Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rhetorical Persona

Uploaded by

Neo Keng HengCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rhetorical Persona

Uploaded by

Neo Keng HengCopyright:

Available Formats

Communication Monographs

ISSN: 0363-7751 (Print) 1479-5787 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcmm20

The rhetorical persona: Marcus Garvey as black

moses

B. L. Ware & Wil A. Linkugel

To cite this article: B. L. Ware & Wil A. Linkugel (1982) The rhetorical persona: Marcus Garvey

as black moses, Communication Monographs, 49:1, 50-62, DOI: 10.1080/03637758209376070

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03637758209376070

Published online: 02 Jun 2009.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 241

View related articles

Citing articles: 10 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcmm20

Download by: [NUS National University of Singapore]

Date: 14 September 2015, At: 23:20

THE RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS

BLACK MOSES

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

B. L. WARE

WIL A. LINKUGEL

The persona concept of traditional dramaturgy which refers to the masks worn by

actors in Greek and Roman theater can assist a rhetorical critic in explaining the

persuasive power of speakers who strongly remind their auditors of an archetypal

hero. When a speaker's rhetorical self becomes so closely associated with some set of

human experiences or ideas that it becomes virtually impossible for an audience to

think of one without the other, then that individual stands in a symbolic relationship

to those ideas or experiences and may wear the mask of a rhetorical persona.

Listeners, in such cases, impute to the speaker the ethos of their archetypal deliverer.

The purpose of this essay is to test this concept by applying it to Marcus Garvey, a

prototype Moses for Harlem blacks who were fervently awaiting a deliverer. The

essay is grounded in the formistic world view of Stephen C. Pepper. The Black Moses

Persona is treated as the transcendent form, and the factors of deliverance rhetoric

found in Garvey's speecheselection, captivity, and liberationare the particulars

that allow Garvey to participate in the form. The authors argue that it is precisely the

Black Moses Persona that explains why Garvey's importance survives him by thirty

years, despite the loss of his ideology's influence.

TyERSONA, in its strictest sense, is a of the actor qua person but to the characJL Latin word referring to the masks ter assumed by the actor when he dons

worn in Greek and Roman theater. The the mythical mask. We think this

Latin dictionary speaks of it as a "mask" persona conceptthe mask that is there

or "false face," covering the head, "worn before any person turns up to fill it

by actors."1 These masks symbolized a applies equally well to rhetorical critirole, an assumed character, or persona, cism.

and existed apart from individual actors.

Rhetorical personae reflect the aspiraWhen an actor put on one,of these tions and cultural visions of audiences

masks, he became the persona that the from which stems the symbolic construcmask symbolized. Robert Langbaum, tion of archetypal figures. An archetype,

literary critic, tells us that the term of course, is the original model, a protopersona implies the existence of a "mask type; it is the pattern from which copies

that is required by the mythical pattern, are made. Thus an archetypal figure is a

the ritual, the plotthe mask that is classic figure that exists either in history,

there before any person turns up to fill in myth, or literature and which has

it."2 Thus in traditional dramaturgy, gained such prominence in the minds of

persona does not refer to the personality people that rhetors who remind them of

the archetype will gain additional credibility as leaders. When a speaker's rheB. L. Ware is adjunct professor of law at Bates

College of Law, University of Houston. Wil A. torical self becomes so closely associated

Linkugel is professor of communication studies at with some set of human experiences or

the University of Kansas.

ideas that it becomes virtually impossible

1

See for example: Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: for auditors to think of one without the

At the Clarendon Press, 1968) or any other standard

other, then that individual stands in a

classical Latin dictionary.

symbolic relationship to those ideas or

2

Robert Langbaum, "The Mysteries of Identity,"

experiences. The speaker, in such cases,

The American Scholar, 34 (1965), 576.

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS, Volume 49, (March) 1982

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

THE RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

assumes the role of a rhetorical persona.

As observed above: The rhetorical

persona is not the rhetor qua person but

is an attributed character created by the

auditor's symbolic construction (and

implied assessment) of the rhetor. We

draw a sharp distinction here between

the rhetor's personal ethos and the ethos

represented by the rhetorical persona the

speaker assumes when he reminds the

listeners of its archetypal herothat

prototype in their psyches whom they

imagine will be their deliverer. The

character of the archetypal mask,

because of its peculiar importance to the

audience, will normally possess far

greater ethos than that of the actor wearing the mask. A rhetor, for example,

who strongly reminds auditors of a

prophetif a prophet is central to their

cultural visionwill be ascribed the

ethos of the audience's archetypal

prophet, perhaps an Elijah figure, or

any other prophet people imagine to be

their prototype deliverer. The speaker,

in that sense, transcends personal identity and becomes a truly charismatic

leader.

If we have learned nothing else from

George Herbert Mead, we can now see

that an individual's concept of self is a

social construction, that self-identity, as

Langbaum argues, "exists outside us in

the form of cultural symbols. In assimilating ourselves therefore, to these

symbols or roles or archetypes, we do not

lose the self but find it. Such symbols

or rhetorical personae naturally wield

moral authority over those who assist in

their construction. To achieve their

cultural vision, a people stands ready

symbolically to transcend its physical

reality and enter into the world of myth.

Such transcendence seems to be an

innate human propensity. Kenneth

Burke explains that "to say man is a

3

Langbaum, p. 586.

51

symbol-using animal is by the same

token to say that he is a 'transcending

animal.' " 4

PURPOSE OF T H I S ESSAY

We intend this essay as a threshold

inquiry into the nature of rhetorical

personae by examining Marcus Garvey

as a prototype Moses for Harlem blacks

who were fervently awaiting a deliverer.

We begin with a philosophical orientation to form. We understand a formistic

philosophy to be one in which the principal critical categories are (1) form, (2)

particulars, and (3) participation.5

Forms are two types: (1) immanent

and (2) transcendent. Immanent forms

are derived from "the simple commonsense perception of similar things."6

Immanent classification consists of descriptive grouping of objects which

"face-value" observation tells us look

alike, even though they may not be

entirely the same. Stephen C. Pepper

explains: "The world is full of things

that seem to be just alike: blades of grass,

leaves on a tree, a set of spoons, newspapers under a newsboy's arm, sheets of a

single ream of paper."7 In the world of

rhetoric, courtroom summation

speeches, for example, would easily cluster together in terms of face-value. We

prefer the term "genre" as an indication

of immanent formism. On the other

hand, there is a type of form Pepper

refers to as "transcendent." He tells us

that transcendent formism "comes from

two closely allied sources: the work of

the artisan in making different objects on

the same plan or for the same reason . . .

and the observation of natural objects

4

Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives (New York:

Prentice-Hall, 1950), p. 192.

5

Stephen C. Pepper, World Hypotheses: A Study in

Evidence (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1942), pp. 153-54,163-64.

6

Pepper, p. 151.

7

Pepper, p. 151.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

52

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

appearing or growing according to the

same plan."8 Such formism is transcendent in the sense that classification is

made on the basis of similarity to something, either to an archetype or norm,

that is not represented in the concrete

manifestation of the objects being classified. Whereas immanent formism is

grounded in Aristotle, transcendent

formism is fundamentally Platonic. We

find the term "archetype" to be indicative of criticism based upon transcendent

formism.

Particulars are those peculiar qualities that characterize the form. For

example, addresses we call sermons all

have the quality of being theologically

oriented and in an ultimate sense involve

the spiritual salvation of human souls.

They are commonly delivered in

churches, but that is not a necessary

quality because sometimes they may

occur out-of-doors on college campuses

or in a public building. Other addresses

may also have religious elements but

their ultimate motive is other than spiritual salvation. Participation is the category of terms used to explain the connection between the other two, that is, how

it is that specific discourse becomes associated with a certain rhetorical form.

This essay on Marcus Garvey as

Black Moses is an example of criticism

oriented toward transcendent formism.

The "Moses" persona exists independent of the rhetor in the minds of the

audience before communication occurs.

We argue that downtrodden peoples

tend to possess in common the mental

form of the "Moses" persona because of

their quest for deliverance. And that

rhetors who include in their rhetoric the

themes of Moseselection, captivity,

and liberationmay evoke that form.

Thus, Moses is the transcendent form.

The particulars of the Moses form are

8

Pepper, p. 162.

election, captivity, and liberation; Garvey, by employing these particulars in

his rhetoric, was able to participate in

the form. The result of this participation

was increased rhetorical impact. In no

small way the audience actively participated in their own persuasion because

Harlem blacks possessed cultural reservoirs of the substancethe awareness of

Moses' deliverance of oppressed people

and the hope of their own deliverance.

There is another type of rhetorical

form of importance to this essay. The

discourse that we term "deliverance" in

this essay can appropriately be labeled a

rhetorical genre.

There are of course limitations to

writing a piece grounded in formistic

philosophy. For example, many of

Garvey's speeches contain the themes of

deliverance rhetoric: election, captivity,

and liberation, while others do not. In

many respects Garvey's different rhetorical efforts are just thatvery different

from one another. One of the problems

with formistic philosophy is how to

explain this phenomenon, that is, how

artifacts can be dissimilar and yet be

perceived as similar and categorized

accordingly. No few philosophers have

struggled with these problems for centuries. We feel that despite this problem of

similarityor occasional dissimilarity

anyone who reads the composite of

Garvey's rhetoric carefully can discern

the qualities of election, captivity, and

liberation. Thus taken at its entirety,

Garvey's rhetoric, employing the particulars of deliverance rhetoric, is an example of transcendent formism because it

allowed him to participate in the Moses

form.

BACKGROUND OF GARVEY'S

LEADERSHIP

When Marcus Mosiah Garvey came

to Harlem in 1916 as the obscure head

of the embryonic Universal Negro

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

T H E RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

Improvement Association, until then an

organization enjoying in the main only

limited support in the West Indies, he

encountered problems familiar to all

who would lead oppressed groups since

the time of the biblical Moses. By what

signs would the black people know him

as their rightful leader? How could he

establish the necessary authority for the

people to follow him? To be sure, the

leadership problem was minimized by

certain social conditions existing in the

United States from 1916 to 1924, the

years during which Garvey found

American blacks so receptive to him as

their chieftain. The death of Booker T.

Washington in 1915 left the position of

titular head of the black community

temporarily vacant. The war years

resulted in considerable disruption of

blacks from their traditional life styles,

due to migration to industrial centers.

Furthermore, the rhetoric of democracy

surrounding American participation in

World War I created expectations of a

better life among all minorities, hopes

that were dashed after the Armistice by

the continuance of race riots and the

growth of the Ku Klux Klan.9

The social and economic frustrations

of the day, however, were not sufficient

in and of themselves to account for

Garvey's rise as a leader of the black

community. These disorders, though

perhaps more extreme than previously,

were not new experiences to the race. At

best, they suggest why the times were

ripe for the rise of a popular black

leader. They do not offer a critical,

definitive understanding of why Garvey

in particular became that leader. The

basis of Garvey's authority was the need

for a characterization of a Black Moses,

a persona, around which a true black

culture might form.

9

E. David Cronon, ed., Marcus Garvey (Englewood

Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1973), p. 5.

53

Garvey, through the appeal of his

rhetoric and the activities of the Universal Negro Improvement Association,

became a new leader of black

Americans. And as that new leader, in

James G. Frazer's terms, he wore the

"magic mask of Kingship [someone who

has authority over people]."10 The magic

face that Garvey wore, we contend, was

the Black Moses mask, a myth that gave

authenticity to his leadership. Michael

C. McGee, in speaking of the political

vision of mass man, notes, "In a sense

the myth contains all other stages of the

process; it gives specific meaning to a

society's ideological commitments; it is

the inventional source for arguments of

ratification among those seduced by

it.. . ." n We certainly find this to be true

of black Harlem and the Black Moses

Persona in Garvey's day. The power of

Garvey's appeal came from the fact that

he came to represent his people's archetypal hero. Edmund David Cronon

aptly discerned that Garvey "symbolized

the longings and aspirations of the black

masses."12

Certainly, when a rhetor's importance

survives him by thirty years despite the

loss of his ideology's influence, as

happened to Garvey's only a decade

after its inception, the basis for that

authority must be attributed to forces

beyond the discursive content of his

discourse.13 The study of Garvey's rheto10

Sir James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough, A Study

in Magic and Religion, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan,

1900); and Lectures on the Early History of Kingship

(London: Macmillan, 1905); Michael C. McGee, "In

Search of 'The People': A Rhetorical Perspective," The

Quarterly Journal of Speech, 61 (1975), pp. 235-49.

11

McGee, p. 243.

l2

Edmund David Cronon, Black Moses: The Story of

Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement

Association (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,

1955), p. xii.

13

Conservatively estimated, the Universal Negro

Improvement Association once numbered between one

and four million blacks throughout the world as

supporters. See "Two Prophets of Race Pride," Life, 6

Dec. 1968, p. 98. Garvey himself claimed a peak

membership worldwide of eleven million. See Emory

54

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

ric, consequently, promises insight into

the manner by which individuals take on

mythical qualities.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

T H E BLACK MOSES PERSONA: A

TRANSCENDENT FORM

Joseph R. Washington, Jr., argues

that it is an error to speak of a black

"culture" existing in the 1920's. He

contends that the experience of slavery,

working in combination with later political subjugation, precluded blacks from

developing appreciation of themselves as

a people sharing common viewpoints

and experiences. "Slavery, segregation,

and discrimination" had been used to

deny the black man participation in

white culture. Only the religious component of white culture was freely shared

by blacks. Blacks of Garvey's day

created a "half-culture," a number of

quasi-religious cults resulting from a

confluence of "African primitive survivals and white primitive evangelicalism."

Because the dominant white society

denied blacks the opportunity for a full

cultural experience, cults became the

focus for the black social order, inadequate though they were in providing

outlets for the human impetus toward

political and economic organization. For

blacks in the early part of the century,

"the religious order constituted the social

Tolbert, "Outpost Garveyism and the U.N.I.A. Rank

and File," Journal of Black Studies, 5 Mar. 1975, pp.

233-53. We are told the U.N.I.A. had over eight

hundred chapters in forty countries on four continents.

See Theodore C. Vincent, Black Power and the Garvey

Movement (Berkeley, Cal.: The Ramparts Press, n.d.),

p. 13. Despite this tremendous influence Garveyism

held at its zenith, ten years after its inception Garvey's

ideology, for all practical purposes, had lost its potency.

Perhaps this is what prompted one writer to observe

that "Garveyism did not have any permanent

influence." See Jabez Ayodele Langley, "Garveyism

and African Nationalism," Race, 11 (1969), p. 159. But

it is equally interesting to note that another writer has

proclaimed Garvey "the central figure in twentiethcentury Negro history." See Robert G. Weisbord,

"Marcus Garvey, Pan-Negroist: The View from

Whitehall," Race, 11 (1970), p. 419.

order." Consequently, it is not surprising to discover that the cults carried

within them beginnings of concern for

obtaining "authentic social, 'tribal,' or

community well-being." "The emotional fervor of black cults," concludes

Washington, "was the method and

assurance of social solidarity, a unity

which could be used for the superficial

or abiding good of black people."14

Regardless of the specific religious

teachings of particular cults, they all

taught the Exodus story, the story that

"has always been understood as the

prototype of racial and nationalistic

redemption."15 As many traditional spirituals, such as "Go Down, Moses," indicate, the American black man has long

identified with the plight of biblical

Israel. The slaves of the last century,

when away from their white overseers,

"worshipped the God who led the children of Israel out of Egyptian bondage,"

despite the white evangelists' preference

for sermons stressing obedience of

servant to master.16 The importance of

the Exodus story extended into this

century in the thinking of black religionists. The basis for such widespread

appeal of biblical Jewish travail to

modern day blacks is obvious, for as

Gayraud S. Wilmore observes:

The Egyptian captivity of the Jews, their miraculous deliverance from the hands of the Pharoahs,

and their eventual possession of the land promised

by God to their fathersthis was the inspiration

to which the Black religionists so often turned in

the dark night of his soul. Whenever the JudeoChristian tradition has been accessible to

oppressed peoples, the scenario of election, captivity and liberation has captured the imagination of

religious leadership.17

14

Joseph R. Washington, Jr., Black Sects and Cults

(Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972), p. 52.

15

Gayraude S. Wilmore, Black Religion and Black

Radicalism (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972), p.

52.

16

Bryan Fulks, Black Struggle (New York: Dell,

1969), p. 68.

17

Wilmore, p. 52. Italics added.

THE RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

Although Garvey was not dramatically called to leadership by a voice from

a burning bush, as was the biblical

Moses, to Garvey the call to lead his

people to freedom was clear and certain.

George Alexander McGuire asserts:

As to Moses of old, so to Garvey, there came a

clear call to duty and leadership. As a member of

a race free from the spirit of retaliation and

vindictiveness, with the desire to treat all

mankind as brothers without regard to differences

in creed, race or country, this young man, while

respecting ttie rights and admiring the progress of

alien people, resolved to make the material, political, social and spiritual development of his bloodkin wherever found, and the fostering within him

of the spirit of self-reliance, and self-determination, the sole consecrated purpose of his life, to the

end that the Negro might eventually take his

God-given place in the fraternity of man.18

Just as Moses of old used signs to

demonstrate to the Israelites that he had

been called to leadership, mostly in the

form of miracles stemming from his

staff, Garvey demonstrated to black

Harlem that he was an authentic leader.

He did not turn his staff into a snake or

cause hordes of frogs to emerge from the

Harlem River; nevertheless, Garvey's

activities must have seemed equally

miraculous to Harlem blacks. The

miraculous growth of the Universal

Negro Improvement Association, for

example, was an unprecedented phenomenon among Negro masses. By the

middle of 1919, Cronon reports, "there

is no doubt that large numbers of

Negroes were listening with ever

increasing interest to the serious black

18

George Alexander McGuire, "Preface," in Amy

Jacques Garvey, ed., Philosophy and Opinions of

Marcus Garvey, (New York: Universal Publishing

House, 1926), II, v; Hereafter cited as Philosophy and

Opinions. Garvey's mother, according to tradition,

sought to groom her son for the Moses role. Cronon

reports that "tradition has it that his mother, Sarah,

sought to give him the middle name of Moses in the

hope that like the biblical Moses, he would grow up to

lead his people. His father, a far-from-devout-stonemason, objected, and the parents compromised with

Mosiah." Cronon, Marcus Garvey, p. 1.

55

man whose persuasive words seemed to

point the way to race deliverance."19

Then in October of the same year

Garvey was attacked by an insane

former employee. Two bullets struck

him, one grazing his forehead, narrowly

missing his right eye, and the other

piercing his right leg. With blood

streaming down his face, the wounded

Garvey chased the assailant down the

street until the police apprehended the

assailant in the streets of Harlem.

Almost immediately, "The assault assumed heroic proportions in the Negro

press and Garvey became overnight a

persecuted martyr working for the salvation of his people."20 Then in January,

1918, Garvey established the Negro

World, a newspaper with "One Aim,

One God, One Destiny." It was priced

for low income blacks and quickly

became, according to one of Garvey's

sharpest critics, "the leading national

Negro Weekly."21 The front page of the

paper always carried a lengthy editorial

signed, "Your obedient servant, Marcus

Garvey, President General."

Garvey's signature as "President

General" was not without significance.

Early on he was concerned with questions such as:

"Where is the black man's Government?"

"Where is his King and his Kingdom?" "Where

is his President, his country, and his ambassador,

his army, his navy, his men of affairs?" I could

not find them, and then I declared, "I will help to

make them."22

He sought to give blacks self-regard

within the U.N.I.A. through an African

Legion, brilliantly attired in dark blue

uniforms and marching in parades with

well-drilled precision. Individual mem19

Cronon, Marcus Garvey, p. 44.

Cronon, Black Moses, p. 45.

Claude McKay, Harlem: Negro Metropolis (New

York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1940), p. 148.

22

"The Negro's Greatest Enemy," Sept. 1923, Philosophy and Opinions, II, 126.

20

21

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

56

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

bers of the Legion were given paramilitary titles. Garvey himself is commonly

pictured wearing a plumed helmet and

an ornately decorated uniform. Women

of the movement were organized into a

uniformed Black Cross Nurses group,

neatly garbed in white, and also well

trained in the skill of marching. This

paramilitary aspect of the U.N.I.A.

must have been evidence to Harlem

blacks of Garvey's call to leadership.

The greatest and perhaps most

convincing sign of Garvey's call to leadership was the Black Star Line.

Although the ships Garvey purchased

lacked seaworthiness, failing to deliver a

single emigrant to Africa, and although

the Black Star Line was constantly

enshrouded with debt and was the butt

of ridicule from Garvey's numerous critics, the enterprise belonged solely to

Negroes, was operated by Negroes, and

"gave even the poorest black the chance

to become a stockholder in a big business

enterprise."23 Black owned ships anchored in a harbor for all to see must

have assumed the proportions to Harlem

blacks of some of the miracles of Moses'

staff. Thus to millions of blacks in the

early 1920's Marcus Garvey personified

an archetypal deliverer necessary to

complete the construction of recent black

history as being equivalent to the prototype story of Jewish captivity. In order

to assume the Moses persona, all that

remained was for Garvey's rhetoric to

construct the necessary particulars of the

discourse of exiles: election, captivity,

and liberation.

DELIVERANCE RHETORIC:

PARTICULARS OF THE

TRANSCENDENT FORM

Election

The theme of election, the initial step

in the discourse of exiles, was expressed

23

Cronon, Black Moses, p. 57.

in Garvey's insistence upon a black

ethos, an affirmation and validation of

the race's worthiness. In the course of

many of his speaking engagements and

in his editorials that appeared in the

Negro World, the U.N.I.A. weekly

organ from 1918 to 1933, Garvey

espoused a black ethos by maintaining

that blacks should feel pride as a consequent of their racial membership. To

begin with, Garvey attempted to supply

blacks with a sense of racial history.

Reconstruction of the past so as to give

oppressed people legitimate origins is

essential to deliverance rhetoric. Making

reference to the. ancient African kingdoms, for example, Garvey recalled that

"when Europe was inhabited by a race

of cannibals, a race of savages, naked

men, heathens and pagans, Africa was a

people with a race of cultured black

men . . . ; men who, it was said, were like

the gods."24 On occasion, he reminded

his black audiences that "this race of

ours gave civilization, gave art, gave

science, gave literature to the world."25

Not content with recounting the

cultural achievements of the race,

Garvey was also fond of mentioning the

exploits of black armies and soldiers,

men who had fought creditably in

Mesopotamia during the Revolutionary

and Civil Wars in America, and most

recently at the battles of the Marne and

Verdun.26 In a similar vein, he praised

24

"The Future as I See It," Philosophy and Opinions,

1, 77. On another occasion Garvey proclaimed: "We are

satisfied to know . . . that our race gave the first great

civilization to the world; and, for centuries Africa, our

ancestral home, was the seat of learning; and when

blackmen who were only fit then for the company of the

gods, were philosophers, artists, scientists, and men of

vision and leadership, the people of other races were

groping in savagery, darkness and continental

barbarism." See "History and the Negro," Philosophy

and Opinions, II, 82.

25

Speech delivered on Emancipation Day at Liberty

Hall, New York City, Jan. 1, 1922, Philosophy and

Opinions, I, 80.

26

"The Principles of the Universal Negro Improvement Association," speech delivered at Liberty Hall,

New York City, Nov. 25, 1922, Philosophy and Opinions, II, 93, 99.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

THE RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

the "two million Negroes" who fought

with the Allies during World War I,

while "white fellow citizens of America

refused to fight."27 Naturally, he did not

neglect the experience of slavery: "You

who have not lost trace of your history

will recall the fact that over three

hundred years ago your fore-bears were

taken from the great Continent of Africa

and brought here for the purpose of

using them as slaves."28 And Garvey did

fear that some of those in his audience

had lost their history for he warned that

"the white world has always tried to rob

and discredit us of our history."29

Garvey's use of historical references

in his rhetoric has greater significance

than simply informing his audiences

about their past. No doubt such an

education in race history as Garvey

provides would serve in and of itself to

increase the pride people could take in

being black for one cannot be legitimate

in the present or future without a legitimate past. However, the frequency with

which Garvey relies upon detailed historical examples seems to involve more

than the simple transmittal of information. Specifically, he seems to be requesting his auditors to project themselves

into a number of diverse roles, to play

the part of black artists, soldiers, and

slaves from the past.

By identifying with the roles of blacks

in history, those who attended to

Garvey's rhetoric reorganized their past

cultural experience. On reading the

27

Statement on Arrest, Jan. 1922, Philosophy and

Opinions, I, 99.

28

Speech delivered on Emancipation Day at Liberty

Hall, New York City, Jan. 1, 1922, Philosophy and

Opinions, I, 79.

29

"Who and What Is a Negro?" April 26, 1923,

Philosophy and Opinions, II, 19. On another occasion

Garvey said: "White historians and writers have tried to

rob the black man of his proud past in history, and

when anything new is discovered to support the race's

claim and attest the truthfulness of our greatness in

other ages, then it is skillfully rearranged and credited

to some other unknown race or people." "History and

the Negro," Philosophy and Opinions, II, 82.

57

numerous historical references, we are

strongly reminded of Mead's account of

the nineteenth century romanticists,

writers who produced a literature

concerned with an idealized world and

who asked their readers to take on the

viewpoints of children, criminals,

knights errant, and other exotics.30

Langbaum effectively summarizes

Mead's thought:

According to Mead, the romanticists found themselves in a world in which public symbols had lost

moral authority. Their aim was to re-establish

values on an empiric basis. Since they felt analysis

could not yield values but could only destroy

them, the romanticists developed a projective

habit of mind. They came to know the world, not

from the outside by applying ideas to it, or by

passively responding to it, but by playing roles in

itby projecting themselves into nature, the past

and other people. In other words, they were

aware of themselves as inside, or as having organized, the experience they were perceiving. Thus

they came to know the object and the self in the

object, and it was through maintaining a sense of

continuity among the ever-increasing number of

their projected selves that they evolved a sense of

identity/1

In reconstructing their history, Garvey was actually providing his black

audiences with legitimate, honorable

self-identity. In identifying with blacks

in history, those who attended to

Garvey's rhetoric developed a sense of

their cultural unity, the consequence of

role playing that symbolic interactionists

such as Mead posit as the prerequisite

for the satisfactory construction of a selfidentity.32

Because of the importance of community in the black religious cults'

doctrines, as alluded to previously,

Garvey was able to create a racial identi-

30

George Herbert Mead, Movements of Thought in

the Nineteenth Century, ed. Merritt H. Moore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1936), p. 85.

31

Langbaum, pp. 569-70.

32

George Herbert Mead, The Philosophy of Act, ed.

Charles W. Morris (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1938), pp. 310-11, 448, 610-11, et passim.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

58

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

ty, or black ethos, through the use of

religious references as a complement to

historical examples. "Garvey's extreme

racial nationalism" wrote Cronon, "demanded fulfillment in a truly Negro

religion."33 Not accidentally, therefore,

/ the African Orthodox Church became a

major subsidiary organization to the

U.N.I.A. Among its tenets was a belief

in a black God and the Negro ancestry of

Christ. When challenged concerning the

"Negro ancestry of Christ," Garvey

denied claiming that Christ was a Negro

but that "Christ's ancestry included all

races, so that He was Divinity incarnate

in the broadest sense of the word."34

With God being a spirit, not a creature,

and Christ being multiracial, it was

possible for members of a race to see the

Divinity in terms of themselves, as, of

course, the white race had always done.35

Garvey proclaimed that "the highest

compliment we can pay our risen Lord

and Savior, is that of feeling that he has

created us as His masterpiece

When

it is said that we are created in His own

image, we ourselves reflect his greatness."36

This construction of a multiracial

God was no doubt a significant contribution in and of itself to the black ethos.

However, as a result of the emphasis

upon identification with a multiracial

Christ, all who played the historical

roles depicted by Garvey's rhetoric, no

matter how diverse or exotic those roles

might be, additionally participated in

the unifying experience of religion.

33

Cronon, Black Moses, p. 178.

Rollin Lynde Hartt, "The Negro Moses," Independent and Weekly Review, 26 Feb. 1921, p. 205.

35

Amy Jacques Garvey wrote to E. David Cronon:

"It is really logical that although we all know God is a

spirit, yet all religions more or less visualize Him in a

likeness akin to their own race. . . . Hence it was most

vital that pictures of God should be in the likeness of the

(Negro) race." Cronon, Black Moses, p. 178.

36

"The Resurrection of the Negro," Easter Sunday

sermon delivered at Liberty Hall, New York City, Apr.

16, 1922, Philosophy and Opinions, I, 91.

34

Whether an individual audience member chose to identify himself with a

heroic solider in ancient Mesopotamia,

to assume the role of a cultured scholar

in Egypt, or to view himself as a lowly

slave in America, the religious references

in Garvey's discourses emphasized "the

chosen role" as one of a black man who

personified the perfection of a black

God. Furthermore, Garvey argued that

it was only after the recognition that

blacks too reflected God, that men, both

black and white, could come to a "better

understanding of self, as individuals,"

and that any white man could "realize

his true kinship with his Creator and be

what his God expected him to be."37

Consequently, he insisted that there

could be no salvation for the white man

until the "powerful" races recognized

the participation of blacks in divinity,

until the "strong" peoples ceased abusing and oppressing God's creations as

manifested in black men.38 The religious

salvation of whites became, in a sense,

dependent upon blacks.

Through reversal of the dependency

relationship between blacks and whites,

Garvey subtly brings the particulars of

election to rhetorical completion. What

could be more complimentary to the

black ethos than the implicit suggestion

that the salvation of the white race was

tied to the deliverance of black people

from centuries of injustice and that the

black race didn't have to depend on

whites at all? In effect, Garvey's

repeated contention that blacks are

God's "masterpiece," reduces to the

equivalent of saying that blacks are

elected by God as His chosen people.

And the subtlety with which Garvey

37

"Christ the Greatest Reformer," speech delivered at

Liberty Hall, New York City, Dec. 24, 1922, Philosophy and Opinions, II, 31.

38

"Christ the Greatest Reformer," speech delivered at

Liberty Hall, New York City, Dec. 24, 1922, Philosophy and Opinions, II, 31.

THE RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

treats the theme of election, his failure to

refer overtly to blacks as being "chosen,"

is itself not without rhetorical significance. Washington makes the point:

Precisely because the Negro has not called his

people "chosen," it is in keeping with the faith

and Negro Spirituals to perceive them as chosen.

The idea of "chosen" is a religious interpretation

of a people's experience. Indeed, Negroes would

not wish to be calledand would actively resist

beingthe "chosen people" were they consciously to understand and accept the biblical

meaning of being poured out as "intercession for

transgressors." But just as they have neither

known nor (consciously) accepted it, this is their

history: For it is through their experience that the

presence of God in all our midst can be affirmed.

Through their suffering "we are healed"black

and white together.3'

Captivity

Reconstruction of the past and the

deprecation of present conditions are

essential to deliverance rhetoric for it

allows the rhetor to point to a reformed,

purified future. Thus a second pattern of

deliverance discourse is deprecation of

the present. Contrary to his treatment of

the election theme, Garvey's speeches

and editorials display little delicacy in

the development of the captivity theme.

"At no time in the history of the world,"

Garvey bluntly insisted on one occasion,

"for the last five hundred years, was

there ever a serious attempt made to free

negroes."40 He emphasized at times the

history of blacks with respect to bondage

in the strictest sense of the term, remarking that his race had been forced "to

endure the tortures and sufferings of

slavery for two hundred and fifty

years."41 At other times, his emphasis

39

Joseph R. Washington, Jr., The Politics of God

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1967), p. 156.

40

Speech delivered at Liberty Hall, New York City,

during Second International Convention of Negroes,

Aug. 1921, Philosophy and Opinions, 1,94.

41

Speech delivered at Emancipation Day at Liberty

Hall, New York City, J a n . 1, 1922, Philosophy and

Opinions, I, 80-81.

59

was upon the more insidious servitude

experienced by his race in this century,

and he warned that blacks "have been

camouflaged into believing that we were

made free by Abraham Lincoln. That

we were made free by Victoria of

England, but up to now we are still

slaves, we are industrial slaves, we are

social slaves, we are political slaves."42

The full extent of the black race's

enslavement in this century, however,

was seen as going far beyond economic,

social, and political deprivation. More

important than material goods and political equality was the denial of opportunity for blacks to prove themselves as a

race. 7In an open letter to white

Americans appearing in the Negro

World, Garvey pleaded with whites not

to encourage Negroes "to believe that

they will become social equals and leaders of the whites in America, without

first on their own account proving to the

world that they are capable of evolving a

civilization of their own. The white race

can best help the Negro by telling him

the truth and not by flattering him into

believing that he is as good as any white

man without first proving the racial,

national, constructive metal of which he

is made."43

A people, having a shared cultural

vision, should have common problems.

The strongest identification comes from

a threat to the people as a whole. Racial

captivity, because it is inflicted upon one

as a result of membership in a group,

emerges as a theme that maximizes

unity of the people. By stressing the

captivity theme, Garvey made apparent

the need for leaders who were liberators.

The threat of enslavement, of course,

readily implied the need for unification

42

Speech delivered at Liberty Hall, New York City,

during Second International Convention of Negroes,

Aug. 1921, Philosophy and Opinions, I, 95.

43

"An Appeal to the Soul of White America," Philosophy and Opinions, II, 5.

60

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

of the people under one leaderGarvey,

because he symbolized the Black Moses.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

Liberation

The third theme of the rhetoric of

deliverance is to affirm a viable salvation, a "new" future. The conditions of

liberation must stand in sharp contrast

to that of captivity. The biblical

Israelites, for example, were told they

were headed to a land where the streams

flowed with milk and honey.

For Garvey, the theme of black

captivity naturally lead to the liberation

theme. As for economic liberation,

Garvey's efforts were devoted to organizing business enterprises such as the

Black Star Line steamship company.

Garvey was convinced that only through

such ventures could blacks become free.

In defense of his business activities

before a white jury trial for mail fraud,

he asserted:

The Universal Negro Improvement Association

and the Black Star Line employs thousands of

black girls and black boys. Girls who could only

be washer women in your homes, we made clerks

and stenographers of them in the Black Star

Line's office. You will see that from the start we

tried to dignify our race.44

Although praise of economic enterprises was quite prevalent in Garvey's

rhetoric, he devoted considerably more

attention to the Pan-African component

of his ideology. In the days shortly after

World War I when the victorious Allies

were creating ethnically based homelands in Europe with some ease, it is not

unbelievable that they might have carved

a place for blacks in Africa. Garvey

certainly believed that the white race

owed this much to his people for he

remarks that "as black men for three

centuries have helped white men build

America, surely generous and grateful

44

"Mr. Garvey's Address to Jury at Close of Trial,"

Philosophy and Opinions, II, 184.

white men will help black men build

Africa." 45 Nevertheless, for most

American Negroes the important appeal

of Garvey's rhetoric was not its "promised land" feature, and it was clearly not

Garvey's intention, as so often is

presumed, to transport all the blacks

scattered throughout the world back to

Africa. He could not more clearly have

stated his point than when he said:

The thoughtful and industrious of our race want

to go back to Africa, because we realize it will be

our only hope of permanent existence. We cannot

all go in a day or year, ten or twenty years. It will

take time under the rule of modern economics, to

entirely or largely depopulate a country of a

people, who have been its residents for centuries,

but we feel that with proper help for fifty years,

the problem can be solved. We do not want all the

Negroes in Africa. Some are no good here, and

naturally will be no good there.46

In other words, Garvey saw Africa as an

opportunity for the black race to build a

nation of its own, as a chance to prove

that his people were as capable as other

races. Africa was to be the spiritual

homeland for blacks, and the culture

they would build there would serve as

ultimate proof of their equality and

worthiness to which they could point in

justification of their claims for liberation

in other countries. The final liberation

would come only when:

As children of captivity we look forward to a new

day and a new, yet ever old, land of our fathers,

the land of refuge, the land of the Prophets, the

land of the Saints, and the land of God's crowning

glory. We shall gather together our children, our

treasures and our loved ones, and, as the children

of Israel, we shall also stretch forth our hands and

bless our country.47

45

Speech delivered at Madison Square Garden, New

York City, March 16, 1924, Philosophy and Opinions,

II, 121.

46

Speech delivered at Madison Square Garden, New

York City, March 16, 1924, Philosophy and Opinions,

II, 122.

47

Speech delivered at Madison Square Garden, New

York City, March 16, 1924, Philosophy and Opinions,

II, 121.

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

T H E RHETORICAL PERSONA: MARCUS GARVEY AS BLACK MOSES

Robert Hughes Brisbane, Jr., has

observed, "Under the stimulus of

Garveyism, Negro nationalism became

creative, constructive, boastful, and definitely more chauvinistic."48

Garvey's rhetorical works are marked

by three strategies: election, captivity,

and liberation. Taken separately, they

are ideological appeals in the Burkeian

sense. But in Garvey's rhetoric, they

become structured into a temporal

sequence, that of the prototype story of

Jewish captivity that is both uniquely

and universally appealing to oppressed

peoples. Burke reminds us that sequentially arranged "terms" that "so lead

into one another that the completion of

each order leads to the next" are "ultimate" or "mystical" or mythical

terms.49

The perception of Garvey as a Black

Moses was the artifact of interaction

between rhetor and his audiences.

Garvey's rhetoric provided his audiences

access to the constituent ideas of the

archetypal story of racial deliverance.

Because Garvey's rhetoric fused the

black experience with that of a New

Israel, his auditors perceived him as a

Black Moses, a type of cultural symbol

that ultimately subsumed and stood for

the ideas of election, captivity, and liberation. As the numerous instances of

references to Garvey as "Black Moses"

by. the press of his day indicates, the

Black Moses persona symbolized the

cultural vision of his auditors.50 In the

48

Robert Hughes Brisbane, Jr., "Some New Light on

the Garvey Movement," Journal of Negro History,

36(1951), p. 59.

49

Burke, Motives, p. 189.

50

Cronon suggests that "Garvey appeared fortuitiously at a time when the Negro masses were awaiting

a black Moses, and he became the instrument through

which they could express their longings and deep

discontent." Cronon, Marcus Garvey, p. 168. For

examples of the use of it by the press see: World's Work,

Dec. 1920, p. 153; Independent and Weekly Review, 26

Feb. 1921, p. 205; Literary Digest, 19 Mar. 1921, p. 48;

Liberator, Apr. 1922, p. 8; and The Nation, 18 Aug.

1926, p. 147.

61

case of black auditors, who we should

recall were dependent upon Garvey for

some measure of their racial and selfidentities, the Black Moses persona held

considerable authority, so much so that

Garvey was considered to be "without

peer as a mobilizer of black masses."51

Finally, as references to Garvey as the

"Black Moses" in present day historical

writings would indicate, it is the persona

that lingers on long after his ideology

has become ignored. When we find this

kind of crustaceous image, this "mask"

that only awaits another to fill it, we

would argue that we can best refer to it

as a rhetorical persona.

T H E RHETORICAL PERSONA AND

FORMISTIC CRITICISM

We think that the rhetorical persona

construct is of value to critics interested

in the formistic criticism52 of rhetorical

artifacts, i.e., to students dedicated to

"disclosing the elements common to

many discourses rather than the singularities of a few"53 in an attempt to

identify genres or forms of public

address. The symbolic construction of

archetypal personae in the minds of

auditors entails the discernible factors

useful in assessing rhetoric otherwise hot

easily explained. How else is one to

explain the impact of Marcus Garvey,

for example? The Moses form was a

unique motive force to blacks in Harlem

in the early 1920's. Because audiences

with a strong cultural visionsuch as

Harlem blacks in Garvey's timeare

prone to impute mystical qualities

51

Washington, Black Sects and Cults, p. 128.

For a discussion of the philosophical foundations of

formistic criticism, see B. L. Ware, "Theories of

Rhetorical Criticism as Argument," Diss. University of

Kansas 1972, esp. ch. III, "The Paradoxical World of

Formistic Criticism."

53

Edwin Black, Rhetorical Criticism: A Study in

Method (New York: Macmillan, 1965), pp. 176-77.

52

Downloaded by [NUS National University of Singapore] at 23:20 14 September 2015

62

COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPHS

those of an archetypal figureto individual rhetors who fit their cultural

vision, we as critics have the task of

explaining and assessing how these

visions interface with the characteristics

of a speaker and how his rhetoric fulfills

the attributes of that archetype.

The formistic critic, therefore, is one

who faces a dual task. First, it is incumbent to delineate and explain forms or

genres of public address that are useful

to the critical purpose.54 Second, there

must be an accounting of the phenomenon experienced by auditors when

rhetors themselves become rhetorical

forms or personae. In the instance of

Garvey, we contend that criticism

reveals a rhetorical persona created

through the effective use of the particulars of address we term deliverance rhetoric, or the discourse of exiles. The

gravamen of our argument is that the

formistic study of rhetoric, in addition to

the causal study exemplified by neoAristotelians or to the study oriented

toward process as practiced by

Burkeians, provides useful critical insight. We offer this study as an example

of an heretofore unexplored aspect of

formistic criticismthe use of a genre of

rhetoric resulting in the formation of a

rhetorical persona. This study of Garvey

suggests that rhetorical personae may

typically be associated with a genre of

rhetoric, as Garvey himself relied upon

deliverance rhetoric. We are aware of no

evidence at this time suggesting that each

54

We have elsewhere discussed a critical methodology

for studying forms of public address. See B. L. Ware

and Wil A. Linkugel, "They Spoke in Defense of

Themselves: On the Generic Criticism of Apologia,"

The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 59 (1973), pp. 27383.

genre results in an identifiable persona,

a proposition that awaits further study.

We conclude, therefore, simply that the

construct of the rhetorical persona is

useful to the formistic critic when

confronted with a rhetor who takes on

mythical qualities.

The technique for discovering a

rhetorical persona is to identify a rhetor

who uniquely represents or symbolizes

an historic period, a movement, or

world-view.55 The "rhetorical mask to

be filled" by a rhetor often stems from

the aesthetic realm of literature or myth,

or from an analogous historical episode.

Then if the audience ascribes to that

speaker the qualities of an archetypal,

transcendent form, the persona the

speaker assumes will have inherent

persuasive connotations deep within the

cultural psyche of that audience. We

must remind ourselves, however, that

the task of the critic does not end with

the identification of rhetorical personae.

There remains the important function of

explaining and assessing the manner in

which a speaker's rhetoric effects the

transformation of the individual into a

transcendent form. Such formistic criticism should fulfill the raison d'etre of the

critical artthe assessment of instances

of rhetoric and the extension of knowledge of critical and rhetorical theory.

55

There are rhetorical personae in recent times other

than Garvey. We think that some rhetors such as

Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill are easily

discernible by critics as instances in which individuals

have come to symbolize a national myth through transformation into rhetorical personae. The discerning critic, properly sensitized to the usefulness of the persona as

a critical construct, would have little difficulty in using

that construct to explain and evaluate the rhetoric of the

myriad number of cult leaders endemic to any time

period. The Rev. Jim Jones, the central figure of the

Jonestown, Guiana, tragedy in 1979, challenges the

critic to explain the perversion of the Moses story.

You might also like

- The Heart of the Pearl Shell: The Mythological Dimension of Foi SocialityFrom EverandThe Heart of the Pearl Shell: The Mythological Dimension of Foi SocialityNo ratings yet

- Thinking of Others: On the Talent for MetaphorFrom EverandThinking of Others: On the Talent for MetaphorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Imposing Fictions: Subversive Literature and the Imperative of AuthenticityFrom EverandImposing Fictions: Subversive Literature and the Imperative of AuthenticityNo ratings yet

- Cixous - Laugh of The MedusaDocument99 pagesCixous - Laugh of The Medusaguki92No ratings yet

- Archetypes, Rhetoric and Characters: Northrup Frye's CriticismDocument5 pagesArchetypes, Rhetoric and Characters: Northrup Frye's CriticismShubhra UppalNo ratings yet

- Tainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rhetoric of Fallenness in Victorian CultureFrom EverandTainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rhetoric of Fallenness in Victorian CultureNo ratings yet

- Important Terms/Concepts in Feminist Theories: SubjectDocument15 pagesImportant Terms/Concepts in Feminist Theories: SubjectNitika SinglaNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryFrom EverandAnthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryNo ratings yet

- Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and ActionFrom EverandHuman Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Life of Wisdom in Rousseau's "Reveries of the Solitary Walker"From EverandThe Life of Wisdom in Rousseau's "Reveries of the Solitary Walker"No ratings yet

- Haunted by Christ: Modern Writers and the Struggle for FaithFrom EverandHaunted by Christ: Modern Writers and the Struggle for FaithRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Oxford Handbook of The SelfDocument26 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of The SelfVicent Ballester GarciaNo ratings yet

- FEARMORPHOSIS: MAN IS A FEAR SISYPHUS BEING WATCHED BY PANOPTICONSFrom EverandFEARMORPHOSIS: MAN IS A FEAR SISYPHUS BEING WATCHED BY PANOPTICONSNo ratings yet

- Fictions of Authority: Women Writers and Narrative VoiceFrom EverandFictions of Authority: Women Writers and Narrative VoiceNo ratings yet

- On Keeping "Persons" in The Trinity: A Linguistic Approach To Trinitarian ThoughtDocument19 pagesOn Keeping "Persons" in The Trinity: A Linguistic Approach To Trinitarian ThoughtLIto LamonteNo ratings yet

- Theories of LiteratureDocument8 pagesTheories of LiteratureSheena JavierNo ratings yet

- Cut of the Real: Subjectivity in Poststructuralist PhilosophyFrom EverandCut of the Real: Subjectivity in Poststructuralist PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Imagine No Religion: How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient RealitiesFrom EverandImagine No Religion: How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient RealitiesNo ratings yet

- Character: Three Inquiries in Literary StudiesFrom EverandCharacter: Three Inquiries in Literary StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 14 Psychoanalytic CriticismDocument16 pages14 Psychoanalytic CriticismAhsan KamalNo ratings yet

- Parables and Metaphor Reveal TheologyDocument16 pagesParables and Metaphor Reveal TheologyLazar PavlovicNo ratings yet

- Giving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming TheomaniaFrom EverandGiving Beyond the Gift: Apophasis and Overcoming TheomaniaNo ratings yet

- Hans Urs Von Balthasar - Concept of Person in TheologyDocument14 pagesHans Urs Von Balthasar - Concept of Person in Theologyineszulema100% (1)

- Influence Of Psychophysiological Specifics Of A Leader On The Style Of Political Decision-MakingFrom EverandInfluence Of Psychophysiological Specifics Of A Leader On The Style Of Political Decision-MakingNo ratings yet

- Atmosphere, Mood, Stimmung: On a Hidden Potential of LiteratureFrom EverandAtmosphere, Mood, Stimmung: On a Hidden Potential of LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Post-Structuralism TheoryDocument7 pagesPost-Structuralism TheoryharoonNo ratings yet

- Volition's Face: Personification and the Will in Renaissance LiteratureFrom EverandVolition's Face: Personification and the Will in Renaissance LiteratureNo ratings yet

- On Diaspora: Christianity, Religion, and SecularityFrom EverandOn Diaspora: Christianity, Religion, and SecularityNo ratings yet

- The Royal Remains: The People's Two Bodies and the Endgames of SovereigntyFrom EverandThe Royal Remains: The People's Two Bodies and the Endgames of SovereigntyNo ratings yet

- Character: The History of a Cultural ObsessionFrom EverandCharacter: The History of a Cultural ObsessionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Devotion: Three Inquiries in Religion, Literature, and Political ImaginationFrom EverandDevotion: Three Inquiries in Religion, Literature, and Political ImaginationNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Narrative: Essays on History, Literature, and Theory, 2007–2017From EverandThe Ethics of Narrative: Essays on History, Literature, and Theory, 2007–2017No ratings yet

- 1) Definition, History-StructuralismDocument12 pages1) Definition, History-StructuralismRifa Kader DishaNo ratings yet

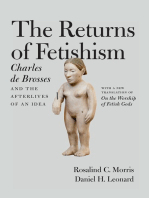

- The Returns of Fetishism: Charles de Brosses and the Afterlives of an IdeaFrom EverandThe Returns of Fetishism: Charles de Brosses and the Afterlives of an IdeaNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Self and the Other: A Levinasian Reading of the Postmodern NovelFrom EverandEthics, Self and the Other: A Levinasian Reading of the Postmodern NovelNo ratings yet

- DoppelgängerDocument11 pagesDoppelgängerMaria PucherNo ratings yet

- Structuralism: (Ferdinand de Saussure)Document4 pagesStructuralism: (Ferdinand de Saussure)Chan Zaib Cheema50% (4)

- The Book of Primal Signs: The High Magic of SymbolsFrom EverandThe Book of Primal Signs: The High Magic of SymbolsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Middling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyFrom EverandMiddling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyNo ratings yet

- The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay of Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near EastFrom EverandThe Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay of Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near EastRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Summary and Analysis of How to Read Literature Like a Professor: Based on the Book by Thomas C. FosterFrom EverandSummary and Analysis of How to Read Literature Like a Professor: Based on the Book by Thomas C. FosterRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Rereading Doris Lessing: Narrative Patterns of Doubling and RepetitionFrom EverandRereading Doris Lessing: Narrative Patterns of Doubling and RepetitionNo ratings yet

- On the Nature of Marx's Things: Translation as NecrophilologyFrom EverandOn the Nature of Marx's Things: Translation as NecrophilologyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Radical Apophasis: The Internal “Logic” of Plotinian and Dionysian NegationFrom EverandRadical Apophasis: The Internal “Logic” of Plotinian and Dionysian NegationNo ratings yet

- The Secrets of Personality Development and Creating a Beautiful Character: Character Power: New Revised EditionFrom EverandThe Secrets of Personality Development and Creating a Beautiful Character: Character Power: New Revised EditionNo ratings yet

- Public Space Design ManualDocument296 pagesPublic Space Design ManualMarina Melenti100% (2)

- Examiners' Report: Unit Ngc1: Management of Health and Safety September 2018Document13 pagesExaminers' Report: Unit Ngc1: Management of Health and Safety September 2018khalidNo ratings yet

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan Cot1Document4 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan Cot1Grizel Anne Yutuc OcampoNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Environmental Literacy in ChinaDocument394 pagesAssessment of Environmental Literacy in ChinaJoyae ChavezNo ratings yet

- Zakir Naik Is A LiarDocument18 pagesZakir Naik Is A Liar791987No ratings yet

- l2 Teaching Methods and ApproachesDocument22 pagesl2 Teaching Methods and ApproachesCarlos Fernández PrietoNo ratings yet

- 2.diffrences in CultureDocument39 pages2.diffrences in CultureAshNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan of Landforms and Venn DiagramDocument5 pagesLesson Plan of Landforms and Venn Diagramapi-335617097No ratings yet

- WIDDOWSON WIDDOWSON, Learning Purpose and Language UseDocument6 pagesWIDDOWSON WIDDOWSON, Learning Purpose and Language UseSabriThabetNo ratings yet

- 6.1, The Rise of Greek CivilizationDocument18 pages6.1, The Rise of Greek CivilizationLeon GuintoNo ratings yet

- Marketing CHAPTER TWO PDFDocument48 pagesMarketing CHAPTER TWO PDFDechu ShiferaNo ratings yet

- My Lesson FinalsDocument7 pagesMy Lesson Finalsapi-321156981No ratings yet

- ANALYSIS OF ARMS AND THE MAN: EXPLORING CLASS, WAR, AND IDEALISMDocument3 pagesANALYSIS OF ARMS AND THE MAN: EXPLORING CLASS, WAR, AND IDEALISMSayantan Chatterjee100% (1)

- Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-25443429386% (7)

- A Study On CSR - Overview, Issues & ChallengesDocument14 pagesA Study On CSR - Overview, Issues & ChallengesRiya AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Grammar Within and Beyond The SentenceDocument3 pagesGrammar Within and Beyond The SentenceAmna iqbal75% (4)

- 1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and TheDocument409 pages1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and Thegladio67No ratings yet

- BVDoshi's Works and IdeasDocument11 pagesBVDoshi's Works and IdeasPraveen KuralNo ratings yet

- Heidegger - Being and TimeDocument540 pagesHeidegger - Being and Timeparlate100% (3)

- 5 Lesson Unit OnDocument9 pages5 Lesson Unit OnAmber KamranNo ratings yet

- LTS-INTRODUCTIONDocument34 pagesLTS-INTRODUCTIONAmir FabroNo ratings yet

- Management Student Amaan Ali Khan ResumeDocument2 pagesManagement Student Amaan Ali Khan ResumeFalakNo ratings yet

- Religion in Roman BritianDocument294 pagesReligion in Roman Britiannabializm100% (11)

- Learnenglish ProfessionalsDocument2 pagesLearnenglish ProfessionalsVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- BL Ge 6115 Lec 1923t Art Appreciation PrelimDocument5 pagesBL Ge 6115 Lec 1923t Art Appreciation PrelimMark Jefferson BantotoNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Essay Writing - Nov.4-Nov.9Document20 pagesPersuasive Essay Writing - Nov.4-Nov.9mckenziemarylouNo ratings yet

- The Hippies and American Values by Miller, Timothy SDocument193 pagesThe Hippies and American Values by Miller, Timothy Sowen reinhart100% (2)

- Career Development Program ProposalDocument9 pagesCareer Development Program Proposalapi-223126140100% (1)

- Masud Vai C.V Final 2Document2 pagesMasud Vai C.V Final 2Faruque SathiNo ratings yet

- The Cultural Diversity of BrazilDocument1 pageThe Cultural Diversity of BrazilInes SalesNo ratings yet