Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Devi Et Al. 2014 - Nutritional Quality, Labelling and Promotion of Breakfast Cereals On The New Zealand Market

Uploaded by

Albert CalvetOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Devi Et Al. 2014 - Nutritional Quality, Labelling and Promotion of Breakfast Cereals On The New Zealand Market

Uploaded by

Albert CalvetCopyright:

Available Formats

Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Appetite

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s e v i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / a p p e t

Research report

Nutritional quality, labelling and promotion of breakfast cereals on

the New Zealand market

Anandita Devi a, Helen Eyles b, Mike Rayner c, Cliona Ni Mhurchu b, Boyd Swinburn a,d,

Emily Lonsdale-Cooper b, Stefanie Vandevijvere a,*

a

School of Population Health, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

National Institute for Health Innovation, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

c

British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

d WHO Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

b

A R T I C L E

I N F O

Article history:

Received 12 February 2014

Received in revised form 11 June 2014

Accepted 14 June 2014

Available online 19 June 2014

Keywords:

Breakfast cereals

Nutritional quality

Labelling

Claims

Promotional characters

New Zealand

A B S T R A C T

Breakfast cereals substantially contribute to daily energy and nutrient intakes among children. In New

Zealand, new regulations are being implemented to restrict nutrition and health claims to products that

meet certain healthy criteria. This study investigated the difference in nutritional quality, labelling and

promotion between healthy and less healthy breakfast cereals, and between breakfast cereals intended for children compared with other breakfast cereals on the New Zealand market. The cross-sectional

data collection involved taking pictures of the nutrition information panel (NIP) and front-of pack (FoP)

for all breakfast cereals (n = 247) at two major supermarkets in Auckland in 2013. A nutrient proling

tool was used to classify products into healthy/less healthy. In total 26% of cereals did not meet the

healthy criteria. Less healthy cereals were signicantly higher in energy density, sugar and sodium content

and lower in protein and bre content compared with healthy cereals. Signicantly more nutrition claims

(75%) and health claims (89%) featured on healthy compared with less healthy cereals. On the less healthy

cereals, nutrition claims (65%) were more predominant than health claims (17%). Of the 52 products displaying promotional characters, 48% were for cereals for kids, and of those, 72% featured on less healthy

cereals. In conclusion, most breakfast cereals met the healthy criteria; however, cereals for kids were

less healthy and displayed more promotional characters than other cereal categories. Policy recommendations include: food composition targets set or endorsed by government, strengthening and enforcing current regulations on health and nutrition claims, considering the application of nutrient proling

for nutrition claims in addition to health claims, introducing an interpretative FoP labelling system and

restricting the use of promotional characters on less healthy breakfast cereals.

2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Abbreviations: INFORMAS, International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support; FSANZ, Food Standards

Australia New Zealand; NPSC, Nutrient Proling Scoring Criterion.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge A. Chand and R. Megill for the collection of the data and R. George for contribution to data cleaning and

analysis. S. Vandevijvere and H. Eyles originated the study idea and design. H. Eyles and C. Ni Mhurchu developed the New Zealand Nutritrack database. H. Eyles provided

the nutrition information from NIP and photos of FoP for breakfast cereals from the Nutritrack database for the purposes of this study. H. Eyles and E. Lonsdale-Cooper

analysed the nutritional composition of breakfast cereals. M. Rayner developed the INFORMAS taxonomy for classifying health-related food labelling components. A. Devi

and S. Vandevijvere analysed the results on food labelling and promotion of breakfast cereals. A. Devi drafted the manuscript. S. Vandevijvere supervised the study. All authors

were involved in the interpretation of results and subsequent edits of the manuscript. This study was funded by the Faculty Research Development Fund of the University

of Auckland (Grant no. 3704413). Conict of interest: Helen Eyles holds a National Heart Foundation of New Zealand postdoctoral research fellowship (Grant 1463). The other

authors declare that they have no competing interests.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: s.vandevijvere@auckland.ac.nz (S. Vandevijvere).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.019

0195-6663/ 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

254

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Introduction

Breakfast consumption has been associated with higher bre and

calcium intakes (Barton et al., 2005), as well as a reduced risk of

becoming overweight or obese, compared with skipping breakfast

(De La Hunty, Gibson, & Ashwell, 2013; Szajewska & Ruszczynski,

2010). In New Zealand, the latest national nutrition surveys indicate that 79% of children and young people usually consume breakfast on ve or more days a week (Clinical Trials Research Unit, 2010),

and 40% of children reported eating breakfast cereals at least once

a day (Parnell, Scragg, Wilson, Schaaf, & Fitzgerald, 2003). However,

ready-to-eat (RTE) cereals tend to be highly processed (Cordain et al.,

2005) and high sugar cereals have been found to increase childrens total sugar consumption and decrease the overall nutritional quality of their breakfast (Harris, Schwartz, Ustjanauskas,

Ohri-Vachaspati, & Brownell, 2011). Additionally, breakfast cereals

marketed directly to children have been found to contain signicantly more added sugar than those marketed to adults (Schwartz,

Vartanian, Wharton, & Brownell, 2008).

High sugar RTE breakfast cereals are the most frequently promoted food products on television for child-targeted food advertising (LoDolce, Harris, & Schwartz, 2013). Promotional characters

on food packages, are also used as an attractive lure for advertising to children (Neeley & Schumann, 2004; Tang, Newton, & Wang,

2007). Licenced or spokes characters on food packages, have been

reported to inuence young childrens taste, food preferences and

purchases compared with the same products without such characters (Roberto, Baik, Harris, & Brownell, 2010; Smits & Vandebosch,

2012). It has been found that constant exposure of children to promotional characters encourages them to recognise and like the

related brands (Neeley & Schumann, 2004). On-pack nutrient content

claims and sport celebrity endorsements made pre-adolescents more

likely to choose energy-dense and nutrient-poor products and increased perceptions of their nutrient content compared with

healthier products (Dixon et al., 2014). There are currently no regulations or effective policies in place in New Zealand to reduce exposure of children to advertising of less healthy foods through any

type of medium in New Zealand.

Nutrition and health claims are regulated by the Australia New

Zealand Food Standards Code (FSC) and implemented by the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) in New Zealand (Food Standards

Australia New Zealand, 2013a, 2013b). In accordance with the FSC,

it is mandatory in New Zealand to display a nutrition information

panel (NIP) on most packaged foods (displaying energy, protein, total

fat, saturated fat, carbohydrate, sugars, and sodium per serving, and

per 100 g or 100 mL) and if nutrition claims are made, the nutrition information for that nutrient must be displayed on the NIP. A

new mandatory food standard (Standard 1.2.7) was passed in January

2013 on the regulation of nutrition and health claims on food labels

and in advertisements by the Food Standards Australia New Zealand

(FSANZ), which all food companies must comply with from 18

January 2016 (Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 2013a). This

standard aims to reduce false and misleading nutrition claims and

ensure that claims are only present on foods meeting certain healthy

criteria (Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 2013a). The healthy

criteria are set by the FSANZ Health Claims Nutrient Proling Scoring

Criterion (NPSC), a nutrient proling tool that has been tested on

more than 10,000 New Zealand and Australian food products (Food

Standards Australia New Zealand, 2007, 2013b). Currently the NPSC

only applies to foods displaying health claims and not to foods displaying nutrition claims. Using FSANZs NPSC, overall, 59% of products (n = 550) from seven food groups and 51 food categories in

supermarkets previously met the healthy criteria in New Zealand

(Eyles, Gorton, & Ni Mhurchu, 2010).

Interpretative, consumer-oriented front-of-pack (FoP) nutrition labels (Health Star Rating or trac light labelling system) have

recently been introduced in some countries to help consumers identify healthier food options (Watson et al., 2014). While Australia recently approved the voluntary implementation of the Health Star

Rating system (Australian Government Department of Health and

Ageing, 2013; Watson et al., 2014) and in the UK the Multiple Trac

Light (MTL) labelling system has also been implemented by several

retailers (United Kingdom Food Standards Agency, 2007), there is

no consumer-oriented, interpretative FoP labelling system implemented in New Zealand (Rosentreter, Eyles, & Mhurchu, 2013). Currently various industry and agency-initiated labelling systems operate

in New Zealand, which can be interpretive or non-interpretive, including the Australian Food and Grocery Councils multi-icon Daily

Intake Guide (DIG) system, individual logos and icons that relate

to a particular issue (e.g., fair trade, organic, glycaemic index (GI),

heart health) of which some are licence-based such as the GI symbol

and the Heart Foundation Tick (HF Tick) (Blewett, Goddard, Pettigrew,

Reynolds, & Yeatman, 2011; MPI Food Safety, 2013). The HF Tick aims

to allow consumers to identify healthier options within a specic

food category and encourages the food industry to reformulate and

improve nutrition quality of foods and labelling (Heart Foundation

NZ, 2013; Young & Swinburn, 2002). Approximately 500 products

currently display the DIGs thumbnails in New Zealand; however,

display of percentage dietary intake (DI) information is only mandatory for energy intake, while the use of additional percentage DI

information (fat, protein, saturated fat, carbohydrate, sugars and

sodium) is voluntary (New Zealand Food & Grocery Council).

Given the signicant contribution of breakfast cereals to childrens diet in New Zealand and the lack of strong policies on food

reformulation, labelling and promotion, the aim of this study was

to investigate the difference in nutritional quality, labelling and promotion between healthy and less healthy breakfast cereals, and

between cereals intended for children compared with other breakfast cereals on the New Zealand market.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Two of the biggest supermarkets (one representing each of the

two major chains) in Auckland, New Zealand were chosen as sites

for data collection (Countdown and PakNSave). From these supermarkets, details of all breakfast cereals available for purchase were

recorded. Where the same product was sold in more than one supermarket that product was included only once in the product

sample.

Data collection

Data collection took place from February to August 2013. A supermarket audit for breakfast cereals was conducted at each site

by two research assistants using a specially developed smart phone

application. Photos were taken of the front, side and back of all breakfast cereal packages (n = 247).

For each product the company name, product name, and barcode

were recorded. Nutrition labelling information recorded included

the HF Tick, DIG, packet size, packet unit, serving size, serving unit

and per 100 g content of energy, protein, total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates (CHO), sugar, bre (only when present) and sodium. Supermarket data were entered directly into the smartphone in the

supermarket, and exported to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel

2010). Photo and nutrient data from the NIP were entered into the

Nutritrack supermarket database, a University of Auckland branded

food and nutrient database which contains package and nutrient

information for the majority of the packaged foods for sale in NZ

supermarkets (National Institute for Health Innovation, 2011).

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Classication of products as healthy/less healthy

The FSANZ Health Claims NPSC was used to determine whether

breakfast cereals were eligible to carry a health claim. Eligible products (those meeting the NPSC) were classied as healthy and noneligible products as less healthy (Food Standards Australia New

Zealand, 2007). The criterion is based on the UK nutrient proling

model used for the regulation of TV advertising of food to children (Rayner, Scarborough, & Stockley, 2004). The NPSC provides

assessment of overall nutritional composition of a food or beverage product by rstly applying baseline points for energy, saturated fat, total sugar, and sodium content per 100 g and then applying

modifying points for dietary bre (F points), protein (P points), and

percentage of fruit and vegetable (including nuts and legumes,

coconut, spices, herbs, fungi, seeds and algae) content (V points).

A nal score is given by subtracting the modifying points from the

baseline points (baseline points (V points) (P points) (F points)).

In the case where a V or F point could not be obtained for the product

(percentage of fruit and/or vegetables or bre content not mentioned in the ingredient list or NIP), a standard V or F point was used

based on the most common percentage of fruit or vegetables or bre

content for other products in the same category (Food Standards

Australia New Zealand, 2013b). Breakfast cereals were classied as

healthy if the NPSC was less than 4 and less healthy if the NPSC

was 4 or more (Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 2013b).

Classication of health-related labelling information and

promotional characters on food packages

The standardised taxonomy, recently developed by the International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases

Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) and based

on Codex food labelling standards, was used to classify the different types of claims used on food packages (Rayner et al., 2013). Nutrition information was classied into: nutrient declarations,

supplementary nutrition information (e.g. percent Guideline Daily

Amount (GDA)), list of ingredients, and other information (e.g. origin).

Claims were classied into three categories: nutrition claims, health

claims and other claims. Nutrition claims were further categorised

into: health-related ingredient claims (e.g. contains more whole

grains) and nutrient claims. Nutrient claims were further divided

into nutrient content claims (e.g. low in fat) and, nutrient comparative claims (e.g. reduced fat). Health claims were categorised

into three categories: general health claims (e.g. healthy), nutrient and other function claims (e.g. contains calcium which is

good for your bones) and, reduction of disease risk claims (e.g. Heart

Foundation Tick). Other claims were all non-health-related claims

(e.g. organic, tasty etc.). The format of the claims was classied

into one of the following three categories: numerical, verbal or

symbolic.

Using the INFORMAS taxonomy, a number of decisions needed

to be made to classify actual labelling according to this taxonomy.

For example INFORMAS classies a claim which states, suggests or

implies that a food has particular nutritional properties by virtue

of its content of an ingredient as a health-related ingredient claim.

Therefore a claim that a breakfast cereal contained whole grain was

considered a health-related ingredient claim because it was thought

that such a claim implied that the product had particular nutritional properties. However, a claim that a breakfast cereal contained fruit such as apple or blueberries was not classied as a

health-related ingredient claim because the implication that the

product had particular nutritional properties was less clear. However,

if the amount of a particular ingredient was specied e.g. contains one of your ve fruits a day, then it was classied as a healthrelated ingredient claim because in that case there is an implication

that the food has particular nutritional properties. Classifying con-

255

tains whole grain as a health-related ingredient claim and a claim

such as contains blueberries as not was a matter of judgement.

Although energy and some antioxidants are not generally considered nutrients, claims related to energy and antioxidants were

classied as nutrient content claims. Claims in slogans were considered as general health claims if words such as goodness, nutritious or super were used to describe the product, as this was

regarded as referring to a healthy product. Due to the large and

variable number of health-related ingredient claims and nutrient

content claims, some ingredients and nutrients were merged together for analysis purposes (e.g. antioxidants/vitamins/minerals

were merged and fruits/nuts/honey were merged) to avoid too many

categories.

The promotional characters were categorised into seven types,

adapted from Hebden et al. (Hebden, King, Kelly, Chapman, &

Innes-Hughes, 2011): Cartoon/company-owned character, licenced character, amateur sportsperson, famous sportsperson, celebrity, movie tie-in and premium offers (downloads, buy one get

one free etc.) (Hebden et al., 2011). As company-owned characters were dicult to distinguish from cartoons, these were

categorised as one type (cartoon/company owned characters).

In addition to classifying breakfast cereals into healthy and less

healthy, they were also categorised into one of the following categories: Biscuits and bites (e.g. Weet-bix), brans (e.g. sultana bran),

bubble akes and puffs (e.g. corn akes), cereals for kids (e.g. Coco

Pops), muesli (e.g. toasted muesli) and oats (e.g. rolled oats),

adapted from Woods and Walker (2007) and Louie et al. (Louie,

Dunford, Walker, & Gill, 2012).

Statistical analyses

Breakfast cereal products with multiple NIPs, such as variety packs

or incomplete nutrition data were excluded from the analysis (n = 3).

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20. Independent

sample t-tests were used to compare mean values of suggested

serving size (g) and nutritional content of: healthy and less healthy

breakfast cereals, and cereals for kids vs. other categories of breakfast cereals.

Chi-square tests were used to compare the number of claims on

healthy and less healthy breakfast cereals. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically signicant. Multiple testing was not adjusted

for, but was considered in the write up and discussion of ndings.

Results

A total of 247/250 breakfast cereal products representing 30

brands had complete data (including NIP) and were included in the

analysis. Overall 182 (74%) products were classied as healthy and

65 (26%) were classied as less healthy according to the NPSC

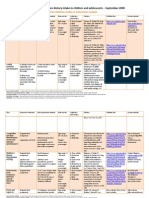

(Fig. 1).

Nutritional quality of breakfast cereals

Signicant differences (p < 0.05) were found in the nutritional

composition between healthy and less healthy breakfast cereals.

Healthy breakfast cereals on average (mean SD) were signicantly lower in energy density (1559.9 162.2 vs. 1644.5 105.1 kJ/

100 g), carbohydrate (65.7 9.1 vs. 73.5 11.5 g/100 g), sugar

(15.6 9.3 vs. 22.9 9.3 g/100 g) and sodium (142.3 142.3 vs.

338.0 223.7 mg/100 g) content and signicantly higher in protein

(10.5 2.3 vs. 9.1 4.2 g/100 g) and bre (9.7 4.2 vs. 5.2 3.2 g/

100 g) content than less healthy breakfast cereals respectively. The

percentage of healthy breakfast cereals varied across the different types of breakfast cereal categories as shown in Fig. 1. Oats was

the only category to have 100% of products classied as healthy.

256

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Percentage of breakfast cereals for sale at two Auckland

supermarkets eligible to carry a health claim (2013)

100%

58%

35%

25%

14%

90%

10%

100%

26%

90%

Percentage of breakfast cereals

80%

70%

74%

60%

50%

86%

40%

75%

65%

30%

20%

42%

10%

0%

Cereals for Bubbles,

Kids (n=36) Flakes &

Puffs

(n=65)

Muesli

(n=67)

Classified 'healthy'

Brans

(n=14)

Biscuits & Oats (n=45) All cereals

Bites (n=20)

(n=247)

Classified 'less healthy'

Fig. 1. Percentage of breakfast cereals for sale at two large Auckland supermarkets classied as healthy or less healthy (~2013). ~ Data were collected from two large

Auckland supermarkets between February and August 2013.

In contrast, 58% of cereals for kids (n = 21/36) were classied as

less healthy.

Cereals for kids had a signicantly lower mean suggested serving

size, but signicantly higher sugar and energy content compared

with most other categories of breakfast cereals. Although cereals

for kids had a lower total fat content compared with other categories of breakfast cereals (signicant for bubbles, akes and puffs,

muesli and oats only), they had a signicantly higher sodium

content compared with muesli and oats. Protein and bre content

were signicantly lower for cereals for kids compared with biscuits and bites, brans, muesli and oats. Interestingly, saturated

fat content was signicantly higher for muesli and oats compared with cereals for kids (Table 1).

Nature of claims found on breakfast cereals

Overall 238/247 (96%) breakfast cereal products displayed in total,

916 individual claims of some type on products. The maximum

Table 1

Suggested serving size and nutritional quality of breakfast cereals for kids versus other types of cereals for sale at two large Auckland supermarkets (2013).a

Suggested serving size (g)

Energy (kJ/100 g)

Protein (g/100 g)

Total fat (g/100 g)

Saturated fat (g/100 g)

Carbohydrate (g/100 g)

Sugar (g/100 g)

Fibre (g/100 g)

Sodium (mg/100 g)

Mean

SD

Min

Max

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Nb

Mean

SD

Cereals for Kids

(n = 36)

Biscuits & Bites

(n = 20)

Brans

(n = 14)

Bubbles, Flakes & Puffs

(n = 65)

Muesli

(n = 67)

Oats

(n = 45)

All cereals

(n = 247)

30.1

1.5

25

35

1608.6

37.3

8.5

4.4

2.1

1.9

0.6

0.7

79.6

6.4

26.3

10.8

4.9

2.9

32

298.4

249.9

36.4*

7.5

30

48

1500.3**

68.9

11.5**

1.2

2.3

1.9

0.9

1.2

67.6**

3.5

8.0**

8.1

10.6**

2.0

20

294.6

81.5

43.6**

4.1

30

45

1445.0**

79.3

11.0*

2.5

2.9

1.6

0.6

0.3

60.8**

10.9

21.5

6.2

17.2**

8.3

14

294.3

105.2

40.3**

8.8

25

66

1562.3

215.3

9.2

3.2

3.4*

3.6

0.7

0.8

74.4**

7.3

17.9**

8.1

6.6

3.9

61

293.3

180.6

48.8**

10.2

30

100

1682.3**

109.6

10.2*

2.0

11.4**

5.0

2.7**

1.7

60.1**

7.7

18.8**

6.1

9.0**

2.8

63

94.4**

110.9

39.7**

6.3

30

60

1520.8**

109.8

11.6**

2.3

6.1**

2.1

1.2**

0.4

62.7**

7.0

10.9**

10.6

9.5**

3.2

39

39.2**

69.8

40.9

9.8

25

100

1582.1

153.4

10.1

3.0

5.7

5.0

1.3

1.4

67.8

10.3

17.5

10.0

8.5

4.6

229

193.3

187.9

Note: SD, standard deviation. Signicantly different to corresponding mean for cereals for kids; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

a

Data were collected from two large Auckland supermarkets between February and August 2013.

b N for serving size and all nutrients except bre. Separate N for bre shown as bre is not mandatory to be displayed on Nutrition Information Panels in New Zealand.

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

257

Table 2

Different types of nutrition and health claims present on breakfast cereals for sale at two large Auckland supermarkets (2013).a

Type of claim

Content of claim

NUTRITION CLAIM

Health-related ingredient claim

Whole-grains

Fruits/nuts/honey

Grains

Nutrient claim

Nutrient content claim

Fibre

Energy

Antioxidants/vitamins/minerals

Carbohydrates

Fats

Sugar

Protein

Sodium

Cholesterol

Nutrient comparative claim

Reduced fat

More calcium

Less salt

Reduced sugar

HEALTH CLAIM

General health claim

General

Nutrient and other function claim

Protein for muscle development

Calcium for bone strength

Magnesium for growth

Reduction of disease risk claim

Heart-related

Heart foundation tick

Lowers cholesterol absorption

Glycaemic index

OTHER CLAIM

Non health-related claim

Total

Format of claim

Numerical

Verbal

Symbolic

DIG

Claims

N (%)

Breakfast cereals

total N (%)

Healthy breakfast

cereals N (%)

Less healthy breakfast

cereals N (%)

489 (53.4)

128 (26.2)

93 (72.7)

17 (13.3)

18 (14.1)

353 (72.2)

177 (71.7)

94 (53.1)

71 (75.5)

16 (17.0)

17 (18.1)

149 (84.2)

133 (73.1)

78 (58.6)

63 (80.8)

13 (16.7)

12 (15.4)

117 (88.0)

42 (64.6)

16 (38.1)

8 (50.0)

3 (18.8)

5 (31.3)

32 (76.2)

119 (33.7)

14 (4.0)

104 (29.5)

9 (2.5)

52 (14.7)

19 (5.4)

11 (3.1)

22 (6.2)

3 (0.8)

8 (1.6)

4 (50.0)

1 (12.5)

1 (12.5)

2 (25.0)

122 (13.3)

26 (21.3)

26 (100.0)

5 (4.1)

2 (40.0)

2 (40.0)

1 (20.0)

91 (74.6)

71 (78.0)

69 (75.8)

13 (14.3)

7 (7.7)

305 (33.3)

305 (100.0)

916

105 (70.5)

13 (8.7)

45 (30.2)

9 (6.0)

48 (32.2)

17 (11.4)

11 (7.4)

21 (14.1)

3 (2.0)

6 (3.4)

3 (50.0)

1 (16.7)

1 (16.7)

2 (33.3)

98 (39.7)

26 (26.5)

26 (100.0)

3 (3.1)

2 (66.7)

2 (66.7)

1 (33.3)

72 (73.7)

69 (95.8)

69 (95.8)

13 (18.1)

7 (9.7)

156 (63.2)

156 (100.0)

247

93 (79.5)

13 (11.1)

31 (26.5)

5 (4.3)

33 (28.2)

17 (14.5)

8 (6.8)

19 (16.2)

3 (2.6)

5 (3.8)

3 (60.0)

1 (20.0)

1 (20.0)

1 (20.0)

87 (47.8)

19 (21.8)

19 (100.0)

1 (1.1)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

1 (100.0)

70 (80.5)

67 (95.7)

67 (95.7)

13 (18.6)

7 (10.0)

114 (62.6)

114 (100.0)

182

12 (37.5)

0 (0.0)

14 (43.8)

4 (12.5)

15 (46.9)

0 (0.0)

3 (9.4)

2 (6.3)

0 (0.0)

1 (2.4)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

1 (100.0)

11 (16.9)

7 (63.6)

7 (100.0)

2 (18.2)

2 (100.0)

2 (100.0)

0 (0.0)

2 (18.2)

2 (100.0)

2 (100.0)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

42 (64.6)

42 (100.0)

65

122 (13.3)

688 (75.1)

106 (11.6)

97 (39.3)

218 (88.3)

99 (40.1)

130 (52.6)

21 (21.7)

162 (74.3)

87 (87.9)

90 (69.2)

76 (78.4)

56 (25.7)

12 (12.1)

40 (30.8)

Note: DIG, Dietary Intake Guide.

a

Data were collected from two large Auckland supermarkets between February and August 2013.

number of claims (including same type of claim) found on any breakfast cereal product was 14 (n = 2 products), although on average, a

product carried approximately four claims. Of the total number of

claims, 688 (75%) were verbal (n = 218 products; 88%); 122 (13%)

were numerical (n = 97 products; 39%); and 106 (12%) were symbolic (n = 99 products; 40%) claims. Of the breakfast cereals classied as less healthy, 26% (n = 56) contained verbal claims, whereas

78% (n = 76) of less healthy products contained numerical claims

(Table 2).

Nutrition claims, representing 53% of total claims, were found

on 177 (72%) products. Further categorisation of nutrition claims

showed that 26% and 72% of claims were for health-related ingredient claims (predominantly for whole grains) and nutrient content

claims respectively. Nutrient comparative claims were found on only

3% of breakfast cereal products. Health claims featured on 98 (40%)

products, and of those, 21% were general health claims; 4% were

nutrient and other function claims; and 75% were reduction of

disease risk claims (Table 2).

Overall, a signicantly higher number of healthy breakfast cereal

products carried nutrition claims (n = 133/177; 75%) and health

claims (n = 87/98; 89%) compared with less healthy breakfast cereals.

A signicantly higher number of healthy cereal products carried

health-related ingredient claims compared with less healthy products (n = 78/94; 83% vs. n = 16/94; 17% respectively). In addition, a

signicantly higher number of healthy cereal products carried reduction of disease risk claims than less healthy products (n = 70/

72; 97% vs. n = 2/72; 3% respectively) (Table 2).

Of the total number of products classied as healthy (n = 182/

247), nutrition claims featured on 73% of products and of those 59%

(n = 78) were health-related ingredient claims and 88% (n = 117) were

nutrient content claims. Of the total number of products classied

as less healthy (n = 65/247), nutrition claims featured on 65% (n = 42)

of products and they were predominantly nutrient content claims

(n = 32/42; 76%), mostly for fat and antioxidant/vitamins/minerals

respectively (n = 15/32; 47% and n = 14/32; 44%). The HF Tick (reduction of disease risk claim) was displayed on 28% (n = 69/247) of

products, of which 3% were classied less healthy. A higher proportion of less healthy breakfast cereals carried nutrition claims

compared with health claims (n = 42/65; 65% vs. n = 11/65; 17%) respectively (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, 53% (n = 130) of breakfast

cereals displayed DIG labelling, of which 69% were classied healthy.

Figure 2 shows the different types of claims found on different

categories of breakfast cereals. Bubbles, akes & puffs featured the

highest number of claims (29%), mainly nutrient content claims (111

claims), compared with other categories of breakfast cereals (data

not shown). Cereals for kids was the only category to carry nutrient and other function claims (ve claims), with more claims featuring on less healthy products (n = 4/5). Reduction of disease risk

258

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

100%

90%

Other claim

Reduction of disease

risk claim

70%

Nutrient and other

function claim

60%

50%

General health claim

40%

Nutrient

comparative claim

30%

20%

Nutrient content

claim

10%

Health-related

ingredient claim

Biscuits &

Bites (n= 20)

Brans

(n=14)

Bubbles, Cereals for

Flakes & Kids (n=36)

Puffs (n=65)

Muesli

(n=67)

Healthy

Healthy

Unhealthy

Healthy

Unhealthy

Healthy

Unhealthy

Healthy

Unhealthy

Healthy

0%

Unhealthy

Percentage of claims on breakfast cereals

80%

Oats

(n=45)

Type of breakfast cereals

Fig. 2. Percentage of claims present on healthy and less healthy breakfast cereals according to breakfast cereal type at two large Auckland supermarkets (~2013). ~ Data

were collected from two large Auckland supermarkets between February and August 2013.

claims were only present on less healthy products for brans and

bubbles, akes & puffs.

Nature of promotional characters found on breakfast cereal packages

The main types of promotional characters found on breakfast

cereal packages are presented in Table 3.

Promotional characters featured on 21% (n = 52) of breakfast

cereal products, of which 17% (n = 43) carried cartoons/licenced characters and of those, 58% of products were considered less healthy.

Amateur sportspersons were found on 3% (n = 7) of products and

of those 6/7 were classied as healthy. Of the 4% (n = 9) of products featuring premium offers, 6/9 were considered healthy. No licenced characters or celebrities or famous sportspersons were found

on breakfast cereal products. Overall, 48% (n = 25) of cereals for kids

and 35% (n = 18) of bubbles akes and puffs featured promotional characters and of those 69% and 31% were classied as less

healthy products respectively. Less healthy cereals for kids carried

a higher proportion of promotional characters (n = 18/25; 72%) compared with healthy cereals for kids (n = 7/25; 28%).

Table 3

Different types of promotional characters present on packages of breakfast cereals for sale at two large Auckland supermarkets (2013).a

Promotional characters*

Total breakfast cereals N (%)

Healthy breakfast cereals N (%)

Less healthy breakfast cereals N (%)

Cartoon/company owned character

Licenced character

Amateur sportsperson

Celebrity

Movie tie-in

Premium offers (downloads, buy 1 get 1 free etc.)

Famous sportsperson

No promotional characters

43 (17.4)

0 (0.0)

7 (2.8)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

9 (3.6)

0 (0.0)

195 (78.9)

18 (41.9)

0 (0.0)

6 (85.7)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

6 (66.7)

0 (0.0)

156 (80.0)

25 (58.1)

0 (0.0)

1 (14.3)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

3 (33.3)

0 (0.0)

39 (20.0)

Total breakfast cereals N (%)

Healthy breakfast cereals N (%)

Less healthy breakfast cereals N (%)

For products with promotional characters only (n = 52)

Cereal type

Biscuits

Brans

Bubbles, Flakes & Puffs

Cereals for Kids

Muesli

Oats

Total

3 (5.8)

1 (1.9)

18 (34.6)

25 (48.1)

3 (5.8)

2 (3.8)

52

3 (11.5)

1 (3.8)

10 (38.5)

7 (26.9)

3 (11.5)

2 (7.7)

26

a

Data were collected from two large Auckland supermarkets between February and August 2013.

* Few products carried multiple promotional characters.

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

8 (30.8)

18 (69.2)

0 (0.0)

0 (0.0)

26

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Discussion

This cross-sectional study provides an overview of the nutritional quality of breakfast cereals on the New Zealand market, as

well as on the different types of labelling information and promotional characters found on them. It is concerning that over a quarter

of breakfast cereals were classied as less healthy. The nutritional quality of less healthy breakfast cereals was signicantly lower

than that of healthy cereals, with on average signicantly lower

bre and protein content and higher energy density, and sugar and

sodium content. Our study specically raises concern regarding the

breakfast cereals intended for children as cereals for kids in general

were found to have signicantly higher energy density, sodium and

sugar content, and lower protein and bre content compared with

other categories of breakfast cereals, and 58% of cereals for kids

were classied as less healthy. These results are similar to those

found by Louie et al. for Australian breakfast cereals (Louie et al.,

2012).

The National Heart Foundation food reformulation programme

(HeartSafe (Sodium Advisory & Food Evaluation)) in New Zealand

was developed in 2010 to facilitate industry-led, cross-category

sodium reduction, based on voluntary sodium reduction targets. For

breakfast cereals the targets for sodium to be achieved by end of

2014 include 600 mg/100 g for Puffed Rice & Corn Flakes, 200 mg/

100 g for Oat-based Muesli & Porridge, and 400 mg/100 g for other

breakfast cereals (Heart Foundation NZ, 2014). This study shows that

on average these targets have been met. However, the 2017 average

sodium target in the UK for all breakfast cereals is substantially lower

at 235 mg/100 g (Food Standards Agency, 2014) and apart from the

categories muesli and oats, New Zealand breakfast cereals on

average do not meet that target. Consequently, current voluntary

sodium targets for breakfast cereals in New Zealand need to be

revised, and ideally food composition targets for sodium, sugar and

other nutrients of concern where appropriate should be informed

by international best practice and set or endorsed by the government. In addition, implementation of the health star rating system

in New Zealand, such as in Australia, should help to improve the

nutritional composition of breakfast cereals over time.

A higher proportion of nutrition and health claims on healthy

cereals in comparison with less healthy breakfast cereals was found

in our study. However, of the less healthy breakfast cereals, 65%

featured nutrition claims and 17% featured health claims. Over 40%

of the nutrient content claims on less healthy products were for

fat (e.g. low fat or fat free claims) and antioxidants/vitamins/

minerals. Such claims may mislead consumers into perceiving those

products as healthier. A 2007 FSANZ survey showed that 84% of Australians and 81% of New Zealanders mentioned food labels as their

primary source of information regarding nutritional information of

foods (Blewett et al., 2011). The mandatory NIP was found to be confusing as not being suciently visible due to small font and location of NIP, which is usually on the side or back of food products

(Jones & Richardson, 2007). Research in New Zealand has found that

the intent to purchase a product is inuenced more by high level

health claims (e.g. risk reduction claims), compared with nutrient

content and function claims. In addition, symbolic claims such

as the HF Tick were regarded as more inuential on the intent

to purchase compared with verbal claims (Mhurchu & Gorton,

2007).

Reduction of disease risk claims was the most frequent type of

health claims found in our study, especially the HF Tick (symbolic

claim), of which not all were found on healthy products.

A high number of nutrition claims were displayed on cereals

for kids and this was the only breakfast cereal category to carry

nutrient and other function claims, with a greater proportion of

such claims found on less healthy cereals for kids products (n = 4/

5). Our results are comparable with a study by Colby et al. which

259

found that 49% of all food products contained nutrition marketing

(including claims) and of those, 48% had both nutrition marketing

and were high in saturated fat, sodium and/or sugar (11%, 17%, and

31% respectively). Seventy-one percent of food products marketed to children featured nutrition marketing and of those 59%

were high in saturated fat, sodium and/or sugar content, with more

than half being high in sugar (Colby, Johnson, Scheett, & Hoverson,

2010). According to the new food standard regulating nutrition

claims and health claims on food labels and in advertisements in

New Zealand, health claims cannot be used on products classied

as less healthy according to the NPSC. However, there are no

generalised nutritional criteria that restrict the use of nutrition claims

on unhealthy foods. Since 65% of less healthy breakfast cereals

contained nutrition claims, it emphasises the importance of considering the application of the NPSC to nutrition claims in addition to health claims.

In our study no licenced characters or celebrities or famous

sportspersons were found on cereal packages, with most breakfast cereals (79%) using no promotional characters at all. These ndings are in contrast with those of an Australian study (Hebden et al.,

2011) which found 90% of breakfast cereal products featuring

company owned characters, compared with 17% of breakfast cereals

featuring cartoons and/or company owned characters in our study.

However, in this study cereals for kids featured the most promotional characters (n = 25/52; 48%) compared with other breakfast

cereal categories. Less healthy cereals for kids products carried

a much higher percentage (72%) of promotional characters than

healthy cereals for kids, especially cartoons and/or company owned

characters. These ndings are consistent with other studies which

have found promotional characters being used on packages for less

healthy products targeted to children (Hebden et al., 2011; Roberto

et al., 2010).

Studies have found that food companies use strategies with visual

appeal to attract children and build brand loyalty by frequently using

childrens favourite characters (Neeley & Schumann, 2004; Page,

Montgomery, Ponder, & Richard, 2008). Regulation and monitoring of promotional characters on food packages are necessary to restrict promotional characters on less healthy products, as dened

by the NPSC to reduce childrens exposure to them for optimal protection of their health. For instance in Ecuador, though not implemented yet, a regulation has been approved in which unhealthy food

packages are prohibited from displaying labels featuring pictures

of children, real or ctitious animal characters, or celebrities and

in Ireland, the 2005 Childrens Advertising Code states that food advertising to children under the age of 15 must not feature celebrities (World Cancer Research Fund, 2013).

A limitation of this study is that the data collected depend on

the accuracy of the NIP in regard to nutritional composition of breakfast cereals. Food manufacturers may choose to use average quantities over actual values for NIP to allow for seasonal variability and

other factors causing variations in actual values. Furthermore, there

are different methods to obtain the food composition values which

may also affect the results (Fabiansson, 2006). Only two supermarkets were included in this study for data collection; however, they

represented two large stores in New Zealands largest city and therefore it is likely that the breakfast cereals sold at those supermarkets are similar to those available elsewhere. This study has shown

concern over the current practices related to composition, labelling and promotion of breakfast cereal products and points to the

need of further studies examining other food categories. The data

are cross-sectional, but, continuous data collection through

crowdsourcing using the FoodSwitch smartphone application now

in place will allow for ongoing monitoring and evaluation of composition, labelling and promotion of food products over time

(National Institute for Health Innovation (NIHI), T.G.I.f.G.H., and Bupa

New Zealand, 2013).

260

A. Devi et al./Appetite 81 (2014) 253260

Conclusion

In conclusion, more than a quarter of breakfast cereals were classied as less healthy. It is concerning that cereals for kids were

generally less healthy and more likely to display promotional characters than other breakfast cereal categories. Although breakfast

cereal products meeting the healthy criteria were more likely to

carry nutrition and health claims, 65% of less healthy breakfast

cereals featured nutrition claims and 17% featured health claims.

These ndings suggest that other food categories need to be examined as well. Policy recommendations based on the results of this

study include: food composition targets set or endorsed by government, enforcing and strengthening current regulations on health

and nutrition claims, applying the nutrient proling tool to nutrition claims in addition to health claims, introducing an evidencebased, interpretative FoP labelling system and restricting the use

of promotional characters on less healthy breakfast cereals.

References

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (2013). Front-of-pack

labelling updates. Available from <http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/

publishing.nsf/Content/foodsecretariat-front-of-pack-labelling-1> Last accessed

09.01.14.

Barton, B. A., Eldridge, A. L., Thompson, D., Affenito, S. G., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Franko,

D. L., et al. (2005). The relationship of breakfast and cereal consumption to

nutrient intake and body mass index. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood

Institute Growth and Health Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association,

105(9), 13831389.

Blewett, N., Goddard, N., Pettigrew, S., Reynolds, C., & Yeatman, H. (2011). Labelling

logic. Review of food labelling law and policy. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia.

Clinical Trials Research Unit (2010). A national survey of children and young peoples

physical activity and dietary behaviours in New Zealand: 2008/09. Key Findings.

Auckland, New Zealand: The University of Auckland.

Colby, S. E., Johnson, L., Scheett, A., & Hoverson, B. (2010). Nutrition marketing on

food labels. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(2), 9298.

Cordain, L., Eaton, S. B., Sebastian, A., Mann, N., Lindeberg, S., Watkins, B. A., et al.

(2005). Origins and evolution of the Western diet. Health implications for the

21st century. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 81(2), 341354.

De La Hunty, A., Gibson, S., & Ashwell, M. (2013). Does regular breakfast cereal

consumption help children and adolescents stay slimmer? A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Obesity Facts, 6(1), 7085.

Dixon, H., Scully, M., Niven, P., Kelly, B., Chapman, K., Donovan, R., et al. (2014). Effects

of nutrient content claims, sports celebrity endorsements and premium offers

on pre-adolescent childrens food preferences. Experimental research. Pediatric

Obesity, 9(2), e47e57.

Eyles, H., Gorton, D., & Ni Mhurchu, C. (2010). Classication of healthier and less

healthy supermarket foods by two Australasian nutrient proling models. The

New Zealand Medical Journal, 123(1322), 820.

Fabiansson, S. U. (2006). Precision in nutritional information declarations on food

labels in Australia. Asia Pacic Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 15(4), 451458.

Food Standards Agency (2014). 2017 UK salt reduction targets. Available from

<http://www.food.gov.uk/scotland/scotnut/salt/saltreduction> Last accessed

05.05.14.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (2007). Calculation method for determining

foods eligible to make health claims. Nutrient proling calculator. Canberra, Food

Standards Australia New Zealand.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (2013a). Nutrition content claims and health

claims. Available from <http://www.foodstandards.govt.nz/consumer/labelling/

nutrition/Pages/default.aspx> Last accessed 16.10.13.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (2013b). Short guide for industry to the nutrient

proling scoring criterion (NPSC) in standard 1.2.7. Nutrition, health and related

claims. Canberra, Food Standards Australia New Zealand.

Harris, J. L., Schwartz, M. B., Ustjanauskas, A., Ohri-Vachaspati, P., & Brownell, K. D.

(2011). Effects of serving high-sugar cereals on childrens breakfast-eating

behavior. Pediatrics, 127(1), 7176.

Heart Foundation NZ (2013). About the Tick. Available from <http://www

.heartfoundation.org.nz/healthy-living/healthy-eating/heart-foundation-tick/

what-is-the-tick> Last accessed 23.10.13.

Heart Foundation NZ (2014). HeartSAFE. Available from <http://

www.heartfoundation.org.nz/programmes-resources/food-industry-andhospitality/heartsafe> Last accessed 01.05.14.

Hebden, L., King, L., Kelly, B., Chapman, K., & Innes-Hughes, C. (2011). A menagerie

of promotional characters. Promoting food to children through food packaging.

Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 43(5), 349355.

Jones, G., & Richardson, M. (2007). An objective examination of consumer perception

of nutrition information based on healthiness ratings and eye movements. Public

Health Nutrition, 10(3), 238244.

LoDolce, M. E., Harris, J. L., & Schwartz, M. B. (2013). Sugar as part of a balanced

breakfast? What cereal advertisements teach children about healthy eating.

Journal of Health Communication, 18(11), 12931309.

Louie, J. C. Y., Dunford, E. K., Walker, K. Z., & Gill, T. P. (2012). Nutritional quality of

Australian breakfast cereals. Are they improving? Appetite, 59(2), 464470.

Mhurchu, C. N., & Gorton, D. (2007). Nutrition labels and claims in New Zealand and

Australia. A review of use and understanding. Australian and New Zealand Journal

of Public Health, 31(2), 105112.

MPI Food Safety (2013). Food labelling. Available from <http://www

.foodsmart.govt.nz/whats-in-our-food/food-labelling/> Last accessed 23.01.14.

National Institute for Health Innovation (2011). Nutritrack. Reformulation of processed

foods to promote health. Available from <http://www.nihi.auckland.ac.nz/page/

current-research/our-nutrition-and-physical-activity-research/nutritrackreformulation-processe> Last accessed 21.01.14.

National Institute for Health Innovation (NIHI), T.G.I.f.G.H., and Bupa New Zealand

(2013). FoodSwitch. Available from <http://www.foodswitch.co.nz/> Last accessed

10.04.14.

Neeley, S. M., & Schumann, D. W. (2004). Using animated spokes-characters in

advertising to young children. Does increasing attention to advertising necessarily

lead to product preference? Journal of Advertising, 33(3), 723.

New Zealand Food & Grocery Council. Daily intake labelling scheme. Available from

<http://www.fgc.org.nz/education/daily-intake-labelling-scheme> Last accessed

22.10.13.

Page, R., Montgomery, K., Ponder, A., & Richard, A. (2008). Targeting children in the

cereal aisle. Promotional techniques and content features on ready-to-eat

cereal product packaging. American Journal of Health Education, 39(5),

272282.

Parnell, W., Scragg, R., Wilson, N., Schaaf, D., & Fitzgerald, E. (2003). NZ food NZ children.

Key results of the 2002 national childrens nutrition survey. Wellington, New

Zealand: Ministry of Health.

Rayner, M., Scarborough, P., & Stockley, L. (2004). Nutrient proles. Options for

denitions for use in relation to food promotion and childrens diets. London, United

Kingdom: British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group,

Department of Public Health.

Rayner, M., Wood, A., Lawrence, M., Mhurchu, C. N., Albert, J., Barquera, S., et al. (2013).

Monitoring the health-related labelling of foods and non-alcoholic beverages in

retail settings. Obesity Reviews, 14(S1), 7081.

Roberto, C. A., Baik, J., Harris, J. L., & Brownell, K. D. (2010). Inuence of licensed

characters on childrens taste and snack preferences. Pediatrics, 126(1),

8893.

Rosentreter, S. C., Eyles, H., & Mhurchu, C. N. (2013). Trac lights and health claims.

A comparative analysis of the nutrient prole of packaged foods available for

sale in New Zealand supermarkets. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public

Health, 37(3), 278283.

Schwartz, M. B., Vartanian, L. R., Wharton, C. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2008). Examining

the nutritional quality of breakfast cereals marketed to children. Journal of the

American Dietetic Association, 108(4), 702705.

Smits, T., & Vandebosch, H. (2012). Endorsing childrens appetite for healthy

foods. Celebrity versus non-celebrity spokes-characters. Communications, 37(4),

371391.

Szajewska, H., & Ruszczynski, M. (2010). Systematic review demonstrating that

breakfast consumption inuences body weight outcomes in children and

adolescents in Europe. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 50(2),

113119.

Tang, T., Newton, G. D., & Wang, X. (2007). Does synergy work? An examination of

cross-promotion effects. International Journal on Media Management, 9(4),

127134.

United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (2007). Front of pack nutritional signpost

labelling technical guide (Issue 2). London (UK), Food Standards Agency.

Watson, W. L., Kelly, B., Hector, D., Hughes, C., King, L., Crawford, J., et al. (2014). Can

front-of-pack labelling schemes guide healthier food choices? Australian shoppers

responses to seven labelling formats. Appetite, 72, 9097.

Woods, J., & Walker, K. (2007). Choosing breakfast. How well does packet information

on Australian breakfast cereals, bars and drinks reect recommendations?

Nutrition and Dietetics, 64(4), 226233.

World Cancer Research Fund (2013) WCRF International Food Policy Framework for

Healthy Diets: NOURISHING. Available from <http://www.wcrf.org/policy_public

_affairs/nourishing_framework/food_marketing_advertising> Last accessed

14.04.14.

Young, L., & Swinburn, B. (2002). Impact of the Pick the Tick food information

programme on the salt content of food in New Zealand. Health Promotion

International, 17(1), 1319.

You might also like

- Natural Bodybuilding Competition Preparation and Recovery - A 12-Month Case StudyDocument11 pagesNatural Bodybuilding Competition Preparation and Recovery - A 12-Month Case StudyRodrigo Castillo100% (1)

- The Meat Buyer's GuideDocument339 pagesThe Meat Buyer's Guideskoiper100% (11)

- Vegetarian Diet Safety During Pregnancy Meta-AnalysisDocument41 pagesVegetarian Diet Safety During Pregnancy Meta-AnalysisyuliaNo ratings yet

- Cho Gao Franchise BrochureDocument9 pagesCho Gao Franchise BrochureFranchise Middle EastNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Flavor BookDocument74 pagesTobacco Flavor BookJohn Leffingwell100% (2)

- McDonald's Resource Use and Benefits to NZ EconomyDocument13 pagesMcDonald's Resource Use and Benefits to NZ EconomyQue Sab100% (2)

- Retail Management and Consumer Perception in Haldiram Snack PVT LTD - Suchit GargDocument81 pagesRetail Management and Consumer Perception in Haldiram Snack PVT LTD - Suchit GargTarunAggarwal50% (2)

- Nutrition and Health Claims On Healthy and Less Healthy Packaged Food Products in New ZealandDocument8 pagesNutrition and Health Claims On Healthy and Less Healthy Packaged Food Products in New ZealandKastuNo ratings yet

- Nurturing a Healthy Generation of Children: Research Gaps and Opportunities: 91st Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Manila, March 2018From EverandNurturing a Healthy Generation of Children: Research Gaps and Opportunities: 91st Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Manila, March 2018No ratings yet

- Nutrient Intake Milk RestrictedDocument7 pagesNutrient Intake Milk RestrictedfffreshNo ratings yet

- 12 Chapter 2Document41 pages12 Chapter 2Christine HalamaniNo ratings yet

- Kids Australia - Dietary GuideDocument444 pagesKids Australia - Dietary GuideDaria ThomasNo ratings yet

- Led To A Reduction in Salt OvernightDocument1 pageLed To A Reduction in Salt OvernightHannah VueltaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 04 01958Document19 pagesNutrients 04 01958Wahyu Arief MahatmaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Dietetics - 2008 - HENDRIE - Validation of The General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in An AustralianDocument6 pagesNutrition Dietetics - 2008 - HENDRIE - Validation of The General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in An AustralianEndah FujiNo ratings yet

- A Community-Based Positive Deviance PDFDocument9 pagesA Community-Based Positive Deviance PDFApril ApriliantyNo ratings yet

- The Australian Guide To Healthy Eating A Teacher's GuideDocument20 pagesThe Australian Guide To Healthy Eating A Teacher's GuideWaris RobleNo ratings yet

- AC Sal 2012Document7 pagesAC Sal 2012Genesis VelizNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Marketing Strategy, Serving Size, and Nutrition Information of Popular Children's Food Packages in TaiwanDocument14 pagesNutrients: Marketing Strategy, Serving Size, and Nutrition Information of Popular Children's Food Packages in TaiwangaurdevNo ratings yet

- Ultraprocessed Family Foods in Australia Nutrition Claims Health Claims and Marketing Techniques PDFDocument11 pagesUltraprocessed Family Foods in Australia Nutrition Claims Health Claims and Marketing Techniques PDFSarah SofiaNo ratings yet

- Child BearingDocument11 pagesChild BearingMel MattNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 00657 v6Document19 pagesNutrients 13 00657 v6Hieu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Rephrase Research PaperDocument57 pagesRephrase Research PaperLa YannaNo ratings yet

- Child Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesChild Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderspedroNo ratings yet

- The Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityDocument4 pagesThe Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityEMMANUELNo ratings yet

- Fast FoodDocument8 pagesFast Foodkangna_sharma20No ratings yet

- Moringa OleiferaDocument20 pagesMoringa OleiferaAjay DNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Package Attributes On Consumer Perception at The Market With Healthy FoodDocument8 pagesThe Influence of Package Attributes On Consumer Perception at The Market With Healthy FoodYash KothariNo ratings yet

- Study of Early Complementary Feeding Determinants in The Republic of Ireland Based On A Crosssectional Analysis of The Growing Up in Ireland Infant CohortDocument11 pagesStudy of Early Complementary Feeding Determinants in The Republic of Ireland Based On A Crosssectional Analysis of The Growing Up in Ireland Infant CohortArina Nurul IhsaniNo ratings yet

- Megan Rollo ThesisDocument10 pagesMegan Rollo Thesistinamclellaneverett100% (1)

- The Effect of Thickened-Feed Interventions On Gastroesophageal RefluxDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Thickened-Feed Interventions On Gastroesophageal Refluxminerva_stanciuNo ratings yet

- The Degree of Food Processing Contributes To SugarDocument11 pagesThe Degree of Food Processing Contributes To Sugart.elgammal188No ratings yet

- Nutrition Now - Enhancing Nutritional Care - RCNDocument36 pagesNutrition Now - Enhancing Nutritional Care - RCNNeha BhartiNo ratings yet

- 308-Article Text-890-2-10-20200529Document10 pages308-Article Text-890-2-10-20200529Jonah reiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0195666318313412 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0195666318313412 MainRomane AracenaNo ratings yet

- Chapter One - ThreeDocument26 pagesChapter One - ThreeSamson ikenna OkonkwoNo ratings yet

- FullFood EPIreport1Document93 pagesFullFood EPIreport1Brayam AguilarNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and attitudes towards baby-led weaningDocument7 pagesKnowledge and attitudes towards baby-led weaningmyjesa07No ratings yet

- Appetite: Pernilla Sandvik, Margaretha Nydahl, Iwona Kihlberg, Ingela MarklinderDocument9 pagesAppetite: Pernilla Sandvik, Margaretha Nydahl, Iwona Kihlberg, Ingela MarklinderahlemNo ratings yet

- Are School Meals A Viable and Sustainable Tool To Improve The Healthiness and Sustainability of Children S Diet and Food Consumption A Cross NationalDocument18 pagesAre School Meals A Viable and Sustainable Tool To Improve The Healthiness and Sustainability of Children S Diet and Food Consumption A Cross NationalAndreia BorgesNo ratings yet

- AderemiAV FoodAdditiveDocument13 pagesAderemiAV FoodAdditivePamela Alexandra MañayNo ratings yet

- Baby-Led Weaning The Evidence To DateDocument9 pagesBaby-Led Weaning The Evidence To DateCristopher San MartínNo ratings yet

- Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Consumer Behavior Intervention To Improve Healthy Food Purchases From Online Canteens PDFDocument10 pagesCluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Consumer Behavior Intervention To Improve Healthy Food Purchases From Online Canteens PDFHUYỀN BÙI THỊNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument10 pagesResearchGildred Rada BerjaNo ratings yet

- MR ResearchPaperDocument13 pagesMR ResearchPaperTushar Guha NeogiNo ratings yet

- Duration of Breastfeeding, But Not Timing of Solid Food, Reduces The Risk of Overweight and Obesity in Children Aged 24 To 36 Months: Findings From An Australian Cohort StudyDocument14 pagesDuration of Breastfeeding, But Not Timing of Solid Food, Reduces The Risk of Overweight and Obesity in Children Aged 24 To 36 Months: Findings From An Australian Cohort StudyLuciana MacedoNo ratings yet

- Early Years Menus Part 1 GuidanceDocument53 pagesEarly Years Menus Part 1 GuidanceAndreea AndreiNo ratings yet

- Diet Assessment ToolDocument3 pagesDiet Assessment Toolme_sushmadahalNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyGita Fajar WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Improved Nutrition Delivery and Nutrition Status in Critically Ill Children With Heart DiseaseDocument9 pagesImproved Nutrition Delivery and Nutrition Status in Critically Ill Children With Heart DiseasedaindesNo ratings yet

- Association of Infant Feeding Practices and Food NDocument11 pagesAssociation of Infant Feeding Practices and Food NBULAN IFTINAZHIFANo ratings yet

- STAMP (Kids)Document8 pagesSTAMP (Kids)Rika LedyNo ratings yet

- DumppppDocument4 pagesDumppppClarissa MorteNo ratings yet

- Development of Menu Planning Resources For Child Care Centres: A Collaborative ApproachDocument7 pagesDevelopment of Menu Planning Resources For Child Care Centres: A Collaborative ApproachKeanna Maxine MaestroNo ratings yet

- Science Our Food Supply: Using The To Make Healthy Food ChoicesDocument72 pagesScience Our Food Supply: Using The To Make Healthy Food Choiceslaarni malataNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0195666316305645 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0195666316305645 MainCaritoSanchezNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 14 00892Document23 pagesNutrients 14 00892TRABAJOS DR. MÜSEL TABARESNo ratings yet

- Breast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsDocument9 pagesBreast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsBernadette Grace RetubadoNo ratings yet

- PYMS Is A Reliable Malnutrition Screening ToolsDocument8 pagesPYMS Is A Reliable Malnutrition Screening ToolsRika LedyNo ratings yet

- Association of Energy Intake and Physical Activity With OverweighDocument6 pagesAssociation of Energy Intake and Physical Activity With OverweighArdanNo ratings yet

- Thornley Et Al 2020 Fatores Associados ECC Coorte IJPDDocument26 pagesThornley Et Al 2020 Fatores Associados ECC Coorte IJPDNajara RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Feeding ArvedsonDocument10 pagesFeeding ArvedsonPablo Oyarzún Dubó100% (1)

- Good Food Choices May 2021 For WebDocument45 pagesGood Food Choices May 2021 For WebCristina RamosNo ratings yet

- MANS food consumption patterns under 40 charsDocument15 pagesMANS food consumption patterns under 40 charsd-fbuser-39241155No ratings yet

- Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary DiversityFrom EverandGuidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary DiversityNo ratings yet

- Human Milk: Composition, Clinical Benefits and Future Opportunities: 90th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Lausanne, October-November 2017From EverandHuman Milk: Composition, Clinical Benefits and Future Opportunities: 90th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Lausanne, October-November 2017No ratings yet

- Markel 2011 - The Resurgence of Niacin, From Nicotinic Acid To NiaspanlaropiprantDocument7 pagesMarkel 2011 - The Resurgence of Niacin, From Nicotinic Acid To NiaspanlaropiprantAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Dirlewanger Et Al. 2000 - Effects of Short-Term Carbohydrate or Fat Overfeeding On EE and Plasma Leptin Concentrations in Healhy Female SubjectsDocument6 pagesDirlewanger Et Al. 2000 - Effects of Short-Term Carbohydrate or Fat Overfeeding On EE and Plasma Leptin Concentrations in Healhy Female SubjectsAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Deepak Et Al. 2003 - Heart Rate Recovery After Exercise Is A Predictor of Mortality, Independent of The Angiographic Severity of Coronary DiseaseDocument8 pagesDeepak Et Al. 2003 - Heart Rate Recovery After Exercise Is A Predictor of Mortality, Independent of The Angiographic Severity of Coronary DiseaseAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Tremblay Et Al. 2012 - Adaptive Thermogenesis Can Make A Difference in The Ability of Obese Individuals To Lose Body WeightDocument6 pagesTremblay Et Al. 2012 - Adaptive Thermogenesis Can Make A Difference in The Ability of Obese Individuals To Lose Body WeightAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Astrup Et Al. 2015 - The Role of Higher Protein Diets in Weight Control and Obesity-Related ComorbiditiesDocument6 pagesAstrup Et Al. 2015 - The Role of Higher Protein Diets in Weight Control and Obesity-Related ComorbiditiesAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Helms Et Al. 2014 - A Systematic Review of Dietary Protein During Caloric Restriction in Resistance Trained Lean AthletesDocument13 pagesHelms Et Al. 2014 - A Systematic Review of Dietary Protein During Caloric Restriction in Resistance Trained Lean AthletesAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Menon Et Al. 2015 - Cooking Behavior and Starch Digestibility of NUTRIOSE® (Resistant Starch) Enriched Noodles From Sweet Potato Flour and StarchDocument8 pagesMenon Et Al. 2015 - Cooking Behavior and Starch Digestibility of NUTRIOSE® (Resistant Starch) Enriched Noodles From Sweet Potato Flour and StarchAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Artigo Fast Food X Suplementos Hailes - Ijsnem - 2014-0230-In PressDocument24 pagesArtigo Fast Food X Suplementos Hailes - Ijsnem - 2014-0230-In PresshenriquecrgNo ratings yet

- Artigo Fast Food X Suplementos Hailes - Ijsnem - 2014-0230-In PressDocument24 pagesArtigo Fast Food X Suplementos Hailes - Ijsnem - 2014-0230-In PresshenriquecrgNo ratings yet

- Okuyama Et Al. 2015 - Statins Stimulate Atherosclerosis and Heart Failure, Pharmacological MechanismsDocument11 pagesOkuyama Et Al. 2015 - Statins Stimulate Atherosclerosis and Heart Failure, Pharmacological MechanismsAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Stohs Et Al. 2012 - A Review of The Human Clinical Studies Involving Citrus Aurantium (Bitter Orange) Extract...Document12 pagesStohs Et Al. 2012 - A Review of The Human Clinical Studies Involving Citrus Aurantium (Bitter Orange) Extract...Albert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Saiyed Et Al. 2015 - Safety and Toxicological Evaluation of Meratrim, An Herbal Formulation For Weight ManagementDocument8 pagesSaiyed Et Al. 2015 - Safety and Toxicological Evaluation of Meratrim, An Herbal Formulation For Weight ManagementAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Boudou Et Al. 2003 - Absence of Exercise-Induced Variations in Adiponectin Levels Despite Decreased Abdominal Adiposity and Improve IR in T2DM - 421.fullDocument4 pagesBoudou Et Al. 2003 - Absence of Exercise-Induced Variations in Adiponectin Levels Despite Decreased Abdominal Adiposity and Improve IR in T2DM - 421.fullAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Tremblay Et Al. 2012 - Adaptive Thermogenesis Can Make A Difference in The Ability of Obese Individuals To Lose Body WeightDocument6 pagesTremblay Et Al. 2012 - Adaptive Thermogenesis Can Make A Difference in The Ability of Obese Individuals To Lose Body WeightAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- 7Document7 pages7Christine FrancisNo ratings yet

- Twenty-Five Milligrams of Clomiphene Citrate Presents Positive Effect On Treatment of Male Testosterone Deficiency - A Prospective StudyDocument7 pagesTwenty-Five Milligrams of Clomiphene Citrate Presents Positive Effect On Treatment of Male Testosterone Deficiency - A Prospective StudyAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Golay Et Al. 2000 - Similar Weight Loss With Low-Energy Food Combining or Balanced DietsDocument5 pagesGolay Et Al. 2000 - Similar Weight Loss With Low-Energy Food Combining or Balanced DietsAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Effect SimvastatinDocument4 pagesEffect SimvastatinMario AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Choo Et Al. 2015 - The Ecologic Validity of Fructose Feeding Trials, Supraphyysiological Feeding of Fructose in Human Trials Requires Careful ConsiderationDocument12 pagesChoo Et Al. 2015 - The Ecologic Validity of Fructose Feeding Trials, Supraphyysiological Feeding of Fructose in Human Trials Requires Careful ConsiderationAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Galani Et Al. 2010 - Sphaeranthus Indicus Linn. A Phytopharmacological ReviewDocument14 pagesGalani Et Al. 2010 - Sphaeranthus Indicus Linn. A Phytopharmacological ReviewAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Paoli 2014 - Ketogenic Diet For Obesity Friend or Foe - Ijerph-11-02092Document16 pagesPaoli 2014 - Ketogenic Diet For Obesity Friend or Foe - Ijerph-11-02092Albert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Schaafsma 2008 - Lactose and Lactose Derivatives As Bioactive Ingredients in Human NutritionDocument9 pagesSchaafsma 2008 - Lactose and Lactose Derivatives As Bioactive Ingredients in Human NutritionAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Role of Zinc in A Rat Model of EpilepsyDocument7 pagesInvestigating The Role of Zinc in A Rat Model of EpilepsyAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Jovanovski Et Al. 2015 - Effect of Spinach, A High Dietary Nitrate Source, On Arterial Stiffness and Related Hemodynamic Measures, A RCTDocument8 pagesJovanovski Et Al. 2015 - Effect of Spinach, A High Dietary Nitrate Source, On Arterial Stiffness and Related Hemodynamic Measures, A RCTAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Sumithran Et Al. 2013 - The Defence of Body Weight, A Physiological Basis For Weight Regain After Weight LossDocument11 pagesSumithran Et Al. 2013 - The Defence of Body Weight, A Physiological Basis For Weight Regain After Weight LossAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Rosner 2015 - Preventing Deaths Due To Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, The 2015 Consensus GuidelinesDocument2 pagesRosner 2015 - Preventing Deaths Due To Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, The 2015 Consensus GuidelinesAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Coupé & Bouret 2012 - Weighing On Autophagy, A Novel Mechanism For The CNS Regulation of Energy BalanceDocument2 pagesCoupé & Bouret 2012 - Weighing On Autophagy, A Novel Mechanism For The CNS Regulation of Energy BalanceAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- A Periodic Diet That Mimics Fasting Promotes Multi-System Regeneration, Enhanced Cognitive Performance, and HealthspanDocument15 pagesA Periodic Diet That Mimics Fasting Promotes Multi-System Regeneration, Enhanced Cognitive Performance, and HealthspanvinayksNo ratings yet

- Bishop-Bailey 2013 - Mechanisms Governing The Health and Performance Benefits of Exercise, ReviewDocument14 pagesBishop-Bailey 2013 - Mechanisms Governing The Health and Performance Benefits of Exercise, ReviewAlbert CalvetNo ratings yet

- Parle Official Website: Creativeland Asia Adds Mother S Love in New Hippo TVCDocument23 pagesParle Official Website: Creativeland Asia Adds Mother S Love in New Hippo TVCShubhangi SarafNo ratings yet

- Super Science ExperimentsDocument76 pagesSuper Science Experimentsnurain100% (1)

- Cola Offensives Drive Expansion of India Market)Document12 pagesCola Offensives Drive Expansion of India Market)xingabcdNo ratings yet

- Food/Feed Laboratory Accreditation Best PracticesDocument56 pagesFood/Feed Laboratory Accreditation Best PracticesMochamad BaihakiNo ratings yet

- CHM Project ReportDocument23 pagesCHM Project ReportAvinash KumarNo ratings yet

- Farm Ponds For Water, Fish and LivelihoodsDocument74 pagesFarm Ponds For Water, Fish and LivelihoodsSandra MianNo ratings yet

- UnileverDocument14 pagesUnileverManish PandeyNo ratings yet

- Iso 22ooo Food Safety Management SystemDocument58 pagesIso 22ooo Food Safety Management SystemmmammerNo ratings yet

- Why Invest in Sofitel - Accor Global Development - FEB19Document35 pagesWhy Invest in Sofitel - Accor Global Development - FEB19maureen sullivanNo ratings yet

- Swarovski Advanced Crystal CPSIADocument6 pagesSwarovski Advanced Crystal CPSIAenkiltpeNo ratings yet

- Distributor Catalog 2020Document21 pagesDistributor Catalog 2020Nilesh SalunkeNo ratings yet

- My Time Dining: Now Available To Pre-Reserve OnlineDocument1 pageMy Time Dining: Now Available To Pre-Reserve OnlineJuan Guillermo MartinezNo ratings yet

- Tanguy GEORIS: Business Unit Director Food BeneluxDocument3 pagesTanguy GEORIS: Business Unit Director Food BeneluxBruno TeotonioNo ratings yet

- Amtrak Dining RFPDocument54 pagesAmtrak Dining RFPdgabbard2No ratings yet

- When Is Your BirthdayDocument5 pagesWhen Is Your BirthdayDanilo BastidasNo ratings yet

- Recipes From The Lee Bros. Charleston KitchenDocument13 pagesRecipes From The Lee Bros. Charleston KitchenThe Recipe Club100% (5)

- ĐỀ THI DUYÊN HẢI LỚP 10Document11 pagesĐỀ THI DUYÊN HẢI LỚP 10linh1652002100% (1)

- Porters Five Force Model: Bargaining Power To Supplier (LIMITED)Document4 pagesPorters Five Force Model: Bargaining Power To Supplier (LIMITED)yash chauhanNo ratings yet

- Company Profile, Structure and Marketing Mix of Britannia IndustriesDocument27 pagesCompany Profile, Structure and Marketing Mix of Britannia IndustriesJanardhanamurthy JanardhanNo ratings yet

- 01Document11 pages01students007No ratings yet

- Long Term Visibility Template 3.0 - Britannia v2Document1 pageLong Term Visibility Template 3.0 - Britannia v2Sripathy ChandrasekarNo ratings yet

- Holidays Homework For IX X XIIDocument7 pagesHolidays Homework For IX X XIIparbishiNo ratings yet

- KFCDocument20 pagesKFCSaadia SaeedNo ratings yet

- Hourly Earnings in March, 1994 Index 100 Hourly Earnings in 1980Document11 pagesHourly Earnings in March, 1994 Index 100 Hourly Earnings in 1980SANIUL ISLAMNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis - Boston PizzaDocument19 pagesNeeds Analysis - Boston PizzaRavi KataniNo ratings yet