Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Popper and Philosophy of Education

Uploaded by

Swami GurunandCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Popper and Philosophy of Education

Uploaded by

Swami GurunandCopyright:

Available Formats

Karl

Popper_And_Philosophy_of_Education

It is possible to read most of Poppers work as an attempt to extend the

implications of the logic of falsification beyond the realm of science to

provide a general moral theory, the main features of which are as follows:

People should write and speak clearly because by doing so they

make their speech or writing more amenable to criticism and

falsification. The widespread appeal of Poppers work may be due in

part to the lucidity of his writing. He is consistent in making his own

work more amenable to criticism and falsification by speaking and

writing in this way. For example he explains that it is his custom

Whenever I am invited to speak in some place, to develop some

consequences of my views which I expect to be unacceptable to

the particular audience. For I believe that there is only one

excuse for a lecture: to challenge.

Rigour (firmness) is essential. Just as scientists should not

abandon their theories too lightly in the face of an apparently

anomalous observation. Those theories should be held good for

long enough to enable their rigorous testing. So too people

generally should not be too swayed by what might amount to

fashion.

Imagination should be encouraged. It takes an imaginative leap to

produce a theory that will challenge an already embedded theory or

set of theories. It is all too easy not to make the imaginative effort to

challenge that which has become orthodox.

The identification of real human problems provides the spur to

formulate a new theory, not the production of a set of aims. The

important question for Popper is which of the problems that face us is

most in need of solution not what final state ought to be brought

about.

Criticism is essential both to the growth of knowledge and to the

possibility of rationality. Rather than attempting to fend off criticism, a

Popperian encourages criticism in all fields of human endeavour.

Whereas friendship and acceptable human relations are often seen to

be based on an uncritical acceptance of certain norms of behaviour, for

Popper a culture of continuous criticism is to be preferred. Within this

culture, good interpersonal relations are characterised by the

willingness of people to accept that while they make tentative steps

to solve the problems they have, their solutions are always temporary

and guaranteed to be inadequate in the longer term.

Truth for Popper functions as a regulative ideal to guide problem-solving.

We may know that we have advanced when a theory is produced which

accounts for all the explanatory and predictive features of the old theory

and enables us to explain and predict new things. It is mistaken and

harmful to believe that we might ever have the final theory that contains

the truth however. There is something immensely attractive and liberating to

those who can accept it, in the fact that their work is bound to have

shortcomings and that others should be actively encouraged to identify

those shortcomings.

The man who welcomes and acts on criticism will prize it

almost above friendship: the man who fights it out of concern

to maintain his position is clinging to non-growth.

It might appear from the above that Poppers moral theory is exclusively

individualistic. That appearance is wrong because his antidogmatism and

fallibilism at the individual level is applied to the problems of social and

political organisation in his later works which include The Open Society and

Its Enemies (1945), and The Poverty of Historicism (1957).

The first of these is widely believed to offer one of the most trenchant

criticisms of Marxism ever written. It advocates a liberal, piecemeal

approach to social and political change. For Popper it is dangerous to give

social and institutional arrangements some permanence because those

arrangements will always turn out to be inadequate in the longer term. A

kind of institutional and social dynamism is to be preferred over

permanent hierarchies, the members of which may tend to spend more

time preserving their status than solving the problems that they were set

up to solve. In no sphere of human influence should it be imagined that the

final or utopian solution to a problem has been found.

The second attacks the idea that the future is somehow predictable by

studying the past the conspiracy theory of society as Popper (1963:

123) terms it. It should not be imagined that a study of the past will enable

the future to be predicted with any reliable degree of certainty. Nor should

it be believed that there is an overall design to the way things evolve.

Poppers theory of knowledge is coterminous with his theory of evolution.

Problem solving is the primal activity for humans and survival is the first

problem to be solved. The development of language may be regarded as

the result of sophisticated attempts to adjust to the environment. This has

enabled the third word of objective non-physical objects such as the

content of books, works of art, science and literature. Poppers three-world

ontology allows him to link the social with the individual and the cognitive with

the affective. Just as objective progress is made through unpredictable

interactions between the three worlds, so too individuals learn.

A Theory of Learning

Popper explains how an initial problem prompts the formation of a

trial solution which undergoes error elimination before giving rise to a new

problem and so on. This explanation has been developed into a Popperian

theory of learning as if Popper were a progressive who supposed that the

only form of useful learning must start with the persons own authentically

realised problem. (Swann 1998) A conservative interpretation of Poppers

work is possible too however. There is a place for inducting children into a

third world of ideas through what amounts to a kind of uncritical

transmission. The progressive interpretation of his work suggests that

children must be confident to face continual failure in the solution to

problems they actually care about solving. The conservative interpretation

stresses the transmission of objective knowledge including the

appreciation of a common logic between all forms of human enquiry. In all

forms there is an attempt to extend the understanding of experience by the

use of creative imagination subjected to critical control. It turns out that

science merely provides an easily understood example of how this takes

place because of its sharp confrontation with physical reality. In the case

of the arts for example, the confrontation is not so direct.

In all cases experience does not present itself in abstraction from

accumulated ways of making sense of experience. Children learn those

ways essentially through a process of dogmatic initiation into a third

world of objective knowledge which represents the accumulated wisdom

of mankind. This third world is not made up only of scientific knowledge

but of the arts, ethics, so-called practical pursuits and all forms of

practice and institutions that go to make up what might be called a

cultural inheritance. It is not possible and certainly not productive to try to

relearn all of what presently constitutes world three through a process of

individual problem solving. The better the initiation into this world the

more likely it is that the learner will go on to solve interesting problems

for herself. Those solutions might then become in time part of the

constantly evolving world three. The tradition of subjecting new theories

to critical discussion is for Popper an established part of that world that

ought to be communicated to the young along with the moral

requirements that were outlined earlier.

Learning proceeds through a process of bringing the prejudices of the past

to a new situation which presents learners with a problem situation as

those prejudices prove inadequate to understanding and acting in that

situation. It is not just an intellectual response that is called for here but

also an emotional onethe learner has to care about solving the problem

and be prepared to take an imaginative leap in trying to solve it.

Psychologically therefore a Popperian learner has to be not only

imaginative but also robust enough to persevere with a problem in the face

of what might be severe criticism, apparent rejection and failure. The idea

that learners can free themselves from this requirement or that they can

free themselves from the prejudices of the society into which they are

born could not be more wrong for Popper. Learning is not best

characterised as a psychological process in which something goes on in

individual heads as it were. Criticism and the formulation of new theories

are only possible in language which gives theories their objective character. For Popper, the second world of individual minds and their psychology

is irrelevant to both epistemology and the logic of learning. As he puts it in

his autobiography.

It is my opinion that most investigations into the psychology of creative

thought are pretty barren or else more logical than psychological. For

critical thought or error elimination, can be better characterised in logical

terms than in psychological terms... Most (or perhaps all) learning

consists in theory formation: that is, in the formation of expectations. The

formation of a theory or conjecture has always a dogmatic, and often a

critical phase.

... there can be no critical phase without a preceding dogmatic

phase, a phase in which somethingan expectation, a regularity

of behaviouris formed, so that error elimination can begin to

work on it.

Educational Organisation and Research

The logic of falsification may also be used to guide forms of organisation.

A form of organisation may be taken as a theory subject to the test of

experience. Policies, institutions, management structures, different forms

of human association and governance may be subjected to the same logic.

That seems to mean that Popper advocates a kind of permanent revolution

in which the possibility of change is unlimited. To be sure he argues in

favour of the democratic form of life because it is only through such a

form that people have the ability to dismiss governments on a regular

basis. He is less clear about the role of democracy within particular

institutions such as schools and factories however and recognises what might

be called the paradox of democracy. It is only possible to retain the

democratic form of life if certain values such as tolerance are widely held

constant. For example it may be necessary for governments to include

arrangements to isolate those who refuse to tolerate the views of others.

Equally it may be necessary to isolate governments from removal from

office to enable them to have the authority and stability to intervene

effectively.

It is easy to see that there is a parallel between Poppers advice to

scientists to hold on to certain theories in order to test a new theory and

his advice to politicians to establish governments that can hold on to power

long enough to enable intervention on behalf of what is held to be the

common good (Popper 1945: 125). There is a further parallel between

Poppers epistemology and political theory: just as Popper rejects

metaphysical essentialism so too he rejects utopianism. The what is a ...

type of question is as unhelpful as a what state ought to be type of

question. A more useful question is what state is likely to be least harmful

and most easily changed. His anti utopianism in politics matches his

fallibilism in epistemology and leads him to ask not how should we rule or

manage but how can we best avoid misrule, and mismanagement in order

to minimise harm.

His arguments serve as a useful corrective to the idea that policy should

be presented as if it were bound to lead to a particular state of affairs

without ever considering or building into policy the conditions under which

that state of affairs could be recognised. For Popper policy should include

its own means of evaluation by setting out a series of testable propositions

through which the success of policy can be judged. It should be framed in a

tentative way. The perceived need for policy evaluation arises out of a

mistaken empiricist epistemology within which policies are framed as if

they were a kind of worthy intention or design for an ideal state of affairs.

Within this epistemology research is conceived as the attempt to provide

the best means of achieving that state or evaluating the extent to which it

has been achieved. For a Popperian however, it is preferable to think of

policy, theory and practice as embodying different levels of theory conceived

as attempts to solve particular problems that seem in most urgent need of

solution. Research is the attempt to produce those different levels of

theory.

The type of educational research that involves the gathering of large

amounts of data in the hope that inductively some hypothesis will emerge

is therefore challenged by Poppers work. To detect a correlation between

two variables tells us nothing about either causation or whether those

variables will be correlated in the future. It is therefore wrong to assume

that through observation and data-gathering reliable or useful truths can

be produced. Conceptual research in education seems to be encouraged

by Popper however, providing it is based on problems which those

interested in education are trying to solve.

Genuine philosophical problems are always rooted in genuine problems outside

philosophy, and they die if their roots decay.... the purer a philosophical problem

becomes the more liable is its discussion to degenerate into empty verbalism.

Conclusion

It is clear that Poppers philosophy radically challenges much current

educational practice, particularly that which encourages the wilder forms of

progressivism and denigrates traditional teaching. His three world

ontology has curricular implications that have not been fully explored. It is

also clear that his philosophy has important implications for the ways that

educational institutions are organised and the ways that educational

research is carried out. It is perhaps not surprising at a time in which

philosophy of education has drawn upon analytic traditions in many parts

of the world and continental traditions in other parts, that Poppers work

has not featured prominently within it. There are also glaring difficulties with

his three-world ontology and version of pragmatism even though common

sense might seem to support both. Even the logic of falsification upon

which, I have argued, much of Poppers work rests is ambiguous with regard

to the need to decide whether to hold on to theories, produce ad-hoc

modifications of them or to reject them. Logic is insufficient to settle the

decision. A similar criticism may be levelled against his political philosophy

and against the under developed notion of a problem upon which it appears

to rest. Nevertheless his arguments against historicism and utopianism are

regularly cited. The recent resurgence of interest in constructivism

(Bereiter 1994) has also led to educational interest in his work. Moreover

the sheer humanity, lucidity and systematic scope of his work is attractive

to those who value open-mindedness, imagination and a constant

willingness to be corrected.

You might also like

- Falsification of The Atmospheric CO2 Greenhouse Effects Within The Frame of PhysicsDocument115 pagesFalsification of The Atmospheric CO2 Greenhouse Effects Within The Frame of PhysicsJack StrikerNo ratings yet

- Paul Dirac - Is There An AEtherDocument6 pagesPaul Dirac - Is There An AEtherBryan GraczykNo ratings yet

- The Nuclear Hoax: by Miles MathisDocument16 pagesThe Nuclear Hoax: by Miles MathisBlarg ErificNo ratings yet

- Dingle's Relativity CritiqueDocument7 pagesDingle's Relativity Critiquecygnus_11No ratings yet

- Robert S. MullikenDocument10 pagesRobert S. MullikenOmSilence2651No ratings yet

- The Stephen Crothers InterviewDocument9 pagesThe Stephen Crothers InterviewGlobal Unification International100% (1)

- Robert CoreyDocument8 pagesRobert CoreySteven CalNo ratings yet

- The Olduvai Theory Sliding Towards A Post Indus. Stone AgeDocument14 pagesThe Olduvai Theory Sliding Towards A Post Indus. Stone AgeDiego Estin GeymonatNo ratings yet

- Agar Transhumanism PDFDocument7 pagesAgar Transhumanism PDFAndres VaccariNo ratings yet

- Imperialism 1Document22 pagesImperialism 1api-302492929100% (1)

- Edwards - Human Genetic Diversity - Lewontin's FallacyDocument4 pagesEdwards - Human Genetic Diversity - Lewontin's FallacyNemester100% (1)

- Quasars and Pulsars by Dewey B LarsonDocument178 pagesQuasars and Pulsars by Dewey B Larsonjimbob1233No ratings yet

- Galileo's Mistake: A New Look at the Epic Confrontation between Galileo and the ChurchFrom EverandGalileo's Mistake: A New Look at the Epic Confrontation between Galileo and the ChurchRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (5)

- The Cosmic SerpentDocument3 pagesThe Cosmic SerpentJonathan Robert Kraus (OutofMudProductions)No ratings yet

- Biology of Cognition (Maturana)Document27 pagesBiology of Cognition (Maturana)telecultNo ratings yet

- Are Serial Killers Born or CreatedDocument7 pagesAre Serial Killers Born or CreatedDaniel Ryan WeberNo ratings yet

- Disturbing The UniverseDocument3 pagesDisturbing The UniverseSally MoremNo ratings yet

- The Frankfurt School of Social Research and The Pathologization of Gentile Group AllegiancesDocument56 pagesThe Frankfurt School of Social Research and The Pathologization of Gentile Group AllegiancesDer YuriNo ratings yet

- Comp6216 Wis IIDocument39 pagesComp6216 Wis IIprojectdoublexplus2No ratings yet

- Virilio and Ujica - Toward The End of Gravity IIDocument19 pagesVirilio and Ujica - Toward The End of Gravity IIeccles05534No ratings yet

- Steven Weinberg - The First Three Minutes - A Moderm View of The Origin of The Universe (1977)Document168 pagesSteven Weinberg - The First Three Minutes - A Moderm View of The Origin of The Universe (1977)5cr1bd33No ratings yet

- Dilemmas PDFDocument324 pagesDilemmas PDFRachmad YanuariantoNo ratings yet

- Genius of The TinkererDocument4 pagesGenius of The Tinkerershabir khanNo ratings yet

- Chertow IPAT Equation and Its Variants PDFDocument17 pagesChertow IPAT Equation and Its Variants PDFlahgritaNo ratings yet

- Smith, Pamela H. The Body of The Artisan: Art and Experience in The Scientific Revolution. Downloaded On Behalf of University of EdinburghDocument122 pagesSmith, Pamela H. The Body of The Artisan: Art and Experience in The Scientific Revolution. Downloaded On Behalf of University of Edinburghcarmenchanning100% (1)

- Michael Polanyi and Karl Mannheim: Debating Freedom and PlanningDocument24 pagesMichael Polanyi and Karl Mannheim: Debating Freedom and PlanningbengersonNo ratings yet

- The Survivor's Paradox: Psychological Consequences of The Khmer Rouge Rhetoric of ExterminationDocument12 pagesThe Survivor's Paradox: Psychological Consequences of The Khmer Rouge Rhetoric of ExterminationJosé TLNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Amusing Ourselves To Death Book Review 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Amusing Ourselves To Death Book Review 1Kennedy Gitonga ArithiNo ratings yet

- World Enough and Space-Time: The AbsolutistsDocument12 pagesWorld Enough and Space-Time: The AbsolutistsspourgitiNo ratings yet

- Bence Jones, Michael Faraday The Life and Letter Volume 2Document502 pagesBence Jones, Michael Faraday The Life and Letter Volume 2Suren VasilianNo ratings yet

- Postmodern EpistemologyDocument40 pagesPostmodern EpistemologyVinaya BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- The Rise of the Psychopath: Sexual Repression vs Self-RegulationDocument20 pagesThe Rise of the Psychopath: Sexual Repression vs Self-RegulationStiller Beobachter100% (1)

- Time Travel Coincidences ExplainedDocument9 pagesTime Travel Coincidences ExplainedThien Van TranNo ratings yet

- In the Light of the Electron Microscope in the Shadow of the Nobel PrizeFrom EverandIn the Light of the Electron Microscope in the Shadow of the Nobel PrizeNo ratings yet

- Chivers Seto Blanchard 2007Document14 pagesChivers Seto Blanchard 2007api-292904275No ratings yet

- Popper's Falsificationism MethodDocument2 pagesPopper's Falsificationism MethodKeith PisaniNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of NationsDocument157 pagesThe Psychology of NationsGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Evolution of The Topological Concept of ConnectedDocument8 pagesEvolution of The Topological Concept of ConnectedMarcelo Pirôpo0% (1)

- Medica Electrolytes FactSheetDocument2 pagesMedica Electrolytes FactSheetavianaiden100% (1)

- Margaret Mead - 'Changing Perspectives On Modernization' - Rethinking Modernization - Anthropological PerspectivesDocument9 pagesMargaret Mead - 'Changing Perspectives On Modernization' - Rethinking Modernization - Anthropological Perspectivesgeneva1027No ratings yet

- Anna Marmodoro Aristotle On Perceiving ObjectsDocument156 pagesAnna Marmodoro Aristotle On Perceiving Objects123KalimeroNo ratings yet

- Biotechnology And: Monstrosity MonstrosityDocument9 pagesBiotechnology And: Monstrosity MonstrosityPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Ernest Rutherford Biography PDFDocument2 pagesErnest Rutherford Biography PDFMike100% (1)

- (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science 19-1) Henry Mehlberg (Auth.), Robert S. Cohen (Eds.)-Time, Causality, And the Quantum Theory_ Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 1_ Essay on the CADocument324 pages(Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science 19-1) Henry Mehlberg (Auth.), Robert S. Cohen (Eds.)-Time, Causality, And the Quantum Theory_ Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 1_ Essay on the CAJorge Chavez ChilonNo ratings yet

- Copenhagen Interpretation - WikipediaDocument12 pagesCopenhagen Interpretation - WikipediaYn Foan100% (1)

- Setting Aside All Authority: Giovanni Battista Riccioli and the Science against Copernicus in the Age of GalileoFrom EverandSetting Aside All Authority: Giovanni Battista Riccioli and the Science against Copernicus in the Age of GalileoRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Isaiah Berlin - Political JudgmentDocument8 pagesIsaiah Berlin - Political JudgmentPhilip PecksonNo ratings yet

- Dissipative Structures and Weak TurbulenceFrom EverandDissipative Structures and Weak TurbulenceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Arani, Raffaella Bono, Ivan Giudice, Emilio Del Preparata, Gi - Qed Coherence and The Thermodyna PDFDocument29 pagesArani, Raffaella Bono, Ivan Giudice, Emilio Del Preparata, Gi - Qed Coherence and The Thermodyna PDFЮрий Юрий100% (1)

- The Man Who Proved Stephen Hawking WrongDocument6 pagesThe Man Who Proved Stephen Hawking WrongMizanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Science, Churchill and Me: The Autobiography of Hermann BondiFrom EverandScience, Churchill and Me: The Autobiography of Hermann BondiNo ratings yet

- Use of Situational Judgment Tests To Predict Job PerformanceDocument12 pagesUse of Situational Judgment Tests To Predict Job PerformanceSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Education for Peace: Addressing Prevalent Notions Against Minorities in the Indian ContextDocument17 pagesEducation for Peace: Addressing Prevalent Notions Against Minorities in the Indian ContextSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Empathy For Interpersonal Peace Effects PDFDocument7 pagesEmpathy For Interpersonal Peace Effects PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Practical Philosophy and Rational ReligionDocument1 pagePractical Philosophy and Rational ReligionSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Eastern ReligionsDocument20 pagesEastern ReligionsSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Neuroscience For The PDFDocument34 pagesAn Introduction To Neuroscience For The PDFSwami Gurunand100% (1)

- Teach Emotion Recognition to Children with AutismDocument9 pagesTeach Emotion Recognition to Children with AutismSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- India's Growth StoryDocument56 pagesIndia's Growth StorySwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Peace Education International Perspectiv PDFDocument96 pagesPeace Education International Perspectiv PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Human Brain A Review PDFDocument20 pagesGender Differences in Human Brain A Review PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Bridging Neuroscience and PeacebuildingDocument1 pageBridging Neuroscience and PeacebuildingSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Religion in The ClassroomDocument23 pagesReligion in The ClassroomSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- 4 Spirituality, Religion, & HealthDocument55 pages4 Spirituality, Religion, & HealthEliza DNNo ratings yet

- Eastern ReligionsDocument20 pagesEastern ReligionsSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Universal Humanism of Tagore: F. M. Anayet HossainDocument7 pagesUniversal Humanism of Tagore: F. M. Anayet HossainSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of The Multiverse PDFDocument19 pagesA Brief History of The Multiverse PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Peace and Religion Report.Document38 pagesPeace and Religion Report.Piet JassogneNo ratings yet

- Religion TodayDocument44 pagesReligion TodaySwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Science Religion and Human ExperienceDocument350 pagesScience Religion and Human ExperienceSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Anthropology of ReligionDocument60 pagesAnthropology of ReligionSwami Gurunand100% (1)

- Politics and ReligionDocument41 pagesPolitics and ReligionSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Religion & WarDocument25 pagesReligion & WarSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Religion and ScienceDocument8 pagesReligion and ScienceSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Ned HerrmannDocument32 pagesNed HerrmannSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

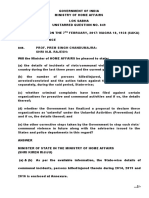

- Ministry of Home Affairs Communal Violence DataDocument4 pagesMinistry of Home Affairs Communal Violence DataSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Bks and Stories 2010Document16 pagesBks and Stories 2010Swami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Communal Riots PDFDocument158 pagesCommunal Riots PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- dBET ZenTexts 2005 PDFDocument341 pagesdBET ZenTexts 2005 PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Multiverse Sciam PDFDocument6 pagesMultiverse Sciam PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Assessment in Religious EducationDocument17 pagesAssessment in Religious EducationSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Phipps Charles MaryFrances 1952 ItalyDocument9 pagesPhipps Charles MaryFrances 1952 Italythe missions networkNo ratings yet

- The Sacred Substance AskokinDocument3 pagesThe Sacred Substance AskokinRemus Nicoara100% (1)

- Metanoia - Pocainta PDFDocument7 pagesMetanoia - Pocainta PDFdavidescu5costinNo ratings yet

- Testability and MeaningDocument47 pagesTestability and MeaningAdrián Fernández MartínNo ratings yet

- Kaleed Ul Tauheed Kalan (The Key of Divine Oneness (Detailed) )Document621 pagesKaleed Ul Tauheed Kalan (The Key of Divine Oneness (Detailed) )Sultan ul Faqr Publication100% (1)

- Spinoza and The Affective Turn: A Return To The Philosophical Origins of AffectDocument7 pagesSpinoza and The Affective Turn: A Return To The Philosophical Origins of AffectconololNo ratings yet

- St. Thomas's Fourth Way and Creation - Lawrence DewanDocument9 pagesSt. Thomas's Fourth Way and Creation - Lawrence DewanAngy MartellNo ratings yet

- John Caputo - The Return of Anti-Religion: From Radical Atheism To Radical TheologyDocument93 pagesJohn Caputo - The Return of Anti-Religion: From Radical Atheism To Radical TheologyBlake Huggins100% (1)

- Ego TunnelDocument6 pagesEgo TunnelSam0% (1)

- Alternative Spirituality in NZDocument292 pagesAlternative Spirituality in NZBarry Allen100% (1)

- Against Idols Wittgensteins DestructionDocument11 pagesAgainst Idols Wittgensteins DestructionAnonymous eAKJKKNo ratings yet

- Bergunder 2016 - Religion and Science Within A Global Religious HistoryDocument56 pagesBergunder 2016 - Religion and Science Within A Global Religious HistoryFabio MoralesNo ratings yet

- Derrida's Deconstruction of Husserl's Distinction Between Expressive and Indicative SignsDocument41 pagesDerrida's Deconstruction of Husserl's Distinction Between Expressive and Indicative SignsAjša Hadžić100% (1)

- Film TheoryDocument486 pagesFilm TheoryGandhi Wasuvitchayagit100% (3)

- Zenker and Fischer 2010 Bibliography of Conductive Arguments - V - 1 - 1Document5 pagesZenker and Fischer 2010 Bibliography of Conductive Arguments - V - 1 - 1Lucrecia BorgiaNo ratings yet

- A Companion To Meister Eckhart PDFDocument812 pagesA Companion To Meister Eckhart PDFKali Anee100% (10)

- Mind and BrainDocument17 pagesMind and Brainapi-235983903No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVES OF THE SELFDocument17 pagesChapter 1 PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVES OF THE SELFMLG FNo ratings yet

- QuotesDocument2 pagesQuotesJohn Paul AgtayNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT - ElsieDocument1 pageABSTRACT - ElsieCharrie Faye Magbitang HernandezNo ratings yet

- Metaphysics of Relation: Pabst's Study of Western ThoughtDocument473 pagesMetaphysics of Relation: Pabst's Study of Western ThoughtyurislvaNo ratings yet

- Review of Cyril O Regan Gnostic Return I PDFDocument4 pagesReview of Cyril O Regan Gnostic Return I PDFΜιλτος ΘεοδοσιουNo ratings yet

- Notes On Hegel's Shorter LogicDocument13 pagesNotes On Hegel's Shorter LogicShaun PoustNo ratings yet

- (Suny Series in Western Esoteric Traditions) Gyorgy E. Szonyi-John Dee's Occultism - Magical Exaltation Through Powerful Signs-State University of New York Press (2010)Document382 pages(Suny Series in Western Esoteric Traditions) Gyorgy E. Szonyi-John Dee's Occultism - Magical Exaltation Through Powerful Signs-State University of New York Press (2010)drwuss100% (17)

- JOHN LOCKE'S VIEW ON PERSONAL IDENTITYDocument7 pagesJOHN LOCKE'S VIEW ON PERSONAL IDENTITYJet LamisNo ratings yet

- EPISTEMOLOGYDocument8 pagesEPISTEMOLOGYSyed Hassan Abbas ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Ex 1.3 Propositional EquivalencesDocument21 pagesEx 1.3 Propositional EquivalencesMoiz MalikNo ratings yet

- MODULE 2. PhiloDocument3 pagesMODULE 2. PhiloMarieden RimandoNo ratings yet

- Henry E. Allison - Kant's Theory of Freedom (1990, Cambridge University Press)Document317 pagesHenry E. Allison - Kant's Theory of Freedom (1990, Cambridge University Press)montserratrrh100% (1)