Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perspective: New England Journal Medicine

Uploaded by

pututOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perspective: New England Journal Medicine

Uploaded by

pututCopyright:

Available Formats

The

NEW ENGLA ND JOURNAL

of

MEDICINE

Perspective

april 12, 2012

Warning: Contraceptive Drugs May Cause Political Headaches

R. Alta Charo, J.D.

oster Friess, a conservative political donor, recently discounted the importance of insurance

coverage for contraceptives, saying, Back in my

days, they used Bayer Aspirin for contraception.

The gals put it between their

knees, and it wasnt that costly.

Though his comment stunned

interviewer Andrea Mitchell, it at

least focused on the issue of contraceptives. Most critics of the

federal effort to ensure access to

contraceptives have reframed the

issue as a war on religion. And

as Georgetown University theologian Tom Reese told National

Public Radio in early February,

If the argument is over religious

liberty, the bishops win. If the

argument is over contraceptives,

the administration wins. Indeed, a 501(c)(4) advocacy group,

Conscience Cause, has already

been formed to leverage media to

spur legislative action and promote the view that this debate is

not about contraception, but rather about freedom and the protection of our religious values.

Since the average American

woman spends 5 years pregnant

(or trying to be) and 30 years trying not to get pregnant, nearly

99% of sexually active women

have used birth control. And the

most effective contraceptives

such as the birth-control pill and

intrauterine devices (IUDs) are

unavailable except by prescription,

which makes them part of the

health care system rather than

merely a lifestyle choice akin to

eschewing cosmetics. That such

contraceptives constitute health

care is even clearer when one considers the reduction of maternal

and neonatal morbidity and mortality from the spacing out of

births or the use of oral contraceptives for conditions ranging from

acne to uterine fibroid tumors.

But contraceptives can be

pricey. Birth-control pills can run

$600 per year, and an IUD may

cost $1,000, so many women favor

less expensive, albeit less reliable,

options such as condoms and

even withdrawal. Insurance coverage allows women to have a genuine choice. As the Institute of

Medicine recommended, under the

Affordable Care Act, insured

women will qualify for contraceptives without copayments, as part

of a range of preventive services.

n engl j med 366;15 nejm.org april 12, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 19, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1361

PERSPE C T I V E

Contraceptive Drugs may cause political headaches

State Policies on Contraceptive Coverage*

28 states require insurers that cover prescription drugs to provide coverage of the

full range of contraceptive drugs and devices approved by the Food and

Drug Administration; 17 of these states also require coverage of related

outpatient services.

2 states exclude emergency contraception from the required coverage.

1 state excludes minor dependents from coverage.

20 states allow certain employers and insurers to refuse to comply with the mandate;

8 states have no such provision that permits refusal by some employers or

insurers.

4 states include a limited refusal clause that allows only churches and church

associations to refuse to provide coverage and does not permit hospitals

or other entities to do so.

7 states include a broader refusal clause that allows churches, associations of

churches, religiously affiliated elementary and secondary schools, and potentially some religious charities and universities to refuse, but not hospitals.

8 states include an expansive refusal clause that allows religious organizations,

including at least some hospitals, to refuse to provide coverage; 2 of these

states also exempt secular organizations with moral or religious objections.

(An additional state, Nevada, does not exempt any employers but allows

religious insurers to refuse to provide coverage; 2 other states exempt insurers in addition to employers.)

14 of the 20 states with exemptions require employees to be notified when

their health plan does not cover contraceptives.

4 states attempt to provide access for employees when their employer refuses

to offer contraceptive coverage, generally by allowing employees to purchase the coverage on their own but at the group rate.

* Information is from the Guttmacher Institute, Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives

(www.guttmacher.org/sections/contraception.php).

The Obama administration exempted houses of worship from

the requirement of offering employees health insurance covering

contraception a more generous

policy than those of many of the

28 states already requiring insurers to cover contraceptives (see

box). But the exemption initially

didnt apply to institutions such as

hospitals and universities whose

fundamental purpose was nonreligious, even if the institution

was affiliated with a religious sect.

Such institutions are typically subject to generally applicable laws

for their nonreligious functions,

such as civil rights laws prohibiting employment discrimination

outside the context of ministerial

1362

functions. And the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

had already determined that singling out contraception from prescription-drug and preventive-care

coverage is a form of sex discrimination forbidden by Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act, with no exemption for religious employers.1

Nonetheless, amid growing conflict, the administration expanded its exemptions to include religiously affiliated hospitals and

universities, deciding instead that

their contracted insurance companies would be required to cover

contraceptives without any financial support from the institutions.

The goal was to ensure that

women have all the recommended

preventive-care coverage while

eliminating even tenuous financial

connections between religious employers and contraception benefits.

Yet at least seven states Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Oklahoma,

Nebraska, South Carolina, and

Texas are joining lawsuits to

overturn the requirement. And

some states are considering bills

that would allow insurance companies to ignore the federal rules.

Measures in Idaho, Missouri, and

Arizona would extend the exemptions to secular insurers or businesses, and the Senate defeated

a similar measure by a narrow

margin.

Despite the administrations

accommodations, the policys opponents have reframed it as discrimination against religious organizations even against

religion itself. It has thus become

yet another simmering health

care controversy like the debate

over religiously based refusals to

prescribe or dispense contraceptives a debate that remains

unsettled, as witnessed by the

yo-yo pattern of decisions in the

challenge to Washington States

requirement that pharmacies dispense contraceptives. (The latest

decision favored the pharmacists

who did not want to dispense

contraceptives on grounds of personal conscience or religion; the

case is again heading for appeal.)

But the current controversy is not

about a personal reluctance to directly facilitate another persons

action that one believes is immoral, even if the actor does not. Instead, it relates to passive forms

of alleged complicity that are far

more tenuous, and it touches on

the ways in which a multicultural

society cross-subsidizes the choices of its varied citizens. In other

n engl j med 366;15 nejm.org april 12, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 19, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERSPECTIVE

words, employee benefits are now

embroiled in the struggle for the

public square.

There are at least two competing views about how to organize

our public institutions, public

places, and public duties. In one

vision, individuals may exercise

their freedom to act on their religious dictates even if their acts

limit access to public goods by

people who follow a different

creed. A police officer, for example, argued in federal court that

he ought not to be required to

provide protection to a casino because he believed gambling was

sinful.2 The competing view is

that people performing public

functions must make themselves

available to everyone, regardless

of personal creed for example,

an airport taxi driver must pick

up passengers carrying duty-free

alcohol even if he or she deems

drinking to be sinful.2 The competition for the public space and

the question of who may be

forced to make some sacrifice

was captured well by Florida Senator Marco Rubio, who argued

that the government cant force

religious organizations to abandon the fundamental tenets of

their faith. . . . If an employee

wants birth control, that worker

could . . . just choose to work

elsewhere.3

Similar reasoning underlies

many arguments for the acceptability of service denials: the patient should simply go elsewhere.

But it is far from a solution when

sectarian-hospital emergency departments refuse to provide

emergency contraception to rape

victims or to perform health-preserving surgeries after incomplete miscarriages. In the past

decade, religiously affiliated orga-

Contraceptive Drugs may cause political headaches

nizations owned nearly one in five

U.S. hospital beds,4 and doctrinal

restrictions at secular hospitals

are growing because of increasing mergers with religious hospital systems.5 A vision of a public space in which every religious

practice blooms might quickly

become one in which a single religious doctrine is imposed.

Institutions opposing the new

policy argue that theyre still financially connected to the contraceptive benefit, in contradiction

to their doctrine. But Americans

dont usually succeed in claims

that the use of their funds in

tional doctrine could be withheld including, it would seem,

ordinary salary.

Given the lack of past controversy over state laws on contraceptive insurance coverage and

the spate of recent efforts to constrict reproductive rights ranging from personhood amendments granting fertilized eggs

the same legal rights as liveborn

children, to mandatory transvaginal ultrasonography before consenting to an abortion, to the

defunding of screening for cancer and sexually transmitted diseases at organizations that sepa-

Some argue that when services are denied,

patients can simply go elsewhere.

But its far from a solution when

sectarian-hospital emergency departments

refuse to provide emergency contraception to

rape victims or to perform health-preserving

surgeries after incomplete miscarriages.

contravention of their religious

views violates their constitutional

or statutory rights: tax resisters,

for instance, have been swatted

down by the courts, even when

they were objecting to state-

ordered killing in the form of

capital punishment or war. And

the objections in this instance are

yet more tenuous: Catholic hospitals and universities are not required to pay for birth-control

coverage. Nonetheless, coverage

in the general benefit package is

considered unacceptable complicity. By this logic, any benefit that

an employee might use to commit an act contrary to institu-

rately provide privately funded

abortion services some observers characterize the debate

over contraceptive coverage as a

war on women. But others point

to litigation about prayer in

schools, Christmas displays on

public lands, and requiring U.S.

aid organizations to offer contraceptive services to rape victims

in war zones as evidence of a war

on religion.

Lets recognize that the current debate is about public health

and contraception. But at the same

time, given the battle over framing, lets also take seriously the

more enduring question about our

n engl j med 366;15 nejm.org april 12, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 19, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1363

PERSPE C T I V E

Contraceptive Drugs may cause political headaches

public space: whether every religious institution and adherent is

free to act to the point of imposing on others, or whether every

individual is free from being imposed upon to the point of stifling some who would act. This

debate deserves more than partisan sound bites and slogans. Perhaps Friess wasnt too far off,

and the best cure for todays contraceptive headache is for the entire country to take two aspirin

and lay off until after the election.

Disclosure forms provided by the author

are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

From the School of Law and the School of

Medicine and Public Health, University of

Wisconsin, Madison.

This article (10.1056/NEJMp1202701) was

published on March 14, 2012, at NEJM.org.

1. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Decision on contraception (http://www

.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/decision-contraception

.html).

2. Charo RA. Health care provider refusals

to treat, prescribe, refer or inform: profes-

sionalism and conscience. Washington, DC:

American Constitution Society for Law and

Policy, 2007 (http://www.acslaw.org/sites/

default/files/Charo_-_Health_Care_Refusals

.pdf).

3. Bolstad E. Floridas Rubio pushes back at

contraception rules under health care law.

McClatchy Newspapers Washington Bureau.

February 5, 2012.

4. Uttley L, Pawelko R. No strings attached:

public funding of religiously-sponsored hospitals in the United States. MergerWatch

Project, 2002 (http://www.mergerwatch.org/

mergerwatch-publications).

5. Abelson R. Catholic hospitals expand, religious strings attached. New York Times.

February 20, 2012:A1.

Copyright 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Medicares Readmissions-Reduction Program

A Positive Alternative

Robert A. Berenson, M.D., Ronald A. Paulus, M.D., M.B.A., and Noah S. Kalman, B.A.

ospital readmissions are receiving increasing attention

as a largely correctable source of

poor quality of care and excessive spending. According to a 2009

study, nearly 20% of Medicare

beneficiaries are rehospitalized

within 30 days after discharge,

at an annual cost of $17 billion.1

Causes of avoidable readmissions

include hospital-acquired infections and other complications;

premature discharge; failure to

coordinate and reconcile medications; inadequate communication

among hospital personnel, patients, caregivers, and communitybased clinicians; and poor planning for care transitions.

Although studies have shown

that specific interventions, particularly among patients with

multiple medical conditions, can

reduce readmission rates by 25 to

50%,2 the Centers for Medicare

and Medicaid Services (CMS)

found that Medicares national

1364

30-day readmission rate did not

change appreciably between 2004

and 2009. Unless they are at full

capacity, hospitals have no economic incentive to reduce readmissions under Medicares diagnosisrelated group (DRG) payment

approach. The Affordable Care

Act (ACA) therefore created a financial penalty for excessive

readmissions at hospitals that

are paid for DRGs. Unfortunately,

this approach may be too weak

to overcome the substantial counterincentives inherent in DRGbased payments It also tries to

change hospitals behavior with

a stick but no carrot, failing to

reward hospitals that improve.

We propose an alternative approach a warranty payment

that provides a stronger business case for hospitals to get

with the program.

Under the ACA, CMS calculates the average risk-adjusted,

30-day hospital-readmission rates

for patients with myocardial infarction, pneumonia, or heart failure using claims data. If a hospitals risk-adjusted readmission rate

for such patients exceeds that average, CMS penalizes it in the

following year for all Medicare

admissions in proportion to its

rate of excess rehospitalizations

of patients for the target conditions. Although the maximum

penalty is set at 1% for 2013,

eventually reaching 3% of a hospitals Medicare payments, the

CMS implementation reduces the

potential penalties in aggregate

to only 0.2% of national Medicare

payments in 2013.3 Payments for

hospitals with below-average rehospitalization rates for all three

conditions wont change. Eventually, CMS plans to expand this

program to include other common diagnoses for which readmissions are theoretically preventable, boosting the financial

effects.

n engl j med 366;15 nejm.org april 12, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 19, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Universal Medical Care from Conception to End of Life: The Case for A Single-Payer SystemFrom EverandUniversal Medical Care from Conception to End of Life: The Case for A Single-Payer SystemNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Cure: Review and Analysis of David Gratzer's BookFrom EverandSummary: The Cure: Review and Analysis of David Gratzer's BookNo ratings yet

- Living in the Shadow of Blackness as a Black Physician and Healthcare Disparity in the United States of AmericaFrom EverandLiving in the Shadow of Blackness as a Black Physician and Healthcare Disparity in the United States of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Summary: Landmark: Review and Analysis of The Washington Post's BookFrom EverandSummary: Landmark: Review and Analysis of The Washington Post's BookNo ratings yet

- Health Care Disparity in the United States of AmericaFrom EverandHealth Care Disparity in the United States of AmericaRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The New HHS Rule of The Trump Administration The Trump AdministrationDocument10 pagesThe New HHS Rule of The Trump Administration The Trump Administrationapi-543685144No ratings yet

- Is Healthcare A Right or A PrivilegeDocument6 pagesIs Healthcare A Right or A Privilegearies usamaNo ratings yet

- Priceless: Curing the Healthcare CrisisFrom EverandPriceless: Curing the Healthcare CrisisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- 2012-06-19 - BPCLC Comments On Contraceptive Coverage For ANPRMDocument3 pages2012-06-19 - BPCLC Comments On Contraceptive Coverage For ANPRMState Senator Liz KruegerNo ratings yet

- Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930From EverandHealth Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- How Public Health Approach To Obesogenic Environments Decrease Rates of Chronic Disease - EditedDocument8 pagesHow Public Health Approach To Obesogenic Environments Decrease Rates of Chronic Disease - Editedkelvin karengaNo ratings yet

- Association of Schools of Public HealthDocument8 pagesAssociation of Schools of Public HealthduckythiefNo ratings yet

- Letter To NIH 10-13-15Document3 pagesLetter To NIH 10-13-15ElDisenso.comNo ratings yet

- Fighting For SurvivalDocument6 pagesFighting For SurvivalCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Health Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceFrom EverandHealth Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Reforming America's Health Care System: The Flawed Vision of ObamaCareFrom EverandReforming America's Health Care System: The Flawed Vision of ObamaCareRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Defend Yourself!: How to Protect Your Health, Your Money, And Your Rights in 10 Key Areas of Your LifeFrom EverandDefend Yourself!: How to Protect Your Health, Your Money, And Your Rights in 10 Key Areas of Your LifeNo ratings yet

- Us Healthcare SystemDocument20 pagesUs Healthcare SystemGrahame EvansNo ratings yet

- Health Care Backgrounder Abortion 2009 07 17Document2 pagesHealth Care Backgrounder Abortion 2009 07 17Martin, Trisha Mae M. HUMSS-8No ratings yet

- Perspective: New England Journal MedicineDocument3 pagesPerspective: New England Journal MedicineKevin HolmesNo ratings yet

- The Argumentative Essay: Health Care in AmericaDocument10 pagesThe Argumentative Essay: Health Care in AmericaRosana Cook-PowellNo ratings yet

- Doctors, Hospitals, Insurers, Oh My! What You Need to know about Health Insurance and Health CareFrom EverandDoctors, Hospitals, Insurers, Oh My! What You Need to know about Health Insurance and Health CareNo ratings yet

- Walker Style DraftDocument11 pagesWalker Style Draftapi-437845987No ratings yet

- It’s All About Money and Politics: Winning the Healthcare War: Your Guide to Healthcare ReformFrom EverandIt’s All About Money and Politics: Winning the Healthcare War: Your Guide to Healthcare ReformNo ratings yet

- The Raging War On Vaccine Choice, Barbara Loe Fisher, NVICDocument3 pagesThe Raging War On Vaccine Choice, Barbara Loe Fisher, NVICCaroline HawksNo ratings yet

- HCA434 Current Event PaperDocument5 pagesHCA434 Current Event PaperAlvin ManiagoNo ratings yet

- Dying For CoverageDocument6 pagesDying For Coverageapi-608060711No ratings yet

- Policiy Issue StatementDocument5 pagesPoliciy Issue StatementRicky DavisNo ratings yet

- Policiy Issue StatementDocument5 pagesPoliciy Issue StatementRicky DavisNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Autonomy and Informed Consent: Ethic Theory Moral Prac (2016) 19:225 - 244 DOI 10.1007/s10677-015-9610-8Document20 pagesObstetric Autonomy and Informed Consent: Ethic Theory Moral Prac (2016) 19:225 - 244 DOI 10.1007/s10677-015-9610-8Sindy Amalia FNo ratings yet

- RoevWade FDocument6 pagesRoevWade Fzeinab mawlaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Mandatory VaccinesDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Mandatory Vaccinesapi-569130786No ratings yet

- Curing Medicare: A Doctor's View on How Our Health Care System Is Failing Older Americans and How We Can Fix ItFrom EverandCuring Medicare: A Doctor's View on How Our Health Care System Is Failing Older Americans and How We Can Fix ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Vaccine Peer Review 1000 PDFDocument1,053 pagesVaccine Peer Review 1000 PDFJeffPrager100% (3)

- Abortion Rights - Judicial History and Legislative Battle in the United StatesFrom EverandAbortion Rights - Judicial History and Legislative Battle in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- A Cure For The Incurable?: Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted SuicideDocument8 pagesA Cure For The Incurable?: Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicideapi-355913378No ratings yet

- STAT News - The ADA Covers Addiction. Now The U.S. Is Enforcing The Law (To Protect Former Addicts) - STATDocument13 pagesSTAT News - The ADA Covers Addiction. Now The U.S. Is Enforcing The Law (To Protect Former Addicts) - STATKirk HartleyNo ratings yet

- The History of Abortion Legislation in the USA: Judicial History and Legislative ResponseFrom EverandThe History of Abortion Legislation in the USA: Judicial History and Legislative ResponseNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Rights of Conscience: Defending Life 2010Document26 pagesHealthcare Rights of Conscience: Defending Life 2010campsolaulNo ratings yet

- HEADLINE: Health Economics 101 BYLINE: by Paul Krugman Bob Herbert Is On Vacation. BodyDocument8 pagesHEADLINE: Health Economics 101 BYLINE: by Paul Krugman Bob Herbert Is On Vacation. BodyJohn_Lee_8554No ratings yet

- Universal Health Care in The Us 1Document6 pagesUniversal Health Care in The Us 1api-608060711No ratings yet

- Abortion in the United States - Judicial History and Legislative BattleFrom EverandAbortion in the United States - Judicial History and Legislative BattleNo ratings yet

- Mercola: How To Legally Get A Vaccine ExemptionDocument7 pagesMercola: How To Legally Get A Vaccine ExemptionJonathan Robert Kraus (OutofMudProductions)100% (1)

- Open Letter On FDA and AidAccessDocument5 pagesOpen Letter On FDA and AidAccessGMG EditorialNo ratings yet

- Αυξάνονται ανησυχητικά οι νόμοι κατά των αμβλώσεων παρατηρεί αμερικανική ΜΚΟDocument12 pagesΑυξάνονται ανησυχητικά οι νόμοι κατά των αμβλώσεων παρατηρεί αμερικανική ΜΚΟLawNetNo ratings yet

- Universal Health CareDocument8 pagesUniversal Health CarekevinNo ratings yet

- Senior Project Essay - Noah ParkDocument15 pagesSenior Project Essay - Noah Parkapi-668813575No ratings yet

- The Right To Health, by Thomas SzaszDocument11 pagesThe Right To Health, by Thomas SzaszNicolas Martin0% (1)

- Module Two 1Document3 pagesModule Two 1api-612975585No ratings yet

- Literature Review - Jacob HaireDocument8 pagesLiterature Review - Jacob Haireapi-609397927No ratings yet

- Universal HealthcareDocument6 pagesUniversal HealthcareKarmen AliNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Should Welfare Applicants Be Drug Tested 1Document6 pagesRunning Head: Should Welfare Applicants Be Drug Tested 1Adroit WriterNo ratings yet

- TennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionFrom EverandTennCare, One State's Experiment with Medicaid ExpansionNo ratings yet

- Hi 225 FinalpaperDocument11 pagesHi 225 Finalpaperapi-708689221No ratings yet

- Cesaire A TempestDocument40 pagesCesaire A TempestJosef Yusuf100% (3)

- View of Hebrews Ethan SmithDocument295 pagesView of Hebrews Ethan SmithOlvin Steve Rosales MenjivarNo ratings yet

- 21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 40, OcrDocument60 pages21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 40, OcrJapanAirRaids80% (5)

- This Is My Beloved Son Lesson PlanDocument1 pageThis Is My Beloved Son Lesson PlancamigirlutNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of The Payment of Wages ActDocument2 pagesCritical Analysis of The Payment of Wages ActVishwesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources: Niño E. Dizor Riza Mae Dela CruzDocument8 pagesDepartment of Environment and Natural Resources: Niño E. Dizor Riza Mae Dela CruzNiño Esco DizorNo ratings yet

- ET Banking & FinanceDocument35 pagesET Banking & FinanceSunchit SethiNo ratings yet

- MONITORING Form LRCP Catch UpDocument2 pagesMONITORING Form LRCP Catch Upramel i valenciaNo ratings yet

- English Humorists of The Eighteenth Century. ThackerayDocument280 pagesEnglish Humorists of The Eighteenth Century. ThackerayFlaviospinettaNo ratings yet

- Bow IwrbsDocument4 pagesBow IwrbsRhenn Bagtas SongcoNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Human Geography PDFDocument2 pagesEncyclopedia of Human Geography PDFRosi Seventina100% (1)

- Water Conference InvitationDocument2 pagesWater Conference InvitationDonna MelgarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On RapunzelDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On RapunzelfvgcaatdNo ratings yet

- Qualitative KPIDocument7 pagesQualitative KPIMas AgusNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - Bank ReconciliationDocument29 pagesChapter 12 - Bank Reconciliationshemida100% (7)

- A Review On The Political Awareness of Senior High School Students of St. Paul University ManilaDocument34 pagesA Review On The Political Awareness of Senior High School Students of St. Paul University ManilaAloisia Rem RoxasNo ratings yet

- Police Information Part 8Document8 pagesPolice Information Part 8Mariemel EsparagozaNo ratings yet

- Senior Residents & Senior Demonstrators - Annexure 1 & IIDocument3 pagesSenior Residents & Senior Demonstrators - Annexure 1 & IIsarath6872No ratings yet

- Bhagwanti's Resume (1) - 2Document1 pageBhagwanti's Resume (1) - 2muski rajputNo ratings yet

- B16. Project Employment - Bajaro vs. Metro Stonerich Corp.Document5 pagesB16. Project Employment - Bajaro vs. Metro Stonerich Corp.Lojo PiloNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument256 pagesUntitledErick RomeroNo ratings yet

- 4 Marine Insurance 10-8-6Document53 pages4 Marine Insurance 10-8-6Eunice Saavedra100% (1)

- Excerpted From Watching FoodDocument4 pagesExcerpted From Watching Foodsoc2003No ratings yet

- Um Tagum CollegeDocument12 pagesUm Tagum Collegeneil0522No ratings yet

- Christmas Phrasal VerbsDocument2 pagesChristmas Phrasal VerbsannaNo ratings yet

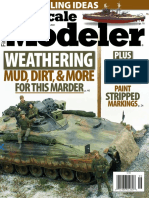

- FineScale Modeler - September 2021Document60 pagesFineScale Modeler - September 2021Vasile Pop100% (2)

- Problem Set 2Document2 pagesProblem Set 2nskabra0% (1)

- Glossary of Fashion Terms: Powered by Mambo Generated: 7 October, 2009, 00:47Document4 pagesGlossary of Fashion Terms: Powered by Mambo Generated: 7 October, 2009, 00:47Chetna Shetty DikkarNo ratings yet

- (FINA1303) (2014) (F) Midterm Yq5j8 42714Document19 pages(FINA1303) (2014) (F) Midterm Yq5j8 42714sarah shanNo ratings yet