Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parol Evidence Rule

Uploaded by

Nur Farhana AnaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parol Evidence Rule

Uploaded by

Nur Farhana AnaCopyright:

Available Formats

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

INTRODUCTION

According to Sir Frederick Pollock, a contract can be defined as:

A promise or set of promises which the law will enforce.

A contract intends to formalize an agreement between two or more parties, in

relation to a particular subject. Contracts can cover an extremely broad range of

matters, including the sale of goods or real property, and the terms of employment or of

an independent contractor relationship 1. Since the law of contracts is at the heart of

most business dealings, it is the vital areas of legal concern and can engage variations

on situation and complexities.

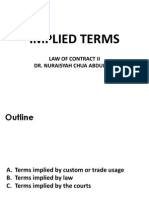

Terms in a contract set out legal duties of each party under that agreement. They

can be either in express or implied terms. The terms of a contract may be wholly oral,

wholly written, partly oral and partly written.

If contract is put down in writing, the statement is regarded as the term of

contract and any prior oral statement will usually be regarded as a representation as

they are not included in the contract, on the assumption that they are less important. 2

Besides, the existence of signature in the contract will regularly make it complicated for

the signatory to successfully argue that the statements made do not represent the

intention of the parties.3

1 Legal Dictionary, Thefreedictionay.com

2 Emily M. Weitzenbeck. (2012). Norwegian Research Center for Computers & Law.

University of Oslo.

3 Ibid

1

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

This was established in the case of L Estrange v F Graucob Ltd4 where the court

held that he plaintiff was bound by her signature in the agreement even though she

claimed that she does not read the term carefully. It means here that so long as the

party signed the contract, total lack of awareness on the part of the plaintiff is irrelevant.

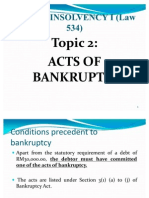

There comes the existence of parol evidence rule to support the above statement

made that any extrinsic evidences cannot be brought into the court unless the document

itself. Essentially, the rule aims to protect the original contents of the written contract

which will contribute to maintaining certainty and stability; particularly in business

dealings.5 The parol evidence rule is found under common law and in Malaysia is

provided in Section 91 and 92 of the Evidence Act 1950. 6

The general rule of Section 91 of the parol evidence rule is to prohibit any kind of

oral evidences where the terms of the contract have been put into writing. 7 It means,

when there is written contract, any other evidences which are not stated in the

document are not acceptable to be brought into the court if there are breach of terms of

contract.

On the other hand, Section 92 of Evidence Act 1950 provides that when the the

terms have been prove as in Section 91, any oral agreement or statement shall not be

4 [1934] 2 KB 394.

5 Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at page

158.

6 Act 56

7Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at page 159.

2

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

admitted.8 Nevertheless, there are certain exceptions to the parol evidence rule in

Section 92 which have reduced the usefulness of the rule. The main issue here is to

which extent the oral evidences can invoke the parol evidence rule?

Besides the exceptions provided in parol evidence rule, there is collateral

contract, a device which has been used, to admit pre- contractual statements which had

not been incorporated into the written agreement. 9 Collateral contract is a separate oral

promise, exists side by side of the written contract which induces the parties to enter

into contract.10 Two general situations in which the courts may acknowledge the

existence of a collateral contract are:

a) Where a party has been able to show that it would have refused to enter into

if it did not receive assurance on a particular point; and

b) Where there was a promise not to enforce a particular term in the main

contract.11

8 Visu Sinadhurai. (2003). Law of Contract. (3 rd ed.). Butterworths (Canada)

Limitedat page 190.

9 See Haji Mohamed Akram b Shair Mohd, Concept of Collateral Contract and s 92

Evidence Act 1950 [1984] 1 MLJ clxix. See generally Power-Smith, Vincent, Collateral

Warranties and the Construction Industry [1991] MLJ

xvii.

10 Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at page

162

11 Krishnan Arjunan and Abdul Majid Nabi Baksh. (2008). Contract Law in Malaysia. Malayan

Law Journal Sdn. Bhd at page 196.

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

The device of collateral contract does not offend the extrinsic evidence rule

because the oral promise is not imported into the main agreement as it comes

separately.

12

It must be noted that collateral contract exist on the basis of the written

contract itself. Thus, if the collateral contract contradicts with the written term in the

main contract, then the collateral contract overrides the inconsistent written term.

13

However, it cannot destroy the written one as it originally comes into existing because of

the written contract.14

PAROL EVIDENCE RULE

When a contract is reduced to writing, neither party can submit extrinsic evidence

to the contractual document alleging terms agreed upon but not contained in the

document. This is called as parol evidence rule. 15 It means, when two parties have

made a contract and have expressed it in a writing to which they have both assented as

the complete and accurate integration of that contract, evidence, whether parol or

otherwise, of antecedent understanding and negotiations will not be admitted for the

purpose of varying or contradicting the writing.16

12 Syed Ahmad S A Alsagoff. (1998). Principles of the law of Contract in Malaysia. (2 nd ed.).

Malayan Law journal

Sdn. Bhd at page 179.

13 Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at

page163.

14 Ibid, at page164.

15 Emily M. Weitzenbeck. (2012). Norwegian Research Center for Computers & Law.

University of Oslo.

16 Arthur L. Corbin. (1944). The parol evidence Rule, 53. Yale Law Journal.

4

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

However, under common law, there are several exceptions to the rule. For

instance, the intention that agreement is only partially written. It means here, if written

document was not intended to set out all the terms agreed between the parties, extrinsic

evidence of the other term is admissible. Secondly, extrinsic evidence is also

permissible to clarify uncertainty in express term.17

In Malaysia, the parol evidence rule is provided under Section 91 and Section 92

of the Evidence Act 1950.18 Under these sections, when the terms of the contract have

been reduced to writing, no other extrinsic evidence is admissible.

The general rule of Section 91 was clearly explained by P.B. Gajendragadkar J in

Bai Hira devi v Official Assignee, Bombay 19 when he stated as follows:

the normal rule is that the contents of a document must be proved by primary evidence which is

the document itself in original. Section 91 is based on what is sometimes described as the best

evidence rule. The best evidence about the contents of a document is the document itself and it

is the production of the document that is required by section 91 in proof of its content. In a sense,

the rule enunciated by section 91 can be said to be an exclusive rule in as much as it excludes

17 Emily M. Weitzenbeck, 2012. Norwegian Research Center for Computers & Law.

University of Oslo.

18 Act 56

19 AIR 1958 SC 448 at p 450.

5

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

the admission of oral evidence for proving the contents of the document except in cases where

secondary evidence is allowed to be led under the relevant provisions of the Evidence Act.

Thus, it can be deduced that Section 91 try to protect the original contents of the

contract in a sense that the best evidence about the contents of a document is the

document itself. Admission of oral evidence is not necessary as the document itself will

speak through its contents.20

On the other hand, Section 92 of this act stated as follows:

When the terms of any such contracthave been proved according to Section 91, no evidence of

any oral agreement or statement shall be admitted as between the parties to any such instrument

or their representatives in interest or the purpose of contradicting, varying, adding to or

subtracting from its term.21

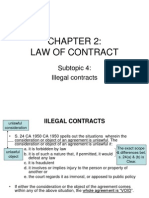

Based on the above statement, it is clear that Section 92 excludes the admission

of oral evidence for the purpose of contradicting, varying, adding to, or subtracting from

the terms of a written agreement. Nevertheless there are exceptions provided under this

section. For example, any fact which can nullify a document such as fraud, intimidation,

illegality, want of due execution, want of capacity in any contracting party, want or failure

20 Datuk Tan leng Teck v Sarjana Sdn Bhd & Ors [1997] 4 MLJ 239, 341 per

Augustine Paul JC (as he then was).

21 See Section 92 Evidence Act 1950.

6

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

of consideration and mistake in law and fact may be proved; see proviso (a) to Section

92. Besides, proviso (b) allows the access of parol evidence of the existence of any

separate oral agreement as to any matter on which the document is silent. 22

It can be seen here that exceptions provided under Section 92 actually reduce

the effectiveness of parol evidence rule. However, this rule cannot be abolished

because this is the only way to maintain the originality of the documents except few

circumstances that allow such evidences to be proved.

There are two important Federal Court decisions that have given different

interpretations to Section 92 as to when parol evidence may be admissible. 23 In Tindok

Besar Estate Sdn Bhd v Tinjar Co,24 the appellant was a contractor for extraction of

timber for a company. He later decided not to carry on with the work. An agreement was

made between the appellant and the respondent where the respondent undertook the

work of extracting timber. There was a dispute as to this agreement. Though the parties

had entered into a written agreement, the respondents attempted to introduce other

terms which they alleged had not been incorporated into the written agreement.

In this case, the Federal Court judge disagreed with the approach made by the

trial judge where the trial judge used the case of Coalfields of Burma Ltd v HH

22 For other exceptions, see the rest of provisos to Section 92.

23 Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at page

160.

24 [1979] 2 MLJ 229.

7

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

Johnson25 to be relied too without distinguished the facts that there was no written

contract in that case whereas, in the instant case there was a written agreement. The

Federal Court judge pointed out the exceptions provided in Section 92 Evidence Act

1950 to be examined carefully. However, at the same time, the Federal Court Judge

also pointed out the risk of allowing oral evidence in case where there is written

agreement, relying on the cases of Foo Tock Lim v Piong Liew26 and Siah v Tengku

Nong:27

it would be open to any party to a litigation concerning an agreement to say that the agreement

which is the subject matter of the dispute did not contain all the terms thereof and to seek to

introduce such terms or even terms which might not even have been within the contemplation of

the other party. No agreement would then be safe from being re-written by one party in a court of

law.28

Thus, after considering all the facts, Chang Min Tat FJ made a statement that the

correct view seems to be that Section 91 and 92 applies when the terms of the

agreement (not necessarily all the terms) have been reduced in writing. In such a case,

proof of the terms shall be by document itself or by secondary evidence.

29

The court

25 AIR 1925 Rang 128.

26 [1963] MLJ 67.

27 [1964] MLJ 63.

28 Above note 51, at page 223.

29 S. Santhana Dass. ( 2005). General principle of Contract Law in Malaysia. Akitiara

Corporation Sdn Bhd at page

102.

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

then considered in detailed whether the evidence brought in this case fall under the

provisos to Section 92, which then the court held that it was not.

From this Tindok Besars case, we can see the court action on dealing with the

matters contradict to parol evidence rule. The court have to examine these two sections

in very detail and careful before came to the decision. From this case; it is very difficult

for the party to contract to prove the existence of evidences that are not in writing. The

oral evidences must fall under the exceptions provided if and only if the party wants to

succeed, which is actually very hard to be established.

The later decision made by the Federal Court contrasted the decided case above

in Tan Chong & Sons Motor Co Sdn Bhd v Alan Mcknight. 30 In this case, the respondent,

an Australian national, wanted to buy a car to get the benefit of exemption from duty in

Malaysia, if the car complied with the Australian design regulations. He signed a buyers

order which contained a condition that no guarantee or warranty of any kind whatsoever

was given by the company. The respondent maintained that he only agreed to buy the

car on the representation of the appellants salesman that the car conformed to the

Australian design regulations. The car which was subsequently delivered to the

respondent did not comply with the regulations, and the respondent was successful in

recovering his losses, including loss of the fiscal advantage of importing it duty-free into

Australia.

30 [1979] 2 MLJ 229, FC.

9

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

The issue rose whether the representations of the appellant were admissible

under Section 92 Evidence Act. The court held that proviso (b) and (c) Section 92

applied.31

These two cases seem to be different based on their decisions. However, what is

matter now is that it is only when the original document has been tendered and admitted

to prove its terms or contents under Section 91, that section 92 comes into play to

exclude evidence of any oral agreement or statement for the purpose of contradicting,

varying, adding or subtracting from its terms unless it comes within the exceptions

contained in the provisos or illustrations.

32

There was another example of case which showed a strict application of parol

evidence rule. In Ng Ee v PP,33 the prosecution had to prove the seating capacity of a

vehicle. The seating capacity was required by law to be recorded in the license. The

license was not tendered in court but instead a police constable gave oral evidence to

the effect that the bus could carry 16 passengers. The court held that under Section

91, no evidence may be given in proof of the terms of such matter except the document.

For example, the license or secondary evidence of its content when secondary

evidence is admissible.

31 Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia at page

161.

32 S. Santhana Dass. ( 2005). General principle of Contract Law in Malaysia. Akitiara

Corporation Sdn Bhd at page 106.

33 [1941] MLJ 180

10

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

It means, this section only excludes oral evidence as to the terms of the contract

not to the existence of the contract. Oral evidence can be admitted to prove the

existence of the contract or where there is a plea denying the contract, oral evidence

can be admitted in support of it.34

COLLATERAL CONTRACT.

It is evident both on principle and on authority, said Lord Moulton in 1913.

Collateral contract is a written or oral agreement associated as a second, or side

contract made between the original parties, or between a third party and an original

party.35This typically occurs before or at the same time the first or main contract is

made. This collateral contract is independent and separate from the primary contract.

If there is a negotiating statement and if it is made with the reason of inducing the

other party to act on it, and it actually induces him to act on it by entering into the

contract, that is prima facie ground for inferring that the representations was projected

as a guarantee. That representation becomes part of collateral contract. 36 This is best

described by Lord Denning M.R. in Dick Bentley Productions Ltd v Harold Smith

34 Ng Kong Yue and Anor v R. [1962] MLJ 67,69; United Malayan banking Corp. Bhd v Tan

Lian Keng and Ors [1990]

1 MLJ 281 HC; Ng Kong Yue & Anor v R [1962] MLJ 67 HC;

Tyagaraja Mudaliar & Anor v Vadathanni [1936] MLJ 62

PC.

35 Blacks Law Dictionary. thelawdictionary.org.

36 Krishnan Arjunan. (2008). Contract Law in Malaysia. Malayan Law Journal Sdn

Bhd.

11

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

(Motors) Ltd37, where the statements made to induce the party to act on it and actually

induces him to act on it as being collateral.

In Kah Seng Construction Sdn Bhd v Selsin Development Sdn Bhd,38Low Hop

Bing J stated that a collateral contract comes into existence prior to or at the time of the

conclusion of the main contract. The consideration for the collateral contract is the

making of the main contract. This case cited above are strong authority for the

propositions that collateral contract is a separate pre-contract statement on the basis of

which the parties entered into a contract. 39

Under the common law, there are test laid down by the High Court in Australia in

the case of JJ savage & Sons Pty ltd v Blakney40 to determine whether the statement

made at the time when the contract was entered constitute a collateral contract. It was

held that three elements must be present:

a) The statement was intended to be relied on:

b) There was reliance by the party alleging the existence of the contract; and

c) There was an intention on the part of the maker of the statement to guarantee

its truth.

37 [1965] 2 All ER 65, 67: Approved by the FC in Tan Swee Hoe Co Ltd v Ali Hussein

Bros. [1980] 2 MLJ 16.

38 [1997] 1 CLJ Supp.488.

39 Krishnan Arjunan and Abdul Majid Nabi Baksh. (2008). Contract Law in Malaysia. Malayan

Law Journal Sdn. Bhd at page 121.

40 (1970) 119 CLR 435 HC.

12

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

The question arose whether this test is applicable in Malaysia? This was best

described in Kluang Wood products Sdn Bhd & Anor v Hong Leong Finance Berhad

and Anor41 where the trial judge held that all the three elements discussed above must

be established to prove the existence of collateral contract.

The notion of a collateral contract has long been a part of the Malaysia law of

contract as illustrated by the Federal Court decision in Tan Swee Hoe Co Ltd v Ali

Hussain Bros.42 The leading authority in Malaysia is the judgment of Raja Azlan Shah

CJ in this case.

The appellant had orally agreed to allow the respondent to occupy certain

premises for so long as they wished on payment of RM14,000 as tea money.

Subsequently, the parties entered into two agreements. Both agreements made

provisions for increase in rental. No mention was, however, made of the earlier oral

assurance in either of these two agreements. Dispute subsequently arose between the

parties, and the appellant served on the respondent a notice to quit the premises. Raja

Azlan Shah CJ stated that an oral promise, given at the time of contracting which

induces a party to enter into a contract overrides any inconsistent written agreement.

The device of collateral contract does not offend the extrinsic evidence rule because the

oral promise is not imported into the main agreement. Instead it constitutes a separate

41 [1991] 1 MLJ 193, FC.

42 [1980] 2 MLJ 16, FC.

13

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

contract which exists side by side with the main agreement. Reference was made by

the Chief Justice to Chitty on Contracts, 24th edition, para 674:

In our view there is a growing body of authority that supports the proposition that a collateral

agreement can exist side by side with the main agreement that it contradicts.

The Chief Justice also relied upon the English decisions such as J Evans & Sons v

Andrea Merzario,43and Heilbut Symons & Co v Buckleton 44 which also stated that the

collateral contract constitute a separate contract that exists side by side with main

agreement.

However, it must be taken into account that a collateral contract cannot destroy

the main written contract as it can only exist on the basis of the main agreement. In

Industrial Distribution Sdn Bhd v Golden Sands Construction Sdn Bhd,45 Visu

Sinnadurai J reiterated the principle earlier stated by Raja Azlan Shah CJ in Tan Swee

Hoe Co Ltd where the collateral contract exist aside the main contract.

It has to be noted that collateral contract only exit if there is a written agreement

made by parties to contract. It may overrides the main agreement, but not to the extent

that may destroy the main contract.

43 [1976] 2 All ER 930.

44 [1913] AC 30.

45 [1993] 3 MLJ 433, HC.

14

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

In the other hand, in order to show that oral agreement will prevail over written

agreement when it contradicts, it was best illustrated y the Privy Council in Kandasami v

Mustafa46 where the court held that there was in existence a collateral agreement under

which the parties had agreed that the written agreement would have no legal effect. 47

In a nutshell, laws applicable in Malaysia are not absurd or too rigid to be relied

on. When a person promise to someone, he must by hook or by crook be responsible

for what he said in order for justice to be upheld.

CONCLUSION

The existence of parol evidence rule in Malaysia under Section 91 and 92 of the

Evidence Act 1950 is fundamentally, to protect the original contents of the written

contract which will contribute to maintaining certainty and stability; particularly in

business dealings.

Generally, evidence may not be admissible to vary or contradict a written

agreement. However, the position is as was stated by Raja Azlan Shah (who was then

CJ) in Tan Sween Hoe & Co Ltd v Ali Husain, as follows:

46 [1983] 2 MLJ 85.

47 Visu Sinadhurai. (2003). Law of Contract. (3 rd ed.). Butterworths (Canada)

LimitedPress at page 196.

15

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

Although it is trite law that parol evidence is not admissible to add, to vary or contradict a written

agreement, a technical way of overcoming the rule is by invoking the doctrine of collateral

contract warranty. There is a growing body of authority which supports the proposition that a

collateral agreement can exist side by side with the main agreement which it contradicts.

As numerous problems arising in Malaysia especially on the business matters to prove

the existence of extrinsic evidences aside from the written contract, it would be more

appropriate to be more careful when dealing with contractual matters. Put down

everything that might subject to the contract or inducing the parties to act on it in writing

form. It will be easier to prove printed materials than proving something which is orally

agreed upon by the parties. It must be remembered that judge is also a human being

and they can make a mistake too. So, if we can take precautions steps when entered

into contracts by predicting all the consequences if there is a breach, it might be easy to

prove the evidences.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Arthur L. Corbin. (1944). The parol evidence Rule, 53. Yale Law Journal.

2. Bai Hira devi v Official Assignee, Bombay AIR 1958 SC 448

3. Blacks Law Dictionary. thelawdictionary.org.

4. Cheong, M. F. ( 2010). Contact Law in Malaysia. Sweet & Maxwell Asia

5. Coalfields of Burma Ltd v HH Johnson AIR 1925 Rang 128.

16

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

6. Dick Bentley Productions Ltd v Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd [1965] 2 All ER 65, 67

7. Emily M. Weitzenbeck. (2012). Norwegian Research Center for Computers &

Law. University of Oslo.

8. Foo Tock Lim v Piong Liew [1963] MLJ 67.

9. Heilbut Symons & Co v Buckleton [1913] AC 30.

10. Industrial Distribution Sdn Bhd v Golden Sands Construction Sdn Bhd [1993] 3

MLJ 433, HC.

11. J Evans & Sons v Andrea Merzario[1976] 2 All ER 930.

12. JJ Savage & Sons Pty ltd v Blakney (1970) 119 CLR 435 HC.

13. Kah Seng Construction Sdn Bhd v Selsin Development Sdn Bhd, [1997] 1 CLJ.

14. Kandasami v Mustafa [1983] 2 MLJ 85.

15. Kluang Wood products Sdn Bhd & Anor v Hong Leong Finance Berhad and Anor

[1991] 1 MLJ 193, FC.

16. Krishnan Arjunan and Abdul Majid Nabi Baksh. (2008). Contract Law in Malaysia.

Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd.

17. L Estrange v F Graucob Ltd[1934] 2 KB 394.

18. Ng Ee v PP [1941] MLJ 180.

19. Ng Kong Yue and Anor v R. [1962] MLJ 67.

20. Siah v Tengku Nong [1964] MLJ 63.

17

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

21. Syed Ahmad S A Alsagoff. (1998). Principles of the law of Contract in Malaysia.

(2nd ed.). Malayan Law Journal Sdn Bhd.

22. Tan Chong & Sons Motor Co Sdn Bhd v Alan Mcknight. [1979] 2 MLJ 229, FC.

23. Tan leng Teck v Sarjana Sdn Bhd & Ors [1997] 4 MLJ 239.

24. Tindok Besar Estate Sdn Bhd v Tinjar Co [1979] 2 MLJ 229.

25. Tyagaraja Mudaliar & Anor v Vadathanni [1936] MLJ 62.

26. United Malayan banking Corp. Bhd v Tan Lian Keng and Ors [1990] 1 MLJ 281

HC.

27. Visu Sinadhurai. (2003). Law of Contract. (3rd ed.). Butterworths (Canada)

Limited.

28. S. Santhana Dass. ( 2005). General principle of Contract Law in Malaysia.

Akitiara Corporation Sdn Bhd.

18

LXEB 1112 : Law of Contract

19

You might also like

- Parol Evidence RuleDocument2 pagesParol Evidence RuleMaisarah Shah100% (1)

- Parol Evidence Rule (PER)Document25 pagesParol Evidence Rule (PER)drismailmy83% (6)

- December 2018 (Law486 - Collateral Contract)Document2 pagesDecember 2018 (Law486 - Collateral Contract)Aisyah Johari100% (1)

- Notes Marriage 2 InsyirahDocument13 pagesNotes Marriage 2 InsyirahInsyirah Mohamad NohNo ratings yet

- Presentation Hearsay Evidence MalaysiaDocument9 pagesPresentation Hearsay Evidence MalaysiaN Farhana Abdul Halim0% (1)

- Collateral ContractsDocument5 pagesCollateral ContractsMuhamad Taufik Bin SufianNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Law of Torts in MalaysiaDocument23 pagesChapter 1: Law of Torts in MalaysiaSyed Azharul Asriq100% (1)

- Law of Evidence: Burden of Proof &standard of ProofDocument2 pagesLaw of Evidence: Burden of Proof &standard of ProofKhairun NisaazwaniNo ratings yet

- Course Outline-Law of Evidence IDocument72 pagesCourse Outline-Law of Evidence IIZZAH ZAHIN100% (1)

- Terms and RepresentationsDocument2 pagesTerms and Representationsmsyazwan100% (1)

- Implied TermsDocument3 pagesImplied TermsChamil JanithNo ratings yet

- NegligenceDocument36 pagesNegligenceeira87No ratings yet

- Distinction Between Nuisance and TrespassDocument10 pagesDistinction Between Nuisance and TrespassHarshita SarinNo ratings yet

- Confessions and AdmissionsDocument12 pagesConfessions and AdmissionsShi LuNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument5 pagesPrivity of ContractOwuraku Amoako-AttahNo ratings yet

- Modes of Civil ProceedingsDocument6 pagesModes of Civil ProceedingsMichelle ChewNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law 1 (Strict Liability)Document4 pagesCriminal Law 1 (Strict Liability)Mush EsaNo ratings yet

- 002 Acts F Bankruptcy NotesDocument26 pages002 Acts F Bankruptcy NotesSuzie Sandra SNo ratings yet

- The Civil Law Act MalaysiaDocument70 pagesThe Civil Law Act MalaysiaAngeline Tay Lee Yin100% (1)

- Aziz Bin Muhamad Din V Public ProsecutorDocument21 pagesAziz Bin Muhamad Din V Public ProsecutorFlorence Jefferson75% (4)

- 2.third Party ProceedingsDocument5 pages2.third Party ProceedingsAmanda F.No ratings yet

- Malaysia Criminal Procedure Code - ArrestDocument7 pagesMalaysia Criminal Procedure Code - ArrestKhairun NisaazwaniNo ratings yet

- Evidence of Similar Fact and ExceptionsDocument11 pagesEvidence of Similar Fact and ExceptionsConnieNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Code StudynoteDocument11 pagesCivil Procedure Code StudynoteSyafiq Affandy100% (5)

- Evi Chap 1Document26 pagesEvi Chap 1sherlynn100% (1)

- Parol Evidence Rule OutlineDocument32 pagesParol Evidence Rule OutlineJenna Alia100% (2)

- Implied Terms Stud - Version2Document40 pagesImplied Terms Stud - Version2Farouk Ahmad100% (1)

- Undertakings, EnforcementsDocument33 pagesUndertakings, EnforcementsZafry TahirNo ratings yet

- Tan ChongDocument3 pagesTan Chongnuhaya100% (1)

- Burden & Standard of ProofDocument6 pagesBurden & Standard of Proofdanish rasidNo ratings yet

- Alibi PDFDocument8 pagesAlibi PDFKen Lee100% (1)

- 2020 TOPIC 3 - Authority of Advocates Solicitors 11 MarchDocument24 pages2020 TOPIC 3 - Authority of Advocates Solicitors 11 Marchمحمد خيرالدينNo ratings yet

- Duty of CounselDocument24 pagesDuty of CounselKhairul Iman100% (3)

- Civil Procedure in Malaysian CourtDocument62 pagesCivil Procedure in Malaysian Courtmusbri mohamed94% (18)

- Strict Liability - Tort LawDocument19 pagesStrict Liability - Tort LawInsyirah Mohamad NohNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 RapeDocument36 pagesLecture 2 RapeMuhammad Najmi100% (1)

- Nullity of MarriageDocument34 pagesNullity of MarriageKhairul Idzwan100% (10)

- 4 Modes of Commencing Civil ProceedingsDocument13 pages4 Modes of Commencing Civil Proceedingsapi-3803117100% (1)

- 6 BailDocument19 pages6 Bailapi-380311750% (2)

- Chapter Two - Character EvidenceDocument12 pagesChapter Two - Character EvidenceNicholas NavaronNo ratings yet

- Public Prosecutor V Yuvaraj - (1969) 2 MLJ 8Document6 pagesPublic Prosecutor V Yuvaraj - (1969) 2 MLJ 8Eden YokNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 Law of Contract Subtopic 4Document30 pagesCHAPTER 2 Law of Contract Subtopic 4Fadhilah Abdul Ghani100% (1)

- Evidence TutoDocument15 pagesEvidence TutoFarahSuhailaNo ratings yet

- B Law - Assignment Answer GuideDocument2 pagesB Law - Assignment Answer GuideWai Shuen LukNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Mushrin Bin Esa 2011739935 (PLK 9) A) What Is The Grounds Upon Which The Bankruptcy Notice May Be Challenged?Document3 pagesMuhammad Mushrin Bin Esa 2011739935 (PLK 9) A) What Is The Grounds Upon Which The Bankruptcy Notice May Be Challenged?Mush EsaNo ratings yet

- Striking Out of Pleadings and Indorsements1Document90 pagesStriking Out of Pleadings and Indorsements1Nur Amirah SyahirahNo ratings yet

- Pre Trial Case ManagementDocument2 pagesPre Trial Case Managementnajiha lim100% (1)

- Contract Law 2Document199 pagesContract Law 2adrian marinacheNo ratings yet

- 1993 Constitutional CrisisDocument12 pages1993 Constitutional CrisisIrah Zinirah100% (2)

- Q8 Tutorial-Resulting TrustDocument2 pagesQ8 Tutorial-Resulting TrustNur ImanNo ratings yet

- Rangka Kursus Uuuk4083Document16 pagesRangka Kursus Uuuk4083Syaz SenoritasNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Islamic Legal SystemDocument43 pagesMalaysian Islamic Legal SystemSharifah HamizahNo ratings yet

- PrivilegeDocument3 pagesPrivilegeforensicmed100% (1)

- C7Document13 pagesC7EngHui EuNo ratings yet

- Estoppel in Equity: Discussion of Unification in Ireland Study NotesDocument6 pagesEstoppel in Equity: Discussion of Unification in Ireland Study NotesWalter McJasonNo ratings yet

- Offences Relating To Stolen PropertyDocument32 pagesOffences Relating To Stolen PropertyKhairul Iman92% (12)

- Advanced Criminal Procedure I - Assignment IDocument12 pagesAdvanced Criminal Procedure I - Assignment IKhairul Idzwan100% (1)

- Contract WorkDocument4 pagesContract Workbantu EricNo ratings yet

- Negotiation DocumentDocument5 pagesNegotiation Documentbhupendra barhatNo ratings yet

- ANS Per & CCDocument1 pageANS Per & CCputrideannaaNo ratings yet

- Declarations On Higher Education and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument2 pagesDeclarations On Higher Education and Sustainable DevelopmentNidia CaetanoNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Education Montessori Bauhaus andDocument10 pagesCosmic Education Montessori Bauhaus andEmma RicciNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Accounting PrinciplesDocument45 pagesChapter 11 Accounting PrinciplesElaine Dondoyano100% (1)

- Gwinnett Schools Calendar 2017-18Document1 pageGwinnett Schools Calendar 2017-18bernardepatchNo ratings yet

- PS2082 VleDocument82 pagesPS2082 Vlebillymambo0% (1)

- Procure To Pay (p2p) R12 - ErpSchoolsDocument20 pagesProcure To Pay (p2p) R12 - ErpSchoolsMadhusudhan Reddy VangaNo ratings yet

- Cw3 - Excel - 30Document4 pagesCw3 - Excel - 30VineeNo ratings yet

- BA 122.2 Accounts Receivable Audit Simulation Working Paper Group 6 WFWDocument5 pagesBA 122.2 Accounts Receivable Audit Simulation Working Paper Group 6 WFWjvNo ratings yet

- Icici History of Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI)Document4 pagesIcici History of Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI)Saadhana MuthuNo ratings yet

- Work Place CommitmentDocument24 pagesWork Place CommitmentAnzar MohamedNo ratings yet

- Gillette vs. EnergizerDocument5 pagesGillette vs. EnergizerAshish Singh RainuNo ratings yet

- Chinua Achebe: Dead Men's PathDocument2 pagesChinua Achebe: Dead Men's PathSalve PetilunaNo ratings yet

- Grile EnglezaDocument3 pagesGrile Englezakis10No ratings yet

- On Islamic Branding Brands As Good DeedsDocument17 pagesOn Islamic Branding Brands As Good Deedstried meNo ratings yet

- Mangalore Electricity Supply Company Limited: LT-4 IP Set InstallationsDocument15 pagesMangalore Electricity Supply Company Limited: LT-4 IP Set InstallationsSachin KumarNo ratings yet

- Human Resource ManagementDocument39 pagesHuman Resource ManagementKIPNGENO EMMANUEL100% (1)

- Ciplaqcil Qcil ProfileDocument8 pagesCiplaqcil Qcil ProfileJohn R. MungeNo ratings yet

- ECONOMÍA UNIT 5 NDocument6 pagesECONOMÍA UNIT 5 NANDREA SERRANO GARCÍANo ratings yet

- EA FRM HR 01 03 JobApplicationDocument6 pagesEA FRM HR 01 03 JobApplicationBatyNo ratings yet

- Oracle Fusion Global Human Resources Payroll Costing GuideDocument90 pagesOracle Fusion Global Human Resources Payroll Costing GuideoracleappshrmsNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology ReviewerDocument12 pagesGreek Mythology ReviewerSyra JasmineNo ratings yet

- Assignment F225summer 20-21Document6 pagesAssignment F225summer 20-21Ali BasheerNo ratings yet

- "The Old Soldier'S Return": Script Adapted FromDocument6 pages"The Old Soldier'S Return": Script Adapted FromMFHNo ratings yet

- City of Cleveland Shaker Square Housing ComplaintDocument99 pagesCity of Cleveland Shaker Square Housing ComplaintWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- CRPC MCQ StartDocument24 pagesCRPC MCQ StartkashishNo ratings yet

- Itinerary KigaliDocument2 pagesItinerary KigaliDaniel Kyeyune Muwanga100% (1)

- Form I-129F - BRANDON - NATALIADocument13 pagesForm I-129F - BRANDON - NATALIAFelipe AmorosoNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Economic GR - 2023 - The Extractive IndustriDocument11 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility and Economic GR - 2023 - The Extractive IndustriPeace NkhomaNo ratings yet

- National Budget Memorandum No. 129 Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesNational Budget Memorandum No. 129 Reaction PaperVhia ParajasNo ratings yet

- 3 Longman Academic Writing Series 4th Edition Answer KeyDocument21 pages3 Longman Academic Writing Series 4th Edition Answer KeyZheer KurdishNo ratings yet