Professional Documents

Culture Documents

tmp18AB TMP

Uploaded by

FrontiersOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

tmp18AB TMP

Uploaded by

FrontiersCopyright:

Available Formats

International Symposium on Performance Science

ISBN 978-94-90306-01-4

The Author 2009, Published by the AEC

All rights reserved

Expressive timing: Martha Argerich plays

Chopins Prelude op. 28/4 in E minor

Olivier Senn, Lorenz Kilchenmann, and Marc-Antoine Camp

Institute for Music Performance Studies, Lucerne School of Music, Switzerland

This paper scrutinizes the temporal organization of Martha Argerichs

interpretation of Chopins Prelude op. 28/4 in E minor, recorded in 1975

for Deutsche Grammophon (DG 415 836-2). It proposes a method for

extracting the timing of the attacks from the audio signal, it visualizes the

data of bars 1-4, and maps Argerichs timing to Chopins composition in a

process of inverse interpretation.

Keywords: microtiming; interpretation; piano; Martha Argerich; Frdric Chopin

When Western art music is performed, microrhythmic organization often

differs considerably from the notated rhythm of the score; these deviations

can be referred to as expressive timing (Clarke 1999) and have been studied

intensely in empirical rhythm research (see Pfleiderer 2006 for an overview).

There has been a considerable amount of research concerning performance

invariants in time organization; most of it analyzed performances of classical/romantic piano music on recordings. Several studies present evidence

that performers tend to slow down at the end of a melodic phrase (e.g. Repp

1998, Clarke 1999) and that melody voices anticipate accompanying voices by

a few milliseconds (melody lead, e.g. Palmer 1989, Goebl 2001). Most conclusions endorse a general assumption in music performance research that

expressive timing relates closely to structural features of a composition (e.g.

Clarke 1988, Palmer 1996).

Against this background of invariant performance behavior, we would like

to analyze one particular recording as an individual response to a composition: between 22-25 October 1975, Martha Argerich recorded Frdric Chopins Preludes op. 28 in Munich for Deutsche Grammophon (catalogue

number DG 415 836-2). Our analysis in this paper concentrates on the temporal organization of the E minor Prelude op. 28/4, bars 1-4 (although meas-

108

WWW.PERFORMANCESCIENCE.ORG

urements for the whole piece have been made). It divides the fabric of the

Prelude into two rhythmic layers: the solo voice in the right hand and the

sequence of accompanying chords in the left hand each have their own

rhythmic structure (see Figure 2) and are analyzed separately. Finally, the

timing phenomena are related to the score in a speculative process of inverse

interpretation: inspired by Timmers et al. (2000), we assume that there is a

great number of possible ways to analyze the structure of a composition. We

do not analyze the compositional structure first, and map it to the performance data later, but the other way around. We inspect the timing data and try

to separate expected phenomena from Argerichs individual approach. Then,

the score of the piece is analyzed in order to find the properties that are highlighted by Argerichs interpretation. This analysis is done strictly from a listeners point of view: we are not trying to reconstruct Argerichs thoughts or

intentions. But we do try to articulate which sense or meaning weas listenersmight discover in Argerichs interpretation of Chopins piece.

MAIN CONTRIBUTION

Method

Our method to secure tone onset times seeks to meet two requirements: it

must allow us to differentiate tone onsets in two separate rhythmic layers

(solo voice and accompaniment), and the accuracy of the measurements must

be within 10 ms. Our approach implies two steps. First, we marked the onsets

roughly in a sonogram (window size=4410 samples, hop size=441 samples);

this places the timing in a range of 20 ms near the attack time. Since the

notes of the accompaniment chords are not necessarily struck at the same

time, only the onset of the loudest note of each chord was measured. In a

second step we adjusted the measurements with the help of filters and two

loudness measurements: a narrow bandpass filter (bandwith=100 Hz) was

employed to isolate the fundamental tone (or, if necessary, one of the first

partials) of a note; the delay caused by the filtering was compensated. Then,

the behavior of two loudness measurements was interpreted in order to detect the precise timing of the onset. It was set to the moment when a fast peak

level (window size=1 ms) overshoots an RMS level (27 ms) which reacts early

but slowly to an energy surge. First tests with monophonic piano examples

suggest that this method places the timing markers within a range of 2-12 ms

after the physical onset; more systematic tests need yet to be conducted in

order to evaluate this (rather conservative) estimate. All measurements and

the visualizations of timing data in Figure 2 were made with the Lucerne Audio Recording Analyzer (software freely available at www.hslu.ch/lara).

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON PERFORMANCE SCIENCE

109

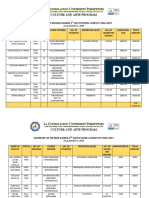

Figure 1. Average distribution of bar duration on the 8 eighth notes in the accompaniment in % (calculated with timing data from bars 1-11 and 13-22).

Analysis

In bars 1-11 and 13-22, the accompaniment of Chopins Prelude op. 28/4 consists of a rhythmically uniform sequence of chords, pulsating in eighth notes.

Argerich plays these eighth notes with flexible rhythm; nevertheless, a general bar profile is discernible.

Figure 1 shows the mean distribution of bar durations among the 8 eighth

notes of a bar throughout the whole piece (in % of bar duration). Two ritardando zones can be identified: one strong ritardando spans over the bar line,

from eighth note 7 (13.1% of bar time) and the longest 8 (15.2%) to 1 (14.2%).

We would like to call this formation bar line ritardando. Another, much

more subtle lengthening concerns eighth note 5 (12.7%). We call this the

mid-bar ritardando. Besides the performance invariants reported in the

research literature (slowing down on phrase endings, melody lead), this average bar profile can serve us as a background for identifying Argerichs individual reactions to particular configurations within the composition.

Figure 2 presents Argerichs rhythmic disposition of bars 1-4 alongside

the respective excerpt of the score. The rhythm diagram just above the score

(L for left hand) represents the timing of the accompaniment: every vertical

line on the horizontal timeline marks the timing of a detected onset. The

width (and consequently the height) of the squares represent the inter-onsetintervals (IOI) on different metrical levels of the score. The smallest squares

denote IOIs between neighboring eighth notes, the biggest squares denote

IOIs between successive downbeatsi.e. they represent bar durations. All

IOIs are given as a tiny numerical value (in ms) in the upper part of each

square. The top rhythm diagram in Figure 2 (R for right hand) represents

the timing of the solo melody: the smaller squares stand for the anacrusis, the

dotted half notes, and the quarter notes, respectively. The biggest squares

visualize bar durations analogous to the lower diagram. Both diagrams (R+L)

are adjusted horizontally to the same timeline. The numbers between the

110

WWW.PERFORMANCESCIENCE.ORG

Figure 2. Rhythm diagram and score (according to G. Henle edition, 1968), bars 1-4.

diagrams represent differences between onsets in the right and the left hand,

whichaccording to the scoreoccupy the same metric position. Most of the

time, Argerich plays the solo voices onsets earlier than the accompaniments:

in bars 1-4, the melody leads in seven of nine instances (78%), the average

melody lead is 28 ms.

Argerich takes up the slow tempo of the anacrusis in the accompaniment.

In bar 1, she starts with a quite long first eighth note (807 ms) which takes

17.2% of bar duration; then she speeds up. No mid-bar ritardando is discernible in bar 1, but the bar line ritardando (eighth notes 7 and 8) is distinct. In

bar 2, Argerich starts fast but slows down considerably in the second half of

the bar. This tendency is even stronger in bar 3: the first half of bar 3 is fast

(28.7 bpm) and takes only 43.6% of bar duration (2092 ms), whereas the

second half is considerably slower (22.2 bpm) and lasts for 56.4% of bar duration (2704 ms).

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON PERFORMANCE SCIENCE

111

Which properties in the score might trigger the rhythmic phenomena of

bars 1-3? Our attempt at inverse interpretation focuses on the repetitive pattern of the solo voice: the piece receives a first impulse from the octave leap of

the anacrusis. Then the solo melody seems to be stuck in repetitionthe motif C5-B4 is repeated three times in an identical way. With her fine sense of

dramaturgy, Argerich seems to make a new effort to gain some speed with

every new bar (hence the faster first halves), but this effort is lost as the bar

progresses, the tension relaxes and the music seems to stagnate.

The situation changes completely in bar 4: the bar line ritardando is absent, but the mid-bar ritardando appears for the first time and very distinctively on bar 4, eighth note 5 (704 ms, 15.8%). Why is that? At the end of bar

4, the solo melody progresses from the repeated melodic pattern C5-B4it

descends one tone to Bb4-A4. Following the research literature, we would

expect the tempo to slow down at the end of bar 4, which is the end of the first

4-bar period. But the contrary is the case: after the mid-bar ritardando of bar

4, Argerich speeds up again. This development makes sense, if we take into

account that the quarter notes of the melody are most likely heard as anacruses to the dotted half notes on the downbeats. The Bb4 quarter note in the

solo melody at the end of bar 4, thus, does not belong to the first 4-bar period

but to the next formal entity. With the pronounced mid-bar ritardando of bar

4, Argerich slows down at the end of the first period just before this anacrustic Bb4, and then gathers speed for the second period: the melodic anacrusis

to bar 5 gives a new impulse to the piece, and the rhythm of the accompaniment supports this impulse. Compared with bars 3 (25.1 bpm) and 4 (27.0

bpm), bar 5 speeds up considerably (31.8 bpm).

IMPLICATIONS

Using time measurements, we described the microrhythmic fabric of the first

4-bar passage in Martha Argerichs 1975 recording of Chopins Prelude op.

28/4. The specificity of her rhythmic interpretation was established against

the background of rhythm performance invariants (as reported in the research literature) and an averaged profile of the eighth note lengths in her

recording. Then, in a process of inverse interpretation, we have tried to figure

out constellations in the score that might have triggered Argerichs specific

approach. This procedure casts an analytical light on the composition through

the lens of a concrete performance. It is no news that we can learn a great

deal about structural features of a composition by listening to an eminent

performer. Inverse interpretation attempts to transfer some of this intuitive

knowledge into the explicit domain of music performance studies.

112

WWW.PERFORMANCESCIENCE.ORG

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Rink for giving the first idea to do this paper, Claudia

Emmenegger for typesetting the music example, and Richard Beaudoin for his careful

proofreading and inspiring collaboration. Many thanks go to the faculty and the students of the Department of Music at Harvard University for their constructive comments on an early draft of this paper.

Address for correspondence

Olivier Senn, Institute for Music Performance Studies, Lucerne School of Music, Zentralstrasse 18, 6003 Lucerne, Switzerland; Email: olivier.senn@hslu.ch

References

Clarke E. F. (1988). Generative principles in music performance. In J. A. Sloboda (ed.),

Generative Processes in Music (pp. 1-26). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Clarke E. F. (1999). Rhythm and timing in music. In D. Deutsch (ed.), The Psychology

of Music (pp. 473-500). San Diego, California, USA: Academic Press.

Goebl W. (2001). Melody lead in piano performance: Expressive device or artifact?

Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110, pp. 563-572.

Goebl W. and Palmer C. (2009). Synchronization of timing and motion among performing musicians. Music Perception, 26, pp. 427-438.

Palmer C. (1989). Mapping musical thought to musical performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 15, pp. 331-346.

Palmer C. (1996). On the assignment of structure in music performance. Music Perception, 14, pp. 23-56.

Pfleiderer M. (2006). Rhythmus: Psychologische, Theoretische und Stilanalytische

Aspekte Populrer Musik. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag.

Repp B. H. (1998). Obligatory expectations of expressive timing induced by perception

of musical structure. Psychological Research, 61, pp. 33-43.

Timmers R., Ashley R. D., Desain P., and Heijink H (2000). The influence of musical

context on tempo rubato. Journal of New Music Research, 29, pp. 131-158.

You might also like

- tmp3CAB TMPDocument16 pagestmp3CAB TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpCE8C TMPDocument19 pagestmpCE8C TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpFFE0 TMPDocument6 pagestmpFFE0 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpE7E9 TMPDocument14 pagestmpE7E9 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp6F0E TMPDocument12 pagestmp6F0E TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpE3C0 TMPDocument17 pagestmpE3C0 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpF178 TMPDocument15 pagestmpF178 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp80F6 TMPDocument24 pagestmp80F6 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpEFCC TMPDocument6 pagestmpEFCC TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Tmp1a96 TMPDocument80 pagesTmp1a96 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpF3B5 TMPDocument15 pagestmpF3B5 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Tmpa077 TMPDocument15 pagesTmpa077 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp72FE TMPDocument8 pagestmp72FE TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpF407 TMPDocument17 pagestmpF407 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpC0A TMPDocument9 pagestmpC0A TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp60EF TMPDocument20 pagestmp60EF TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp8B94 TMPDocument9 pagestmp8B94 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp6382 TMPDocument8 pagestmp6382 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp998 TMPDocument9 pagestmp998 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp4B57 TMPDocument9 pagestmp4B57 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp9D75 TMPDocument9 pagestmp9D75 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp37B8 TMPDocument9 pagestmp37B8 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpC30A TMPDocument10 pagestmpC30A TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpD1FE TMPDocument6 pagestmpD1FE TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpB1BE TMPDocument9 pagestmpB1BE TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp3656 TMPDocument14 pagestmp3656 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmpA0D TMPDocument9 pagestmpA0D TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Tmp75a7 TMPDocument8 pagesTmp75a7 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp27C1 TMPDocument5 pagestmp27C1 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- tmp2F3F TMPDocument10 pagestmp2F3F TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Guitar World - 08.2023Document112 pagesGuitar World - 08.2023Aristides LambogliaNo ratings yet

- Nirvana BioDocument3 pagesNirvana BioYaasheikh PdmNo ratings yet

- Wenceslao Piano NiñosDocument1 pageWenceslao Piano NiñosElita FlamencoNo ratings yet

- Classic Pop Special Edition Madonna 2017Document133 pagesClassic Pop Special Edition Madonna 2017Toshiro Nakagaua33% (3)

- Lyrical AnalysisDocument5 pagesLyrical Analysisapi-252880253No ratings yet

- Love StoriesDocument35 pagesLove StoriesAskar MettaNo ratings yet

- 8 Examples of Great Co-Branding Partnerships: 1) Gopro & Red Bull: "Stratos"Document25 pages8 Examples of Great Co-Branding Partnerships: 1) Gopro & Red Bull: "Stratos"Jaquelyn ClataNo ratings yet

- Event Management Unit-1 PDFDocument28 pagesEvent Management Unit-1 PDFHardik SNo ratings yet

- Wien - Info Programm 2016 11 de en FR ItDocument48 pagesWien - Info Programm 2016 11 de en FR ItgaborkNo ratings yet

- At The Table of The LordDocument3 pagesAt The Table of The LordPolly Pius EmmanuelsNo ratings yet

- Total 15 Records Found For Nickel Alloy TestingDocument7 pagesTotal 15 Records Found For Nickel Alloy TestingVasu RajaNo ratings yet

- 2005 08 22 Transcript Vito Magi Nick0822Document6 pages2005 08 22 Transcript Vito Magi Nick0822Montreal GazetteNo ratings yet

- IndianDocument32 pagesIndianIndian WeekenderNo ratings yet

- Famous Violinists & Fine ViolinsDocument270 pagesFamous Violinists & Fine ViolinsjuandaleNo ratings yet

- MJ RepresentationDocument22 pagesMJ RepresentationDee Watson100% (1)

- The Tristan Chord in ContextDocument16 pagesThe Tristan Chord in ContextJunior LemeNo ratings yet

- CanonDocument134 pagesCanonapi-302635768100% (1)

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 1-13-19Document28 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 1-13-19The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay About KpopDocument3 pagesArgumentative Essay About KpopEricka Garino100% (5)

- Summary of Income GainedDocument2 pagesSummary of Income GainedCatalinus SecundusNo ratings yet

- BLAWG - Shirts Come Off With Friends at MohawkDocument5 pagesBLAWG - Shirts Come Off With Friends at MohawkBere BelmaresNo ratings yet

- Book Cover Delaney WhiteDocument12 pagesBook Cover Delaney Whitewhitedelaney9892No ratings yet

- Valentine - Laufey (Arrangement For Solo Piano) Sheet Music For Piano (Solo)Document1 pageValentine - Laufey (Arrangement For Solo Piano) Sheet Music For Piano (Solo)thewtongprantNo ratings yet

- Jeni LegonDocument3 pagesJeni LegonVanessa MerendaNo ratings yet

- Ducha Serge Douce Fla 81418Document4 pagesDucha Serge Douce Fla 81418Rodrigo Balthar FurmanNo ratings yet

- MusicDocument356 pagesMusicJilly CookeNo ratings yet

- I Dont Want To Miss A ThingDocument3 pagesI Dont Want To Miss A ThingJohnny Albert RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Paste MagazineDocument116 pagesPaste Magazinegaga_gm29No ratings yet

- Guitar HarmonicsDocument2 pagesGuitar Harmonicspickquack100% (1)

- Introduction To The Scale Syllabus For Jazz - Jamey AebersoldDocument1 pageIntroduction To The Scale Syllabus For Jazz - Jamey AebersoldCwasi Musicman0% (1)