Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10.0000@graphics - Tx.ovid - Com@generic 97126320E0F2

Uploaded by

nanasalemOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10.0000@graphics - Tx.ovid - Com@generic 97126320E0F2

Uploaded by

nanasalemCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL PAPER

Comparison of Outcome After Mesh-Only Repair, Laparoscopic

Component Separation, and Open Component Separation

Winnie M. Y. Tong, MD,* William Hope, MD, David W. Overby, MD,

and Charles S. Hultman, MD, MBA*

Abstract: Component separation (CS) has been advocated as the technique

of choice to reconstruct complex abdominal hernia defects, especially in the

setting of gross contamination. However, open CS was reported to have

relatively high incidences of wound complications. Minimally invasive

approaches to CS were proposed by several surgeons to reduce wound

morbidity. To date, there are limited comparative data between minimally

invasive CS (MICS) versus open CS. In this article, we reviewed existing

literature on open CS versus MICS with respect to their recurrence and

complication rates. Our analysis appeared to show that MICS has comparable recurrence and complication rates relative to open CS although our

analysis had several limitations. To demonstrate the management of complications after MICS, we reported our experience of using MICS to repair

a recurrent incisional hernia in a 63-year-old man after a perforated ulcer.

STUDY AIMS

In this study, we will review the literature on open CS and

MICS to determine whether there is a benefit to perform MICS for

complex ventral hernia repair. We will also present a patient with a

recurrent, incisional hernia who underwent MICS for hernia repair

for definitive closure and describe how the postoperative complication was managed.

METHOD

We reviewed the literature on open CS and MICS, with

special attention paid to the hernia recurrence and complication

rates, to determine a better surgical option for complex ventral

hernia repair.

Key Words: component separation, ventral hernia repair, laparoscopy

Search Strategy

(Ann Plast Surg 2011;66: 551556)

Electronic databases on PubMed were searched between 2000

and 2010, and studies were identified using the words component

separation and hernia.

Selection Criteria

omplex ventral hernia repair in the presence of infection presents unique challenges for reconstruction. The use of autologous tissue to reconstruct complex defects has been advocated in the

setting of gross contamination in which prosthetic biomaterial is

contraindicated. In 1990, Ramirez et al1 first described component

separation (CS) by releasing the lateral abdominal wall myofascial

unit to achieve up to 10 cm of unilateral rectus advancement. CS

creates a dynamic repair of muscles along the midline by medialization of the rectus, thereby restoring a functional innervated

abdominal wall in a tension-free closure. Case series have documented wound complications namely seromas, subcutaneous abscess, and flap necrosis in up to 40% of cases.2 The extensive

dissection and the division of the abdominal perforators necessary to

raise large lipocutaneous flaps to access the lateral abdominal

musculature was thought to contribute to the high wound morbidity

in open CS. Recognizing the limitations of open CS, attempts have

been made to use less invasive approaches. Minimally invasive CS

(MICS) directly access the lateral abdominal wall by utilizing

balloon dissectors and laparoscopic or endoscopic visualization.

Several authors35 recently published their experience with MICS

with variable outcomes.

Studies on either open CS or MICS for ventral or incisional

hernias, which were written in the English language, were included.

Mixed studies that included other types of hernia repairs such as

open repairs with sutures alone or different prosthetic mesh were

included. We excluded studies that reported CS as part of a staged

hernia repair. The primary outcome for the review was the number

of patients who developed a recurrent incisional hernia. The secondary outcomes for the review included length of follow-up;

overall complication rate; and individual complications such as

seroma, hematoma, enterocutaneous fistula, superficial infection,

mesh infection, or dehiscence. Overall complication was defined as

any systemic or wound complications that occurred postoperatively

as reported in the study.

Data Analysis

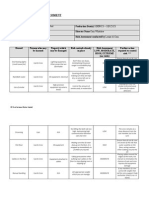

A list of studies on open CS is shown in Table 1, whereas

Table 2 shows the studies on MICS. Statistical analysis was not

performed on the data.

RESULTS

Received November 30, 2010, and accepted for publication, after revision,

December 10, 2010.

From the *Divisions of Plastic Surgery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill,

NC; Division of Gastrointestinal Surgery, New Hanover Regional Medical

Center, Wilmington, NC; and Divisions of Gastrointestinal Surgery and

Burn Surgery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Supported in part by the Ethel and James Valone Plastic Surgery Research

Endowment of the UNC Division of Plastic Surgery.

Presented at (as a poster) the 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the Southeastern

Society of Plastic Surgeons, June 2010, Palm Beach, FL.

Reprints: Winnie Mao Yiu Tong, MD, Division of Plastic Surgery, University of

North Carolina, 7040 Burnett Womack Building, CB 7195, Chapel Hill, NC

27599 7195. E-mail: wtong@unch.unc.edu.

Copyright 2011 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

ISSN: 0148-7043/11/6605-0551

DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31820b3c91

A total of 29 publications were retrieved and 6 studies were

excluded because the described operations did not involve ventral/

incisional hernia repairs with the CS technique by either the MICS

or open CS approach. Two studies were excluded because they did

not contain any outcome data. The remaining 21 publications consisted of 927 patients who underwent one of the following operations: open CS (803 patients), MICS (41 patients), mesh repair (66

patients), or suture repair (17 patients). Open CS can be further

categorized into following 2 groups: open CS alone (75 patients, 11

studies) and open CS with mesh (728 patients, 9 studies). Both

synthetic and biologic meshes were included in the open CS with

mesh group. Among the 5 studies on MICS, there was 1 comparative

study with open CS and the remaining 4 were case series. All the

case series report on MICS exclusively. The 16 studies on open CS

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

www.annalsplasticsurgery.com | 551

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

Tong et al

TABLE 1. A List of Studies on Open Component Separation (CS)

Type of Repair

No.

Patients

6

7

Fistula, NA

Recurrent hernia, NA

Open CS

Open CS bilaminar alloderm

2

16

Recurrent hernia, NA

Open CS onlay mesh

Hernia, 780 cm2

10

CS alloderm onlay/alloderm

interposition/alloderm

prolene mesh

CS

Burn patient decompressive

laparotomy, 7501000 cm2

Damage control celiotomy

CS

open abdomen, NA

CS mesh

Reference

11

Patient Characteristics,

Size of Defect

Temporary abdominal

closure, NA

12

13

Hernia, 96 cm2

Hernia, NA

14

15

545

27

6.7

Infection 25%

Wound infection 33%

Mesh infection 33%

Mesh infection 25%

Fistula 50%

Seroma 25%

Total 0%

Intraoperative 28.6%

Postoperative 66.7%

(No data on types of complications)

0%

33%

NA

Mesh

Primary closure

16

Hernia, NA

17

Open abdomen or recurrent

hernia, NA

Open CS alloderm

Alloderm

Mesh (ePTFE)

22

15

18

Open CS

19

Direct repair

Mesh

Open CS

Open CS mesh

Direct repair

Mesh

Open CS

CS dermal graft from

panniculectomy

3

5

2

9

2

5

14

2

Morbid obese, NA

None, but 7 with

laxity of alloderm

8

3

1

90

20

NA

3.5

Open CS

Open CS mesh

Renal transplant, NA

18.3%

12

16

NA

Herniated gravid uterus, NA

Morbid obese, NA

19

0%

0%

Mean

Follow-up

in Months

Death 66%

8

2

2

10

1

7

1

9

14

Contaminated wound, NA

Total 50%

Seroma 12%

Superficial dehiscence 6%

Hematoma 0.08%

Seroma 5%

Infected mesh 1.8%

Enterocutaneous fistula 1%

Total 22.2%

Hernia

Recurrence

Rate

CS

CS mesh

CS tissue transfer

Mesh

Mesh tissue transfer

Primary closure

CS

Mesh

Open CS

18

Complications

(Complication Rate)

Total 100%

Total 30%

Seroma 22%

Wound infection 9%

Total 0%

Wound dehiscence 9%

Deep infection 10%

Mesh erosion 1%

Hematoma 1%

Seroma 3%

Death, MI 1%

NA

NA

Total 72%

Wound infection 10%

Skin necrosis 5%

Hematoma 5%

Mesh removal 35%

Total 52%

Wound infection 16%

Skin necrosis 11%

Hematoma 5%

Seroma 21%

Total 47%

0%

0%

Total 14%

Total 100%

Abscess 50%

Wound infection 50%

0%

0%

25%

50%

50%

40%

0%

43%

0%

22%

7%

0%

5.5%

13%

60%

22%

NA

NA

56

12

50

22.2

36

52%

0%

40%

0%

0%

50%

0%

21%

0%

14

26

16

ePTFE indicates expanded polytetrafluoroethylene; NA, not available; MI, myocardial infarction.

552 | www.annalsplasticsurgery.com

2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

Comparison of Outcome

TABLE 2. A List of Studies on Minimally Invasive Component Separation (MICS)

Patient Characteristics,

Size of Defect

22

3

Hernia 382 cm2

416 cm2

Obese stoma, 367 cm2

Hernia, 306 cm2

23

Hernia

Recurrence

Rate

Mean

Follow-up in

Months

Type of Repair

No.

Patients

Complications

(Complication Rate)

MICS

Open

Pannieculectomy MICS

MICS laparoscopic hernia repair

22

22

3

4

27%

32%

0%

0%

41.5

1

Recurrent hernia, NA

MICS mesh (FlexHD, Surgisis)

20%

Infected mesh, 338 cm2

MICS

Cadaver, NA

24

Porcine, NA

Laparoscopic release of transverses

abdominus and posterior sheath

MICS Open CS

Total 27%

Total 52%

Total 0%

Total 50%

Seroma 50%

Total 40%

Abscess 20%

Hematoma 20%

Total 43%

Wound infection 14%

Hematoma 14%

NA

NA

Reference

21

10

5

15

0%

4.5

NA

NA

NA

NA

CS indicates component separation; NA, not available.

Complications

TABLE 3. Comparison of Open CS, MICS, Mesh Repair,

and Suture Repair for Hernia

Open CS Open Open

(With and CS

CS

Without With Without

Mesh Suture

Mesh)

Mesh Mesh MICS Repair Repair

Mean follow-up

in months

Hernia recurrence

rate

Total complication

rate

Seroma rate

29.3

33

27

12.6

31

18.8

21%

16.7%

27%

17%

33%

24%

35%

21%

59%

32%

56%

NA

NA

NA

0%

0%

5.1%

4.8%

CS indicates component separation; MICS, minimally invasive component separation; NA, not available.

included 1 randomized controlled study and 15 retrospective studies.

Among these 15 retrospective studies on open CS, comparative data

were available for other types of hernia repair in 6 studies. There

were 7 studies on mesh repair and 4 on suture repair. Results are

summarized in Table 3.

Length of Follow-up

The average length of follow-up was 29.3 months for open

CS, 12.6 months for MICS, 31 months for mesh repair, and 18.8

months for suture repair. When open CS was further categorized into

open CS with mesh and open CS alone, the average length of

follow-up was 33 months and 27 months, respectively. Data were

available on length of follow-up in 12 studies (75%) for open CS, 5

studies (100%) for MICS, 5 studies (71%) for mesh repair, and 2

studies (50%) for suture repair.

Overall complication rates were as follows: 56% for mesh

repair, 35% for open CS, and 32% for MICS. There were insufficient

data to determine the complication rate on suture repair alone. Data

were available on overall complications in 11 studies (91%) for open

CS, 5 studies (100%) for MICS, 2 studies (28%) for mesh repair, and

2 studies (50%) for suture repair. The rate of seroma among the

groups was 5.1%, 4.8%, 0%, and 0% for open CS, MICS, mesh

repair, and suture repair, respectively. There were 2 hematomas in

open CS and 1 hematoma in mesh repair. There were 6 cases of

enterocutaneous fistulas in open CS. There was 1 dehiscence in open

CS. There were 17 superficial infections and 21 mesh infections in

open CS. There were 8 mesh infections with mesh repair and 8

wound infections in laparoscopic CS.

Minimally Invasive CS Versus Open CS

A comparison between MICS and open CS showed comparable hernia recurrence rates between the 2 groups (MICS 17%;

open 21%). Overall complications were also similar in MICS

(32%) and open CS (35%).

CS Versus Mesh Repair

When hernia recurrence rates were compared between the

open CS method and the mesh repair method, the open CS rate

(21%) appeared to fare better than mesh repair rate (33%). Similarly,

the recurrence rate for endoscopic CS (17%) appeared to be lower

than that of the mesh repair (33%). Comparative data on complications for open CS and mesh repair were limited to a single randomized study that showed comparable complication rate between the 2

groups.

Hernia Recurrence

Open CS Alone Versus Open CS With Mesh

Hernia recurrence was as follows: 21%, 17%, 33%, and 24%

for open CS, MICS, mesh repair, and suture repair, respectively.

Open CS with mesh seemed to have lower recurrence rate than open

CS alone (16.7% vs. 27%, respectively). Data on hernia recurrence

were reported in all studies on MICS, mesh repair, and suture repair,

whereas 91% of the studies reported on open CS documented hernia

recurrence rate.

Open CS was further divided into following 2 groups: open

CS with mesh and open CS alone. Patients who had open CS with

mesh appeared to do better than those who had open CS alone.

Fewer hernia recurrence (with mesh: 16.7% vs. without mesh: 27%)

and overall complication (with mesh: 21% vs. without mesh: 59%)

appeared to be seen in open CS with mesh compared with open CS

alone.

2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

www.annalsplasticsurgery.com | 553

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

Tong et al

Suture Repair

Hernia recurrence rate was 24% for suture repair. There were

insufficient data to determine the complication rate after suture

repair of hernia.

Overall, the data collected from the literature review appeared

to indicate that the complication rate was comparable between open

CS and MICS. To highlight the management of postoperative

complication after repair of a recurrent ventral hernia by MICS

approach, the following case study is presented.

CASE STUDY

A 63-year-old man with a history of multiple abdominal

surgeries presented to clinic with an incisional hernia in need of

definitive abdominal closure. His medical history started approximately 1 year before presenting to us with a perforated duodenal

ulcer that was repaired with an omental patch, but the abdominal

wound dehisced. He was taken to the operating room for placement

of a jejunostomy tube and bridging abdominal closure with an

acellular human dermis (FlexHD, Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, Edison, NJ). The bridging repair failed as the human acellular dermis tore away from the fascia leaving the patient with an

open abdomen. Subsequently, he underwent a split-thickness skin

graft over the open abdominal wound. However, an enterocutaneous

fistula developed through the skin graft at his old jejunostomy tube

site (Fig. 1). Ultimately, when the nutritional and functional status of

the patient improved, the enterocutaneous fistula was taken down

and the abdominal wound was closed primarily.

When we examined the patient on the preoperative visit prior

to his MICS operation, the patient was afebrile, normotensive, and

in sinus rhythm. Examination of the abdomen showed a closed

abdomen with necrotic skin edges (Fig. 2). There was a loss of

domain. The abdomen was soft, nontender without guarding, or

rigid. Laboratory studies were normal.

We performed definitive closure of the 30 15 cm hernia

defect (Fig. 3) using a combination of MICS and Rives-Stoppa

repair with synthetic mesh. This was accomplished by making an

incision below the costal margin lateral to the rectus abdominus

muscle to expose the external oblique aponeurosis. After the potential space was created between the external and internal oblique with

a laparoscopic inguinal hernia balloon dissector, the external oblique

was incised longitudinally using coagulating scissors (Fig. 4). The

FIGURE 2. The enterocutaneous fistula was taken down and

the abdominal wall was closed but patient developed skin

flap necrosis.

FIGURE 3. The necrotic skin flap was debrided and the hernia defect measured 30 15 cm.

external oblique was incised superior to the costal margin to the

inguinal ligament on the side contralateral to the gastrostomy tube.

The Rives-Stoppa method was used to repair the ventral hernia with

a coated polypropylene mesh (Proceed, Ethicon, Inc., Sommerville,

NJ). Blood loss was estimated to be 100 mL. He was discharged on

postoperative day 16. He had a small area of wound dehiscence with

mesh exposed at a clinic visit 2 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 5). With

dressing changes, the open wound eventually closed without a mesh

infection. At 13-month follow-up, there was no hernia recurrence

and the patients wound has healed (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

FIGURE 1. A 61-year-old man with a recurrent incisional hernia that was covered with a skin graft. He developed an enterocutaneous fistula (black solid arrowhead) through the

skin graft.

554 | www.annalsplasticsurgery.com

Complex ventral hernia repair, in the setting of loss of domain

and unstable coverage as demonstrated in the case we presented,

remains a difficult problem for many reconstructive surgeons. As

described by Ramirez et al,1 CS provides a viable option in such

2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

Comparison of Outcome

FIGURE 6. Wound was healed at 13-months follow-up.

FIGURE 4. An incision was made lateral to the rectus abdominus muscle to expose the external oblique aponeurosis

(not shown). The external oblique was incised from superior

to the costal margin to the inguinal ligament using coagulating scissors to facilitate fascial closure without creation of

skin flaps. A Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair is performed with mesh placed in the retromuscular position (not

shown).

FIGURE 5. Mesh was exposed requiring dressing changes.

situation by using autologous tissue to recreate a functional dynamic

abdominal wall. However, earlier studies of open CS showed a

relatively high wound complication rate.2 In an attempt to reduce

wound complications, which were felt to be due to the extensive

dissection, required to raise the lipocutaneous flaps in open CS, a

minimally invasive approach to CS has been advocated.35 To date,

there is still a paucity of comparative data between open CS and

MICS. This study reports the most current review of the existing

literature on the 2 procedures.

Our literature review did not appear to show that MICS

reduce wound morbidity when compared with open CS. The only

direct comparative study evaluating MICS to open CS was recently

2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

published by Harth and Rosen21 and reported a trend toward lower

wound complications in MICS relative to open CS (27% vs. 52%,

respectively), although there was no statistical significance. Since

MICS is a relatively novel technique and our analysis included all

existing studies, it is conceivable that some data included in our

analysis may be a reflection of the learning curve of the surgeons.

Therefore, our reported complication rate for MICS may be higher

than the true value. Learning curves have been reported in other

minimally invasive procedures. For example, Suter et al25 performed their initial 100 cases of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric

bypass and reported a complication rate of 25% in their first 70

patients versus 2.7% in the last 30 patients. Assuming data from

other minimally invasive studies is applicable to MICS, the complication rate in MICS may decrease as the surgeon experience increases. If more long-term data are available on MICS, we may be

able to see a benefit from this less invasive approach over open CS.

Existing data, albeit limited, showed that the long-term outcome of MICS is comparable to open CS. The single comparative

study21 on MICS and open CS showed a similar hernia recurrence

rate between the 2 groups (32% in open CS vs. 27% in MICS; P

0.99). The mean follow-up periods for the open and minimally

invasive groups in that study were similar (16 vs. 14 months,

respectively; P 0.65). These findings are supportive of our results

that demonstrated hernia recurrence rates to be comparable between

MICS and open CS. Long-term prospective studies are needed to

resolve this issue.

Preliminary data appeared to indicate that patients undergoing

CS for complex hernia repair would benefit from reinforcement with

prosthetic material.26 Our study seemed to suggest a benefit in

outcome from open CS with mesh relative to open CS alone.

Patients who had open CS alone had higher hernia recurrence and

complication rates than those who had open CS with mesh. A

retrospective study by Espinosa-de-los-Monteros et al26 also

showed a significantly lower recurrence rate when CS was

reinforced with biologic repair material (0%) relative to CS alone

(13%; P 0.006). Again, long-term prospective studies are

needed to resolve this issue.

How CS compares to mesh repair in complex hernia cases is

controversial. Admittedly, this study was not designed to compare

CS with mesh repair, and we did not include all published studies on

mesh repair in this review. However, preliminary analysis from our

study proposed a trend toward lower hernia recurrence in either open

or MICS when compared with open mesh repair. The use of

autologous tissue to restore a functional innervated abdominal wall

in a tension-free closure in CS by minimally invasive or open

approach may improve the long-term durability of the hernia repair.

www.annalsplasticsurgery.com | 555

Annals of Plastic Surgery Volume 66, Number 5, May 2011

Tong et al

On the other hand, de Vries Reilingh et al conducted a randomized

study comparing the use of open CS with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh to reconstruct giant midline abdominal

wall hernia. The study was terminated early because of an unacceptably high frequency of wound complications resulting in subsequent prosthetic loss in the ePTFE group. Although their

interim analysis showed that hernia recurrence was higher in the

CS versus ePTFE group, they concluded that CS is better than

mesh repair for complex hernia cases because of the lower

associated wound complications.17

There are several limitations in our study. Our analysis

aggregates disparate methods and is limited by the quality of the

included studies. Very few studies selected for this analysis are

comparative trials of techniques or randomized controlled trials.

Almost all the studies selected for this report are limited by small

sample size, variable patient population, lack of a control group,

short follow-up, nonstandardized operative technique, and variable

outcome measures. Our data were only limited to those studies that

performed MICS and did not include all existing data on other

methods of hernia repairs. MICS as discussed earlier is still an

evolving technique, and the data may be biased by the learning curve

of the reporting surgeons.

CONCLUSION

Based on mostly retrospective data from uncontrolled studies,

this review demonstrates that complication and hernia recurrence

rates appear to be comparable between open CS and MICS. More

comparative studies on the various surgical options for complex

hernia repair will be important to delineate the optimal solution to

this complex problem.

REFERENCES

1. Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL. Components separation method for

closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 1990;83:519 526.

2. Joels CS, Vanderveer AS, Newcomb WL, et al. Abdominal wall reconstruction after temporary abdominal closure: a ten-year review. Surg Innov.

2006;13:223230.

3. Malik K, Bowers SP, Smith CD, et al. A case series of laparoscopic

components separation and rectus medialization with laparoscopic ventral

hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:607 610.

4. Milburn ML, Shah PK, Friedman EB, et al. Laparoscopically assisted components separation technique for ventral incisional hernia repair. Hernia.

2007;11:157161.

5. Rosen MJ, Jin J, McGee MF, et al. Laparoscopic component separation in the

single-stage treatment of infected abdominal wall prosthetic removal. Hernia.

2007;11:435 440.

6. Garcia GD, Freeman IH, Zagorski SM, et al. A laparoscopic approach to the

surgical management of enterocutaneous fistula in a wound healing by

secondary intention. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:554 556.

7. Kolker AR, Brown DJ, Redstone JS, et al. Multilayer reconstruction of

556 | www.annalsplasticsurgery.com

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

abdominal wall defects with acellular dermal allograft (AlloDerm) and

component separation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:36 41.

Sailes FC, Walls J, Guelig D, et al. Synthetic and biological mesh in

component separation: a 10-year single institution review. Ann Plast Surg.

2010;64:696 698.

Bluebond-Langner R, Keifa ES, Mithani S, et al. Recurrent abdominal laxity

following interpositional human acellular dermal matrix. Ann Plast Surg.

2008;60:76 80.

Poulakidas S, Kowal-Vern A. Component separation technique for abdominal

wall reconstruction in burn patients with decompressive laparotomies.

J Trauma. 2009;67:14351438.

Ekeh AP, McCarthy MC, Woods RJ, et al. Delayed closure of ventral

abdominal hernias after severe trauma. Am J Surg. 2006;191:391395.

Mackay DR, Stevenson JC. Spigelian herniation after component separation.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:155e156e.

Dragu A, Klein P, Unglaub F, et al. Tensiometry as a decision tool for

abdominal wall reconstruction with component separation. World J Surg.

2009;33:1174 1180.

Palazzo F, Ragazzi S, Ferrara D, et al. Herniated gravid uterus through an

incisional hernia treated with the component separation technique. Hernia.

2010;14:101104.

Moore M, Bax T, MacFarlane M, et al. Outcomes of the fascial component

separation technique with synthetic mesh reinforcement for repair of complex

ventral incisional hernias in the morbidly obese. Am J Surg. 2008;195:575

579.

Jin J, Rosen MJ, Blatnik J, et al. Use of acellular dermal matrix for

complicated ventral hernia repair: does technique affect outcomes? J Am Coll

Surg. 2007;205:654 660.

de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, Charbon JA, et al. Repair of giant midline

abdominal wall hernias: components separation technique versus prosthetic

repair: interim analysis of a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg.

2007;31:756 763.

Alaedeen DI, Lipman J, Medalie D, et al. The single-staged approach to the

surgical management of abdominal wall hernias in contaminated fields.

Hernia. 2007;11:41 45.

Li EN, Silverman RP, Goldberg NH. Incisional hernia repair in renal

transplantation patients. Hernia. 2005;9:231237.

Samson TD, Buchel EW, Garvey PB. Repair of infected abdominal wall

hernias in obese patients using autologous dermal grafts for reinforcement.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:523527.

Harth KC, Rosen MJ. Endoscopic versus open component separation in

complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2010;199:342346.

Butler CE, Reis SM. Mercedes panniculectomy with simultaneous component

separation ventral hernia repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:94e98e.

Bachman SL, Ramaswamy A, Ramshaw BJ. Early results of midline hernia

repair using a minimally invasive component separation technique. Am Surg.

2009;75:572577.

Rosen MJ, Williams C, Jin J, et al. Laparoscopic versus open-component

separation: a comparative analysis in a porcine model. Am J Surg. 2007;194:

385389.

Suter M, Giusti V, Heraief E, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass:

initial 2-year experience. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:603 609.

Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, de la Torree JI, Marrero I, et al. Utilization of

human cadaveric acellular dermis for abdominal hernia reconstruction. Ann

Plast Surg. 2007;58:264 267.

2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

You might also like

- Modified Rives StoppaDocument8 pagesModified Rives StoppaAndrei SinNo ratings yet

- Cam04 Peric PDFDocument4 pagesCam04 Peric PDFAlmira SrnjaNo ratings yet

- Article. Loop Ileostomy Closure After Restorative Proctocolectomy. Outcome in 1504 Patients. 2005Document8 pagesArticle. Loop Ileostomy Closure After Restorative Proctocolectomy. Outcome in 1504 Patients. 2005Trí Cương NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Anatomy. Eight Edition. Saint Louis: Mosby.: Ped PDFDocument10 pagesAnatomy. Eight Edition. Saint Louis: Mosby.: Ped PDFannisa ussalihahNo ratings yet

- Palliative Management of Malignant Rectosigmoidal Obstruction. Colostomy vs. Endoscopic Stenting. A Randomized Prospective TrialDocument4 pagesPalliative Management of Malignant Rectosigmoidal Obstruction. Colostomy vs. Endoscopic Stenting. A Randomized Prospective TrialMadokaDeigoNo ratings yet

- Ventral Hernia Repair TechniquesDocument57 pagesVentral Hernia Repair Techniquessgod34No ratings yet

- Annals of Surgical Innovation and Research: Emergency Treatment of Complicated Incisional Hernias: A Case StudyDocument5 pagesAnnals of Surgical Innovation and Research: Emergency Treatment of Complicated Incisional Hernias: A Case StudyMuhammad AbdurrohimNo ratings yet

- DTSCH Arztebl Int-115 0031Document12 pagesDTSCH Arztebl Int-115 0031Monika Diaz KristyanindaNo ratings yet

- Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Randomized Clinical Trial of Laparoendoscopic Single-SiteDocument8 pagesVersus Conventional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Randomized Clinical Trial of Laparoendoscopic Single-SitepotatoNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00464 019 06670 9Document17 pages10.1007@s00464 019 06670 9Francisco Javier MacíasNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between On Lay and in Lay Mesh in Repair of Incisional HerniaDocument15 pagesComparison Between On Lay and in Lay Mesh in Repair of Incisional HerniaAshok kumarNo ratings yet

- SMJ 60 247Document6 pagesSMJ 60 247Chee Yung NgNo ratings yet

- 3Document8 pages3polomska.kmNo ratings yet

- Infections After Laparoscopic and Open Cholecystectomy: Ceftriaxone Versus Placebo A Double Blind Randomized Clinical TrialDocument6 pagesInfections After Laparoscopic and Open Cholecystectomy: Ceftriaxone Versus Placebo A Double Blind Randomized Clinical TrialvivianmtNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDocument6 pagesLaparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDamal An NasherNo ratings yet

- Ismaeil 2018Document15 pagesIsmaeil 2018Javier ZaquinaulaNo ratings yet

- Gine 2Document9 pagesGine 2Cimpean SorinNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Document5 pagesLaparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Juan Carlos SantamariaNo ratings yet

- EzrzrzrDocument8 pagesEzrzrzrYoussef MotiaNo ratings yet

- Staples or Sutures For Chest and Leg Wounds Following Cardiovascular SurgeryDocument6 pagesStaples or Sutures For Chest and Leg Wounds Following Cardiovascular SurgeryHesty Putri HapsariNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Laparoscopic vs. Open Surgery For Rectal CancerDocument7 pagesComparison of Laparoscopic vs. Open Surgery For Rectal Cancermohammed askarNo ratings yet

- A Multicenter, Prospective Randomized Trial of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy For Infrainguinal Revascularization With A Groin IncisionDocument12 pagesA Multicenter, Prospective Randomized Trial of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy For Infrainguinal Revascularization With A Groin IncisionburhanNo ratings yet

- Mortality Secondary To Esophageal Anastomotic Leak: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesMortality Secondary To Esophageal Anastomotic Leak: Original Articlealban555No ratings yet

- Component SeparationDocument23 pagesComponent Separationismu100% (1)

- Quilting after mastectomy reduces seromaDocument5 pagesQuilting after mastectomy reduces seromabeepboop20No ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Popliteal Cyst A SystematicDocument9 pagesSurgical Treatment of Popliteal Cyst A SystematicSri KarunNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Adenocarcinoma in An Ano-Vaginal Fistula in Crohn's DiseaseDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Adenocarcinoma in An Ano-Vaginal Fistula in Crohn's DiseaseTegoeh RizkiNo ratings yet

- Full TextDocument6 pagesFull Textpqp2303No ratings yet

- Wound: Abdominal DehiscenceDocument5 pagesWound: Abdominal DehiscencesmileyginaaNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair With Tacker Only Mesh Fixation: Single Centre ExperienceDocument5 pagesLaparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair With Tacker Only Mesh Fixation: Single Centre ExperienceMudassar SattarNo ratings yet

- Hernia IngunalisDocument7 pagesHernia IngunalisAnggun PermatasariNo ratings yet

- FitulotomyDocument5 pagesFitulotomyDenis StoicaNo ratings yet

- Synthetic Versus Biological Mesh in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hérnia RepairDocument9 pagesSynthetic Versus Biological Mesh in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hérnia RepairRhuan AntonioNo ratings yet

- Posterior Urethral Valves (PUV) - Children's Hospital of PhiladelphiaDocument5 pagesPosterior Urethral Valves (PUV) - Children's Hospital of PhiladelphiaAndri Feisal NasutionNo ratings yet

- Minimizing Morbidity of Colostomy ClosureDocument6 pagesMinimizing Morbidity of Colostomy Closurealdo adityaNo ratings yet

- Methods of Colostomy Construction - No Effect On Parastomal Hernia Rate Results From Stoma-const-A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument8 pagesMethods of Colostomy Construction - No Effect On Parastomal Hernia Rate Results From Stoma-const-A Randomized Controlled TrialCharles CardosoNo ratings yet

- Is A Minor Clinical Anastomotic Leak Clinically Significant After Resection of Colorectal CancerDocument6 pagesIs A Minor Clinical Anastomotic Leak Clinically Significant After Resection of Colorectal CancerDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Total Skin-sparing Mastectomy and Immediate ReconstructionDocument8 pagesOutcomes of Total Skin-sparing Mastectomy and Immediate ReconstructionAndreea PopescuNo ratings yet

- B - Bile Duct Injuries in The Era of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomies - 2010Document16 pagesB - Bile Duct Injuries in The Era of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomies - 2010Battousaih1No ratings yet

- The SAGES Manual of Biliary SurgeryFrom EverandThe SAGES Manual of Biliary SurgeryHoracio J. AsbunNo ratings yet

- Diathermy Versus Scalpel in Transverse Abdominal Incision in Women Undergoing Repeated Cesarean Section A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesDiathermy Versus Scalpel in Transverse Abdominal Incision in Women Undergoing Repeated Cesarean Section A Randomized Controlled TrialAmlodipine BesylateNo ratings yet

- 014 - Primary-Colorectal-Cancer - 2023 - Surgical-Oncology-Clinics-of-North-AmericaDocument16 pages014 - Primary-Colorectal-Cancer - 2023 - Surgical-Oncology-Clinics-of-North-AmericaDr-Mohammad Ali-Fayiz Al TamimiNo ratings yet

- Management of Anastomotic Leaks After Esophagectomy and Gastric Pull-UpDocument9 pagesManagement of Anastomotic Leaks After Esophagectomy and Gastric Pull-UpSergio Sitta TarquiniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Windi 2Document6 pagesJurnal Windi 2Fiella Ardhilia NuchnumNo ratings yet

- Clinicopathological Staging For Colorectal CancerDocument20 pagesClinicopathological Staging For Colorectal Cancertr0xanNo ratings yet

- Perbedaan Penanganan Antara Laparoskopi Vs Open Repair Pada Perforasi GasterDocument7 pagesPerbedaan Penanganan Antara Laparoskopi Vs Open Repair Pada Perforasi GasterAfiani JannahNo ratings yet

- Colorectal TraumaDocument44 pagesColorectal TraumaicalNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0065341116000038 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0065341116000038 MainFlorin AchimNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerDocument9 pagesA Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerOtoyGethuNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerDocument9 pagesA Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerFarizka Dwinda HNo ratings yet

- s00464 013 2881 ZDocument200 pagess00464 013 2881 ZLuis Carlos Moncada TorresNo ratings yet

- Sublay Versus Underlay in Open Ventral Hernia RepairDocument7 pagesSublay Versus Underlay in Open Ventral Hernia Repairtracycui13No ratings yet

- Chevallay 2020Document17 pagesChevallay 2020Maria PalNo ratings yet

- Neutzling Et Al-2012-The Cochrane Library - Sup-1Document3 pagesNeutzling Et Al-2012-The Cochrane Library - Sup-1David Schnettler RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 2015 Laparoscopic Surgery in Abdominal Trauma A Single Center Review of A 7-Year ExperienceDocument7 pages2015 Laparoscopic Surgery in Abdominal Trauma A Single Center Review of A 7-Year ExperiencejohnnhekoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Scrotal Hitching in Reducing Scrotal Edema After Inguinoscrotal Hernia RepairDocument4 pagesEffect of Scrotal Hitching in Reducing Scrotal Edema After Inguinoscrotal Hernia RepairIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Surg Apprach EsophagectomyDocument3 pagesSurg Apprach EsophagectomyDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 AppDocument4 pagesJurnal 3 AppmaulidaangrainiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022480423002895 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0022480423002895 Mainlucabarbato23No ratings yet

- Incisional Hernia Mesh RepairDocument5 pagesIncisional Hernia Mesh Repaireka henny suryaniNo ratings yet

- Posterior CompositesDocument8 pagesPosterior CompositesnanasalemNo ratings yet

- Cavity Preparations & Tooth-Colored Restoration TechniquesDocument48 pagesCavity Preparations & Tooth-Colored Restoration TechniquesMiguel JaènNo ratings yet

- Rosen 2007Document5 pagesRosen 2007nanasalemNo ratings yet

- Objectives of The Operative DentistryDocument5 pagesObjectives of The Operative DentistrynanasalemNo ratings yet

- Define:: 1-Dental CariesDocument3 pagesDefine:: 1-Dental CariesnanasalemNo ratings yet

- 1-Define The Following:: Dental Caries Attrition Abrasion Erosion AbfractionDocument1 page1-Define The Following:: Dental Caries Attrition Abrasion Erosion AbfractionnanasalemNo ratings yet

- Rosen 2007Document5 pagesRosen 2007nanasalemNo ratings yet

- 1-Define The Following:: Dental Caries Attrition Abrasion Erosion AbfractionDocument1 page1-Define The Following:: Dental Caries Attrition Abrasion Erosion AbfractionnanasalemNo ratings yet

- AmalgmDocument91 pagesAmalgmnanasalemNo ratings yet

- Resin Composite RepairDocument12 pagesResin Composite RepairnanasalemNo ratings yet

- Complete Lower Body and Core Workout with LungesDocument3 pagesComplete Lower Body and Core Workout with LungesSerifa PasovicNo ratings yet

- RICHARD F. BAXTER-Pocket Guide To Musculoskeletal AssessmentDocument104 pagesRICHARD F. BAXTER-Pocket Guide To Musculoskeletal Assessmentmaitre1959100% (4)

- The Use of Ultrasound For Dogs and Cats in The Emergency Room AFAST TFASTDocument25 pagesThe Use of Ultrasound For Dogs and Cats in The Emergency Room AFAST TFASTdpcamposhNo ratings yet

- CTS 1 - Back PainDocument17 pagesCTS 1 - Back PainVikNo ratings yet

- Astm D4910-02Document4 pagesAstm D4910-02Saqib GhafoorNo ratings yet

- From Here To Sanguinity NumeneraDocument6 pagesFrom Here To Sanguinity NumeneraMaya KarasovaNo ratings yet

- Installing the 3-3-5 DefenseDocument216 pagesInstalling the 3-3-5 Defensejimy45100% (12)

- Transition To Anterior Approach in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Learning Curve ComplicationsDocument7 pagesTransition To Anterior Approach in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Learning Curve ComplicationsAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3: Musculoskeletal, Circulatory and Respiratory System TermsDocument6 pagesLesson 3: Musculoskeletal, Circulatory and Respiratory System TermsClaudine NaturalNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment FormDocument4 pagesRisk Assessment FormCamNo ratings yet

- Sodium Chromate Anhydrous PDFDocument6 pagesSodium Chromate Anhydrous PDFErika WidiariniNo ratings yet

- Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip ExcerptDocument22 pagesCurveball: The Year I Lost My Grip ExcerptI Read YANo ratings yet

- Vasc., 6.lymph.& 7. Inn. of The Foot 209-10Document46 pagesVasc., 6.lymph.& 7. Inn. of The Foot 209-10Ameet ThakrarNo ratings yet

- Chem M2 Laboratory Apparatus, Safety Rules & SymbolsDocument29 pagesChem M2 Laboratory Apparatus, Safety Rules & Symbolsdesidedo magpatigbasNo ratings yet

- Neurological Physiotherapy EvaluationDocument8 pagesNeurological Physiotherapy EvaluationAreeba RajaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Neuromuscular Training On Children andDocument11 pagesEffects of Neuromuscular Training On Children andJussie PereiraNo ratings yet

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)Document37 pagesCerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)Mustafa KhandgawiNo ratings yet

- Universal Classic ManualDocument32 pagesUniversal Classic Manualvitalii pinteaNo ratings yet

- BODY MECHANICS GUIDEDocument31 pagesBODY MECHANICS GUIDEAnnapurna DangetiNo ratings yet

- Treatment and Rehabilitation of Fractures (Stanley Hoppenfeld)Document1 pageTreatment and Rehabilitation of Fractures (Stanley Hoppenfeld)小蓮花No ratings yet

- CaddraGuidelines2011 ToolkitDocument48 pagesCaddraGuidelines2011 ToolkitYet Barreda BasbasNo ratings yet

- Indications and Contraindications: Massage Denotes A MoreDocument6 pagesIndications and Contraindications: Massage Denotes A MoreMiljan MadicNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Machine SafeguardingDocument68 pagesA Guide To Machine SafeguardingnaughtymalsNo ratings yet

- RICOH MPC2030 Service ManualDocument832 pagesRICOH MPC2030 Service Manualkingveli100% (4)

- A.J. Barker's Letter To Coach KillDocument9 pagesA.J. Barker's Letter To Coach KillLeslie RolanderNo ratings yet

- Corrosive Poisons IDocument28 pagesCorrosive Poisons IRoman MamunNo ratings yet

- Filing an NHRC complaint for custodial tortureDocument4 pagesFiling an NHRC complaint for custodial tortureVara Prasad NeelamsettiNo ratings yet

- OSHA 300 - Record Keeping DecisionTreeDocument1 pageOSHA 300 - Record Keeping DecisionTreeeerrddeemmNo ratings yet

- 10 Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDS)Document42 pages10 Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDS)NUR AISYAH ALYANINo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan: Caring For Patients With Head Injuries 90 MinutesDocument12 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan: Caring For Patients With Head Injuries 90 MinutesJefa Marcelo KimbonganNo ratings yet