Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Leads & Lanes

Uploaded by

bhabhasunil0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views3 pagesNavigating safely through ice requires careful planning and decision making. When approaching ice, it is often better to go around rather than through if the ice is dense. If entering ice is necessary, the distribution and conditions of the ice should be thoroughly examined from high elevation or aircraft to identify navigable routes like leads and polynyas. Once in the ice, proceed slowly at first and maneuver to stay in open water or weak ice areas, increasing speed only after determining how the vessel handles under different ice conditions. Quick maneuvering may be needed if conditions change rapidly, so vessels should attempt to navigate leads and avoid contact with thick floes whenever possible.

Original Description:

Navigating in Ice through leads & lanes

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNavigating safely through ice requires careful planning and decision making. When approaching ice, it is often better to go around rather than through if the ice is dense. If entering ice is necessary, the distribution and conditions of the ice should be thoroughly examined from high elevation or aircraft to identify navigable routes like leads and polynyas. Once in the ice, proceed slowly at first and maneuver to stay in open water or weak ice areas, increasing speed only after determining how the vessel handles under different ice conditions. Quick maneuvering may be needed if conditions change rapidly, so vessels should attempt to navigate leads and avoid contact with thick floes whenever possible.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views3 pagesLeads & Lanes

Uploaded by

bhabhasunilNavigating safely through ice requires careful planning and decision making. When approaching ice, it is often better to go around rather than through if the ice is dense. If entering ice is necessary, the distribution and conditions of the ice should be thoroughly examined from high elevation or aircraft to identify navigable routes like leads and polynyas. Once in the ice, proceed slowly at first and maneuver to stay in open water or weak ice areas, increasing speed only after determining how the vessel handles under different ice conditions. Quick maneuvering may be needed if conditions change rapidly, so vessels should attempt to navigate leads and avoid contact with thick floes whenever possible.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

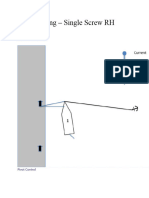

Navigating in Ice Through Leads & Lanes

Compiled By: Capt Sunil Bhabha

Source: Various & from Internet

Last Reviewed: 1st April 2015

Upon the approach to pack ice, a careful decision is needed to determine the best

action. Often it is possible to go around the ice, rather than through it. Unless the

pack is quite loose, this action usually gains rather than loses time. When skirting

an ice field or an iceberg, do so to windward, if a choice is available, to avoid

projecting tongues of ice or individual pieces that have been blown away from the

main body of ice.

When it becomes necessary to enter pack ice, a thorough examination of the

distribution and extent of the ice conditions should be made beforehand from the

highest possible location. Aircraft (particularly helicopters) and direct satellite

readouts are of great value in determining the nature of the ice to be encountered.

The most important features to be noted include the location of open water, such as

leads and polynyas (A polynya is an area of open water surrounded by sea ice. It is

now used as geographical term for an area of unfrozen sea within the ice pack),

which may be manifested by water sky (Water sky is a phenomenon that is closely

related to ice blink. It forms in regions with large areas of ice and low lying clouds

and so is limited mostly to the extreme northern and southern sections of earth,

in Antarctica and in the Arctic); icebergs; and the presence or absence of both ice

under pressure and rotten ice.

Some protection may be offered the propeller and rudder assemblies by trimming

the vessel down by the stern slightly (not more than 23 feet) prior to entering the

ice; however, this precaution usually impairs the maneuvering characteristics of

most vessels not specifically built for ice breaking.

Selecting the point of entry into the pack should be done with great care; and if the

ice boundary consists of closely packed ice or ice under pressure, it is advisable to

skirt the edge until a more desirable point of entry is located. Seek areas with low

ice concentrations, areas of rotten ice or those containing navigable leads, and if

possible enter from leeward on a course perpendicular to the ice edge. It is also

advisable to take into consideration the direction and force of the wind, and the set

and drift of the prevailing currents when determining the point of entry and the

course followed thereafter.

Due to wind induced wave action, ice floes close to the periphery of the ice pack

will take on a bouncing motion which can be quite hazardous to the hull of thin

skinned vessels. In addition, note that pack ice will drift slightly to the right of the

true wind in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere,

and that leads opened by the force of the wind will appear perpendicular to the

wind direction. If a suitable entry point cannot be located due to less than favorable

conditions, patience may be called for. Unfavorable conditions generally improve

over a short period of time by a change in the wind, tide, or sea state.

Once in the pack, always try to work with the ice, not against it, and keep moving,

but do not rush. Respect the ice but do not fear it. Proceed at slow speed at first,

staying in open water or in areas of weak ice if possible. The vessels speed may be

safely increased after it has been ascertained how well it handles under the varying

Capt Sunil Bhabha

Page 1

ice conditions encountered. It is better to make good progress in the general

direction desired than to fight large thick floes in the exact direction to be made

good. However, avoid the temptation to proceed far to one side of the intended

track; it is almost always better to back out and seek a more penetrable area.

During those situations when it becomes necessary to back, always do so with

extreme caution and with the rudder amidships.

If the ship is stopped by ice, the first command should be rudder amidships, given

while the screw is still turning. This will help protect the propeller when backing and

prevent ice jamming between rudder and hull. If the rudder becomes ice-jammed,

man after steering, establish communications, and do not give any helm commands

until the rudder is clear. A quick full-ahead burst may clear it. If it does not, try

going to hard rudder in the same direction slowly while turning full or flank speed

ahead.

Ice conditions may change rapidly while a vessel is working in pack ice,

necessitating quick maneuvering. Conventional vessels, even if ice strengthened,

are not built for ice breaking. The vessel should be conned to first attempt to place

it in leads or polynyas, giving due consideration to wind conditions. The age,

thickness, and size of ice which can be navigated depend upon the type, size, hull

strength, and horsepower of the vessel employed.

If contact with an ice floe is unavoidable, never strike it a glancing blow. This

maneuver may cause the ship to veer off in a direction which will swing the stern

into the ice. If possible, seek weak spots in the floe and hit it head-on at slow speed.

Unless the ice is rotten or very young, do not attempt to break through the floe, but

rather make an attempt to swing it aside as speed is slowly increased. Keep clear of

corners and projecting points of ice, but do so without making sharp turns which

may throw the stern against the ice, resulting in a damaged propeller, propeller

shaft, or rudder. The use of full rudder in non-emergency situations is not

recommended because it may swing either the stern or mid-section of the vessel

into the ice. This does not preclude use of alternating full rudder (swinging the

rudder) aboard ice-breakers as a technique for penetrating heavy ice.

Offshore winds may open relatively ice free navigable coastal leads, but such leads

should not be entered without benefit of icebreaker escort. If it becomes necessary

to enter coastal leads, narrow straits, or bays, an alert watch should be maintained

since a shift in the wind may force drifting ice down upon the vessel. An increase in

wind on the windward side of a prominent point, grounded iceberg, or land ice

tongue extending into the sea will also endanger a vessel. It is wiser to seek out

leads toward the windward side of the main body of the ice pack.

In the event that the vessel is under imminent danger of being trapped close to

shore by pack ice, immediately attempt to orient the vessels bow seaward. This will

help to take advantage of the little maneuvering room available in the open water

areas found between ice floes. Work carefully through these areas, easing the ice

floes aside while maintaining a close watch on the general movement of the ice

pack.

Capt Sunil Bhabha

Page 2

Capt Sunil Bhabha

Page 3

You might also like

- 5 Important Points For Ice Navigation of ShipsDocument6 pages5 Important Points For Ice Navigation of ShipscassandraNo ratings yet

- The Island Hopping Digital Guide To The Northern Bahamas - Part II - The Biminis and the Berry Islands: Including Information on Crossing the Gulf Stream and the Great Bahama BankFrom EverandThe Island Hopping Digital Guide To The Northern Bahamas - Part II - The Biminis and the Berry Islands: Including Information on Crossing the Gulf Stream and the Great Bahama BankNo ratings yet

- Navigation in IceDocument8 pagesNavigation in IceAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- The Hazards of Ice TSCL 2-2003 PDFDocument2 pagesThe Hazards of Ice TSCL 2-2003 PDFClarence PieterszNo ratings yet

- Explain With The Help of Suitable Diagram, The Sequential Formation of Sea IceDocument6 pagesExplain With The Help of Suitable Diagram, The Sequential Formation of Sea IceRagunath Ramasamy100% (1)

- Trainee Manual - ICE NavigationDocument46 pagesTrainee Manual - ICE NavigationBirlic AdrianNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Ice NavigationDocument24 pagesIntroduction To Ice Navigationgeims11No ratings yet

- Antarctica EnglishDocument63 pagesAntarctica EnglishLove-Gay RaguntonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Ice Navigation PDFDocument24 pagesIntroduction To Ice Navigation PDFMarijaŽaper100% (2)

- Re-Float A Grounded VesselDocument6 pagesRe-Float A Grounded Vesseldeniyuni86No ratings yet

- Midterm Topic in Meteorology 2: Pedroso, Ryan Benedict I. BSMT 2-HotelDocument11 pagesMidterm Topic in Meteorology 2: Pedroso, Ryan Benedict I. BSMT 2-HotelRyan BenedictNo ratings yet

- Ice NavigationDocument28 pagesIce NavigationgeorgesagunaNo ratings yet

- Ice Navigation: Ice Navigation in Theory Ice Navigation in PracticeDocument18 pagesIce Navigation: Ice Navigation in Theory Ice Navigation in PracticeIban Santana HernandezNo ratings yet

- Macgregor 26 MDocument28 pagesMacgregor 26 MRyan Carter100% (1)

- J. 2019 Bowditch - Volume 1 - Part 8 Ice and Polar Navigation Chapter 32-33Document57 pagesJ. 2019 Bowditch - Volume 1 - Part 8 Ice and Polar Navigation Chapter 32-33Sydney HansonNo ratings yet

- Navigation in Special ConditionsDocument10 pagesNavigation in Special ConditionsoLoLoss mNo ratings yet

- Ships & Ice: Notes On Ice NavigationDocument14 pagesShips & Ice: Notes On Ice NavigationbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Sailing Manual IntermediateDocument22 pagesSailing Manual IntermediateEmilNo ratings yet

- Ice AccretionDocument2 pagesIce AccretionManishNo ratings yet

- 1MFG Function 1Document176 pages1MFG Function 1Rohit RajNo ratings yet

- Cold Weather NavigationDocument8 pagesCold Weather NavigationDujeKnezevicNo ratings yet

- Ice at Sea PDFDocument14 pagesIce at Sea PDFRagunath RamasamyNo ratings yet

- Masters Check ListDocument1 pageMasters Check ListEMRECAN KIVANÇNo ratings yet

- Manoeuvring The Vessels in Heavy Weather at SeaDocument7 pagesManoeuvring The Vessels in Heavy Weather at SeaMahesh Poonia100% (5)

- CAP - Stranding BeachingDocument14 pagesCAP - Stranding BeachingChristopherNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Anchoring PDFDocument18 pagesUnit 1 - Anchoring PDFClaudiuAlex100% (1)

- Who Needs To Winterize?: Distributed in Partnership WithDocument12 pagesWho Needs To Winterize?: Distributed in Partnership WithAbigail JohnsonNo ratings yet

- FONACIER, HAROLD M. Assign-No.2Document3 pagesFONACIER, HAROLD M. Assign-No.2Ironman SpongebobNo ratings yet

- 5 - Ice Navigation - UnassistedDocument19 pages5 - Ice Navigation - Unassistedmixailus2735No ratings yet

- Ice On ShipsDocument2 pagesIce On ShipsSai SahNo ratings yet

- UndockingDocument10 pagesUndockingAurelio DutariNo ratings yet

- Owner'S Instructions Macgregor 26 M: Special Safety WarningsDocument28 pagesOwner'S Instructions Macgregor 26 M: Special Safety WarningsPedroNo ratings yet

- Words of Wisdom With Conner Blouin Downwind Sunfish SailingDocument8 pagesWords of Wisdom With Conner Blouin Downwind Sunfish SailingJamesNo ratings yet

- Drift Ice: See AlsoDocument2 pagesDrift Ice: See AlsoIngbor99No ratings yet

- Glaciers and GlaciationDocument2 pagesGlaciers and GlaciationVera BalmesNo ratings yet

- Sea Ice: Fast Ice Versus Drift (Or Pack) IceDocument9 pagesSea Ice: Fast Ice Versus Drift (Or Pack) IceIngbor99No ratings yet

- 5 Ice On SeaDocument24 pages5 Ice On SeaMD hidtzNo ratings yet

- Manoevuring Vessel in EmergencyDocument2 pagesManoevuring Vessel in EmergencyArun VargheseNo ratings yet

- Vego - SSKs and Shallow Water ASWDocument7 pagesVego - SSKs and Shallow Water ASWDMNo ratings yet

- Aastmt: Ali Abd Alrahman 1 8 2 0 0 5 3 3 Term 4 Ship HandlingDocument3 pagesAastmt: Ali Abd Alrahman 1 8 2 0 0 5 3 3 Term 4 Ship Handlingعلي عبد الرحمن الزيديNo ratings yet

- B I HE KEY Stages IN THE Formation OF SEA ICE Until IT IS ONE Year OLD SEA ICEDocument5 pagesB I HE KEY Stages IN THE Formation OF SEA ICE Until IT IS ONE Year OLD SEA ICERigel NathNo ratings yet

- Prep For Heavy WXDocument2 pagesPrep For Heavy WXDee CeeNo ratings yet

- Oil and Gas Offshore ProductionDocument9 pagesOil and Gas Offshore ProductionLao ZhuNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Maneuver To Turn A ShipDocument5 pagesWeek 7 Maneuver To Turn A Shipacostaflorencemay13No ratings yet

- Good Slipway DesignDocument4 pagesGood Slipway Designbeddows_s100% (1)

- Rolling in Following Seas - BoatTEST - Com - Printer FriendlyDocument1 pageRolling in Following Seas - BoatTEST - Com - Printer FriendlyAlex MilarNo ratings yet

- ANCSYSENG002Document8 pagesANCSYSENG002Tom MoritzNo ratings yet

- AnchoringDocument12 pagesAnchoringDryanmNo ratings yet

- The Basic of Dive Operations Within CurrentsDocument3 pagesThe Basic of Dive Operations Within CurrentsdivermedicNo ratings yet

- Anchoring: Factors To Bear in Mind While Determining Safe Anchorage / Anchor PlanningDocument39 pagesAnchoring: Factors To Bear in Mind While Determining Safe Anchorage / Anchor Planningmaneesh0% (1)

- Dry Docking OperationsDocument5 pagesDry Docking Operationshutsonianp100% (2)

- Know The Rules: Safe SpeedDocument6 pagesKnow The Rules: Safe SpeedSandy BhattiNo ratings yet

- Ice at SeaDocument8 pagesIce at SeaReuben EphraimNo ratings yet

- The Basics of Sailing: HobieDocument15 pagesThe Basics of Sailing: HobieNey GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Ship HandlingDocument43 pagesShip HandlingSyamesh SeaNo ratings yet

- How To Navigate A ShipDocument2 pagesHow To Navigate A ShipJovie Ann RamiloNo ratings yet

- Stability AssignmentDocument8 pagesStability Assignmentel pinkoNo ratings yet

- All Thousand Islands Routes - 0Document53 pagesAll Thousand Islands Routes - 0jgrzadka2No ratings yet

- Glacier Course MIT Earthsurface 7Document81 pagesGlacier Course MIT Earthsurface 7Iván Cáceres AnguloNo ratings yet

- 2020 10 Matching Photo E - GovernanceDocument3 pages2020 10 Matching Photo E - GovernancebhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- High Latitudes Navigation PDFDocument5 pagesHigh Latitudes Navigation PDFbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- 2020 12 Examination ScheduleDocument1 page2020 12 Examination SchedulebhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- 2020 11 MEDICARE MFA Refresher Not MandatoryDocument1 page2020 11 MEDICARE MFA Refresher Not MandatorybhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- 2020 06 Batch NumberingDocument5 pages2020 06 Batch NumberingbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Bridge Alert Management PDFDocument18 pagesBridge Alert Management PDFbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Phosphoric AcidDocument2 pagesPhosphoric AcidbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Ships & Ice: Notes On Ice NavigationDocument14 pagesShips & Ice: Notes On Ice NavigationbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Using Previous Years AlmanacDocument1 pageUsing Previous Years AlmanacbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Gdop NotesDocument3 pagesGdop NotesbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- CoF Vs NLSDocument4 pagesCoF Vs NLSbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- CoF Vs NLSDocument4 pagesCoF Vs NLSbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Limitation of Liability For Maritime ClaimsDocument3 pagesLimitation of Liability For Maritime ClaimsbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- Limitation of Liability For Maritime ClaimsDocument3 pagesLimitation of Liability For Maritime ClaimsbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- PS For AisDocument4 pagesPS For AisbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- SRSDocument4 pagesSRSbhabhasunilNo ratings yet

- GP150 PDFDocument125 pagesGP150 PDFBf Ipanema100% (1)

- Deposition and Characterization of Copper Oxide Thin FilmsDocument5 pagesDeposition and Characterization of Copper Oxide Thin FilmsmirelamanteamirelaNo ratings yet

- Old Zigzag Road FinalDocument3 pagesOld Zigzag Road FinalAlex PinlacNo ratings yet

- Reheating and Preheating After Inflation: An IntroductionDocument9 pagesReheating and Preheating After Inflation: An IntroductionSourav GopeNo ratings yet

- Study On Causes & Control of Cracks in A Structure: Mulla FayazDocument4 pagesStudy On Causes & Control of Cracks in A Structure: Mulla FayazShubham ThakurNo ratings yet

- CEP Presentation AOL 2023Document143 pagesCEP Presentation AOL 2023Josh DezNo ratings yet

- Iron Ore Value-In-Use: Benchmarking and Application: Peter Hannah AnalystDocument19 pagesIron Ore Value-In-Use: Benchmarking and Application: Peter Hannah AnalystAnkit BansalNo ratings yet

- Fields and Galois Theory: J.S. MilneDocument138 pagesFields and Galois Theory: J.S. MilneUzoma Nnaemeka TeflondonNo ratings yet

- Emu ManualDocument86 pagesEmu ManualMiguel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Istambul TurciaDocument2 pagesIstambul Turciaantoneacsabin06No ratings yet

- 01-CPD-8, Civil Aviation Procedure Document On Airworthiness-MinDocument884 pages01-CPD-8, Civil Aviation Procedure Document On Airworthiness-Minnishat529100% (1)

- Geometri Unsur StrukturDocument10 pagesGeometri Unsur StrukturNirmaya WulandariNo ratings yet

- Leaked New Zealand Health Data Had The Government Told The Truth About Vaccine Harms Lives Would HaveDocument8 pagesLeaked New Zealand Health Data Had The Government Told The Truth About Vaccine Harms Lives Would HavemikeNo ratings yet

- Souvenir As Tourism ProductDocument13 pagesSouvenir As Tourism ProductThree Dimensional Product DesignNo ratings yet

- The 5-Phase New Pentagon Driver Chip Set: 1. Excitation Sequence GeneratorDocument11 pagesThe 5-Phase New Pentagon Driver Chip Set: 1. Excitation Sequence GeneratorFreddy MartinezNo ratings yet

- Death There Mirth Way The Noisy Merit.Document2 pagesDeath There Mirth Way The Noisy Merit.Kristen DukeNo ratings yet

- Scribe Edu DatasheetDocument4 pagesScribe Edu DatasheetG & M Soft Technologies Pvt LtdNo ratings yet

- TRIAS - Master ProposalDocument12 pagesTRIAS - Master ProposalHafidGaneshaSecretrdreamholicNo ratings yet

- Gs Reported Speech - ExercisesDocument6 pagesGs Reported Speech - ExercisesRamona FloreaNo ratings yet

- Thermostability of PVC and Related Chlorinated Polymers: Application Bulletin 205/2 eDocument3 pagesThermostability of PVC and Related Chlorinated Polymers: Application Bulletin 205/2 eAnas ImdadNo ratings yet

- Iot Based Home Automation Using NodemcuDocument52 pagesIot Based Home Automation Using NodemcuSyed ArefinNo ratings yet

- Retscreen International: Clean Energy Project AnalysisDocument72 pagesRetscreen International: Clean Energy Project AnalysisAatir SalmanNo ratings yet

- Govt. College of Nusing C.R.P. Line Indore (M.P.) : Subject-Advanced Nursing PracticeDocument17 pagesGovt. College of Nusing C.R.P. Line Indore (M.P.) : Subject-Advanced Nursing PracticeMamta YadavNo ratings yet

- UA&P-JD Application FormDocument4 pagesUA&P-JD Application FormuapslgNo ratings yet

- Topic: Atoms and Molecules Sub-Topic: Mole: Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesTopic: Atoms and Molecules Sub-Topic: Mole: Lesson PlanPushpa Kumari67% (3)

- Final Coaching - FundaDocument3 pagesFinal Coaching - FundaenzoNo ratings yet

- Designation Order SicDocument3 pagesDesignation Order SicMerafe Ebreo AluanNo ratings yet

- Architechture of 8086 or Functional Block Diagram of 8086 PDFDocument3 pagesArchitechture of 8086 or Functional Block Diagram of 8086 PDFAdaikkal U Kumar100% (2)

- Indian Participation in CERN Accelerator ProgrammesDocument54 pagesIndian Participation in CERN Accelerator ProgrammesLuptonga100% (1)

- À Bout de Souffle (Breathless) : Treatment by François TruffautDocument10 pagesÀ Bout de Souffle (Breathless) : Treatment by François TruffautAlex KahnNo ratings yet

- Strong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerFrom EverandStrong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Darkest White: A Mountain Legend and the Avalanche That Took HimFrom EverandThe Darkest White: A Mountain Legend and the Avalanche That Took HimRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Higher Love: Climbing and Skiing the Seven SummitsFrom EverandHigher Love: Climbing and Skiing the Seven SummitsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- Training for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersFrom EverandTraining for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (13)

- Training for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersFrom EverandTraining for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- The Art of Fear: Why Conquering Fear Won't Work and What to Do InsteadFrom EverandThe Art of Fear: Why Conquering Fear Won't Work and What to Do InsteadRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Unbound: A Story of Snow and Self-DiscoveryFrom EverandUnbound: A Story of Snow and Self-DiscoveryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Winterdance: The Fine Madness of Running the IditarodFrom EverandWinterdance: The Fine Madness of Running the IditarodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (279)

- Everything the Instructors Never Told You About Mogul SkiingFrom EverandEverything the Instructors Never Told You About Mogul SkiingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Climb to Conquer: The Untold Story of WWII's 10th Mountain Division Ski TroopsFrom EverandClimb to Conquer: The Untold Story of WWII's 10th Mountain Division Ski TroopsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Hockey: Hockey Made Easy: Beginner and Expert Strategies For Becoming A Better Hockey PlayerFrom EverandHockey: Hockey Made Easy: Beginner and Expert Strategies For Becoming A Better Hockey PlayerNo ratings yet

- Strong is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerFrom EverandStrong is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- The Art of Fear: Why Conquering Fear Won't Work and What to Do InsteadFrom EverandThe Art of Fear: Why Conquering Fear Won't Work and What to Do InsteadRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Frostbike: The Joy, Pain and Numbness of Winter CyclingFrom EverandFrostbike: The Joy, Pain and Numbness of Winter CyclingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Mistake-Free Golf: First Aid for Your Golfing BrainFrom EverandMistake-Free Golf: First Aid for Your Golfing BrainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Backcountry Avalanche Safety: A Guide to Managing Avalanche Risk - 4th EditionFrom EverandBackcountry Avalanche Safety: A Guide to Managing Avalanche Risk - 4th EditionNo ratings yet

- Written in the Snows: Across Time on Skis in the Pacific NorthwestFrom EverandWritten in the Snows: Across Time on Skis in the Pacific NorthwestNo ratings yet

- Have Board, Will Travel: The Definitive History of Surf, Skate, and SnowFrom EverandHave Board, Will Travel: The Definitive History of Surf, Skate, and SnowRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)