Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ava Checklist Booklet

Uploaded by

Catarina RafaelaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ava Checklist Booklet

Uploaded by

Catarina RafaelaCopyright:

Available Formats

Celebrating 50 years of championing safe anaesthesia

The Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST

IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL

First Edition, 2014

The checklist and implementation manual were written by the AVA

with design and distribution support from Jurox Pty Limited

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Executive Committee of the Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists (AVA)

for their help and guidance throughout this process. We would also like to thank all the vets,

nurses and technicians that gave input during the development of this project.

Project Chair

Matthew McMillan BVM&S, DipEVCAA, MRCVS

Key Contributors

Paul Coppens DMV, DipECVAA

Peter Kronen DVM, Dr med vet, DipECVAA

Paul Macfarlane BVSc, CertVA, DipECVAA, MRCVS

Sam McMillan VTS(Anesthesia), DipAVN(Med) RVN

Daniel Pang BVSc, PhD, DipECVAA, DipACVAA

Special Thanks

To Jurox for their design and distribution support with these safety initiatives.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

Introduction

Maintaining patient safety and comfort should be viewed as the

primary function of any anaesthetic.

The Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists (AVA) has a fifty year history of promoting safe

anaesthesia in veterinary medicine. In 2013 at the spring meeting of the AVA in London, a

proposal was made to further this by developing a number of initiatives to improve anaesthetic

safety at all levels of veterinary medicine. The primary task was to produce safety checklists and

guideline documentation for key points within the anaesthetic process.

Anaesthesia can often be viewed as a means to end; a state enabling surgery, invasive medical

and/or diagnostic procedures to be undertaken. Unfortunately this outlook often fails to

recognise the importance of maintaining the safety and comfort of our patients during these

procedures. Is it good enough to have an alive and awake patient at the end of anaesthesia?

The AVA strongly believes that we should challenge this view and strive to ensure that each

patients anaesthetic is managed safely (by recognising and minimising risks and appropriately

managing complications) and that significant measures are taken to ensure patient comfort.

Maintaining safety and comfort are simple enough sentiments but anaesthesia is a complex

process involving many critical steps that need to be performed in a correct and timely manner.

Within a busy veterinary clinic there can be a tendency to try and over-simplify this complexity

which can lead to steps being missed and vital components of a safe anaesthetic process

being overlooked. Each of us has the responsibility to do as much as possible to ensure that our

patients are kept both safe and comfortable and therefore the AVA has developed a number of

recommended procedures and checklists to act as cognitive aids during the peri-anaesthetic

period to assist in achieving this goal.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

Objectives

The objectives of these recommended procedures and checklists are threefold:

1.

2.

3.

To outline an appropriate manner and order in which to perform key procedures in the

anaesthetic process

To reinforce recognised safe practices by ensuring critical safety steps are performed before

moving between key points in the anaesthetic process

To improve teamwork and communication during the anaesthetic process

Adhering to these checklists will not guarantee safety. However they can be successful if the

culture of your practice is such that the patient is central to all of the systems and processes in

place.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

The Checklists: Background

..it is not the act of ticking off a checklist that reduces

complications, but performance of the actions it calls for

- Lucian Leape, 2014

A set of checklists has been devised that can be followed in almost all situations where

anaesthesia is being performed. The checklists are not designed to be a comprehensive list of

all steps in the anaesthetic process but rather a framework and set of tools to help ensure that

critical safety actions are performed. Each of the checks and steps have been included to reduce

the risk of significant avoidable harm that can occur during the anaesthetic process. Only those

considered inexpensive both in terms of time and finances have been included to ensure they

are achievable for all levels of veterinary practice. Running through the safety checklists we have

developed at the relevant times should ensure that none of the critical safety steps are missed.

All members of the veterinary team are responsible for the safety of the patient during an

anaesthetic, not just the veterinarian in overall charge of the case. In order to best ensure safety

each team member must be made aware of the critical safety points of the anaesthetic process

and any safety concerns regarding the patient and or procedure. Consequently the checklists

have been designed to facilitate the communication of essential safety information between

members of the veterinary team involved in the patients anaesthesia and the surgical/medical/

diagnostic procedure.

It is not the checklists themselves that are important; instead it is the ecient and eective

performance of the safety actions and communication outlined within them that are key to

improving safety. We therefore recognise that modifications may be required in individual

practices to allow them to be implemented eectively alongside other standard operating

procedures and protocols. It may be that the checklists will be more eectively implemented in

some institutions by applying them at dierent time points, or by adding or removing certain

items and we would encourage practitioners to tailor the checklist to their own institutions.

No checklist can be universal and implementation cannot guarantee safety. These checklists can

only be eective when used within a patient-centred approach to the anaesthetic process where

safety and comfort are the priority.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

The Checklists: How to use them

In a small team of two or three people the checklists can be implemented as a team with no

single person in charge of its completion, however in larger teams it is recommended that a

single person be made responsible for running the checklists. Ideally it should be a member of

the veterinary team that will be present throughout the procedure such as the veterinary nurse

or technician assigned to monitor the case.

For the purposes of the checklists the anaesthetic process has been divided into three phases.

The checklists have been designed to fit between these phases, slotting into natural breaks in

work-flow to avoid major delays. The time points are:

1.

2.

3.

immediately prior to induction of anaesthesia

immediately prior to the procedure beginning (e.g. before the first surgical incision is made)

immediately prior to recovering the patient

At each time point it should be confirmed that every check has been performed and that critical

safety and relevant patient information has been communicated between team members. Not

until all check points have been completed should the team move onto the next phase of the

anaesthetic process.

These checks can be easily integrated into normal practice work patterns without causing major

disruptions. The checks should be confirmed and communicated verbally to ensure each team

member is made aware of them.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

The Pre-Induction Checklist

To reduce the potential for any error occurring, it is important not to rush into the induction of

anaesthesia. So, prior to the administration of any anaesthetic drugs, it should be ensured that

the following critical safety steps have been performed.

Patient NAME, owner CONSENT & PROCEDURE confirmed

It is vital to ensure that the team is aware of who the patient is, what procedure is planned for

the patient and that appropriate informed owner consent for the anaesthesia and procedure

has been obtained. The consequences of mistakes such as anaesthetising the wrong patient,

performing an incorrect procedure or anaesthetising a patient without proper informed consent

can be disastrous and every attempt should be made so these events never occur.

IV CANNULA placed & patent

It is the recommendation of the AVA that an intravenous cannula is placed for anaesthesia

in all patients where this is practicable. This facilitates drugs being given to eect, allows

additional intravenous drugs and fluid therapy to be administered appropriately throughout

the anaesthetic period and ensures immediate venous access should an emergency occur. The

placement of this cannula should be confirmed by flushing with saline or heparinised saline prior

to the injection of any drugs.

AIRWAY EQUIPMENT available & functioning

A patent airway is a critical component of a safe anaesthetic. Although endotracheal intubation

may not be necessary in all cases, the ability to place an endotracheal tube or other suitable

airway device is vital. A selection of tube types and sizes should be available for all patients

where intubation is possible. The patency of tubes and airway devices should be checked by

visually inspecting the tube lumen.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

Other airway equipment, if available, should be checked ensuring that it functions appropriately.

In small animals useful airway equipment can include: local anaesthetic sprays, suitably sized

syringes to inflate endotracheal tube cus, laryngoscopes, suction devices, and potentially

malleable guide-wires or similar devices such as sti dog urinary catheters (which can be used

to insuate oxygen into the trachea and as guide-wires to place endotracheal tubes over in

dicult airways). In large animals useful airway equipment can include: mouth gags, a 50mL

syringe to inflate endotracheal tube cus, a flexible endoscope and non-irritant water based

lubricant.

Endotracheal tube CUFFS checked

Where endotracheal tubes have inflatable cus, these should be checked by inflating them and

ensuring that they do not deflate spontaneously. After checking, the cus should be deflated.

This ensures that the cu can be inflated in order to protect the airway and facilitate intermittent

positive pressure ventilation if it is required.

ANAESTHETIC MACHINE checked today

For the purpose of this document and the checklist the anaesthetic machine is considered to be

any device used to administer oxygen and/or anaesthetic gases to the patient. This could range

from a system as simple as an oxygen cylinder with a flowmeter to a full anaesthetic workstation

with integrated mechanical ventilator. It is essential to ensure that the machine is able to fulfill all

of its functions eectively.

A full anaesthetic machine check should be performed at the start of each day or session. A more

streamlined curtailed check should then be performed prior to each anaesthetic. See the AVAs

Recommended procedure for checking anaesthetic machines and equipment.

Adequate OXYGEN for proposed procedure

Although it may not be necessary to perform a full anaesthetic machine check before every

anaesthetic it is important to ensure that there is enough oxygen available to administer the

planned flow for the likely or potential duration of the proposed procedure.

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

BREATHING SYSTEM connected, leak free & APL VALVE OPEN

Ensure that there is a method to administer the oxygen to the patient and the ability to perform

manual intermittent positive pressure ventilation. This can be performed via an anaesthetic

breathing system with a reservoir bag or self-inflating bag (such as an AMBU-Bag) in small

animals and a large animal anaesthetic machine or demand valve in larger patients. The function

of these systems should be confirmed via a visual and manual check and through ensuring they

are leak free. Methods to leak test dierent anaesthetic breathing systems are described in the

AVAs Recommended procedure for checking anaesthetic machines and equipment.

A common error in anaesthesia at all levels is connecting a patient to a breathing system when

the adjustable pressure limiting (APL or pop-o ) valve has been left closed, this is especially

common during periods where many actions have to be performed in succession such as

induction. This can rapidly be fatal even with modern paediatric safety valves.

Person assigned to MONITOR patient

Things can go wrong even in what are considered to be routine or simple anaesthetics. It is

fundamental that a suitably trained person is assigned to monitor the patients physiological

parameters and depth of anaesthesia during anaesthesia. Nothing can replace properly trained

personnel in anaesthesia monitoring and the use of multi-parameter patient monitors should be

considered an aid and not a replacement for a person.

It is imperative to ensure that all personnel monitoring and involved in anaesthesia understand

the monitoring that is to be used, including any electronic monitoring available, and are able to

interpret the outputs produced accordingly.

RISKS identified & COMMUNICATED

Every anaesthetic, even the most straightforward, caries some risk and there are a number of

adverse events such as hypotension, hypoventilation, hypothermia and hypoxaemia that are

commonly encountered. However, there are a multitude of specific species, breed, disease

www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

and procedural risks that should also be identified and planned for prior to anaesthesia. A

properly performed pre-anaesthetic assessment and plan (as outlined in the recommended

procedure for pre-anaesthetic case assessment) will highlight potential complications and

outline interventions that should be undertaken. It is paramount that the patient specific risks

and proposed interventions are communicated to the entire veterinary team involved with the

anaesthetic to facilitate early identification and allow prompt and appropriate action in a crisis.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS available

Despite meticulous planning and implementation potentially fatal crises can occur during any

anaesthetic. Being able to perform basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation, gain an emergency

airway, administer intermittent positive pressure ventilation and administer fluid therapy and

drugs should be considered a basic requirement for all situations.

The list of equipment below should be available when performing anaesthesia in order to allow

these fundamental procedures to be performed.

10 www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

EMERGENCY

EQUIPMENT AND DRUGS LIST

(MINIMUM RECOMMENDED REQUIREMENTS)

Endotracheal tubes (cuffs checked)

Airway aids (e.g. laryngoscope, urinary catheter, lidocaine spray, suction, guide-wire/stylet)

Self-inflating bag/anaesthetic breathing system suitable for IPPV

(or demand valve for equine anaesthetics)

Epinephrine/adrenaline

Atropine

Antagonists (e.g. atipamezole, naloxone/butorphanol)

Intravenous cannulae

Isotonic crystalloid solution

Fluid administration set

Drug charts and CPR algorithm (http://www.acvecc-recover.org/)

At this point the PRE-INDUCTION CHECKLIST is completed.

www.ava.eu.com

11

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

The Pre-procedure Checklist

Before the procedure begins it is recommended that the entire team take a short time out in

order to perform the Pre-Procedure Checklist. This ensures that each part of the process is in

place and that each team member is ready and aware of the current situation.

Patient NAME & PROCEDURE confirmed

At this point the name and specific procedure the patient is undergoing should be confirmed

again. While it may seem repetitive, ensuring all team members are aware of the basics of the

case is essential for ensuring that they are prepared for what is to follow and that the correct

procedure is performed on the correct patient.

DEPTH of anaesthesia appropriate

Prior to commencing the procedure it is imperative to ensure that the patients depth of

anaesthesia is appropriate. Problems in anaesthesia often occur around times where there is a

sudden change in stimulation level as seen when going from the preparation phase (i.e. clipping

and aseptic preparation) to making the first incision.

SAFETY CONCERNS COMMUNICATED

At this point any patient concerns that members of the team have should be communicated.

Eective communication between members of the veterinary team is a critical component of

maintaining safety during the peri-anaesthetic period. This builds from the RISKS identified &

COMMUNICATED check and opens a forum for members of the team to highlight any current

concerns that they have about the patient, anaesthetic or procedure. This also presents an

opportunity for these problems to be addressed and to ensure that an intervention plan is in

place and prepared for.

At this point the PRE-PROCEDURE TIME OUT CHECKLIST is completed.

12 www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

The Recovery Checklist

We only have a limited understanding of how many complications occur during recovery;

however we do know that the proportion of anaesthetic related deaths occurring during this

period is high, especially within the first 2-3 hours following extubation (Brodbelt et al, 2008).

From this, it would appear that this is an area of patient management that often fails in veterinary

anaesthesia. It is therefore vital that all requirements for the patients post-anaesthetic care are

carefully considered and properly communicated at this stage. Sta handovers at this point in

the process are common as dierent nurses / technicians and or veterinary surgeons are often

responsible for the recovery or ward areas as compared to the anaesthetic and procedure. Each

team member should be made aware of the patients condition and specific needs.

SAFETY CONCERNS COMMUNICATED

Airway, Breathing, Circulation (fluid balance), Body Temperature, Pain

Clear and concise communication of the patients current condition is paramount. This should

include: the procedure performed, any complications which occurred under anaesthesia,

current parameters including body temperature and any other key concerns regarding

potential complications for the recovery period (e.g. a compromised airway, breakthrough pain,

haemorrhage etc).

ASSESSMENT & INTERVENTION PLAN confirmed

The monitoring and care plan for each patient will dier on an individual basis and an outline

of this plan should be communicated to those managing the recovery period. Clear guidelines

should be given as to what needs to be provided for the patient, which parameters should be

monitored and recorded and how often these should be done. Interventions should also be set

out so that all sta involved in the case are aware of what should be done if complications arise.

This can be as simple as knowing who to approach if a problem is encountered and at what

point they should be notified.

www.ava.eu.com

13

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

ANALGESIC PLAN confirmed

The provision of analgesia (drug, dose, time and route of administration) will have been recorded

on the anaesthetic monitoring chart but should also be clearly communicated to the person or

team responsible for recovery. Pain assessment plans (such as pain scoring methods) should be

outlined to help prevent too much or too little analgesia being provided to the patient. When

assessment is next due should be highlighted and a clear plan to manage breakthrough pain

should be discussed and recorded.

Person assigned to MONITOR patient

It is imperative that there is an individual assigned to monitor the patient during the recovery

period. Again this person should have suitable training and experience as the success of the

above planning and communication is completely dependent on the person assigned to

monitor and care for the patient.

At this point the RECOVERY CHECKLIST is completed.

14 www.ava.eu.com

ANAESTHETIC SAFETY CHECKLIST Implementation Manual

REFERENCES

Brodbelt, D.C., Blissitt, K.J., Hammond, R.A., Neath, P.J., Young, L.E., Pfeier, D.U., and Wood, J.N.L.

(2008). The risk of death: the Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Small Animal Fatalities.

Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 35, 365-373.

www.ava.eu.com

15

You might also like

- Patient Safety Guidelines for Anaesthesia MonitoringDocument21 pagesPatient Safety Guidelines for Anaesthesia MonitoringDzarrinNo ratings yet

- RUV40404 Certificate IV in Veterinary NursingDocument36 pagesRUV40404 Certificate IV in Veterinary NursingEdward FergusonNo ratings yet

- Prospectus of Paramedical College in Delhi - IPHIDocument16 pagesProspectus of Paramedical College in Delhi - IPHIParamedical CollegeinDelhiNo ratings yet

- Harvard Tools For Small Animal SurgeryDocument7 pagesHarvard Tools For Small Animal SurgeryJoel GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Dogs and CatsDocument8 pagesAtlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Dogs and CatsDama Ayu RaniNo ratings yet

- Fluidtherapy Guidelines PDFDocument11 pagesFluidtherapy Guidelines PDFJoão Pedro PereiraNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Dogs Undergoing Limb Amputation, Owner Satisfaction With Limb Amputation Procedures, and Owner Perceptions Regarding Postsurgical Adaptation: 64 Cases (2005-2012)Document7 pagesOutcomes of Dogs Undergoing Limb Amputation, Owner Satisfaction With Limb Amputation Procedures, and Owner Perceptions Regarding Postsurgical Adaptation: 64 Cases (2005-2012)William ChandlerNo ratings yet

- CVM New Freshman Student HandbookDocument19 pagesCVM New Freshman Student HandbookbaruruydNo ratings yet

- Birds and Exotics - MCannon PDFDocument42 pagesBirds and Exotics - MCannon PDFAl OyNo ratings yet

- Critical Transport GuidelinesDocument22 pagesCritical Transport GuidelinesFadil RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Media Analysis For SoundDocument32 pagesMedia Analysis For SoundJerralynDavisNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia and Analgesia Book 3 PDFDocument220 pagesAnesthesia and Analgesia Book 3 PDFhasted666No ratings yet

- Role of Anesthesia Nurse in Operation TheatreDocument37 pagesRole of Anesthesia Nurse in Operation TheatreZainul SaifiNo ratings yet

- Urinary Catheter Placement For Feline ObstructionDocument6 pagesUrinary Catheter Placement For Feline ObstructionWilliam ChandlerNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Nursing Skills MatrixDocument4 pagesVeterinary Nursing Skills MatrixGary75% (4)

- RSI For Nurses ICUDocument107 pagesRSI For Nurses ICUAshraf HusseinNo ratings yet

- Amputation of Tail in AnimalsDocument8 pagesAmputation of Tail in AnimalsSabreen khattakNo ratings yet

- Basic Life SupportDocument5 pagesBasic Life SupportbuenoevelynNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Pharmacology 2016Document6 pagesVeterinary Pharmacology 2016Stephan StephanNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia and Analgesia Book 1Document104 pagesAnesthesia and Analgesia Book 1JoanneYiNo ratings yet

- UCL Aneasthesia Year 4 Workbookv15Document83 pagesUCL Aneasthesia Year 4 Workbookv15Jay KayNo ratings yet

- Canine and Feline Skin Cytology-1Document10 pagesCanine and Feline Skin Cytology-1Hernany BezerraNo ratings yet

- Dog and Cat Parasite ControlDocument6 pagesDog and Cat Parasite ControlTyng-Yann YenNo ratings yet

- Uhns Guidelines 2010Document187 pagesUhns Guidelines 2010varrakesh100% (1)

- Book PDFDocument6 pagesBook PDFkv chandrasekerNo ratings yet

- Identify, Prepare, and Pass Instruments: Team Member Type of Role TimingDocument47 pagesIdentify, Prepare, and Pass Instruments: Team Member Type of Role TimingMuhammad Ihsan100% (1)

- ANAT.301 3 (1-2) : Veterinary Anatomy - I Theory One Class/ Week 20 Mrks Practical Two Classes/ WeekDocument34 pagesANAT.301 3 (1-2) : Veterinary Anatomy - I Theory One Class/ Week 20 Mrks Practical Two Classes/ WeekIftikhar hussainNo ratings yet

- Vet Coursework Assessment RecordDocument7 pagesVet Coursework Assessment Recordusutyuvcf100% (2)

- Orientation To AnesthesiaDocument28 pagesOrientation To AnesthesiaDebi SumarliNo ratings yet

- Current Diagnostic Techniques in Veterinary Surgery PDFDocument2 pagesCurrent Diagnostic Techniques in Veterinary Surgery PDFKirti JamwalNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Guidelines For Dogs and CatsDocument9 pagesAnesthesia Guidelines For Dogs and CatsNatalie KingNo ratings yet

- HEATS TRIAGE MANUAL TITLEDocument66 pagesHEATS TRIAGE MANUAL TITLEFitri SyawalNo ratings yet

- Sterile Processing Technician or Medical Supply Technician or MeDocument3 pagesSterile Processing Technician or Medical Supply Technician or Meapi-77583771No ratings yet

- CPR - Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDocument31 pagesCPR - Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationPanji HerlambangNo ratings yet

- Vet CareplanexampleDocument6 pagesVet CareplanexampleAnonymous eJZ5HcNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Cytology by Leslie C. Sharkey, M. Judith Radin, Davis SeeligDocument994 pagesVeterinary Cytology by Leslie C. Sharkey, M. Judith Radin, Davis SeeligBê LagoNo ratings yet

- Avian Anesthesia and SurgeryDocument10 pagesAvian Anesthesia and SurgeryRose Ann FiskettNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Critical CareDocument15 pagesVeterinary Critical Caresudanfx100% (1)

- Perioperative ServicesDocument2 pagesPerioperative Servicesmonir61No ratings yet

- ECG Basics 1Document24 pagesECG Basics 1Dr.U.P.Rathnakar.MD.DIH.PGDHMNo ratings yet

- Animal Trauma Triage ScoreDocument1 pageAnimal Trauma Triage ScoreVera SilvaNo ratings yet

- Uptake and Distribution of Volatile AnestheticsDocument22 pagesUptake and Distribution of Volatile AnestheticsSuresh Kumar100% (3)

- Obstetric HDU and ICU: Guidelines ForDocument52 pagesObstetric HDU and ICU: Guidelines ForsidharthNo ratings yet

- Canine Ehrlichiosis With Uveitis in A Pug Breed Dog: Case StudDocument2 pagesCanine Ehrlichiosis With Uveitis in A Pug Breed Dog: Case StudDR HAMESH RATRENo ratings yet

- Acls AnpDocument20 pagesAcls AnpNirupama KsNo ratings yet

- Fluidtherapy GuidelinesDocument11 pagesFluidtherapy Guidelineshamida fillahNo ratings yet

- Companion March2013Document36 pagesCompanion March2013lybrakissNo ratings yet

- Emergency Fluid Therapy in Companion Animals - PPitneyDocument9 pagesEmergency Fluid Therapy in Companion Animals - PPitneyUmesh GopalanNo ratings yet

- Dystocia in Mare: - By: Dr. Dhiren BhoiDocument50 pagesDystocia in Mare: - By: Dr. Dhiren BhoidrdhirenvetNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia TechnologyDocument56 pagesAnesthesia TechnologyDeepali SinghNo ratings yet

- Surgery of The Bovine Large IntestineDocument18 pagesSurgery of The Bovine Large IntestineJhon Bustamante CanoNo ratings yet

- Complications of Fluid TherapyDocument13 pagesComplications of Fluid TherapyElizabeth ArriagadaNo ratings yet

- ACKD in DogsDocument9 pagesACKD in DogsGreomary Cristina MalaverNo ratings yet

- Howto Companion April2012Document5 pagesHowto Companion April2012lybrakissNo ratings yet

- Neurologic Assessment RationaleDocument16 pagesNeurologic Assessment RationaleflorenzoNo ratings yet

- Regional Anesthesia in CattleDocument33 pagesRegional Anesthesia in Cattledemekegebeyehu5100% (2)

- Management of Arterial LineDocument16 pagesManagement of Arterial LineFarcasanu Liana GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- Bookshelf NBK546324Document30 pagesBookshelf NBK546324Catarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Artrodese UnocarpalDocument5 pagesArtrodese UnocarpalCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Cesária - Tiopental - QuetaminaDocument6 pagesCesária - Tiopental - QuetaminaCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Inhalants Used in Veterinary AnesthesiaDocument8 pagesInhalants Used in Veterinary AnesthesiaCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Artrodese UnocarpalDocument5 pagesArtrodese UnocarpalCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia of BearsDocument6 pagesAnesthesia of BearsRafael HaddadNo ratings yet

- Bookshelf NBK546324Document30 pagesBookshelf NBK546324Catarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- AVA AnaestheticSafetyChecklistDocument2 pagesAVA AnaestheticSafetyChecklistCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Mec Acao FarmacosDocument54 pagesMec Acao FarmacosLuís EduardoNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Evaluation of Tumescent Anaesthesia Technique in Bitches Submitted To Unilateral MastectomyDocument12 pagesPerioperative Evaluation of Tumescent Anaesthesia Technique in Bitches Submitted To Unilateral MastectomyCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Analgesia, Antinocicepção, DorDocument12 pagesAnalgesia, Antinocicepção, DorCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Impact of High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet on Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in Response to Mixed Meal in Partially Pancreatectomized DogsDocument9 pagesImpact of High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet on Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in Response to Mixed Meal in Partially Pancreatectomized DogsCatarina RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Colostomy Irrigation ProcedureDocument3 pagesColostomy Irrigation Proceduresenyorakath0% (1)

- Case Study (Summer)Document30 pagesCase Study (Summer)dave del rosarioNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Risks of SterilizationDocument29 pagesBenefits and Risks of Sterilizationvado_727No ratings yet

- TED Talk OutlineDocument3 pagesTED Talk OutlineThomas MatysikNo ratings yet

- Hospital Name N AddDocument38 pagesHospital Name N AddShruti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- WashtenawUrbanCounty2013 2017 PDFDocument170 pagesWashtenawUrbanCounty2013 2017 PDFMorgan ShatzNo ratings yet

- CMS INTERN Hopsital Directory 2012v5Document82 pagesCMS INTERN Hopsital Directory 2012v5stephjreidNo ratings yet

- Dr. Daniel SesslerDocument2 pagesDr. Daniel SesslerKimAndersonNo ratings yet

- Hospice and Palliative Care in IndiaDocument9 pagesHospice and Palliative Care in IndiaArunpv001No ratings yet

- Telemedicine 2Document13 pagesTelemedicine 2manu sethiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 43 - Do The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines WorkDocument4 pagesChapter 43 - Do The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines WorkIkhlasul Amal WellNo ratings yet

- Status and Role of AYUSH and Local Health TraditionsDocument352 pagesStatus and Role of AYUSH and Local Health TraditionsSaju_Joseph_9228100% (1)

- Murakami, Haruki - Town of Cats (New Yorker, 5 Sept 2011) PDFDocument9 pagesMurakami, Haruki - Town of Cats (New Yorker, 5 Sept 2011) PDFHanna Regine Valencerina100% (1)

- Bailey Pierson - CV 1.2020Document5 pagesBailey Pierson - CV 1.2020BaileyNo ratings yet

- Outline For Healthcare-Associated Infections Surveillance: April 2006Document8 pagesOutline For Healthcare-Associated Infections Surveillance: April 2006d_shadevNo ratings yet

- CLEAN by Juno Dawson - Opening ExcerptDocument19 pagesCLEAN by Juno Dawson - Opening ExcerptHachette KidsNo ratings yet

- Clinical FocusDocument2 pagesClinical Focuscjam20886% (7)

- Malnutrition in Acute Care Patients: A Narrative Review: Cathy Kubrak, Louise JensenDocument19 pagesMalnutrition in Acute Care Patients: A Narrative Review: Cathy Kubrak, Louise JensenchanchandilNo ratings yet

- Clinical Skill Books PDFDocument384 pagesClinical Skill Books PDFnamitaNo ratings yet

- DR Shubranshuprofile PDFDocument4 pagesDR Shubranshuprofile PDFBablu JiNo ratings yet

- Instituto Superior Tecnológico Del Transporte: Acreditado Por CACES Resolución Nro. 066-SO-07-CEAACES-2018Document7 pagesInstituto Superior Tecnológico Del Transporte: Acreditado Por CACES Resolución Nro. 066-SO-07-CEAACES-2018Jaime SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Deborah Stover RN ResumeDocument2 pagesDeborah Stover RN Resumeapi-479158a34fNo ratings yet

- BSG RPG Sister JosephineDocument4 pagesBSG RPG Sister Josephineivarpool100% (5)

- Elite - The Dark Wheel NovellaDocument43 pagesElite - The Dark Wheel NovellameNo ratings yet

- Karolinska Hospital 05 PDFDocument16 pagesKarolinska Hospital 05 PDFSaba JafriNo ratings yet

- Oncology and Basic ScienceDocument576 pagesOncology and Basic ScienceNegreanu Anca100% (1)

- Exadrop Exadrop Product Off Erings: IV Administration Set With Precision FL Ow Rate Regulator For Gravity InfusionDocument2 pagesExadrop Exadrop Product Off Erings: IV Administration Set With Precision FL Ow Rate Regulator For Gravity InfusionVignesh SubramaniamNo ratings yet

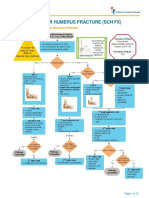

- Fracture Supracondylar HumerusDocument12 pagesFracture Supracondylar HumeruskemsNo ratings yet

- Arnold Palmer Hospital1Document3 pagesArnold Palmer Hospital1Rania Alkarmy100% (1)