Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fatal Leptopsirosis Case

Uploaded by

Fariz NurOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fatal Leptopsirosis Case

Uploaded by

Fariz NurCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2013, 3, 12-17

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojmm.2013.31003 Published Online March 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojmm)

Fatal Leptospirosis Case in Pediatric Patient:

Clinical Case

Laura I. Santiago Garca1, Citlalli Martnez Cruz1, Irma Zamudio Lugo2,

Beatriz Rivas Snchez3, Oscar Velasco Castrejn3, Joel Navarrete Espinosa1*

1

Coordination of Epidemiologic Surveillance, Unit of Public Health, IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico

Division of Hospital Epidemiologic, Childrens Hospital, CMN Century XXI, IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico

3

Clinic of Tropical Medicine, Unit of Experimental Medicine, School of Medicine, UNAM, Mexico

Email: *joel.navarrete@imss.gob.mx

Received December 6, 2012; revised January 11, 2013; accepted January 31, 2013

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Leptospirosis is a worldwide zoonosis. It is transmitted through the urine of infected animals. Currently,

there is an increase of reports in many countries. In humans, it presents an ample clinical spectrum, which goes from an

asymptomatic infection up to Weil syndrome, which is generally fatal. Clinical Case: A male, 6 years of age, who

started with onset fever and jaundice, handled in private means, diagnosed as viral hepatitis A and was referred to an

institutional hospital where hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were detected. His evolution was towards graveness and,

therefore, he was referred to a third level hospital with reactive Hepatitis diagnosis and to rule out lymphoma. On admission, he presented liver and kidney failure, as well as metabolic acidosis and pulmonary haemorrhage that led to

death 6 hours later. Confirmatory tests for hepatitis were negative; biopsies were taken post-mortem for Leptospira diagnosis, which were positive in liver and kidney. Conclusions: Leptospirosis is a disease that may be manifested in

multiple ways. It is important the understanding of this disease by the physician to improve the diagnosis and, for general population, to avoid exposure. The examination of the epidemiological history of the patient is essential.

Keywords: Leptospirosis; Fatal; Pediatric; Mxico

1. Introduction

Leptospirosis is considered a cosmopolitan zoonosis that

is present in both rural and urbanized areas, where environmental factors conjugate (weather, geographical area,

rivers, rain, etc.) and life styles (close relations with animals) promote their development [1]. Studies performed

by the International Society of Leptospirosis estimate

that each year around half million cases (severe cases) of

this disease are reported worldwide [2]. In Mexico, leptospirosis incidence is not exactly known because there is

not existing a specific surveillance system and only some

cases reported in some entities of the country are considered. However, studies performed in different populations with different techniques report prevalence that go

from 10% up to 63% in the affected population [3-6].

Leptospira is a fine bacterium, 6 to 20 m length,

flexible helical, with extremities as hooks, strictly aerobic, and extremely mobile; it may survive in water, alkaline soil, humid and warm environments. 250 serovares

are known, grouped into 24 serogroups. This bacterium

may remain for long periods in the renal tubules of ap*

Corresponding author.

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

parently healthy animals, being excreted in the urine for

many years, becoming asymptomatic carriers and favouring transmission from animal to animal or from animal to

human [1,2,7].

Humans are infected in a direct form (less frequent) by

the contact of urine and tissue from infected animals

through injured skin, especially feet or nasal and oral

mucosa, or conjunctiva, and an indirect form (epidemic

breakouts) through contact of stagnant water, dirt, or

food contaminated with Leptospira [1].

After an incubation period of 5 to 14 days, the infection may be asymptomatic or may be manifested in an

acute form, and/or become chronic. In its acute form,

symptoms may be undifferentiated or mild, or present a

serious condition known as Weil Syndrome, characterized by liver and kidney failure which commonly lead to

death [7]. The chronic form of the infection has been

known only since few years ago and it may present a

large diversity of clinical manifestations, affecting, in the

same way, different organs [8,9].

The lack of knowledge of the disease, its clinical behaviour and its transmission have conditioned the under

registration of the infection, and, even worse, determines

OJMM

L. I. S. GARCA ET AL.

an inadequate treatment, which redounds in the increase

of complications and lethality. This is especially true

when we consider child population and diseases such as

viral hepatitis, which presents an initial clinical frame

very similar to acute leptospirosis [10,11].

The case of a pediatric patient who sought attention

presenting a symptoms characterized by fever, jaundice,

and hepatitis, who presented a torpid evolution that after

seven days led to his death is presented. The purpose of

the divulging of this information is to better the diagnosis

and treatment of patients seeking medical attention due

to these causes.

2. Clinical Case

A 6-year-old male, living in the city of Queretaro, Queretaro, Mexico, from a medium socio-economic stratum.

2.1. Family Background

Father, 63 years of age, with a post-degree, writer;

mother, 31 years of age, finished high school, housewife.

Both parents apparently healthy and living in free union.

He has three siblings, 4, 3, and 1 year of age, apparently

healthy.

2.2. Pediatric-Clinical Background

He was a first-time, high risk pregnancy product; with

miscarriage threat in the fourth month. The product was

obtained by eutocic delivery at 39 weeks gestation,

weighing 2250 g, 47 cm height, and 8/9 Apgar. He was

breast-fed for 6 months, and then combined with formula

until one year and a half of age, being weaned at 4

months of age. At the age of four months he was hospitalized due to a rotavirus infection. Immunization schedule was complete for his age. Blood type A (-).

2.3. Current Condition

Clinical condition starts on 29/05/2011 with general malaise.

On 01/06/2012 he presents fever higher to 39C without schedule predominance, bilateral cervical lymph

adenopathy, approximately 1 cm, hard consistency and

painful on palpation, he also presented abdominal pain.

At that time he was managed with antipyretic (nimesulide) without an apparent improvement.

Two days later conjunctival jaundice, dark urine, and

acolia appear, so he is taken to a private doctor who

gives a diagnosis of viral hepatitis A and asks for laboratory tests which demonstrate alteration in liver function

(Table 1) and turn positive to antibody-anti-hepatitis A:

IgM and IgG (private laboratory). That same day it is

decided to take him to a second-level institutional hospital in the city of Quertaro, where he is admitted with

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

13

diagnoses of moderate dehydration, viral hepatitis in

study to rule out bicytopenia and lymphoma. On admission, he presented Kramer IV jaundice, bilateral cervical

lymphadenopathy 3 2 cm, mobile and tender to palpation, abdomen with hepatomegaly 3 cm, and mild splenomegaly.

During his hospital stay, platelet units were transfused,

as well as freshly frozen plasma. The abdominal ultrasound performed 4/06/2011 showed moderate hepatomegaly and splenomegaly; the performed serology performed in the hospital against hepatitis A, B, C, and Core

was negative, as well as other studies performed for

rubella, CMV (Cytomegalovirus), toxoplasmosis, coxsackie, Epstein Barr, herpes, and ECHO (enteric cytopathic human virus)

Due to the fast evolution towards graveness, on 5/06/

2011 he was transferred to a third-level hospital in Mexico City, where he was admitted to the ICU (Intensive

Care Unit).

On physical examination, hyperemic pharynx with

greenish postnasal discharge was found, plus submandibular lymphadenopath of approximately 1 cm, fixed to

plans and painful on palpation, the abdomen was soft,

depressible, with decreased peristalisis, and hemapatology and splenomegaly of 3 cm bellow the costal margin.

He required tracheal intubation and central venous catheter.

Six hours after admission in the service, he presented

metabolic acidosis episodes, pulmonary hemorrhage

bleeding visible through the cannula, thus increasing the

ventilation cycles. Chest X-rays presented effacement of

the cost right diaphragmatic angle, suggesting pleural

effusion.

On 06/06/2011 he presented torpid evolution with a

decrease in blood pressure, unresponsive to vasopressors

(dopamine), so he was handled with catecholamines

(adrenaline), showing minimum response. Neurologically, the patient was at that time under barbiturateinduced coma. Hours later, heavy bleeding occurred via

nasogastric tube and irreversible cardiac arrest occurred,

leading to the childs death.

Due to the fact that the tests performed for hepatitis

and other possible agents were negative, post-mortem

samples were taken for the diagnosis of leptospirosis,

which were processed in the laboratory of the Laboratorio de la Clnica de Medicina Tropical from the

Unidad de Medicina Experimental at the Medicine

Faculty from the Universidad Nacional Autnoma de

Mxico. Leptospira search was performed with silver

staining of biopsies by Warthin Starry stain, which resulted positive in liver (Figures 1 and 2) and kidney

(Figures 3 and 4), and negative in lymph node. In addition, diagnosis tests were performed to the patients

siblings, which also yielded positive results.

OJMM

L. I. S. GARCA ET AL.

14

Table 1. Laboratory tests performed to the patient according to the attending place.

Particular

2nd Level Hospital

3rd Level Hospital

Date

1.06.2011

2.06.2011

3.06.2011

5.06.2011

6.06.2011

Days of Evolution

Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

Day 7

Day 8

11.3

10.6

CBC

Hemoglobin

14

13.9

12.10

Hematocrit

41

40.4

33.40

Leucocytes

1000

920

1670

Lymphocytes

67

44.8

33

Neutrophiles

42.1

57.70

Eosinophils

0.1

0.2

2.240

19.000

Platelets

30

2200

3000

38.5

59.4

46.7

4.520

30.000

59.000

96

73

111

13

MCV

Blood Chemistry

75

Glucose

Urea

147

65

84

Creatinine

Uric Acid

12.6

Cholesterol

85

82

Triglycerides

304

365

Bilirrubinas

Total Bilirubin

10.5

10.9

14.45

16.95

Direct Bilirubin

8.1

9.7

10.97

12.24

Indirect Bilirubin

2.4

2.5

3.98

4.71

Liver Function Tests

ALT

1145

1408

3010

2410

2106

AST

2571

4154

7550

11460

9976

LDH

3781

1211

Phosphoquinase

161

193

120

98

Alkaline Phosphatase

Serum Electorlytes

Calcium

7.6

6.5

6.5

Sodium

127

133

136

Potasium

5.20

4.90

4.4

Chlorine

100

98

99

Phosphorus

4.4

6.6

Magnesium

Hepatitis Serology

Antibodies

IgM

Positive

IgG

Negative

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

Negative

OJMM

L. I. S. GARCA ET AL.

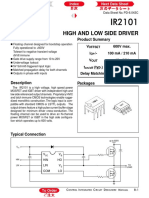

Figure 1. Leptospira in liver cut.

15

Figure 4. Leptospira in kidney cut.

3. Discussion

Figure 2. Leptospira in liver cut.

Figure 3. Leptospira in kidney cut.

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

In the last decades, leptosirosis has become quite important for it has been recognized that the disease may turn

acute, self-limited, or fatal, presenting a pulmonary hemorrhage or turn into chronic, being able of manifestation

in multiple ways [8,9,12]

Even more, the knowledge of its transmission mechanism has allowed recognizing that the infection is not any

more a professional disease, and it is now known that the

exposure may be from the contact with infected domestic

animals (dogs, cows, pigs) and wild fauna (rats), as well

as with water pollutes with urine of these animals, especially when recreation activities, such as swimming, are

performed or as a consequence of secondary flooding

due to heavy rains; another mechanism that has been

described is bad hygiene habits, such as the intake of

canned food without cleaning it first [13-15].

In this sense, it is more often heard of cases initially

diagnosed with several different diseases, and only after

several studies they were then diagnosed as leptospirosis [10,16]. These facts would be unimportant if the disease were self-limited and innocuous; however, leptospirosis is an infection that entails a high risk of death if

it is not timely diagnosed and treated.

Not knowing the disease and its clinical behaviour, as

well as the factors that condition it, causes the doctor not

to think in this possible diagnosis first, which worsens

when the evolution of the disease is fast and non-specific,

as in the present case in which the patient died before

reaching a diagnosis.

From a medical and epidemiologic point of view, if it

is true that an under registration of the infection is suspected, it is also true that leptospirosis may behave in

multiple ways and may be mixed up with many diseases

(Table 2), which translates in a handicap for the doctor

OJMM

L. I. S. GARCA ET AL.

16

when performing the diagnosis, implying a risk for the

evolution of the patient.

According to the above, the epidemiologic research of

these patients may be of great help to diagnose the disease correctly. In the reported case, there were data that

should have been key for the diagnosis of the disease,

among them, knowing the antecedent of being in contact

with water in a swimming pool that did not met the necessary hygiene conditions previous to the initial clinical

manifestation, as well as living closely with three dogs;

these data were important, especially when the confirmatory studies for infectious Hepatitis performed in the

hospital turned out negative and there was no previous

antecedent of contact with similar cases that could lead to

an outbreak of this viral infection. In this sense, the study

of this disease is important to establish which factors

determine an individual to get sick. It is noteworthy that

in this case, only one of the three infected brothers

suffered a severe condition, which could be related,

among other factors, to the individuals immune mechanisms.

All this highlights the importance of the spreading of

this information to lead the medical doctor towards this

diagnosis and in this way offer a better expectation to the

patient. Never the less, it is not to think in this infection

early, it is necessary the implementation of laboratory

tests that allow us identify on time the bacterium to be

able to treat the patient correctly, especially with clinical

data and laboratory parameter do not make evident great

differences that aid in the diagnosis (Table 3). According

to all the above, it is not redundant to mention the need to

start the use of antibiotics in the first days of evolution of

this infection to avoid its evolution towards graveness,

justifying their use at the mere suspicion of the infection.

Table 2. Differential leptospirosis diagnosis.

Acute Leptospirosis

Chronic Leptospirosis

Influenza

Dengue and hemorrhagic dengue

Hantavirus infections, including hantavirus pulmonary syndrome or other respiratory distress syndromes

Yellow fever and other viral hemorrhagic fevers

Rickettsioses

Borreliosis

Malaria

Typhoid and other enteric fevers

Viral hepatitis

Fever of unknown origin (FUO)

Toxoplasmosis.

Uveitis

Iridiociclitis

CNS alterations

Myelo-proliferative

Table 3. Comparison of laboratory parameters, normal values, hepatites A and patient with leptospirosis.

Laboratory Studies

Reference

Hepatitis A

Pacient

Liver Function

Direct Bilirrubin

0.0 - 0.456 mg/dL

5 - 6 mg/dL

>25 mg/dL (cholestatic hepatitis)

12.24 mg/dL

Transaminase Alanine Transferase

1 - 30 mU/ml

5 - 10 times the normal value

3010 mU/ml

Alkaline Phosphatase

190 - 490 mU/ml

>3 times the normal range

491mU/ml

CBC

Leucocytes

4000 - 11,000 mm

Incremento

16,700 mm3

Limphocytes

35% - 45%

Incremento

38.5 %

Neutrophiles

40% - 50%

Incremento

46.7%

Hemoglobine

10 - 14

14

s/d

Hematocrite

35 - 45

s/d

41

Plateletes

200,000 - 300,000

s/d*

19,000 - 59,000

No data.

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

OJMM

L. I. S. GARCA ET AL.

Leptospirosis is an ailment that is originated by the

close relation with domestic infected animals or water

contaminated with their urine; thus, exposure and infection rate of our population could be very high, which

implies the intentional search for the infection in all those

patients with fever and hepatitis-like data, hemorrhages,

acute kidney failure, which do not fall in a specific diagnosis.

Education and promotion are important for the general

populations health to avoid these risks factor that could

be fatal. In the same way, the magnitude and importance

of this disease justifies thinking in reinforcing a formal

epidemiological surveillance for leptospirosis in Mexico,

to really measure its magnitude and offer the necessary

elements in taking decision in prevention and zoonosis

control.

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

A. R. Bharti, J. E. Nally, J. N. Ricaldi, M. A. Matthias, M.

M. Diaz, M. A. Lovett, et al., Leptospirosis: A Zoonotic

Disease of Global Importance, Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol. 3, No. 12, 2003, pp. 757-771.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00830-2

R. A. Hartskeerl, International Leptospirosis Society:

Objetives and Achievements, Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2005, pp. 7-10.

I. A. Vado-Sols, M. A. Crdenas-Marrufo, H. LaviadaMolina, F. Vargas-Puerto, J. E. B. Jimnez-Delgadillo y

Zavala-Velzquez, Estudio de Casos Clnicos e Incidencia de Leptospirosis Humana en el Estado de Yucatn,

Mxico Durante el Periodo de 1998-2000, Revista

Biomdica, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2002, pp. 157-164.

C. B. Leal-Castellanos, R. Garca-Surez, E. GonzlezFigueroa, J. L. Fuentes-Allen and J. Escobedo-De la Pea

Risk Factors and the Prevalence of Leptospirosis Infection in a Rural Community of Chiapas, Mxico,

Epidemiol Infect, Vol. 131, No. 3, 2003, pp. 1149-1156.

doi:10.1017/S0950268803001201

[5]

N. E. Joel, M. M. Maribel, R. S. Beatriz and V. C. Oscar,

Leptospirosis Prevalence in a Population of Yucatan,

Mexico, Journal of Pathogens, Vol. 2011, 2011, Article

ID: 408604.

[6]

G. Varela and V. J. Zavala, Estudio Serolgico de la

Leptospirosis en la Repblica Mexicana, Revista del

Instituto de Salubridad y Enfermedades Tropicales, Vol.

21, 1961, pp. 49-52.

Copyright 2013 SciRes.

17

[7]

P. N. Levett, Leptospirosis, In: Mandell, Douglas and

Bennetts, Eds, Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th Edition, Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2005,

pp. 2789-2795.

[8]

O. Velasco-Castrejn, B. Rivas-Snchez and H. H. RiveraReyes, Leptospirosis Humana Crnica, In: J. NarroRobles, O. Rivero-Serrano and J. J. Lpez Brcena, Eds.,

Diagnstico y Tratamiento en la Prctica Mdica, 2nd

Edition, Manual Moderno, Mxico, 2006, pp. 641-650.

[9]

C. O. Velasco, S. B. Rivas, J. Espinoza, J. Jimnez and E.

Ruiz, Enfermedades Simuladas y Acompaantes de Leptospirosis, Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical, Vol.

57, No. 1, 2005, pp. 75-76

[10] M. S. Hernndez, G. R. Menndez, O. M. Torres, J. L. M.

Alonso and J. M. A. Snchez, Leptospirosis en Nios de

una Provincia Cubana, Revista Mexicana de Pediatra,

Vol. 73, No. 1, 2006, pp. 14-17.

[11] S. J. Prez, O. J. Colin, S. A. Caballero and E. A. Cuellar,

Seropositividad a Leptospiras de Pacientes Sospechosos

de Hepatitis Viral Negativos a Marcadores Serolgicos,

Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical, Vol. 57, No. 1,

2005, pp. 57-58.

[12] R. T. Trevejo, P. J. G. Rigau, D. A. Ashford, E. M. McClure, G. C. Jarquin, J. J. Amador, et al., Epidemic Leptospirosis Associated with Pulmonary Hemorrhage-Nicaragua 1995, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol.

178, No. 5, 1998, pp. 1457-1463. doi:10.1086/314424

[13] C. Manuel, T. Rafael, B. Lourdes, G. Dana, G. Martha

and V. J. M. Brote de, Leptospirosis Asociado a la

Natacin en una Fuente de Agua Subterrnea en Una

Zona Costera, Lima-Per, Revista Peruana de Medicina

Experimental y Salud Pblica, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2009, pp.

441-448.

[14] J. Pradutkanchana, S. Pradutkanchana, M. Kemapanmanus,

N. Wuthipum and Silpapajakul, The Etiology of Acute

Pirexia of Unknown Origin in Children after a Flood,

The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and

Public Health, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2003, pp. 175-178.

[15] E. J. Sanders, J. G. Rigau-Perez, H. L. Smits, C. C. Deseda, V. A. Vorndam, T. Aye, et al.. Increase of Leptospirosis in Dengue Negative Patients after a Hurricane in

Puerto Rico in 1966, The American Journal of Tropical

Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 61, No. 3, 1999, pp. 399404.

[16] O. Velasco-Castrejn, B. Rivas-Snchez, E. Gutirrez, L.

Chvez, P. Duarte, S. Chavarra, et al., Leptospira Simulador o Causante de Leucemia? Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2005, pp. 17-24.

OJMM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TMDocument144 pagesThe Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TM:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El100% (5)

- Abdomen - FRCEM SuccessDocument275 pagesAbdomen - FRCEM SuccessAbin ThomasNo ratings yet

- Internal Audit ChecklistDocument18 pagesInternal Audit ChecklistAkhilesh Kumar75% (4)

- Respiratory Tract InfectionDocument13 pagesRespiratory Tract InfectionFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Antinuclear Antibodies: When To Test and How To Interpret FindingsDocument4 pagesAntinuclear Antibodies: When To Test and How To Interpret FindingsFariz NurNo ratings yet

- 2015 AHA Guidelines Highlights EnglishDocument36 pages2015 AHA Guidelines Highlights EnglishshiloinNo ratings yet

- (Kasus-Endokrin) (2016!11!10) A Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State in A Patient With Pulmonary Tuberculosis (Ismayadi)Document11 pages(Kasus-Endokrin) (2016!11!10) A Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State in A Patient With Pulmonary Tuberculosis (Ismayadi)Fariz NurNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Prevention, Care And... Ic Hepatitis B PDFDocument16 pagesGuidelines For The Prevention, Care And... Ic Hepatitis B PDFFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Frailty, John E. MorleyDocument11 pagesFrailty, John E. MorleyFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Ana TestDocument4 pagesAna TestFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of AKI BasileDocument99 pagesPathophysiology of AKI BasileFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Activation of The Coagulation Cascade in Patients With LeptospirosisDocument7 pagesActivation of The Coagulation Cascade in Patients With LeptospirosisFariz NurNo ratings yet

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Absolute Neutrophil CountDocument5 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Absolute Neutrophil CountFariz NurNo ratings yet

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki Absolute Neutrophil CountDocument5 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki Absolute Neutrophil CountFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Tract InfectionDocument13 pagesRespiratory Tract InfectionFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Di, Siadh, CSWDocument17 pagesDi, Siadh, CSWVanitha Ratha KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Di, Siadh, CSWDocument17 pagesDi, Siadh, CSWVanitha Ratha KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Ethionamide-Induced Hypothyroidism in ChildrenDocument3 pagesEthionamide-Induced Hypothyroidism in ChildrenFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Ethionamide-Induced Hypothyroidism in ChildrenDocument3 pagesEthionamide-Induced Hypothyroidism in ChildrenFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Neutrophil GranulocyteDocument16 pagesNeutrophil GranulocyteFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Ptre HT and MortalitasDocument15 pagesPtre HT and MortalitasFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Insiden RematologiDocument11 pagesInsiden RematologiFariz NurNo ratings yet

- H.pylori Dan CA GasterDocument32 pagesH.pylori Dan CA GasterFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Steroid Lupus NefritisDocument3 pagesSteroid Lupus NefritisFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Epidemiology SleDocument12 pagesUnderstanding The Epidemiology SleFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Ajg 1998292 ADocument9 pagesAjg 1998292 AFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Bacterial factors and host immune responses in H pylori infectionDocument5 pagesBacterial factors and host immune responses in H pylori infectionFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Death Fariz 2-1-14Document5 pagesDeath Fariz 2-1-14Fariz NurNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter Pylori Eradication: Changes in Gastric Acid Secretion Assayed by Endoscopic Gastrin Test Before and AfterDocument7 pagesHelicobacter Pylori Eradication: Changes in Gastric Acid Secretion Assayed by Endoscopic Gastrin Test Before and AfterFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With ParadoxicalDocument11 pagesFactors Associated With ParadoxicalFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: ReferenceDocument5 pagesHyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: ReferenceFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: ReferenceDocument5 pagesHyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: ReferenceFariz NurNo ratings yet

- Garlic Benefits - Can Garlic Lower Your Cholesterol?Document4 pagesGarlic Benefits - Can Garlic Lower Your Cholesterol?Jipson VargheseNo ratings yet

- 1989 GMC Light Duty Truck Fuel and Emissions Including Driveability PDFDocument274 pages1989 GMC Light Duty Truck Fuel and Emissions Including Driveability PDFRobert Klitzing100% (1)

- AI Model Sentiment AnalysisDocument6 pagesAI Model Sentiment AnalysisNeeraja RanjithNo ratings yet

- B. Pharmacy 2nd Year Subjects Syllabus PDF B Pharm Second Year 3 4 Semester PDF DOWNLOADDocument25 pagesB. Pharmacy 2nd Year Subjects Syllabus PDF B Pharm Second Year 3 4 Semester PDF DOWNLOADarshad alamNo ratings yet

- Datasheet PDFDocument6 pagesDatasheet PDFAhmed ElShoraNo ratings yet

- Parts of ShipDocument6 pagesParts of ShipJaime RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Coleman Product PageDocument10 pagesColeman Product Pagecarlozz_96No ratings yet

- Young Women's Sexuality in Perrault and CarterDocument4 pagesYoung Women's Sexuality in Perrault and CarterOuki MilestoneNo ratings yet

- EP - EngineDocument4 pagesEP - EngineAkhmad HasimNo ratings yet

- CAT Ground Engaging ToolsDocument35 pagesCAT Ground Engaging ToolsJimmy Nuñez VarasNo ratings yet

- Gas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosDocument319 pagesGas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosLuis Eduardo LuceroNo ratings yet

- Monster of The Week Tome of Mysteries PlaybooksDocument10 pagesMonster of The Week Tome of Mysteries PlaybooksHyperLanceite XNo ratings yet

- Features Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N MDocument4 pagesFeatures Integration of Differential Binomial: DX BX A X P N Mابو سامرNo ratings yet

- Guidance Notes Blow Out PreventerDocument6 pagesGuidance Notes Blow Out PreventerasadqhseNo ratings yet

- Gautam Samhita CHP 1 CHP 2 CHP 3 ColorDocument22 pagesGautam Samhita CHP 1 CHP 2 CHP 3 ColorSaptarishisAstrology100% (1)

- Current Relays Under Current CSG140Document2 pagesCurrent Relays Under Current CSG140Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Is.4162.1.1985 Graduated PipettesDocument23 pagesIs.4162.1.1985 Graduated PipettesBala MuruNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsDocument7 pagesChap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsMc LiviuNo ratings yet

- Cost Analysis and Financial Projections for Gerbera Cultivation ProjectDocument26 pagesCost Analysis and Financial Projections for Gerbera Cultivation ProjectshroffhardikNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Challenges For Firms To Operate in The Hard-Boiled Confectionery Market in India?Document4 pagesDiscuss The Challenges For Firms To Operate in The Hard-Boiled Confectionery Market in India?harryNo ratings yet

- Telco XPOL MIMO Industrial Class Solid Dish AntennaDocument4 pagesTelco XPOL MIMO Industrial Class Solid Dish AntennaOmar PerezNo ratings yet

- What Is DSP BuilderDocument3 pagesWhat Is DSP BuilderĐỗ ToànNo ratings yet

- The Art of Now: Six Steps To Living in The MomentDocument5 pagesThe Art of Now: Six Steps To Living in The MomentGiovanni AlloccaNo ratings yet

- Magnetic Pick UpsDocument4 pagesMagnetic Pick UpslunikmirNo ratings yet

- PC3 The Sea PeopleDocument100 pagesPC3 The Sea PeoplePJ100% (4)

- Pioneer XC-L11Document52 pagesPioneer XC-L11adriangtamas1983No ratings yet

- CP 343-1Document23 pagesCP 343-1Yahya AdamNo ratings yet