Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Behn Meyer V Yangco

Uploaded by

evgciikOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Behn Meyer V Yangco

Uploaded by

evgciikCopyright:

Available Formats

BEHN MEYER & CO. v. TEODORO R.

YANCO

Malcolm, J.

September 18, 1918

G.R. No. 13203

Doctrine

In mercantile contracts of American origin, the letters, "F.O.B.," standing for the words "Free on Board," are

frequently used. The meaning is that the seller shall bear all expenses until the goods are delivered where

they are to be "F.O.B." According as to whether the goods are to be delivered "F.O.B." at the point of

shipment or at the point of destination determines the time when property passes.

Summary

A contract of sale was entered into by petitioner as the vendor with the defendant as the vendee. It states that

the subject matter of the sale was 80 drums of caustic soda, with 76% of Carabao brand, at the price of

$9.75 per one hundred pounds, cost, insurance, and freight included, to be shipped during March, 1916, to

be delivered to Manila and paid for on delivery of the documents. The goods were shipped from New York,

but before reaching Manila, the vessel was detained and some of the drums were confiscated so that when it

did reach its destination, Yanco refused to accept the delivery of the remaining drums and rejected

petitioners offer to wait for the rest of the shipment to arrive. Yanco then filed an action for damages, but

the petitioner argued that the former should bear the burden of the loss of merchandise because he was

already the absolute owner of the specific soda confiscated and that the place of delivery was not Manila.

However, the Court ruled, among other issues, that the word, Manila, in conjunction with the letters "c.i.f."

in the contract must mean that the contract price, covering costs, insurance, and freight, signifies that

delivery was to be made in Manila. Such a specification in a contract relative to the payment of freight

indicates the parties intention as to the place of delivery so that if the seller is to pay the freight, the

inference is strong that the duty of the seller is to have the goods transported to their ultimate destination and

that the title to the property does not pass until the goods have reached their destination. Thus, plaintiff has

not proved the performance on its part of the conditions precedent in the contract and since fulfilment of the

contract is impossible, Yanco, as the vendee, is entitled to rescind the contract of sale.

Facts

On March 7, 1916, the parties signed a memorandum or a contract of sale which provides for 80

drums of caustic soda, with 76% of Carabao brand, at the price of $9.75 per one hundred pounds,

cost, insurance, and freight included, to be shipped during March, 1916, to be delivered to Manila

and paid for on delivery of the documents. Behn, Meyer, and Co. was the vendor while Yanco was

the vendee with the selling price was P10,063.86.

Said goods were shipped onboard the steamship, Chinese Prince, from New York, but before it

reached Manila, the vessel was detained at Penang and 71 drums were confiscated. Only 9 drums

reached its destination and Yanco refused to accept it and rejected plaintiffs offer of waiting for the

remainder of the shipment until its arrival, or of accepting the substitution of seventy-one drums of

caustic soda of similar grade from plaintiff's stock.

The plaintiff then sold, for the account of the defendant, eighty drums of caustic soda from which

there was realized the sum of P6,352.89. Deducting this sum from the selling price of P10,063.86,

we have the amount claimed as damages for the alleged breach of the contract.

Ratio/Issues

(1) Whether or not Behn, Meyer, and Co. committed a breach of the contract of sale (YES)

(The Court divided the issues into three component parts.)

a) SUBJECT MATTER AND CONSIDERATION As to the offer made by the plaintiff,

the specific merchandise was never tendered, the soda it offered was not of the Carabao brand,

and that said offer was not made within the time that a March shipment, according to another

provision the contract, would normally have been available.

b) PLACE OF DELIVERY The contract provided for "c.i.f. Manila, pagadero against

delivery of documents."

Its determination always resolves itself into a question of fact. If the contract be silent

as to the person or mode by which the goods are to be sent, delivery by the vendor to a

common carrier, in the usual and ordinary course of business, transfers the property to

the vendee.

However, a specification relative to the payment of freight may be used to indicate the

parties intention as to the place of delivery so that it leads to two scenarios: If the

buyer is to pay the freight, it is reasonable to suppose that he does so because the goods

become his at the point of shipment. On the other hand, if the seller is to pay the freight,

the inference is equally so strong that the duty of the seller is to have the goods

transported to their ultimate destination and that title to property does not pass until the

goods have reached their destination.

The letters "c.i.f." found in British contracts, such as that found in the case, stand for

cost, insurance, and freight and signify that the price fixed covers not only the cost of

the goods, but the expense of freight and insurance to be paid by the seller.

(See doctrine). The terms, c.i.f. and f.o.b., merely make rules of presumption which

yield to proof of contrary intention.

Plaintiffs argue that the place of delivery was not Manila, but New York, however the

Court ruled that it would not have gone to the trouble of making fruitless attempts to

substitute goods for the merchandise named in the contract, but would have permitted

the entire loss of the shipment to fall upon the defendant if it was so.

To be noted is the fact that the bill of lading was for goods received from Neuss

Hesslein & Co. to be sent to the Bank of the Philippine Islands with a draft upon Behn,

Meyer & Co. and with instructions to deliver the same, and thus transfer the property to

Behn, Meyer & Co. when and if Behn, Meyer & Co. should pay the draft.

c) TIME OF DELIVERY - The contract provided for: "Embarque: March 1916," the

merchandise was in fact shipped from New York on the Steamship Chinese Prince on

April 12, 1916.

d) PERFORMANCE Plaintiff has not complied with his obligation under the contract and, as

contemplated by article 1451 of the Civil Code, the vendee can demand fulfillment of

the contract, and this being shown to be impossible, is relieved of his obligation. There

thus being sufficient ground for rescission, the defendant is not liable.

Held

Judgement affirmed

Prepared by: Eunice V. Guadalope [Sales | Prof. Jardeleza]

You might also like

- Netflix Streaming RightsDocument4 pagesNetflix Streaming RightsevgciikNo ratings yet

- Netflix Streaming RightsDocument4 pagesNetflix Streaming RightsevgciikNo ratings yet

- CHENG V GENATODocument2 pagesCHENG V GENATOLaurena ReblandoNo ratings yet

- 330 Ortega V Leonardo 103 Phil 870Document2 pages330 Ortega V Leonardo 103 Phil 870Taz Tanggol Tabao-Sumpingan100% (2)

- (Property) 113 - Lasam V Director of Lands DigestDocument2 pages(Property) 113 - Lasam V Director of Lands Digestchan.aNo ratings yet

- Ownership dispute over inherited landDocument4 pagesOwnership dispute over inherited landMelissa S. Chua100% (1)

- Deleste Owns Half of Disputed Land, Other Half Held in TrustDocument3 pagesDeleste Owns Half of Disputed Land, Other Half Held in TrustIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Tuason V TuasonDocument2 pagesTuason V TuasonRyan Christian100% (1)

- Pasagui V VillablancaDocument1 pagePasagui V VillablancailagankmNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Complaint EagleDocument3 pagesAffidavit Complaint EagleMelchor CasibangNo ratings yet

- Behn Meyer Vs YangcoDocument1 pageBehn Meyer Vs YangcoJanlo FevidalNo ratings yet

- Behn Meyer vs. YangcoDocument3 pagesBehn Meyer vs. YangcoJenine QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- CIF Sales DisputeDocument6 pagesCIF Sales DisputeLouise Nicole AlcobaNo ratings yet

- Behn Meyer vs. YancoDocument2 pagesBehn Meyer vs. YancoFranz MarasiganNo ratings yet

- General Foods vs. National CoconutDocument1 pageGeneral Foods vs. National CoconutJanlo FevidalNo ratings yet

- Lietz V CA DigestDocument2 pagesLietz V CA DigestMara Martinez100% (1)

- Carbonell vs. CA DigestDocument2 pagesCarbonell vs. CA DigestKing BadongNo ratings yet

- Validity of Deed of Sale Upheld Despite Bounced ChecksDocument2 pagesValidity of Deed of Sale Upheld Despite Bounced ChecksLuis MacababbadNo ratings yet

- Pacific Vegetable Oil v. Singzon: Foreign Corp Not Required License to Sue Over US ContractDocument2 pagesPacific Vegetable Oil v. Singzon: Foreign Corp Not Required License to Sue Over US Contractalwayskeepthefaith80% (1)

- Camper Realty vs. ReyesDocument2 pagesCamper Realty vs. ReyesJelyn Delos Reyes TagleNo ratings yet

- 3-8 Fabillo v. IACDocument2 pages3-8 Fabillo v. IACAnna VeluzNo ratings yet

- Florendo vs. FozDocument1 pageFlorendo vs. FozKing BadongNo ratings yet

- Bagnas v. CADocument1 pageBagnas v. CAMowanNo ratings yet

- 20 Nutrimix v. CADocument2 pages20 Nutrimix v. CARegina CoeliNo ratings yet

- Adalin v. CADocument1 pageAdalin v. CASJ Normando CatubayNo ratings yet

- Pasagui v. Villablanca SalesDocument1 pagePasagui v. Villablanca SalesJetlogzzszszsNo ratings yet

- Mindanao Acadamy V YapDocument1 pageMindanao Acadamy V Yapana ortizNo ratings yet

- (Sales) Rivera v. OngDocument2 pages(Sales) Rivera v. OngJechel TBNo ratings yet

- FERNANDO T. MATE vs. THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and INOCENCIO TANDocument2 pagesFERNANDO T. MATE vs. THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and INOCENCIO TANMartin Espinosa100% (1)

- Sta. Ana V Hernandez - G.R. No. L-16394Document2 pagesSta. Ana V Hernandez - G.R. No. L-16394Krisha Marie Tan BuelaNo ratings yet

- Villonco V BormahecoDocument3 pagesVillonco V Bormahecowesleybooks100% (2)

- Adequacy of Price in Land Sale ContractsDocument2 pagesAdequacy of Price in Land Sale ContractsAnonymous hS0s2moNo ratings yet

- Dagupan Trading Vs MacamDocument1 pageDagupan Trading Vs MacamCharlie BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Macoy v. Court of Appeals: "The Application of The Third ParagraphDocument2 pagesVda. de Macoy v. Court of Appeals: "The Application of The Third ParagraphJogie AradaNo ratings yet

- 07 Pasagui v. VillablancaDocument1 page07 Pasagui v. VillablancaAnna VeluzNo ratings yet

- Pingol V CADocument5 pagesPingol V CAFra SantosNo ratings yet

- PG 10 #17 Arches vs. de DiazDocument2 pagesPG 10 #17 Arches vs. de DiazHarry Dave Ocampo PagaoaNo ratings yet

- Imperial v. Court of Appeals 316 SCRA 393 - DigestDocument4 pagesImperial v. Court of Appeals 316 SCRA 393 - DigestErrol DobreaNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Lietz, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageRudolf Lietz, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsLeizle Funa-Fernandez100% (1)

- Dagupan Trading V Macam DigestDocument2 pagesDagupan Trading V Macam DigestRuby Reyes100% (1)

- SALES.09.Melliza Vs City of IloiloDocument2 pagesSALES.09.Melliza Vs City of IloiloPaolo Ervin PerezNo ratings yet

- Doromal Vs CA DigestDocument4 pagesDoromal Vs CA DigestblinkblitzNo ratings yet

- 75 - Misterio V Cebu State College of Science and TechnologyDocument2 pages75 - Misterio V Cebu State College of Science and TechnologyChristine Joy Angat100% (3)

- Carceller vs. Court of Appeals DIGESTDocument3 pagesCarceller vs. Court of Appeals DIGESTHortense VarelaNo ratings yet

- Land Sale Dispute Resolved (1987Document4 pagesLand Sale Dispute Resolved (1987Michael Parreño VillagraciaNo ratings yet

- 01 Del Rosario v. La BadeniaDocument2 pages01 Del Rosario v. La BadeniaBonitoNo ratings yet

- Sales Case Digest 6Document9 pagesSales Case Digest 6Alit Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Roman V GrimaltDocument2 pagesRoman V GrimaltClarence ProtacioNo ratings yet

- Felix Danguilan, Petitioner, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, Apolonia Melad, Assisted by Her Husband, JOSE TAGACAY, FactsDocument2 pagesFelix Danguilan, Petitioner, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, Apolonia Melad, Assisted by Her Husband, JOSE TAGACAY, FactsJoshua ReyesNo ratings yet

- Soler v Chesley: Liability of Seller for Late Delivery of MachineryDocument5 pagesSoler v Chesley: Liability of Seller for Late Delivery of MachineryLuis MacababbadNo ratings yet

- YU BUN GUAN v. Elvira ONG / 367 SCRA 559 (October 18, 2001) / Digest by Lara PangilinanDocument3 pagesYU BUN GUAN v. Elvira ONG / 367 SCRA 559 (October 18, 2001) / Digest by Lara PangilinanGenevieve Kristine ManalacNo ratings yet

- Bagnas V Ca DigestDocument2 pagesBagnas V Ca DigestJien Lou100% (1)

- Tagactac Vs JimenezDocument2 pagesTagactac Vs JimenezjessapuerinNo ratings yet

- Fabillo v. IacDocument1 pageFabillo v. IacMarion Nerisse KhoNo ratings yet

- Imelda Ong Quitclaim Deed UpheldDocument2 pagesImelda Ong Quitclaim Deed UpheldFrancisCarloL.FlameñoNo ratings yet

- Roberts v. PapioDocument2 pagesRoberts v. PapioJazz Tracey100% (1)

- Onerous Donations RequirementDocument2 pagesOnerous Donations RequirementPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Rural Bank V CA Digest - Law On SalesDocument3 pagesConsolidated Rural Bank V CA Digest - Law On SalesBea Czarina NavarroNo ratings yet

- Sales - Jose Sta. Ana Vs Rosa HernandezDocument1 pageSales - Jose Sta. Ana Vs Rosa HernandezPatricia Blanca Ramos100% (1)

- 06 Hernaez V HernaezDocument1 page06 Hernaez V HernaezMark Anthony Javellana SicadNo ratings yet

- Mercado V EspinosillasDocument2 pagesMercado V EspinosillasLeiaVeracruzNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Behn Meyer Vs YangcoDocument3 pagesCase Digests Behn Meyer Vs YangcoLouise Nicole AlcobaNo ratings yet

- Behn Meyer V Teodoro YancoDocument1 pageBehn Meyer V Teodoro YancoEmi SicatNo ratings yet

- COVID-Proofing Your Business and Workplace NotesDocument5 pagesCOVID-Proofing Your Business and Workplace NotesevgciikNo ratings yet

- Ang NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestDocument2 pagesAng NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestevgciikNo ratings yet

- Migedc ForumDocument1 pageMigedc ForumevgciikNo ratings yet

- Iloilo - First City in Asia Where 3 Properties Were Sold For Cryptocurrencies - The Economic TimesDocument10 pagesIloilo - First City in Asia Where 3 Properties Were Sold For Cryptocurrencies - The Economic TimesevgciikNo ratings yet

- Ang NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestDocument2 pagesAng NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestevgciikNo ratings yet

- Senators Question Reduced Budget For Housing Dep't - BusinessWorldDocument4 pagesSenators Question Reduced Budget For Housing Dep't - BusinessWorldevgciikNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Commission Implementation of Prior Year's (2017) RecommendationsDocument4 pagesClimate Change Commission Implementation of Prior Year's (2017) RecommendationsevgciikNo ratings yet

- Calendar of EventsDocument2 pagesCalendar of EventsevgciikNo ratings yet

- Notes For Sustainable HousingDocument5 pagesNotes For Sustainable HousingevgciikNo ratings yet

- SB No. 1934 seeks to prohibit SOGIESC discriminationDocument5 pagesSB No. 1934 seeks to prohibit SOGIESC discriminationevgciikNo ratings yet

- Silas V.Guadalope: Professional SummaryDocument1 pageSilas V.Guadalope: Professional SummaryevgciikNo ratings yet

- Ang NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestDocument2 pagesAng NARS vs. Executive Secretary DigestevgciikNo ratings yet

- Name Location Time Services Offered and PriceDocument3 pagesName Location Time Services Offered and PriceevgciikNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss: ST NDDocument1 pageAffidavit of Loss: ST NDevgciikNo ratings yet

- Kadamay PhillippinesDocument5 pagesKadamay PhillippinesevgciikNo ratings yet

- Notice To Fill-Up The Vacant Position in Central OfficeDocument1 pageNotice To Fill-Up The Vacant Position in Central OfficeevgciikNo ratings yet

- NEDA ThresholdDocument1 pageNEDA ThresholdevgciikNo ratings yet

- Panlungsod Shall Provide OtherwiseDocument1 pagePanlungsod Shall Provide OtherwiseevgciikNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Japan and PH Law in Terms of Evacuation and Volcanic EruptionDocument4 pagesDifference Between Japan and PH Law in Terms of Evacuation and Volcanic EruptionevgciikNo ratings yet

- NEDA ThresholdDocument1 pageNEDA ThresholdevgciikNo ratings yet

- The Proposed Moratorium Under This Bill Is DifferentDocument1 pageThe Proposed Moratorium Under This Bill Is DifferentevgciikNo ratings yet

- DA Budget Hearing Report 9 OctoberDocument3 pagesDA Budget Hearing Report 9 OctoberevgciikNo ratings yet

- Legal Asst Fund PDFDocument3 pagesLegal Asst Fund PDFevgciikNo ratings yet

- Legal Asst Fund PDFDocument3 pagesLegal Asst Fund PDFevgciikNo ratings yet

- Marshal ServiceDocument4 pagesMarshal ServiceevgciikNo ratings yet

- Arnel Sanchez Paper PDFDocument98 pagesArnel Sanchez Paper PDFevgciikNo ratings yet

- Arnel Sanchez Paper PDFDocument98 pagesArnel Sanchez Paper PDFevgciikNo ratings yet

- LAW 129-B Module 1 (Estate Tax) AY 2017Document2 pagesLAW 129-B Module 1 (Estate Tax) AY 2017evgciikNo ratings yet

- Petition For Issuance of 2nd OwnersDocument4 pagesPetition For Issuance of 2nd OwnersArnold Onia100% (1)

- Mike Milanovich and Virginia Milanovich v. United States, 275 F.2d 716, 4th Cir. (1960)Document11 pagesMike Milanovich and Virginia Milanovich v. United States, 275 F.2d 716, 4th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Secured Financing MollDocument142 pagesSecured Financing MollJmjurenNo ratings yet

- Central Bank V CA ObliCon Case DIGESTDocument1 pageCentral Bank V CA ObliCon Case DIGESTCharlyn ReyesNo ratings yet

- TAMIL NADU PRISON MANUAL - Updated PDFDocument452 pagesTAMIL NADU PRISON MANUAL - Updated PDFmaharajanpal73% (11)

- PNB vs Davao Sunrise dispute over interest rates in loan agreementsDocument51 pagesPNB vs Davao Sunrise dispute over interest rates in loan agreementsJaysonNo ratings yet

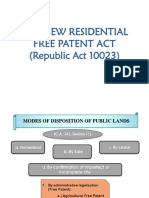

- The New Residential Free Patent Act (Republic Act 10023)Document17 pagesThe New Residential Free Patent Act (Republic Act 10023)Memphis RainsNo ratings yet

- Cebu Winland v. OngDocument4 pagesCebu Winland v. OngNerry Neil TeologoNo ratings yet

- Present: Smti. Minakshi Rongpi Additional Sessions JudgeDocument17 pagesPresent: Smti. Minakshi Rongpi Additional Sessions JudgeA Common Man MahiNo ratings yet

- Jairajsinh Temubha JadejaDocument10 pagesJairajsinh Temubha JadejaSankul KabraNo ratings yet

- REMEDIAL LAW BAR EXAMINATION QUESTIONSDocument11 pagesREMEDIAL LAW BAR EXAMINATION QUESTIONSAubrey Caballero100% (1)

- CIR v. CA: Non-retroactive application of BIR rulings absent bad faithDocument2 pagesCIR v. CA: Non-retroactive application of BIR rulings absent bad faithJames Ryan AlbaNo ratings yet

- Business & Trade Law Tutorials: Legal Framework, Contract FormationDocument12 pagesBusiness & Trade Law Tutorials: Legal Framework, Contract FormationCassandra LimNo ratings yet

- Lopez vs. OmbudsmanDocument1 pageLopez vs. OmbudsmanMichael Rentoza100% (1)

- Miscellaneous Sales PatentDocument3 pagesMiscellaneous Sales PatentAllan ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Art 22 Law 201Document24 pagesArt 22 Law 201Anjali MakkarNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Penal CodeDocument2 pagesPakistan Penal CodeSalman Ali MastNo ratings yet

- Tallado v. COMELECDocument2 pagesTallado v. COMELECEva Trinidad100% (3)

- Manila Race Horse v. Dela FuenteDocument4 pagesManila Race Horse v. Dela FuenteMadelle Pineda100% (1)

- Vivencio Dalit V.S. Spouses BalagtasDocument3 pagesVivencio Dalit V.S. Spouses BalagtasSORITA LAWNo ratings yet

- RUSTICO ABAY, JR. and REYNALDO DARILAG vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, (G.R. No. 165896, September 19, 2008.)Document2 pagesRUSTICO ABAY, JR. and REYNALDO DARILAG vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, (G.R. No. 165896, September 19, 2008.)Eileithyia Selene SidorovNo ratings yet

- 01 Gercio Vs Sunlife AssuranceDocument2 pages01 Gercio Vs Sunlife AssurancePiaNo ratings yet

- Leung vs. O'Brien, 28 Phil. 182 G.R. No. L-13602 April 6, 1918Document2 pagesLeung vs. O'Brien, 28 Phil. 182 G.R. No. L-13602 April 6, 1918Lu CasNo ratings yet

- DENR Report on Land ApplicationDocument2 pagesDENR Report on Land ApplicationJomar FrogosoNo ratings yet

- Latin Legal TermsDocument37 pagesLatin Legal TermsEngelov AngtonivichNo ratings yet

- United States v. Claude Verbal, II, 4th Cir. (2015)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Claude Verbal, II, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Approaches To Evidence ActDocument6 pagesWeek 1: Approaches To Evidence ActLee .CJNo ratings yet

- NGA Vs MagcamitDocument4 pagesNGA Vs Magcamitapple_doctoleroNo ratings yet

- Mercantile Law: Topics PagesDocument7 pagesMercantile Law: Topics PagesAngel Eilise0% (1)