Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Feeding Difficulties in Infants and Young Children

Uploaded by

Argadia YuniriyadiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Feeding Difficulties in Infants and Young Children

Uploaded by

Argadia YuniriyadiCopyright:

Available Formats

I N T E G R AT I V E M E D I C I N E

Feeding Difficulties in Infants and Young Children:

Tailor Interventions to Match Child Behaviours

Editorial:

Glenn Berall, MD, FRCPC

Chief of Pediatrics, North York General Hospital

Assistant Professor of Paediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

University of Toronto

Toronto, Ontario

Miami Summit, June 2009 Feeding difficulties in infants and young children are highly prevalent and pediatricians

need to pay close attention to parental complaints in order to identify and categorize the chief problem and tailor

interventions accordingly. This report presents an expert categorization of feeding difficulties and appropriate

consequent treatments. Parental education and reassurance is often sufficient to resolve many feeding issues;

however, providing a nutritionally balanced supplement may help correct malnutrition and ease parental anxiety.

Feeding difficulties in infants and young children are among

the most prevalent complaints encountered in the average

pediatric practice today. Estimates of their prevalence vary but

in physically normal children, 50% to 60% of surveyed parents

report feeding difficulties with their young children, while 25%

to 35% meet criteria for specific difficulties such as food refusal

and selective eating. The consequences of an untreated feeding

difficulty can include failure to thrive, nutritional deficiencies,

impaired parent/child interactions and chronic aversion with

socially stigmatizing mealtime behaviour. As well, a feeding

difficulty can be a sign of an underlying organic disorder such

as eosinophilic esophagitis. It is therefore important to identify

the type of feeding difficulty present.

Categorization of Feeding Difficulties

In pediatrics, a variety of terms are used to categorize

different feeding difficulties, with a resulting lack of common

understanding. To that end, an attempt to apply a single

categorical description has been made by a diverse group

of experts and presented at a meeting in Miami, Florida by

Dr. Benny Kerzner, Professor of Pediatrics, The George

Washington University, Washington, DC; Thomas Linscheid,

PhD, Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Ohio

State University School of Medicine, Columbus; pediatric

gastroenterologist Dr. Russell J. Merritt, Childrens Hospital

Los Angeles, California; and Dr. Irene Chatoor, Childrens

National Medical Center and Professor of Psychiatry, George

Washington University.

Patients were placed into one of the following seven

categories, each with differing features and treatments:

1. Infants with poor appetite because of organic causes.

2. Those with poor appetite due to parental misperception.

3. Those with poor appetite who are otherwise vigorous.

4. Poor appetite in an apathetic or withdrawn child.

5. Children who display highly selective food behaviours.

6. Infants with colic that interferes with feeding.

7. Infants or children who fear feeding.

Interventional Strategies

Situating a childs feeding behaviour into one of the proposed

seven categories helps determine interventional strategies.

1. Children may have poor appetite or refuse food because of an

underlying organic cause and it is critical to systematically

exclude organic causes of poor appetite. If an organic cause is

suspected, then the appropriate investigations must be carried

out to determine the diagnosis and guide treatment. Signs that

would make one suspect underlying organic causes include

but are not limited to dysphagia; recurrent chest symptoms

or pathology; failure to thrive; feeding interrupted by pain,

regurgitation or chronic vomiting; diarrhea or blood in stool;

neurodevelopmental anomalies; atopy and eczema; chronic

cardiorespiratory disease; or signs of neglect.

2. For children with poor appetite due to parental misperception,

parents need to be educated about what they can realistically

expect in terms of their childs growth and nutritional needs

for their age. They also need to understand basic feeding

principles and apply them consistently during feedings.

Reassurance is often all that is needed to improve the

situation. If not, and parental anxiety remains high, then a

balanced nutritional supplement may be considered in order

to allay parental fears and reduce the likelihood that they will

use force or coercion to get their child to eat.

3. Children with poor appetite who are otherwise vigorous are

often more interested in playing than in feeding, are alert,

active and inquisitive but rarely show signs of hunger or

interest in feeding, and are felt by some experts to have

infantile anorexia. Typically, this behaviour occurs during

transition from spoon to self-feeding between 6 months and

3 years of age.

As discussed by Drs. Linscheid and Chatoor, treatment

of poor appetite in a child who is fundamentally vigorous

should promote the childs appetite by increasing hunger

and satisfaction from eating. Principles here include no

grazing between meals, only water; three meals a day plus

an afternoon snack; no distractions during feeding; discrete

mealtimes not longer than 30 minutes; and the use of timeout

to discourage disruptive feeding behaviours. If growth is

faltering, practitioners may recommend parents feed the

child high-calorie foods or use a 30 kilocalories-per-ounce

nutritionally balanced supplement, optimally given after the

dinner meal to least impact on appetite.

4. Poor appetite in a child who is withdrawn and depressed

may be a sign of neglect. If practitioners observe no signs

of smiling, babbling or eye contact between the infant and

caregiver during examination, the child could be at risk for

substantial weight loss and malnutrition and may require

inpatient admission to improve the feeding environment.

Consider socioeconomic circumstances, psychoneurosis in

the mother and neurological problems in the child.

5. Children who consistently refuse specific foods because of

taste, texture, smell or appearance, or who become visibly

anxious if asked to eat foods to which they are averse, often

have additional sensory difficulties. They are upset by loud

noises or they dislike the sensation of sand or grass under

their feet. Highly selective food intake or what Dr. Chatoor

calls sensory food aversion goes beyond normal resistance

to the introduction of new foods and, depending on the foods

refused, may result in deficits of some essential dietary

nutrients. In these circumstances, parents should be taught

to tempt the child with food, not foist it upon them. Parents

should themselves consume new foods without offering the

food to the child, although they can try leaving the food

within the childs reach as toddlers are often more willing

to try new foods if they feel in control. Reassuring the

parent can be helpful. Again, the diet may be supplemented

with a nutritionally balanced product to redress the risk of

micronutrient deficiencies.

6. In infants under the age of 3 months, colicdefined as

inconsolable crying not responsive to usual interventions

and with no obvious pathologycan be problematic because

infants may fail to calm down enough to feed successfully.

If the crying disrupts feeding, mothers often try to feed

infants more frequently, fearing the infant is crying because

they are hungry. Strategies to improve infants with colic

include feeding in a quiet room with dim lights and white

noise, giving the infant a warm bath to break the crying

cycle, swaddling the infant to comfort them or possibly using

kangaroo-style skin-to-skin nursing. Mothers with colicky

infants need to get adequate rest and support and fathers need

to get involved in the feeding and caring of the infant. At the

same time, infants may cry because of pain and discomfort

from feeding and practitioners need to differentiate possible

triggers for crying including food sensitivity, constipation or

gastroesophageal reflux.

7. Fear of feeding is rare, but if a child cries at the sight of food

or the bottle or resists feeding by crying, arching or refusing

to open their mouths, they may have what Dr. Chatoor refers

to as post-traumatic feeding disorder, possibly the result of

a frightening feeding experience such as choking. Parental

education is again key here. If a child fears the bottle, parents

can offer a sippy cup or spoon instead. Parents should also try

to feed the child when they are half asleep and relaxed rather

than when wide awake and stressed at the sight of food. Once

they have succeeded, they will begin to realize that they can

feed their child successfully.

Practical Tips

Anthropomorphic measurements clearly help distinguish

infants and children who are failing to thrive because of poor

appetite. It is also important for practitioners to assess parental

anxiety. If parents perceive that their child is not feeding

well, they may feel pressured to resort to coercive feeding

practices which can be detrimental and can exacerbate feeding

disorders. Acknowledgement of parental anxiety and providing

reassurance, information and a plan of action are helpful in this

regard. However, the specific approach taken depends upon the

category of feeding difficulty.

Summary

Feeding difficulties are very common in young children and they

have the potential to compromise nutrition, growth and cognitive

development. Pediatricians therefore need to pay close attention

to parental complaints about feeding difficulties to determine

the category of feeding difficulty and tailor their interventions

accordingly. This particular attempt to categorize feeding difficulties

in infants and children may serve as a guide in this regard.

To view an electronic version of this publication along with related slides if available, please visit www.mednet.ca/2009/ho10-001e.

2009 Health Odyssey International Inc. All rights reserved. Integrative Medicine Report is an independent medical news reporting service providing educational updates

reflecting peer opinion from accredited scientific medical meetings worldwide and/or published peer-reviewed medical literature. Views expressed are those of the participants and

do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher or the sponsor. Distribution of this educational publication is made possible through the support of Abbott Nutrition Canada under

written agreement that ensures independence. Any therapies mentioned in this publication should be used in accordance with the recognized prescribing information in Canada. No

claims or endorsements are made for any products, uses or doses presently under investigation. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or distributed without

written consent of the publisher. Information provided herein is not intended to serve as the sole basis for individual care. Our objective is to facilitate physicians and allied health

care providers understanding of current trends in medicine. Your comments are encouraged.

Health Odyssey International Inc.

132 chemin de lAnse, Vaudreuil, Quebec J7V 8P3

A member of the Medical Education Network Canada group of companies

HO10-001E ML

You might also like

- Pcsmanual Current PDFDocument355 pagesPcsmanual Current PDFArgadia YuniriyadiNo ratings yet

- Analgesic Effect of Breast Milk Versus Sucrose For Analgesia During Heel LanceDocument32 pagesAnalgesic Effect of Breast Milk Versus Sucrose For Analgesia During Heel LanceArgadia YuniriyadiNo ratings yet

- Safety and Efficacy of Vinyl Bags in Prevention of Hypothermia of Preterm Neonates at BirthDocument3 pagesSafety and Efficacy of Vinyl Bags in Prevention of Hypothermia of Preterm Neonates at BirthArgadia YuniriyadiNo ratings yet

- Skin Integrity Guideline - FinalDocument13 pagesSkin Integrity Guideline - FinalArgadia YuniriyadiNo ratings yet

- Histiocytosis: BackgroundDocument26 pagesHistiocytosis: BackgroundArgadia YuniriyadiNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Module 9 Eng Health PDFDocument80 pagesModule 9 Eng Health PDFVivica MorenoNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Infections Daryl Joel Dumdum, M.DDocument5 pagesAcute Respiratory Infections Daryl Joel Dumdum, M.DJoan LuisNo ratings yet

- Compilation of MacromineralsDocument3 pagesCompilation of MacromineralsJustin AncogNo ratings yet

- 04-Nutrition COURSE PLANDocument5 pages04-Nutrition COURSE PLANPNT EXAM 2016No ratings yet

- Haccp: (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point)Document79 pagesHaccp: (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point)Sinta Wulandari100% (1)

- Care CWS Helen Keller Report07Document8 pagesCare CWS Helen Keller Report07Syamsul ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Final Revised Draft Dropout Study Report by Dr. Dawood Shah January 9 2019 (Flag B)Document83 pagesFinal Revised Draft Dropout Study Report by Dr. Dawood Shah January 9 2019 (Flag B)Khawaja SabirNo ratings yet

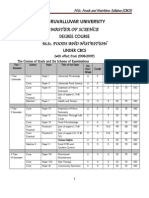

- M.sc. Foods and NutritionDocument43 pagesM.sc. Foods and NutritionGeetha Arivazhagan0% (1)

- The Role of Aquaculture in Improving The Livelihoods of Rural CommunitiesDocument4 pagesThe Role of Aquaculture in Improving The Livelihoods of Rural CommunitiesKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Latest Pediatrics Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - All Medical Questions and AnswersDocument4 pagesLatest Pediatrics Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - All Medical Questions and AnswersAbdul Ghaffar Abdullah90% (10)

- Nutrition Powerpoint Week 2Document20 pagesNutrition Powerpoint Week 2Shaira Kheil TumolvaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Nutritional AssessmentDocument84 pagesLesson 3 Nutritional AssessmentJake ArizapaNo ratings yet

- World HungerDocument5 pagesWorld Hungerveneficus08No ratings yet

- Who Will Feed Us Questions For The Food and Climate CrisesDocument34 pagesWho Will Feed Us Questions For The Food and Climate Criseshtsmith35801No ratings yet

- Nourishing MillionsDocument236 pagesNourishing MillionsAtay UltramanNo ratings yet

- Class 9th: CH 4 Food Security in India EconomicsDocument25 pagesClass 9th: CH 4 Food Security in India EconomicsPankaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report Siga-Indicator 3docxDocument12 pagesNarrative Report Siga-Indicator 3docxMylene Solis Dela Pena100% (7)

- How Do Barangay Nutrition Committees Contribute To Better Nutrition?Document20 pagesHow Do Barangay Nutrition Committees Contribute To Better Nutrition?Angelito CortunaNo ratings yet

- Food Security and Vision 2025Document38 pagesFood Security and Vision 2025madihaNo ratings yet

- Getaneh Et Al-2019-BMC PediatricsDocument11 pagesGetaneh Et Al-2019-BMC Pediatricszegeye GetanehNo ratings yet

- Answers To Module 2 of Urban Geography 3Document26 pagesAnswers To Module 2 of Urban Geography 3Johanisa DeriNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching PlanDocument8 pagesHealth Teaching Planrain َNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666149722000202 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S2666149722000202 MainALEXANDRE SOUSANo ratings yet

- Diet and FoodDocument2 pagesDiet and Foodneon333100% (2)

- Clup Final'08Document568 pagesClup Final'08Mae Elizabeth PugarinNo ratings yet

- FNCP PrioritizationDocument10 pagesFNCP PrioritizationSteven ConejosNo ratings yet

- Nutrition EducatorDocument13 pagesNutrition EducatorDarsan P NairNo ratings yet

- Beating Cancer With Nutrition - Optimal Nutrition Can Improve The Outcome in Medically-Treated Cancer Patients (PDFDrive)Document556 pagesBeating Cancer With Nutrition - Optimal Nutrition Can Improve The Outcome in Medically-Treated Cancer Patients (PDFDrive)Muhammad Mawardi Abdullah100% (12)

- Ajol File Journals - 475 - Articles - 141517 - Submission - Proof - 141517 5605 376681 1 10 20160805Document17 pagesAjol File Journals - 475 - Articles - 141517 - Submission - Proof - 141517 5605 376681 1 10 20160805myblackconfidentladiesNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter-5Document114 pages08 Chapter-5Lamico Dellavvoltoio100% (1)