Professional Documents

Culture Documents

743 2704 1 PB

Uploaded by

Tulio StephaniniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

743 2704 1 PB

Uploaded by

Tulio StephaniniCopyright:

Available Formats

Vol. 10, No.

3, Spring 2013, 505-509

www.ncsu.edu/project/acontracorriente

Review/Resena

Rothwell, Matthew D. Transpacific Revolutionaries: The Chinese

Revolution in Latin America. Routledge studies in modern

history, 10. New York: Routledge, 2012.

The Chinese in America

Marc Becker

Truman State University

We have long needed a book such as that which Matthew

Rothwell provides in Transpacific Revolutionaries. His work on the

important

influence

of

Chinese

maoists

on

Latin

American

revolutionary thought and action fills a significant gap in our

understandings of Latin American marxism. His attention to southsouth material flows and intellectual influences, together with a focus

on Latin American agency, provides us with important methodological

breakthroughs that take us well beyond Eurocentric Cold War-bound

determinants for understanding the emergence of Latin American

revolutions.

Rothwells study of Latin American maoism is focused through

the limited but well selected studies of Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia. While

Becker

506

they are only part of a much larger phenomenon, these three countries

provide excellent examples of the range of influences that maoism

played in Latin America. Several commonalities link these case studies.

In the 1960s, many of these activists traveled to China (apparently with

funds from the Chinese government). Rothwell notes that this travel

played a key role in the domestication of maoism in Latin America,

while at the same time providing these militants with legitimacy and

authority that they could exercise on their return. Furthermore, these

maoist influences should not be seen as Chinas attempt to extend its

imperial reach into Latin America, but rather something that was

sought out and cultivated by Latin Americans themselves.

Rothwell begins with Mexico and famed labor leader Vicente

Lombardo Toledano, who fortuitously attended a 1949 meeting of the

World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) in Beijing shortly after the

consolidation of the communist victory. Lombardo was drawn to the

Chinese model because of its parallels with the Mexican Revolution. His

initial contact led to a series of close contacts between Mexican leftists

and Chinese revolutionaries in the 1960s. Perhaps most significant was

Florencio Medranos attempts to emulate Maos strategies with a

protracted peoples war in the border region between Oaxaca and

Veracruz in the 1970s. Maoisms continuing influence in Mexico is

apparent in how subsequently political parties coopted their cadre and

political influences.

Maoisms strongest influence emerged in Perus Shining Path

guerrilla insurgency. Particularly in Peru, maoism not only represented

a schism from the pro-Soviet party, but also provided an arena of

subsequent divisions between different maoist groups, of which the

Shining Path was initially one of the smallest and most insignificant

tendencies. Rothwell observes that many scholars fail to understand the

emergence of the Shining Path as Latin Americas most powerful

guerrilla insurgency because of a lack of expertise in the intricacies of

maoist thought in China. He argues that the movement can only be

properly understood within that context.

Debates have long raged on the left as to the nature of the

influences of Perus famed marxist founder Jos Carlos Maritegui on

the thought of Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmn. Rothwell argues

that while these influences represented more of an effort to

The Chinese in America

507

conceptualize Mariteguis ideology in light of Maos contributions than

a reworking of Mao in light of Maritegui (69), this process would not

have happened had not Shining Path leaders understood a need to

adapt maoism to Peruvian conditions rather than directly and

mechanically importing these ideologies. In addition, Rothwell points to

a creative process of everyday adaptation and domestication that took

place when mid-level cadres read and interpreted Mao through their

own processes of socialization in Peru.

Rothwells third case study of Bolivia provides a counterpart to

Peru, and a historical situation that seemingly would be more likely to

provide a rich bed for the emergence of maoist thought. In particular,

the Chinese example should have logically provided an appealing model

after the 1952 MNR revolution. Nevertheless, as Rothwell points out,

China becomes more of a point of reference than a model. Rothwell

advances a geopolitical explanation of Juan Velascos nationalist

government providing more political space for activists in Peru than did

Bolivias more repressive military regimes as a partial explanation for

different growth patterns, but one senses that a much deeper and more

complicated story exists here. For example, a 1970 attempted uprising

in Bolivias eastern region repeated Che Guevaras failure three years

earlier, but had several factors played out differently it might have

grown into a massive uprising, while the Shining Path subsequently

withered away into a minor historical footnote. This contrast highlights

that history is not mechanically written, and many different possible

outcomes exist. A larger point might underscore the roles humans play

in determining a specific historical outcome.

In many ways, Rothwell only provides an introduction to the

topic of maoist ideological influences on the Latin American left and his

study suggests that more work needs to be done. For example, Bolivia is

much more known for being one of the few places where trotskyism

gained a strong foothold.1 What were the interactions like between the

maoists and trotskyists? Che Guevara was a notoriously heterodox

ideologue, drawing on multiple influences but refusing to be identified

1 The best work on trotskyism in Bolivia is S. Sndor John, Bolivia's

Radical Tradition: Permanent Revolution in the Andes (Tucson: University of

Arizona Press, 2009). Also see Robert L. Smale, I Sweat the Flavor of Tin:

Labor activism in early twentieth-century Bolivia, Pitt Latin American series

(Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010).

Becker

508

with any one trend. In fact, guevarism came to be seen as yet one more

political line in the ideologically fragmented 1960s. Despite a common

peasant

strategy,

clear

divisions

emerged

between

Guevaras

insurrectionist foco theory and Maos prolonged peoples war, perhaps

most visibly apparent in divisions within the Sandinista movement in

Nicaragua in the 1970s. Rothwells work suggests the need for deeper

study of maoist influences on Guevara, and the influence Guevara had

on the formation of maoist ideologies in Latin America.

Rothwells study also references tantalizing details that might

shed light on the diversity of the Latin American left. One minor

example is a request by Peruvian and Ecuadorian delegates at a 1959

seminar in China for a study of national minorities. A study of the

National Problem, of course, was a concern of Stalins, and was

introduced into Latin America in the 1920s as a defense of the rights of

Indigenous nationalities. Pro-Soviet communist parties subsequently

became renowned for their defense of Indigenous and African

descendant peoples. China ignored the request for such a study at the

1959 seminar, and subsequently the Shining Path came under harsh

criticism for ignoring the ethnic dimensions of their struggle. The

Peruvian maoists were not alone in their shortcomings in this regard, as

Rothwell points out that this was also an issue with the Bolivian maoist

party. Perhaps this is part of a larger question connected to how

different analyses of the national question divided the left, and we have

failed to understand these dynamics due to our shortcomings of debates

within maoism.

Considering the important but often unacknowledged influence

of maoism in Latin America, Rothwell asks why exactly have maoists

been ignored. He postulates four thought-provoking factors that

contribute to a more sophisticated understanding of the Latin American

left. First is the common Cold War tendency among historians to focus

on Europe to the exclusion of Asian and African influences, together

with a tendency to deny political agency to Latin Americans. Just as

significant, however, is a lack of knowledge of Chinese history and

politics among Latin Americanists. Rothwell argues that if we had a

stronger understanding of the intricacies of the evolution of maoism in

China, its influences in Latin America would become clearer. Third is

the revulsion among scholars against the level of violence that the

The Chinese in America

509

Shining Path insurgency engendered in Peru, which has hindered

studies that might contribute to a deeper appreciation for maoist

influences in Latin America. And, finally, Rothwell points to the

weakness of Chinas current political influence in Latin America as

hindering a historical analysis of maoism in the region.

Ironically, China now has a more visible and marked material

presence in the region than ever before, but rather than contributing to

a subversive ideology it has become part of the logic of capitalist-driven

neo-extractivist economies. But even Chinas current role represents a

continuation of part of its historical attraction for Latin America.

Beginning with the 1949 revolution, some leftists saw maoism as a

model for how to organize a successful guerrilla struggle that should be

emulated in Latin America. For others, however, Chinas great leap

forward provided a model for economic modernization that would allow

for the development of Latin Americas impoverished economies. It is

that development model that has led leftist governments ranging from

Cuba to Ecuador to pursue a significant warming of relations with

China. Unfortunately, these contemporary leaders seem to ignore the

fact that Chinas market-driven (read: capitalist) policies lead to rapidly

rising rates of inequality that in part originally led to a push for a

socialist revolution. It is in this context that we still have a lot to learn

about maoist influences in Latin America. Rothwells Transpacific

Revolutionaries provides an excellent starting point.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Snap OnDocument652 pagesSnap OnAbdullah Alomayri75% (4)

- Social StudiesDocument15 pagesSocial StudiesRobert AraujoNo ratings yet

- PesquisaDocument2 pagesPesquisaTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Bullying en La SecundariaDocument272 pagesBullying en La SecundariaGiancarlo Castelo100% (1)

- Naval - British MarinesDocument73 pagesNaval - British MarinesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (6)

- Research Proposal Sex Addiction FinalDocument14 pagesResearch Proposal Sex Addiction Finalapi-296203840100% (1)

- Forensic Examination Report - Kevin SplittgerberDocument16 pagesForensic Examination Report - Kevin Splittgerberapi-546415174No ratings yet

- Master-at-Arms NAVEDTRA 14137BDocument322 pagesMaster-at-Arms NAVEDTRA 14137B120v60hz100% (2)

- Gudani v. Senga, Case DigestDocument2 pagesGudani v. Senga, Case DigestChristian100% (1)

- Dynamic Kali Knife DefenseDocument20 pagesDynamic Kali Knife DefenseTulio Stephanini100% (2)

- Dynamic Kali Knife DefenseDocument20 pagesDynamic Kali Knife DefenseTulio Stephanini100% (2)

- Deed of Chattel MortgageDocument2 pagesDeed of Chattel MortgageInnoKal100% (1)

- Defender Of: Protector of Those at SeaDocument2 pagesDefender Of: Protector of Those at SeaElenie100% (3)

- Judicial Clemency GuidelinesDocument13 pagesJudicial Clemency GuidelinesMunchie MichieNo ratings yet

- ReadmeDocument5 pagesReadmeSergio AlleNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument16 pages1 PBTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Tribologia Livros para PesquisaDocument1 pageTribologia Livros para PesquisaTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Repot Permissão de Porte de Armas EuaDocument27 pagesRepot Permissão de Porte de Armas EuaTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Abortion Regret StudyDocument16 pagesAbortion Regret Studyfawkes316No ratings yet

- That Was FAST - Yesterday It Was Gay Marriage Now Look Who Wants - Equal Rights - Allen B. West - AllenBWestDocument6 pagesThat Was FAST - Yesterday It Was Gay Marriage Now Look Who Wants - Equal Rights - Allen B. West - AllenBWestTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Inter-American Dialogue - Fernando Henrique CardosoDocument3 pagesInter-American Dialogue - Fernando Henrique CardosoTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Firearms - ! - Full Auto Conversion - AK-47 RifleDocument17 pagesFirearms - ! - Full Auto Conversion - AK-47 Riflemsjohnso1100% (2)

- Inter-American Dialogue - Marina SilvaDocument3 pagesInter-American Dialogue - Marina SilvaTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff Has Left The U.S Territory Without Paying For v.I.P Presidential Limousine Services Provided in San FranciscoDocument5 pagesBrazil's President Dilma Rousseff Has Left The U.S Territory Without Paying For v.I.P Presidential Limousine Services Provided in San FranciscoTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Content of A New-Generation WarDocument12 pagesThe Nature and Content of A New-Generation WarHenry Arnold100% (1)

- China Electronic Intelligence Elint Satellite Developments Easton StokesDocument28 pagesChina Electronic Intelligence Elint Satellite Developments Easton StokesTulio StephaniniNo ratings yet

- Properties and VOD of Common ExplosivesDocument8 pagesProperties and VOD of Common ExplosivesbiaravankNo ratings yet

- LubricacionDocument10 pagesLubricacioncarardo86No ratings yet

- LubricacionDocument10 pagesLubricacioncarardo86No ratings yet

- Cyber Law ProjectDocument19 pagesCyber Law ProjectAyushi VermaNo ratings yet

- Stradec v. SidcDocument2 pagesStradec v. SidcFrancis Jan Ax ValerioNo ratings yet

- Remedial Criminal Procedure DraftDocument20 pagesRemedial Criminal Procedure DraftAxel FontanillaNo ratings yet

- 04 Task Performance 1Document4 pages04 Task Performance 1Amy Grace MallillinNo ratings yet

- Process Reflection: The 2nd Southeast Asia Legal Advocacy TrainingDocument12 pagesProcess Reflection: The 2nd Southeast Asia Legal Advocacy TrainingAzira AzizNo ratings yet

- Women's Estate Under Hindu Succession ActDocument11 pagesWomen's Estate Under Hindu Succession ActDaniyal sirajNo ratings yet

- The First American Among The Riffi': Paul Scott Mowrer's October 1924 Interview With Abd-el-KrimDocument24 pagesThe First American Among The Riffi': Paul Scott Mowrer's October 1924 Interview With Abd-el-Krimrabia boujibarNo ratings yet

- Business Law Moot Props 2023, MayDocument15 pagesBusiness Law Moot Props 2023, MayKomal ParnamiNo ratings yet

- (Digest) Marimperia V CADocument2 pages(Digest) Marimperia V CACarlos PobladorNo ratings yet

- TEST 1 - LISTENING - IELTS Cambridge 9 (1-192)Document66 pagesTEST 1 - LISTENING - IELTS Cambridge 9 (1-192)HiếuNo ratings yet

- Cindy Hyde-Smith Opposes Reproductive Care Privacy RuleDocument11 pagesCindy Hyde-Smith Opposes Reproductive Care Privacy RuleJonathan AllenNo ratings yet

- The Boxer Rebellion PDFDocument120 pagesThe Boxer Rebellion PDFGreg Jackson100% (1)

- Attested To by The Board of Directors:: (Position) (Position) (TIN No.) (Tin No.)Document2 pagesAttested To by The Board of Directors:: (Position) (Position) (TIN No.) (Tin No.)Noreen AquinoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledapi-183576294No ratings yet

- A A ADocument5 pagesA A AZeeshan Byfuglien GrudzielanekNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 3Document3 pagesTutorial 3Wen ChengNo ratings yet

- Ge2 - The Campaign For IndependenceDocument26 pagesGe2 - The Campaign For IndependenceWindie Marie M. DicenNo ratings yet

- George Washington - Farewell Address of 1796Document11 pagesGeorge Washington - Farewell Address of 1796John SutherlandNo ratings yet

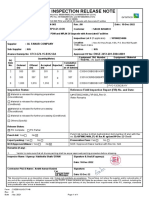

- IL#107000234686 - SIRN-003 - Rev 00Document1 pageIL#107000234686 - SIRN-003 - Rev 00Avinash PatilNo ratings yet

- Bureau of Jail Management and PenologyDocument5 pagesBureau of Jail Management and PenologyChalymie QuinonezNo ratings yet