Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: Karlsson

Uploaded by

macOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: Karlsson

Uploaded by

macCopyright:

Available Formats

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 1984, 25, 51-63

Introduction to phenomenological psychological research

JENNIFER BULLINGTON and GUNNAR KARLSSON

Department of Psychology, University of Stockholm. Stockholm, Sweden

Bullington. J. & Karlsson, G . : Introduction to phenomenological psychological research.

Scandinmian Journal of Psychology, 1984.25, 51-63.

This report presents an introduction to phenomenological psychological research. A brief

theoretical section on Husserls phenomenological philosophy is followed by a comparison

between phenomenological psychology and traditional psychology and a tutorial example

of the phenomenological method in psychological research. The authors argue for the

necessity of a phenomenological descriptive approach to psychological research which

seeks to discover the meaning of various phenomena using the descriptions of subjects

experiences. The results of a phenomenological psychological study consist of a structural

description of the phenomenon in question, which basically describes the what and how of

a specific phenomenon rather than the explanatory why.

G . Karlsson. Department of Psychology, University of Stockholm. S-106 91 Stockholm,

Sweden.

INTRODUCTION TO HUSSERLS PHENOMENOLOGY

Phenomenology started with the works of Edmund Husserl. For that reason we will begin

our dicussion with Husserls phenomenology, at least briefly, in order to introduce the

main topic of this paper; phenomenological psychology. We will try to show how a

philosophical grounding in phenomenology can be the basis for an empirical human

science (as opposed to a natural scientific) approach to psychology.

Phenomenology is the systematic investigation of subjectivity. Subjectivity, for Husserl,

was the indubitable ground of experience; that I am now having the experience of seeing a

blue thing, for example, is lived with a certitude I cannot doubt. The aim of phenomenology is to study the world as it appears to us in and through consciousness. This is a radical

move away from the objective sciences which take as their subject matter the so-called

objective reality of the world, which is supposed to exist independently of consciousness and subjectivity. Phenomenology wishes to examine the very ground of such a world,

which is precisely consciousness and human subjectivity. Husserls point concerning the

natural sciences was that although the objective world described by physics and

chemistry is a derived, constructed world, science wishes to place this constructed world

as prior or more real than the subjectively lived world. Husserl did not wish to

disparage the findings of the natural sciences, but he maintained that they have no place in

phenomenology, which places lived experience prior to scientific formulations abour lived

experience. It is for this reason that phenomenology makes no use of natural scientific

methods as such. Because our subject matter as phenomenologists is prior to scientific

formulations about an objective world, we cannot use these very formulations to

account for our field of inquiry. If we wish to study consciousness and subjectivity, we

cannot begin by assuming the objective reality of the world which consciousness itself

posits. In order to study the realm of subjectivity, Husserl had to develop a completely

new method, which he called the phenomenological reduction.

THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL REDUCTION

The reduction is the cornerstone of phenomenology. Before we can begin our analyses of

consciousness, we must perform the reduction in order to take ourselves out of the

S2

J . Bullington and G. Karlsson

Scand J Psvchol ZS (1984)

"natural attitude". The natural attitude is the way we take for granted the existence of a

transcendent world, which seems to exist independently of consciousness. This attitude

has a long philosophical history; it underlies all natural scientific causal explanations of

perception and cognition. Basically, it asserts that there exists a world which impinges on

me (my "mind") and caicses me to have this or that experience (sensation). We may

further describe the natural attitude as the way in which the world seems to spread itself

out before us, apparently indifferent to our intending to it. In short, the natural attitude is

our belief in the existence of the real, transcendent world. It is called the "natural"

attitude because it is our unreflective, natural way of being in the world. To believe in the

reality character of the world has its roots in the very nature of perception itself. "To have

something real primordially given, and to 'become aware' of it and 'perceive' it in simple

intuition are one and the same thing" (Husserl, 1962, p. 45, first published in German

1913). When we perform the phenomenological reduction, it is this belief in the reality

character of the world which we must suspend, or "bracket". It is not that we doubt the

existence of the world (for my direct experience informs me that the world, of course, is

always there), but by putting the transcendent object in brackets, we are able to underline

the way in which the object appears to consciousness. Thus, the reduction is not a

destruction of the world, but rather, a way in which to focus upon the constituting of the

world.

According to Husserl, every such phenomenological reduction can also be an eidetic

reduction. An eidetic reduction is the move from the world of facts (or particulars) to the

world of intended invariant meanings (or essences). Briefly, the eidetic reduction is our

natural ability to intuit or prereflectively grasp the essence of a thing through its particulars. Every phenomenological reduction aims ultimately at an eidetic reduction, but every

eidetic reduction need not be a phenomenological reduction. We may grasp essences

through particulars in the natural attitude. However, every time we perform a phenomenological reduction and attempt to do phenomenology, we must make this eidetic move as

well. To sum up. in the natural attitude the world that lies in front of us conceals the acts of

consciousness which posit the world. In the phenomenological attitude (by implementing

the phenomenological reduction) we can discover two poles of consciousness; noesis and

noema, which make up the most unique feature of consciousness; namely, intentionality.

Basically, "intentionality" means that consciousness is always consciousness of something.

Let us assume that we have now performed the phenomenological reduction. Under the

reduction we can discern two poles of experience: the subjective pole which Husserl calls

noesis-the acts of consciousness, and we also discover the correlate of every conscious

act, which Husserl calls the noema-the object as intended, as meant, as perceived.

Noesis always refers to the positing acts, or in metaphorical language, to the "streaming"

of consciousness towards the world. On the other hand, the noema refers to that-which-ispositeaintended. The noematic pole is that which we used to call the "real world" in the

natural attitude. Husserl's analyses show that what we used to call the "real object"

presents itself to consciousness as a flowing of views, each one flowing and blending into

the next. For this reason we can also call the noema a "system of appearances". To clarify

the noema with an example, let us say that I now have the experience of this cup in front of

me. What my perceptual experience gives me is a perspectival view of the cup from here

and now. I can now see the front of the cup. I perceive that it is round, although I cannot

see the back of the cup. As I move around the cup, I can now see the back, which I could

not see before. All these perspectival views point to a whole beyond any one perspective.

This whole, this system of appearances is the noema. These appearances mutually confirm

one another and go together coherently to give me the whole cup at once. This is a paradox

Sand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

Plienornenological psychology

of perception: that consciousness gives us a flow of apperearances which seem to point to

a self-same object which furthermore seems to be independent of appearance. In short,

consciousness gives us appearances which seem to be independent of their appearances!

And how is this possible? Here we have an example of a phenomenological formulation of

a problem of perception which could never arise were we to simply assume the reality

character of the self-same cup. In a similar way, phenomenology seeks to investigate

various noetic and noematic phenomena which unfold under the reduction.

A word must be said here about methodology. Husserl was uncompromising about the

special or unique character of phenomenological investigations. Because phenomenology

wishes to study the foundations of the natural attitude, it cannot use methods in its

research which are based upon the natural attitude. Over and above developing a rigorous

phenomenological method, phenomenology needs also, necessarily, to develop a new

language, since it is mapping out entirely new territory. Phenomenology may need to

borrow language from the natural attitude, but it must be sure to formulate its own

pehnomenological meanings for these terms. Husserl states in Ideas I Moreover, we may

make this quite general remark, that in the beginnings of phenomenology all concepts or

terms must in a certain sense remain fluid, always prepared to refine upon their previous

meanings in sympathy with the progress made in the analysis of consciousness and the

knowledge of new phenomenological stratifications, and to recognize in what at first to our

best insight appeared an undifferentiated unity (Husserl, 1962, p. 224). Thus phenomenology proposes an open ended project. As phenomenologists we must be willing to be

surprised at what we may find, and be open to further penetrations into the nature of our

findings. So, given this proviso, how specifically do we carry out our research? We use a

technique developed by Husserl called imaginary uariarion in order to arrive at essences

of phenomena. We use reflection, under the reduction, to discover (not invent or construct) the meaning of phenomena as they present themselves to consciousness.

IMAGINARY VARIATION

What is an essence? Briefly, an essence is what makes a thing what it is and not some

other thing. Imaginary variation is a way of asking through reflective imagination what

would I have to vary (alter) about this thing in order that it would cease to be what it is?

Husserls perceptual example of color may help to clarify what imaginary vanation is. We

ask ourselves, can we imagine color extended in space over 10 m2? Yes we can. Can we

imagine color extended in space over 10 cm2? Yes we can. Can we imagine color without

extension? No, we cannot. So, we see that an essential aspect of color is that it must be

extended in space. Our method of arriving at essences is to vary the parameters of a

phenomenon in our imagination until we arrive at the limit case. What the reader may have

noticed at this point is the subjective nature of this process. It is true that imaginary

variation is based upon individuals intutions. However, Husserl claimed that the grasping

of essences is an immediate grasping (intution) which is grasped with a certitude which lies

beyond individual idiosyncrasies. Were someone to say to Husserl I can imagine a color

without extension in space Husserl would reply that either this person is denying his own

experience of color, or he has simply not understood what extension and space

mean. It must be stated here that essences are not inferred or deduced, they are spontaneous affirmations which partake of experiential certitude. Husserl is always speaking of the

way phenomena appear to consciousness-as-such. He is likewise speaking of essences

which are graspable by any consciousness. We shall see later on that this is the place

where phenomenological psychology must deviate from Husserls philosophical transcen-

53

54

J . Bullington and G . Karlsson

S a n d J Psycho1 25 (1984)

dental phenomenology. But for now, suflice to say that all essences are grasped under the

reduction by means of imaginary variation and are direct, intuitive affirmations.

PHENOMENOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY VS. TRADITIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

Before we go into the method and subject matter of phenomenological psychology, we

would like to briefly contrast phenomenological psychology with traditional psychology.

By traditional psychology we refer to the experimental tradition in psychology dating

from W. Wundt. Wundts aspiration in seeking to establish psychology as a natural science

remains even today in contemporary psychologys scientific ideals. Such ideals are

reflected in the so called objective method which psychology adopted from the natural

sciences. Due to the successes made in physics and chemistry, psychology believed that

by adopting their quantitative method, psychology could establish its credibility in the

academic community. The natural scientific project was to explain phenomena in terms of

causal laws. Consequently, traditional psychologys guiding principle was also to explain

psychic phenomena following the principles laid out by the natural sciences. A phenomenon w a s thought to be relevant to the study of psychology only if it could be measured

and tested in some way by these natural scientific means. The contrived laboratory

conditions which became synonymous with psychological research had less and less in

common with everyday, lived experiences of human subjects. In this way the bias of a

methodology came to eclipse the psychologists interest in phenomena which were inaccessible through this method, such as the study of consciousness and subjectivity. The

psychologist as a natural scientist seeks to discover or invent abstract, explanatory causal

connections between events to account for psychological phenomena. The human being is

observed as a thing among other things, disregarding the unique psychological status of the

human being. Such physicalistic models move away from concrete subjective experiences

into abstract, derived formulas, which are often unrecognizable in the subjects naive

experience (Giorgi, 1970~).

Phenomenological psychology takes its approach from philosophical phenomenology. In

adopting Husserls to the things themselves, phenomenological psychology seeks to

develop a rigorous scientific method which would enable the researcher to thematize or

make explicit the immediate lived experience of a phenomenon, as it is lived, without

resorting to ad hoc, superimposed theories about phenomena. Such an aim brought about

a qualitative, descriptive method. This method uses: (1) subjects naive, spontaneous

descriptions of phenomena, (2) the psychological phenomenological analysis of the data

and (3) the community of researchers as a collaborative pool. Comparable to the verification of results in the quantitative approach, we find in the qualitative phenomenological

method, the phenomenological criterion of spontaneous, intuitive assent upon reading the

findings of a phenomenological study. Researchers present their findings to each other, to

the community, and sometimes to the subjects themselves. The problem of subjective

bias does not arise for phenomenological psychology in its traditional formulation, since

phenomenology recognizes the subjectivity of the researcher as the very access to the

meanings and themes which constitute the qualitative, descriptive findings. However, the

phenomenological psychological researcher should always be on guard against natural

attitude presuppositions which may not have been properly thematized and bracketed by

the researchers reduction. The criteria for a piece of phenomenological psychological

research are: ( a ) fidelity to the phenomena and (b) a rigorous phenomenological reduction.

Thus, phenomenological psychology as a human science (as opposed to a natural

science) takes fidelity to the phenomenon as it is lived as its guiding principle in the

formulation of a method. Phenomenological psychologys approach does not equate being

Scand J Psych01 25 (1984)

Phenomenological psychology

scientific with being naturally scientific. Rather than necessarily transforming meanings into quantitative expressions, as natural science does, phenomenological psychology

seeks to affirm and elucidate the pre-reflectively lived world. Given that the researcher has

followed these directives, what is the nature of phenomenological psychologys data? It is

the meaningful, descriptive expression of the subject which will provide the researcher

with the themes and generalities concerning lived phenomena.

Phenomenological psychology, true to its phenomenological origins, sees the world as

already replete with meanings. These meanings are lived everyday, yet may remain

implicit and unthematized. Phenomenological psychological research seeks to make explicit and thematic these unreflectively lived meanings. Even in traditional psychological

research we may see how these lived meanings are operating; for example, when the

researcher sets up an experiment, decides to investigate this or that phenomenon, change

this or that variable etc. Such an eidetic (essential) understanding must be present in any

researcher, for how else would he have any direction to his research? Such meanings and

eidetic understandings are not explicitely acknowledged in traditional psychological research. The traditional researcher in psychology is himself using intuitions and eidetic

understandings without the rigor of the phenomenological reduction.

The phenomenological psychologist does not concern himself unduly with facts

because he chooses to stay at the level of meaning. His emphasis is always upon the

meaning-for-subject of a phenomenon, whether that phenomenon happened once or one

hundred times, at home, or at work etc. In reading 10 descriptions (protocols) from

different subjects on anxiety, for example, the researcher will undoubtedly find a variety

of situations in which anxiety occurred. However, he will also find a common theme or

structure of the meaning of anxiety which will arise from the analysis of these different

protocols. For example, although he may find that anxiety was experienced at school, at

work or on a vacation, he does not necessarily imbue these facts with psychological

meaning. What may emerge from the study as important, could be, for example, that in all

these situations the subjects were experiencing an insecurity about their capability to do

something that mattered to them. As phenomenological psychologists we do not hypothesize beforehand about what psychological constituents or meanings we will find, but we

do allow our intutions to pick out thematically relevant material from the protocols. We

may use, just for an example, the above fictional constituent of insecurity rather than

at school at work on vacation because we intuitively grasp its thematic significance from the totality of the protocol and the synthesis of all 10 protocols. Because of the

insistence upon the priority of meaning, phenomenological psychology considers the

natural scientific accumulation of facts to be an inappropriate task for our purposes. No

matter how numerous the facts may be, no matter how sophisticated our techniques of

measuring become, facts cannot leap across the abyss into meanings. As Sartre put

it, In short, psychologists do not realize that it is just as impossible to get essence by

accumulating accidents (facts our comment) as to reach 1 by adding figures to the right of

0.99 (Sartre, 1948, p. 5).

A common misunderstanding of phenomenological psychology is to confuse it with

introspectionism (Wundt & Titchner). Briefly, the differences between introspectionism

and phenomenological psychology can be enumerated as follows:

(1) In classical introspectionism, the S is asked to observe his impressions upon

receiving certain stimuli. He is asked to reduce his impressions to the simplest elements

such as sensations, feelings, images and to locate their attributes such as intensity,

duration etc. Phenomenological psychology rules out any such assumptions about the

nature of mindconsciousness.

(2) In introspectionism, the S is asked to stick to the facts and not to include any

55

56

J. Bullington and G. Karlsson

Scand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

meanings he may associate with the stimuli, whereas phenomenological psychology is

precisely interested in the study of these meanings.

(3) The S in introspectionistic experiments had to be well trained in order to know what

kinds of self-observations were acceptable to the researcher. For phenomenological

purposes, the S is asked to freely report upon all his experiences pertaining to the

phenomenon in question and uncensored descriptions from subjects are the raw data for

phenomenological psychology.

Another school of psychology which is often associated with phenomenological psychology is gestalt psychology. Although there are similarities between the two, the relationship is a complex one, and there is no real agreement among phenomenologists about

gestalt psychologys relationship to phenomenology. It is beyond the scope of this paper to

describe the differences here in detail. However, a few words may be said about the main

difference between the two approaches. While gestalt psychology does place an emphasis

upon wholes-as-given (as opposed to the traditional atomistic psychology), gestalt psychology maintains the superiority and priority of physicalistic causes of psychological experiences. They remain in a natural attitude insofar as they embrace objectivistic theories

about phenomenon (See Merleau-Ponty, 1963).

PHENOMENOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGYS METHOD

At this point we would like to demonstrate the specific method used in a phenomenological

psychological undertaking. Although Husserl himself worked mainly with phenomenological transcendental philosophy, he did allow that a phenomenological psychology running

parallel to his philosophy was possible. The difference between phenomenological philosophy and phenomenological psychology has to do with the two different bracketings or

reductions. Under the philosophical or transcendental reduction, both the object pole

(world) and the subject pole (consciousness) are derealized or bracketed. This enabled

Husserl to study consciousness-as-such; not any particular consciousness, but the structures necessary and sufficient for any consciousness. What remains after the transcendental reduction is the transcendental ego. This is the positing ego; that is, the ego which

constitutes both the world and the mundane, situated ego. For example, in the phrase I

am aware of myself winning a game ofchess. Husserldistinguishes between two different

egos. I refers to the transcendental ego, while the second ego, myself, is the

psychological, mundane ego which is situated in the world. This psychological ego is

perspectival and present to consciousness in and through its appearances, just like any

other mundane object. There is a debate within the phenomenological movement about the

possibility and validity of a transcendental, purely reflective ego which lies outside both

the world and the psychological ego. Our main interest as psychologists, however, is the

second ego, the mundane, psychologically situated ego. This is the ego which remembers,

desires, has wishes and fears etc. In the case of the psychological phenomenological

bracketing, we bracket the object pole (we put its reality status into suspension), but we

leave the psychological ego exactly as it is in the world. We do not suspend its particularities because this is what we wish to study. We are interested in this situated ego which has

desires and fears. The psychological phenomenological reduction takes us out of the

natural attitude by subsuming the object under subjectivity (object-as-meant) and leaves us

with a situated consciousness intending meanings. From Husserls standpoint (which

claims the validity of a transcendental ego), we as phenomenological psychologists must

admit the following paradox: The I which we study (the myself ) which constitutes

the world is also itself situated in the world. It is both constiuting and constituted. We find

no difficulty in accepting this premise because our interests are not philosophical. For our

Scand J Psycho1 25 11984)

Phenomenological psychology

purposes, we need only to discover the meanings which are intended by the situated ego in

their psychological significations.

A common confusion about the phenomenological method concerns the researchers

use of intuitions to arrive at a theoretically unbiased understanding of the data (textprotoc d ) . How is a theoretically unbiased understanding possible? In order to understand

such a notion, we must first become clear about what a theory is. According to FQlesdal

and Walloe, a theory is a set of propositions whose inter relatedness is made explicit. It is

therefore characteristic of a theory that it makes clear how the different propositions

which are included in it depend upon each other (F#llesdal & Wall0e, 1977, p. 53, our

translation from Norwegian). The theory becomes the basis upon which the data is

analyzed. What is important here is that the final comprehension of the data on the part of

the researcher is dependent upon these previously formulated propositions. As phenomenological psychologists, we maintain that we d o not make any use of theories in our

understanding of the data. This does not mean, of course, that the researcher confronts his

data as a blank; we are not unbiased in the sense that we can transcend language and

culture. But to be in a culture and partake of its common preunderstandings and meaningful expressions is not the same thing as to assert and attempt to prove constructed models

or theories. For example, take the experience of reading a novel. If one reflects upon ones

own experience, we think everyone would agree that the understanding of what one has

read does not depend upon theories (in the above defined sense) about what one has

read. Rather, the reader of the text already shares a common world with the author which

enables him to grasp the meaning of the text. To say that the reader has understood

what he has read is to assume the possibility of expressing and grasping meanings through

the medium of a shared culture and language.

We have chosen to call the researchers grasping of meaning in the subjects descriptions intuition sticking to the language of Husserl (1962). However, our intuition is

not Husserls intuition of grasping essences (transcendental philosophy), but is grounded

in language and culture and is therefore an intuition of a hermeneutical kind. (See Ricoeur

1981, Titelman 1979.)

At this point we shall address the question; what kind of results do we come up with in

our research? Whereas Husserl discovered essences, phenomenological psychology discovers psychological signif cations (generalities). These psychological significations or

meaning constituents are the themes which emerge as the structure of a lived psychological phenomenon. A structure understood phenomenologically is that common

thread which runs through unique manifestations of the same phenomenon. A meaning

constituent discovered in a protocol analysis of a psychological phenomenon would be a

part of the phenomenon in interaction with other parts or constituents which in turn

make up the phenomenon in question. It is thus not the case that the phenomenological

psychologist merely points out disjointed, unrelated significations, but rather, he seeks to

discover the way in which parts or constituents of a protocol relate to one another in a

gestalt. This gestalt we call a general structure. It may also turn out that we find two or

more gestalts which we call typologies of the same phenomenon. We will demonstrate

in practice how our analyses proceed. The following method was developed by Amedeo

Giorgi at Duquesne University (see Ciorgi, 19706, 1975, Wertz, in press).

EXAMPLE O F T H E PHENOMENOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGICAL METHOD

The raw data for our studies consist of reports (descriptions) given by subjects of their

experiences of a given phenomenon. The format of such descriptions can be gathered as

retrospective protocols (running narrative), interviews, or think-aloud protocols. In this

57

58

J . Bullington and G. Karlsson

Scand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

paper we will address retrospective protocol analysis, although the method of analysis

applies to any type of text. Phenomenological psychology does not exclude the laboratory

set up per se, but the laboratory situation would be used in a phenomenological way:

namely, the subjects own description of his experience while going through the experiment would constitute our data. For purposes of clarity, we will from now on describe our

method as it applies to a retrospective protocol obtained from one subject.

After having decided what we wish to investigate, we approach subjects with the

following instructions: Describe a situation in which you felt . . . (in this case lonely).

Describe the situation, how you felt and what you did in as much detail as possible.

Include all details which come to your mind. Describe it in as much detail so that someone

who has never had the experience would understand it after your description. A good

protocol is one which is free from psychological jargon or other privileged disciplinary

biases. Such a protocol would be a spontaneous recounting of lived experience, rather

than a self-reflective, explanatory account. We present the following loneliness protocol

and thereafter the following analysis which will be used in our discussion to illustrate the

method.

This situation happened to me sometime in the recent past, and the circumstances surrounding it were

that the person I was living with had moved back to New York, and he told me that he was going to

call me at I I .OO on this particular Sunday night to let me know what had happened with him in New

York. 1 myself had been out of town and had come back earlier on this particular Sunday. Upon my

arrival I discovered that my landlord was putting in a heating unit, and the apartment w a s torn apart,

it was cold. 1 looked around and saw all his things laying around the apartment. just exactly where he

had left them. I didnt feel at home in the apartment. I felt very uprooted. Without him, I didnt feel

like I belonged here. I tried to read earlier in the evening, but I couldnt concentrate. 1 kept looking at

the clock anticipating his phone call. He didnt call at I 1 . 0 0 . I tried to continue to read. He didnt call

at 11.15, at 11-30 or at 11.45. By 12.00 1 was getting upset, and by 12.15 I felt just horrible. This was a

very crucial phone call for our relationship. I hadnt had any contact with him since he left for New

York a week ago or so. By this time in the evening 1 was afraid that he didnt care about me, this one

person whom Id been devoting myself to, at the cost of all others, didnt care about me. I looked

around the room, and I thought about living alone here in Y . and 1 thought. I havent got a friend

in the world. I tried to think of my friends, I thought, there are people other than this person who

know you. you have friends, you have a family. But at that moment they didnt seem real to me. I

couldnt shake the feeling that I was hopelessly alone. For a while I considered calling his grandmother in New York,in case something terrible had happened to him. But since it was past midnight and I

figured it was too late to call, I gave up the idea. And besides I still thought he would call. I paced

through the apartment, wringing my hands and feeling very physically agitated. He finally called me at

1.00 at night. I felt furious a t him, but after we talked some I felt calmed down and at home with

myself again.

...

We divide our analysis of the protocol into 5 steps for pedagogical purposes. Different

researchers may vary the method by a step or two, but in essence the phenomenological

psychological analysis contains the following 5 steps.

Step I

Our first step is to perform the phenomenological reduction. For our purposes, as

psychologists, we wish to read the text with an open, theoretically unbiased attitude.

However, we must maintain a psychological focus of interest as we read. (We do not, for

example, read this protocol on loneliness as a sociological text.) We read the text through,

as many times as necessary in order to get a grasp of the whole text in light of the

particular phenomenon we are investigating. We proceed from initial readings to a more

systematic reading where we focus upon discriminating the meaning units that emerge

from the text. Breaking up the text into meaning units constitutes step 2.

Scand 3 Psycho1 25 (1984)

Phenomenological psychology

Step 2

Meaning unit discriminations are divisions of the entire running text into discrete units of

meaning each of which can stand on its own as expressing relevant meaning. We have a

sense already of what is relevant by having read the text a number of times. We mark

these meaning unit divisions directly on the description in those places where we sense a

shift in the meaning in the expression of the subject, or a transformation of the situation.

Consider the following excerpt from our loneliness protocol as an example of a naturally

occurring break in meaning:

I myself had been out of town and had come back earlier on this particular Sunday. Upon my arrival, 1

discovered that my landlord was putting in a heating unit, and the apartment w a s tom apart, it was

cold.() I looked around and saw all his things laying around the apartment, just excactly as he had

left them.(5)

We divided the meaning unit as we did because the first two sentences, although they

contain several ideas, both express one psychological meaning, which we could summarize as the subjects relation to the state of the apartment (4). The last sentence contains a

new psychological meaning, namely, the introduction of the absent other into the cold,

disarranged apartment (5). We do not interpret these breaks in meaning, we do not

impose them, but we do allow our intuitions to guide our understanding of the shifts in

meaning which spontaneously emerge upon reading the protocol.

Step 3

Step number three is the transformation of these meaning units from the language of the

subject into the researchers language, which focuses upon the significations expressed in

relation to the phenomenon under investigation. Here a word must be said about the

language we use as phenomenological researchers. As has been hinted at, phenomenology

started out without having any read-made language. This pertains to phenomenological

psychology as well. The language that we use as researchers, first of all, reflects the

understanding of the whole protocol. Thus we can let the understanding of the entire

protocol influence the transformations of a particular meaning unit. There are no laws or

rules about the use of the language, but one should, of course, be mindful not to use a

language that has vague or multiple connotations. The community to whom one addresses

the study is another factor to take into account in the choice of the researcher language. If

it is phenomenological community one is addressing, there may be certain expressions

which have a meaning for them, but not for another audience, and vice versa. The use of

an expert language can often be dangerous. For instance, the expression neurotic

compulsion is obviously theoretically loaded. This is why a naive, everyday language is

preferable until we have created a bias free, descriptive vocabulary. The difficulty in

communicating our results (phenomenological structures) is cited by De Boer:

Ordinary language is completely attuned to the sphere of normal interests, i.e. to objects, and can

describe adequately only this primary objectivity. The phenomenologist must use words that are

attuned to the natural attitude. In other words, the unnatural reflective thought-stance is forced to

speak the language of the natural direction of thought. This, of course. causes certain difficulties in

communication. One condition for understanding a phenomenological analysis is that one must be

able to transpose himself into the typical phenomenological attitude .. . (1978, p. 130).

As we transform the language of the subject into the researchers language, we d o not seek

to make the subjects expressions conform to any prior hypothesized psychological

constructs. By remaining open to the description, we allow ourselves to be surprised by

whatever constituents we may find in a protocol. Our transformations into the language of

the researcher is necessary to our project because the descriptions of the subjects lived

59

60

J . Bullington and G . Karlsson

Scand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

experiences are not primarily psychological (nor primarily sociological, biological etc.). It

is the project of phenomenological psychology to tease out the psychological meanings.

We must go beyond phenomenal level (what is directly lived) to the phenomenological

level (in our example, the psychological logos of loneliness). The subjects descriptions are

phenomenal in that they describe what is directly and unreflectively lived. The phenomenological move is that reflective stance taken under the reduction which uses phenomenal

descriptions in order to arrive at a structural understanding of experience; the logos of

phenomena. We present only the first five meaning unit transformations here for reasons

of brevity.

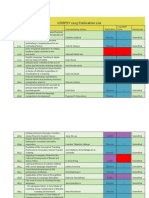

Constituents present in description

1. This situation happened to S in the recent

past.

2. S states that the person she was living with

moved back to New York.

3. The other had made plans with S to call her

on a particular day at a particular time to tell

S what had happened with him in New York.

4. S herself had been out of town and amved at

the apt. on the day of the phone call. S discovered that the apt. was tom apart by landlord repairs. It was cold.

5 . S looked around the apt. and saw all of this

persons things laying around, just exactly

where he had left them.

Constituents of description expressed in

terms revelatory of loneliness

1 . ............................................................

2. S stated that the circumstances of this occasion of loneliness centered around the absence of a significant other with whom S had

been living. This other left the S and moved

back to where he he had been living sometime

prior to living with S.

3. S and the other had made plans (a pledge or

promise) that the other would call S on the

phone at a particular time on a particular

night. S expected to find out from this phone

call what had happened 10 the other since

they last saw each other.

4. S came back from out of town to this apt.

where she and the other had lived together,

on the day of the phone call. Upon amval S

found the apt. in an unexpected state of disarray due to repairs being performed in her

absence.

5. S furthermore experienced the apt. as reminding her of the absent other.

We keep the subjects language (slightly modified, I changed to subject etc.) on the

left hand side and put our transformations directly opposite on the right, to ensure that we

do not lose sight of the subjects original expressions.

We use descriptions of experiences as access into the structure of phenomena, which by

definition must be a more narrow, abstract description. It must be remembered that the

only framework the phenomenological psychologist uses in making his transformations is

to trace out the implicit (or in some cases, explicit) meanings which he finds in the

protocol(s) themselves. The researcher makes no use of theoretical models because they

merely hinder his discovering what the protocol has to offer. Psychological sensitivity on

the part of the researcher is used to elucidate rather than define the phenomenon being

investigated. For example, we take the subjects language here: I looked around and saw

all his things laying around the apartment, just exactly where he had left them and

transform it into: S furthermore experienced the apartment as reminding her of the

absent other. We include the word furthermore here because in the overall context of

this protocol, this sentence follows directly a sentence about the Ss feeling disoriented

and cold in the apartment. Besides being cold and tom apart, the apartment furthermore

reminded her of the absent other. Both meaning units (4 and 5 ) taken together reveal the

Ss reaction to being in that apartment then, under those particular conditions. We arrived

at our transformation here by asking ourselves in imaginary variation, what did it mean in

the context of the entire protocol that the subject looked around and saw all his things

Scand J

Psycho1 25 (1984)

Phenomenological psychology

laying around the apartment, just exactly where he had left them? Does she mean that

this state of disarray created an extra cleaning burden for her? Such a transformation is not

substantiated in the text. Could her sentence mean that she experienced anger towards the

absent other for not cleaning up his things before he left? Possibly, but we must always

return to the language of the subject. We intuit that the phrase just exactly where he left

them does not express anger. The transformations take on their significance in relation to

the entire protocol on loneliness.

Step 4

Our next step as researchers is to synthesize our transformed meanings units into a

situated structure, which reads like a synopsis of the specific meaning constituents found

in the protocol. A structure, we recall, is a gestalt-like contexture in which the parts

(meaning constituents) relate to each other in an interdependent way. T h u s , the full

understanding of a phenomenon is not the result of a mere enumeration of constituents,

but rather, the way in which each constituent relates to each other constituent. As can be

seen below, the situated stmcture is a running text of the transformed meaning units. In

order to reach this structure, the researcher may omit or shift the transformed meaning

units in order to best express psychological significations. He may also wish to refer back

to the raw data ( S s language) at this point in order to ensure that nothing has been

overlooked. The situated structure is the analysis of Qne protocol in its specificness. In this

way we have at our disposal an easy-to-read, coherently organized text to compare with

our other protocols in the same study.

We present here the complete situated structure of the loneliness protocol we have used

as an example.

Loneliness for this subject was experienced when S returned to an apartment where she had been

living with a recently departed, significant other. The Ss experience of the apartment as being in a

state of disarray contributed to the Ss feeling that she was not at home. (This word contributed is an example of the way phenomenological psychology is sometimes forced to use everyday

language to express meaningful associations which we have no phenomenologically descriptive word

for at this time.) The perception of the others possessions still left in the apartment reminded the S of

the absence of this other. The other had made an agreement (a pledge) to call the S on a particular

night at a particular time. S experienced time, as she was in the apartment, as pointing towards the

expected phone call. This was a crucial phone call for their relationship. When the other had not

called at the appointed time nor after a certain period of waiting, S felt that this other did not

reciprocate her care and devotion. S began to imagine her future without this other. S felt herself to be

in a world without friends. S was unable to make her friends and family real. The only reality for S at

that moment was the unrealized phone call and the absent others lack of care for her. S could not

herself actively investigate why the other had failed to call her (by calling his relative) because she felt

that it was too late to call. She felt physically agitated as she waited passively for this phone call.

When the phone call finally arrived, S expressed anger towards the other, but eventually regained her

feeling of being at home with herself in the apartment.

Step 5

Our final step, then is to move from a collection of situated structures (many protocols of

the same phenomenon written by different subjects) to what we call a general structure

(see below), which incorporates those essential constituents of a phenomenon which run

across all the situated structures. However, it may turn out that we cannot collapse all our

situated structures under one general structure. In such a case we find various types of

the phenomenon which we call typologies. We prefer, in these cases, to write out

general typologies rather than attempt to force the data under one general structure. Our

criterion for making typologies rather than one general structure concerns the nature of the

specific constituent(s) in question. If those constituents differ in an essential way from the

61

62

J . Bullington and G. Karlsson

Scand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

other protocols, we would be doing violence to the spirit of phenomenology to exclude or

ignore those protocols which do not fit with the others. What we find in typologies are

varied structures of the same phenomenon which demand to be treated separately and in

their own right. It should be stated that before the researcher decides upon typologies on

the basis of one or more errant constituent(s1, he should return to the raw data to ensure

that he did not overlook those essentially different constituents in the other protocols.

Although in practice we do not move from one situated structure to a general structure,

we found it necessary to do so here for didactic reasons. Even this single protocol

analysis, however, can reveal for us a fuller understanding of what loneliness is. Our

general structure reads as follows:

Ss loneliness refers to the absence of a specific significant person. Other people are not able to

compensate for the absence of the missed person. The S feels at a loss (not at home) until contact

can be made with the absent other. S fells a detachment from the world and is not able to share her

loneliness with friends or family. S experiences that the action which is required to abate the

loneliness has to be initialed by the absent other. This passivity is justified by an internalization of

norms that makes Ss situation unchangeable, as far as the Ss sense of initiative is concerned.

Our general structure tells us that loneliness in this protocol w a s more than the factual

absence of the person whom the subject missed. We found that this one protocol expressed a psychological constituent of passivity which was lived by the subject as a

waiting. What the subject called a waiting we may term passivity because our

position as researchers allows us to step back reflectively and view her entire protocol as

an expression of loneliness. We saw how her passivity w a s manifested in her inability to

call friends and relatives, her unwillingness to actively investigate the reason for the delay

of the call, and finally, her entire temporal experience expressed a passivity in that her

present was focused upon the call which would amve in the future. We furthermore saw a

connection between the passivity constituent and what we called an internalization of

norms (phenomenally lived as the Ss justification for her continuing to wait) which was

expressed by the subject as it was too late to call the grandmother.

Hopefully this brief discussion has provided the reader with a basis for further thought

and discussion. Our results (as any other scientific results) point to further thematizations

and investigations. Even in our general structures we come up with findings which open up

a field for further reflections and research.

We would like to thank Amedeo Giorgi, Carl Lesche, William Phillips, Ola Svenson and anonymous

reviewers for discussions and valuable comments on earlier drafts. This study was supported by a

grant to Ola Svenson from the Swedish Council for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

REFERENCES

Dc Boer, T.The development of Husserls thought. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1978.

Fgllesdal, D. & Wall&, L. Argumenfasjonsteori og uitensknpsfilosofi Bergen: Universitetsforlaget,

1977.

Oiorgi, A. Psychology as a human science. New York: Harper and Row, 1970. (a)

Giorgi. A. Towards Phenomenologically based research in psychology. lournol of phenomenologicol

Psychology, 1970, I , 75-98. ( b )

Giorgi. A. An application of phenomenological method in psychology. In A Giorgi, C. Fisher & E.

Murray (Eds.), Duquesne Studies in Phenomenological Psychology, Vol. 2 . Pittsburgh: Duquesne

University Press, 197% 82-103.

Husserl. E. Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology. New York: Collier-Macmillan

Books, 1962.

Merleau-Ponty, M.The structure of behauior. Boston: Beacon Press, 1%3.

Scand J Psycho1 25 (1984)

Phenomenological psychology

Ricoeur, P. Phenomenology and hermeneutics. In G. B. Thompson (Ed.), Hermeneutics and the

human Sciences. Cambridge: cambridge University Press, 1981, 108-128.

Sartre, J . P. The emotions: Outline o f a theory. New York:. Citadel Press, 1948.

Titelman, P. Some implications of Ricoeurs conception of hermeneutics for phenomenological

psychology. In A. Giorgi, R. Knowles & D. L. Smith (Eds.), Duquesne Studies in Phenomenological Psychology, Vol. 3. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1979.

Wertz, F. J. From everyday to psychological description; Analyzing the moment of a qualitative data

analysis. Jourml of Phenomenological Psychology, 1983, 14, in Press.

63

You might also like

- Husserl's RealityDocument10 pagesHusserl's RealityBennet GubatNo ratings yet

- Outline On Phenomenologyical MethodDocument3 pagesOutline On Phenomenologyical MethodGalvez, Anya Faith Q.No ratings yet

- Mind Body Interaction GADocument19 pagesMind Body Interaction GAPsihoterapijaNo ratings yet

- WERTSCH James ROEDIGER Henry 2008 COLLECTIVE MEMORY Conceptual FoundationsDocument10 pagesWERTSCH James ROEDIGER Henry 2008 COLLECTIVE MEMORY Conceptual FoundationsBougleux Bomjardim Da Silva CarmoNo ratings yet

- The Understandings of Revenge Through Discussions With University StudentsDocument97 pagesThe Understandings of Revenge Through Discussions With University StudentsSAIKAT PAULNo ratings yet

- Neurophysiology Religious ExperienceDocument51 pagesNeurophysiology Religious ExperienceSamuel Espinosa MómoxNo ratings yet

- Book Critique On Halbwachs On Collective MemoryDocument11 pagesBook Critique On Halbwachs On Collective MemoryPatrick James Christian100% (1)

- Psychological Understanding of ReliglionDocument8 pagesPsychological Understanding of ReliglionDomenic MarbaniangNo ratings yet

- Reading List For Historical MethodsDocument6 pagesReading List For Historical MethodsLu TzeNo ratings yet

- Short Story Definition, Development and EvoluionDocument13 pagesShort Story Definition, Development and EvoluionSyed NaqeeNo ratings yet

- Semiotic Mediation in The Mathematics ClassroomDocument38 pagesSemiotic Mediation in The Mathematics ClassroomCeRoNo ratings yet

- Parse HandoutDocument2 pagesParse HandoutRea AquinoNo ratings yet

- The Lost CauseDocument25 pagesThe Lost Causebubbak51No ratings yet

- Phenomenologybyhusserl 141125025956 Conversion Gate01 PDFDocument13 pagesPhenomenologybyhusserl 141125025956 Conversion Gate01 PDFAnonymous Dq88vO7aNo ratings yet

- Husserl Presented Phenomenology With A Transcendental TurnDocument2 pagesHusserl Presented Phenomenology With A Transcendental TurnValenzuela BryanNo ratings yet

- Bullington, J - The Expression of The Psychosomatic Body From A Phenomenological Perspective - The Lived BodyDocument20 pagesBullington, J - The Expression of The Psychosomatic Body From A Phenomenological Perspective - The Lived BodyTsubasa KurayamiNo ratings yet

- Husserl's Phenomenology: Methods of PhilosophizingDocument36 pagesHusserl's Phenomenology: Methods of PhilosophizingLV MartinNo ratings yet

- IEP-Phenomenological Reduction-CoganDocument26 pagesIEP-Phenomenological Reduction-CoganAnonymous LnTsz7cpNo ratings yet

- Davis Phenomenological MethodDocument2 pagesDavis Phenomenological MethodBetül KebeliNo ratings yet

- Ideas General Introduction To Pure PhenomenologyDocument5 pagesIdeas General Introduction To Pure PhenomenologyAndré ZanollaNo ratings yet

- @HUSSERL - Encyclopaedia BritannicaDocument12 pages@HUSSERL - Encyclopaedia BritannicaGabrielHenriques100% (1)

- The Phenomenological MethodDocument9 pagesThe Phenomenological MethodChanel Co Zurc Adel0% (1)

- Husserl - Encyclopedia Britannica ArticleDocument14 pagesHusserl - Encyclopedia Britannica ArticlePhilip Reynor Jr.100% (1)

- PhenemenologyDocument8 pagesPhenemenologymt_tejaNo ratings yet

- Ahmed OrientationsDocument33 pagesAhmed OrientationsGavin LeeNo ratings yet

- 03 Phenomenology 150528024332 Lva1 App6892 PDFDocument53 pages03 Phenomenology 150528024332 Lva1 App6892 PDFAnonymous HWsv9pBUhNo ratings yet

- Orientations Toward A Queer PhenomenologyDocument33 pagesOrientations Toward A Queer PhenomenologybelbelvelvelNo ratings yet

- Mapping Territories A Phenomenology of LDocument14 pagesMapping Territories A Phenomenology of LprofesorbartolomeoNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology of HusserlDocument8 pagesPhenomenology of HusserlSaswati ChandaNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Psy From PhenomelogyDocument27 pagesThe Meaning of Psy From PhenomelogyFrancisco Mujica CoopmanNo ratings yet

- The Interpreted World (Ernesto Spinelli) Cap 1 y 2Document31 pagesThe Interpreted World (Ernesto Spinelli) Cap 1 y 2Bobollasmex86% (14)

- X 00127Document16 pagesX 00127Alessandro C. GuardascioneNo ratings yet

- Contributions To Thought: Psychology of The ImageDocument39 pagesContributions To Thought: Psychology of The ImagechaitanyashethNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive ReportDocument10 pagesComprehensive ReportAbby OjalesNo ratings yet

- NoneDocument4 pagesNonegolenatristanNo ratings yet

- Drummond - Husserl On The Ways To The Performance of The ReductionDocument23 pagesDrummond - Husserl On The Ways To The Performance of The ReductionstrelicoNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology2 - BillonesDocument4 pagesPhenomenology2 - BillonesJayzer BillonesNo ratings yet

- Methods of Philosophizing: Jenny Lou Maullon - Guansing Teacher, San Luis Senior High SchoolDocument214 pagesMethods of Philosophizing: Jenny Lou Maullon - Guansing Teacher, San Luis Senior High SchoolCathleen AndalNo ratings yet

- Edmund Husserl's Transcendental Phenomenology: by Wendell Allan A. MarinayDocument9 pagesEdmund Husserl's Transcendental Phenomenology: by Wendell Allan A. MarinaySilmi Rahma PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Alfred Schutz, Type and Eidos in HusserlDocument20 pagesAlfred Schutz, Type and Eidos in Husserllorenzen62No ratings yet

- Being in The World With Others Aron Gurwitsch PDFDocument9 pagesBeing in The World With Others Aron Gurwitsch PDFknown_unsoldierNo ratings yet

- Husserl, E. - Phenomenology (Encyclopedia Britannica) PDFDocument11 pagesHusserl, E. - Phenomenology (Encyclopedia Britannica) PDFJuan Diego Bogotá100% (1)

- "Consciousness Is Consciousness of Something": Edmund Husserl Martin HeideggerDocument2 pages"Consciousness Is Consciousness of Something": Edmund Husserl Martin HeideggerAnalyn FabianNo ratings yet

- CMCD ResearchDocument9 pagesCMCD ResearchMatthijs RuiterNo ratings yet

- Queer Phenomenology Sara AhmedDocument33 pagesQueer Phenomenology Sara AhmedGregory Gibson50% (2)

- Phenomenology TerminologyDocument8 pagesPhenomenology TerminologyfenomenologijaNo ratings yet

- Moral Phenomenology: Foundational Issues: NO9057 No of PagesDocument19 pagesMoral Phenomenology: Foundational Issues: NO9057 No of PagesErol CopeljNo ratings yet

- Ass 2Document3 pagesAss 2vioandnonaNo ratings yet

- Gmnp1y55a Existentialism-and-PhenomenologyDocument1 pageGmnp1y55a Existentialism-and-PhenomenologyAthena AshbieNo ratings yet

- Husserl and HyleDocument12 pagesHusserl and HyledeSilentioNo ratings yet

- Orientations Toward A Queer Phenomenology - Sarah AhmedDocument33 pagesOrientations Toward A Queer Phenomenology - Sarah AhmedSofia EmmeNo ratings yet

- 1 Phenomenology and Embodied CognitionDocument10 pages1 Phenomenology and Embodied CognitionKiran GorkiNo ratings yet

- Lecturas HusserlDocument2 pagesLecturas HusserlJose Luis Garcia PalaciosNo ratings yet

- An Essay On PhenomenologyDocument12 pagesAn Essay On Phenomenologybridgeindia100% (1)

- Critical Study of Husserl's Nachwort To Ideas IDocument9 pagesCritical Study of Husserl's Nachwort To Ideas IBlaise09No ratings yet

- The Phenomenological Method of Gestalt Therapy Revisiting Husserl To Discover The Essence of Gestalt Therapy 1Document16 pagesThe Phenomenological Method of Gestalt Therapy Revisiting Husserl To Discover The Essence of Gestalt Therapy 1Nina S MoraNo ratings yet

- 09 Husserl - The Encyclopaedia Britannica Article - Draft EDocument19 pages09 Husserl - The Encyclopaedia Britannica Article - Draft EAleksandra VeljkovicNo ratings yet

- More Discipline On PhenomenologyDocument9 pagesMore Discipline On PhenomenologyCarlos FegurgurNo ratings yet

- Pang Peipei About Sartre Concept of IntentionalityDocument7 pagesPang Peipei About Sartre Concept of IntentionalitydavipantuzzaNo ratings yet

- Lacan and AddictionDocument257 pagesLacan and Addictionmac100% (12)

- Umbra Aesthetics and Sublimation 1999Document86 pagesUmbra Aesthetics and Sublimation 1999macNo ratings yet

- Economies of Excess: ParallaxDocument3 pagesEconomies of Excess: ParallaxmacNo ratings yet

- Istanbulpublicationlist2015 CpsycDocument23 pagesIstanbulpublicationlist2015 CpsycmacNo ratings yet

- The Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologyDocument25 pagesThe Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologymacNo ratings yet

- AbstractBook CPSYC 2015Document58 pagesAbstractBook CPSYC 2015macNo ratings yet

- From The SAGE Social Science Collections. All Rights ReservedDocument12 pagesFrom The SAGE Social Science Collections. All Rights ReservedmacNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonmacNo ratings yet

- Alain Badiou-The Event in DeleuzeDocument8 pagesAlain Badiou-The Event in DeleuzeonesplitsintotwoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75Document28 pagesJournal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75macNo ratings yet

- Body & Society 2005 Aho 1 23Document23 pagesBody & Society 2005 Aho 1 23macNo ratings yet

- Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75Document28 pagesJournal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75macNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Today Fall 2009 53, 3 Proquest Research LibraryDocument21 pagesPhilosophy Today Fall 2009 53, 3 Proquest Research LibrarymacNo ratings yet

- J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2012 Kirshner 1223 42Document20 pagesJ Am Psychoanal Assoc 2012 Kirshner 1223 42macNo ratings yet

- Journal of The American Psychiatric Nurses Association-2006-Kutney-22-7Document6 pagesJournal of The American Psychiatric Nurses Association-2006-Kutney-22-7macNo ratings yet

- Theatre of Alain BadiouDocument12 pagesTheatre of Alain BadioumacNo ratings yet

- 22 1-2 GirouxDocument14 pages22 1-2 GirouxmacNo ratings yet

- Diagonals NorrisDocument39 pagesDiagonals NorrismacNo ratings yet

- Parrhesia12 MeillassouxDocument11 pagesParrhesia12 MeillassouxBenny Apriariska SyahraniNo ratings yet

- HallwardDocument3 pagesHallwardmacNo ratings yet

- Art:10.1007/s11841 008 0078 ZDocument14 pagesArt:10.1007/s11841 008 0078 ZmacNo ratings yet

- Zizek Avec BadiouDocument14 pagesZizek Avec BadiouJoshua BarnesNo ratings yet

- Nirenbergs Badiousnumber Complete PDFDocument32 pagesNirenbergs Badiousnumber Complete PDFRui MascarenhasNo ratings yet

- John Lippitt - Nietzsche, Zarathustra and The Status of LaughterDocument11 pagesJohn Lippitt - Nietzsche, Zarathustra and The Status of LaughterMarelin Hernández SaNo ratings yet

- Jenkins 2012 Philosophy CompassDocument10 pagesJenkins 2012 Philosophy CompassmacNo ratings yet

- Uq351611 OaDocument38 pagesUq351611 OamacNo ratings yet

- ContentDocument23 pagesContentmacNo ratings yet

- DocDocument9 pagesDocmacNo ratings yet

- Owen-2003-European Journal of PhilosophyDocument24 pagesOwen-2003-European Journal of PhilosophymacNo ratings yet

- RPL RecognitionDocument2 pagesRPL Recognitionthe_govNo ratings yet

- MBA II BRM Trimester End ExamDocument3 pagesMBA II BRM Trimester End Examnabin bk50% (2)

- Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh: Provisional Admit Card For Admission Test of Ph.D. in Clinical PsychologyDocument2 pagesAligarh Muslim University, Aligarh: Provisional Admit Card For Admission Test of Ph.D. in Clinical Psychologyalbaanamu321No ratings yet

- Youtube Channel For Computer Science - It EngineeringDocument9 pagesYoutube Channel For Computer Science - It EngineeringpriyasNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Language and EducationDocument2 pagesEncyclopedia of Language and EducationPezci AmoyNo ratings yet

- Icnd120cg PDFDocument74 pagesIcnd120cg PDFHetfield Martinez BurtonNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Management Theory PDFDocument2 pagesEvolution of Management Theory PDFAndrea0% (1)

- Criteria of A Good ResearchDocument13 pagesCriteria of A Good ResearchABBEY JEREMY GARCIANo ratings yet

- Titi Corn Is A Kind of Food Ingredient Made From Corn Raw Materials Whose Manufacturing Process Uses ToolsDocument2 pagesTiti Corn Is A Kind of Food Ingredient Made From Corn Raw Materials Whose Manufacturing Process Uses Toolsnurwasilatun silaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Compact Heat ExchangerDocument8 pagesThesis On Compact Heat Exchangerafkogsfea100% (2)

- Lab Report Evaluation Form - Revise 2 0Document5 pagesLab Report Evaluation Form - Revise 2 0markNo ratings yet

- Action PlanDocument3 pagesAction PlanROMNICK DIANZONNo ratings yet

- Good and Bad CVsDocument5 pagesGood and Bad CVsrahulkumaryadavNo ratings yet

- The Teacher's Role in Promoting Music & MovementDocument21 pagesThe Teacher's Role in Promoting Music & MovementTerry Ann75% (4)

- Pharmacy Students' Perceptions of Assessment and Its Impact OnDocument9 pagesPharmacy Students' Perceptions of Assessment and Its Impact OnCarolina MoralesNo ratings yet

- Copy ReadingDocument54 pagesCopy ReadingGienniva FulgencioNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Education PDFDocument1 pageBilingual Education PDFMaria Martinez SanchezNo ratings yet

- SDETDocument4 pagesSDETjaniNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishDocument9 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishElLa ElLaphotzx85% (13)

- Effect of Spirituality in WorkplaceDocument8 pagesEffect of Spirituality in WorkplaceLupu GabrielNo ratings yet

- Mstem Definition and ImportanceDocument1 pageMstem Definition and Importanceapi-249763433No ratings yet

- BiographyDocument6 pagesBiographyMichael John MarianoNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Eng PDFDocument2 pagesMechanical Eng PDFahmed aboud ahmedNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Day 1Document5 pagesLesson Plan Day 1api-313296159No ratings yet

- Instructions To Take LUMS SBASSE Scientific Aptitude Test - FDocument2 pagesInstructions To Take LUMS SBASSE Scientific Aptitude Test - FMohammad HaiderNo ratings yet

- Modelos Innovadores Serv SM Por No EspecialsitasDocument13 pagesModelos Innovadores Serv SM Por No EspecialsitasCESFAM Santa AnitaNo ratings yet

- OCR GCSE Computer Science EPQ Pack Sample ChapterDocument7 pagesOCR GCSE Computer Science EPQ Pack Sample Chapteromotayoomotola485No ratings yet

- NSBI Data Gathering Forms SY 2022-2023 - v3.0Document14 pagesNSBI Data Gathering Forms SY 2022-2023 - v3.0Yza Delima100% (1)

- Student Family Background QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesStudent Family Background Questionnairemae cudal83% (6)

- Techno India University, Kolkata: (B.Tech Civil Engineering)Document3 pagesTechno India University, Kolkata: (B.Tech Civil Engineering)HimanshuNo ratings yet