Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Low Back Pain Incidence, Anthropometric Characteristics and

Uploaded by

Sri AgustinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Low Back Pain Incidence, Anthropometric Characteristics and

Uploaded by

Sri AgustinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

LOW BACK PAIN INCIDENCE, ANTHROPOMETRIC CHARACTERISTICS AND

ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING IN PREGNANT WOMEN IN A TEACHING HOSPITAL

CENTER ANTENATAL CLINIC

Adetoyeje Yoonus Oyeyemi,1,2 Adamu Ahmad Rufa'i,1 Aliyu Lawan1

1

Department of Medical Rehabilitation, College of Medical Sciences, University of Maiduguri.

Nigeria

2

Program in Physical Therapy, Dominican College of Blauvelt. Orangeburg, New York, USA

Aliyu Lawan, Department of Physiotherapy, College of Medical Sciences, University of Maiduguri,

Maiduguri, Nigeria.

ABSTRACT

Context: Although Low back pain (LBP) is a common problem during pregnancy, there is a death of

empirical data on its etiology and possible risk factors especially in African population.

Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between LBP, anthropometric

characteristics and Cumulative Index of Activities of Daily Living (CIADL) among pregnant women.

Study design: A cross sectional survey sample of pregnant women (N=310) attending the antenatal clinic of

University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital was conducted using a close ended questionnaire to elicit

information on socio-demographic characteristics, maternity record, activities of daily living functions

performed as home chores and LBP experience. Anthropometric measurement of height, weight, waist

circumference and hip circumference were also recorded.

Result: A simple majority of the participants (52.3%) had LBP with lumbar type being predominant

(55.1%). Majority of the pregnant women (55.6%) who experiences LBP were in their third trimester of

pregnancy and pregnant women with formal education (2=31.6, p=0.001) and civil servants (2=5.8,

p=0.03) tends to report LBP more than the others without education and of other occupation respectively.

Primigravid women tend to report LBP more frequently than the multigravid (2= 9.9, p=0.001) and parity

was tenuously but inversely associated with LBP (r= -0.18 p= 0.002). While body weight was tenuously

associated (r= 0.120 p= 0.035) with LBP, CIADL was not associated with LBP during pregnancy (r= -0.02,

p= 0.71).

Conclusion: The study affirms LBP as a common problem during pregnancy and this pain is unrelated to the

intensity of chores performed by the cohorts of pregnant women in their homes.

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is a period that is

characterized by hormonal, anatomical,

1

cardiovascular and pulmonary changes with

concomitant edema and weight gain which may

have possible effect on pregnant women's

balance and posture.2 Low Back Pain (LBP) is a

common problem during pregnancy3,4,5 and

majority of women report their first episode of

E-mail: aliyulawanladan@yahoo.com

29

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 29 (1), April 2012

6,7

LBP during pregnancy. This pain was

perceived to be severe enough to cause a

substantial proportion (19%) of American

women not to have another pregnancy due to

8

fear of LBP reoccurrence.

LBP is a condition of pain, aches,

stiffness or fatigue localized to lumbosacral

9

region of the spine . Pregnancy-related LBP has

been defined as any type of idiopathic pain

arising between the 12th rib and the glutei folds

during the course of the pregnancy, and which is

not attributed to a specific pathological

10

condition such as a disc herniation. It has been

suggested that pregnancy-related LBP is almost

a normal problem during the initial stage in

pregnancy and only becomes a cause for

concern when it persists as the pregnancy

11

advances.

There has been controversy as to

whether LBP is an essential component of a

healthy pregnancy. This controversy is not

deemed mitigated by a previous study that

found no correlation between LBP and the

5

health of a pregnancy. It has also been

suggested that LBP may play a protective role

by forcing them to be more cautious during

activities and safeguard them from accidents

12

d u r i n g p r e g n a n c y. N e v e r t h e l e s s ,

anthropometric parameters such as height,

weight and waist-hip ratio, and the type of job

and house chores the woman does, have been

identified as possible causes of LBP in

10

pregnancy.

Previous studies have reported strong

relationship between pregnancy LBP and

parity, whereas the relationship between LBP

and age, height, weight, race, fetal weight, and

socioeconomic status remains unclear due to

6,13,14,15

conflicting findings.

The type of ADL the

pregnant women engage in during pregnancy

causes different level of stress on their back and

the prevalence of LBP has been attributed to

specific type of work or activity engaged in

16

during pregnancy. Working in a constrained

posture; prolonged periods of standing, lifting,

twisting, bending forward; inability to take

7,14,17,18

breaks at will; and post-work fatigue

have

been suggested as causes of LBP in pregnant

women. Ironically in another study, women who

work for short time frequently experience severe

pain than those who worked for a prolonged

19

period.

Despite the abundance of literature on

LBP, etiology of pregnancy-related LBP

10,20

remains poorly understood and a review of

previous studies reveals many discrepancies in

21

epidemiological findings. For example, the

incidence of LBP during pregnancy ranges from

24% to 90% for different population samples in

both retrospective and prospective

13,14,22,23,24

studies

and there is no established fact or

20

consensus on its causes.

The extant literature shows that most

studies that explicitly describe LBP during

pregnancies were on different populations in the

25

developed countries. It is unclear whether there

is any relationship between incidence of LBP

and anthropometric characteristics including

weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, hip

circumference and waist-hip ratio among

pregnant women. Empirical data on the

relationship between incidence of LBP and

cumulative index of ADL, parity and number of

born children among pregnant women in a

Nigerian population is unavailable. The aim of

this study was to determine the relationship

between incidence of LBP, anthropometric

characteristics, pregnancy history and current

stage, type of gravida, and cumulative index of

activities of daily living (CIADL) in pregnant

30

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

women who attended antenatal clinic at the gestational age, parity status, number of children

University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital.

and history of previous delivery were obtained.

Section III consists of items that elicit

S U B J E C T S , M A T E R I A L S A N D information on ADL of the participants and in

section IV, information on the subjective report

METHODS

of LBP was obtained. Data on the

Subjects

A convenient sample of pregnant anthropometric characteristics of the

women who were attending the ante-natal clinic participants was recorded in section V.

From the response to section III items, the

of obstetrics and gynecology department of

University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital Cumulative Index of Activity of Daily Living

participated in this cross sectional survey study. (CIADL) was derived. CIADL is a product of the

Participants who have LBP due to other causes time spent (in minutes) per day in different ADL

such as trauma or with known co-existing and a weight factor correlated with estimated

27

medical disease such as malignant or systemic oxygen consumption for that ADL. Moderate

diseases were excluded. Using a Yaro Yamane activities such as cooking, sweeping and laundry

formula a minimum of 310 samples was has a weight factor of 4.0 and walking activities

has a factor of 3.3.28,29

determined to be adequate.26

MATERIALS

The participants completed a 38item

close ended structured questionnaire developed

from a previous study.27 Adaptations made to

the original instrument were adding questions

related to maternity record while activities that

were not applicable to the target population's

role in their milieu and environment such as

watering of flowers, were removed from the

questionnaire. The final questionnaire was

assessed by six physiotherapists each with 7-15

years of practice experience and all attested to

the face validity of the instrument. A test re-test

reliability of 0.73 was also obtained when tested

by 11 academic and clinical staff within a two

weeks interval.

Section I of the five part questionnaire

elicited information on the socio-demographic

characteristics of the participants such as age,

highest formal educational level attained,

occupation and marital status. In section II,

information from medical records including

METHODS

Following approval by the Institutional

Ethical Review Committee (IRC) of the

University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital,

participants were contacted on their clinic days

(Tuesdays and Thursdays) in the obstetrics and

gynecology department of the University of

Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. The purpose,

benefits and possible risk of the study were

explained to the participants, their informed

consent was obtained and the test instrument

(questionnaire) was distributed. Participants

who could not read were assisted by the

researcher in completing the questionnaire using

a Hausa or Kanuri language version of the

questionnaire. Upon completion, the

questionnaires were either collected on the same

day of distribution (n=187) or next appointment

date (n=123).

Upon submission of the questionnaire,

participants' weight, height, and waist and hip

circumference were measured. Height was

31

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

measured using a wooden height meter while

weight was measured using a weighing scale

(Hanna bathroom scale model, China. BNo:

29072184) while an inelastic tape rule (150cm

long. Butterfly brand, china) was used to

measure hip and waist circumference. WaistHip ratio of the participants was obtained by

dividing the waist circumference with the hip

circumference. Height and circumferential

measurements were recorded to the nearest

centimeter (cm), while weights were recorded

to the nearest 0.1 kg.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics of mean and

standard deviation were used to describe the

physical characteristics, sociodemographic

characteristics and pattern of ADL of the

participants. Spearman correlation coefficient

and chi square were used to determine the

relationship among variables including

sociodemographic, anthropometric

characteristics, data on maternity record

including parity, previous birth history and

number of children, CIADL and the incidence

of LBP among the pregnant women at a level of

0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics and Cumulative Activity of

Daily Living of the Participants

The mean age, body mass index and

waist circumference of participants was 25.61 +

5.02 years 25.92 + 5.37 kg/m2 and 96.62 + 11.36

cm respectively, while their mean hip

circumference, mean waist-hip ratio and the

mean CIADL were 100.93 + 11.56 cm, 0.96 +

0.10 and 1093.70 + 647.05 MET-min/day

respectively. All the participants were married,

more than half were full time housewives

(53.5%, n=166), 37.1% (n=115) had a higher

level of formal education and an overwhelming

majority (91.4%, n=192) had a previous history

of normal virginal delivery.

Almost all the pregnant women in the

present study cook (98%, n=304) while more

than half of them were full time house wife.

Majority of the participants (54.5%, n=169)

cook, sweep and do laundry, only 8.4% (n=26)

cook and sweep while very few (1.9%, n=6)

engage in only sweeping in the house. A

substantial number of the participants (35.2%,

n=109) walk for less than 15 min in a day, and

23.9% (n=74) walk for more than an hour a day

(Table 1).

Incidence and Pattern of LBP

A simple majority of the participants

(52.3%, n=162) had LBP out of which 85.8%

(n=139) reported pain onset during pregnancy.

Only 10 (6.2%) of the pregnant women with

LBP were in their first trimester, 62 (38.3%) of

them were in their second trimester and 90

(55.6%) were in their third trimester. Also, the

pain was reported to be aggravated by activities

by 60.6% (n=97) of the pregnant women, while

rest and other things aggravated the pain in 30%

(n=48) and 9.4% (n=15) of the women

respectively. LBP was reported to be relieved by

rest by 72.8% of the women, whereas activities

and others measures relieve the pain in 19.1%

(n=31) and 8% (n=13) of them respectively.

Seventy nine (49.4%) pregnant women

who reported LBP during pregnancies

experienced pain in the night, 37.5% (n=60)

reported pain experience during the day, while

13.1% (n=21) of the pregnant women felt pain in

the morning. The pain experienced was reported

to last for some seconds, minutes or up to some

hours by only three (1.9%), 97 (60.6%) and 60

(37.5%) participants respectively. LBP was said

32

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

to be mild and moderate by two and eight

women respectively in their first trimester of

pregnancy and none of the women in the first

trimester reported severe pain. However the

highest incidence of severe LBP was reported

by women in the second trimester of pregnancy

(n=25) and the highest incidence of moderate

LBP was by women in the third trimester of

their pregnancy (n=53).

Eighty nine (55.1%) women with LBP

reported having the pain at lumbar region and

73 (44.9%) at sacro-iliac region. Many (42.9%,

n=69) of these pregnant women described the

pain as throbbing, some described it as aching

(14.9%, n=24), shooting (13.7%, n=22) or

stabbing (28.6%, n=46). Ninety one (56.2%)

pregnant women with LBP reported no

radiation of the pain while 33.3% (n=54)

reported radiation onto the thigh and 10.5%

(n=17) reported radiation down to the calf

muscles (Table 2).

pregnant women who reported pain in the

second and third trimester (2=11.0, p=0.04).

Pregnant women with LBP who are carrying

their first babies tend to report LBP more

frequently when compared to those who had

carried one or more pregnancies before (r= -0.18

p= 0.002).

Table 1: Characteristics and Activities of the Participants

Characteristics

Occupation

Characteristics

House help

Civil Servant

70

22.6

Yes

107

34.6

Business

19

6.1

No

202

65.4

House Wife

166

53.5

Student

55

17.7

Nil

80

25.8

Cooking

70

22.6

Primary

13

4.2

Sweeping

1.9

Secondary

102

32.9

Laundry

Tertiary

115

37.1

Cooking/Sweeping 26

8.4

Cooking/L aundry

11.6

Formal Education

Activities of Daily Living

Gestational Age

1st trimester

36

20

6.5

Laundry/Sweeping 3

1.0

2 trimester

118

38.1

Cook/Swep/Laund. 169

54.5

3rd trimester

172

55.5

Nulliparous

98

31.6

< 1 hour

133

43.0

Multiparous

212

68.4

1-2 hours

113

36.6

63

20.4

nd

Parity

Time spent working

History of Previous Delivery

2-3 hours

Virginal del ivery

192

91.4

Caesarean section

18

8.6

Duration of walking

<15 minutes

109

35.2

<3

122

57.8

Up to 30 minutes

127

41.0

>4

89

42.2

> I hour

74

23.9

Number of Children

Housewife = full time ho usewife ; Cook/Swep/L aund. = Cooking/Seeping/Laundry

Table 2: Incidence and Pattern of Low back pain among pregnant women

Differences by Demographic characteristics

Low back pain tend to be frequent

among those with formal education compared

to those without education (2=31.6, p<0.001),

and also tend to occur among women with

primigravid compared to those with

multigravid pregnancies (2=9.8, p<0.001).

Civil servants tends to report LBP more than

pregnant women of other occupations (2=5.8,

p=0.03). Pregnant women in their third

trimester tend to report LBP than those in the

second or first trimesters of their pregnancies

(2=26.7, p<0.001). Pregnant women in the

second trimesters who reported LBP tend to

have their pain relieved by rest than those in

other trimesters (2 =26.7, p=0.003). LBP in

pregnant women in their first trimesters tend not

to radiate to other body parts compared to

Characteristics

LBP

Yes

162

52.3

No

148

47.7

Before pregnancy

23

14.2

During Pregnancy

139

85.8

Lumbar region

89

55.1

Sacro-iliac region

73

44.9

Rest

48

30

Activities

97

60.6

Others

15

9.4

Rest

118

72.8

Activities

31

9.1

Others

13

Aching

24

14.9

Throbbing

69

42.9

Shooting

22

13.7

Stabbing

46

28.6

Mild

23

14.1

Moderate

93

57.1

Severe

47

28.8

No radiation

91

56.2

Radiate within the thigh

54

33.3

Radiate down the calf

17

10.5

LBP Occurrence

Location of the pain

Aggravating factor

Relieving factor

Characteristics of the Pain

Grade of the pain

Pattern of Radiation

Others in the relieving factors for the LBP include use of medication etc.

33

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

DISCUSSION

Almost the entire participant in the

present study cook (98%, n=304) and more than

half of them were full time house wife. This is

an indication that household chores and

especially cooking remain a gender specific

role assigned to the cohorts of women in this

study. It affirm that women staying home to

raise children and not going out to work is a

common practice in this part of the world.

Prevalence and characteristics of LBP

More than half of the pregnant women in

the present study reported they had LBP during

pregnancy, affirming the high prevalence of

LBP (52.3%). This finding is comparable to

49% reported in a study by Berg et al14, 51% in

that of Sturesson et al12 and 52.5% in that of

Ayanniyi et al.25 A priori, with about 14.2% of

the women reporting LBP experience that

started before conception, it appears more

pregnancy related LBP exists in the pregnant

women in the present study compared to other

studies in which 20-25% of pregnant women

have LBP that predates their pregnancies. 12, 30

The present study shows a steep increase

in the frequency of LBP among pregnant

women in the second trimester of pregnancy

compared to those in the first trimester and a

modest increase in their third trimester

compared to second trimester. On average, 56%

increase in LBP incidence was noted among

those in the third trimester compared to those in

the first trimester. The steep increase in the

frequency of LBP with advancing gestational

period observed in the present study is at

variance with that of Ostgaard and Anderson30

who found LBP among pregnant women to

increase by about 25% among women in their

third trimester compared to those in the first

trimester.

Pain intensity during pregnancy appears

to fluctuate, with majority of the participants

reporting worst pain at night. Majority (57.1%)

of the pregnant women graded their pain as

moderate, similar to findings in a previous

study.31,32 Our finding of higher frequency of

lumber type of LBP compared to the sacroiliac

type is in agreement with Ayanniyi et al25 but at

variance with that of Collinton.21 This high

frequency of lumbar LBP observed was more

among primigravid participants compared to

their multigravid counterparts who tends to

report more sacroiliac LBP. The differences

observed with this regard have been explained

by a multi factorial interplay of hormonal

sensitivity differences and previous antenatal

experiences.33

Relationship between LBP Incidence,

Anthropometric Characteristics and CIADL

Results from the present study showed

that the weight of the pregnant women was

tenuously but significantly related to LBP

during pregnancy. This finding is at variance

with those of others that disputed any

relationship between weight and LBP during

pregnancy. 4,5,21 Divergence between our findings

and those of others may be explained by

differences in methodology, and the possible

differences in the physical characteristics of the

subjects in the present study and others. Finding

in the present study is however expected when

viewed against the increase in weight

experienced by the pregnant women attributable

to fluid retention and weight of the fetus.10 On the

other hand, absence of any relationship between

height, BMI, waist and hip circumference,

waist-hip ratio and LBP, observed in the present

study is consistent with the findings of previous

34

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

studies that found no association between

anthropometric characteristics and LBP during

pregnancy.13, 34

Our study shows an increased severity

and frequency of LBP among women in their

forth to sixth months of pregnancies

corresponding fairly to the time of rapid weight

gain which has been determined to be between

the fifth and sixth months of pregnancy.35 Based

on our findings, parallelism can be drawn

between the time of increased frequency of LBP

and pain severity among pregnant women in the

present study, and the short time frame in which

the mother's weight increases during pregnancy

in an earlier study.34

Though in the present study, a large

proportion (60.6%) of the participants reported

that excessive house hold work (ADL)

aggravated their LBP during pregnancies, no

significant relationship between LBP and

CIADL among pregnant women was observed.

While this finding in the present study is in line

with the results from Yip et al,25 it is indirectly at

variance with a previous report16 that implicated

high incidence of LBP among women that work

throughout their pregnancy. Absence of any

relationship between CIADL and LBP among

the pregnant women in the present study

indirectly affirms that physical activities and

prescribed exercise has no adverse effect on

symptoms during pregnancy. However unlike

in a previous study in which vocational factors

such as constrained work posture; prolonged

periods of standing, lifting and twisting was

found to be contributory to LBP,14,18 our study

assessed CIADLs rather than these other

occupational factors.

The previous studies that either disputed

weight as contributory to LBP during

pregnancy, attributed high ADL to LBP during

pregnancy or report high incidence of sacro iliac

LBP were conducted in other parts of the

world.4,5,21 Findings of the present study is at

variance with those previous reports but are

consistent with that of Ayanniyi et al;25 a study

on a Nigerian population. Differences between

our findings and those of others could be

attributable to differences in the physical

characteristics between our study populations

and those of the other studies.

Limitation of the study

One limitation of the present study is the

self-reported nature of some items on the

questionnaire. Therefore, the reliability of the

information obtained may not be ascertained as

the history of LBP was self reported. Although

the overall sample size in the present study may

be considered reasonable and is comparable to

those of previous studies12,27 however, given that

close to half of the pregnant women sampled in

the present study reported LBP, some absolute

but insignificant differences by subgroups of

women with LBP may still be attributable to type

II error.

CONCLUSION

Our study found that majority of pregnant

women who attend antenatal clinic in a major

regional teaching hospital center in Nigeria

present with LBP. The results revealed that

body weight of the pregnant women is

tenuously associated with LBP, parity was

tenuously but negatively associated with LBP,

while performing high or low level intensity

ADL at home was not associated with LBP in

the cohort of pregnant women. Future large

scale studies on the relationship between

absolute and relative weight gain and LBP

during pregnancy may elucidate the effect of

35

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

body weight on the incidence of LBP in the

population of North Eastern Nigeria. The

effect of general work, working posture, and

psychological effect of the work and LBP in

pregnancies may also be explored.

a rural community in southwest Nig. Afr J

Med Med sci, 2005; 34(3):259-262.

10. Darryl B, Sneag AB, John A, Bendo MD.

pregnancy related low back pain.

Orthopedics, 2007; 30(10):839.

11. Victoria A. Lower back pain during

pregnancy. Dynamic Chiropractice, 1994;

12:15.

12. Sturesson B, Uden G, Uden A. Pain pattern

in pregnancy and catching of the leg in

pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain.

Spine, 1997; 22:1880-1883.

13. Mantle MJ, Greenwood RM, Currey HL.

Backache in pregnancy. Rheumatol Rehabil,

1997; 16:95-101.

14. Berg G, Hammar M, Moller-Nielsen J,

Linden U, Thorblad J. Low back pain during

pregnancy. Obstetric and Gynecol. 1988;

71:71-75.

15. Fast A, Weiss L, Ducommun EJ. Low-back

pain in pregnancy: abdominal muscles, situp performance and back pain. Spine, 1990;

15(1):28-30

16. Ostgaard HC. Assessment and treatment of

low back pain in working pregnant women.

Semin Perinatol, 1996; 20:61-69.

17. Paul, J.A., Dijk, F.J. and Frings-Dresen,

M.H.(1994): Work load and musculoskeletal

complaints during pregnancy. Scand J Work

Environ Health. 1994; 20:153-159.

18. Endresen EH. Pelvic pain and low back pain

in pregnant women--an epidemiological

study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995; 24:135141.

19. Frymoyer JW, Pope MH, Clements JH,

Wilder DG, MacPherson B, Ashikaga T.

Risk factors in low-back pain. An

epidemiological survey. J Bone Joint Surg

Am. 1983; 65:213-218.

REFERENCE

1. Ritchie JR. Orthopedic considerations

during pregnancy. Clinic Obstet Gynecol.

2003; 46(2):456-66.

2. Heckman JD, Sassard R. Musculoskeletal

considerations in pregnancy. J Bone Joint

Surg Am, 1994; 76(11):1720-30.

3. Foti T, Davids JR, Bagley A. A

biomechanical analysis of gait during

pregnancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;

82:62532.

4. Noren L, Ostgaard S, Nielsen TF, Ostgaard

HC. Reduction of sick leave for lumbar

back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy.

Spine. 1997; 22:215760.

5. Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB, Wennergren,

M. The impact of low back and pelvic pain

in pregnancy on the pregnancy outcome.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1991; 70:2124.

6. Svensson HO, Andersson GB, Hagstad A,

Jansson PO. The relationship of low-back

pain to pregnancy and gynecologic factors.

Spine. 1990; 15:371-375.

7. Orvieto R, Achiron A, Ben-Rafael Z,

Gelernter I, Achiron R. Low-back pain of

pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.

1994; 73:209-214.

8. Brynhildsen J, Hansson A, Persson A,

Hammar M. Follow-up of patients with low

back pain during pregnancy. Obstet and

Gynecol. 1998; 91:182-186.

9. Fabunmi A, Aba S, Odunaiya N. Prevalence

of Low back pain among paesant farmers in

36

Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 30 (1), April 2013

20. Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM,

Van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI. Pregnancyrelated pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I:

Terminology, clinical presentation, and

prevalence. Pain. 2004; 35: 76-83

21. Colliton, J. (1996). Back pain and

Pregnancy: Active management strategies.

Phys Sports Med. 1996; 24(7): 89 - 93.

22. Nwuga VC. Pregnancy and back pain

among upper class Nigerian women. Aust J

Physiother. 1992; 28:8-11.

23. Kristiansson P, Svardsudd K, von Schoultz

B. Back pain during pregnancy: a

prospective study. Spine. 1996; 21:702-709.

24. Wergeland E, Strand K. Work pace control

and pregnancy health in a population-based

sample of employed women in Norway.

Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;

24:206-212.

25. Ayanniyi O, Sanya AO, Ogunlade SO, OniOrisan MO. (2006): Prevalence and pattern

of low back pain among pregnant Women

attending Ante-natal clinic in selected

health care facilities. Afr J Biomed

Research. 2006; 9: 149-156

26. Okeke AO. Foundation Statistics for

Business Decisions. Enugu: High mega

system limited. 1995; 25

27. Yip YB, Ho SC, Chan SG. Tall stature,

overweight and the prevalence of low back

pain in Chinese middle-aged women. Int J

Obesity. 2001; 25(6): 887-892.

28. Savage P, Ades P. A re-examination of the

metabolic equivalent (MET) concept in

individuals with coronary heart disease. J

Cardiopulmonary Rehab Prevention. 2007;

27(5):321 321

29. Byrne N. et al. Metabolic equivalent: one

size does not fit all. J Appl Physiol. 2005; 99:

1112-1119

30. Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB. Previous back

pain and risk of developing back pain in a

future pregnancy. Spine. 1991; 16:432-436.

31. Fast A, Weiss L, Parikh S, Hertz G. Night

backache in pregnancy. Hypothetical

pathophysiological mechanisms. Am J Phys

Med Rehabil. 1989; 68:227-229

32. Ansari NN, Hasson S, Naghdi S, Keyhani S,

Jalaie S. Low back pain during pregnancy in

Iranian women: Prevalence and risk factors.

Physiother Theory Pract. 2010; 26(1):40-8

33. Hyatt MA, Keisler HD, Budge H, Symond

ME. Maternal parity and its effect on adipose

tissue deposition and endocrine sensitivity in

the postnatal sheep. J endocrinol. 2010;

204(2): 173-179

34. Fast A, Shapiro D, Ducommun EJ,

Friedmann LW, Bouklas T, Floman, Y. Lowback pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1987; 12:368371.

35. MacEvilly M, Buggy D. Back pain and

pregnancy: a review. Pain. 1996; 64:405414.

37

You might also like

- Yemisi Chapter ThreeDocument10 pagesYemisi Chapter ThreeAbimbola OyarinuNo ratings yet

- Sudha Salhan - Textbook of GynecologyDocument697 pagesSudha Salhan - Textbook of GynecologyCristinaCapros100% (1)

- FAST ExamDocument123 pagesFAST ExamSinisa Ristic50% (2)

- Pregnancy TestDocument10 pagesPregnancy TestquerokeropiNo ratings yet

- (Conceive) Garbhadhaana-Understanding Art of Conceiving Through Vedic AstrologyDocument4 pages(Conceive) Garbhadhaana-Understanding Art of Conceiving Through Vedic AstrologynitkolNo ratings yet

- General Surgery Tubes and DrainsDocument4 pagesGeneral Surgery Tubes and DrainsLorenzoVasquezDatul100% (3)

- Laryngeal Cancer: Anh Q. Truong MS-4 University of Washington, SOMDocument33 pagesLaryngeal Cancer: Anh Q. Truong MS-4 University of Washington, SOMSri Agustina0% (1)

- Pediatric Endocrinology Review MCQsDocument104 pagesPediatric Endocrinology Review MCQsTirou100% (1)

- Ectopic Pregnancy William 24thDocument44 pagesEctopic Pregnancy William 24th林昌恩No ratings yet

- Giovanni Maciocia Menorrhagia NotesDocument22 pagesGiovanni Maciocia Menorrhagia Noteshihi12100% (5)

- His Perfect Wife Susanne MccarthyDocument113 pagesHis Perfect Wife Susanne Mccarthymenaal5489% (38)

- M. Rizki Feiszal - 1706252Document9 pagesM. Rizki Feiszal - 1706252Rizqi ImdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Pregnancy-Related Lumbopelvic Pain: Listening To Australian WomenDocument11 pagesResearch Article: Pregnancy-Related Lumbopelvic Pain: Listening To Australian WomenKinesiologa Roxanna Villar ParraguezNo ratings yet

- Low Back Pain During Pregnancy Prevalence, Risk Factors and Association With Daily Activities Among Pregnant Women in Urban Blantyre, MalawiDocument6 pagesLow Back Pain During Pregnancy Prevalence, Risk Factors and Association With Daily Activities Among Pregnant Women in Urban Blantyre, MalawiAdrilia AnissaNo ratings yet

- Exercise in Pregnant Women and Birth WeightDocument4 pagesExercise in Pregnant Women and Birth WeightJelita SihombingNo ratings yet

- Predictive Factors For Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women: A Unvariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression AnalysisDocument5 pagesPredictive Factors For Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women: A Unvariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression AnalysisTiti Afrida SariNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Gestational Weight Gain A Cross Sectional SurveyDocument11 pagesFactors Associated With Gestational Weight Gain A Cross Sectional SurveyJosé Zaim Delgado RamírezNo ratings yet

- 6 UN Reddy EtalDocument6 pages6 UN Reddy EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Patient Attitudes Toward Gestational Weight Gain and ExerciseDocument9 pagesPatient Attitudes Toward Gestational Weight Gain and ExercisealexNo ratings yet

- BMJ f6398Document13 pagesBMJ f6398Luis Gerardo Pérez CastroNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Weight GainDocument9 pagesPregnancy Weight GainKevin MulyaNo ratings yet

- Chiropractic Care For Adults With Pregnancy Related Low Back, Pelvic Gridle Pain or Combinated Pais A Sistematic ReviewDocument18 pagesChiropractic Care For Adults With Pregnancy Related Low Back, Pelvic Gridle Pain or Combinated Pais A Sistematic ReviewQuiropraxia ChapecóNo ratings yet

- Back Pain During Pregnancy and Quality of Life of Pregnant Women (CROSS-SECTIONAL)Document10 pagesBack Pain During Pregnancy and Quality of Life of Pregnant Women (CROSS-SECTIONAL)Rohon EzekielNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research PaperDocument24 pagesNursing Research Paperapi-455624162No ratings yet

- Effects of Physical Activity During Pregnancy On Neonatal Birth WeightDocument8 pagesEffects of Physical Activity During Pregnancy On Neonatal Birth WeightRitmaNo ratings yet

- Preconception Care ofDocument11 pagesPreconception Care ofsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Obesity in PregnancyDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Obesity in Pregnancyafmzbdjmjocdtm100% (1)

- Obesity and PregnancyDocument6 pagesObesity and PregnancyBudiarto BaskoroNo ratings yet

- Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Obesity and The Risk of Shoulder Dystocia: A Meta-AnalysisDocument29 pagesMaternal Pre-Pregnancy Obesity and The Risk of Shoulder Dystocia: A Meta-Analysisaulia ilmaNo ratings yet

- Tugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandaniDocument23 pagesTugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandanianisFitrihandani anisaNo ratings yet

- 192 2013 Article 2061Document12 pages192 2013 Article 2061siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Associations of Snoring Frequency and Intensity in Pregnancy With Time-To - DeliveryDocument8 pagesAssociations of Snoring Frequency and Intensity in Pregnancy With Time-To - Delivery杨钦杰No ratings yet

- 08 AimukhametovaDocument10 pages08 AimukhametovahendraNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Exercise Overweight MetaanalysisDocument11 pagesPregnancy Exercise Overweight MetaanalysisAisleenHNo ratings yet

- Fetal Growth Velocity in Diabetics and The Risk For Shoulder Dystocia: A Case-Control StudyDocument6 pagesFetal Growth Velocity in Diabetics and The Risk For Shoulder Dystocia: A Case-Control Studyaulia ilmaNo ratings yet

- Muest RaDocument13 pagesMuest RaBruno LinoNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument6 pages1 PBShelamita ImanisaNo ratings yet

- Katherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1Document4 pagesKatherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1angelie21No ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument18 pagesResearch Paperapi-545542584No ratings yet

- Metgud Factors Affecting Birth Weight of A Newborn - A Community Based Study in Rural Karnataka, IndiaDocument4 pagesMetgud Factors Affecting Birth Weight of A Newborn - A Community Based Study in Rural Karnataka, IndiajanetNo ratings yet

- Maternal Anthropometry and Low Birth Weight: A Review: G. Devaki and R. ShobhaDocument6 pagesMaternal Anthropometry and Low Birth Weight: A Review: G. Devaki and R. ShobhaJihan PolpokeNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 09 00221 v2Document11 pagesNutrients 09 00221 v2Firman FajriNo ratings yet

- Stress Urinary Incontinence in Relation To Pelvic Floor Muscle StrengthDocument10 pagesStress Urinary Incontinence in Relation To Pelvic Floor Muscle StrengthNoraNo ratings yet

- Body Mass Index at Age 18 - 20 and Later Risk of Spontaneous Abortion in The Health Examinees Study (HEXA)Document8 pagesBody Mass Index at Age 18 - 20 and Later Risk of Spontaneous Abortion in The Health Examinees Study (HEXA)Faradiba NoviandiniNo ratings yet

- Stir Rat 2014Document1 pageStir Rat 2014Dayana Cuyuche JuarezNo ratings yet

- Effect of Exercise On Pregnancy OutcomeDocument14 pagesEffect of Exercise On Pregnancy OutcomeAisleenHNo ratings yet

- Dietary Inflammatory Potential and Risk of Breast Cancer A Population Based Case Control Study in France Cecile StudyDocument25 pagesDietary Inflammatory Potential and Risk of Breast Cancer A Population Based Case Control Study in France Cecile Studymaria.panevayahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 10493 v2Document11 pagesIjerph 18 10493 v2Dennize Rebb TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019Document1 pageMaternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019heidi leeNo ratings yet

- Article in Press: Effects of Central Obesity On Maternal Complications in Korean Women of Reproductive AgeDocument8 pagesArticle in Press: Effects of Central Obesity On Maternal Complications in Korean Women of Reproductive AgeMhmmd FasyaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Nursing Science - Benha University: JnsbuDocument15 pagesJournal of Nursing Science - Benha University: JnsbuBADLISHAH BIN MURAD MoeNo ratings yet

- R. Irvian1Document5 pagesR. Irvian1Ermawati RohanaNo ratings yet

- To Assess The Effect of Planned Teaching in Relation To Selected Aspect of Pih Among Antenatal Mothers - September - 2020 - 0036319316 - 0210196Document3 pagesTo Assess The Effect of Planned Teaching in Relation To Selected Aspect of Pih Among Antenatal Mothers - September - 2020 - 0036319316 - 0210196Vaibhav JainNo ratings yet

- Baby Carrying Method Impacts Caregiver Postural.2Document7 pagesBaby Carrying Method Impacts Caregiver Postural.2Cata Gomez UbillaNo ratings yet

- Abed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+-+LiDocument8 pagesAbed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+-+LiLydia LuciusNo ratings yet

- Maternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesMaternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleKristine Joy DivinoNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument6 pagesDownloadKai GgNo ratings yet

- None 2Document5 pagesNone 2Sy Yessy ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Aogs 101 1364Document10 pagesAogs 101 1364Aina SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Imc y FertilidadDocument9 pagesImc y FertilidadRichard PrascaNo ratings yet

- JBR 26 04 235Document6 pagesJBR 26 04 235Khuriyatun NadhifahNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Some Anthropometric IndicesDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Some Anthropometric IndicesMuhammad Al-TohamyNo ratings yet

- EN Nutritional Status and Quality of Life IDocument4 pagesEN Nutritional Status and Quality of Life IVera El Sammah SiagianNo ratings yet

- Effect of Antenatal Dietary Interventions in Maternal Obesity On Pregnancy Weight Gain and Birthweight Healthy Mums and Babies (HUMBA) Randomized TrialDocument13 pagesEffect of Antenatal Dietary Interventions in Maternal Obesity On Pregnancy Weight Gain and Birthweight Healthy Mums and Babies (HUMBA) Randomized TrialAripin Ari AripinNo ratings yet

- Original Communication: Diet During Pregnancy in Relation To Maternal Weight Gain and Birth SizeDocument8 pagesOriginal Communication: Diet During Pregnancy in Relation To Maternal Weight Gain and Birth SizeWulan CerankNo ratings yet

- Gestational Weight GainDocument3 pagesGestational Weight GainainindyaNo ratings yet

- Ijwh 5 501Document7 pagesIjwh 5 501MarianaafiatiNo ratings yet

- The Neglected Sociobehavioral Risk Factors of Low Birth WeightDocument7 pagesThe Neglected Sociobehavioral Risk Factors of Low Birth WeightBunda BiyyuNo ratings yet

- ANESTHESIOLOGY (R) 2016 - Refresher Course Lecture Summaries副本(被拖移)Document9 pagesANESTHESIOLOGY (R) 2016 - Refresher Course Lecture Summaries副本(被拖移)Han biaoNo ratings yet

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientFrom EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNo ratings yet

- Acute Histologic Chorioamnionitis at Term: Nearly Always NoninfectiousDocument7 pagesAcute Histologic Chorioamnionitis at Term: Nearly Always NoninfectiousSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Algoritma ARDSDocument7 pagesAlgoritma ARDSSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Chorioamnionitis and Neonatal Outcome: Early Vs Late Preterm InfantsDocument2 pagesChorioamnionitis and Neonatal Outcome: Early Vs Late Preterm InfantsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Safety and Efficacy of Levofloxacin Versus Rifampicin in Tuberculous Meningitis: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesSafety and Efficacy of Levofloxacin Versus Rifampicin in Tuberculous Meningitis: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled TrialSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Acute Histologic Chorioamnionitis at Term: Nearly Always NoninfectiousDocument7 pagesAcute Histologic Chorioamnionitis at Term: Nearly Always NoninfectiousSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Hosts UmbrellaDocument1 pageHosts UmbrellaFabsor SoralNo ratings yet

- Co Existence OfposttraumaticempyemaDocument5 pagesCo Existence OfposttraumaticempyemaSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Common Conjunctival LesionsDocument4 pagesCommon Conjunctival LesionsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Holzman 786 94Document9 pagesAm. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Holzman 786 94Sri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Outcome of Pediatric Empyema Thoracis Managed by Tube ThoracostomyDocument4 pagesOutcome of Pediatric Empyema Thoracis Managed by Tube ThoracostomySri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Suspected Tuberculous Empyema ThoracisDocument3 pagesBilateral Suspected Tuberculous Empyema ThoracisMuhammad Bilal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Chorioamnionitis and Neonatal Outcome: Early Vs Late Preterm InfantsDocument2 pagesChorioamnionitis and Neonatal Outcome: Early Vs Late Preterm InfantsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Current Surgical Treatment of Thoracic Empyema in AdultsDocument9 pagesCurrent Surgical Treatment of Thoracic Empyema in AdultsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Haemoperitoneum - Secondary Abdominal PregnancyDocument3 pagesAn Unusual Haemoperitoneum - Secondary Abdominal PregnancySri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Suspected Tuberculous Empyema ThoracisDocument3 pagesBilateral Suspected Tuberculous Empyema ThoracisMuhammad Bilal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Successful Salvage Therapy With Micafungin For Candida Emphyema Thoracis PDFDocument2 pagesSuccessful Salvage Therapy With Micafungin For Candida Emphyema Thoracis PDFSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Secondary Abdominal Pregnancy and Its Associated Diagnostic and Operative DileemmaDocument5 pagesSecondary Abdominal Pregnancy and Its Associated Diagnostic and Operative DileemmaSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Superimposed PebDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Superimposed PebSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- DICDocument3 pagesDICFarida AgustiningrumNo ratings yet

- A Live Intra Abdominal PregnancyDocument3 pagesA Live Intra Abdominal PregnancySri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Analisis Faktor Resiko Kehamilan Ektopik Di Rsud Dr.Document1 pageAnalisis Faktor Resiko Kehamilan Ektopik Di Rsud Dr.Sri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Term Abdominal Pregnancy With Healthy NewbornDocument3 pagesTerm Abdominal Pregnancy With Healthy NewbornSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- 501 1001 1 PB PDFDocument8 pages501 1001 1 PB PDFSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Genogram Pasien Home VisitDocument1 pageGenogram Pasien Home VisitSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- TCCSDocument8 pagesTCCSSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- The Social Determinants of Schizophrenia: An African Journey in Social EpidemiologyDocument18 pagesThe Social Determinants of Schizophrenia: An African Journey in Social EpidemiologySri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- OsteomylitisDocument11 pagesOsteomylitisSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Family Therapy For Schizophrenia in The South African Context Challenges and Pathways To ImplementationDocument8 pagesFamily Therapy For Schizophrenia in The South African Context Challenges and Pathways To ImplementationSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Bechtel Resume 2021Document1 pageBechtel Resume 2021api-468018392No ratings yet

- Munich Declaration, 2000Document4 pagesMunich Declaration, 2000Ilenuta Zanfir AglitoiuNo ratings yet

- Brochure - 26th World Congress On Pediatrics, Neonatology & Primary CareDocument6 pagesBrochure - 26th World Congress On Pediatrics, Neonatology & Primary CareSpandana RoyNo ratings yet

- Government College of Nursing:, Jodhpur (Raj.)Document6 pagesGovernment College of Nursing:, Jodhpur (Raj.)priyankaNo ratings yet

- Common Probe FailuresDocument18 pagesCommon Probe FailuresEuris Otilio Dominguez AmadisNo ratings yet

- Peripheral IntravenousDocument12 pagesPeripheral IntravenousDewi List0% (1)

- English Quiz for-WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesEnglish Quiz for-WPS OfficeIyaaNo ratings yet

- Morton's Metatarsalgia - Pathogenesis, Aetiology and Current ManagementDocument10 pagesMorton's Metatarsalgia - Pathogenesis, Aetiology and Current ManagementLikhit NayakNo ratings yet

- DeLancey AUGS Pres 2008Document129 pagesDeLancey AUGS Pres 2008blackanddeckerjoeNo ratings yet

- TFN Final ExamDocument2 pagesTFN Final ExamJamoi Ray VedastoNo ratings yet

- Askep DislokasiDocument19 pagesAskep DislokasiHana Syifana RobbyaniNo ratings yet

- Common Finger Sprains and Deformities PDFDocument19 pagesCommon Finger Sprains and Deformities PDFOmar Najera de GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Scale Down of Services Port Moresby General Hospital 17 Jul 2020Document2 pagesScale Down of Services Port Moresby General Hospital 17 Jul 2020csgo mainNo ratings yet

- Dental ProformaDocument2 pagesDental ProformaEhsin AliNo ratings yet

- Flyer SugiesDocument2 pagesFlyer SugiesInomy ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Medical Terms (Prefixes Suffixes Roots)Document5 pagesMedical Terms (Prefixes Suffixes Roots)David Donovan ManuelNo ratings yet

- Femoral Hernia RepairDocument17 pagesFemoral Hernia RepairIhsan AndanNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Refractive Amblyopia Treatment Study: ATS7 Protocol 5-24-04Document15 pagesBilateral Refractive Amblyopia Treatment Study: ATS7 Protocol 5-24-04samchu21No ratings yet

- Pederson PDFDocument5 pagesPederson PDFCosmina EnescuNo ratings yet

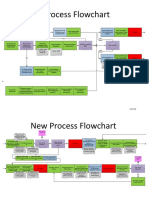

- New Process Flowchart CPOEDocument4 pagesNew Process Flowchart CPOELiza GeorgeNo ratings yet