Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial Infarction

Uploaded by

kakarafnieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial Infarction

Uploaded by

kakarafnieCopyright:

Available Formats

Cardiology Journal

2010, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 319324

Copyright 2010 Via Medica

ISSN 18975593

HOW TO DO

Psychological support for patients

following myocardial infarction

Anna Mierzyska, Monika Kowalska, Monika Stepnowska, Ryszard Piotrowicz

Department of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Non-Invasive Electrocardiology,

Institute of Cardiology, Warsaw, Poland

Abstract

The paper presents the principal psychological problems in patients following myocardial

infarction. Particular emphasis has been placed on anxiety and depression following myocardial infarction and behavioural patterns adversely affecting health. A proposal of actions

during cardiac rehabilitation has been presented in accordance with the severity of psychological problems encountered in the patients. (Cardiol J 2010; 17, 3: 319324)

Key words: myocardial infarction, psychological

Introduction

Abnormalities of cardiovascular function (coronary

artery disease caused by atherosclerosis) are referred

to as diseases of major public health importance and

their development and course are strongly related to

the patients psychosocial functioning, lifestyle and

behavioral patterns. The high mortality rate, serious

health consequences and the necessity to introduce

numerous changes in everyday functioning after the

diagnosis and hospitalization are the reasons why cardiovascular disease is perceived by patients as one of

the most serious and threatening life experiences.

For these reasons the psychological care of cardiac patients is a very important element of treatment and should include a wide scope of functions

performed by the patient, mainly understood as supporting the adjustment to the new conditions of life

associated with the consequences of becoming ill.

We address the issues related to myocardial

infarction and its consequences for the psychological functioning of the patient.

Psychological responses of patients

following myocardial infarction

The risk factors of myocardial infarction are

divided into several categories with an important

role being played by psychosocial factors, such as

chronic stress, fast-paced life, type A behavioral

pattern (TABP), having too many responsibilities,

inability to cope, a considerable accumulation of important life events, depression, anxiety and social

isolation.

The warning signs are often ignored or misinterpreted by the patients, which makes the onset of myocardial infarction a big surprise for

them. Myocardial infarction is associated with

a high level of anxiety, the fear of impending death

and deep frustration resulting from the sudden

and serious changes in functioning. The feeling of

danger additionally exacerbates the need for

hospitalization and its consequences reach deep

into the future and significantly affect the patients

quality of life (Table 1).

Address for correspondence: Anna Mierzyska, MA, Department of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Non-Invasive Electrocardiology,

Institute of Cardiology, ul. Alpejska 42, 04628 Warszawa, Poland, e-mail: anna.mierzynska@ikard.pl

Received: 19.03.2010

Accepted: 8.04.2010

www.cardiologyjournal.org

319

Cardiology Journal 2010, Vol. 17, No. 3

Table 1. Psychological responses to experiencing myocardial infarction.

Anxiety

Sadness

Depressed mood

Anger

Depression

Surprise

Agoraphobia

Disgust

Exhaustion

Social withdrawal

Hostility

Other psychological responses

following myocardial infarction

Anxiety reactions

Intense anxiety is often listed as the major psychological response to myocardial infarction and is

one of the symptoms associated with this condition.

Anxiety is described as an unpleasant emotional

state coincident with the fear of danger and a number of cognitive changes (e.g. impaired concentration, impaired memory, impaired ability of logical

thinking) and somatic changes (e.g. rapid heart rate,

dry mouth, agitation). Soon after the cardiovascular event the level of anxiety is elevated in about

two thirds of the patients and reaches clinical levels in 2030%.

The high level of anxiety observed following

myocardial infarction should be considered from two

perspectives. On the one hand, it is a response to

a condition which reduces the quality of life, while on

the other hand, it coexists with a number of factors

increasing the risk of reinfarction in the future, as

anxiety disorders have been proved to coexist with

hypertension, high cholesterol levels, smoking (including nicotine dependence), alcohol and drug

abuse and with obesity [13].

Some patients cope with anxiety by denying the

presence of the disease and ignoring endangering

signals. In the first stage following myocardial infarction this mechanism reduces the level of negative emotions and may positively affect the patients

functioning. In the long run, however, it impedes

the patients confrontation with the consequences

of the disease. Such patients are less motivated to

undergo treatment and rehabilitation and to comply with the doctors directions [4]. The likelihood

of medical complications in the future is therefore

increased.

Depressed mood and depression

Depressed mood is a common response to

myocardial infarction. Between 20% and 30% of the

patients hospitalized for myocardial infarction manifest mild to severe depressive symptoms. As many

as 60% of patients referred for coronary angiogra-

320

phy show symptoms of depression, which, coupled

with ischemic heart disease, considerably impairs

their functioning, the chances of recovering and the

prognosis [5]. Coexistence of depression and

a somatic disorder affect the patients health to

a much greater degree than coexistence of two somatic disorders [6]. In addition a considerable percentage of patients following acute myocardial infarction (3848%) report a depressive episode shortly before the infarction [7].

In addition to anxiety and depression the psychological responses following myocardial infarction

may include agoraphobia (triggered by catastrophic thinking), exhaustion, hostility and health-related sadness, anger, the feeling of surprise and disgust [8].

Post-myocardial infarction patients may also

show a tendency to social withdrawal. Studies indicate that one third (3135%) of patients following

myocardial infarction show limited participation in

social activities during the first year after infarction.

A similar percentage of patients (2733% of women and 2228% of men) show a low level of social

anchoring [9] described as participation in formal

and informal social groups [10].

Psychological functioning

following myocardial infarction

The physical and psychological consequences

of ischemic heart disease contribute to a considerable impairment of the quality of life in all dimensions, both physical and mental ones [5, 9]. The

experience of myocardial infarction also affects the

ability to achieve life goals. The obstacles interfering with the attainment of these life goals are associated with a higher level of stress and a lower

health-related quality of life after hospitalization [11].

Gender-related differences are essential to

coping with the consequences of myocardial infarction. Men manifest a higher level of anxiety about

their health, while women show a more pronounced

tendency to manifest avoidance behaviors [8].

The time factor is extremely important in coping with the consequences of ischemic heart disease. Within the first year following myocardial infarction patients show an increasing effectiveness

of coping with the physical consequences [9]. Also,

with time, the health-related quality of life increases. However, about 20% of the patients show signs

of reduced quality of life related to emotional func-

www.cardiologyjournal.org

Anna Mierzyska et al., Psychological support for patients following MI

Figure 1. A hierarchy of psychological influences on patients following myocardial infarction according to the

severity of psychological problems related to the somatic status and treatment stage.

tioning even 35 years after their infarction. The

high level of anxiety and stress following myocardial infarction coexists with the difficulties to make

the necessary life changes.

It is estimated that the highest quality of life

in the first year following myocardial infarction is

reported by patients who had the ability to take

advantage of various forms of social support: children, partners, friends, grandchildren. Patients who

received support from their closest ones at the time

of the illness and strengthened their family relations, reported a better functioning and health-related quality of life during the first year following

myocardial infarction. In addition, a significant improvement in the quality of life was also noticed by

patient who completed a full cardiac rehabilitation

programme and returned to work or other forms of

activity carried out before the infarction [9]. For this

reason it is very important to strengthen the feeling of control over ones own health, believing in

oneself and see the benefits of rehabilitation.

Goals of psychological support

following myocardial infarction

Psychological support for patients following

myocardial infarction is focused on several areas:

secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease,

support in the adjustment to the disease, to its consequences and to its treatment, modification of behavioral patterns that are harmful for health and

reduction of the level of anxiety and stress caused

by this experience (Fig. 1).

Secondary prevention

of ischemic heart disease

Secondary prevention aims to change the patients lifestyle and health habits with the view to

minimizing the risk of health deterioration. It involves a number of areas of patient activity. Collaboration of the patient with the psychologist concentrates on forming a favorable attitude towards

the disease or forming an adequate image of the

www.cardiologyjournal.org

321

Cardiology Journal 2010, Vol. 17, No. 3

disease and of its treatment. The amount of knowledge about the disease, its causes, its consequences and expectations regarding treatment outcomes

is the cognitive representation of the disease. The

cognitive representation refers to giving the meaning to the symptoms of the disease, predicting its

course, duration and consequences and predicting

the ways in which it can be controlled and treated

[12]. Having an adequate knowledge about the disease is essential for behaviors related to treatment

and experience of the cardiac episode. These behaviours include, among other things, the promptness of decision to call for an ambulance, the propensity to make changes in ones lifestyle (diet and

physical activity) and the readiness to return to

work. An adequate perception of the consequences of the disease and the control over the recovery

process contributes to the motivation to comply

with the doctors directions and completion of a full

cardiac rehabilitation program [13].

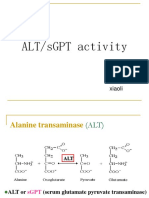

Figure 2. Type A behavioral pattern (TABP).

Reducing the level of anxiety

In the process of providing psychological support to patients following myocardial infarction

a particular emphasis is placed on interventions reducing the severity of anxiety symptoms. Patients

with severe symptoms of anxiety and depression

are more prone to look for the causes of their disease in the sphere of mental functioning. This affects the possibilities of coping with the consequences of myocardial infarction [14]. Studies show

that the severity of anxiety may be the reason why

patients give up participation in prevention and rehabilitation programs [13]. On the other hand, taking advantage of psychological support (for instance,

in the form of psychoeducation and psychological

counseling for the patient and his or her family)

considerably reduces the severity of anxiety and

depressive symptoms [15], contributes to increased

motivation to undergo rehabilitation and increases

the level of physical activity.

Modification of behavioral patterns

Modifying behavioral patterns is a very important aspect of work with cardiac patients. Some of

the important risk factors for ischemic heart disease

include type A behavioral pattern and type D personality.

Type A behavioral pattern is characterized

by a readiness to extreme competitiveness in the

fight for achievements, the feeling of excessive responsibility, aggressiveness and hostility (usually

hidden hostility), impatience, excessive excitability

and constant rush in speaking and behaving (Fig. 2).

322

Figure 3. Characteristics of type D personality.

The mechanisms linking TABP and ischemic heart disease are of behavioral and pathophysiological nature [16]. The behavioral mechanisms include behaviors harmful for health, such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and inappropriate diet. The direct

pathophysiological mechanisms include increased

heart rate, significantly increased blood pressure in

response to stimuli, elevated cortisol levels and

elevated catecholamine levels.

Type D personality is characterized by a tendency to experience negative emotions in different

types of situation along with a propensity to suppress the expression of emotions and behaviors in

social contacts (Fig. 3). Patients with this type of

personality often feel unhappy, tend to worry, are

easy to irritate, have low self-esteem, create distance in social relations and are introvert. Numer-

www.cardiologyjournal.org

Anna Mierzyska et al., Psychological support for patients following MI

ous studies suggest a significant effect of type D

personality on mortality related to ischemic heart

disease and on the severity of cardiovascular symptoms [17]. Working with automatic negative

thoughts and behavioral patterns leading to the suppression of the expression of emotions and needs

may positively affect psychosocial functioning and

prognosis in patients with ischemic heart disease.

lect the most effective form of psychological intervention. Patients following myocardial infarction

who are provided with psychological support during and after hospitalization have a higher quality

of life and significantly lower risk of reinfarction in

the future.

Other goals of psychological support

The author appreciate help of Pawe Baka with

preparation of the authorized English version of the

manuscript.

The authors do not report any conflict of interest regarding this work.

Psychological interventions are also aimed to

increase the possibility of recognizing ones own

difficulties and coping strategies and to increase the

awareness of signals sent by the body, which may

help the patient to more rapidly respond to potential health-threatening situations. At the same time

the patient undergoes training of abilities to cope

with the physiological symptoms of stress, express

emotions and needs in interpersonal relations, reduce the level of hostility, the feeling of identity in

the illness (self-picture of a patient). In situations

where the patient finds it difficult to cease smoking, collaboration with the psychologist involves

fighting the tobacco dependence.

In order to increase the quality of life at the

time of illness and to achieve positive effects of

coping with the consequences of myocardial infarction it is important to create or enhance coping

based on confronting ones current health situation,

optimism and belief in oneself and ones possibilities [9]. It is important that the patient learns to

reduce the stress by controlling its physiological

aspects. Studies show that relaxation exercises

(progressive relaxation or qigong) improve mental

functioning (reduces the level of anxiety and improves the self-perceived quality of life) and somatic

functioning (by reducing blood pressure and heart

rate, for instance) [18].

Acknowledgements

References

1. Barger SD, Sydeman SJ. Does generalized anxiety disorder predict coronary heart disease risk factors independently of major

depressive disorder. J Affect Disord, 2005; 88: 8791.

2. Gomez-Caminero A, Blumentals WA, Russo LJ, Brown RR,

Castilla-Puentes R. Does panic disorder increase the risk of coronary heart disease? A cohort study of a national managed care

database. Psychosom Med, 2005; 67: 688691.

3. Patten SB, Liu MF. Anxiety disorders and cardiovascular disease determinants in a population sample. Int J Ment Health,

(serial online), 2007; 4: 2 (Available from: Academic Search

Complete, Ipswich, MA).

4. Levine J, Warrenburg S, Kerns R et al. The role of denial in

recovery from coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med, 1987;

49: 109117.

5. Sawicka J, Jurkowska G, Bachrzewska-Gajewska H, Dobrzycki S.

Evaluation of the quality of life and frequency of depressive

symptoms In patients with coronary hart disease before planned

coronarography. Przegl Kardiodiabet, 2008; 3: 2327.

6. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E et al. Depression chronic

diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World

Health Surveys. Lancet, 2007; 370: 851858.

7. Fiedling R. Cognition, control, and mood during recovery from

AMI. Abstr Int Conf Health Psychol B. P. S. UK 1998.

8. Bowman G, Watson R, Trotman-Beasty A. Primary emotions in

patients after myocardial infarction. J Adv Nurs, 2006; 53: 636645.

9. Kristofferzon M-L, Lfmark R, Carlsson M. Coping, social sup-

Conclusions

port and quality of life over time after myocardial infarction.

Patients following myocardial infarction may

find it difficult to adjust to their new health situation. These difficulties may take the form of depressive or anxiety reactions and impaired social functioning. The psychological problems encountered

during cardiac rehabilitation may considerably interfere with recovery and reduce the motivation to

undergo treatment and comply with the doctors

directions. For this reason it is important that the

patients are provided with psychological support.

Getting to know the patients individual traits (e.g.

personality type, level of anxiety) and his or her life

situation (e.g. level of social support) helps to se-

J Adv Nurs, 2005; 52: 113124.

10. Hanson BS, stergren P-O, Elmsthl S, Isacsson S-O, Ranstam J.

Reliability and validity assessments of measures of social networks, social support and control results from the Malm

Shoulder and Neck Study. Scand J Soc Med, 1997; 25: 249257.

11. Boersma SN, Maes S, Joekes K. Goal disturbance in relation to

anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res, 2005; 14: 22652275.

12. Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, Diefenbach M,

Leventhal E, Patric-Miller L. Illness representation: Theoretical foundations. In: Wienman PKJ ed. Perceptions of health and

illness. Harwood Academic Publishers, Singapore 1946.

13. Yohannes AM, Yalfani A, Doherty P, Bundy C. Predictors of

drop-out from an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programme.

Clin Rehabil, 2007; 21: 222229.

www.cardiologyjournal.org

323

Cardiology Journal 2010, Vol. 17, No. 3

14. Day RC, Freedland KE, Carney RM. Effects of anxiety and depres-

17. Pedersen SS, Denollet J. Is type D personality here to stay?

sion on heart disease attributions. Int J Behav Med, 2005; 12: 2429.

Emerging evidence across cardiovascular disease patient groups.

15. Yoshida T, Kohzuki M, Yoshida K et al. Physical and psychological

improvements after phase II cardiac rehabilitation in patients

with myocardial infarction. Nurs Health Sci, 1999; 1: 163170.

Curr Cardiol Rev, 2006; 2, 205213.

18. Ngor Hui P, Wan M, Kwong Chan W, Man Bun Yung P. An

evaluation of two behavioral rehabilitation programs, qigong

16. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychologi-

versus progressive relaxation, in improving the quality of

cal factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and

life in cardiac patients. J Altern Complement Med, 2006; 12:

implications for therapy. Circulation, 1999; 99: 21922217.

373378.

324

www.cardiologyjournal.org

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakakakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Association Between Obesity and The Trends Of.22Document7 pagesAssociation Between Obesity and The Trends Of.22kakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Journal Frekuensi Migren Pada RADocument4 pagesJournal Frekuensi Migren Pada RAanggiNo ratings yet

- JCN 11 E34Document8 pagesJCN 11 E34kakarafnieNo ratings yet

- JCN 11 E34Document8 pagesJCN 11 E34kakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3Document8 pagesJurnal 3kakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka SarafDocument3 pagesDaftar Pustaka SarafkakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka SarafDocument3 pagesDaftar Pustaka SarafkakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Psychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial InfarctionDocument6 pagesPsychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial InfarctionkakarafnieNo ratings yet

- AffDocument5 pagesAffAnonymous I1wERnYPNo ratings yet

- JCN 11 E34Document8 pagesJCN 11 E34kakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Before and After State-Wide Smoking BansDocument5 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Before and After State-Wide Smoking BanskakarafnieNo ratings yet

- Psychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial InfarctionDocument6 pagesPsychological Support For Patients Following Myocardial InfarctionkakarafnieNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Automated DatabasesDocument14 pagesAutomated DatabasesAnilkumar Sagi100% (4)

- Psychiatric TriageDocument30 pagesPsychiatric TriageastroirmaNo ratings yet

- Experimental Design in Clinical TrialsDocument18 pagesExperimental Design in Clinical Trialsarun_azamNo ratings yet

- Deep Breathing and Coughing Exercises - Teaching PlanDocument3 pagesDeep Breathing and Coughing Exercises - Teaching Planアンナドミニク80% (5)

- Suture Size: SmallestDocument2 pagesSuture Size: SmallestGeraldine BirowaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Handbook On Adult Immunization 2012 PDFDocument140 pagesPhilippine Handbook On Adult Immunization 2012 PDFLinius CruzNo ratings yet

- Actividad y Traducciones de Terminos Medicos + AdjetivosDocument2 pagesActividad y Traducciones de Terminos Medicos + AdjetivosJosue CastilloNo ratings yet

- SgotsgptDocument23 pagesSgotsgptUmi MazidahNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument2 pagesDrug StudyRuby SantillanNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection AmongDocument77 pagesPrevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection AmongAbigailNo ratings yet

- Intranatal Assessment FormatDocument10 pagesIntranatal Assessment FormatAnnapurna Dangeti100% (1)

- Achya - 3Document11 pagesAchya - 3Jannah Miftahul JannahNo ratings yet

- Potassium Chloride GuidelinesDocument25 pagesPotassium Chloride GuidelinesYasser Gebril86% (7)

- 3214Document8 pages3214hshobeyriNo ratings yet

- 2004 Yucha-Gilbert Evidence Based Practice BFDocument58 pages2004 Yucha-Gilbert Evidence Based Practice BFdiego_vega_00No ratings yet

- Nursing Care For HipopituitarismeDocument10 pagesNursing Care For Hipopituitarismevita marta100% (1)

- Comparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyDocument9 pagesComparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Remifentanyl For Pain LaborDocument11 pagesJurnal Remifentanyl For Pain LaborAshadi CahyadiNo ratings yet

- 1238-Article Text-5203-1-10-20220916Document3 pages1238-Article Text-5203-1-10-20220916srirampharmNo ratings yet

- 108 New Charm, CharmaidDocument3 pages108 New Charm, CharmaidAmit Kumar PandeyNo ratings yet

- Physical FormDocument4 pagesPhysical Formapi-352931934No ratings yet

- Advanced EndodonticsDocument375 pagesAdvanced EndodonticsSaleh Alsadi100% (1)

- Bliss Makanza - Caregiver PDFDocument2 pagesBliss Makanza - Caregiver PDFBuhle M.No ratings yet

- Acupressure Points For Knee PainDocument7 pagesAcupressure Points For Knee Painلوليتا وردةNo ratings yet

- 3A - Hospital PharmacyDocument13 pages3A - Hospital PharmacyekramNo ratings yet

- Koch PostulatesDocument1 pageKoch PostulatescdumenyoNo ratings yet

- Providing First Aid and Emergency ResponseDocument161 pagesProviding First Aid and Emergency ResponseTHE TITANNo ratings yet

- CPG Pediatric Eye and Vision ExaminationDocument67 pagesCPG Pediatric Eye and Vision ExaminationsrngmNo ratings yet

- 01f2 - ICD vs. DSM - APA PDFDocument1 page01f2 - ICD vs. DSM - APA PDFfuturistzgNo ratings yet