Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Race and Theology in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

Uploaded by

Cydonia714Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Race and Theology in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

Uploaded by

Cydonia714Copyright:

Available Formats

Cisristimlity and Litemture

Vol. 59, No.2 (Winter 20/0)

Fraught with Fire:

Race and Theology in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

Lisa M. Siefker Bai ley

Written in the form of a spiraling letter with qualities of a sermon, a

meditation, a diary. and a journal, Marilynne Robinson's Gilead offers a

reflection of both lamentation and celebration but ends with a hope for a

restoration Robinson presents as transcendence. Due to his terminal heart

condition, the letter's author, Congregationalist minister John Ames. knows

he will not spend much time with his son on earth. Ames laments this fact

through words he hopes will allow him to connect in deep meaningful ways

with the grown son he is destined not to know in Ihis life. Ames writes this

letter with the sa me zeal he wrote sermons in his career, sermons which

willialer be burned. As Ames faces the mystery of death, he becomes ever

closer to God, both spiritually and literally. For Christians like Ames. there's

life after death. Here on earth, there is something good in the mystery of

what he doesn't understand. Robinson suggests a transcendent notion of

Christianity that encompasses both larger mysteries. One way Robinson

represents these mysteries is through the shifting and contrary symbol of

fi re. The novel is so rich with images of fire that Elle book reviewer Lisa

Shea calls Gilead "laJn inspired work from a writer whose sensibility seems

steeped in holy fire" (J 70). Ames' story uses fire as a representation of the

energy ofheing, which can become destructive like the puritanical mistakes

made in Ames' grandfather's church. or transcendent. like the filling of the

Holy Spiri!. 1

We have seen Robinson use images of water, air, earth, and fi re in

HOllsekeeping. Stefan Mattessich has suggested that fire in HOllsekeeping

provides a Derridean metaphor of spirit (75). Mattessich points out that

Sylvie's bonfire which burns her collection of magazines and newspapers

becomes a kind of "fire-writing" that helps to draw boundaries around

social norms in communication (75-76). "What goes up in flames for Ruth

and Sylvie:' writes Mattessich, "is the world of these norms" (76). Mattessich

265

266

CHRISTIANITY AND LITERATURE

uses Derrida to suggest that fire in Housekeeping works as a force that allows

Sylvie and Ruth to break free of the social norms of Fingerbone and al the

same time "fold them back into it" (76) as they become drifters in and around

it. Mattessich then demonstrates that Sylvie and Ruth have ambivalence

about the world. and he eventually argues Ihal Robinson shows that

"nuctuations of the spirit are at their Illost material and the sacred is indeed

acutest at its vanishing" (83). 1his sentiment is also true in Gilead, where

Ames understands his faith, his own spirit if you will, and the very essence

of others best when he is closest to losing his life and thus all connection

with them. Unlike HOllsekeepillg in which, as Mattcssich notes, fire docs not

enter until late in the novel, fire pops up everywhere in Gilead, from the

sermons in the attic to his grandfather's lctter that Ames burned, from the

Negro church to the fireflies in the yard. ~ Maltessich reminds us that, at the

end of HOllsekeeping, we never know "whcther the house survives the fire or

not" (76). The same is true of Ames' sermons and of the letter he is writing.

At the end of the novel, we come to the end of Ames' life, and Ames suggcsts

that Robert ask Lila to have the deacons arrange to "have those old sermons

of mine burned .... There are enough to make a good fire. I'm thinking

here of hot dogs and marshmallows, something 10 celebrate the first snow.

Of course shc can set by any of them she might want to keep" (Robinson,

Gilead 245). Just as we are unable to tell whether or not the house survives

the fire at the end of Housekeeping, we are unable to Icarn whethcr or not

Ames' sermons survive the fire he requests.

While fire in HOllsekeepillg becomes a symbol of bot h disenfranchisement

and power that changcs social norms and main characters, fire in Gilead

represents both the destructive forces of society and the power of the spirit,

in both the Holy Spirit of the triune God and the spirit of humanity, sent

by God and sharcd by peoplc. 111C Holy Spirit appears in Acts 2 on the day

of Pentecost as fire that rests on the apostles. That fire allows the apostles

to speak in tongues and spread the word of God. Without this gift of the

Holy Spirit, the apostles would be restricted to witnessing to those who

could understand their hlllguage. The fire of Pentecost is a contrary symbol

because it flames but does not burn. Likewise, the word of God shifts

throughout the triune God as it is eternal in the F,lIher, becomes flesh in the

son, and is spread by the Holy Spirit. Ames is keenly aware of the contraries

embodied in images and shifts of meaning in words. He realizes that, ifhis

son received his tetter, his son may not envision or interpret his words the

way he mcant them. For that matter, Ames seems aware thnt Jack Boughton

does not interpret his words the way Ames means, and that old Boughton

RACE AND THEOI.OGY I N GILEAD

267

may not either. Ames, too, (mis)reads the relationship between Lila and

Jack. His age and experience. howe\'er, do give him a bit of wisdom that he

could not have had as a younger man. And more importantly, he has belief,

faith in things unseen, including a faith that he is in a beautiful world that is

good because God made it so. Ames attempts to see and to help assuage the

pain of those around him, and he desperately looks for the good in all. Even

when he cannot see good directly, he seeks it. "I believe there are visions

that come to LIS only in memory, in retrospect. That's the pulpit speaking,

but it's telling the truth" (Gilead 91). In th is case, Ames is confident of the

success in his sermonic articulation of this idea. The mystery of it lies in

understanding the vision through memory. Memory is a construction. and

Ames hopes to const ruct love in the memories he has as well as those he

creates in th is letter, even as he acknowledges the difficulty in doing so.

Ames remarks, "Remembering and forgiving can be contrary things" ([64).

Remembering for Ames encompasses pains, griefs, and losses. His "endless

letter" both rejoices in the transcendent possibility of connecting with his

son after his death and is reminiscent of a jeremiad, as a long letter which

laments the loss of a relationship wit h hisson.) Ames' collection of memories

in his letter, however, ends wit h the promise of redempt ion. Ames is awa re

of the prophecy of the end times: "I suppose it's natural to think about those

old boxes of sermons upstairs. They are a record of my life, after all, a sort of

foretaste of the Last Judgment, really. so how can I not be curious?" (Gilead

41). Using language reflective of the sacrament of communion, in which

Christians receive a "foretaste of the feast to come," Robinson weaves in

apocalyptic language that smacks of both law and of gospel. rt is the record

of his life that would condemn it, but it is God's grace that would save it. As

George T. Montague explains when he traces images of the Holy Spirit from

its cleansing judgment in Isaiah, "When the Lord ... purges Jerusalem's

blood fro m her midst with the spirit of judgment and the spirit of fire" to

the New Testament images "which Jesus explains to the disciples of John the

Baptist that he has not come to apply the heavenly blow-torch to his people

but to proclaim the healing mercy of God" (40). lhllS, the fire of the Holy

Spirit in the O ld Testament judges, and the fi re of the Holy Spirit in the New

Testament transforms.

This mystery, the combination of judgment and grace, is embodied in

the contrary image offire throughout Gilead. Ames is surrounded by images

of sparks that Signal growing fire. Ames does not dwell directly on suffering

or lamentations, but his frustrations seep into his narrative as they are

268

CHRISTIANITY AND L I TERATURE

in herent in his memories and part of the record orhis life. He recalls a night

he and Boughton sat on the porch steps watch ing fireflies, and Boughton

remarked:

"Man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward:' And really, it was that

night as if the earth were smoldering. Well it was, and it is. An old fi re

will make a dark husk for itself and settle in on its core, as in the case

of this pbnet. I believe the same metaphor rna)' describe the human

individual, as well. Perhaps Gilead. Perhaps civilization. Prod a little

and the sparks will fly. (Gilead 72)

The burn ing of the Negro church, which he has reduced in his mind to

a small incident, the civil righ ts movement burgeoning in the south, and

a great many olher sparks glow around him. But unless he looks for them

or prods Ihem, he is unaware of such issues. He concerns himself with his

own worries, which are so narrow Ihal he covets the friendship his younger

wife has with Jack, even though Jack is wounded and wea ry, 3 nea rly broken

soul.

As Ames narrates the story of his life and ponders those around him. his

vision is fraugh t with fire, fire thai often represents annihi lat ion of sinners

and the painful loss of those who feel sin's gUilt and the loss of compassion

that such destruction leaves behind. These fire images are used in several

ways. First, the "rascally young fellows" joking after work are covered in

so much black grease and strong gasoline that Ames wonde rs "why they

don't catch fire themselves" (Gilead 5). Ames finds them a thi ng of beauty,

walking quotidian poetry. In contrast, Ames did not realize at Ihe time

how much anger there was in the fire that destroyed the Negro church. In

warning, he cautions his son, "A little too much anger, too often or at the

wrong ti me, can destroy more than you would ever imagine" (6). When

the church burned, Ames knew the fire was a serious wrong, but no one in

Gi lead could imagine the depth of pain it caused the families. No one cou ld

imagine the sins of the fathers falling as they do on Jack Boughton and his

wife and son, a mirror of Ames' own. Ames receives his wife and son late

in life and cannot believe they are his. Jack obtains his wife and son in the

prime of his life and also cannot believe they are his. Both, however, are

disallowed time to spend wilh their wives and sons. Jack and Ames both

end up disenfranchised from their families, Jack by society, and Ames by

age. 4 Ames is cognizant of the disconnect between himself and his son and

realizes the letter he is writing may not even reach its intended recipient.

Ames hopes, in language which echoes a Puritanical sermon, that the letter

might not be "lost or burned also" (40).

RACE AND THEOLOGY IN GlLEAD

269

Not only do Ames' words have the pOlential to be destroyed literally

because of fire. but words. even without malicious intent, can become

destructive like the church fire. Ames writes, "Above all. mind what you

say. 'Behold how much wood is kindled by how small a fire, and the tongue

is a fire'-that's the truth. When my father was old he told me that very

thing in a letter he sent me. Which. as it happened, I burned" (Gilead 6).

No wonder Ames considers that the letter he is writing may be burned. as

thai is exactly what he did with his father's letter. Ames seems aware of the

irony here and how hard it is for people to learn their lessons. Just before

Robinson introduces the first "Negro" in Ames' letter, Ames writes that

"one lapse of judgment can qUickly create a situation in which on ly foolish

choices are possible" (60). The fire set at the Negro church is the opposite

of the fire of the Holy Spirit. The destructive church fire is a representation

not of Christlike qualities but of the fa lse representation of God by humans

who made a bad choice. The novel is set in 1956. within two years of the

landmark case of Browl! V. Board of Education of Topeka and four years

after the publication of Ralph Ellison's I/lvisible Mall. Ames' letter does

not mention social changes in race relations. and he does not mention any

African American authors in his library, even when he describes orderi ng

more books than he ever had time to read. He has "mostly theology. and

some old travel books from before the wars" (77). The effects of the fire at

the Negro church have kindled results with fa r greater and more damaging

consequences than Ames realizes until the last section of the novel when

Ames begins to understand Jack's plight.

The tapestry in Ames' grandfather's church proclaimed, "The Lord Our

God Is a Purifying Fire" (Gilead 99). Ames writes about how angry his

father became because the congregants of that church justified the war wit h

that phrase. One woman even called it "just a bit of scripture" (99). Here.

Ames continues to explore the nature of how things mean. The people of

that church wanted to believe the war they were fighting was sanctioned

by God. and they even went so far as to create the gloriOUS tapestry to

celebrate God's glory in their fight. This sort of bloodshed, however, inflicts

the deep psychological and phYSical wounds that need the balm of Gilead

for healing. Just because people want to just ify things as God's will does not

make them so. Sometimes God is represented falsely by the church, and

such representations come out of man's inability to be p ure. ~ Ames felt he

had a special transcendent communion. a connecting experience with his

father after his grandfather's church burned. But as he describes the spiritual

way his fa ther fed him the biscuit with ash, Ames writes, "My point here is

270

CHRISTIANITY AND LITERATURE

that you never do know the actual nature even of your own experience"

(95). The church burned from a desire to control society and to control the

hegemony orthe lowll.TIle righteousness of their puritanical errand was a

self-glorification al best and a damning crime as viewed by anyone outside

their self-justified and self-serving missioll .

Even though he did not burn down the Negro church, Ames is guilty for

it, just as he waS drawn in to the things his grandfather did in Kansas. Ames

writes:

! was in on the secret, loo- implicated without knowing what I was

implicated in. Well, that's the human condition, I suppose. I believe

I was implicated, and am, and would have been if J had never seen

that pistol. [\ has been my experience that guilt can burst though the

smallest breach and cover the landscape, and abide in it in pools and

danknesses, just as native as water. (Gilead 82)

Ames sees the sins of the fathers fall upon him. Ames felt his father should

hide the gUilt of his father and that he should hide the guilt of h is, but he

reveals the rift and the fact that he kept the note his grandfather left. The rift

between father and son is emblematic oflarger rifts, for example, in society,

the rift of segregation and laws against miscegenation, and, in Christianity.

the rift of sin which separates man from paradise and from God. As people

are torn apart, those who cross social lines like Jack Boughton become

displaced and in a sense erased from both the white culture in towns like

Gilead and from black cultu re in cities like MemphiS. Once again, sin causes

consequences, not only in continued separation from God, but also in

separation from would-be earthly comfort such as family. 111e displacement

in both cases causes misunderstanding and confusion, leaving all in a world

where no one can see anyone else's situations or intents clearly.

Ames also experiences misunderstanding and confusion and seems

blind to the nature of his own experience when Jack visits his house. He

does not ask Lila about her past, and he misreads Jack's familiarity with Lila.

Ames is so concerned that Jack may take his place as husband and father

to them that he cannot see Jack's pain. He is aware of something amiss with

Jack. Ames says Jack has always looked to him "like a man standing too

dose to a fire, tolerating present pain, knowing he's a half step away from

something worse" (Gilead 191). Ames reads Jack's awkward and unsettled

nonverbal communication, but Ames does not interpret it correctly. Not

until the end of the novel, or even until the end of Home, does the reader

RACE AND THEOLOGY IN Gfl"EAD

271

have a strong idea of why Jack acts the way he does. In her introduction to

TIle Death of Adam, Robinson states:

Evidence is alway~ construed, and it is always liable to being

misconstrued no matter how much care is exercised in collecting and

evaluating it. At best, our understanding of any historical moment is

significantly wrong, and this should come as no surprise, since we have

little grasp of any given moment. The present is elusive (or the same

reasons as is the past. (4)

Robinson's characters often have little understanding of their own moments,

the moments of those they love, or of the moments of those they know more

remotely through connect ions in society. [n effect, they stand close to each

other, the way Jack stood too close to the fire, enduring pain-Jack enduring

the pain of courting damnation, and-those close to him enduring the pain

of not knowing how to understand what is right next to them. Jack's loved

ones try very hard in their own inefficient and unsatisfying ways to reach

out to him, to save him, their beloved prodigal. Their work appears to have

no effect, however, as Jack always falls back into the same patterns of sin

and continues to look like he's standing 100 dose to the fires of hell and

damnation . Jack is an everyman here, as all sinners are, the prodigal son

unable to make spiritual progress (to move away from fiery damnation)

without God's grace.

Fire in Gilead represents both the spiritual progress of the puritanical

errand into the wilderness to save those standing too close to the fires

of damnation and a herald of the civil rights movement. Robinson also

uses fire imagery to transcend those same painful earthly struggles and

offer hope of a new vision, the sort of loving transcendent vision Ames'

grandfather wrote about in the note he left on the kitchen table (Gilead 85).

At the end of the novel, Ames sees not only the fires of bell on earth but

also the fire of the righteous God. The ruins of courage and hope seem to

Ames but an ember, and be believes "the good Lord will surely someday

breathe it into flame again" (246). Gilead does not look like the floor of hell,

but it looks "like whatever hope becomes after it begins to weary a little,

then weary a little more. But hope deferred is still hope" (Robinson, Gilead

246). Robinson's language here not only references Provo 13: 12 but also

calls to mind Langston Hughes' "Harlem [21" in which Hughes asks, "What

happens to a dream deferred?" (426). The poem also inspired Lorraine

Hansberry to include it at the beginning of her play, A Raisill ill tile SI/II.

272

CH RISTIANITY AND LITERATURE

which takes its title from Hughes' third line of the poem and became the

first play by an African American woman to win the Drama Desk Award.

Robinson's words become yet another renecting mirror as she reminds

readers of the histories around words and persons, and how those histories

exist whether or nol they can be remembered or understood. Robinson

does no! leave Ames impotent in participating in these histories, evell if

he does not comprehend his ability to do so. He goes on immediately to

write, "I love Ihis town. [ think sometimes of going into the ground here as

a last wild gesture of love- I too will smolder away the time until the great

and general incandescence" (247). Thus, Ames is empowered with love, the

commandment of the gospel, to love his neighbor as himself, and Ames,

in the end, is able to feel that love. And for Robinson, love "is probably a

synonym for grace" (Robinson, "Further Thoughts" 488). Gilead may not

be the city on the hill, but Ames' final vision of it offers hope that people

could attain peace and grace in a new world and perhaps reflect some of

that future in the present. Ames is able to see and express his desire to offer

this "wild gesture of love" as he moves beyond the place Ihat most needs it.

It's easy to get bitter and resentful toward God like the Israelites Jeremiah

describes when people endure unceasing pain and incurable wounds. Jack,

with his doubts and his interminable suffering, epitomizes this waiting and

hoping state of humanity. Ames, on the other hand, knows he is 011 the

verge of exiling this world and is able to have a glimpse of the perspective of

leavi ng it behind.

Before that last moment, however, Ames has suffered with his ailing

heart and has already mourned the lossofhis wife and son when he imagines

Jack came home to take over his family. The suflering human, blinded by

pain, often misperceives God's intentions. In Jeremiah, God promises to

deliver the Israelites out of the hands of their enemies and to restore them

to him. If sinners return and repent, God will restore them and save them

and deliver them from what ails them. A righteous end would be payment

for sins, but God does not hold sin against the sinner who believes in Christ

and repents, who receives the "free grace of forgiveness" Boughton has

struggled with comprehending (Gilead 190). Believers, in turn, are filled

with a burning desire from the Holy Spirit to go Ollt and tell olhers so they,

too, can experience the same love and righteollsness. One day. and that day

comes soon for John Ames, believers will see and know God fully. no more

lenses, but face-to-face. Ames describes the phenomenon:

RACE AND THEOLOGY IN GILEAD

273

If the Lord chooses to make nothing of our transgressions, then they are

nothing. Or whatever reality they have is trivial and conditional beside

the exquisite primary fact of existence. Of course the Lord would wipe

them away, just as [ wipe dirt from your face, or lears. After all, why

should the Lord bother much over these smirches that are no part of

His Creation? ([90)

So, in Robinson's vision, being becomes more significant than how one is

being. Existence itselfis a miracle and part of tile celebration of the mystery

of God's grace.

Just as fire destroys in order to create energy, each bit of knowledge

and grace subverts the old to make the new. God's grace both crucifies and

creates a new self. As Vera J. Camden explains, "The anguish of men like

Luther and Bunyan-and many believers-is that the lived experience of

this paradox enforces a terrifying abjection, as the old self must be both

rejected and retained, the new self both embraced and anticipated."6

Perhaps subverting his old self to make way for a transformed self who

can connect with his son is part of what Ames hopes to do in writing this

letter. Certain ly, Ames comes close 10 transforming the sparks of fire. the

often misguided energies toward God's will: "The idea of grace had been so

much on my mind, grace as a sort of ecstatic fire that takes things down to

essentials" (Gilead 197). As Betty Mensch notes in her revie\'/ of Gilead and

JOllathall Edwards: A Life, Ames is a man who "once wrote a fiery Edwardslike sermon" and then "felt ridiculous:' which moved him toward "(I losing

his habits of judgment" (237). 1hat sermon is missing from the box in the

attic. Ames explains th,lI it is one he "actually burned the night before (hel

meant to preach it" (Gilead 41). He now regrets that it is lost: "I wish [had

kept it, because J meant every word. It might have been the only sermon

I wouldn't mind answering for in the next world. And I burned it" (43.)

Perhaps burning the sermon and haVing it only in his memory helps Ames

to imagine that it may have been a sermon to be proud of, one that may

have accomplished something worthy of God's attention. The fiery sermon

ends up in a fire, and only the fire which destroyed the sermon can make

the idea of the sermon one that might be somehow godly. The sermon

itself, however, focused only on humanity's damned nature, which is why

Ames burned it-to keep from hurting his congregation with more guih

and shame. Again, Robinson layers meanings offire to illustrate the human

cond ition and its inability to come to God on its own. Mensch reminds us

of the [ayers of contraries that are built into the entire town of Gilead and

274

CHRIST I AN IT Y AND L IT ERATURE

that "in scripture, Gilead is origin of prophecy, source of refuge, but also

object of prophetic condemnation" (237). Robinson embraces purifying

destruction and its promise of restoration and salvation in the city on the

hill, and she also encompasses a transcendent humanity. Such transcendent

hope comes not only from the sentiment of Ames' narrative, but also from

voices displaced into the margins of the text. While Ames looks forward

with hope to imminent transformations, Jack waits in the desert of time

before the civil rights movement. Even further oul in the margins are the

histories of the African -Americans who were enslaved.

Ames does not address it, but Robinson's title rings of the AfricanAmerican spiritual, "There Is a Balm in Gi lead";

There is a balm in Gilead

To make the wounded whole

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sin -sick soul

Sometimes [ feel discouraged

And think my work's in vain

But then the Holy Spirit

Revives my soul again

Don't e\'cr feel discouraged

For Jesus is your friend

And if you lack of knowledge

He'll ne'er refuse to lend

If you cannot preach like Peter

If you cannot pray like Paul

You can tell the love of Jesus

And say, "He died for all." (negrospirituals.com)

Gilead is mentioned twice in Jeremiah, both times in reference to its healing

balm. The spiritual lyrics end with a c<lllto w it ness, which is the legacy of

the jeremiad that promises the new covenant in the messiah. As Michael

Dirda indicates:

Gilead is a land east of the Jordan traditionally viewed as the source

of a healing salve: the balm of Gilead. But in the Old Testament this

same region carries less pacific associations as well and is sometimes

described as a place of war, bloodshed and iniquity. The word Gilead

is also linked - through a folk etymology- with the idea of witnessing.

(BW 15)

RACE AND THEOLOGY IN GILEAD

275

The healing balm of Gilead is close to the novel's foundation, one built

on recognizing the histories of strife and suffering in individuals and

communities, and one that transcends those struggles to celebrate the

loving connection in the f\llfillment of God's promise. Ames reaches thai

promise, or Promised Land, at his death, but he also offers hope for the

dream of harmony to become part of Gilead for his son and the generations

to come. In "Facing Reality~ Robinson suggests that to a large extent in

our present culture "the sense of sickness has replaced the sense of sin, to

which it was always near allied" (Death of Adam 83). She notes that some

antebellum doctors identified "an illness typical of enslaved people sold

away from their families which anyone can recognize as rage and grief" (83).

Surely this sin-sickness is the same type she describes in the plots of Gilead

and Home, each burdened with the disconnectedness of humanity, most

overtly in Jack's painful inability to find a place where he can live happily

together with his wife and chi ld. At the end of "Facing Reality:' Robinson

asks what would happen "if we understood our vulnerabilities to mean we

are human, and so are our friends and our enemies, and so are our cities and

books and gardens, our inspirations, our errors. We weep human tears, like

Hamlet. like Hecuba" (Adam 86). Read in this light. sin is no less painful,

sins such as slavery and racism are no less evil, and misjudging is no less

wrong; however. all sins are forgivable. even those that hurt most. Gilead

asks readers to understand and to forgive themselves, their loved ones, and

their enemies, and to rejoice in the beautiful humanity that can be found in

all people and all places, just as Ames so beautifully records himself doing

at the end of his letter.

I experienced a practical example of the novel's message when I used

Gilead in a composition class at a college that was experiencing a hostile

racial environment. During the class in which I introduced the lyrics and

music of "There Is a Balm in Gilead," my students, both black and while.

actually broke out into song, waved their arms above their heads, and leaned

their bodies back and forth as they sang the spiritual together. They repeated

the song until every student~including Christ ians. Buddhists, agnost ics,

atheists, and others without religious labels- was singing as one, moving

with the rhythm of the music and participating in the sea of hands and

weaving. Like Ames, I may have misread that classroom moment, wanting

so much to believe in the good and the healing. But, in that moment, unity

and love did exist. Olhers may not const ruct their memory of that class

276

CHRIST I ANITY AND L I TERATURE

the same way I do, but my memory of it is one of a mysterious uplifting

happiness. Robinson's novel asks readers to seek that kind of transcendent

joy, to look through a tens of love and acceptance and communion to strive

to see the good, the beauty. and the love, with whatever it takes to see that,

be it forgiveness. camaraderie, sol idarity, anything that allows a harmonious

community to transcend enmity between people, the iniquities thaI cause

rifts and morc sins against one another. Through Ames' celebration of

being, Gilead offers readers a hope of balm for issues that cut as deeply as

racial prejudice, a hope that all of us might understand ourselves and our

neighbors better, as we move toward communities of harmony.

Perhaps my students and I experienced a literary work's power 10 move

readers beyond its text, as Ann Hu lbert found herself moved at the end

of the novel. In her Slate review, Hulbert commenls on Robinson's final

sentiment: "What elicits tears at the book's close, I think, is a highly unusual

literary experience: Robinson (in her role as author of this creat ion) allows

even a faithless reader to feel the possibility of a transcendent order. thanks

to which mercy can reign among people on Earth" (Hulbert).' Robinson

offers in Ames a hope of finding a way to unite all people and of valu ing the

collective in his time of loss and mourning. The mystery and the beauty of

the collective is part of Ames' vision. Ames writes:

In every important way we are such secrets from each other, and I do

believe that there is a separate language in each of us, also a separate

aesthetics and a separate jurisprudence. Every Single one of us is a little

civilization built on the ruins of any number of preceding civil izations ...

all that reaUy just aUows us to coexist with the inviolable, untraversable,

and utterly vast spaces between us. (Gilead 197)

The space between our sepa rate bodies of laws, separate understandings

of truth and beauty, and our separate guilt and pains and sufferings all

come together in a transcendent understanding of the mystery of being and

how people exist at all, each person wi th his or her own "endless letter" of

memories, experiences, histories, desires, hopes, and dreams.

The separation itself becomes part of the solution instead of only the

problem; the inability to understand becomes part of the impetus to work

toward understanding. Ames remarks, " I don't know why solitude would

be a balm for loneliness, but Ihat is how it always was for me in those

days" (Gilead 18-19). Ames' description of this paradox leads the reader to

Robinson's vision of transcendence. When human beings come together,

RACE AND THEOLOGY IN GILEAD

277

as Ames is with Lila and their son, as Ames is with Boughton, as Ames is

with Jack, the distance between them is pronounced. The inability of human

beings to understand one another is painfully obvious. When alone, as Ames

is when he writes his letter, people can feel less lonely, because they are not

phYSically confronted with the terrible chasms of misunderstanding and

confusion between them, like the chasm between Ames' grandfather and

his father, like the chasm between Jack and his family. Ames' grandfather's

grave even holds the image of a chasm, as Ames says: "It was that most

natural thing in the world that my grandfather's grave would look like a

place where someone had tried to smother a fire" (SO). The presence of

physical bodies makes the space between them stand out in sharp relief.

When alone, individuals can imagine through the constructs of memory

that they touched someone, the way Ames believes his father touched him

with the ashy communion biscuit, the way Ames hopes to connect with his

son over the years, and the way Ames purports to connect with "his !lock."

As he explains to the reader, "This habit of writing is so deep in me, as

you will know well enough if this endless letter is in your hands" (Gilead

40). Although he cannot phYSically or literally span lime. Ames hopes his

record of thoughts and memories and love can reach his son through this

letter, full of both mourning over the fact that his life only eclipses his son's,

and full of hope that he can express what he intends to his son. Ames tells

his reader, "For me, writing has always felt like praying, even when I wasn't

writing prayers, as I was often enough. You feel like you are with someone"

(J 9). Perhaps one reason Ames writes as if he were praying is because he

faces such a great challenge in attempting to communicate with his son

and because he wants so badly for his communication to be Significant and

profound, a way to share thoughts about his life, his loves, and his values.

In Robinson's Christian vision, it seems one does not have to articulate

one's beliefs clearly, or even at all, in order to be saved. Just as fire can both

destroy and create anew, words can both damage people and help move

them toward understanding. Ames repeatedly comments on ways Lila is

not very articulate, and he recognizes that she is embarrassed by her poor

grammar and usage. On the other hand, he often also exclaims how well

she can articulate some of the deepest most complex ideas, especially those

about her salvation. In Home, Gilead's companion text about the same

characters from a different perspective set in the Boughton hOllse, Robinson

develops further the parable of the prodigal son which she begins in Gilead

to illustrate that, unlike the Puritan belief in the elect and one's assurance

of that position through one's articulation of one's beliefs, all are invited to

come 10 the river, not only those who attempt to articulate clearly the path

278

CHRISTI AN ITY AND L I TERATURE

10 get there. In Gilead, Robi nson uses Ames' voice to express with erudi te

fervor and from wise experience the ways a Christian lives in a world filled

with both menace and hope and is paradoxically saved not by his or her

own actions but passively by the very nature of God's grace.

When fire imagery interplays with racial conflicts in the civil rights era

in this novel, it reveals disconnects between characters and ideas, especially

between characters who long to be toget her, such as Ames and Robert, as

well as Jack and both his families. Robi nson reflects in a varietyo( characters

the desire to be understood. Just as Ames repeatedly wishes his son Robert

can understand and can see what he means, so his namesake, Jack, also

wishes he could be seen and understood. Ultimately, Ames offers hope for

understanding as a spiritual fire that is present in all: "When people come

to speak to me, whatever they say. I am struck by a kind of incandescence

in them, the 'J' like a flame on a wick, emanating itself in grief and guilt and

joy and whatever else" (Gilead 44-45). Here, fire re-presents the Christlike

qualities Ames seeks to model in his behavior. It seems simplistic to sllggest

that Ames is witnessing, but just like the spiritua l, "There Is a Balm in

Gilead:' Ames dips into his own civilizatio n and unites with all the other

fiery wicks to glow together in a spiritual incandescence of jere miad ic

drama~a perpetual destruction and reconstruction, with all the mystery

ofils inex pl icable separation and restoration. Robinson's use offire imagery

to illustrate the conflicti ng mysteries of both a doomed and suffering world

as well as the fervent gospel of divine grace helps build her C hristian vision,

which, in Gilead, glories in the lamentations of human existence and the

hope of fulfilling the meani ng of that existence with the promise of a new

covenant, one which becomes miraculous in the very fact that it exists.

Indiana UniverSity-Purdue University Columbus

NOTES

'For an overview of research on the Holy Spirit, see Hinze and Dabney's Ad\'ellls

oflhe Spirit. George T Montague's ch3pter, ~The Fire in the Word: The Holy Spirit

in Scriptu re" offers a summary of ways the Holy Spirit is represented in biblic3l

images. He lists the Holy Spirit's appear3nces 3S fire, which culminate in Pentecost

(40).

lAs Robinson uses 1956 conventions for referring to this congregation,

so J preserve the use of "Negro" when referring to this congregation and her

characters.

)While J do not have space to build the argument here, I see Gilead as ajeremiad

RACE AND THEOl.OGY IN GILEAD

279

in the double sense, both a long letter of complaint and mourning which culminates

in transcendence, and as a novel that participates in the tradition of the American

Jeremiad, defined and developed by Perry Miller in TIle Nell' ElIglami Milld; from

CololIY to Provillce and Sacvan Bercovitch's TI,e Americall Jeremiad. For a general

survey of Puritan writings, see Emory Elliot's "/Ie Cambridge Introduction to Ear/y

American Literature, and note page 16 of his introduction where he concisely

defines the jeremiad within the larger traditions. See also Betty Mensch's review

of Gilead and George M. Marsden's biography of Jonathan Edwards in which she

traces ways Gilead is about Edwards and relates to his "objective reality:' I am not

trying to engage fully the sermon genre of the jeremiad in this essay, but I do wish

to use it to help me suggest a connection between the fire imagery and the spiritual

meanings of the novel.

' For an analysis of the myth of the jeremiad for African Americans, see David

Howard-Pitney, TI,e Afro-AmericclIJ Jeremiad; Appell/sfor Juslice ill America.

sSacvan Bercovitch \."rites, "Replica or mirror-reflection , representation or

re-presentation: the "or~ makes all the difference in the world. More precisely, it

marks the difference between this world and the next. And yet the two kinds of

speech are as close as "like" and "alike." They are complementary pieces in the

same game, like rook and bishop. They work together on the premise that their

functions are distinct. [n order to make this as clear as possible, Church authorities

from Augustine through Aqu inas made that distinction (representation or re

presentation) a central tenet of Christian hermeneutics. By that rule Luther denied

the Pope's right to stand in for Christ. The Holy Roman Empire, he charged, was

a replica of the true church, not a re-presentation of it. The fact that it claimed to

re-present the true church made it a fa lse replica, hence the Antichrist incarnate.

By that rule, too, Milton justified regicide by appealing directly to Christ, the true

mirror-reflection of God as king as Charles [ (in his view) was emphatically not.

The fact that Charles claimed divine right disqualified him as representative of

heaven's king. It is not too much to say that the hermeneutics of like-versus alike

became a vehicle of theological and social transformation. Understandably, the

Reformers were charged with blasphemy -- appropriately they called themselves

Protest ants, Dissenters -- but so far as they were concerned, they had come to fulfill

the exegetical law, not to break it" CA Mode[ ofCu[tura! Transva[uation~).

6Camden points to Julia Kristeva's revisions of Jaques Lacan to support the

paradox.

' Not all reviewers find Gilead inspirational or transcendent. In his review for

the Seallle TImes, Robert Allen Papinchak calls Ames one-dimensional and his

narrative bland and unengaging.

WORKS CITED

Bercovitch, Sacvan. "Iile America" Jeremiad. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1978.

_ . ''A Model of Cultural Transvaluation: Puritanism, Modernity, and New

World Rhetoric:' <http://web.gc.cuny.edu/ deptlrenail conO Papersl Keynotel

280

C H RIS TI AN I TY AND LI TERATU RE

Bercovit.htm >. 2 J December 2009.

Camden, Vera /. "'Most Fit for a Wounded Conscience': The Place of Luther's

'Commentary on Galatians' in Grace Abounding." Renaissal1ce Quarterly

50.3 (1997): SJ9 -49.JSTOR. Web.

Dirda, Michael. ~Gilead." Rev. of Gilctld by Marilynne Robinson. Was/lillgloll Post.

21 Nov. 2004; BW 15. Web. 22 December 2009.

Elliot, Emory. JJ/C Cambridge Introduction to Early American Litera/lire. New

York: Cambridge UP, 2002.

Hansberry, Lorraine. A Raisin ill file SUII. 1958. New York: Vintage, 1994.

Hinze, Bradford E., and D. Lyle Dabney, cds. Adl'enrs of tile Spirit: Al/ll1troduction

10 the Currellt Study of PIJcllmatology. Milwaukee: Marquette Up, 2001.

Howard- Pitney, David. 711e Afro-American jeremiad: Appeals for justice in

America. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2005.

_."The Enduring Black Jeremiad: TIle American Jeremiad and Black Protestant

Rhetoric, from Frederick Douglass to W. E. B. Du Bois, 184 1- 1919:'

American Qllarterly 38:3 (1986): 481 -492.

Hughes, Langston.

Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Eds. Arnold

Rampersad and David Roessel. New York: Knopf, 1995.

Hulbert, Ann. "Amazing Grace: The Extraordinarily Suspenseful Beauty

of Marilynne Robinson's Gilead." Rev. of Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Slate

Magazine. 6 Dec. 2004. Web.

Mattessich, Stefan. "Drifting Decision and the Decision to Drift: The Question

of Spirit in Marilynne Robinson's HOllsekeeping." Differences: A ]ollrllal of

Feminist Cllllllmi Studies 19.3 (2008): 59-89.

Mensch, Betty. "Jonathan Edwards, Gilead, and the Problem of'Tradition:"

Rev. of Gilelld by Marilynne Robinson and JOl1athal1 Edwards: A Life by

George M. Marsden. jOl/mal of Law (lmi Religion 21.1 (2005/2006): 221-41.

Miller, Perry. Errand illio Ilu.' lViidemess. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1956.

_ . 71Je New Englmul Mil1d:from Colony 10 Provillce. Boston: Beacon, 1961.

Montague, George T. "The Fire in Ihe Word: The Holy Spirit in Scripture."

'n,t

Advenls of the Spirit: All IntrodllCtiol1

10

Ihe Current Stl/dy of Pllel/matology.

Eds. Bradford E. Hinze and D. Lyle Dabney. Milwaukee: Marquette UP, 2001.

35-65.

negrospirituals.com. Web. 22 December 2009.

Papinchak, Robert Allen. "Gilead: A Somber Life, an Unengaging Narrative."

Rev. of Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Seatlle Times 21 Nov. 2004.

Robinson, Marilynne. 'J11e Deatli of Adam. New York: Picador, 1998.

_."Further Thoughts on a Prodigal Son who Cannot Come Home, on

Loneliness, and Grace." Interview by Rebecca M. Painter. Chrislimlily and

Litemlllre. 58 (2009): 485-92.

_ . Gilead. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 2004.

_ . Home. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 2008.

_ . Housekeepillg. New York: Picador, 1981.

Shea, Lisa. "American Pastoral." Rev. of Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Elle 20.3

(Nov. 2004): 170.

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Title: Fraught with Fire: Race and Theology in Marilynne Robinson's Gilead

Source: Christ Lit 59 no2 Wint 2010 265-80

ISSN: 0148-3331

Publisher: Christianity and Literature

Humanities Division, Pepperdine University, 24255 Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu,

CA 90233

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced

with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is

prohibited. To contact the publisher: http://www.calvin.edu/academic/engl/ccl/index

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sublicensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make

any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently

verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever

caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

You might also like

- Cardinal Bernardin's Stations of the Cross: Transforming Our Grief and Loss into a New LifeFrom EverandCardinal Bernardin's Stations of the Cross: Transforming Our Grief and Loss into a New LifeNo ratings yet

- Homage to a Broken Man: The Life of J. Heinrich Arnold - A true story of faith, forgiveness, sacrifice, and communityFrom EverandHomage to a Broken Man: The Life of J. Heinrich Arnold - A true story of faith, forgiveness, sacrifice, and communityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Opening the Treasure of the Scriptures: Some Biblical CrumbsFrom EverandOpening the Treasure of the Scriptures: Some Biblical CrumbsNo ratings yet

- Riding with the King: The Jack Sutherington Series - Book IIIFrom EverandRiding with the King: The Jack Sutherington Series - Book IIINo ratings yet

- Harvest: Book III of the Trilogy Renaissance: Healing the Great DivideFrom EverandHarvest: Book III of the Trilogy Renaissance: Healing the Great DivideNo ratings yet

- Mind Soul Ink Paper (and Other Essays On Faith, Reading, and Writing)From EverandMind Soul Ink Paper (and Other Essays On Faith, Reading, and Writing)No ratings yet

- Searching for Mrs. Oswald Chambers: One Woman's Quest to Uncover the Truth about the Woman behind the Most Celebrated Devotional of ...From EverandSearching for Mrs. Oswald Chambers: One Woman's Quest to Uncover the Truth about the Woman behind the Most Celebrated Devotional of ...Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Fire and Spirit: Inner Land – A Guide into the Heart of the Gospel, Volume 4From EverandFire and Spirit: Inner Land – A Guide into the Heart of the Gospel, Volume 4No ratings yet

- Tragedy of the Commons: A Christological Companion to the Book of 1 SamuelFrom EverandTragedy of the Commons: A Christological Companion to the Book of 1 SamuelNo ratings yet

- New Testament Micro-Ethics: On Trusting Freedom: The First Christians’ Genotype for Multicultural LivingFrom EverandNew Testament Micro-Ethics: On Trusting Freedom: The First Christians’ Genotype for Multicultural LivingNo ratings yet

- Two Sisters in the Spirit: Therese of Lisieux and Elizabeth of the TrinityFrom EverandTwo Sisters in the Spirit: Therese of Lisieux and Elizabeth of the TrinityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The Best of J. Ellsworth Kalas: Telling the Greatest Story Ever Told Like It's Never Been Told BeforeFrom EverandThe Best of J. Ellsworth Kalas: Telling the Greatest Story Ever Told Like It's Never Been Told BeforeNo ratings yet

- God Is Not Fair, Thank God!: Biblical Paradox in the Life and Worship of the ParishFrom EverandGod Is Not Fair, Thank God!: Biblical Paradox in the Life and Worship of the ParishNo ratings yet

- Religion - A Friend in the Library: Volume VIII - A Practical Guide to the Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell HolmesFrom EverandReligion - A Friend in the Library: Volume VIII - A Practical Guide to the Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell HolmesNo ratings yet

- The Triumph of the Gospel in the Sacristan's Home: A Novel Based on a True StoryFrom EverandThe Triumph of the Gospel in the Sacristan's Home: A Novel Based on a True StoryNo ratings yet

- Beyond Words: Daily Readings in the ABC's of FaithFrom EverandBeyond Words: Daily Readings in the ABC's of FaithRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Imaging the Story: Rediscovering the Visual and Poetic Contours of SalvationFrom EverandImaging the Story: Rediscovering the Visual and Poetic Contours of SalvationNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 04, No. 22, August, 1859 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsFrom EverandThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 04, No. 22, August, 1859 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- The Hereditary Evil in "East of Eden"Document6 pagesThe Hereditary Evil in "East of Eden"sarmis2No ratings yet

- Barry Jacobs-Titanism and Satanism in To Damascus IDocument23 pagesBarry Jacobs-Titanism and Satanism in To Damascus IZizkaNo ratings yet

- (ARTIGO) HÃ - LTGEN, K J (2002) William Blake and The Emblem TraditionDocument9 pages(ARTIGO) HÃ - LTGEN, K J (2002) William Blake and The Emblem TraditionFernando NascimentoNo ratings yet

- The Magic Glass in The Magic Land - Navigating Ishmael's BookDocument44 pagesThe Magic Glass in The Magic Land - Navigating Ishmael's Bookfjestefania6892No ratings yet

- Universitatea Din Craiova, Master, Studii de Limbă Și Literaturi Anglo-Americane Anul Ii, Semestrul Ii Craiova, Mai 2019Document6 pagesUniversitatea Din Craiova, Master, Studii de Limbă Și Literaturi Anglo-Americane Anul Ii, Semestrul Ii Craiova, Mai 2019Consuela BărbulescuNo ratings yet

- Robert Burns "Holly Willie's Prayer" & "To A Mouse"Document42 pagesRobert Burns "Holly Willie's Prayer" & "To A Mouse"AnaMaraLeoNo ratings yet

- Toni Morrison Beloved Christian AllegoryDocument20 pagesToni Morrison Beloved Christian Allegorygitarguy18100% (1)

- A New Mode of PrintingDocument4 pagesA New Mode of PrintingBelén TorresNo ratings yet

- Spiritual StrengthsDocument3 pagesSpiritual StrengthsDamilola AladedutireNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument2 pagesCurriculumVillanovaLibraryNo ratings yet

- (Terry L. Cook) Big Brother NSA Its Little BrothDocument427 pages(Terry L. Cook) Big Brother NSA Its Little BrothPaulo SantosNo ratings yet

- Preparation For DeliveranceDocument4 pagesPreparation For DeliveranceETHAN COLLEGE OF BIBLICAL STUDIESNo ratings yet

- Kenneth E Hagin - Leaflet - The Individual's FaithDocument6 pagesKenneth E Hagin - Leaflet - The Individual's FaithAnselm Morka100% (1)

- The Kingdom of GodDocument4 pagesThe Kingdom of GodAnjang SimpuruNo ratings yet

- Evangelism ActivationsDocument8 pagesEvangelism ActivationsCristian ArrejinNo ratings yet

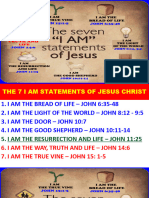

- 1 Jesus I Am The BreadDocument61 pages1 Jesus I Am The BreadRyan BriolNo ratings yet

- A Brand New StarDocument8 pagesA Brand New StarPaul HardingNo ratings yet

- Was The "Last Supper" The Passover Meal?Document6 pagesWas The "Last Supper" The Passover Meal?Bryan T. HuieNo ratings yet

- ART191 Review 7Document5 pagesART191 Review 7DazaiNo ratings yet

- Healing Is The Childrens BreadDocument130 pagesHealing Is The Childrens Breadjvassal100% (2)

- Anderson, Robert - The Honour of His Name (B)Document30 pagesAnderson, Robert - The Honour of His Name (B)Jack NikholasNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument16 pagesReflectionJK BC100% (1)

- French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte's IslamDocument12 pagesFrench Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte's Islamsamu2-4uNo ratings yet

- Islam and Christianity - Ahmed Deedat and Gary MillerDocument32 pagesIslam and Christianity - Ahmed Deedat and Gary MillerShehmir ShahidNo ratings yet

- Developing Youth MinistryDocument314 pagesDeveloping Youth MinistryApril ShowersNo ratings yet

- A Valentine Letter To JesusDocument3 pagesA Valentine Letter To JesusLiaPatolaNo ratings yet

- Applause, Waiving, Drumming, & Dancing in The ChurchDocument14 pagesApplause, Waiving, Drumming, & Dancing in The ChurchKhwezi ToniNo ratings yet

- The Subversive Use of Gnostic Elements in Jorge Luis Borges' Los Teologos and Las Ruinas CircularesDocument13 pagesThe Subversive Use of Gnostic Elements in Jorge Luis Borges' Los Teologos and Las Ruinas CircularesIan David Martin100% (2)

- Fearing GodDocument5 pagesFearing GodAnonymous d79K7PobNo ratings yet

- Not A Fan by Kyle Idleman, ExcerptDocument23 pagesNot A Fan by Kyle Idleman, ExcerptZondervan100% (2)

- Origins of World ReligionsDocument33 pagesOrigins of World ReligionsRicky Canico ArotNo ratings yet

- John 1:1-18 - Bible Commentary For PreachingDocument10 pagesJohn 1:1-18 - Bible Commentary For PreachingJacob D. GerberNo ratings yet

- The Glory ... The Presence ... of GodDocument78 pagesThe Glory ... The Presence ... of GodDr. A.L. and Joyce Gill100% (6)

- The Course of Love by Alain de BotonDocument162 pagesThe Course of Love by Alain de BotonAlex KataNa75% (4)

- Sermon Notes: "The Anatomy of Sin's Seduction" (James 1:13-15)Document3 pagesSermon Notes: "The Anatomy of Sin's Seduction" (James 1:13-15)NewCityChurchCalgaryNo ratings yet

- Dying Out?: Is ReligionDocument16 pagesDying Out?: Is ReligionSam LibresNo ratings yet

- Tehnici Si Exercitii SpiritualeDocument152 pagesTehnici Si Exercitii SpiritualeOdette Irimiea100% (1)

- Counselling in Holy SpiritDocument21 pagesCounselling in Holy SpiritolawedabbeyNo ratings yet