Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday'4777

Uploaded by

nabsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday'4777

Uploaded by

nabsCopyright:

Available Formats

6/7/2015

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday

The American Banking System

Might Not Last Until Monday

Alex J. Pollock

August 23, 2014 3:00 am | The American

How good is the human group mind at financial memory? Pretty bad.

For example, consider this really striking bit of history: The then Federal

Reserve Chairman made a phone call to the Bank of Japan Governor on that

critical Friday night (Saturday in Japan) in August of that year. The chairmans

first words were that the American banking system might not last until Monday.

The crisis was that serious.

Financial history quiz: Which year was that? What was the crisis? Who was the

Federal Reserve chairman making such an extreme statement?

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-until-monday/print/

1/5

6/7/2015

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday

Hint: our most recent financial crisis, which started in August 2007 (already

seven years ago this month) is not the crisis in question.

The right answers are: 1982. The global sovereign debt crisis, also known as

the LDC (less-developed country) debt crisis. The Fed chairman was Paul

Volcker. How did you do?

The Volcker quotation is from Richard Koos interesting 2003 book, Balance

Sheet Recession (I left the names out of the quote so as not to give away the

answer). Koo, who was the head of the International Financial Market Section of

the New York Federal Reserve Bank at the time, recalls how hundreds of

American banks, including all the big banks, along with banks in Japan, Canada,

and Europe, had been on a lending spree to the governments of less developed,

or as we would now say, emerging, countries. The Fed at the time estimated

that as many as a thousand U.S. banks had loans to Mexico alone.

This disastrous lending spree had been

widely and highly praised as recycling petro

dollars, displaying the typical inability to see

the financial future. By May 1982, the Fed was

already making special inter-central bank

loans to Mexico on financial reporting dates.

This gave the appearance of adequate

currency reserves at the Bank of Mexico,

according to Allan Meltzer in his definitive A

History of the Federal Reserve. But, in August

1982, with the default of Mexico, it became

obvious that the indebted governments could

not pay their debts, and therefore, Koo

writes, the big U.S. banks were all virtually

bankrupt.

At the very same time, the until then

dominant home mortgage source, the savings

and loan industry, was in the aggregate also

bankrupt. Quite a combination!

But there was more: also at that time, two big

bubbles were deflating: the oil bubble and

the farmland bubble. So not only were the

S&Ls on their way to their ultimate $150

billion taxpayer bailout, but nine out of the

nine biggest banks in Texas failed in the

1980s, along with a great many others, and

so did the Federal Farm Credit System, a

government-sponsored enterprise, which

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-until-monday/print/

Not only

were the

S&Ls on their

way to their

ultimate

$150 billion

taxpayer

bailout, but

nine out of

the nine

biggest

banks in

Texas failed

in the 1980s,

along with a

great many

others, and

so did the

Federal Farm

Credit

System.

2/5

6/7/2015

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday

ended up with its own congressional bailout.

As Chairman Volcker made his call to the

Bank of Japan, a most painful decade for the

banking system was under way.

Here is another financial history quiz: How many U.S. commercial banks, not

counting savings and loans and other thrift institutions, failed or had to get

government assistance in that eventful decade of financial unraveling from

1982 to 1992? Before you read the answer, whats your number?

The right answer is: 1,476 commercial banks failed. That is an average of over

130 per year, continued over 11 years. That is in addition to 1,332 thrifts, for a

total of 2,808 American busted depository institutions in the decade. If you

guessed wrong, you are in the majority: only two decades later, hardly anyone

knows this.

With this time of immense and intense troubles looming, what did Chairman

Volcker do to confront the massive amount of bad loans the banks had made to

the governments of LDCs and the corresponding, by then unavoidable, losses?

Face the facts and take the write-downs? Mark the loans to market? Try to

reduce the credit exposure to these insolvent borrowers? Have a stress test?

What do you think he did?

The correct answer is: None of the above. Indeed, he did just the opposite. As

Koo relates, On the day the crisis erupted, we received a personal instruction

from Paul Volcker. His instruction stunned us. It basically said, Whatever it

takes, make sure that U.S. banks stay on in Latin America and keep lending.

Dont give the banks excuses to flee. In other words, lets send some good

money after the bad.

With this surprising instruction, Koo continues, We had to call on each of

hundreds of banks in the United States, asking them not only not to recover

funds from Latin America but also to continue lending. His job at the time, he

relates, was to produce a list of all the U.S. banks with an exposure of more

than $1 million to Mexico. That list was then given to the district Federal

Reserve Banks so that the officers could contact these banks and try to persuade

them to keep lending. He was privately outraged, says Koo, but he was not

the boss of the Fed or of the convoy of hundreds of banks being commanded

by Fleet Admiral Volcker.

How about telling the truth of what was happening with accounting and

financial reporting? Well: Volcker had ordered the three bank supervising

authorities in the United States not to treat those loans as non-performing

loans in spite of the obvious fact that they were non-performing loans. If

they had declared them to be non-performing loans if they had stated the

truth, in other words the banks would have had an excuse to flee.

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-until-monday/print/

3/5

6/7/2015

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday

Recognition of the billions in credit losses was pushed off for several years.

In 1989, the Brady Bonds, creatively designed under the direction of then

secretary of the Treasury Nicholas Brady, were introduced to refinance the old

bad loans: in accepting the new bonds in exchange for the old loans, banks

typically recognized losses of 30 cents to 50 cents on the dollar. Writing in the

same year, economist John Makin estimated the average market value of LDC

loans as 35 cents on the dollar. This is a number not very different from the

recovery on defaulted subprime loans a generation later.

But before that, the financial authorities in

the United States streamrollered through,

declaring that loans to Latin American were

not non-performing loans and forcing the

banks to continue to lend. This history, so

interestingly related from personal

experience by Koo, displays a distinctly bold

strategy and a very high-stakes gamble by

the forceful Chairman Volcker. He got away

with it, while the hapless regulator of the

savings and loans, the Federal Home Loan

Bank Board, also made big gambles, but lost

them, and finally was abolished by Congress

in 1989. (Do you remember that there was a

Federal Home Loan Bank Board?)

By the late 1980s, when the LDC losses were

finally being recognized (on a mark-tomarket basis, which was pointedly not used,

they had existed for years), it appeared that

the commercial banks were once again

profitable and could absorb the losses.

One more financial history quiz: what was the

big new banking growth business of the

1980s, which was generating a lot of

apparent renewed banking profitability?

In August

1982, with

the default of

Mexico, it

became

obvious that

the indebted

governments

could not

pay their

debts, and

therefore the

big U.S.

banks were

all virtually

bankrupt.

The correct answer is: commercial real estate loans. This market in turn went

bust in 1990-91, causing huge losses and a renewed bout of bank failures. Real

estate loans had succeeded LDC loans as the biggest banking problem. Only a

couple of years after that, and only 12 years after 1982, Mexico was in trouble

again, with the Mexican Debt Crisis of 1994.

What can we learn from these largely forgotten but very instructive events, as

we give a vote of thanks to Richard Koo for his vivid reminder of them? When

faced by a banking system that might not last until Monday, powerful central

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-until-monday/print/

4/5

6/7/2015

The American Banking System Might Not Last Until Monday

bankers and governments will do whatever they think they need to. This can

include cooking the books, ordering around private parties as governments turn

to coercion, and sending good money after bad, all in the hope of bridging the

crisis. In time, the crisis does pass and losses are taken. Life goes on. Memories

fade.

The next crisis arrives as a surprise.

Ale x J. Pollock is a re side nt fe llow at the Ame rican Ente rprise Institute

(http://w w w .ae i.org/). He w as pre side nt and CEO of the Fe de ral Home

Loan Bank of Chicago 1991-2004.

FURTHER READING: Pollock also writes If Detroits Not Too Big To Fail, The Federal

Reserves Second 100 Years (http://www.aei.org//article/economics/monetarypolicy/federal-reserve/the-federal-reserves-second-100-years/), Coins That Go

Clunk, and Goodbye, Gold Redemption of the Dollar

(http://www.aei.org/publication/goodbye-gold-redemption-of-the-dollar/).

Image by Dianna Ingram/ Bergman Group

This article was found online at:

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-untilmonday/

http://www.aei.org/publication/the-american-banking-system-might-not-last-until-monday/print/

5/5

You might also like

- The Last Gold Rush...Ever!: 7 Reasons for the Runaway Gold Market and How You Can Profit from ItFrom EverandThe Last Gold Rush...Ever!: 7 Reasons for the Runaway Gold Market and How You Can Profit from ItNo ratings yet

- The Money Changers - Carmack Patrick S. JDocument27 pagesThe Money Changers - Carmack Patrick S. Jjaime.bvr7416100% (1)

- The Money ChangersDocument37 pagesThe Money Changerspaliacho77No ratings yet

- The Money ChangersDocument27 pagesThe Money Changersanon-881710100% (14)

- Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of DestructionFrom EverandCornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of DestructionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Andreas Whittam Smith: We Could Be On The Brink of A Great DepressionDocument4 pagesAndreas Whittam Smith: We Could Be On The Brink of A Great DepressionBarbosinha45No ratings yet

- Summary: I.O.U.: Review and Analysis of John Lanchester's BookFrom EverandSummary: I.O.U.: Review and Analysis of John Lanchester's BookNo ratings yet

- Bordo Crises and CapitalismDocument3 pagesBordo Crises and CapitalismecrcauNo ratings yet

- 2009 Winter Warning Volume 12 Issue 1Document4 pages2009 Winter Warning Volume 12 Issue 1ZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Bailout: An Insider's Account of Bank Failures and RescuesFrom EverandBailout: An Insider's Account of Bank Failures and RescuesNo ratings yet

- Jackson, Biddle, and The Bank of The United StatesDocument23 pagesJackson, Biddle, and The Bank of The United Statesalan orlandoNo ratings yet

- The Money Masters PDFDocument31 pagesThe Money Masters PDFvenurao1100% (6)

- Nothing Is Too Big to Fail: How the Last Financial Crisis Informs TodayFrom EverandNothing Is Too Big to Fail: How the Last Financial Crisis Informs TodayNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Banking FinalDocument7 pagesEvolution of Banking FinalDouglasNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Credit CrisisDocument31 pagesAnatomy of A Credit CrisisVikas KapoorNo ratings yet

- The Grave Importance of Ending The Financial Rule of The Federal Reserve and Central BankingDocument20 pagesThe Grave Importance of Ending The Financial Rule of The Federal Reserve and Central BankingJohn Gary Whalen JrNo ratings yet

- The Wall Street Journal Guide to the End of Wall Street as We Know It: What You Need to Know About the Greatest Financial Crisis of Our Time—and How to Survive ItFrom EverandThe Wall Street Journal Guide to the End of Wall Street as We Know It: What You Need to Know About the Greatest Financial Crisis of Our Time—and How to Survive ItNo ratings yet

- Jim Grant Why No OutrageDocument4 pagesJim Grant Why No OutrageCharlton ButlerNo ratings yet

- Dont Cry For Me Argent in ADocument12 pagesDont Cry For Me Argent in AhwaagNo ratings yet

- Money MastersDocument108 pagesMoney Mastersapanisile14142100% (1)

- Final Days of The Dollar 11 22 10Document13 pagesFinal Days of The Dollar 11 22 10exDemocratNo ratings yet

- (English) How The Federal Reserve Works (And Who Really Owns It) (DownSub - Com)Document7 pages(English) How The Federal Reserve Works (And Who Really Owns It) (DownSub - Com)Anastasia ZykovaNo ratings yet

- Latin American Debt Crisis of The 1980sDocument4 pagesLatin American Debt Crisis of The 1980sSyafikah KunhamooNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Credit CrisisDocument39 pagesAnatomy of A Credit CrisisrobertfilmerNo ratings yet

- Surviving A Global CrisisDocument98 pagesSurviving A Global CrisisCristiano Savonarola100% (1)

- Why Banke... R Westley - Mises DailyDocument3 pagesWhy Banke... R Westley - Mises DailysilberksouzaNo ratings yet

- David Icke - Federal Reserve System FraudDocument37 pagesDavid Icke - Federal Reserve System Fraudrrpena5520100% (1)

- 21st Century Global EconomicsDocument9 pages21st Century Global EconomicsMary M HuberNo ratings yet

- After The Music Stopped,' by Alan S. Blinder - NYTimesDocument3 pagesAfter The Music Stopped,' by Alan S. Blinder - NYTimesvineet_bmNo ratings yet

- The Federal Reserve Is A Private CorporationDocument31 pagesThe Federal Reserve Is A Private CorporationGuy Razer100% (1)

- 601 PrivateControlOfMoney1Document7 pages601 PrivateControlOfMoney1hanibaluNo ratings yet

- Rev 4 BenDocument5 pagesRev 4 Benapi-317092002No ratings yet

- Imani vs. Federal Reserve BankDocument163 pagesImani vs. Federal Reserve BankaminalogaiNo ratings yet

- The Federal Reserve: Dear AmericanDocument19 pagesThe Federal Reserve: Dear Americanjethro gibbins100% (2)

- Excerpt from "After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead" by Alan Blinder. Copyright 2013 by Alan Blinder. Reprinted here by permission of Penguin Press. All rights reserved.Document8 pagesExcerpt from "After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead" by Alan Blinder. Copyright 2013 by Alan Blinder. Reprinted here by permission of Penguin Press. All rights reserved.wamu8850No ratings yet

- Confidence in The EnemyDocument2 pagesConfidence in The EnemySamuel RinesNo ratings yet

- Cart Eliza Ti OnDocument48 pagesCart Eliza Ti OnGreg PassmoreNo ratings yet

- Debt Dynamite DominoesDocument46 pagesDebt Dynamite DominoesRedzaNo ratings yet

- Economics PPT: Group MembersDocument6 pagesEconomics PPT: Group MembersAhmarNo ratings yet

- The PrivateerDocument12 pagesThe Privateersloonie100% (1)

- The Money MastersDocument41 pagesThe Money Mastersjoan marie supsup100% (1)

- Rough Draft 2Document21 pagesRough Draft 2api-356190107No ratings yet

- Keynesian Economics Doesn't WorkDocument9 pagesKeynesian Economics Doesn't WorkkakeroteNo ratings yet

- Federal Reserve SystemDocument5 pagesFederal Reserve SystemladyjemnttNo ratings yet

- The Economist - Finacial CrisisDocument4 pagesThe Economist - Finacial CrisisEnzo PitonNo ratings yet

- Punishing Victims by Robert GroverDocument7 pagesPunishing Victims by Robert Groveradya_tripathiNo ratings yet

- BootymeatDocument24 pagesBootymeatapi-237179757No ratings yet

- 2020-07-20 The US Banking System-Origin, Development, and RegulationDocument6 pages2020-07-20 The US Banking System-Origin, Development, and RegulationD. BushNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: The Role of Financial Regulation: Background ContextDocument3 pagesUnit 1: The Role of Financial Regulation: Background ContextchiranshNo ratings yet

- Big Picture: Reflections, Assessments, Outlook, ApproachDocument17 pagesBig Picture: Reflections, Assessments, Outlook, ApproachHenry BeckerNo ratings yet

- Did You KnowDocument18 pagesDid You KnowAnon Mus100% (1)

- Movie Review Inside JobDocument7 pagesMovie Review Inside JobVikram Singh MeenaNo ratings yet

- The Aftershock Survival Summit TranscriptionDocument27 pagesThe Aftershock Survival Summit TranscriptionNicole SalvadorNo ratings yet

- The Great Global Debt PrisonDocument4 pagesThe Great Global Debt Prisonjas2maui100% (1)

- How Did It Go So Wrong - Goldman Asks, As It Slashes Oil Price TargetDocument5 pagesHow Did It Go So Wrong - Goldman Asks, As It Slashes Oil Price TargetnabsNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola's 20 Billion Dollar Brands & Future Growth14Document12 pagesCoca-Cola's 20 Billion Dollar Brands & Future Growth14nabsNo ratings yet

- Hudson's Bay Co. v.5.0 (September 6)Document68 pagesHudson's Bay Co. v.5.0 (September 6)nabsNo ratings yet

- From The Archives Warren Buffett 1977 Profile in The Wall Street JournalDocument4 pagesFrom The Archives Warren Buffett 1977 Profile in The Wall Street JournalnabsNo ratings yet

- Pabrai Investment Funds Annual Meeting Notes - 2014 - Bits - ) BusinessDocument8 pagesPabrai Investment Funds Annual Meeting Notes - 2014 - Bits - ) BusinessnabsNo ratings yet

- Investment Process - Arrogance Will Always Get The Best of You in Finance - The Talkative ManDocument4 pagesInvestment Process - Arrogance Will Always Get The Best of You in Finance - The Talkative MannabsNo ratings yet

- The Opportunity in Municipal Closed End Funds The Value in The 9th Inning of The Great Bond RallyDocument7 pagesThe Opportunity in Municipal Closed End Funds The Value in The 9th Inning of The Great Bond RallynabsNo ratings yet

- Family Making $200,000 A Year Is Feeling The Pinch in Pricey NWT - Financial PostDocument3 pagesFamily Making $200,000 A Year Is Feeling The Pinch in Pricey NWT - Financial PostnabsNo ratings yet

- Whitney Tilson On Tom Gayner Misbehaving BlackberryDocument6 pagesWhitney Tilson On Tom Gayner Misbehaving BlackberrynabsNo ratings yet

- Ray Dalio Part Two Bridgewater GrowsDocument4 pagesRay Dalio Part Two Bridgewater GrowsnabsNo ratings yet

- The Investor's Paradox Making Intelligent Decisions Amid More ChoicesDocument10 pagesThe Investor's Paradox Making Intelligent Decisions Amid More ChoicesnabsNo ratings yet

- Sallie Krawcheck Says Female Investors Ignored Points To OpportunityDocument3 pagesSallie Krawcheck Says Female Investors Ignored Points To OpportunitynabsNo ratings yet

- Belgium Passes Law Against - Vulture FundsDocument3 pagesBelgium Passes Law Against - Vulture FundsnabsNo ratings yet

- June 30, 2015: Investment Approach - Business, People, Price Fund ProfileDocument1 pageJune 30, 2015: Investment Approach - Business, People, Price Fund ProfilenabsNo ratings yet

- OFR - Financial Stability Risks Remain Moderate (CHARTS)Document11 pagesOFR - Financial Stability Risks Remain Moderate (CHARTS)nabsNo ratings yet

- Seth Klarman's Baupost Fund Semi-Annual Report 19991Document24 pagesSeth Klarman's Baupost Fund Semi-Annual Report 19991nabsNo ratings yet

- Walter Schloss Part Three The Magic of CompoundingDocument6 pagesWalter Schloss Part Three The Magic of CompoundingnabsNo ratings yet

- Century Partners 1970 Barron's Interview - Part TwoDocument4 pagesCentury Partners 1970 Barron's Interview - Part TwonabsNo ratings yet

- Net Long Short Net Long Short Exposure P&L YTD: June Exposure & Performance PerformanceDocument1 pageNet Long Short Net Long Short Exposure P&L YTD: June Exposure & Performance PerformancenabsNo ratings yet

- Skill Versus Luck and Investment PerformanceDocument5 pagesSkill Versus Luck and Investment PerformancenabsNo ratings yet

- Steve Romick SpeechDocument28 pagesSteve Romick SpeechCanadianValueNo ratings yet

- (Archives) Notes To James Grant's Spring Conference 2007Document7 pages(Archives) Notes To James Grant's Spring Conference 2007nabsNo ratings yet

- Bill Ackman Is Keeping On Buying Zoetis544Document6 pagesBill Ackman Is Keeping On Buying Zoetis544nabsNo ratings yet

- Top Hedge Fund Returns 45% With Robertson's 36-Year-Old Disciple - Bloomberg Business1Document8 pagesTop Hedge Fund Returns 45% With Robertson's 36-Year-Old Disciple - Bloomberg Business1nabsNo ratings yet

- 3 Attractive Stocks To Buy - at A Sizeable Discount - ForbesDocument5 pages3 Attractive Stocks To Buy - at A Sizeable Discount - ForbesnabsNo ratings yet

- DC Global Stock Fund Fact SheetDocument2 pagesDC Global Stock Fund Fact SheetnabsNo ratings yet

- Pershing Square European Investor Meeting PresentationDocument67 pagesPershing Square European Investor Meeting Presentationmarketfolly.com100% (1)

- Why It's Good To Be Young in Japan - WisdomTree ETF BlogDocument3 pagesWhy It's Good To Be Young in Japan - WisdomTree ETF BlognabsNo ratings yet

- Abdc Journal ListDocument192 pagesAbdc Journal ListRuwan Dileepa0% (1)

- Negotiable Instrument Law CasesDocument7 pagesNegotiable Instrument Law CasesAngelo Raphael B. DelmundoNo ratings yet

- Non-Performing Asset of Public and Private Sector Banks in India A Descriptive Study SUSHENDRA KUMAR MISRADocument5 pagesNon-Performing Asset of Public and Private Sector Banks in India A Descriptive Study SUSHENDRA KUMAR MISRAharshita khadayteNo ratings yet

- Core Banking SolutionDocument11 pagesCore Banking SolutionAwode TolulopeNo ratings yet

- Foreign Portfolio Investment in IndiaDocument27 pagesForeign Portfolio Investment in IndiaSiddharth ShindeNo ratings yet

- Discussion Activity Eco2 1Document2 pagesDiscussion Activity Eco2 1Marie Sheryl FernandezNo ratings yet

- ACCOUNTINGDocument408 pagesACCOUNTINGRafael Renz DayaoNo ratings yet

- SBI Priject Working Capital ManagementDocument58 pagesSBI Priject Working Capital Managementarijit242282% (76)

- Monetary Policy & Its ImpactDocument23 pagesMonetary Policy & Its ImpactHrishikesh DargeNo ratings yet

- People of The Phils. v. Gilbert Reyes Wagas, G.R. No. 157943, September 4, 2013Document3 pagesPeople of The Phils. v. Gilbert Reyes Wagas, G.R. No. 157943, September 4, 2013Lexa L. DotyalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Introduction of The Project: (A) UBLDocument6 pagesChapter 1: Introduction of The Project: (A) UBLRamzanNo ratings yet

- Common Transaction SlipDocument3 pagesCommon Transaction Slipabdriver2000No ratings yet

- Sahara Private PlacementDocument26 pagesSahara Private PlacementRahul MishraNo ratings yet

- ETS Study GuidesDocument170 pagesETS Study GuidessaketramaNo ratings yet

- Good Govenance A ND Social Responsi Bility: by Prof. Virnex Razo-Giamalon, MMDocument32 pagesGood Govenance A ND Social Responsi Bility: by Prof. Virnex Razo-Giamalon, MMSantiago BuladacoNo ratings yet

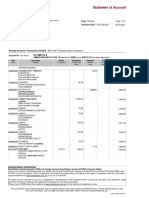

- Statement of Account: No 48L Lorong 5 Jalan Nong Chik Nong Chik Heights Johor Bahru 80100 JOHOR, JOHORDocument2 pagesStatement of Account: No 48L Lorong 5 Jalan Nong Chik Nong Chik Heights Johor Bahru 80100 JOHOR, JOHORFake PopcornNo ratings yet

- CH 10 - Information Technology Act, 2000Document29 pagesCH 10 - Information Technology Act, 2000Kinish ShahNo ratings yet

- Empanelment of Retired Officers of On Contract As Faculty at Staff Learning CenterDocument5 pagesEmpanelment of Retired Officers of On Contract As Faculty at Staff Learning CenterSiva SubrahmanyamNo ratings yet

- Central Bank Circular No. 905: General ProvisionsDocument6 pagesCentral Bank Circular No. 905: General ProvisionsRaezel Louise VelayoNo ratings yet

- No. L-33320. May 30, 1983. Ramon A. Gonzales, Petitioner, vs. The Philippine NATIONAL BANK, RespondentDocument10 pagesNo. L-33320. May 30, 1983. Ramon A. Gonzales, Petitioner, vs. The Philippine NATIONAL BANK, RespondentCatrinah Raye VillarinNo ratings yet

- Albert. Capitalism vs. Capitalism Ch. 1 and 6 PDFDocument26 pagesAlbert. Capitalism vs. Capitalism Ch. 1 and 6 PDFJesus JimenezNo ratings yet

- TD Bank Payment ContracDocument2 pagesTD Bank Payment Contracshafa anisa ramadhaniNo ratings yet

- Iraq Oil and Gas Final Tender Protocol - Round1Document67 pagesIraq Oil and Gas Final Tender Protocol - Round1Rexx Mexx100% (1)

- FI Group AssignmentDocument20 pagesFI Group AssignmentLilyNo ratings yet

- 4th ALCO PPT - v1.0Document56 pages4th ALCO PPT - v1.0vedantacharya1829No ratings yet

- Unit V National IncomeDocument21 pagesUnit V National IncomemohsinNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Good GovernanceDocument25 pagesThesis On Good GovernanceJoshua Eric Velasco DandalNo ratings yet

- Sole Proprietor DocumentsDocument3 pagesSole Proprietor DocumentsAmar Ali JunejoNo ratings yet

- Singhal Enterprises Private Limited RRDocument8 pagesSinghal Enterprises Private Limited RRRahulNo ratings yet

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpFrom EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeFrom EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (572)

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaFrom EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- The Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaFrom EverandThe Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesFrom EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNo ratings yet

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteFrom EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- The Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldFrom EverandThe Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesFrom EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo ratings yet

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismFrom EverandThe Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Camelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseFrom EverandCamelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismFrom EverandReading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismNo ratings yet

- Crimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963From EverandCrimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Power Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicFrom EverandPower Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaFrom EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943From EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordFrom EverandAn Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Confidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentFrom EverandConfidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (52)

- Socialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismFrom EverandSocialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorFrom EverandThe Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorNo ratings yet

- Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicFrom EverandTrumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (68)

- We've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityFrom EverandWe've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityNo ratings yet

- The Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American FutureFrom EverandThe Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American FutureRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (47)

- The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushFrom EverandThe Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaFrom EverandHatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- A Short History of the United States: From the Arrival of Native American Tribes to the Obama PresidencyFrom EverandA Short History of the United States: From the Arrival of Native American Tribes to the Obama PresidencyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (19)