Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 014521349400115B Main

Uploaded by

Cesc GoGaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 014521349400115B Main

Uploaded by

Cesc GoGaCopyright:

Available Formats

Pergamon

Child Abuse& Neglect,Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 177-189, 1995

Copyright 1995Elsevier ScienceLtd

Printed in the USA.All rights reserved

0145-2134/95 $9.50 + .00

0145-2134(94)00115-4

COMPARATIVE P S Y C H O P A T H O L O G Y OF WOMEN

WHO EXPERIENCED INTRA-FAMILIAL VERSUS

EXTRA-FAMILIAL SEXUAL ABUSE

THERESE G R E G O R Y - B I L L S

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

M E L A N I E RHODEBACK

Rhodeback and Associates, Friendswood, TX, USA

Abstract--The Diagnostic Inventory of Personality and Symptoms (DIPS) was used to assess psychopathology in a

clinical sample of 30 women with histories of intra-familial sexual victimization, 22 women with histories of extrafamilial sexual victimization, and 30 women with no victimization experiences. The present study examines whether

the relative/nonrelative issue is significant to the impact of sexual victimization experiences. A clinical comparison

of two point code types indicated that both sexually abused groups could be characterized as suffering an Affective

Depressed-Dissociative Disorder. However, profile shapes produced for the intra- and extra-familial abused groups

differed. A discriminant function developed via step wise selection procedures incorporated 12 of the 14 scales,

correctly classifying 94% of the individuals (49 of 52) as members of the extra or intra-familial groups. Profile

analyses, discriminant analyses, clinically descriptive comparisons, and post hoc analyses of individual scales all

revealed that psychopathology is much more evident in those who have experienced sexual abuse. Methodological

considerations are highlighted and implications for treatment and research are addressed.

Key Words--Incest, Sexual abuse, Psychopathology, Dissociation.

INTRODUC~ON

M A N Y R E C E N T S T U D I E S have investigated the persistent, negative impact of childhood

and adolescent sexual victimization on later adult psychological functioning and adjustment

(Briere, 1992; Ellenson, 1986; Gelinas, 1983; Gorcey, Santiago, & McCall-Perez, 1986; Hays,

1985; Herman, Russell, & Trocki, 1986; Westerland, 1992). These investigations have assumed

five basic forms: (a) Qualitative descriptive and interpretive reports of clinical observations

(Brooks, 1985; Ellenson, 1986; Gelinas, 1983; O'Brien, 1987; Sloan & Leichner, 1986; Summit & Kryso, 1978); (b) Quantitative investigations o f psychopathology using instruments

such as the M M P I (Meiselman, 1980; Scott & Thoner, 1986; Tsai, Feldman-Summers, &

Edgar, 1979); (c) Comparative research among victims of sexual abuse and nonvictimized,

maladjusted samples (Brooks, 1985; Gorcey et al., 1986; Meiselman, 1980; Scott & Thoner,

1986; Tsai et al., 1979; Winterstein, 1982); (d) Comparisons of psychological functioning and

adjustment among w o m e n who experienced sexual abuse in clinical versus nonclinical samples

(Herman, Russell, & Trocki, 1986; Tsai et al., 1979); and (e) Research on the various circumstances associated with the experience of sexual abuse (Courtois & Watts, 1982; Sloane &

Received for publication December 6, 1989; final revision received November 5, 1993; accepted November 20, 1993.

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Therese Gregory-Bills, Ph.D., 8923 Hickory Hill Avenue, Lanham, MD

20706.

177

178

T. Gregory-Billsand M. Rhodeback

Karpinski, 1942; Tsai et al., 1979). Several scholars have addressed the initial consequences

of incest and sexual abuse (Adams-Tucker, 1982; Anderson, Bach, & Griffith, 1981; Brooks,

1985; DeFrancis, 1969; Friedrich, Urquiza, & Beilke, 1986). Others have addressed the long

term consequences (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Courtois, 1979; Ellenson, 1986; Gelinas, 1983;

Gorcey et al., 1986; Tsai & Wagner, 1978).

The empirical literature is quite consistent in demonstrating the negative impact of sexual

molestation on emotional functioning and adjustment (Adams-Tucker, 1982; Herman et al.,

1986; Scott & Thoner, 1986). However, as portrayed in the literature review of Browne and

Finkelhor (1986) attempts to describe variations in impact as a derivative of circumstances

have led to inconsistencies. LaBarbera, Martin, and Dozier (1980), Henderson, (1983), Pelletier

and Handy (1986), and Emslie and Rosenfeld (1983) are among those clinicians who suggest

that inconsistent findings may be attributed to an exclusive research focus on the sexual

component of the abuse as the factor responsible for the psychological damage. The familial

circumstances are frequently neglected and in many studies, the source of victimization itself

(e.g., family member or nonrelative/stranger) is not distinguished. Children and adolescents

may have experienced sexual abuse perpetrated by family members (intra-familial abuse) or

by individuals external to the family (extra-familial abuse). This key experiential difference

may be manifest in distinguishable psychological impairment and functional adjustment.

Studies by Finkelhor (1979, 1984) and Gruber and Jones (1983) comprise the relatively

limited efforts aimed at describing the family characteristics associated with extra-familial

abuse. According to their research efforts, marital conflicts, disruptions of the family unit,

poor maternal relations, and the absence of a parent were characteristics strongly related to

extra-familial child abuse. The absence of the mother was a particularly important risk factor.

Family characteristics associated with intra-familial sexual abuse (incest) have been studied

much more extensively than those associated with extra-familial sexual abuse (Emslie &

Rosenfeld, 1983; Forward & Buck, 1978; Goodwin, Cormier, & Owen, 1983; Pelletier &

Handy, 1986; Sgroi, 1982; Stern & Meyer, 1980). These families are characterized by social

isolation, secrecy, and blurred generational and role boundaries. Children growing up in these

types of families are frequently witness to female powerlessness and male dominance and

control. The children often take on parenting roles resulting in problems with their own

emotional and social development.

Potential differences in the nature and extent to which extra- or intra-familial abuse may

impact later psychological functioning and adjustment are deducible from the literature. For

example, the intra-familial impact of betrayal of trust and the pathological family relational

dynamics associated with intra-familial abuse have not been characteristically related to victims

of extra-familial abuse. Conversely, consequences of greater fear (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986)

and more severe trauma (Brothers, 1982) have been reported when the perpetrator is a stranger

or is less well-known to the victim. There is no intent to suggest that one form of abuse is

more harmful than another in any absolute sense. Rather, the intent is to suggest that there

are differences in the type of harm caused by different sources of abuse, and ultimately,

differences in the form of psychopathology manifested.

The purpose of this study is to contribute to a better understanding of the potentially different

effects that intra- versus extra-familial sexual abuse may have on psychological functioning

and adjustment. Two research questions are posed: (a) Do the psychological profiles of individuals with histories of intra- and extra-familial abuse differ? (b) Are the psychological profiles

of these two groups distinguishable from those individuals who have not experienced sexual

abuse? Answers to these questions provide information of relevance to understanding, treatment

and directions for future research efforts.

Intra-family versus extra-familysexual abuse

179

METHOD

Subjects

Participants in this study were recruited from mental health agencies, incest survivor groups

and private therapists in the Houston, Texas area. Participants comprising the clinical, nonsexually abused group (N = 30) were screened to ensure that they had not been victims of

sexual abuse. The extra-familial group was composed of women who reported experiences of

childhood sexual abuse by individuals who were not in kinship roles (N = 22). The intrafamilial group was composed of women reporting childhood or adolescent incest (N = 30),

wherein a definition of incest provided by Sgroi, Blick, and Porter (1982) was invoked. This

definition suggests that incest includes any form of sexual activity performed between a child

and a parent or stepparent, extended family member or surrogate parent (common law spouse,

foster parent). The crucial psychosocial dynamic imbedded within this definition is the exploitation of a child's dependency needs by persons in kinship roles.

Measures

Participants with histories of intra- and extra-familial sexual victimization independently

completed questionnaires which asked them to provide background information about themselves and their experiences pertaining to the abuse. Data were gathered on the following

variables: present age, highest degree attained, length of time in therapy, age of abuse onset,

duration of the abuse, degree of violation, the involvement of violence and force, relation to

perpetrator, whether they told anyone about the abuse, and if so, whether the support was

positive or negative. The degree of violation was measured in keeping with a category typology

defined by Russell (1983):

1. Least Serious Sexual Abuse included experiences ranging from kissing, intentional sexual

touching of the buttocks, thigh, leg or other body part, including contact with clothed

breasts or genitals, whether by force or not;

2. Serious Sexual Abuse, included experiences ranging from forced digital penetration of the

vagina to nonforceful breast Contact or simulated intercourse; and

3. Very Serious Sexual Abuse included experiences ranging from intercourse, oral genital

contact to anal intercourse, whether by force or not.

Those who had not been sexually abused (the control group) provided data on the following

variables: present age, highest degree attained, length of time in therapy, and whether or not

they had been sexually victimized. All participants completed the Diagnostic Inventory of

Personality and Symptoms (DIPS) (Vincent, 1985). This is a brief, 171-item test of psychopathology consisting of a 4-item validity scale, 11 scales that correspond to Axis I Diagnostic

Categories of the DSM III (APA, 1980) and three Character Disorder Scales corresponding

to a collapsed version of the Axis H Diagnosis of the DSM III (Vincent, 1987a). Scale rifles

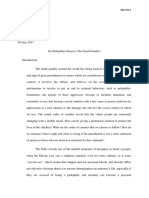

and descriptions are provided in Figure 1. This instrument was selected for the following

reasons: (a) It contains a standardized measure of dissociation. This measure is important in

evaluating the impact of abuse on adult functioning because dissociation is a commonly

employed coping strategy associated with abusive experiences (Brier, 1992; Maltz & Holman,

1987; O'Brien, 1987; Westerlund, 1992). (b) The instrument contains standardized measures

of distinctive clinical symptoms found in individuals with earlier experiences of sexual victimization. Symptoms such as somatization, anxiety, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and depression

are all manifestations of the emotional and psychological impact of experiences of sexual

victimization (Briere, 1992; Briere & Runtz, 1988; Brooks, 1985; Gelinas, 1983).

180

T. Gregory-Bills and M. Rhodeback

1) Alcohol Abuse.

The nature and extent of alcohol dependency

2) Drug Abuse.

The nature and extent of drug abuse

3) Schizophrenic Psychosis.

Psychological alienation, confused thinking and reality distortion

4) Paranoid Psychosis.

Suspiciousness, wariness, resen*~nt and anger; hypervigiliance and hostile paranoia

of psychotic proportions; guarded; oversensitivity

5) Affective Depression.

Marked feelings of dysphoria; loss of interest or pleasure; depression is likely

6) Affective Excited.

Elevated expansive mood; easily irritated; restless; distraction and hyperactivity; manic features may

he present; apt to be restless; energetic and distractable; irritable agitation

7) Anxiety Disorder.

Anxiety; tension and apprehension; compulsion, panic; Feelings of anxiety

8) Somatoform Disorder.

Indicates psychosomatic component; Significant symptoms are expressed in any actual or reported

incidence of illness

9) Dissociative Disorder.

Feelings of unreality; depersonalization; problems with identity

10) Stress Adjustment.

Amount of environmental stress in past year such as death of spouse, marriage, disabled, chronic illness,

pregnancy

11) Psychological Factors Affecting Health.

Number of conditions in which psychological factors often contribute to onset of problems;person is apt

to physiological illness under stress such as ulcers, arrhythmia, migraines, asthma; arthritis or nausea

12) Withdrawn Character.

Significant eccentricities; apt to be withdrawn suspicious and isolated; unusual presentation of self may

he present; significant discomfort in interpersonal relationships due to fear distrust or apathy. Paranoid,

schizotypal, schizoid, or avoidant personality

13) Immature Character.

Dramatic, emotional or erratic; hedonistic, impulsive, emotionally labile and exploitative; irresponsible

and self centered ranging from ego-centric self-indulgence and neglect of responsibility to substance

abuse and legal problems. Difficulties in sustaining long term relationships and marital difficulty;

histrionic, narcissistic, and antisocial or borderline personality

14) Neurotic Character.

Anxious or fearful cluster of DSM III: overconscientious; sensitive; passive and rigid; negative toward

self and chronically anxious; stable family life and capable of forming lasting relationships; avoidant,

dependent, compulsive or passive aggressive

Figure 1. DIPS scales and scale descriptors.

The instrument was developed from the description and criterion sections for the various

disorders o f the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III (DSM III) (American

Psychological Association, 1980), thus ensuring content validity. Comparisons o f mean profiles

produced by normal subjects, private patients, and Veteran's Administration patients have

indicated that the instrument was able to differentiate normality from abnormality, thus indicating criterion validity. Principal components analysis o f the instrument produced three factors,

accounting for 70% o f the total item variance, indicating an internally consistent instrument,

and evidence of construct validity. The instrument has been subject to test-retest, yielding a

reliability coefficient o f .78 (Vincent, 1985).

Procedure

Participants were asked to complete the DIPS and the retrospective, anonymous questionnaire

containing the background measures. The instruments were accompanied by a cover letter that

Intra-family versus extra-family sexual abuse

181

Table 1. Background Characteristics for the Extra-Familial, lntra.Familial, and Control Groups

Present Age

18-25 years

26-33 years

34-41 years

42-48 years

Education

<High School

High School

Some College or Technical School

Bachelors Degree

Some Graduate Work

Masters Degree

Ph.D. Degree

Years of Therapy

<1 year

1-2 years

2.5-5 years

6-10 years

11- 15 years

16-20 years

Extra-Familial

N = 22

Intra-Familial

N = 30

Control

N = 30

5

7

6

4

23

32

27

18

4

13

8

5

13

43

27

17

8

10

8

4

27

33

27

13

0

5

8

4

0

5

0

0

23

36

18

0

23

0

2

6

11

6

2

I

2

7

20

37

20

7

3

7

0

4

11

6

5

3

1

0

13

37

20

17

10

3

3

10

6

1

1

1

14

46

27

5

5

5

6

3

8

11

1

l

20

10

27

37

3

3

5

4

11

8

2

0

17

13

37

27

7

0

d e s c r i b e d the research project, the researcher and their rights as subjects. The purpose o f this

study was presented to the subjects as an investigation to obtain information on the impact o f

sexual v i c t i m i z a t i o n on adult adjustment. It was e x p l a i n e d that the study was d e s i g n e d to

facilitate understanding and treatment.

Participants were requested to c o m p l e t e the questionnaire in their h o m e s and return in a

sealed e n v e l o p e ( p r o v i d e d b y the investigator) within 2 weeks. These were m a i l e d to, or p i c k e d

up b y the researcher. Subsequently, the D I P S scale scores were tallied b y hand utilizing the

scoring sheet d e s i g n e d for the instrument. The profiles were screened for validity by e x a m i n i n g

the validity scale contained in the DIPS. A l l participants p r o d u c e d valid profiles.

RESULTS

Background Variables

F r e q u e n c y distributions constructed from data collected on the b a c k g r o u n d variables relevant

to all three groups are p r o v i d e d in T a b l e 1. T a b l e 2 includes distributions for those b a c k g r o u n d

variables applicable o n l y to the extra- and intra-familial groups. A s indicated in Table 1, all

three groups were similar in terms o f age and education.

P r e l i m i n a r y statistical analyses were c o n d u c t e d to assess which, if any, o f four b a c k g r o u n d

variables should be e m p l o y e d as covariates in analyses d e s i g n e d to c o m p a r e the p s y c h o p a t h o l o g y o f intra- and extra-familial sexually a b u s e d groups. The results o f the p r e l i m i n a r y analyses

r e v e a l e d that the groups d i d not differ in the a m o u n t o f therapy received, t (50) = - 1 . 1 9 , p

> .20 and the severity o f the sexual violation, X 2 (2) = 3.84, p > .10. The two groups were

distinguishable with respect to the average age the sexual abuse began, t (50) = 3.31, p <

.01 and the duration o f victimization, t (50) = - 2 . 7 4 , p < .01. Participants c o m p r i s i n g the

intra-family group tended to b e y o u n g e r at the t i m e o f initial abuse, ( M e a n age o f 5), and

sexually abused for a l o n g e r time p e r i o d ( M e a n o f 8.13 years) than those w h o were m e m b e r s

182

T. Gregory-Bills and M. Rhedeback

Table 2. Background Characteristics Relevant to the Extra-Famillal and Intra-Familiai Groups

Age of Abuse Onset

0-3 years

4-7 years

8-11 years

12-15 years

16-17 years

Duration

Once

3-11 months

1-2 years

3-5 years

6-10 years

11-15 years

16-28 years

Degree of Violation

1 Least Serious Sexual Abuse

2 Serious Sexual Abuse

3 Very Serious Sexual Abuse

Told or Kept Secret

Told

Kept Secret

Support or No Support

Told and Supported

Told and Not Supported (blamed, not believed, sent away)

Extra-Familial

(N = 22)

Intra-Familial

(N = 30)

0

13

2

4

3

0

59

9

18

14

10

12

7

1

0

33

40

23

3

0

3

2

4

7

5

1

0

14

9

18

32

23

5

0

0

1

7

5

8

5

4

0

3

23

17

27

17

14

0

5

17

0

23

77

2

11

17

7

37

57

6

16

27

73

10

20

33

67

2

4

33

67

2

8

18

80

o f the extra-familial group ( M e a n age o f 8.8 and M e a n duration o f 4.09 years). Nevertheless,

there was no statistically significant multiple correlation b e t w e e n factor scores derived from

a principle c o m p o n e n t s analysis o f the 14 measures and age the abuse began, (R = .27), F (3,48)

= 1.26, p > .05, nor was there a significant m u l t i p l e correlation b e t w e e n these c o m p o n e n t s and

the duration o f the abuse, (R = .34), F (3,48) = 2.04, p > .05. The three-factor principal

c o m p o n e n t s solution rather than the 14 i n d i v i d u a l m e a s u r e s were e m p l o y e d in these p r e l i m i n a r y

analyses b e c a u s e there was a desire to c o n s e r v e an e x p e r i m e n t - w i s e error rate that w o u l d have

been greatly inflated had p r e l i m i n a r y analyses i n v o l v e d 28 significance tests (14 measures X

2 b a c k g r o u n d variables). These p r e l i m i n a r y analyses indicated that there was no statistically

valid reason for e m p l o y i n g either age the abuse b e g a n or duration o f abuse as covariates in

analyses d e s i g n e d to c o m p a r e extra- and intra-familial a b u s e d groups on measures o f p s y c h o p a thology.

Profile analyses ( G e i s s e r & Greenhouse, 1959; Stevens, 1986) were e m p l o y e d to test two

hypotheses: (a) The p s y c h o l o g i c a l profiles o f the intra- and extra-familial groups w o u l d differ,

and (b) the p s y c h o l o g i c a l profiles o f those not abused w o u l d differ f r o m the c o m b i n e d intraand extra-familial groups. To ensure that the interaction w o u l d not be a scaling artifact,

individual scale scores were standardized prior to analyzing the profiles. In addition, discriminant analyses and canonical correlations were e m p l o y e d as analytical strategies for describing

the nature o f group differences and the strength o f the relation b e t w e e n the measures o f

p s y c h o p a t h o l o g y and group m e m b e r s h i p .

Comparison of Intra- and Extra-Familial GrouPs

A c o m p a r i s o n o f the extra- and intra-familial groups r e v e a l e d that the profiles were not

parallel, T 2 (13, 38) = 1.20, F = 3.50, p < .005. This result supports the assertion that extra

Intra-family versus extra-family sexual abuse

183

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics, Step-Wise Discrlminant Analyses and Post-Hoe Results for the lntra and Extra

Familial Group Comparisons

Stepwise Discrminant Analysis

Extra-Familial

Intra-Familial

Scale

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Structure

Coefficients

Entry

Order

Alcohol Abuse

Drug Abuse

Schizophrenic Psychosis

Paranoid Psychosis

Affective Depression

Affective Excited

Anxiety Disorder

Somatoform Disorder

Dissociative Disorder

Stress Adjustment

Disorder

11) Psychological Factors

Affecting Physical

Health

Character Disorder Scales

12) Withdrawn

13) Immature

14) Neurotic

1.27

0.86

3.32

3.96

12.05

2.32

9.86

4.55

4.00

2.09

1.35

1.13

1.56

2.94

4.81

1.21

2.61

1.57

2.29

1.57

1.07

1.77

2.97

2.70

11.53

1.93

10.43

4.47

4.23

1.80

1.72

2.70

2.39

2.04

5.34

1.44

5.32

3.52

3.31

1.75

.39

-.96

N.E.

-.34

-.81

.45

-1.10

.55

-1.00

.36

11

2

10

5

9

8

7

3

6

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

3.00

.76

2.77

2.19

.36

12

ns

7.23

2.32

12.73

2.16

1.17

2.68

4.70

2.83

10.77

3.12

2.96

4.10

1.34

N.E.

1.47

11

*

ns

ns

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

t-Test

* Boneferroni inequality of .15 applied to control type 1 error; p < .01.

N.E. = not entered into the step-wise discriminant analysis model.

ns = not statistically significant,

and intra-familial sexual abuse victims experience different psychological symptoms. The

canonical correlation between group membership and the 14 measures was .81, ~(2 (12) =

46.18, p < .001, thus indicating that more than 64% o f the variance in the scales separated

these two groups. A step-wise discriminant model indicated that, despite high intercorrelations

among the 14 measures o f psychopathology, all but two contributed variance separating the

two groups. The intra- and extra-familial groups were distinguishable on the basis o f a model

that jointly considered Withdrawal, Drug Abuse, Dissociative Disorder, Neuroses, AffectiveDepression, Stress Adjustment Disorder, Somatoform Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, AffectiveExcited, Paranoid Psychosis, Alcohol Abuse, and Psychological Factors Affecting Physical

Condition. Mean scores for each scale and the results o f the discriminant analysis are provided

in Table 3.

The discriminant model resulted in a 94% hit rate when employed to classify participants

into the extra- and intra-familial groups. O f the 30 intra-familial subjects and 22 extra-familial

subjects, 97% (29) and 91% (20), respectively, were correctly classified. Post hoe comparisons

o f the 14 scale scores were conducted so that a description o f group differences on each

individual scale might be provided. An error rate o f . 15 was divided among the 14 comparisons

in keeping with the Boneferroni approach to controlling a Type I error rate, resulting in a

group difference only on the Withdrawn Character Disorder scale.

Considered collectively, the profile analyses, discriminant analyses, and post hoc comparisons o f the 14 scale scores, indicate that in order to detect differences in the psychological

functioning o f intra- and extra-familial abused groups, it is necessary to evaluate an entire

profile as a linear function o f psychological measures. It is the profile, rather than an individual

variable that captures the principle psychological differences. A clinical interpretation o f the

intra- and extra-familial groups' psychological state was made by invoking the traditional

strategy for describing a DIPS psychological profile. D I P S ' scales one through 11 were first

reviewed to identify the two scales which, after transformation to T scores, the groups scored

184

T. Gregory-Bills and M. Rhodeback

o

-..42-

Intra-Familial

Extra-Familial " - - - - - Control

90

. D

x

t

80

/'+"

p

I

x

70

j~

8

60

50

40

AA

DA

SP

PP

AD

I'

AE

AX

SO

DD

SA

PC

WC

lC

NC

Category

PP

Alcohol Abuse

Drug Abuse

Schizophrenic Psychosis

ParanoidPsychosis

AE

AX

SO

DD

AD

Affective Depressed

SA

PC

AA

DA

SP

Affective Exciled

Anxiety Disorders

Somatoform Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

Stress Adjustment Disorders

Psychological Factors Affecting

Physical Condition

WC

IC

NC

WithdrawnCharacter

lmmaturc Character

NeuroticCharacter

Figure 2. Diagnositic inventory of personality and symptons.

the highest and in excess of a 70 T-Score. Two point code types are traditionally used in clinical

descriptions of DIPS psychological profiles and correspond to typical diagnoses described in

the DSM III (Duthie & Vincent, 1986; Williams, Coker, Vincent, Duthie, Overall, & McLauglin, 1988). Whereas interpretations of 2 point code types made from scales 1-11 corresponded

to an Axis I diagnosis in the DSM III, interpretations of 2 point code types made from scales

12-14 corresponded to an Axis II diagnosis. Figure 2 provides graphic results of the T-scores

associated with the group means for all three groups.

This descriptive assessment indicates that both the intra- and extra-familial groups scored

the highest on the Affective-Depressed (AD) and Dissociative Disorders (DD) scales. An ADDD two point code type (also referred to as a 5 - 9 code type) represents a primary Axis I

diagnosis in which the persons reported marked feelings of dysphoria and a significant loss

of interest or pleasure. They were likely to have very significant depression accompanied by

a very significant amount of dissociative phenomena. Feelings of unreality were present,

depersonalization was likely and problems with identity were indicated.

Applying the two point code type interpretive scheme to the three character disorder scales,

withdrawn (12); Immature (13); and Neurotic (14), the results indicate that the extra-familial,

sexually abused group scored in excess of a T-70 on the Neurotic and Withdrawn scale. The

intra-familial abused group scored in excess of a T-70 only on the Neurotic scale. As previously

indicated, a significant difference was obtained for the Withdrawn scale, thus providing preliminary statistical support for a clinical distinction in the Axis 2 diagnosis.

The Withdrawn-Neurotic code type that characterizes the extra-familial group indicates a

combination of oversensitivity and social withdrawal with anxiety and passivity that is most

apt to be seen in individuals with an avoidant personality (Vincent, 1987b). The Neurotic code

type that characterizes the intra-familial group correspond to the anxious or fearful cluster of the

DSM III personality disorders such as avoidant, dependent compulsive, and passive aggressive

disorders. Such individuals are described by Vincent (1987b) to be overconscientious, sensitive,

Intra-family versus extra-family sexual abuse

185

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics, Step-Wise Discriminant Analyses and Post Hoc Results for the Combined Extra

Familial Group Comparison with the Non-Abused (Control) Group

Extra-Intra

Familial

Stepwise Discriminant

Analysis

Nonabused

Scale

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Structure

Coefficients

Alcohol Abuse

Drug Abuse

Schizophrenic Psychosis

Paranoid Psychosis

Affective Depression

Affective Excited

Anxiety Disorder

Somatoform Disorder

Dissociative Disorder

Stress Adjustment

Psychological Factors

Affecting Physical

Health

Character Disorder Scales

12) Withdrawn

13) Immature

14) Neurotic

1.15

1.35

3.11

3.23

11.75

2.10

10.19

4.50

4.13

1.92

2.87

1.56

2.21

2.06

2.51

5.08

1.35

4.36

2.83

2.90

1.671

1.73

.90

.73

1.33

1.43

5.90

1.47

6.03

2.30

.87

1.80

1.63

1.42

1.60

1.16

1.22

4.33

1.72

3.67

2.65

1.01

1.69

1.47

N.E.

-.50

N.E.

N.E.

.59

N.E.

N.E.

.36

.69

-.39

N.E.

5.77

2.62

11.60

3.01

2.37

3.67

2.53

1.57

7.27

1.98

1.92

4.18

N.E.

N.E.

N.E.

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

11)

Entry

Order

4

2

5

1

3

t-Test

ns

ns

*

*

*

ns

*

*

*

ns

*

*

ns

*

*p < .01, 80 df where an error rate of .15 was divided among 14 comparisons.

N.E. = not entered into the step-wise discriminant analysis model.

ns = not statistically significant.

passive, and rigid. Persons o f this profile type are also described to be negative towards

themselves and chronically anxious.

Comparisons of the Combined Extra- and Intra-Familial Groups with the Non-Abused,

Control Group

A c o m p a r i s o n o f the c o m b i n e d extra- and intra-familial groups with the nonabused, control

group revealed that these profiles were not parallel, T 2 (13, 68) = .50; F = 2.62, p < .005.

This result replicates previous research that has shown that victims o f sexual abuse experience

clinical s y m p t o m s differing from those w h o have not been abused (Gelinas, 1983; G o r c e y et

al., 1986; H e r m a n et al., 1986). Table 4 illustrates m e a n scale scores for the control group as

well as the c o m b i n e d intra- and extra-familial groups. In summary, the p s y c h o l o g i c a l profiles

are distinguishable.

The canonical correlation b e t w e e n group m e m b e r s h i p and the 14 variables, when the two

groups were c o m p o s e d o f the control (those who had not been abused) and the c o m b i n e d

intra-extra familial groups was .65, X 2 (5) = 42.34, p < .001, thus indicating that 42% o f the

variance in the scale scores separates the groups.

A step-wise discriminant m o d e l was e m p l o y e d to explore and describe group differences

b e t w e e n the c o m b i n e d extra- and intra-familial victims, with those w h o had not been sexually

abused. The results are presented in Table 4. A s indicated, only 5 o f the 14 variables were

n e e d e d to distinguish these groups, including those designed to measure Dissociative Disorder,

Affective Depression, Stress Adjustment, Drug Abuse, and S o m a t o f o r m Disorder. I m p l i e d is

that the remaining variables a d d e d no variance to group separation b e y o n d that which these

five variables contributed. The m o d e l resulted in an 87% hit rate, with 85% o f those subject

to abuse (44 o f 52) being correctly classified and 90% o f those not being abused (27 o f 30)

being correctly classified.

186

T. Gregory-Billsand M. Rhodeback

The graphic illustration provided in Figure 2 indicates that the nonabused, control group

profile was completely within the normal range, that is a T score of less than 70 on all 14

measures, and is clearly distinguishable from those who had been sexually victimized. Post

hoc comparisons of scale score means indicate that individuals comprising the combined extraand intra-familial groups produced significantly higher scores on 9 of the 14 measures of

psychopathology, including Schizophrenic Psychosis, Paranoid Psychosis, Affective Depression, Anxiety Disorder, Somatoform Disorder, Dissociative Disorder, Psychological Factors

Affecting Physical Condition, Withdrawn Character, and Neurotic Character. The groups did

not differ on scales designed to measure Alcohol Abuse, Drug Abuse, Affective-Excited, Stress

Adjustment, and Immature Character Disorder.

DISCUSSION

It was hypothesized that the psychological profiles of individuals with histories of intraand extra-familial abuse would differ. The results support the hypothesis. Profile shapes produced for the intra- and extra-familial abused groups differed, and a discriminant function

developed via step wise selection procedures incorporated 12 of the 14 scales; however, post

hoc comparisons of 14 scale means revealed a statistically significant difference on only one,

the Withdrawn Character Disorder scale, and a clinical comparison of two point code types

indicated that both groups could be characterized as suffering a 5 - 9 disorder (AffectiveDepressed-Dissociative). Although seemingly contradictory, the profile and discriminant analyses differ from the post hoc comparisons of individual scales and clinical descriptions in that

they make use of a linear combination of the variables and do not ignore the intercorrelations

among the 14 measures. While differences on most of the 14 scales are not large enough to

produce significant results individually (perhaps due to small group n sizes), a linear combination of the intercorrelated variables does provide enough reliable variance to permit distinguishing the profiles, and to produce a function that correctly classifies 94% of the individuals (49

of 52) as members of the extra- or intra-familial groups. Some caution is necessary in interpreting the discriminant model and the classification rates since the subject to variable ratio is

less than desirable, and there exists a need to cross validate the discriminant function. Cross

validation through replication of the study would serve as a highly instructive avenue for

additional research.

The existence of a linear function which differentiates extra and intra-familial groups is not

surprising, however, the nature of the observed differences are somewhat unexpected. For

example, the extra-familial group scored higher than the intra-familial group on the Withdrawn

Character Disorder scale, one of three scales used in formulating an Axis II diagnosis. Indeed,

the extra-familial group scored higher than the intra-familial group on nine of the 12 variables

comprising the discriminant function, although individual comparisons of scale means were

not necessarily large enough to achieve statistical significance.

The direction of the difference on the Withdrawn scale may reflect a generalized withdrawal

response to the arousal of extreme fear, as would be the case if a stranger assaulted (such as

rape) the child. It is also possible that sensitive material and the defensive structure of the

respondent distorted the self-evaluative data. If memory has been flawed because of massive

denial or repression, self perceptions may produce an entirely inaccurate assessment of psychological adjustment. Unfortunately, this possibility bears on all research efforts aimed at defining

the psychopathological implications of sexual victimization. Response bias may also occur if

the type of abuse (extra- vs. intra-familial) is nested within different forms of therapeutic

interventions. This and other potential forms of selection bias emphasize the need for replication

using alternative subject sources.

Intra-family versus extra-family sexual abuse

187

The notion of an "incestuous family" provides a conceptual framework for understanding

the effects of sexual abuse within the family. Familial circumstances may also serve as a

conceptual framework for understanding the severity of pathology observed in the extrafamilial group. Extra-familial abuse is, alone, a traumatic experience. When combined with

familial circumstances that inhibit the child from talking about the victimization, or when

blamed and not supported by the family (as was the case for the majority of the extra-familial

group who told family members of their experiences), the trauma is likely to be aggravated.

Further, it have been suggested that extra-familial abusers intuitively select those whose character and emotional development have been impaired due to family dysfunction (Finkelhor,

1984; Forward & Buck, 1978). Whether or not the family serves as a gateway to extra-familial

abuse, or aggravation of a trauma unrelated to family dysfunction is worthy of further research,

and necessary for further understanding the psychopathology observed in this study.

The study indicates that contradictory results may be obtained if investigators ignore methodologically distinctive ways of analyzing differences between intra- and extra-familial, sexually

abused groups. This may be due implicitly to the statistical procedures, or possibly attributable

to the existence of differences so subtle in the psychopathologies of the intra- and extrafamilial groups that more powerful analyses, such as profile and discriminant analyses are

necessary to detect them. This is an important question bearing on the treatment of these

individuals since an understanding of these subtle differences may be critical to effective

therapeutic intervention. At the very least, this study indicates that it is a question worthy of

additional inquiry.

The hypothesized difference between those who had been sexually abused and those who

had not been abused were clearly supported. The results offer none of the interpretive complexities found when attempting to compare intra- and extra-familial group differences. The profile

analyses, discriminant analyses, clinically descriptive comparisons, and the post hoc analyses

of individual scales all reveal that psychopathology is much more evident in those who have

been victims of sexual abuse. The results complement previous research findings that have

demonstrated differences between sexually abused and nonsexually abused psychopathology

(e.g., Briere & Runtz, 1988). The results also strongly point to the significance of dissociative

and depressive symptomology among individuals who have had experiences of sexual abuse

identified both clinically (Gelinas, 1983; Herman et al., 1986; Maltz & Holman, 1987; O'Brien,

1987) and, more recently, empirically (Briere & Runtz, 1988; Gregory-Bills, 1990). These

investigations have related the chronic depression to long term low self esteem, unresolved

feelings of shame and guilt, experiences of powerlessness and unexpressed anger. Dissociation

is described to have been a coping mechanism learned during the abuse (Maltz & Holman,

1987). In many cases, dissociation becomes a general and automatic response to other situations

in which strong emotions are evoked (Maltz & Holman, 1987; O'Brien, 1987). A future study

might include another population with expected pathological deviancy in the analysis. This

would serve to address the uniqueness of depressive and dissociative symptoms to individuals

with experiences of sexual victimization.

REFERENCES

Adams-Tucker, C. (1982). Proximate effects of sexual abuse in childhood: A report on 28 children. American Journal

of Psychiatry, 139(10), 1252-1256.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed). Washington,

DC: Author.

Anderson, S. C., Bach, C. M., & Griffith, S. (1981). Psychosocial sequelae in intra-familial victims of sexual assault

and abuse. Paper presented at the Third International Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect. Amsterdam, The

188

T. Gregory-Bills and M. Rhodeback

Netherlands. Cited in A. Browne & D. Finkelhor (1986), Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research.

Psychological Bulletin, 99, 66-77.

Briere, J. N. (1992). Child abuse trauma: Theory and treatment of the lasting effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Briere, J., & Runtz, M. (1988). Symptomatology associated with childhood sexual victimization in a nonclinical adult

sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 12, 51-59.

Brooks, B. (1985). Sexually abused children and adolescent identity development. American Journal of Psychotherapy,

XXXIX, 401-410.

Brothers, D. (1982). Trust disturbances among rape and incest victims. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Yeshiva

University. Dissertation Abstracts International, No. 8220381.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin,

99, 66-77.

Courtois, C. A. (1979). The incest experience and its aftermath. Victimology: An International Journal, 4, 337-347.

Courtois, C. A., & Watts, D. L. (1982). Counseling adult women who experienced incest in childhood or adolescence.

The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60, 275-279.

DeFrancis, V. (196). Protecting the child victim of sex crimes committed by adults. Denver, CO: American Humane

Association.

Duthie, B., & Vincent, K. R. (1986). Diagnostic hit rates of high point codes for the Diagnostic Inventory of Personality

and Symptoms using random assignment base rates and probability scales. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42,

612-614.

Ellenson, G. S. (1986). Disturbances of perception in adult female incest survivors. Social Casework: The Journal of

Contemporary Social Work, March, 149-159.

Emslie, G. J., & Rosenfeld, A. (1983). Incest reported by children and adolescents hospitalized for severe psychiatric

problems. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 708-711.

Finkelhor, D. (1979). Sexually victimized children. New York: Free Press.

Finkelhor, D, (1984). Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. New York: Free Press.

Forward, S., & Buck, C. (1978). Betrayal of innocence: Incest and its devastation. Los Angeles, CA: J. P. Tarcher,

Inc.

Friedrich, W. N., Urquiza, A. J., & Beilke, R. (1986). Behavioral problems in sexually abused young children. Journal

of Pediatric Psychology, 11, 47-57.

Geisser, S., & Greenhouse, S. W. (1959). On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika, 24, 95-112.

Gelinas, D. (1983). The persisting negative effects of incest. Psychiatry, 46, 312-332.

Goodwin, J., Cormier, L., & Ownen, J. (1983). Grandfather-granddaughter incest: A trigenerational view. Child

Abuse & Neglect, 7, 163-170.

Gorcey, M., Santiago, J. M., & McCall-Perez, F. (1986). Psychological consequences for women sexually abused in

childhood. Social Psychiatry, 21, 129-133.

Gregory-Bills, T. E. (1990). Eating disorders and their correlates in earlier episodes of incest. Doctoral Dissertation,

University of Houston. University Microfilms International, No. 9107334.

Gruber, K. J., & Jones, R. J. (1983). Identifying determinants of risk of sexual victimization of youth: A multivariate

approach. ChiM Abuse & Neglect, 7, 17-24.

Hays, K. F. (1985). Electra in mourning: Grief work and the adult incest survivor. The Psychotherapy Patient, 2, 4558.

Henderson, J. (1983). Is incest harmful? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 28, 34-39.

Herman, J., Russell, D., & Trocki, K. (1986). Long-term effects of incestuous abuse in childhood. American Journal

of Psychiatry, 143, 1293-1296.

LaBarbera, J. D., Martin, J. E., & Dozier, J. E. (1980). Child psychiatrists' view of father-daughter incest. Child

Abuse & Neglect, 4, 147-151.

Maltz, W., & Holman, B. (1987). Incest and sexuality. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Meiselman, K. (1980). Personality characteristics of incest history patients: A research note. Archives of Sexual

Behavior, 9, 195-197.

O'Brien, J. D. (1987). The effects of incest on female adolescent development. Journal of the American Academy of

Psychoanalysis, 15, 83-92.

Pelletier, G., & Handy, L. (1986). Family dysfunction and the psychological impact of child sexual abuse. Canadian

Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 407-~12.

Rosenfield, A., Nadelson, C., Krieger, M., & Blackman, J. (1977) Incest and sexual abuse of children. Journal of

Child Psychiatry, 16(2), 327-339.

Russell, D. E. H. (1983). The incidence and prevalence of intra-familial and extra-familial sexual abuse of female

children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 7, 133-146.

Scott, R., & Thoner, G. (1986). Ego deficits in anorexia nervosa patients and incest victims: An MMPI comparative

analysis. Psychological Reports, 58, 839-846.

Sgroi, S. (1982). Handbook of clinical interventions in child sexual abuse. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Sgroi, S., Blick, L., & Porter, F. (1982). A conceptual framework for child sexual abuse. In S. Sgroi (Ed.), Handbook

of clinical intervention in child sexual abuse. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Sloan, G., & Leichner, P. (1986). Is there a relationship between sexual abuse or incest and eating disorders? Canadian

Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 656-660.

Sloane, P., & Karpinski, E. (1942). Effects of incest on the participants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 12,

666-673.

Intra-family versus extra-family sexual abuse

189

Stem, M. J., & Meyer, L. C. (1980). Family and couple interactional patterns in cases of father/daughter incest. In

B. M. Jones, L. L. Jenstrom, & K. McFarlane (Eds.), Sexual abuse of children: Selected readings. Washington,

DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Stevens, J. (1986). Applied multivariate statisticsfor the social sciences. Hillsdale, N J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Summit, R., & Kryso, J. (1978). Sexual abuse of children: A clinical spectrum. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,

48, 237-251.

Tsai, M., Feldman-Surnmers, S., & Edgar, M. (1979). Childhood molestation: Variables related to differential impacts

on psychosexual functioning in adult women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 407-417.

Tsai, M., & Wagner, N. (1978). Therapy groups for women sexually molested as children. Archives of Sexual Behavior,

7, 417-427.

Vincent, K. R. (1985). Manual for the diagnostic inventory of personality and symptoms (DIPS). Richland, WA:

Pacific Psychological.

Vincent, K. R. (1987a). Interrelationships of personality disorders: Theoretical formulations and anecdotal evidence.

Social Behavior and Personality, 15, 35-41.

Vincent, K. R. (1987b). Full battery code book. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Press.

Westerlund, E. (1992). Women's sexuality after childhood incest. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Williams, W., Coker, R. R., Vincent, K. R., Duthie, B., Overall, J. E., & Mclaughlin, E. G. (1988). DSM-III diagnosis

and code types of the diagnostic inventory of personality and symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 326335.

Winterstein, M. (1982). Multiple abuse histories and personality characteristics of incest victims. Unpublished doctoral

dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary. Dissertation Abstracts International, No. 8218612.

R~um6---French abstract not available at time of publication.

Resumen--El Inventario Diagn6stico de Personalidad y Sintomas (DIPS) fue utilizado para evaluar la psicopatologla

de una muestra clfnica de 30 mujeres con historias de victimizaci6n sexual intra-familiar, 22 mujeres con historias

de victimizaci6n extrafamiliar, y 30 mujeres sin experiencias de victimizaci6n. El presente estudio examina si el

aspecto familiar/no familiar es significativo para las consecuencias de las experiencias de victimizacion sexual. Una

comparaci6n clfnica del c6digo de dos puntos indic6 que ambos grupos abusados podffan caracterizarse como sufriendo

un Desorden Depresivo-Disociativo-Afectivo. Sin embargo, los perfiles producidos por los grupos intra y extra

familiares eran diferentes. Una funci6n discriminativa se desarroll6 via procedimientos de selecci6n que incorpor6

doce de las catorce escalas, clasific6 correctamente el 94% de los individuos (49 de 52) como miembros de grupos

intra o extra familiares. Los an~lisis de los perfiles, an~lisis discriminativos, comparaciones clinicamente descriptivas,

y an~lisis pos hoc de las escalas individuales revelaron que la psicopatologfa es mucho mas evidente en aquellos que

han tenido la experiencia de abuso sexual. Se destacaron las consideraciones metodol~igicas y se discutieron las

implicaciones que tienen para el tratarniento y la investigaci6n.

You might also like

- Desordenes Fronterizos y Narcisismo Patologico - Otto KernbergDocument309 pagesDesordenes Fronterizos y Narcisismo Patologico - Otto KernbergpvarillasNo ratings yet

- Statement Validity Assessment Myths and Limitations - DefDocument7 pagesStatement Validity Assessment Myths and Limitations - DefCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- 154940Document12 pages154940Cesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Psycholegal Issues in Child Sexual Abuse Evaluations: A Survey O F Forensic Mental Health ProfessionalsDocument16 pagesPsycholegal Issues in Child Sexual Abuse Evaluations: A Survey O F Forensic Mental Health ProfessionalsCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Variability of Training and Beliefs Among Professionals Who Interview Children To Investigate Suspected Sexual Abuse PDFDocument10 pagesA Study of The Variability of Training and Beliefs Among Professionals Who Interview Children To Investigate Suspected Sexual Abuse PDFCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Pinter-Thom 2010 02thesisDocument352 pagesPinter-Thom 2010 02thesisCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- CornerHouse Interview Protocol ChangesDocument2 pagesCornerHouse Interview Protocol ChangesCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 014521349400119F MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 014521349400119F MainCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Fnbeh 07 00142Document10 pagesFnbeh 07 00142Cesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- ReviewDocument21 pagesReviewCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Child Abuse - in PressDocument38 pagesAssessment of Child Abuse - in PressCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Child Forensic InterviewingDocument22 pagesChild Forensic InterviewingCesc GoGaNo ratings yet

- Review of 35 Child and Adolescent Trauma MeasuresDocument170 pagesReview of 35 Child and Adolescent Trauma MeasuresCatalina Buzdugan100% (5)

- Assessment and Screening Tools For TraumaDocument25 pagesAssessment and Screening Tools For TraumaCesc GoGa100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chantal Robson Examination 06.05.05Document14 pagesChantal Robson Examination 06.05.05MJ BrookinsNo ratings yet

- Richards ComplaintDocument11 pagesRichards ComplaintHelena_RS100% (1)

- Exonerations in 2013Document40 pagesExonerations in 2013stevennelson10No ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument14 pagesResearch Paperapi-220519183100% (5)

- Ply For Gender Neutral Rape Laws: Title Page NoDocument27 pagesPly For Gender Neutral Rape Laws: Title Page NoKeshav VyasNo ratings yet

- 80 Phil LJ697Document15 pages80 Phil LJ697Agent BlueNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Dent Arrest Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesBenjamin Dent Arrest Press ReleaseRyan GraffiusNo ratings yet

- Ekman, Paul - Lying and Deception (1997)Document11 pagesEkman, Paul - Lying and Deception (1997)Darihuz Septimus0% (1)

- Filkehor 1994, Nature Et Scope AbusDocument24 pagesFilkehor 1994, Nature Et Scope AbusArthur ReiterNo ratings yet

- Types of Victimization and Victim ServicesDocument6 pagesTypes of Victimization and Victim ServicesagnymahajanNo ratings yet

- NSVRC Online Resources For SurvivorsDocument12 pagesNSVRC Online Resources For SurvivorsReno PD Victim ServicesNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Srednicki2002Document17 pagesRodriguez Srednicki2002Daniela StoicaNo ratings yet

- Update on Serious and Violent Juvenile Delinquency in the NetherlandsDocument90 pagesUpdate on Serious and Violent Juvenile Delinquency in the NetherlandskhaledNo ratings yet

- PosPap - Felix Natalando - SWISS DelegateDocument3 pagesPosPap - Felix Natalando - SWISS DelegateVavel GrandeNo ratings yet

- Causes and Effects of Teen Sexual Abuse in Bog, JamaicaDocument29 pagesCauses and Effects of Teen Sexual Abuse in Bog, JamaicaAndrea phillipNo ratings yet

- 1Document5 pages1Santosh RathodNo ratings yet

- Pedophiles and Death PenaltyDocument7 pagesPedophiles and Death PenaltyGabriel MoroteNo ratings yet

- Angela Hobday, Kate Ollier - Creative Therapy - Adolescents Overcoming Child Sexual Abuse-Acer Press (2004) PDFDocument224 pagesAngela Hobday, Kate Ollier - Creative Therapy - Adolescents Overcoming Child Sexual Abuse-Acer Press (2004) PDFHelena MNo ratings yet

- Saij-Online Sexual Adjustment Inventory JuvenileDocument10 pagesSaij-Online Sexual Adjustment Inventory JuvenileminodoraNo ratings yet

- An Invisible Crime and Shattered InnocenceDocument6 pagesAn Invisible Crime and Shattered InnocencejensonloganNo ratings yet

- The Child and Youth Law in The PhilippinesDocument31 pagesThe Child and Youth Law in The Philippineschester chesterNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia: Understanding Mental Disorder and AbuseDocument2 pagesPedophilia: Understanding Mental Disorder and AbuseGuilherme Paulino DiasNo ratings yet

- Kimberly'sDocument12 pagesKimberly'skathing gatinNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse, Child Pornography and The Internet: John Carr Internet Consultant, NCHDocument40 pagesChild Abuse, Child Pornography and The Internet: John Carr Internet Consultant, NCHBatataassadaNo ratings yet

- Shaver 1985Document12 pagesShaver 1985Nikoloz NikuradzeNo ratings yet

- Identifying Sexually Abused Children Through Their ArtDocument10 pagesIdentifying Sexually Abused Children Through Their ArtKatya BlackNo ratings yet

- Crimes Against Children Project ReportDocument29 pagesCrimes Against Children Project ReportSumanth DNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse in India - An Analysis: Amisha U. PathakDocument12 pagesChild Abuse in India - An Analysis: Amisha U. Pathaksakshi ranaNo ratings yet

- Admissibility of A Child Witness in The Court of Law - IPleadersDocument5 pagesAdmissibility of A Child Witness in The Court of Law - IPleadersAnkit YadavNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse FactsDocument53 pagesChild Abuse FactsIZZAH ATHIRAH BINTI IZAMUDIN MoeNo ratings yet