ASMIS - Seneca's On The Happy Life - Apeiron 23 (1990)Document38 pagesArticle ASMIS - Seneca's On The Happy Life - Apeiron 23 (1990)VelveretNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Companion To Seneca The Seneca PDFDocument13 pagesCambridge Companion To Seneca The Seneca PDFAndyPony31No ratings yet

- Johan Nicolai Madvig, Marcus Tullius Cicero - Cicero, de Finibus Bonorum Et Malorum - Libri Quinque (2010, Cambridge University Press)Document538 pagesJohan Nicolai Madvig, Marcus Tullius Cicero - Cicero, de Finibus Bonorum Et Malorum - Libri Quinque (2010, Cambridge University Press)m8rcjndgxNo ratings yet

- The Unwritten Doctrines, Plato's Answer To SpeusippusDocument23 pagesThe Unwritten Doctrines, Plato's Answer To SpeusippusafterragnarokNo ratings yet

- Reincarnare OrfismDocument14 pagesReincarnare OrfismButnaru Ana100% (1)

- The Speech of Alcibiades in TheDocument9 pagesThe Speech of Alcibiades in Theramonsito123No ratings yet

- The History of The History of Philosophy and The Lost Biographical TraditionDocument8 pagesThe History of The History of Philosophy and The Lost Biographical Traditionlotsoflemon100% (1)

- Classroom Expressions 1Document7 pagesClassroom Expressions 1Reuel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Geert Roskam-A Commentary On Plutarch's de Latenter Vivendo - Leuven Univ PR (2007)Document279 pagesGeert Roskam-A Commentary On Plutarch's de Latenter Vivendo - Leuven Univ PR (2007)Cristea100% (1)

- Herodotus On TyrannyDocument15 pagesHerodotus On TyrannyqufangzhengNo ratings yet

- Havelock, E. A. - Dikaiosune. An Essay in Greek Intellectual History - Phoenix, 23, 1 - 1969!49!70Document23 pagesHavelock, E. A. - Dikaiosune. An Essay in Greek Intellectual History - Phoenix, 23, 1 - 1969!49!70the gatheringNo ratings yet

- Gagarin The Truth of Antiphons TruthDocument10 pagesGagarin The Truth of Antiphons Truthasd asdNo ratings yet

- Aristotle in Byzantium: Klaus OehlerDocument14 pagesAristotle in Byzantium: Klaus OehlerMihai FaurNo ratings yet

- Early Greek Philosophy PDFDocument7 pagesEarly Greek Philosophy PDFШолпанКулжанNo ratings yet

- Zeller Eduard - Socrates-And-The-Socratic-Schools PDFDocument448 pagesZeller Eduard - Socrates-And-The-Socratic-Schools PDFishmailpwquod100% (1)

- Ovid TextsDocument2 pagesOvid TextsPatriBronchalesNo ratings yet

- Lucian's Dialogues of The Gods - Hayes and Nimis (March 2015) PDFDocument166 pagesLucian's Dialogues of The Gods - Hayes and Nimis (March 2015) PDFuriz1No ratings yet

- Labile Verbs in Late Latin: 1 IntroductionDocument58 pagesLabile Verbs in Late Latin: 1 Introductionкирилл кичигинNo ratings yet

- Plato S Influence On Gerogios Gemistos PDocument20 pagesPlato S Influence On Gerogios Gemistos PtreebeardsixteensNo ratings yet

- Cicero: Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, M.ADocument258 pagesCicero: Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, M.AGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Studies of Platos Philebus A BibliographDocument10 pagesStudies of Platos Philebus A Bibliographkaspar4No ratings yet

- Composition of Photius' BibliothecaDocument5 pagesComposition of Photius' BibliothecaDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Initial Test 1º ESO 2014-15Document4 pagesInitial Test 1º ESO 2014-15EsterNo ratings yet

- Xenoanabasis 13july18w PDFDocument189 pagesXenoanabasis 13july18w PDFuriz1No ratings yet

- Gottschalk Anaximander's ApeironDocument18 pagesGottschalk Anaximander's ApeironValentina MurrocuNo ratings yet

- Psychagogia in Plato's PhaedrusDocument20 pagesPsychagogia in Plato's PhaedrusAlba MarínNo ratings yet

- Dionysius Longinus - On The SublimeDocument446 pagesDionysius Longinus - On The SublimenoelpaulNo ratings yet

- Greek Philosophy, London Study Guide Biblio 2005Document24 pagesGreek Philosophy, London Study Guide Biblio 2005MeatredNo ratings yet

- Horace and His Influence by Showerman, GrantDocument71 pagesHorace and His Influence by Showerman, GrantGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Consequences LiteracyDocument43 pagesConsequences Literacysilvana_seabraNo ratings yet

- Descartes Plato and The Cave Stephen Buckle Philosophy JournalDocument38 pagesDescartes Plato and The Cave Stephen Buckle Philosophy JournalglynndaviesNo ratings yet

- The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, GentlemanDocument918 pagesThe Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, GentlemanRaluca VijeleaNo ratings yet

- DemocritusDocument3 pagesDemocritusDaniel0% (2)

- Diogenes of SinopeDocument26 pagesDiogenes of SinopeKent Malig-onNo ratings yet

- Diogenes of SinopeDocument10 pagesDiogenes of SinopeValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- John IPHP PT 1Document12 pagesJohn IPHP PT 1Erica SamoragaNo ratings yet

- Vera FignerDocument3 pagesVera FignerValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Walther Rathenau - WikipediaDocument9 pagesWalther Rathenau - WikipediaValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- VitruviusDocument9 pagesVitruviusValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Illuminated ManuscriptDocument8 pagesIlluminated ManuscriptValentin Matei100% (1)

- Thal Ass OcracyDocument3 pagesThal Ass OcracyValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Narodnaya VolyaDocument4 pagesNarodnaya VolyaValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Radu I of WallachiaDocument3 pagesRadu I of WallachiaValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Zamfir ArboreDocument15 pagesZamfir ArboreValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- CuneiformDocument11 pagesCuneiformValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Duiliu ZamfirescuDocument6 pagesDuiliu ZamfirescuValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- People's Party (Interwar Romania)Document19 pagesPeople's Party (Interwar Romania)Valentin MateiNo ratings yet

- François GuizotDocument8 pagesFrançois GuizotValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Spat Ha RiosDocument3 pagesSpat Ha RiosValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Nihilist MovementDocument4 pagesNihilist MovementValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- History of Persian DomesDocument7 pagesHistory of Persian DomesValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Alexis NourDocument9 pagesAlexis NourValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- JunimeaDocument5 pagesJunimeaValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Nicolae IorgaDocument41 pagesNicolae IorgaValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Ștefan ZeletinDocument4 pagesȘtefan ZeletinValentin Matei100% (1)

- Personal Is MDocument6 pagesPersonal Is MValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Iranian PhilosophyDocument6 pagesIranian PhilosophyValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Mihail ManoilescuDocument7 pagesMihail ManoilescuValentin Matei100% (1)

- Jacob ThompsonDocument3 pagesJacob ThompsonValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Alcibiades DeBlancDocument3 pagesAlcibiades DeBlancValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Adam MüllerDocument4 pagesAdam MüllerValentin Matei100% (1)

- Crusade of RomanianismDocument9 pagesCrusade of RomanianismValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- New Departure (Democrats)Document3 pagesNew Departure (Democrats)Valentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Guerrilla Warfare in The American Civil WarDocument4 pagesGuerrilla Warfare in The American Civil WarValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Alcibiades DeBlancDocument3 pagesAlcibiades DeBlancValentin MateiNo ratings yet

- Complete The Form Below. Write No More Than Three Words And/Or A Number For Each AnswerDocument4 pagesComplete The Form Below. Write No More Than Three Words And/Or A Number For Each AnswerCooperative LearningNo ratings yet

- Decentering The Ego-Self and Releasing The Care-ConsciousnessDocument14 pagesDecentering The Ego-Self and Releasing The Care-ConsciousnessFille e BeauNo ratings yet

- School Form Checking Report SFCRDocument10 pagesSchool Form Checking Report SFCRRene Rey B. SulapasNo ratings yet

- The CarpenterDocument10 pagesThe CarpenterSukanya V. MohanNo ratings yet

- Nebosh: Management of Health and Safety Unit Ig1Document5 pagesNebosh: Management of Health and Safety Unit Ig1shaynad binsharaf100% (3)

- Progress Check Practice Revisi N Del Intento PDFDocument7 pagesProgress Check Practice Revisi N Del Intento PDFYordy Rodolfo Delgado Rosario100% (1)

- Moral LeadersDocument3 pagesMoral LeadersKeab Sun YatsunNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Law Entrance Exams SyllabusDocument3 pagesFaculty of Law Entrance Exams Syllabussana khanNo ratings yet

- Essay 21: Road Safety: Thanh Ha NguyenDocument2 pagesEssay 21: Road Safety: Thanh Ha Nguyenqbich37No ratings yet

- Juristic PersonDocument3 pagesJuristic Personpoonam kumariNo ratings yet

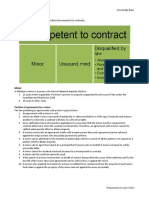

- Competency To Contract: MinorDocument4 pagesCompetency To Contract: MinorZeeshan BakaliNo ratings yet

- MotherDocument3 pagesMotherDaisy Jade Mendoza DatoNo ratings yet

- SUMSEM-2021-22 HUM1022 ETH VL2021220701716 DA-1 QP KEY F1 F2 Digital Assignment I HUM1022Document4 pagesSUMSEM-2021-22 HUM1022 ETH VL2021220701716 DA-1 QP KEY F1 F2 Digital Assignment I HUM1022Nathan ShankarNo ratings yet

- MK Gandhi and Indian Democr̥acyDocument7 pagesMK Gandhi and Indian Democr̥acyAminesh GogoiNo ratings yet

- Asdaf Kabupaten Nunukan, Provinsi Kalimantan Utara Program Studi Kependudukan Dan Pencatatan SipilDocument9 pagesAsdaf Kabupaten Nunukan, Provinsi Kalimantan Utara Program Studi Kependudukan Dan Pencatatan SipilFatimah AzahraNo ratings yet

- 20230417-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Katie O'Bryan & Paula Gerber-Re Voice, Etc-Supplement 1Document2 pages20230417-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Katie O'Bryan & Paula Gerber-Re Voice, Etc-Supplement 1Gerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- PhilosophyDocument7 pagesPhilosophyJessa Mae A. EstinopoNo ratings yet

- Term 2 WorksheetDocument5 pagesTerm 2 WorksheetSaravanna . B. K 8 C VVPNo ratings yet

- 01-Approaches To StrategyDocument24 pages01-Approaches To StrategyDimuthuSuranjanaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On Different Leadership Approach Analysis Based On Shabnam RamaswamyDocument37 pagesTerm Paper On Different Leadership Approach Analysis Based On Shabnam RamaswamySamia IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Contract Law Mock Examination: Date: Time Allowed: One HourDocument6 pagesContract Law Mock Examination: Date: Time Allowed: One Hourfaieza hussainNo ratings yet

- Signs You - Re in A Toxic RelationshipDocument6 pagesSigns You - Re in A Toxic RelationshipJustice Anunaobi100% (1)

- SMS Standard SM 0001 Issue B - 20220331Document149 pagesSMS Standard SM 0001 Issue B - 20220331allfromturkey.aeNo ratings yet

- Role in The SocietyDocument1 pageRole in The SocietyChristian VillaNo ratings yet

- The 19 Century Philippines: Changes in Its Designated AspectsDocument4 pagesThe 19 Century Philippines: Changes in Its Designated AspectsMarvic AboNo ratings yet

- The Fifty-Seven Precepts of ZoteDocument4 pagesThe Fifty-Seven Precepts of ZoteJohn WickNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE VII (Architect's Credo)Document1 pageARTICLE VII (Architect's Credo)RuzelAmpo-anNo ratings yet

- Candida As A Domestic ComedyDocument2 pagesCandida As A Domestic ComedyAnjan Some0% (2)

- Baumrind 1964Document3 pagesBaumrind 1964mylightstarNo ratings yet

- Jean-Paul Sartre - Republic of SilenceDocument2 pagesJean-Paul Sartre - Republic of SilenceLaletraqNo ratings yet