Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vermeer's Clients & Patrons

Uploaded by

Joe MagilCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vermeer's Clients & Patrons

Uploaded by

Joe MagilCopyright:

Available Formats

Vermeer's Clients and Patrons

Author(s): John Michael Montias

Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp. 68-76

Published by: College Art Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051083 .

Accessed: 14/04/2011 19:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art

Bulletin.

http://www.jstor.org

Vermeer'sClients and Patrons

John Michael Montias

On the basis of newly discovered documents, this article establishes with a high

degree of probability that Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven was Vermeer's patron

throughout most of his career. He lent Vermeer200 guilders in 1657; his wife left

the artist a conditional bequest of 500 guilders in her testament of 1665; he witnessed the testament of Vermeer'ssister Gertruy in 1670. There were twenty paintings by Vermeerin the estate of Van Ruijven's only daughter and heir, Magdalena,

which she owned jointly with her husband, Jacob Dissius. The division of the estate

in 1685 shows that paintings by Emanuel de Witte, Simon de Vlieger, and Vermeer,

which had probably been acquired by Pieter van Ruijven, were allotted to Jacob

Dissius' father, Abraham. After Abraham's death these paintings reverted to his

son Jacob. The backgrounds and collections of other contemporary clients of Vermeer, including the baker Hendrick van Buyten, are briefly discussed. Finally, it

is conjectured that Vermeer had access to Leyden collectors and artists via his

patron Van Ruijven.

Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven

It has long been known that Gerard Dou and his pupil Frans

van Mieris, who preceded Vermeer in the art of "fine painting," sold the bulk of their paintings to a few preferred

collectors who may be considered their patrons.1 From circumstantial evidence, which I think the reader will find

compelling, I will show that Vermeer also had a patron,

named Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, during the greater part

of his career. Van Ruijven lent Vermeer money and his wife

left him a bequest in her testament. Van Ruijven was the

father-in-law of Jacob Dissius in whose collection

Abraham Bredius found nineteen paintings by Vermeer a

century ago.2

Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven was a first cousin of Jan Hermansz. van Ruijven who married Christina Delff, the sister

of the painter Jacob Delff and the granddaughter of Michiel

van Miereveld.3 Jan Hermansz.'s grandfather, Pieter Joostensz. van Ruijven, having sided with the Remonstrants

during the Oldenbarnevelt episode of 1618, was barred by

Stadhouder Maurits from appointment to any higher state

or municipal functions. It is probable that Pieter Claesz.

himself, like other members of his family, was a Remonstrant. His father, Niclaes Pietersz. van Ruijven, was a

brewer in "The Ox" brewery and a master of Delft's Camer

van Charitate (in 1623 and 1624). His mother, Maria Graswinckel, the daughter of Cornelis Jansz. Graswinckel and

Sara Mennincx, belonged to one of the most distinguished

of Delft's old patrician families. Two of Sara Mennincx's

sisters, Maria and Oncommera, were married in succession

to Franchois Spierinx, the famous tapestry-maker of Flemish origin who settled in Delft some time before 1600. The

son of Franchois Spierinx and Oncommera Mennincx,

named Pieter Spierincx Silvercroon, became Sweden's envoy to Holland. It was this same Pieter Spierincx who paid

Gerard Dou an annual fee of 500 guilders in the late 1630'sto

secure the right of first refusal on one painting per year.4

Dou's patron was thus the son of Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven's great-aunt. He was also the godfather of Pieter

Claesz.'s sister Pieternella who was baptized in the New

Church in Delft on 9 May 16425when Pieter Claesz. was

eighteen years old. Living as he did in his parents' household, he could not have failed to meet his mother's first

1 All documents about Vermeer

published before 1977 that are referred

to in this article are summarized in Blankert. The dates of Vermeer'spaintings cited in the text are from this source and from Wheelock. In revising

this article, I benefited from the comments of Professor Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann.

2 Abraham Bredius, "Ietsover Johannes Vermeer,"Oud-Holland, III, 1885,

222. There were actually twenty paintings by Vermeer in the Dissius Collection, as discussed below.

3The genealogy of Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven is traced in Nederlandsche

leeuw, LXXXVII,

1970, 101-04. I owe this reference to Mr. W.A. Wijburg,

who has been able to establish that Vermeer'swife, Catharina Bolnes, and

Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven were distantly related. To be precise, Adriaen

Cool, who was the son of Catharina Bolnes's great-grandaunt Maria Geenen, had married Erckenraad Duyst van Voorhoudt, who was the great-

granddaughter of Hendrick Duyst (d. 1530). The brother of Hendrick

Duyst, named Dirck Duyst, was the great-grandfather of Pieter Claesz.'s

grandmother Sara Mennincx. In this case, I would guess that the religious gap separating the families of Pieter van Ruijven and Catharina

Bolnes - he was Calvinist, she was Roman Catholic with Jesuit sympathies - was more important than their distant kinship.

4Naumann, ii, 25-27, and Jan van Gelder and Ingrid Jost, Jan de Bischop

and His Icones and Paradigmata; Classical Antiquities and Italian Drawings for Artistic Instruction in Seventeenth Century Holland, Dornspijk,

1985, 42.

5 Delft Gemeente Archief - henceforth Delft G.A. - Old Church, Baptism files. Pieter Spierincx's mother, Oncommera Mennincx, was a witness

at the baptism of Pieter Claesz.'s sister Sara on 27 April 1631. The only

female witness, she was most probably Sara's godmother.

VERMEER'S PATRONS

69

cousin at least on this occasion. Pieter Spierincx died in

1652, one year before Vermeerentered the Guild of St. Luke

in Delft.

Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, born in December 1624,6 was

eight years older than Vermeer. He is not known to have

had any trade or profession. Like his father before him, his

only municipal function was to be a master of the Camer

van Charitate (from 1668 to 1674).7 He and his wife, Maria

Simonsdr. de Knuijt, whom he married in August 1653,8

presumably inherited most of their wealth, which they later

augmented by judicious investments.

It was perhaps through Pieter van Ruijven's brother, the

Notary Johan or Jan van Ruijven, before whom Vermeer

and Catharina Bolnes appeared on the day of their betrothal,9 that the artist met his future patron. The first certain contact between Pieter van Ruijven and Vermeer occurred in 1657 when Pieter lent Johannes and Catharina

200 guilders. 10This loan may have been an advance toward

the purchase of one or more paintings. The sale of the Girl

Asleep at a Table generally dated 1657-58, of The Officer

and the Laughing Girl of 1658-59, of The Little Street of

1658-60, and of the Women Reading a Letter in Dresden of

1659-60, all four of which turned up in the auction of Dissius' paintings in 1696 and had almost certainly once belonged to Pieter van Ruijven, may have helped to repay

the loan of 1657.11

On 19 October 1665, Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven and

Maria de Knuijt passed their last will and testament before

Notary Nicholaes Paets in Leyden. The choice of a Leyden

notary may have been dictated by the need for discretion:

the testators stipulated that they did not wish certain members of the family, including the Notary Johan van Ruijven,

to learn the disposition of their estate. It is probably significant, in view of the Van Ruijven family's Remonstrant

proclivities, that Notary Paets was one of the most eminent

members of the Remonstrant community in Leyden.12

Three separate documents were drafted, approved, and

signed before Notary Paets: a joint testament of the couple,

the appointment of the guardians to any child or children

left after their death, and a separate testament of Maria de

Knuijt, which would only become valid if she survived her

6 Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, son of Niclaes Pietersz. van Ruijven and

Maria Graswinckel, was baptized in the Old Church on 10 December

1624. The witnesses were Hermanus van der Ceel (the notary of Vermeer's

father's family from 1620 to 1626), Baertge Adams, and Adriana Munnincx. (Delft G.A., Old Church, Baptism files.) Adriana Munnincx was

probably a sister of Pieter Spierincx's mother, Oncommera.

7 Nederlandsche leeuw, xxIx, 1911, col. 198. The family's brewery business seems to have failed some time after Niclaes Pietersz.'s death (ca.

1650). (Delft G.A., records of Notary W. Assendelft no. 1867, 12 August

1658.)

dates in these and other sources are based on the artist's stylistic evolution,

from which their probable sequencing is inferred. The assumption implicit

in these dates is that the evolution of Vermeer's style from 1656 to 1668

and from 1668 to 1675 (the only dates for which we have evidence) was

steady through time.

8Delft G.A.,

Betrothal and Marriage files.

9 Blankert, doc. no. 10 of 5 April 1653, 146.

10Ibid., doc. no. 15 of 30 November 1657, 146. On Vermeer's financial

circumstances in the period 1653-57, see J.M. Montias, "Vermeerand His

Milieu, Conclusion of an Archival Study," Oud-Holland, xciv, 1980, 4647.

11Blankert, doc. no. 62 of 16 May 1696, 153-54. The dates I have assigned

to Vermeer's paintings are those given in Blankert and Wheelock. The

husband.13

In the joint testament, Pieter Claesz. and Maria, living

on the east side of the Oude Delft canal in Delft, named

each other universal legatees. The survivor must bring up

any child or children left after the decease of one or the

other of the testators. (This clause probably referred to

Magdalena van Ruijven, the only child of the couple left

alive after their death, who was exactly ten years old at

this time.)14 This same survivor must also give 6,000 guilders in one sum to this child or children. In the second

document, they named Gerrit van der Wel, notary in Delft,

as guardian of their surviving child or children. In case of

his death or absence, the secretary of the Orphan Chamber

in Delft was to be appointed in his place, with the authority

to name a substitute to replace him. They specifically excluded Jan Claesz. van Ruijven, notary in Delft, or any of

the testator's nephews or cousins from the guardianship and from any knowledge regarding the succession. The testator recalled that his maternal grandmother Sara Mennincx, widow of Cornelis Jansz. Graswinckel, had left her

property to him and to his descendants in fidei commissary

(in perpetual trust) but that, in defiance of her testament,

his father Claes Pietersz. van Ruijven had appropriated

these assets to himself and sold them. Nevertheless, he did

not wish to bring suit over this alienation to reappropriate

the goods to which he and his descendants were entitled.

After the death of the survivor of the two testators, the

testament read, the guardians of the children should put

away and preserve the linen, gold, silver, and other similar

wares in the estate to turn it over to them after they had

reached legal age or gotten married. The testators further

stipulated that the Masters of the Orphan Chamber and

the guardians should dispose of the paintings ("de schilder

konst"), which would be found in the house of the deceased, according to the dispositions specified in a certain

book marked with the letter A, on which would be written

"Disposition of my 'Schilderkonst'and other matters."They

wished this book to be considered an integral part of the

testament.

12 Pieter van Ruijven was no stranger to Leyden. About the time he drew

up his testament, he was involved locally in a suit over the purchase of

shares in the United East India Company that had belonged to the wealthy

estate of Johannes Spiljeurs (Delft G.A., records of Notary W. van Assendelft, May 1663, act no. 3316, and Leyden G.A. Rechterlijk Archief

92, fol. 202, cited in a letter from P.J.M. de Baar to the author).

13 Leyden G.A., records of

Notary N. Paets no. 676, 19 October 1665,

acts nos. 97, 98, and 99.

14Magdalena van Ruijven, daughter of Pieter van Ruijven and Maria van

Ruijven (who often used her husband's name instead of her own), was

baptized in the Old Church on 12 October 1655. The witnesses were Jan

van Ruijven (the notary), Maria van Ruijven (the sister of Pieter Claesz.),

and Machtelt de Knuijt (almost certainly the sister of Maria de Knuijt);

Delft G.A., Old Church, Baptism files.

70

THE ART BULLETIN MARCH 1987 VOLUME LXIX NUMBER 1

In the testament of Maria de Knuijt, which would only

acquire validity in case of her husband's predecease, the

testatrix approved the two previous acts and named as her

universal heir her child or children and their descendants.

If she left no child or children after her husband's death,

then her property should be divided into three equal parts:

one third she bequeathed to the Orphan Chamber of Delft

to aid the poor, another third to the Camer van Charitate

also for the support of the poor, and the last third to the

"Preachers of the True Reformed Religion in Delft" who

were to distribute them in turn to "expelled preachers having studied the Holy Theology."'5Sara and Maria van Ruijven, sisters of her husband, Pieter van Ruijven, would be

permitted to enjoy the usufruct of all her property their life

long and to chose among her household goods any that

they might wish to have, with the exception of the best

"schilderkonst."Finally, she made various bequests "in the

aforesaid case," which I interpret to mean in case she were

to die childless. If this interpretation is correct, the bequests

that follow were to be made before the rest of the estate

was divided into three equal parts.

Maria de Knuijt left 6,000 guilders to the children of her

late brother Vincent de Knuijt and after their death to their

descendants; 6,000 guilders to Floris Visscher, her husband's nephew or cousin, merchant in Amsterdam, and,

after his death, to his descendants; 1,000 guilders to the

surgeon Johannes Dircxz. de Geus, and, after his death, to

his descendants; and 500 guilders to Johannes Vermeer,

painter. Following the bequest to Vermeer, the following

words were crossed out: "In case of his [Vermeer's] predecease, neither to his children nor to his descendants."

They were replaced by the marginal addition: "However,

in case of his predecease the above aforesaid bequest will

be annulled" ("sall 't voors. legaet te niet zijn"). The different wording had the effect of excluding Catharina Bolnes

from the succession. Of all these conditional bequests, the

one to Vermeer was then the only one that was clearly reserved for him and him alone. The reason for this discrimination was perhaps that Maria de Knuijt, whose sympathies with the Reformed Church were clearly expressed in

the disposition of the bulk of her estate if she died childless,

did not wish any of her money to benefit Jesuits or Jesuit

sympathizers. While I do not know the precise family relationship between the testatrix and the surgeon De Geus,

I infer that such a relationship existed from the burial of

two of his children in the family plot of Pieter Claesz. van

Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt.16Johannes Vermeer was then

the only individual who did not belong to Pieter van

Ruijven's or to Maria de Knuijt's family who was singled

out for a special bequest. This is a rare, perhaps unique,

instance of a seventeenth-century Dutch patron's testamentary bequest to an artist. This token of affection together with the repeated mentions of the "schilderkonst"

they owned suggest that Pieter van Ruijven and Maria de

Knuijt had bought a number of paintings by Vermeer by

1665 when this testament was made.

I have already speculated that several paintings in the

Dissius sale of 1696 probably entered the Van Ruijven collection shortly after they were painted in the late 1650's.

From 1660 to 1665 other pictures that eventually descended

to Jacob Dissius may have been acquired by the Van

Ruijvens, including The Milkmaid of about 1660, The Concert in the Isabella Gardner Museum (about 1664-65), and

the very large View of Delft generally dated 1663. It is also

probable that three paintings by Emanuel de Witte and four

paintings by Simon de Vlieger, which also turned up in the

Dissius inventory,17 belonged to the best "schilderkonst"

consigned in the little book marked A (which has unfortunately disappeared).

Van Ruijven and his wife, passionate collectors though

they may have been, were wealthy enough to buy paintings

without denting their fortune. On 11 April 1669, Willem,

Baron of Renesse (or Renaisse), put up for sale at auction

the domain of Spalant, consisting of twenty-and-a-half

morgen of land situated near the village of Ketel, not far

from Schiedam. With the domain that occupied more than

half the Seigneury of Spalant came the title of Lord of Spalant. The property was bought by Pieter Claesz. for 16,000

guilders.18 When he witnessed the last will and testament

of the framemaker Anthony van der Wiel and of his wife

Gertruy Vermeer (the artist's sister, 1620-70) in their home

ten months later, he proudly called himself Lord of Spalant.19 He may have been there simply to buy frames, but

he is more likely to have attended the act to promote or

protect Vermeer's interests. (In her testament Gertruy left

400 guilders to her "heirs ab intestato," who probably consisted exclusively of Vermeer, in case she predeceased her

husband - as she actually did.)

The only known testamentary provisions made by Pieter

van Ruijven and his wife after the will they had passed

before Notary Paets in Leyden was a codicil dated June

1674.20 By this time Van Ruijven was said to reside in The

Hague but to be lodged on the Voorstraet in Delft (where

he is known to have owned a house).21 After confirming

the validity of the Leyden will of 1665, he noted that, since

that time, he had bought the domain of Spalant and registered the feud in his name. He now bequeathed the Seigneury to his daughter after his death, subject to his wife's

15These were

Rpformed preachers who had been expelled from Habsburg

Bohemia, France, and other Catholic territories.

16Beresteyn, 148.

19Delft G.A., records of Notary G. van Assendelft no. 2128, fol. 31415v, 11 February 1670.

20Delft G.A., records of Notary A. van de Velde of 30 June 1674, fol.

377.

21 Delft

G.A., Huizen protocol, Pt. III, no. 3439/491A, fol. 767. The other

house, situated on the Oude Delft, is recorded in pt. III, no. 4128/1180A,

fol. 923.

17 See the discussion below.

18Delft G.A., records of Notary W. van Assendelft of 11 April 1669, act

no. 3663.

VERMEER'S PATRONS

enjoyment of the usufruct during her life. The daughter in

question was almost certainly Magdalena.22

Jacob Dissius

Pieter van Ruijven was buried on 7 August 1674,23 seventeen months before the artist whom he had protected,

and most probably befriended, for the greater part of his

career. Pieter Claesz.'s daughter Magdalena married Jacob

Abrahamsz. Dissius on 14 April 1680.24 The marriage contract has not been preserved. This is too bad because it may

have been the key to the settlement of Magdalena's estate

after her death, which will be discussed below. The conjecture, which I owe to S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, is that

Jacob's father, Abraham Dissius, who owned the printing

press "The Golden ABC" on the Market Square, may have

given him the press as a sort of dowry in order to redress

the inequality of wealth between his son and his bride-tobe. Magdalena had already inherited considerable assets,

including the domain of Spalant, from her father, subject

to her mother's right of usufruct. Jacob, who was twentyseven years old at the time of his marriage,25had no means

of his own; he had registered in the Guild of St. Luke as a

bookbinder in 1676. He did not register in the guild as a

bookseller - thus presumably as the owner of a bookselling establishment - until six months after his marriage,

in November 1680.26 Even then he had so little money that,

when his wife died two years later, he had to borrow from

his father to pay her ordinary death debts (costs of burial,

mourning clothes, and so forth).27 Jacob's main asset was

his distinguished Protestant background: he was the grandson of Minister Jacobus Dissius, pastor in Het Wout, near

Delft, and of Maria von Starrenberg.28

On December 3 of the same year, 1680, the young couple

passed their testament before a notary in Delft.29 They

named each other universal heirs, subject to the usual provision that the survivor must bring up their child or children in an appropriate manner. If the testator remarried

after his wife's death, he obligated himself to pay her mother

(Maria de Knuijt), if she was still alive, 500 guilders, and

if she was already dead, her relatives and collateral descendants 200 guilders. On the other hand, if they both died

without children and without having remarried while their

parents on either side were still alive, then they willed that

22 A

daughter of Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt named

Maria was baptized on 22 July 1657 in the Old Church. A son named

Simon was baptized in the same church on 27 January 1662 (Delft G.A.,

Old Church, Baptism files). Both these children must have died early since

no other heir beside Magdalena was ever mentioned.

23 Beresteyn, 418.

24Delft G.A., Betrothal and Marriage files.

25 Jacob Dissius was

baptized in the New Church on 23 November 1653.

His grandfather Jacobus Dissius and his aunt Jannetje Dissius were witnesses (Delft G.A., New Church, Baptism files).

26The registrations in the guild of Jacob Dissius, his father Abraham, and

his uncle Jacob Jacobsz. are cited in F.D.O. Obreen, Archief voor Nederlandsche kunstgeschiedenis, Rotterdam, 1877, I, 52, 58, 83, 86.

27 Delft G.A., records of Notary P. de Bries no. 2325, act no. 31,

early

71

their estate, including the domain of Spalant, be divided

into two equal parts, the parents on each side receiving

half. In the case of the domain of Spalant, however, the

division was not to be effected until the death of Maria de

Knuijt (who was entitled to the domain's usufruct). Magdalena van Ruijven, then referring explicitly to the twentyand-a-half morgen in Spalant with which she had been

vested in December 1680 and of which she was therefore

entitled to dispose, subject to her mother's usufruct, willed

that after her death the domain should be assigned to her

"beloved husband Jacob Abrahamsz. Dissius." To give effect to this provision, she wished that, at the first opportunity, his name should be inscribed in the register of feuds

in place of her name so that he should enjoy the fruits and

rents of the domain immediately after her mother's death.

No special provision was made for the paintings or for any

other of the couple's household goods.

Three months later, on 26 February1681, Maria de Knuijt

was buried next to her husband in the family plot in the

Old Church.30 Her daughter Magdalena did not survive her

long. She was only twenty-seven years old when she died

on 16 June 1682.31She seems to have left no surviving child.

Jacob Dissius was the apparent heir of the entire Van

Ruijven estate, including the paintings.

Nine months after the death of Magdalena Pieters van

Ruijven, an inventory was prepared of the property left to

her husband, Jacob Dissius, in which twenty works by Vermeer were recorded (one more than Bredius reported).32 I

presume that the bulk of the estate, including the household

goods and paintings, had been inherited by Magdalena from

her father, Pieter Claesz..

The inventory drawn up almost a year after the death

of Magdalena van Ruijven listed all the goods, movable

and unmovable, accruing to Jacob Dissius both in his own

right and as inherited through the death of his wife. Among

the principal assets were the domain of Spalant, numerous

interest-bearing obligations in the name of Maria de Knuijt

bought between 1663 and 1674, and the rental money 175 guilders per year - on the house in the Voorstraet, all

this of course devolved from Magdalena. The only asset

that was explicitly said to belong to Jacob Dissius in his

own right was a life annuity yielding 100 guilders per year.

The principal liability of the estate was the 400 guilders that

April 1683, partly published in Bredius (as in n. 2).

28 Jacob's uncle Karel

Dissius, who dealt in gloves and other apparel, was

married to Machtelt de Langue, the niece of Willem Reyersz. de Langue,

the notary, collector, and friend of the Vermeer family. These and other

kinship relations in the Dissius family can be traced from a document

relating to the sale of a house belonging to the De Langue family in the

records of Notary T. van Hasselt no. 2151, 9 August 1660 (Delft G.A.).

29 Delft G.A., records of Notary D. van der Hoeve no. 2359 of 20 June

1682, act no. 26. This act contains the testament of 3 December 1680,

which was opened and read on 20 June 1682.

Beresteyn, 148.

The Dissius inventory of April 1683 (see n. 27 above), cites the exact

date of Magdalena's death.

32 Doc. cited in n. 27 above.

30

31

72

THE ART BULLETIN MARCH 1987 VOLUME LXIX NUMBER 1

Dissius had borrowed from his father to pay various expenses connected with Magdalena's death.

After the unmovable assets, the notary's clerk listed the

movable goods in each room of the Dissius house. In the

front hall, he noted eight paintings by Vermeer, together

with three more paintings by Vermeer in boxes, all of unspecified subjects. The front hall also contained a seascape

by Porcellis and a landscape. In the back room there were

four paintings by Vermeer, two paintings of churches, two

"tronien"(or "faces"),two night scenes, one landscape, and

"one [painting] with houses." This room also contained a

chest with a viola da gamba, a hand-held viol, two flutes,

and music books. In the kitchen, which was apparently also

a bedroom, there was a painting by Vermeer(the one missed

by Bredius), two "tronien," a night scene, two landscapes,

a "littlechurch"and a "painter."In the basement room there

were two paintings by Vermeer plus a landscape and a

church. The list closed with two paintings by Vermeer and

two small landscapes whose precise location in the house

was not specified.

Two years later, in April 1683, the estate was divided

between Jacob and his father, Abraham Dissius.33The introduction to this notarial document setting forth the terms

of the division stated that Jacob Abrahamsz. Dissius and

Magdalena Pieters van Ruijven had owned the goods in the

estate in common and that Magdalena had left as her heir

her father-in-law Abraham Jacobsz. Dissius in conformity with her testament of December 3 and the act of superscription of 10 December 1680. Actually, the testament,

confirmed by the act of superscription, had named the survivor of the two testators as universal heir. Magdalena's

father-in-law Abraham Dissius was only to inherit the bulk

of the estate in case both testators died without children,

neither having remarried, and Magdalena's mother was also

deceased. Maria de Knuijt had indeed died, and Magdalena

had left no children, but, since Jacob was very much alive,

it is not immediately obvious why he had to give up half

of the estate to his father. I have already cited S. A. C.

Dudok van Heel's suggestion that the marriage contract

may have contained a clause that allowed Abraham to share

in his daughter-in-law's estate. In any event, the succession

had not proceeded without controversy. It was only after

Magdalena's heirs ab intestato, who must have included

her husband, her father's sisters Sara and Maria, and her

mother's brother Vincent de Knuijt, had appeared with

Abraham Dissius before the commissioners of the High

Court of Holland on 18 July 1684 and again on 16 February

1685 that the decision was handed down that prescribed

the division of the estate half and half between Abraham

Dissius and his son Jacob. It was probably also the com-

missioners who had stipulated precisely how the division

would have to be made.

All the movable goods in the estate, including the printing press, were divided into two lots. The household goods

in the estate, starting in the inventory of 1683 with "a lot

of firewood" and ending with "two black hats," would accrue to lot A, with the exception of fourteen paintings that

would be transferred to lot B. Lot B consisted chiefly of

the printing establishment and the equipment going with

it. The paintings that were to be transferred from lot A to

lot B were: three landscapes by S. de Vlieger, three temples

or churches by Emanuel de Witte, two portraits or "tronien," and six paintings by Johannes Vermeer to be chosen

from lot A by the individual who would receive lot B.

Of the four paintings of churches in the inventory of

1683, the 1685 disposition of the estate assigned three by

Emanuel de Witte to lot B. At least one of the three, and

probably two, adorned the back room with the four paintings by Vermeer that were said to hang there.34Of the seven

landscapes in the inventory, three by Simon de Vlieger had

similarly been shifted to lot B.

When the two principal heirs, father and son, chose

among the lots by chance, lot A fell to Jacob and lot B to

his father Abraham.

Nine years later, on 12 March 1694, Abraham Dissius

was buried in the New Church.35His property, including

the fourteen paintings that had been transferred from lot

A to lot B, were presumably inherited by his son Jacob,

who seems to have been his universal heir.36

Jacob Dissius himself died in October 1695. The widower

on the Market Square in "The Golden ABC" was transported by coach, with eighteen pallbearers, to his family's

resting place in Het Wout.37Six months later an advertisement appeared in Amsterdam announcing an auction containing twenty-one paintings by Vermeer "extraordinarily

vigorously and delightfully painted."38This number was

one more than that listed in the inventory of 1683. Clearly,

Jacob must have bought back, or inherited, from his father

the six paintings by Vermeer that had fallen to Abraham's

lot. How did the Dissius collection expand from twenty to

twenty-one Vermeers between 1685 and 1695? Perhaps the

twenty-first was there all along. It is possible that the

"painting with houses" in the inventory of 1683 was identical with The Little Street, now in the Rijksmuseum, in

which case it would have been omitted by error from the

list of paintings attributed to Vermeer.

The top prices for the twenty-one paintings by Vermeer

sold in Amsterdam on 16 May 1696 were 155 guilders for

the "Young Lady Weighing Gold" (The Woman with the

Balance), 175 guilders for the "Maid Pouring Out Milk"

33Delft G.A., records of Notary P. de Bries no. 2327, between 14 and 20

April 1685.

34The clerk had initially specified that one of the church paintings in the

backroom portrayed a burial. This is likely to have been the "Grave of

the Old Prince in Delft" by De Witte in the Dissius sale of 1696 (doc. cited

in n. 39 below).

3s Delft G.A., New Church, Burial files.

36Jacob seems to have been the only one of six children fathered by Abraham Dissius who survived infancy. It is worth noting that Jacob Dissius,

in his testament of 7 February 1684, made his father his universal heir

(Delft G.A., records of Notary P. de Bries, no. 2326, act no. 15).

37Blankert, doc. no. 62 of 14 October 1695, 154.

38 Ibid.

VERMEER'S PATRONS

(The Milkmaid) and 200 guilders for "The City of Delft in

Perspective" (The View of Delft).39All three survive to this

day. Only two relatively expensive paintings have disappeared: one "In which a gentleman is washing his hands in

a see-through room, with sculptures," and "A gentleman

and a young lady making music," which sold for 95 and

81 guilders respectively. The lowest prices were for "tronien," including two for 17 guilders each. The small but

accomplished Lace Maker only brought 28 guilders.

It may be noted in passing that only one of the paintings

by Vermeer in the Amsterdam sale (the first listed in the

catalogue) was in a case or box. This was the "YoungLady

'Weighing Gold," more properly called Woman with a Balance, in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. It must

have been one of the three paintings by Vermeer in boxes

in the front hall of the Dissius house.

Not all paintings by Vermeer owned by Dissius had been

acquired by Pieter van Ruijven. The Woman with a Pearl

Necklace of Berlin-Dahlem, which is very likely to have

been listed in Vermeer's death inventory of 1676 as a

"Woman with a necklace,'"40 was probably bought from his

widow after the artist's death either by Magdalena van

Ruijven or by Jacob Dissius. Since this picture is generally

dated 1664-65, in any case before The Astronomer of 1668,

it follows that, whatever arrangement Pieter van Ruijven

had made with Vermeer, it did not call for the immediate

transfer of all newly completed works.

Some of the paintings by Vermeer sold in 1696 may have

entered the collection of Van Ruijven between the latter's

testament of 1665 and his death, including the Young Lady

Writing a Letter in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Lace Maker in the Louvre, and either the Lady

Standing at the Virginals or the Lady Sitting at the Virginals, both in the National Gallery, London, all of which are

generally dated in the 1670's. Van Ruijven may also have

acquired one or more of the Vermeer "tronien" in the sale

of 1696 during the four or five years preceding the artist's

death. Catharina Bolnes may have been exaggerating when

she claimed that her husband had sold "very little or hardly

anything at all" since 1672.41

The catalogue of the sale of 16 May 1696 opened with

twelve paintings by Vermeer. They were followed by three

paintings by Emanuel de Witte: "The Old Church in Amsterdam," "The Tomb of the Old Prince," and "another

church." These were almost certainly among the fourteen

paintings transferred from lot A to lot B in the Dissius inventory. None of the next fifteen pictures listed by various

Dutch and Italian painters would seem to be identical with

paintings described in the inventory of 1683. Then came

nine lots by Vermeer, starting with "The city of Delft in

perspective." These were followed by "a large landscape"

by Simon de Vlieger and three other landscapes by the same

artist. These are all likely to have belonged to Dissius. The

39The complete list of paintings sold on 16 May 1696 referred to in the

text is given in G. Hoet, Catalogus of Naamlyst van schilderyen, met der

selven pryzen, The Hague, 1752, I, 34-36.

40

Blankert, doc. no. 40 of 29 February 1676, 150-51.

73

next painting listed after the four De Vliegers was a "tronie"

by Rembrandt, which only sold for seven guilders, five

stuivers. It may have been one of the two "tronien" transferred from lot A to lot B in 1685. None of the paintings

listed after the Rembrandt "tronie" appears to have belonged to Dissius in 1683.

The twenty-one Vermeers in the sale brought a total of

1,503 guilders, ten stuivers; the three by Emanuel de Witte,

160 guilders; and the four landscapes by De Vlieger, 125

guilders, fifteen stuivers. The grand total came to 1,796

guilders, ten stuivers (including the Rembrandt "tronie"),

a very respectable sum, even by Amsterdam standards.

Clearly, though, not all the paintings recorded in the Dissius inventory of 1683 were sold in 1696. There was nothing

in the catalogue resembling the Porcellis seascape, the three

night scenes, and the "painter."Moreover, there were only

three of the four churches in the inventory, four of the seven

landscapes, and at most one of the four "tronien." (It is

possible but unlikely that some of the landscapes appeared

elsewhere in the list of paintings sold.) Perhaps only the

best "schilderkonst"noted in the book marked A in the Van

Ruijven testament of 1665 plus the Vermeers acquired after

that time were thought good enough to appear in the Amsterdam auction. The rest may have gone directly to the

collateral heirs of Jacob Dissius (his first cousins on his father's side).

Other Collectors

Beside the dealer Johannes Renialme, the sculptor Johannes Larson, and the innkeeper Cornelis de Helt, who

had each bought an inexpensive picture by Vermeer early

in the artist's career, we know the names of three of his

clients during his mature period: Diego Duarte, Herman

van Swoll, and Hendrick van Buyten, only the last of whom

is known to have been in direct contact with Vermeer.

The rich Antwerp jeweler and banker Diego Duarte

owned "a little piece with a lady playing the clavecin with

accessories by Vermeer," estimated at 150 guilders in July

1682.42 This may have been either The Lady Standing or

The Lady Sitting at the Virginals. Whichever it was, the

other was in the Van Ruijven-Dissius collection.

In 1699 when Herman van Swoll's collection was sold in

Amsterdam, "A seated woman with several [symbolical or

allegorical] meanings representing the New Testament" by

Vermeer of Delft fetched 400 guilders.43This painting was

probably identical with The Allegory of Faith in the Metropolitan Museum. Since there is no evident reason why

the Jesuit Station of the Cross in Delft should have sold a

painting at this time, I suspect that the Van Swoll picture

had been originally painted for a private patron rather than

for the Jesuits themselves. The very high price the painting

brought shows that Vermeer, when he painted in the flat,

classical mode that was in vogue at the time, could produce

41 Ibid., doc. no. 42 of 30 April 1676, 151.

42 Ibid., doc. no. 60 of 12

July 1682, 153.

doc.

no.

63

of

22

April 1699, 154.

43 Ibid.,

74

THE ART BULLETIN MARCH 1987 VOLUME LXIX NUMBER 1

a painting that was nearly as valuable as any sold by the

most fashionable painters of the period.

Herman Stoffelsz. van Swoll, from whose estate the Allegory was sold, was born in Amsterdam in 1632 and died

there in 1698. The son of a Protestant baker, he made a

fortune as a controller ("suppoost") of the Amsterdam Wisselbank and as postmaster of the Hamburger Comptoir in

Amsterdam. He had a house built on the Amsterdam

Herengracht in 1668 where he lived until his death. Nicolaes Berchem, and probably Gerard de Lairesse, painted

decorations with mythological and allegorical figures in the

house. His collection contained many Italian paintings

along with the most distinguished representatives of "modern" Dutch art.44These, however, were not necessarily all

originals. It is known that he employed Nicolaes Verkolje

(born in Delft in 1673, died in Amsterdam in 1746) to make

copies after originals, for which he paid twelve guilders per

copy.45

Our last collector of Vermeer's works is the baker Hendrick van Buyten, who is most probably identical with the

"boulanger"met by the French traveler Balthazar de Monconys in August 1663, on which occasion the baker showed

him a one-figure painting by Vermeer for which he claimed

that 600 livres - presumably equivalent to Dutch guilders

- had been paid.46

Van Buyten, in contrast to Pieter van Ruijven, was of

fairly humble origin. His father, Adriaen Hendricksz. van

Buijten, was a shoemaker. After Adriaen Hendricksz. died

in 1650, his widow sold his household effects for only 796

guilders.47Hendrick himself must have done well as a baker,

but it was the inheritance he received from his relative

Aryen Maertensz. van Rossem in 1669, from which he obtained nearly 4,000 guilders and a house in the Oosteynde,48

that was probably the principal source of his new wealth,

which he later built up by lending money at interest. It is

significant that, when Monconys inquired about Vermeer's

paintings, he was steered to Van Buyten, who apparently

had only one picture by him, rather than to Pieter van

Ruijven, who presumably had at least a half dozen of them

by this time: the baker, being a tradesman, was more likely

to sell than the patrician. (The exorbitant price he claimed

he had paid for his one-figure Vermeer may have been inflated for the sake of bargaining.)

After Hendrick van Buyten died in July 1701, leaving a

widow but no children, his estate was administered by the

44On Herman van Swoll, see Willem van de Watering, "The Later Allegorical Paintings of Niclaas Berchem," in Exhibition of Old Master

Paintings, Leger Galleries, London, 1981. I am indebted to JenniferKilian

for this reference.

45 S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, "Hondervijftig advertenties van kunstverkopingen uit veertig jaargangen van de Amsterdamsche Courant," Jaarboek Amstelodamum, LVII,1980, 150. In the advertisement for the sale

of 1699 in the Amsterdamsche Courant, it was said the collection had

been formed "with great trouble over a period of many years." "The Allegory of the New Testament"was singled out as "an artful piece by Vermeer of Delft" (ibid., 160).

46 Blankert, 147.

Orphan Chamber of Delft. The contents of his "boedel" in

the Delft Orphan Chamber archives are distributed among

ten bundles enclosed in five large boxes.49Some of the papers date as recently as 1849 when printed notices were sent

out to a long list of heirs notifying them of the small

amounts of interest on restricted capital funds that they still

had coming to them from their "greatuncle's" inheritance.

The inventory of 1701 listed the movable possessions of

Hendrick van Buyten and his wife Adriana Waelpot. She

was the daughter of the printer Jan Pieters Waelpot and of

Catharina Karelts, and was born the same year as Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes (1631). Van Buyten was born

the same year as Vermeer (1632). After Hendrick had

lost his first wife, named Machtelt van Asson (a baker's

daughter), he had married Adriana in November 1683.50

Adriana's father owned an important printing press in Delft

comparable to that of Abraham Dissius. From the presence

of the Institution by Jean Calvin in Van Buyten's inventory,

we may safely conclude that he belonged to the established

Reformed religion. Thus both Jacob Dissius and Van Buyten were Calvinists and either owned or were connected

with important printing establishments.

The marriage contract between Hendrick and Adriana

of 6 December 1683 had specified that the properties

brought to the marriage by husband and wife were to remain separate ("geen gemeenschap"). The paintings listed

below were all part of Van Buyten's possessions at the time

of his second marriage. He had apparently acquired no

paintings between 1683 and 1701. We can be virtually certain that he owned no paintings that had belonged to Jacob

Dissius in April 1683 and which were still in the Dissius

household two years later when the estate was divided.

The total Van Buyten estate was valued at 24,829 guilders, one of the largest I have seen in my study of Delft

inventories.

The first work of art listed in the inventory of Van Buyten's household goods was "a large painting by Vermeer"

("een groot stuck schilderie van Vermeer")in the front hall.

(The inventories of Cornelis van Helt in 166151and of Jacob

Dissius in 1683, too, began with paintings by Vermeer in

the "voorhuijs.") Also in the front hall was a painting by

Bramer, a society piece by (Anthony) Palamedes, another

little painting by Palamedes, and one by (Nicholas?)

Bronckhorst who painted seascapes. There were seventeen

other unattributed paintings in this hall, representing land-

47Delft G.A., Orphan Chamber. Estate papers (boedel) no. 264 of Adriaen Hendricksz. van Houten, shoemaker. The names and ages of the

heirs (Hendrick, Emerentia, and Adriaen) leave no doubt that this "Van

Houten" was Hendrick van Buyten's father. Note, incidentally, that Adriaen Hendricksz. was acquainted with Vermeer's father (J.M. Montias,

"New Documents on Vermeer and His Family," Oud-Holland, xcI, 1977,

276).

48Delft G.A., records of Notary D. Rees, no. 2144 of 1 April 1669.

49 Delft G.A., Orphan Chamber, Estate papers (boedel) no. 265 Ix.

50 Delft G.A., Baptism files, 21 September 1631, and Betrothal and Marriage files. The betrothal took place on 27 November 1683.

51 Delft G.A., Orphan Chamber, Estate papers (boedel) no. 673 I and ii.

VERMEER'S PATRONS

scapes, still-lifes, and genre paintings, one history painting

(Moses), and one of the young Prince Willem adorned with

flowers. A side room next to the front hall contained three

landscapes by (Pieter) Van Asch (next to the bedstead) and

"two little pieces by Vermeer" ("stuckjes van Vermeer")52

plus eleven other paintings, large and small. In a back hall

the notary found seven little paintings ("stuckjes schilderie") and three little paintings on panel ("borretjes").(The

distinction was sometimes made between "schilderien"

painted on canvas and "borts"or "borretjes"on panel.) The

only other items of interest were a few Protestant books

and "two boxes for paintings" in the attic, which are likely

to have been those in which paintings by Vermeer had once

been preserved. (No other artist on the list of attributed

paintings was "fine" enough to have so encased his

paintings.)

It is remarkable that all five of the painters cited in Van

Buyten's inventory - Vermeer, Bramer, Anthony Palamedes, (Nicholas) Bronckhorst, and Pieter van Asch were born in Delft, became masters of the local guild, and

died in Delft. All had registered in the guild before 1653.

Compared to the Van Ruijven-Dissius collection, Van Buyten's appears to have been somewhat provincial and oldfashioned. (Three out of four of the painters in the Dissius

collection at one time registered in the Delft guild, but two

of them -

Simon de Vlieger and Emanuel de Witte -

left

for Amsterdam and continued to be productive there. Porcellis was initially a Haarlem artist but also worked in Amsterdam and Soetermeer.) The Van Buyten collection probably had not changed very much from the 1650's or 1660's

until the baker's marriage in 1683, with the likely exception

of the two paintings he had acquired from Vermeer'swidow

shortly after the artist's death as collateral for a large debt

incurred for bread delivered: the "person playing on a cittern" and the painting "representing two persons one of

whom is sitting writing a letter."'3 The first of these may

be The Guitar Player in Kenwood or, less probably, the

Woman Playing a Lute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

52In another, posterior version of the same

inventory (Delft G.A., records

of W. van Ruijven no. 2295, act no. 114), the only difference in the description of the paintings that I could find was that the two paintings by

Vermeer in the room next to the front hall were called "stucken" rather

than "stuckjes."It is not obvious whether the clerk decided the paintings

were not as small as he had previously made them out to be or whether

he was inattentive in copying the original inventory. The diminutive

"stukxken," incidentally, was applied to "The Lady playing the clavecin"

in the Duarte inventory, which either measured 51.7 x 45.2cm (Lady

Standing at the Virginals) or 51.5 x 45.5cm (Lady Seated at the Virginals).

The Guitar Player in Kenwood (53 x 46.3cm) and the Woman in Blue

Reading a Letter(46.5 x 39cm) were approximately of the same dimensions

and might have been perceived as "stuckjes." (The dimensions are cited

from Blankert, 160, 167, 169, 170.)

s3 Blankert, 149-50.

I owe the suggestion that the large painting in Van Buyten's front hall

was the Frick picture to Otto Naumann. On the size of the Lady With

Her Maidservant, see Blankert, 164. Willem L. van de Watering, in his

catalogue contribution to Blankert, stated that the Lady Writing a Letter

with Her Maid in the Beit Collection had been pledged to Hendrick van

Buyten by Vermeer'swidow (p. 168). The argument supporting this claim

54

75

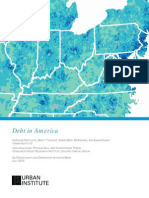

1 Vermeer,Ladywith Her Maidservant.New York,FrickCollection (photo: collection)

The second is probably the Lady with Her Maidservant in

the Frick Collection (Fig. 1). The latter, which measures 92

x 78.7cm, is certainly large enough for the clerk who drafted

the inventory to have perceived it as a "groot stuck schilderie."54The fact that the painting was apparently left unfinished - as the undifferentiated, excessively uniform passages, especially in the main figure, testify55- adds to the

likelihood of this hypothesis, considering that the picture

was still in the artist's studio at the time of his death. If

this was the large painting in the front hall, then the picture

is that the lady in the Beit picture is actually writing, whereas the lady

in the Frick Collection has been interrupted by her maid and has dropped

her pen. In my view, this is only a small inaccuracy on the part of the

notary's clerk. The Frick picture, which is substantially bigger than the

Beit Vermeer (71 x 59cm), is much more likely to have been seen as a

"large painting." The Love Letter in the Rijksmuseum, if this reasoning is

correct, would be the picture in the Dissius Collection sold in 1696 called

"Eenjuffrouw die door een meyd een brief gebracht wordt" (A lady who

is brought a letter by a maid).

Regarding the possibility that the "person playing on a cittern" may

have been confused with a lute player (e.g., the painting by Vermeer in

the Metropolitan Museum), one would have expected the contemporaries

of Vermeer to know the difference between a cittern and a lute. Nevertheless, it should be observed that the Kenwood picture can be traced

back to a public sale in 1794 when it was described as "a woman playing

on a lute" (Blankert, 169). Another version of the Kenwood picture also

exists (now in the Johnson Collection in Philadelphia), which most art

historians have deemed to be a copy after the Kenwood original. The late

hairstyle of the guitar player in the Johnson picture (let alone the weak

execution) would seem to rule it out as a candidate for the painting that

was once in the Van Buyten Collection.

ss Blankert, 55.

76

THE ART BULLETIN MARCH 1987 VOLUME LXIX NUMBER 1

of the "person playing on a cittern" was in the room next

to the front hall. Its companion was perhaps the one-figure

painting that had been shown to Monconys in 1663. In case

this painting was really a "stuckje" as the clerk noted in

1701, Monconys may have had good reason to question

the exorbitant price of 600 livres that Van Buyten said had

been paid for it.

In his testament of 18 May 1701 Van Buyten had left his

wife, Adriana Waelpot, all the household items in the inventory of the goods that he had contributed to the marriage for her lifelong use. However, by an agreement made

with the other heirs before Notary Willem van Ruijven

(which has not been preserved), she consented to have these

goods sold at auction and to collect half the proceeds. The

sale, which took place on 26 April 1702, brought only 674

guilders, six stuivers. Because the schedule ("contracedulle") of the sale has been lost, there is no way to figure

out precisely how much the three paintings by Vermeer

represented of this total.

Conclusions

It may be confidently concluded from the evidence about

Vermeer's clientele gathered in this study that he enjoyed

a strong local reputation during most of his career. He

probably enjoyed some reputation beyond Delft as well,

as the high prices he obtained in the Amsterdam sales of

the Dissius and Swoll collections testify. Beyond reputation, sales, and the artist's financial success, there is another

side to patronage that we have not explored at all so far.

A patron or even an occasional client provides a link to

the social world not normally accessible to an artist of modest background. In Vermeer's case, he did have the wellheeled, patrician relatives of his wife, but those Roman

Catholics apparently did not collect art or at least did not

buy from him. Van Ruijven and Van Buyten, as well perhaps as Van Swoll in Amsterdam, gave the artist entree

into a wider circle of collectors. The pictures that Vermeer

exhibited in their homes were seen by other collectors and

by the artist-friends of these clients. An artist with a reputation like Vermeer could visit painters and collectors in

other cities who were friends of his local protectors. I am

particularly intrigued by the possibility that Vermeermight

have penetrated the Leyden artistic circle thanks to Pieter

Claesz. van Ruijven. We have seen that Van Ruijven was closely related to Pieter Spierincx Silvercroon, the

patron of Gerard Dou. He also knew the Remonstrant notary Nicolaes Paets in Leyden. It was perhaps through Spierincx or Paets that Vermeergained access to Leyden artists

56 Cf. Naumann, I, 99.

s7 In my book Vermeerand His Milieu; A Web of Social History (Princeton University Press, forthcoming), I calculate, on the basis of alternative

assumptions about the rate of disappearance of paintings cited in the 17th

century, that Vermeer painted between forty-five and sixty paintings from

of his generation such as Frans van Mieris. This point is

significant because he was most probably influenced early

in his career by artists of the Leyden school. For his Procuress of 1656, for example, he may have borrowed the

motif of the artist's self-portrait from Frans van Mieris'

Charlatan.56The Leyden connection, in turn, may help to

account for Vermeer's influences in the 1660's on Gabriel

Metsu and Van Mieris himself. Finally, we are entitled to

ask whether Pieter Spierincx might have suggested to Van

Ruijven the idea of acquiring the right to first refusal on

one of Vermeer's paintings per year. This conjecture is in

general accord with what we know of Van Ruijven's collection, the contents of which seem to have been acquired

at a fairly steady rate over the years 1657 to 1673 or 1674.

Van Ruijven's extraordinary patronage also had a negative side. The excessive concentration of Vermeer'spaintings in a single collection, which probably absorbed about

half of his total output after 1656,-7 restricted the possible

scope of his contacts. If he had had other protectors during

his lifetime, preferably in Amsterdam or in Leyden, his

name might not have sunk into near-oblivion in the eighteenth century.58

Professor of Economics at Yale, John Michael Montias has

published articles in Simiolus and Oud-Holland, in addition to his studies in various economic journals. He is author of Artists and Artisans in Delft: A Socio-Economic

Study of the 17th Century (1982) and now is completing a

book entitled Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social

History. [Institution for Social and Policy Studies, Yale

University, P.O. Box 16A Yale Station, New Haven, CT

06520]

Bibliography

Beresteyn, E.A. van, Grafmonumenten en grafzerken in de Oude Kerk te

Delft, Assen, 1938.

Blankert, A., with contributions by R. Ruurs and W. van de Watering,

Vermeer of Delft, Complete Edition of the Paintings, Oxford, 1978.

Naumann, O., Frans van Mieris the Elder, 2 vols., Doornspijk, 1981.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr., Jan Vermeer, New York, 1981.

1656 to the end of his career, with a somewhat greater probability of the

lower estimate.

ss For a balanced view of Vermeer's reputation in the 18th century, see

Blankert, 62-65. He argues that the appreciation for Vermeer's quality

among connoisseurs persisted, even though his paintings were frequently

attributed to other artists with a greater contemporary reputation.

You might also like

- Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social HistoryFrom EverandVermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Architecture of Ekphrasis ContextDocument36 pagesThe Architecture of Ekphrasis ContextRicard MolinsNo ratings yet

- After Iconography and Iconoclasm-WestermannDocument23 pagesAfter Iconography and Iconoclasm-WestermannKalun87100% (2)

- Veltman 2004 Sources - of - Perspective VolDocument340 pagesVeltman 2004 Sources - of - Perspective VoleugenruNo ratings yet

- The Essential Dürer by Grünewald, Matthias Smith, Jeffrey Chipps Pirckheimer, Willibald Frey, Agnes Dürer, Albrecht Silver, LarryDocument309 pagesThe Essential Dürer by Grünewald, Matthias Smith, Jeffrey Chipps Pirckheimer, Willibald Frey, Agnes Dürer, Albrecht Silver, LarryJuan Pablo J100% (2)

- Aesthetic AtheismDocument5 pagesAesthetic AtheismDCSAWNo ratings yet

- March, Linear Perspective in Chinese PaintingDocument29 pagesMarch, Linear Perspective in Chinese PaintingNicola K GreppiNo ratings yet

- Koerner FriedrichDocument46 pagesKoerner FriedrichDaniel GuinnessNo ratings yet

- RIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitDocument34 pagesRIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitRennzo Rojas RupayNo ratings yet

- What I Learned From Karl Popper - An Interview With E. H. Gombrich (By Paul Levinson)Document18 pagesWhat I Learned From Karl Popper - An Interview With E. H. Gombrich (By Paul Levinson)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Giovanni Battista Benedetti On The Mathematics of Linear PerspectiveDocument30 pagesGiovanni Battista Benedetti On The Mathematics of Linear PerspectiveEscápate EscaparateNo ratings yet

- Mel Bochner Why Would Anyone Want To Paint On WallsDocument7 pagesMel Bochner Why Would Anyone Want To Paint On WallsRobert E. HowardNo ratings yet

- THE CLUSTER ACCOUNT OF ART DEFENDED Berys GautDocument16 pagesTHE CLUSTER ACCOUNT OF ART DEFENDED Berys Gautfuckyeah111100% (1)

- Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Vol. 05 ( of 10) Andrea da Fiesole to Lorenzo LottoFrom EverandLives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Vol. 05 ( of 10) Andrea da Fiesole to Lorenzo LottoNo ratings yet

- Francesco Algaroti and Francesco Milizia PDFDocument320 pagesFrancesco Algaroti and Francesco Milizia PDFAliaa Ahmed ShemariNo ratings yet

- Corrada - Geometry - El Lissitzky PDFDocument9 pagesCorrada - Geometry - El Lissitzky PDFAnnie PedretNo ratings yet

- William Kentridge and Carolyn ChristovDocument2 pagesWilliam Kentridge and Carolyn ChristovToni Simó100% (1)

- HH Arnason - International Abstraction BTW The Wars (Ch. 17)Document28 pagesHH Arnason - International Abstraction BTW The Wars (Ch. 17)KraftfeldNo ratings yet

- Since CézanneDocument91 pagesSince CézanneLucreciaRNo ratings yet

- Beuys and Warhol: Recalling Trauma in An Era of Spectacle and SuperficialityDocument11 pagesBeuys and Warhol: Recalling Trauma in An Era of Spectacle and SuperficialityBayley WilsonNo ratings yet

- Anthony Hughes, Erich Ranfft - Sculpture and Its Reproductions (1997)Document219 pagesAnthony Hughes, Erich Ranfft - Sculpture and Its Reproductions (1997)maria100% (1)

- Richard WollheimDocument10 pagesRichard WollheimOnoris MetzNo ratings yet

- Federick Kiesler - CorrealismDocument31 pagesFederick Kiesler - CorrealismTran Hoang ChanNo ratings yet

- Bernard Berenson The Florentine Painters of The RenaissanceDocument182 pagesBernard Berenson The Florentine Painters of The RenaissanceAlejoLoRussoNo ratings yet

- 2009 HendersonDocument31 pages2009 HendersonstijnohlNo ratings yet

- PieroDocument12 pagesPierosotiria_vasiliouNo ratings yet

- MASTERPIECE & MYSTERY: The Enigma of Piero Della Francesca's FlagellationDocument17 pagesMASTERPIECE & MYSTERY: The Enigma of Piero Della Francesca's FlagellationJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Diedrich Diederichsen - Anselm Franke - The Whole Earth - California and The Disappearance of The Outside-Sternberg Press (2013)Document210 pagesDiedrich Diederichsen - Anselm Franke - The Whole Earth - California and The Disappearance of The Outside-Sternberg Press (2013)mihailosu2No ratings yet

- E Corbusier: Charles-Édouard JeanneretDocument22 pagesE Corbusier: Charles-Édouard JeanneretNancy TessNo ratings yet

- T J Clark Painting at Ground LevelDocument44 pagesT J Clark Painting at Ground Levelksammy83No ratings yet

- Woman's Reappearance - Rethinking The Archive in Contemporary Art-Feminist Perspectives PDFDocument28 pagesWoman's Reappearance - Rethinking The Archive in Contemporary Art-Feminist Perspectives PDFTala100% (1)

- Leonardo Da Vinci - Artist, Scientist, Inventor (Art Ebook) PDFDocument637 pagesLeonardo Da Vinci - Artist, Scientist, Inventor (Art Ebook) PDFAna Ventura SanchezNo ratings yet

- Le Feuvre Camila SposatiDocument8 pagesLe Feuvre Camila SposatikatburnerNo ratings yet

- Sublime Simon MorleyDocument9 pagesSublime Simon MorleyDetlefHolzNo ratings yet

- Greenberg, Clement - The Case For Abstract ArtDocument6 pagesGreenberg, Clement - The Case For Abstract Artodradek79No ratings yet

- Branden W. Joseph, White On WhiteDocument33 pagesBranden W. Joseph, White On WhiteJessica O'sNo ratings yet

- Chance ImagesDocument11 pagesChance ImagesRomolo Giovanni CapuanoNo ratings yet

- Clues - Roots of An Evidential ParadigmDocument47 pagesClues - Roots of An Evidential ParadigmDaniela Paz Larraín100% (1)

- Decolonisingarchives PDF Def 02 PDFDocument111 pagesDecolonisingarchives PDF Def 02 PDFANGELICA BEATRIZ CAMERINO PARRANo ratings yet

- Didi Huberman Georges The Surviving Image Aby Warburg and Tylorian AnthropologyDocument11 pagesDidi Huberman Georges The Surviving Image Aby Warburg and Tylorian Anthropologymariquefigueroa80100% (1)

- Useless - Critical Writing in Art & DesignDocument89 pagesUseless - Critical Writing in Art & DesignHizkia Yosie PolimpungNo ratings yet

- Sophie TaeuberDocument59 pagesSophie TaeuberMelissa Moreira TYNo ratings yet

- Edgard Wind PDFDocument23 pagesEdgard Wind PDFMarcelo MarinoNo ratings yet

- Wood PDFDocument24 pagesWood PDFEdgaras GerasimovičiusNo ratings yet

- Horace Vernet and the Thresholds of Nineteenth-Century Visual CultureFrom EverandHorace Vernet and the Thresholds of Nineteenth-Century Visual CultureDaniel HarkettNo ratings yet

- Leonardo Compl 2003 PDFDocument204 pagesLeonardo Compl 2003 PDFeleremitaargento100% (1)

- What Is An Aesthetic Experience?Document11 pagesWhat Is An Aesthetic Experience?geoffhockleyNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetics of AppearingDocument7 pagesThe Aesthetics of AppearingTianhua ZhuNo ratings yet

- Raising The Flag of ModernismDocument30 pagesRaising The Flag of ModernismJohn GreenNo ratings yet

- Branden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFDocument33 pagesBranden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFjpperNo ratings yet

- Beaune Last Judgment & MassDocument16 pagesBeaune Last Judgment & MassJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Constantin Brâncuşi Vorticist: Sculpture, Art Criticism, PoetryDocument24 pagesConstantin Brâncuşi Vorticist: Sculpture, Art Criticism, PoetryDaniel HristescuNo ratings yet

- Natasa Vilic-Pop-Art and Criticism of Reception of VacuityDocument15 pagesNatasa Vilic-Pop-Art and Criticism of Reception of VacuityIvan SijakovicNo ratings yet

- Earth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96From EverandEarth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96No ratings yet

- St. Eleftheratou Stories About Light at PDFDocument28 pagesSt. Eleftheratou Stories About Light at PDFJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Bystander #9 Super Special Sample - Watermark PDFDocument23 pagesBystander #9 Super Special Sample - Watermark PDFJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Bystander #9 Super Special Sample - Watermark PDFDocument23 pagesBystander #9 Super Special Sample - Watermark PDFJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- The Fate of Empires and Search For Survival John GlubbDocument26 pagesThe Fate of Empires and Search For Survival John GlubbmmvvvNo ratings yet

- U.N Agenda 21 ManifestoDocument351 pagesU.N Agenda 21 ManifestoMr Singh100% (6)

- A New Sustainable Financial System To Stop Climate Change CarneyDocument4 pagesA New Sustainable Financial System To Stop Climate Change CarneyJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Newworldorder00battgoog PDFDocument198 pagesNewworldorder00battgoog PDFFrankie HeathNo ratings yet

- Christologies Ancient and ModernDocument266 pagesChristologies Ancient and ModernJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- ST Ambrose - Hexameron, Paradise, Cain & AbelDocument472 pagesST Ambrose - Hexameron, Paradise, Cain & AbelJoe Magil100% (1)

- Wiesbaden 3004 B 10Document7 pagesWiesbaden 3004 B 10Joe MagilNo ratings yet

- Arnolfini Portrait PerspectiveDocument8 pagesArnolfini Portrait PerspectiveJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Hidden Symbolism in Jan Van Eyck's AnnunciationsDocument26 pagesHidden Symbolism in Jan Van Eyck's AnnunciationsJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Van Eyck's Washington Annunciation Narrative Time and Metaphoric TraditionDocument10 pagesVan Eyck's Washington Annunciation Narrative Time and Metaphoric TraditionJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- 12 Books of Hours For 2012Document106 pages12 Books of Hours For 2012Joe Magil100% (2)

- Folklore Spring 1973Document112 pagesFolklore Spring 1973Joe MagilNo ratings yet

- Art of Eternity 3Document30 pagesArt of Eternity 3Joe MagilNo ratings yet

- Debt in AmericaDocument14 pagesDebt in AmericaJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Fruit and Fertility: Fruit Symbolism in Netherlandish Portraiture of The Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturiesDocument20 pagesFruit and Fertility: Fruit Symbolism in Netherlandish Portraiture of The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuriesjmagil6092No ratings yet

- The Art of Ancient EgyptDocument80 pagesThe Art of Ancient EgyptJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Hades: Cornucopiae, Fertility, and Death by Diana BurtonDocument7 pagesHades: Cornucopiae, Fertility, and Death by Diana BurtonJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Surrealism & CommunismDocument9 pagesSurrealism & CommunismJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Beaune Last Judgment & MassDocument16 pagesBeaune Last Judgment & MassJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- The Trinity by St. AugustineDocument568 pagesThe Trinity by St. AugustineJoe Magil83% (6)

- CIA's Aerial Empire Origins - Oct 1984 Vol 8 No 4Document16 pagesCIA's Aerial Empire Origins - Oct 1984 Vol 8 No 4Joe MagilNo ratings yet

- 3rd Century Christians & MusicDocument39 pages3rd Century Christians & MusicJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- English Liturgical ColorsDocument300 pagesEnglish Liturgical ColorsJoe Magil0% (1)

- Watteau - Charmes de La VieDocument25 pagesWatteau - Charmes de La VieJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- ApocatastasisDocument5 pagesApocatastasisJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Black Perspective On Big Stick Diplomacy - Oct 1984 Vol 8 No 4Document19 pagesBlack Perspective On Big Stick Diplomacy - Oct 1984 Vol 8 No 4Joe MagilNo ratings yet

- Themysorepalace 170710180719Document21 pagesThemysorepalace 170710180719DevrathNo ratings yet

- The Pattern of HapkidoDocument5 pagesThe Pattern of HapkidoanthonyspinellijrNo ratings yet

- Year End Top Worldwide Concert ToursDocument1 pageYear End Top Worldwide Concert ToursZachary MillerNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument13 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldSIMONNo ratings yet

- He Could Have Simply Walked AwayDocument6 pagesHe Could Have Simply Walked AwayHae Rim LeeNo ratings yet

- Guidelines: Nutri-Booth Competition: Theme: "Healthy Diet, Gawing Habit For Life."Document4 pagesGuidelines: Nutri-Booth Competition: Theme: "Healthy Diet, Gawing Habit For Life."Roldan CaroNo ratings yet

- Old Burmese WatercoloursDocument99 pagesOld Burmese WatercoloursCamila FragoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Women in Communal Peace Resolution: A Case Study of Aristophanes' LysistrataDocument44 pagesThe Role of Women in Communal Peace Resolution: A Case Study of Aristophanes' LysistrataFaith MoneyNo ratings yet

- REALME FINAL BOQ - MergedDocument5 pagesREALME FINAL BOQ - MergedRM DulawanNo ratings yet

- Presentation Skills-Unity (MBA)Document55 pagesPresentation Skills-Unity (MBA)Arash-najmaei100% (9)

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Literature in English 9695/13Document16 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Literature in English 9695/13NURIA barberoNo ratings yet

- 6 VR 6 FKQCFB 6 ZR 8 L 5 LT 2Document166 pages6 VR 6 FKQCFB 6 ZR 8 L 5 LT 2supreeth samuelNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan Goals and ObjectivesDocument2 pagesUnit Plan Goals and Objectivesapi-315423352No ratings yet

- Heian Shodan Kata BunkaiDocument25 pagesHeian Shodan Kata BunkaiAlexen267100% (1)

- The Artists Guide To IllustrationDocument164 pagesThe Artists Guide To IllustrationCristina Balan94% (33)

- 1018.duck Blanket and AppliqueDocument6 pages1018.duck Blanket and AppliqueBenevi deNo ratings yet

- Noir Character SheetDocument2 pagesNoir Character SheetJoshua Baird100% (1)

- Jacques Delécluse's Twelve Studies For The Drum: A Study Guide and Performance AnalysisDocument169 pagesJacques Delécluse's Twelve Studies For The Drum: A Study Guide and Performance Analysisvictor_sanchez143777050% (2)

- English-PT 1Document24 pagesEnglish-PT 1Jane Nicole Miras SolonNo ratings yet

- Blue Globe Vector College Trifold BrochureDocument2 pagesBlue Globe Vector College Trifold Brochurehaniya khanNo ratings yet

- 실용영어2 Ybm (박준언) 1과 어법선택Document3 pages실용영어2 Ybm (박준언) 1과 어법선택Hyesook Rachel ParkNo ratings yet

- Taiwan's Master Timekeeper (On Hou Hsiao-Hsien)Document3 pagesTaiwan's Master Timekeeper (On Hou Hsiao-Hsien)Sudipto BasuNo ratings yet

- Script Breakdown 7 Petala CintaDocument59 pagesScript Breakdown 7 Petala CintaKASIH ADINDA DAMIA AHMAD SURADINo ratings yet

- 10 клас Natural ClassicDocument2 pages10 клас Natural ClassicМаряна ШукаткоNo ratings yet

- GEC 6 Chapter 1Document17 pagesGEC 6 Chapter 1RoseAnne Joy Robelo CabicoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O Level: Design & Technology 6043/12Document4 pagesCambridge O Level: Design & Technology 6043/12Ozan EffendiNo ratings yet

- White 1010 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDocument46 pagesWhite 1010 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansNo ratings yet

- NO Nama Citra Jumlah Saluran/ Band Spesifikasi SaluranDocument3 pagesNO Nama Citra Jumlah Saluran/ Band Spesifikasi SaluranFebriantaNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan: School of EducationDocument3 pagesDaily Lesson Plan: School of EducationCiela Marie NazarenoNo ratings yet

- Crash Course Theater and Drama 10 Mystery PlaysDocument2 pagesCrash Course Theater and Drama 10 Mystery Playscindy.humphlettNo ratings yet