Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bryson, Mary - Meno Lesbian - The Trouble With 'Troubling Lesbian Identities'

Uploaded by

usuariosdelserra1727Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bryson, Mary - Meno Lesbian - The Trouble With 'Troubling Lesbian Identities'

Uploaded by

usuariosdelserra1727Copyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [University of Toronto Libraries]

On: 14 November 2014, At: 13:07

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:

1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street,

London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of

Qualitative Studies in

Education

Publication details, including instructions for

authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tqse20

Me/no lesbian: The trouble

with 'troubling lesbian

identities'

Mary Bryson

Published online: 25 Nov 2010.

To cite this article: Mary Bryson (2002) Me/no lesbian: The trouble with 'troubling

lesbian identities', International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15:3,

373-380, DOI: 10.1080/09518390210122872

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09518390210122872

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all

the information (the Content) contained in the publications on our

platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors

make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy,

completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of

the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis.

The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be

independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and

Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings,

demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in

relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study

purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,

reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access

and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions

QUALITATIVE STUDIES IN EDUCATION, 2002, VOL. 15, NO. 3, 373 380

Essay review:

Me/no lesbian: the trouble with ``troubling lesbian

identities

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

MARY BRYSON

University of British Columbia

Subject to identity: Knowledge, sexuality, and academic practices in higher education.

By Susan Talburt (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000), 285 pp.,

$24.95, ISBN 0 7914 4572 0 (paper).

Meno. And how will you enquire, Socrates, into that which you do not know?

What will you put forth as the subject of enquiry? And if you nd what you

want, how will you ever know that this is the thing which you did not know?

(Plato, Meno)

As one civilized person to another: Matthew Shepard shouldnt have died. We

should all burn with shame. (Tony Kushner, author of Angels in America, from

The Nation, 11 November 1998)

It has taken me just over a year to write this review. The length of time this has taken

me is, in some signicant measure, related directly to the challenges of doing justice to

an intellectually substantial book that is, in my view, deeply problematic both politically and ethically. I have struggled with Susan Talburts exemplary ethnographic

study of three lesbian faculty members, not because of any specic intellectual or

technical limitations of her research but because of the tensions between its theoretical

commitments to postmodernism and what I construe as its practical and concomitant commitments

to political ambivalence. I have endeavored to read between Talburts sentences and to

ask what kind of story is Subject to identity, and in particular, what are its ethical

dimensions with respect to ending homophobi a and disrupting heteronormativit y

within the relentlessly heterosexist and homophobic hallways, playgrounds , sta rooms, and classrooms of North Americas public educational institutions. I begin

with an autobiographica l preamble as a way of locating myself as a particular kind

of reader of Talburts signicant, and, at times, brilliant text.

As a public and professional ``homosexual, I know what it is to experience

systemic discrimination. In my rst year (1989) as a faculty member at a major,

publicly funded Canadian university, I asked the Faculty Association to challenge

the institutions lack of access to spousal benets for gay and lesbian employees.

Overnight I was publicly identied as a ``lesbian, despite never having made that

claim myself, and was presumed and constructed as ``other and as ``deviant.

Overnight I went from ``young and promising new kid on the block to, in the

words of perhaps the most prominent feminist academic on campus, a ``political ass

who wouldnt get tenure anywhere in North America. I was marginalized in my

department, I got hate mail, students confronted me in classes and were sometimes

International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education ISSN 09518398 print/ISSN 13665898 online # 2002 Taylor & Francis Ltd

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/09518390210122872

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

374

mary bryson

downright hostile, and I got death threats on my answering machine. When I asked

my Dean to deal with the fact that homophobia was profoundly a ecting the quality

of my work environment, she angrily retorted by saying that since I couldnt prove it,

she was under no obligation to deal with it. After all, she said, there are other gay and

lesbian faculty who dont seem to experience any of these problems.

The ``dont ask dont tell policy was working well here. I was the only ``out

lesbian faculty member I was out on a limb and they were sawing it o . When my

tenure review rolled around, I began a year-long bloody battle for my professional life.

Twice I was formally denied tenure. Formal accounts written about my professional

accomplishments characterized my work as insubstantial and included disparaging

accusations about a lack of professionalism and unethical conduct on my part.

Resigned, I resigned. The university quickly accepted my resignation. My career as

an academic was, e ectively, over. I wrote an impassioned letter to the university

president outlining the errors, omissions, and just plain lies that littered my tenure le.

A month later, I received a phone call from the presidents o ce asking me to please

pick up the letter containing his recommendation. A few weeks after delivering what I

had thought then was my nal lecture a paper (Bryson & de Castell, 1993) about

how being a lesbian in a faculty of education constituted , to paraphrase Nicole

Brossard, an unten(ur)able discursive posture, I was awarded tenure.

A decade later, the same university approved an undergraduat e minor in ``Lesbian

and Gay Studies. The steering committee, made up of queer faculty, which I had

founded to consider curricular issues following the spousal benets victory, met at the

last minute to discuss a proposed program name change to ``Critical Studies in

Sexuality. The discussions that took place around the name change were highly

charged, emotionally explosive, and tense. An odd bifurcation emerged in the arguments of the group in favor of the name change. Intellectually sophisticate d expositions of postmodern ``identity as performance and ``identity as discourse, which I

want to argue are actually anti-identity theories, were juxtapose d with seemingly

pragmatic concerns that potential donors to this program as well as prospective

students might be put o by a necessary association with the words ``Lesbian and

``Gay. In a moment that, several years later, still makes me nauseous, I found myself

locked in a losing battle where the most sophisticated theoretical constructs of the day

were being used to shore up what looked to me like a homophobic and discriminatory

name change a change that put ``lesbian and ``gay back in the closet, cloaked in

shame, ridiculed as ``essentialist and ``old school and disposable, because identity

politics was bad for business. ``Lesbian and Gay never for a minute did I somehow

fail to understand the intellectual signicance of theoretical anti-essentialist arguments

against a simple representationalis t ontology. Rather, it seemed that if simply being

identied ``as one could still, like Matthew Shepard, get you killed, then institutionalized ambivalence about laying claim to this label was a choice with ethical consequences that I simply could not accept.

Emancipatory ideals have been a critical part of the liberal social justice project of

public education in North America for more than a century. A late arrival on the

institutional antidiscrimination agenda has been homophobia, and the implementation

of proactive equity policies to address the specic needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgendere d (LGBT) members of educational institutions. At school (as elsewhere),

few LGBT persons, whether teachers or students, nd themselves in environments

where it is either safe, or considered appropriate, to identify publicly as such

(Khayatt, 1994; Smith & Smith, 1998). And publicly funded schools, whether ele-

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

me/no lesbian

375

mentary or postsecondary , have dragged their feet and given voice to a signicant

chorus of nay-sayers dead set against addressing the equity needs of LGBT community

members, let alone undertaking as a serious intellectual project the goal of considering

the epistemological, curricular, and pedagogical consequences of the systemic exclusion of LGBT topics, themes, and contributions from the canon.

Subject to identity: Knowledge, sexuality, and academic practices in higher education by Susan

Talburt engages the reader critically with the di erence being a lesbian faculty member might make to business-as-usua l at Liberal U, described as a North American

research university. Reciprocally, this research also tackles the ways in which, as a

signicant ``modier, academic might distinctively inect the meanings of lesbian when

juxtaposed in the realm of higher education. Talburts research consists of ethnographic case studies of three women: Olivia, a white associate professor of English;

Julie, a white full professor of religious studies; and Carol, an African-American

assistant professor of journalism. And there is more to this project than a carefully

crafted ethnographic account of academic culture and the lives of three lesbian faculty

members.

Subject to identity does a lot of its best work on the theoretical plane, engaging with

great scholarly rigor (a) contemporary debates about the increasingly corporate state

of higher education as read through the lens of the late Bill Readingss (1996) The

university in ruins; (b) performative models of identity, agency, and di erence that

challenge the monologic character of identity politics and enrich and expand protably on de Certeaus (1984) Practice of everyday life; and (c) complex and shifting

relationships between alterity and pedagogical authority by means of ne-grained

eldwork that exposes what Talburt refers to as the ``local renegotiations of the social

and academic in the professional lives of Carol, Olivia, and Julie (p. 74).

As a way of getting into Talburts story about lesbian academics, lets start by

taking a close look at the teller of this tale, how Talburt constitutes her authorial

identity vis-a-vis her subject(s), and, equally as crucial, to consider the signicance of

the make-up of her research sample who are her main characters, and just what kind

of lesbian academics are they? Threaded through both Talburts own identity-disclosure statements and her description of the three women chosen for this project is an

overarching ambivalence concerning the signicance of being lesbian to ones various

engagements with/in higher education. In the introduction to the book, Talburt

distances herself from the subject/s of her inquiry, referring to lesbians as ``they,

and makes the following enigmatic claim: ``I began with lesbian at the center of my

inquiry. To invoke the category locates me, I suspect, as a person who has beneted

from participation in social, political and intellectual projects undertaken by lesbians,

despite my ambivalences (p. 4).

Since, up to this point in the text, lesbians have been invoked as a category of

persons who actually exist in the world (as opposed to a convenient discursive ction),

and have been Othered pronominally by being referred to as they (e.g., ``Implicit in

my thinking were beliefs that there may be something `di erent in the work of

lesbian-identied academics, that their `voices are not canonized, and that they may

have identiably di erent relations to students or knowledges because they are lesbian

[emphasis added] (p. 3), the reader is left not knowing what, other than a kind of

detached scholarly interest, would motivate an apparently nonlesbian academic to, as

Talburt puts it, ``disturb habits of thinking about the points of intersection of lesbian

and academic (p. 1). This research asks, ``What if `lesbian isnt a salient lens? Or a

personal identity? (p. 23). Talburt asks, pointedly, ``What does it mean to conduct

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

376

mary bryson

an empirical study of lesbian academics if lesbian does not carry stable meanings? (p.

14).

Much like the Socratic conundrum that philosophers refer to as ``Menos

Paradox or the ``Paradox of Inquiry (Cohen, 2000), an important question for

researchers, and one that is raised by Subject to identity, is: How can you inquire into

something about which you know nothing that is empirically veriable, objective, or

nite? This is also a paradigmati c puzzle for researchers working ``with/in the postmodern (Lather, 1991).

In Platos (1953) Meno dialogue, Socrates shows Meno through an elaborate, and,

Higgins (1994) argues, arrogant and arbitrary language game, that nothing Meno

thought he knew about virtue (arete) holds. Truth dissolves into language, or discourse,

we might say, today (see Butler, 1997; Derrida, 1978; and for incisive critiques see also

Brodribb, 1992; Smith, 1999).

Critical motivational and concomitant ethical and political questions must be

asked concerning the destabilizing inquirer role played by Socrates in the Meno, and

Talburt in Subject to identity. It is commonly assumed that relentless inquiry is motivated by a desire for knowledge and insight, and that its purported educative e ects

are either benign, or positive. However, as Jackson (2001) notes, ``After all his

attempts at dening `arete have been dismissed, an exasperated Meno claims that

Socrates interrogation has `stunned him as would the shock of the torpedo sh. The

e ect of the interrogation has not illuminated Menos knowledge of what `arete is but

robbed him of that knowledge.

A persistent question that haunted my reading of Subject to identity was: What are

the ethical implications of conducting research that aims to destabilize lesbian identity?

What does it mean to carry out a deconstructive ontological project within a realm

that looks, to me, like a battleeld littered with wounded bodies and peopled with

proud men and women who have put their lives, careers, family a liations and the

like on the line just for the right to lay claim, and proudly, to lesbian or gay identity?

As Braidotti (1987) argues: ``In order to announce the death of the subject, one must

rst have gained the right to speak as one.

If Talburts research focus is lesbian academics, why choose Julie, Olivia, and Carol

as case-study subjects? What salient characteristics inect and skew this tiny sample?

Well, it is probably of greatest salience to this reader that, like Talburt, all three

women are, paradoxically, given the projects ostensive goal, deeply ambivalent

about being lesbians. As Talburt notes, ``Lesbian identity was not central to the

womens understanding of self or the constitution of their department positionings

(p. 139). She a rms, in even more unambiguous terms, that, ``Julie, Olivia, and Carol

do not seek agency through voice and visibility as lesbians but in the domain of their

intellectual lives (p. 220)

In fact, Talburts interviews, and eldnotes from classroom observations , indicate

that all three have intentionally shaped their pedagogical and other professional

practices in relation to the topic of (homo)sexualit y so as to assure for themselves

classroom and departmental spaces of nondisclosure and nonidentication as ``lesbian. As Julie puts it, ``All it [self-disclosure as a lesbian] would do to those poor

little freshmen sitting in my Introduction to Christianity class would just make them

all upset (p. 103). Olivia is described as ``an academic `star whose intellectual

project is to debunk the category lesbian . . . ` (p. 27). Drawing on an interview

with Olivia, Talburt reports on ``her rejection of self-announcing her sexual orientation, and her dissatisfaction with lesbian communities and political activism (p. 28).

me/no lesbian

377

Carol, Talburt writes, ``denes her roles as faculty member . . . primarily in relation to

her race and gender . . . . Her race obscures her lesbianism . . . (p. 29). On the topic

of self-disclosure, Carol argues:

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

I dont have to reveal my sexuality to teach about it any more than a straight

person. . . . I want my sexuality to be ambiguous. . . . Even better if they think I

am a straight black woman who raises the subject because it is crucial to our

understanding of whatever were talking about. (p. 96)

And I must add, here, that Talburts description of Carol, gleaned from her eldnotes

written just after their rst meeting, seems bizarre, redolent with practices of stigmatization, and racist, despite the authors weak rhetorical strategy of distancing herself

from the account by framing it as ``imagining colleagues responses to her: ``She

strikes me as an `acceptable black. She is well-spoken, articulate, uses `standard

English and doesnt slip into jargon or threatening dialects. . . . Shes not scary in

appearance, either as black or as lesbian autonomou s body movement but not

dykey (p. 31).

One of the strengths of Talburts research as it is reported in Subject to identity

consists in its careful attention via extensive microgenetic eldwork, including multiple in-depth interviews and classroom observations, to the ways in which particular

actions undertaken by Carol, Olivia, and Julie are both constitutive of their identities

in practice, and constituted by what Dorothy Smith (1999) refers to as the ``ruling

relations that give shape to power as it operates in institutional contexts. Talburt

describes this as ``Julies, Olivias, and Carols enactments of intellectual in academic

practice (p. 67) and as ``the construction of Olivias, Carols, and Julies pedagogical

uses of existing norms relating to knowledge and identity as articulations of their

intellectual lives, yet mediated by institutional and social structures (p. 74)

The most trenchant questions I am left with after my multiple readings of Subject to

identity are as follows. First, what is the role of data collection when the research sample

so clearly is skewed in the direction of creating apparently authoritativ e empirical

support for Talburts theoretical bent that ``lesbian isnt a salient lens? How might

Talburts story have changed had she included in her sample (a) successful lesbian

academics who, unlike Carol, Julie, and Olivia, are unabashedly ``queer, out, and

proud in their various roles as university-base d intellectuals; (b) lesbian academics

whose careers have been threaded through with institutionally and personally

mediated gay-bashing ; and (c) women who have been red from their academic

jobs because of homophobi c responses to their determination to be unambiguousl y

and publicly ``lesbian? And by this, I most emphatically do not mean academics who

are partial to a simple, identity politics notion of ``lesbian as constitutive of some kind

of unproblematic ontological category.

In a discussion of the complexities involved in teaching a lesbian studies course

with Suzanne de Castell (Bryson & de Castell, 1993), we argued that the tensions

between postmodern challenges to identity politics and the material struggles of

people identied as gay or lesbian constitute a starting-point for inquiry, and not

an argument for dispensing with identity, as follows:

Invariably, speaking as a lesbian, one is the discursive outsider rmly

entrenched in a marginal essentialized identity that, ironically, we have to

participate in by naming our di erence this is rather like having to dig

ones own ontological grave . . . . Reading the Concise Oxford English Dictionary

378

mary bryson

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

one dis/covers:

Queer: verb- to spoil, put out of order, to put into an embarrassing or disadvantageous

situation.

It seems that a worthwhile avenue for the elucidation of a queer praxis might be

explored here by considering the value of an actively que(e)rying pedagogy of

queering its technics and scribbling gra ti over its texts, of coloring outside of

the lines so as to deliberately take the wrong route on the way to school going

in an altogether di erent direction than that specied by a monologic destination. This seems a promising approach indeed for refashioning pedagogy in the

face of the myriad institutionall y sanctioned ``diversity management

(Mohanty, 1990) programs that, today, threaten to crowd out and silence

most opportunities for radical emancipatory praxis.

Second, what benets are likely accrued, and for whom, from making ones lesbianism ambiguous and a site of performed ambivalence? A fundamental question not

addressed in Talburts work is whether it is the same thing to be ambivalent about

lesbianism as it is about heterosexuality . Or to put it another way: is ambivalence

about ones heterosexual identity simply the status quo (which has its own politics)

and self-admitted and self-conscious ambivalence about ones lesbian identity a form

of political quietism?

One might reasonably conclude that Talburt enlisted the voices of these three

women in particular so as to recount, and lend authority to, a very specic kind of

tale about how to be a successful lesbian academic a ``good lesbian whose ambivalent performance of her lesbianism ensures continuity for the predominantly heterosexist discursive economy of Liberal U. As Talburt notes, Liberal U is not a safe haven

for gays and lesbians: ``While some undergraduat e and graduate students are `out on

campus, few gay and lesbian faculty are open about their sexuality (p. 52). And

Talburt explains further that the active construction of silences concerning homosexuality, otherwise referred to as ``Dont ask, dont tell, is connected to tacit expectations

of who faculty are and what they do, playing itself out in denitions of acceptable or

unacceptable behavior (p. 70). And so, it seems to this reader, unacceptabl e that a

very important question raised in Subject to identity remains fundamentally unexamined

and unanswered, concerning the validity of Talburts argument that ``Ambiguity as

well can combat heterosexism and homophobia (p. 96).

My third and nal question is related to the rst two, and gestures both to the

di culties, and the ethical implications for researchers of, as Talburt puts it, ``invoking a category whose meanings at once seem overdetermined and at other moments

elusive (p. 34). Talburt concludes, ``By centering much of my inquiry on intellectual,

personal, and professional meanings of `lesbian . . . I have invoked a category that can

obscure more than it reveals (p. 191). I disagree vehemently with this conclusion and

want to suggest, in its place, that it is only by conducting research that initially sought

out a totalizing answer to the question ``What/Who is a lesbian academic? that one

could then conclude that an invocation of the category produces obscurity and overdetermined meanings.

In essence, what seems most productive about Subject to identity is that, by means of

elegantly executed eldwork, Talburt has produced a compelling portrait of the

practices that both constitute, and are constituted by, successful female academics

who are ambivalent about taking up lesbian identity in their professional culture. A

conclusion inspired by Go mans (1963) work on the ``identity management strate-

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

me/no lesbian

379

gies of the stigmatized might be to say that successful lesbian academics work diligently and intentionally to reduce the impact of homophobia. To put forward ``lesbian as an ontological category a category of being whose meaning(s) are

amenable to elucidation and explication by means of empirical research methods,

and are then systematically destabilized by deconstructive inquiry, is, like Socrates

in the Meno, to be implicated in a ``language game inevitably doomed to produce

aporia the limits of what can be known, and doubt concerning what once seemed like

commonsensical constructs.

We dont and cant know what ``lesbian means, where lesbian refers to an ontological

category that is always already overdetermined by culturally and historically specic

discursive formations. We do, however, know about the practices of the ideology of

homophobi a including its insistence on lesbian silence and ambivalence and therefore we have to pay very close critical attention to any project that prioritizes and

appears to give value to normativizes ambivalence about lesbian identity, especially as it really does nothing to deal with what we do know about, which is systemic

discrimination against those identied as lesbian or gay. As Monique Wittig (1995,

personal communication) argued during a discussion about the ethical implications of

postmodernism(s ) for lesbian and gay studies: ``The real question about lesbians is not,

`Who are we?, but, `How have we survived?.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Hart Caplan for his insightful comments on emergent drafts.

Note

1. Subject to identity is based on Talburts (1996) dissertation research, entitled, Troubling lesbian identities:

intellectual voice and visibility in academia.

References

Braidotti R. (1987). Envy: or, With my brains and your looks. In A. Jardine & P. Smith (Eds.), Men in

feminism (pp. 233241). New York: Routledge, Chapman, & Hall.

Brodribb, S. (1992). Nothing mat(t)ers: A feminist critique of postmodernism. Toronto, CA: James Lorimer.

Butler, J. (1997). The psychic life of power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bryson, M., & de Castell, S. (1993a) . Lesbian/Lecturer: An ``untenable discursive posture? Paper presented at a

meeting of Queer Sites, Toronto, Canada.

Bryson, M., & de Castell, S. (1993b). Queer pedagogy: Praxis makes im/perfect. Canadian Journal of

Education, 18(2), 285305. [Available: http://www.educ.ubc.ca/faculty/bryson/gentech/queer.html]

Cohen, S. (2001). Menos paradox. Unpublished paper. Available: [http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/

320/menopar.htm]

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

de Castell, S., & Bryson, M. (1997). ``Dont ask, dont tell: Sexualities and their treatment in educational

research. In W. Pinar (Ed.), Curriculum: Toward new identities for the eld. New York: Garland Press.

[Available: http://www.educ.ubc.ca/faculty/bryson/gentech/pinar.html]

Derrida, J. (1978). Writing and di erence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Go man, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cli s, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Higgins, C. (1994). Socrates e ect/Menos a ect: Socratic elenchus as kathartic therapy. Paper presented at an

annual meeting of the Philosophy of Education Society (PES).

Jackson, E. (2001). Meno: Reading one. Unpublished paper. [Available: http://www.anotherscene.com/meaning/ejmeno1.html]

380

me/no lesbian

Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 13:07 14 November 2014

Khayatt, D. (1994). Surviving school as lesbian students. Gender and Education, 6(1), 4761.

Lather, P. (1991). Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern. New York: Routledge.

Plato (320 bc/1953). The dialogues of Plato (trans. B. Jowett). Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Available: http://

classics.mit.edu/Plato/meno.html]

Readings, W. (1996). The university in ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, D. (1999). Writing the social. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, G., & Smith, D. (1998). The ideology of ``fag: The school experience of gay students. Sociological

Quarterly, 39(2), 309336.

Talburt, S. (1996). Troubling lesbian identities: Intellectual voice and visibility in academia. PhD Thesis, Vanderbilt

University, DAI Vol. 57-11A.

You might also like

- Bonnie Thorton Dill, Ruth Enid Zambrana, Patricia Hill Collins-Emerging Intersections - Race, Class, and Gender in Theory, Policy, and Practice (2009)Document327 pagesBonnie Thorton Dill, Ruth Enid Zambrana, Patricia Hill Collins-Emerging Intersections - Race, Class, and Gender in Theory, Policy, and Practice (2009)Andrea TorricellaNo ratings yet

- Mystery LearnersDocument12 pagesMystery Learnersapi-450801939No ratings yet

- Argumentative EssayDocument6 pagesArgumentative Essayapi-28603785175% (4)

- Transgender History (Seal Studies) - Susan Stryker PDFDocument243 pagesTransgender History (Seal Studies) - Susan Stryker PDFOrfeu Jazz85% (13)

- 9781000606997Document219 pages9781000606997Morgan SullivanNo ratings yet

- Racial Discrimination against Black Teachers and Black Professionals in the Pittsburgh Publice School System: 1934-1973From EverandRacial Discrimination against Black Teachers and Black Professionals in the Pittsburgh Publice School System: 1934-1973No ratings yet

- Is There More To Freedom Than Absence of External Constraints?Document3 pagesIs There More To Freedom Than Absence of External Constraints?Marceli PotockiNo ratings yet

- Barker - Foucault - An IntroductionDocument186 pagesBarker - Foucault - An IntroductionNeal PattersonNo ratings yet

- Alice Hom - Lesbia of Color Community BuildingDocument298 pagesAlice Hom - Lesbia of Color Community BuildingFausto Gómez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Be Professional! : //server05/productn/H/HLG/33-1/HLG104.txt Unknown Seq: 1 27-JAN-10 11:45Document14 pagesBe Professional! : //server05/productn/H/HLG/33-1/HLG104.txt Unknown Seq: 1 27-JAN-10 11:45Anne AlencarNo ratings yet

- My University Sacrificed Ideas For Ideology. So Today I Quit. - by Peter Boghossian - Common Sense With Bari WeissDocument7 pagesMy University Sacrificed Ideas For Ideology. So Today I Quit. - by Peter Boghossian - Common Sense With Bari WeissAngel MercadoNo ratings yet

- Compare Essays For PlagiarismDocument7 pagesCompare Essays For Plagiarismdnrlbgnbf100% (2)

- A Pedagogical Imperative of Pedagogical Imperatives. Lewis Gordon.Document10 pagesA Pedagogical Imperative of Pedagogical Imperatives. Lewis Gordon.Víctor Jiménez-BenítezNo ratings yet

- Transgender Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesTransgender Research Paper Topicsafnkceovfqcvwp100% (1)

- From Single to Serious: Relationships, Gender, and Sexuality on American Evangelical CampusesFrom EverandFrom Single to Serious: Relationships, Gender, and Sexuality on American Evangelical CampusesNo ratings yet

- Newcombe Doctoral Dissertation FellowshipDocument4 pagesNewcombe Doctoral Dissertation FellowshipPaperWritingHelpOnlineCanada100% (1)

- Literature Review TransgenderDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Transgenderc5kby94s100% (1)

- Kimberlé Crenshaw On Intersectionality, More Than Two Decades Later Columbia Law SchoolDocument2 pagesKimberlé Crenshaw On Intersectionality, More Than Two Decades Later Columbia Law SchoolBrianna ReyesNo ratings yet

- A Lesbigay Guide to Selecting the Best-Fit College or University and Enjoying the College YearsFrom EverandA Lesbigay Guide to Selecting the Best-Fit College or University and Enjoying the College YearsNo ratings yet

- Risby - Scholarly ReflectionDocument10 pagesRisby - Scholarly Reflectionapi-599588127No ratings yet

- Rights and Responsibilities in Rural South Africa: Gender, Personhood, and the Crisis of MeaningFrom EverandRights and Responsibilities in Rural South Africa: Gender, Personhood, and the Crisis of MeaningNo ratings yet

- On Political Correctness - William DeresiewiczDocument8 pagesOn Political Correctness - William Deresiewiczbillludley_15No ratings yet

- Feminist Technical Communication: Apparent Feminisms, Slow Crisis, and the Deepwater Horizon DisasterFrom EverandFeminist Technical Communication: Apparent Feminisms, Slow Crisis, and the Deepwater Horizon DisasterNo ratings yet

- Moving Beyond The Inclusion of Lgbt-Themed Literature in EnglishDocument11 pagesMoving Beyond The Inclusion of Lgbt-Themed Literature in Englishapi-253946120No ratings yet

- "That's So Gay!" - A Study of The Deployment of Signifiers of Sexual and Gender Identity in Secondary School Settings in Australia and The United StatesDocument21 pages"That's So Gay!" - A Study of The Deployment of Signifiers of Sexual and Gender Identity in Secondary School Settings in Australia and The United Stateskangqi zhouNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Women Gender Sexuality StudiesDocument133 pagesIntroduction To Women Gender Sexuality StudiesM.IMRANNo ratings yet

- In Response To Academic Freedom and Free SpeechDocument3 pagesIn Response To Academic Freedom and Free SpeechPeter HassonNo ratings yet

- Enc1102 Fall22 Annotated Bibliography 4Document11 pagesEnc1102 Fall22 Annotated Bibliography 4api-644652870No ratings yet

- Did We Forget?Document2 pagesDid We Forget?thedukechronicleNo ratings yet

- Power and Positionality - Negotiating Insider:Outsider Status Within and Across CulturesDocument14 pagesPower and Positionality - Negotiating Insider:Outsider Status Within and Across CultureshedgerowNo ratings yet

- LGBTQ CultureDocument8 pagesLGBTQ Cultureapi-308583630No ratings yet

- MITSP 406F10 TransgenderDocument19 pagesMITSP 406F10 TransgenderTedi TrikoniNo ratings yet

- Activist Literacies: Transnational Feminisms and Social Media RhetoricsFrom EverandActivist Literacies: Transnational Feminisms and Social Media RhetoricsNo ratings yet

- In The Name of Morality. Moral Responsibility, Whiteness and Social Justice Education.2005Document15 pagesIn The Name of Morality. Moral Responsibility, Whiteness and Social Justice Education.2005Sarah DeNo ratings yet

- Carol B. Stack Etnografia e Prática FeministaDocument14 pagesCarol B. Stack Etnografia e Prática FeministaJuliane Oliveira NunesNo ratings yet

- Getting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesDocument24 pagesGetting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesKender ZonNo ratings yet

- Just What Is Critical Race Theory and Whats It Doing in A Nice Field Like EducationDocument19 pagesJust What Is Critical Race Theory and Whats It Doing in A Nice Field Like EducationJulio MoreiraNo ratings yet

- LGBT Bullying in School: Perspectives On Prevention: Communication Education October 2018Document32 pagesLGBT Bullying in School: Perspectives On Prevention: Communication Education October 2018gabriela marmolejoNo ratings yet

- Social Justice LetterDocument3 pagesSocial Justice Letterapi-640451371No ratings yet

- Decolonizing Transgender: A Roundtable DiscussionDocument21 pagesDecolonizing Transgender: A Roundtable DiscussionMartin De Mauro RucovskyNo ratings yet

- FWD A Message About The Media Coverage in The Recent DaysDocument3 pagesFWD A Message About The Media Coverage in The Recent DaysWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- Henry Giroux On Democracy UnsettledDocument12 pagesHenry Giroux On Democracy UnsettledKimNo ratings yet

- A Response To Erica BurmanDocument9 pagesA Response To Erica BurmanplinaophiNo ratings yet

- Racism Today Term PapersDocument5 pagesRacism Today Term Papersdhryaevkg100% (1)

- On Teacher Neutrality: Politics, Praxis, and PerformativityFrom EverandOn Teacher Neutrality: Politics, Praxis, and PerformativityDaniel P. RichardsNo ratings yet

- Consent On Campus A Manifesto Donna Freitas Full ChapterDocument67 pagesConsent On Campus A Manifesto Donna Freitas Full Chapterroger.betschart467100% (6)

- This Content Downloaded From 173.199.117.44 On Thu, 09 Sep 2021 19:41:01 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 173.199.117.44 On Thu, 09 Sep 2021 19:41:01 UTCVanessa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher EducationFrom EverandConsider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher EducationNo ratings yet

- The Sex Lives of College Students: Three Decades of Attitudes and BehaviorsFrom EverandThe Sex Lives of College Students: Three Decades of Attitudes and BehaviorsNo ratings yet

- This Was My Hell The Violence Experienced by Gender Non Conforming Youth in US High SchoolsDocument23 pagesThis Was My Hell The Violence Experienced by Gender Non Conforming Youth in US High Schoolsk5b6pwbwq4No ratings yet

- Immersion Paper Fall 2014Document10 pagesImmersion Paper Fall 2014api-315607531No ratings yet

- Term Paper About TransgenderDocument7 pagesTerm Paper About Transgenderafdtsxuep100% (1)

- Kowalski Dilks Wade Book Review PUBLISHEDDocument3 pagesKowalski Dilks Wade Book Review PUBLISHEDMD SIAMNo ratings yet

- Racism in Schools Research PaperDocument5 pagesRacism in Schools Research Paperozbvtcvkg100% (1)

- The Ideology of "Fag"Document10 pagesThe Ideology of "Fag"PersonmanNo ratings yet

- Why It's Worth Listening To People You Disagree WithDocument2 pagesWhy It's Worth Listening To People You Disagree WithNg Lê Huyền AnhNo ratings yet

- Polyamorous IdentityDocument19 pagesPolyamorous IdentityHermès-Louis RolandNo ratings yet

- Meghan Murphy ?gender Identi Ty and Women's Rights,"Document7 pagesMeghan Murphy ?gender Identi Ty and Women's Rights,"Chiara100% (1)

- Alice Dreger - Can We Have Sex BackDocument5 pagesAlice Dreger - Can We Have Sex BackdpolsekNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument4 pagesAnnotated BibliographyLito Michael MoroñaNo ratings yet

- To (O) Queer or Not?: Journal of Lesbian StudiesDocument11 pagesTo (O) Queer or Not?: Journal of Lesbian StudiesMila ApellidoNo ratings yet

- N Tylistics: A B L T, C P by José Ángel G L (University of Zaragoza, Spain)Document11 pagesN Tylistics: A B L T, C P by José Ángel G L (University of Zaragoza, Spain)usuariosdelserra1727No ratings yet

- History of Female BreastDocument303 pagesHistory of Female Breastusuariosdelserra172750% (2)

- Trans - Exclusionary Radical Feminists (Terfs) Are Engaged in A Political Project ToDocument9 pagesTrans - Exclusionary Radical Feminists (Terfs) Are Engaged in A Political Project Tousuariosdelserra1727No ratings yet

- The EmergenceDocument20 pagesThe Emergenceusuariosdelserra1727No ratings yet

- A Plea For Ordinary Sexuality: EditorialDocument2 pagesA Plea For Ordinary Sexuality: Editorialusuariosdelserra1727No ratings yet

- 2001, 8, 1Document95 pages2001, 8, 1usuariosdelserra1727No ratings yet

- The Silence - Barriers and Facilitators To Inclusion of Lesbian Gay and Bisexual Pupils in Scottish SchoolsDocument241 pagesThe Silence - Barriers and Facilitators To Inclusion of Lesbian Gay and Bisexual Pupils in Scottish Schoolsusuariosdelserra1727100% (1)

- Discursive Analytical Strategie - Andersen, Niels AkerstromDocument157 pagesDiscursive Analytical Strategie - Andersen, Niels Akerstromi_pistikNo ratings yet

- Auditory PerceptionDocument9 pagesAuditory PerceptionFrancis Raymundo TabernillaNo ratings yet

- EAPP MediaDocument2 pagesEAPP MediaJaemsNo ratings yet

- Jim Dine Tool RubricDocument1 pageJim Dine Tool Rubricapi-375325190No ratings yet

- Ips Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesIps Lesson Planapi-531811515No ratings yet

- 15 Spiritual GiftsDocument62 pages15 Spiritual Giftsrichard5049No ratings yet

- 17 "Flow" Triggers That Will Increase Productivity - Tapping Into Peak Human Performance in BusinessDocument7 pages17 "Flow" Triggers That Will Increase Productivity - Tapping Into Peak Human Performance in BusinessFilipe RovarottoNo ratings yet

- Cools, Schotte & McNally, 1992Document4 pagesCools, Schotte & McNally, 1992Ana Sofia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- C4 - Learning Theories and Program DesignDocument43 pagesC4 - Learning Theories and Program DesignNeach GaoilNo ratings yet

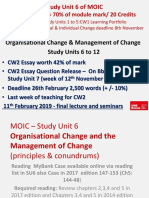

- MOIC L6 - Final 2018-19 - Change Conundrum & Managing Change - Student VersionDocument34 pagesMOIC L6 - Final 2018-19 - Change Conundrum & Managing Change - Student VersionAnonymous yTP8IuKaNo ratings yet

- Management AccountingDocument9 pagesManagement Accountingnikhil yadavNo ratings yet

- A Text Book of Psychology and Abnormal PsychologyDocument237 pagesA Text Book of Psychology and Abnormal PsychologyPaul100% (1)

- PRDocument5 pagesPRJhon Keneth NamiasNo ratings yet

- Essay Marking Criteria and SamplersDocument8 pagesEssay Marking Criteria and SamplersMuhammad AkramNo ratings yet

- Support File For Elcc Standard 6Document1 pageSupport File For Elcc Standard 6api-277190928No ratings yet

- James Allen - As A Man Thinks PDFDocument28 pagesJames Allen - As A Man Thinks PDFalinatorusNo ratings yet

- Teaching Science Using Inquiry ApproachDocument14 pagesTeaching Science Using Inquiry ApproachAtarah Elisha Indico-SeñirNo ratings yet

- Learning Implementation PlanDocument9 pagesLearning Implementation PlanMadya Ramadhani11No ratings yet

- Narrtive Essay 1Document5 pagesNarrtive Essay 1api-301991074No ratings yet

- Architectural Thesis Outline and Review Dates Revised VersionDocument3 pagesArchitectural Thesis Outline and Review Dates Revised Versionindrajitdutta3789No ratings yet

- The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins GilmanDocument8 pagesThe Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins GilmanJYH53No ratings yet

- Topic 05 All Possible QuestionsDocument9 pagesTopic 05 All Possible QuestionsMaxamed Cabdi KariimNo ratings yet

- CPA ApproachDocument17 pagesCPA ApproachARMY BLINKNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesLesson Planapi-220704318No ratings yet

- Tapescript of Pas Bsi Xii Sem 1 2022Document6 pagesTapescript of Pas Bsi Xii Sem 1 2022Ari PriyantoNo ratings yet

- 1984 - J - The Behaviorism at FiftyDocument54 pages1984 - J - The Behaviorism at Fiftycher themusicNo ratings yet

- A Short History of Performance ManagementDocument17 pagesA Short History of Performance ManagementTesfaye KebedeNo ratings yet