Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Manufacturers Vs Meer

Uploaded by

Alandia GaspiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Manufacturers Vs Meer

Uploaded by

Alandia GaspiCopyright:

Available Formats

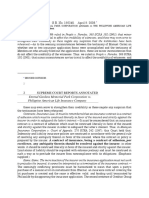

[G.R. No. L-2910. June 29, 1951.

]

THE MANUFACTURERS LIFE INSURANCE CO., PlaintiffAppellant, v. BIBIANO L. MEER, in the capacity as Collector of

Internal Revenue, Defendant-Appellee.

for Appellee.

SYLLABUS

1. LIFE INSURANCE; CASH SURRENDER VALUE. Cash surrender

value "as applied to a life insurance policy, is the amount of money the

company agrees to pay to the holder of the policy if he surrenders it

and releases his claims upon it. The more premiums the insured has

paid the greater will be the surrender value; but the surrender value is

always a lesser sum than the total amount of premiums paid." The

cash value or cash surrender value is therefore an amount which the

insurance company holds in trust for the insured to be delivered to him

upon demand, and is a liability of the company to the insured.

2. ID.; PREMIUM PAID ON AUTOMATIC LOAN HELD SUBJECT TO TAX.

As the insurer agreed to consider the premium paid on the strength

of the automatic loan, which is taken out of the cash surrender value,

the premium is therefore paid by means of a "note" or "credit" or

"other substitute for money", and tax is due thereon under section 255

of the National Internal Revenue Code as amended.

3. ID.; TAXATION; COMPANIES ENGAGED IN BUSINESS IN THE

PHILIPPINES, LIABLE TO TAX; PAYMENT OF PREMIUMS IN A FOREIGN

COUNTRY, DOES NOT EXEMPT. The issuance company claims that as

the advances of premiums were made in Toronto, such premiums are

deemed to have been paid there - not in the Philippines and

therefore those payments are not subject to local taxation. Held: The

loans are made to policy-holders in the Philippines, who in turn pay

therewith the premiums to the insurer through the Manila Branch, and

are therefore taxable locally.

4. INSURANCE COMPANY; CLOSING OF BRANCH OFFICE IN THE

PHILIPPINES DURING THE WAR, DID NOT TERMINATE OPERATIONS OF

THE COMPANY. Although the insurer was not open for new business

because its Manila office was closed, yet if it was collecting premiums

on its outstanding policies, incurring the risks and/or enjoying the

benefits consequent thereto, it was operating in this country.

DECISION

BENGZON, J.:

Appeal from a decision of the Honorable Buenaventura Ocampo, then

judge of the Manila court of first instance, dismissing plaintiffs

complaint to recover money paid under protest for taxes. The case was

submitted upon a stipulation of facts, supplemented by documentary

evidence.

The plaintiff, the Manufacturers Life Insurance Company in a

corporation duly organized in Canada with head office at Toronto. It is

duly registered and licensed to engage in life insurance business in the

Philippines, and maintains a branch office in Manila. It was engaged in

such business in the Philippines for more than five years before and

including the year 1941. But due to the exigencies of the war it closed

the branch office at Manila during 1942 up to September 1945.

In the course of its operations before the war, plaintiff issued a number

of life insurance policies in the Philippines containing stipulations

referred to as nonforfeiture clauses, as follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"8. Automatic Premium Loan. This Policy shall not lapse for nonpayment of any premium after it has been three full years in force, if,

at the due date of such premium, the Cash Value of this Policy and of

any bonus additions and dividends left on accumulation (after

deducting any indebtedness to the Company and the interest accrued

thereon) shall exceed the amount of said premium. In which event the

company will, without further request, treat the premium then due as

paid, and the amount of such premium, with interest from its actual

due date at six per cent per annum, compounded yearly, and one per

cent, compounded yearly, for expenses, shall be a first lien on this

Policy in the Companys favour in priority to the claim of any assignee

or any other person. The accumulated lien may at any time, while the

Policy is in force, be paid in whole or in part.

When the premium falls due and is not paid in cash within the months

grace, if the Cash Value of this policy and of any bonus additions and

dividends left on accumulation (after deducting any accumulated

indebtedness) be less than the premium then due, the Company will,

without further requests, continue this insurance in force for a

period . . . .

The plaintiff conveniently divides that issue into five minor issues, to

wit:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

10. Cash and Paid-Up Insurance Values. At the end of the third

policy year or thereafter, upon the legal surrender of this Policy to the

Company while there is no default in premium payments or within two

months after the due date of the premium in default, the Company will

(1) grant a cash value as specified in Column (A) increased by the

cash value of any bonus additions and dividends left on accumulation,

which have been alloted to this Policy, less all indebtedness to the

Company on this Policy on the date of such surrender, or (2) endorse

this Policy as a Non-Participating Paid-up Policy for the amount as

specified in Column (B) of the Table of Guaranteed Values . . . .

"(a) Whether or not premium advances made by plaintiff-appellant

under the automatic premium loan clause of its policies are premiums

collected by the Company subject to tax;

11. Extended Insurance. After the premiums for three or more full

years have been paid hereunder in cash, if any subsequent premium is

not paid when due, and there is no indebtedness to the Company, on

the written request of the Insured . . . ."cralaw virtua1aw library

"(d) Whether the making of premium advances, granting for the sake

of argument that it amounted to collection of premiums, were done in

Toronto, Canada, or in the Philippines; and

From January 1, 1942 to December 31, 1946 for failure of the insured

under the above policies to pay the corresponding premiums for one or

more years, the plaintiffs head office at Toronto, applied the provisions

of the automatic premium loan clauses; and the net amount of

premiums so advanced or loaned totalled P1,069,254.98. On this sum

the defendant Collector of Internal Revenue assessed P17,917.12

which plaintiff paid supra protest . The assessment was made

pursuant to section 255 of the National Internal Revenue Code as

amended, which partly provides:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"SEC. 255. Taxes on insurance premiums. There shall be collected

from every person, company, or corporation (except purely cooperative

companies or associations) doing insurance business of any sort in the

Philippines a tax of one per centum of the total premiums collected . . .

whether such premiums are paid in money, notes, credits, or any

substitute for money but premiums refunded within six months after

payment on account of rejection of risk or returned for other reason to

person insured shall not be included in the taxable

receipts . . . ."cralaw virtua1aw library

It is the plaintiffs contention that when it made premium loans or

premium advances, as above stated, by virtue of the non-forfeiture

clauses, it did not collect premiums within the meaning of the above

sections of the law, and therefore it is not amenable to the tax therein

provided.

"(b) Whether or not, in the application of the automatic premium loan

clause of plaintiff-appellants policies, there is payment in money,

notes, credits, or any substitutes for money;

"(c) Whether or not the collection of the alleged deficiency premium

taxes constitutes double taxation;

"(e) Whether or not the fact that plaintiff-appellant was not doing

business in the Philippines during the period from January 1, 1942 to

September 30, 1945, inclusive, exempts it from payment of premium

taxes corresponding to said period."cralaw virtua1aw library

These points will be considered in their order. The first two may best

be taken up together in the light of a practical illustration offered by

appellant:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Suppose that A, 30 years of age, secures a 20-year endowment

policy for P5,000 from plaintiff-appellant Company and pays an annual

premium of P250.A pays the first ten yearly premiums amounting to

P2,500 and on this amount plaintiff-appellant pays the corresponding

taxes under section 255 of the National Internal Revenue Code.

Suppose also that the cash value of said policy after the payment of

the 10th annual premium amounts to P1,000." When on the eleventh

year the annual premium fell due and the insured remitted no money

within the months grace, the insurer treated the premium then over

due as paid from the cash value, the amount being a loan to the

policyholder (1) who could discharge it at any time with interest at 6

per cent. The insurance contract, therefore, continued in force for the

eleventh year.

Under the circumstances described, did the insurer collect the amount

of P250 as the annual premium for the eleventh year on the said

policy? The plaintiff says no; but the defendant and the lower court

say yes. The latter have, in our opinion, the correct view. In effect the

Manufacturers Life Insurance Co. loaned to "A" on the eleventh year,

the sum of P250 and the latter in turn paid with that sum the annual

premium on his policy. The Company therefore collected the premium

for the eleventh year.

"How could there be such a collection" plaintiff argues "when as a

result thereof, insurer becomes a creditor, acquires a lien on the policy

and is entitled to collect interest on the amount of the unpaid

premiums?"

Wittingly or unwittingly, the "premium" and the "loan" have been

interchanged in the argument. The insurer "became a creditor" of the

loan, but not of the premium that had already been paid. And it is

entitled to collect interest on the loan, not on the premium.

In other words, "A" paid the premium for the eleventh year; but in

turn he became a debtor of the company for the sum of P250. This

debt he could repay either by later remitting the money to the insurer

or by letting the cash value compensate for it. The debt may also be

deducted from the amount of the policy should "A" die thereafter

during the continuance of the policy.

Proceeding along the same line of argument counsel for plaintiff

observes "that there is no change, much less an increase, in the

amount of the assets of plaintiff-appellant after the application of the

automatic premium loan clause. Its assets remain exactly the same

after making the advances in question. It being so, there could have

been no collection of premium . . . ." We cannot assent to this view,

because there was an increase. There was the new credit for the

advances made. True, the plaintiff could not sue the insured to enforce

that credit. But it has means of satisfaction out of the cash surrender

value.

Here again it may be urged that if the credit is paid out of the cash

surrender value, there were no new funds added to the companys

assets. Cash surrender value "as applied to a life insurance policy, is

the amount of money the company agrees to pay to the holder of the

policy if he surrenders it and releases his claims upon it. The more

premiums the insured has paid the greater will be the surrender value;

but the surrender value is always a lesser sum than the total amount

of premiums paid." (Cyclopedia Law Dictionary 3d. ed. 1077.)

The cash value or cash surrender value is therefore an amount which

the insurance company holds in trust 2 for the insured to be delivered

to him upon demand. It is therefore a liability of the company to the

insured. Now then, when the companys credit for advances is paid out

of the cash value or cash surrender value, that value and the

companys liability is thereby diminished pro tanto. Consequently, the

net assets of the insurance company increased correspondingly; for it

is plain mathematics that the decrease of a persons liabilities means a

corresponding increase in his net assets.

Nevertheless let us grant for the nonce that the operation of the

automatic loan provision contributed no additional cash to the funds of

the insurer. Yet it must be admitted that the insurer agreed to consider

the premium paid on the strength of the automatic loan. The premium

was therefore paid by means of a "note" or "credit" or "other

substitute for money" and the tax is due because section 255 above

quoted levies taxes according to the total premiums collected by the

insurer "whether such premiums are paid in money, notes, credits or

any substitute for money.

In connection with the third issue, appellant refers to its example

about "A" who failed to pay the premium on the eleventh year and the

insurer advanced P250 from the cash value. Then it reasons out that

"if the amount of P250 is deducted from the cash value of P1,000 of

the policy, then taxing this P250 anew as premium collected, as was

done in the present case, will amount to double taxation since taxes

had already been collected on the cash value of P1,000 as part of the

P2,500 collected as premiums for the first ten years." The trouble with

the argument is that it assumes all advances are necessarily repaid

from the cash value. That is true in some cases. In others the insured

subsequently remits the money to repay the advance and to keep

unimpaired the cash reserve of his policy.

As a matter of fact of the total amount advanced (P1,069,254.98)

P158,666.63 had actually been repaid at the time of assessment

notice. Besides, the premiums paid and on which taxes had already

been collected, were those for the ten years. The tax demanded is on

the premium for the eleventh year.

In any event there is no constitutional prohibition against double

taxation.

On the fourth issue the appellant takes the position that as the

advances of premiums were made in Toronto, such premiums are

deemed to have been paid there not in the Philippines and

therefore those payments are not subject to local taxation. The thesis

overlooks the actual fact that the loans are made to policyholders in

the Philippines, who in turn pay therewith the premium to the insurer

thru the Manila branch. Approval of appellants position will enable

foreign insurers to evade the tax by contriving to require that premium

payments shall be made at their head offices. What is important, the

law does not contemplate premiums collected in the Philippines. It is

enough that the insurer is doing insurance business in the Philippines,

irrespective of the place of its organization or establishment.

not open for new business because its branch office was closed, still it

was practically and legally, operating in this country by collecting

premiums on its outstanding policies, incurring the risks and/or

enjoying the benefits consequent thereto, without having previously

taken any steps indicating withdrawal in good faith from this field of

economic activity (3).

This brings forth the appellants last contention that it was not

"engaged in business" in the Philippines during the years 1942 to

September 1945, and that as section 255 applies only to companies

"doing insurance business in the Philippines" this tax was improperly

demanded.

As a matter of fact, in objecting to the payment of the tax, plaintiffappellant never insisted, before the Bureau of Internal Revenue, that it

was not engaged in business in this country during those years.

It is our opinion that although during those years the appellant was

Wherefore, finding no prejudicial error in the appealed decision, we

hereby affirm it with costs.

You might also like

- Insurance Dispute Over Unpaid PremiumDocument3 pagesInsurance Dispute Over Unpaid PremiummansikiaboNo ratings yet

- Where There Is No Vision, The People Perish. Summit Guaranty V Arnaldo Page - 1Document2 pagesWhere There Is No Vision, The People Perish. Summit Guaranty V Arnaldo Page - 1Kenneth BuriNo ratings yet

- Manila Steamship Co Vs AbdulhamanDocument1 pageManila Steamship Co Vs AbdulhamanQue EnNo ratings yet

- Cir V Lincoln DigestDocument2 pagesCir V Lincoln DigestAlexa TinsayNo ratings yet

- Northwest V CuencaDocument2 pagesNorthwest V CuencaArrow PabionaNo ratings yet

- Crim procedure case law highlightsDocument28 pagesCrim procedure case law highlightsJon Meynard TavernerNo ratings yet

- Corporate Law Case Digest on Doing Business in the PhilippinesDocument1 pageCorporate Law Case Digest on Doing Business in the PhilippinesJosiah LimNo ratings yet

- 2 1 InsuranceDocument6 pages2 1 InsuranceLeo GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Common Carrier CASESDocument1 pageCommon Carrier CASESKa RenNo ratings yet

- Sunlife Assurance of Canada vs. CA GR No. 105135 June 22 1995Document4 pagesSunlife Assurance of Canada vs. CA GR No. 105135 June 22 1995wenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- 108 Tibay v. CA DigestDocument1 page108 Tibay v. CA DigestJovelan V. EscañoNo ratings yet

- 2nd Half Cases-Rulings OnlyDocument39 pages2nd Half Cases-Rulings OnlyalyssamaesanaNo ratings yet

- Rem Rev Cases Full TextDocument20 pagesRem Rev Cases Full TextaaronjerardNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument2 pagesCase Digestj guevarraNo ratings yet

- Insurance CasesDocument55 pagesInsurance CasesRyan RapaconNo ratings yet

- 48 Philippine American Life Insurance Co. v. PinedaDocument3 pages48 Philippine American Life Insurance Co. v. PinedaKaryl Eric BardelasNo ratings yet

- Insurance Law Review. 2016 Day 2Document178 pagesInsurance Law Review. 2016 Day 2jade123_129No ratings yet

- No Privity of Contract Between Repairmen and Insurer in Insured's AccidentDocument6 pagesNo Privity of Contract Between Repairmen and Insurer in Insured's AccidentADNo ratings yet

- Yu Pang Cheng vs. CADocument1 pageYu Pang Cheng vs. CAJohn Mark RevillaNo ratings yet

- February - June 2019 (Crim Digest)Document6 pagesFebruary - June 2019 (Crim Digest)Concon FabricanteNo ratings yet

- Interpretation: Insurance Law Midterms Reviewer Sunny & Chinita NotesDocument33 pagesInterpretation: Insurance Law Midterms Reviewer Sunny & Chinita NotesHezekiah JoshuaNo ratings yet

- Insular Life Ordered to Pay Claims and Fine for Violating Insurance CodeDocument8 pagesInsular Life Ordered to Pay Claims and Fine for Violating Insurance CodePatrice ThiamNo ratings yet

- Atlas V CIRDocument1 pageAtlas V CIRBrylle Garnet DanielNo ratings yet

- 15 Caltex (Philippines), Inc. vs. Sulpicio Lines, Inc., 315 SCRA 709Document17 pages15 Caltex (Philippines), Inc. vs. Sulpicio Lines, Inc., 315 SCRA 709blessaraynesNo ratings yet

- Director of Land v. IAC, 146 SCRA 509 (1986)Document39 pagesDirector of Land v. IAC, 146 SCRA 509 (1986)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Agency Partnership and Trust. NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNDocument13 pagesCase Digest Agency Partnership and Trust. NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNChristian FernandezNo ratings yet

- 8 Pilipinas Bank Vs CA PDFDocument3 pages8 Pilipinas Bank Vs CA PDFNicoleAngeliqueNo ratings yet

- Syllabus BO1 August 2019 ATAP0Document134 pagesSyllabus BO1 August 2019 ATAP0Anna WarenNo ratings yet

- Lease clause assigning insurance proceeds without consent voidDocument2 pagesLease clause assigning insurance proceeds without consent voidmar corNo ratings yet

- 02 Country Bankers Insurance Corporation vs. Lianga Bay and Community Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc.Document16 pages02 Country Bankers Insurance Corporation vs. Lianga Bay and Community Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc.ATR100% (1)

- American Home Assurance Co. v. Chua, 1999Document2 pagesAmerican Home Assurance Co. v. Chua, 1999Randy SiosonNo ratings yet

- 7 Compania Maritima V Insurance Co of NADocument1 page7 Compania Maritima V Insurance Co of NAJovelan V. EscañoNo ratings yet

- 2 Matute v. Court of AppealsDocument31 pages2 Matute v. Court of AppealsMary Licel RegalaNo ratings yet

- Filipina Migrant Worker's Death Ruled HomicideDocument9 pagesFilipina Migrant Worker's Death Ruled HomicideJenniferPizarrasCadiz-CarullaNo ratings yet

- Biagtan vs. The Insular Life Assurance Co., LTD., (44 SCRA 58)Document2 pagesBiagtan vs. The Insular Life Assurance Co., LTD., (44 SCRA 58)Thoughts and More ThoughtsNo ratings yet

- Soncuya Vs de LunaDocument1 pageSoncuya Vs de LunaVikki Mae AmorioNo ratings yet

- Insurance 2 - Ong - RCBC V CADocument2 pagesInsurance 2 - Ong - RCBC V CADaniel OngNo ratings yet

- Life vs. Property Insurance; Assignments and Total LossesDocument3 pagesLife vs. Property Insurance; Assignments and Total LossesFelix C. JAGOLINO IIINo ratings yet

- People v. Romualdez, G.R. No. 166510, 23 July 2008Document27 pagesPeople v. Romualdez, G.R. No. 166510, 23 July 2008JURIS UMAKNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Makati Tuscany Condominium Corporation vs. Court of Appeals (GR 95546, 6 November 1992)Document2 pagesFacts:: Makati Tuscany Condominium Corporation vs. Court of Appeals (GR 95546, 6 November 1992)Mary LouiseNo ratings yet

- Case 12Document3 pagesCase 12April CaringalNo ratings yet

- Prudential Guarantee and Assurance Inc., vs. Trans-Asia Shipping Lines Inc, G.R. No. 151890 June 20, 2006 (Full Text and Digest)Document14 pagesPrudential Guarantee and Assurance Inc., vs. Trans-Asia Shipping Lines Inc, G.R. No. 151890 June 20, 2006 (Full Text and Digest)RhoddickMagrataNo ratings yet

- Cesar Issac vs. A.L. Ammen TransportationDocument1 pageCesar Issac vs. A.L. Ammen TransportationEarl LarroderNo ratings yet

- Agency CasesDocument271 pagesAgency CasesGerardChanNo ratings yet

- 11-14 EvidDocument90 pages11-14 Evidione salveronNo ratings yet

- 129-Atienza vs. Philimare Shipping & Eqpt. SupplyDocument3 pages129-Atienza vs. Philimare Shipping & Eqpt. SupplyNimpa PichayNo ratings yet

- PNB V. Picornell FACTS: Bartolome Picornell, Following Instruction Hyndman, Tavera &Document6 pagesPNB V. Picornell FACTS: Bartolome Picornell, Following Instruction Hyndman, Tavera &Tom Lui EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Appellee vs. vs. Appellant: Second DivisionDocument13 pagesAppellee vs. vs. Appellant: Second DivisionMara VNo ratings yet

- Zalamea v. C.A: Overbooking Amounts to Bad FaithDocument2 pagesZalamea v. C.A: Overbooking Amounts to Bad Faithbenjo2001No ratings yet

- Personal Liability of Corporate Officers Under Trust ReceiptsDocument7 pagesPersonal Liability of Corporate Officers Under Trust ReceiptsTrem GallenteNo ratings yet

- 27 Geagonia vs. CADocument13 pages27 Geagonia vs. CAMichelle Montenegro - AraujoNo ratings yet

- 065 Saturnino Vs PhilAm Life - DIGESTDocument2 pages065 Saturnino Vs PhilAm Life - DIGESTD De LeonNo ratings yet

- Casis Agency Full Text CompilationDocument903 pagesCasis Agency Full Text CompilationBer Sib JosNo ratings yet

- Insurance Double Policy Ruled VoidDocument1 pageInsurance Double Policy Ruled VoidN.SantosNo ratings yet

- Artex v. Wellington - JasperDocument1 pageArtex v. Wellington - JasperJames LouNo ratings yet

- PATCaseDigests31 40Document7 pagesPATCaseDigests31 40ZariCharisamorV.ZapatosNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Ildelfonso CoscolluelaDocument1 pageHeirs of Ildelfonso CoscolluelaMaricar Corina CanayaNo ratings yet

- Insurance Code: P.D. 612 R.A. 10607 Atty. Jobert O. Rillera, CPA, REB, READocument85 pagesInsurance Code: P.D. 612 R.A. 10607 Atty. Jobert O. Rillera, CPA, REB, REAChing ApostolNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. Servier Philippines G.R. No.166377Document9 pagesSantos vs. Servier Philippines G.R. No.166377Rea Nina OcfemiaNo ratings yet

- Manufacturers Life Insurance v. MeerDocument4 pagesManufacturers Life Insurance v. MeerErnie GultianoNo ratings yet

- REMEDIAL - People Vs GSIS - 60 Days Limitation PeriodDocument16 pagesREMEDIAL - People Vs GSIS - 60 Days Limitation PeriodAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- REMEDIAL - Citytrust Banking Corp Vs Cruz - DamagesDocument5 pagesREMEDIAL - Citytrust Banking Corp Vs Cruz - DamagesAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Remedial - City Government of Butuan Vs Cbs - InhibitionDocument15 pagesRemedial - City Government of Butuan Vs Cbs - InhibitionAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Balatbat Vs AriasDocument5 pagesBalatbat Vs AriasAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Lantion Vs NLRCDocument6 pagesLantion Vs NLRCPaulo Miguel GernaleNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules on land ownership disputeDocument14 pagesSupreme Court rules on land ownership disputeAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Spouses Ricardo and Evelyn Marcelo Vs Judge Domingo PichayDocument2 pagesSpouses Ricardo and Evelyn Marcelo Vs Judge Domingo PichayAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- BM 730Document3 pagesBM 730Alandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- CHR Director's suspensionDocument12 pagesCHR Director's suspensionAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Lawyer's petition to resume practice granted with conditionsDocument3 pagesLawyer's petition to resume practice granted with conditionsAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- ACME Vs CADocument3 pagesACME Vs CAAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Brunet Vs GuarenDocument2 pagesBrunet Vs GuarenAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- 70 Apex Mining Corp Vs NLRCDocument6 pages70 Apex Mining Corp Vs NLRCRay Carlo Ybiosa AntonioNo ratings yet

- 04 Luz Farms Vs DAR SecretaryDocument10 pages04 Luz Farms Vs DAR SecretaryDraei DumalantaNo ratings yet

- Ang Giok Chip v. Springfield Fire & Marine Ins Co ruling on warranty riderDocument3 pagesAng Giok Chip v. Springfield Fire & Marine Ins Co ruling on warranty riderAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- PAO Vs SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesPAO Vs SandiganbayanAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Tibay Vs CADocument5 pagesTibay Vs CAAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- American Vs TantucoDocument4 pagesAmerican Vs TantucoAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Abaqueta Vs FloridoDocument3 pagesAbaqueta Vs FloridoAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Apodaca V NLRCDocument2 pagesApodaca V NLRCAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- YrasueguiDocument28 pagesYrasueguiAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Cuajao V Lo TanDocument2 pagesCuajao V Lo TanAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Kmu VS DirDocument3 pagesKmu VS DirAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Mercado Vs Security BankDocument5 pagesMercado Vs Security BankAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Amendments to Republic Act No. 790 Granting Radio Station PermitDocument1 pageAmendments to Republic Act No. 790 Granting Radio Station PermitAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- People Vs Guevarra CaseDocument8 pagesPeople Vs Guevarra CaseAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Gamalinda Vs FernandoDocument2 pagesGamalinda Vs FernandoAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Casco V GimenezDocument3 pagesCasco V GimenezAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- 14 Us V FowlerDocument3 pages14 Us V FowlerAlandia GaspiNo ratings yet

- Sample Detailed EvaluationDocument5 pagesSample Detailed Evaluationits4krishna3776No ratings yet

- Hume's Standard TasteDocument15 pagesHume's Standard TasteAli Majid HameedNo ratings yet

- UNIMED Past Questions-1Document6 pagesUNIMED Past Questions-1snazzyNo ratings yet

- Food and ReligionDocument8 pagesFood and ReligionAniket ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Accounting What The Numbers Mean 11th Edition Marshall Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesAccounting What The Numbers Mean 11th Edition Marshall Solutions Manual 1amandawilkinsijckmdtxez100% (23)

- Hbo Chapter 6 Theories of MotivationDocument29 pagesHbo Chapter 6 Theories of MotivationJannelle SalacNo ratings yet

- HM5 - ScriptDocument4 pagesHM5 - ScriptCamilleTizonNo ratings yet

- Coasts Case Studies PDFDocument13 pagesCoasts Case Studies PDFMelanie HarveyNo ratings yet

- Instant Ear Thermometer: Instruction ManualDocument64 pagesInstant Ear Thermometer: Instruction Manualrene_arevalo690% (1)

- Genocide/Politicides, 1954-1998 - State Failure Problem SetDocument9 pagesGenocide/Politicides, 1954-1998 - State Failure Problem SetSean KimNo ratings yet

- English FinalDocument321 pagesEnglish FinalManuel Campos GuimeraNo ratings yet

- FOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD StatementDocument4 pagesFOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD Statementlesly malebrancheNo ratings yet

- A Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesDocument7 pagesA Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesRaja ChandruNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in Special ProceedingsDocument42 pagesCase Digest in Special ProceedingsGuiller MagsumbolNo ratings yet

- Block 2 MVA 026Document48 pagesBlock 2 MVA 026abhilash govind mishraNo ratings yet

- BOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Document4 pagesBOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Eric FuentesNo ratings yet

- 14 Worst Breakfast FoodsDocument31 pages14 Worst Breakfast Foodscora4eva5699100% (1)

- Marylebone Construction UpdateDocument2 pagesMarylebone Construction UpdatePedro SousaNo ratings yet

- Voiceless Alveolar Affricate TsDocument78 pagesVoiceless Alveolar Affricate TsZomiLinguisticsNo ratings yet

- Feminism in Lucia SartoriDocument41 pagesFeminism in Lucia SartoriRaraNo ratings yet

- Bhojpuri PDFDocument15 pagesBhojpuri PDFbestmadeeasy50% (2)

- CVA: Health Education PlanDocument4 pagesCVA: Health Education Plandanluki100% (3)

- The Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerDocument33 pagesThe Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerBeto TNo ratings yet

- Symbian Os-Seminar ReportDocument20 pagesSymbian Os-Seminar Reportitsmemonu100% (1)

- Characteristics and Elements of A Business Letter Characteristics of A Business LetterDocument3 pagesCharacteristics and Elements of A Business Letter Characteristics of A Business LetterPamela Galang100% (1)

- Perilaku Ramah Lingkungan Peserta Didik Sma Di Kota BandungDocument11 pagesPerilaku Ramah Lingkungan Peserta Didik Sma Di Kota Bandungnurulhafizhah01No ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishDocument16 pagesCambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishJonathan ChuNo ratings yet

- AC & Crew Lists 881st 5-18-11Document43 pagesAC & Crew Lists 881st 5-18-11ywbh100% (2)

- Industrial and Organizational PsychologyDocument21 pagesIndustrial and Organizational PsychologyCris Ben Bardoquillo100% (1)

- Powerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterDocument24 pagesPowerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterJiya Nitric AcidNo ratings yet