Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mahasiddha: 1 Genealogy and Historical Dates

Uploaded by

ShivamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mahasiddha: 1 Genealogy and Historical Dates

Uploaded by

ShivamCopyright:

Available Formats

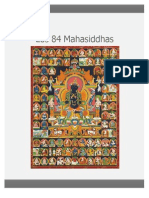

Mahasiddha

The Tantric communities of India in the

latter half of the rst Common Era millennium

(and perhaps even earlier) were something

like Institutes of Advanced Studies in relation to the great Buddhist monastic Universities. They were research centers for highly

cultivated, successfully graduated experts in

various branches of Inner Science (adhyatmavidya), some of whom were still monastics

and could move back and forth from university (vidyalaya) to site (patha), and many of

whom had resigned vows of poverty, celibacy,

and so forth, and were living in the classical

Indian sannysin or sdhu style. I call them

the psychonauts of the tradition, in parallel

with our astronauts, the materialist scientistadventurers whom we admire for their courageous explorations of the outer space which

we consider the matrix of material reality. Inverse astronauts, the psychonauts voyaged deep

into inner space, encountering and conquering angels and demons in the depths of their

subconscious minds.[1]

Mahasiddha Ghantapa, from Situ Panchen's set of thangka depicting the Eight Great Tantric Adepts. 18th century

1 Genealogy and historical dates

The exact genealogy and historical dates of the Mahasiddhas are contentious. Dowman (1986) holds that they all

Mahasiddha (Sanskrit: mahsiddha great adept;

lived between 750 and 1150 CE.

Tibetan: , Wylie: grub thob chen po, THL:

druptop chenpo ) is a term for someone who embodies and

cultivates the "siddhi of perfection. They are a certain

2 Primary tradition

type of yogin/yogini recognized in Vajrayana Buddhism.

Mahasiddhas were tantra practitioners or tantrikas who

had sucient empowerments and teachings to act as a Abhayadatta Sri is an Indian scholar of the 12th cenguru or tantric master. A siddha is an individual who, tury who is attributed with recording the hagiographies of

through the practice of sdhan, attains the realization of the eighty-four siddha in a text known as The History of

siddhis, psychic and spiritual abilities and powers. Their the Eighty-four Mahasiddha (Sanskrit: Caturasitisiddha

historical inuence throughout the Indian subcontinent pravrtti; Wylie: grub thob brgyad bcu tsa bzhi'i lo rgyus ).

and the Himalayas was vast and they reached mythic Dowman holds that the eighty-four Mahasiddha are spirproportions as codied in their songs of realization and itual archetypes:

hagiographies, or namtars, many of which have been preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. The Mahasiddhas

The number eighty-four is a whole or

are the founders of Vajrayana traditions and lineages such

perfect number. Thus the eighty-four sidas Dzogchen and Mahamudra.

dhas can be seen as archetypes representing

Robert Thurman explains the symbiotic relationship between Tantric Buddhist communities and the Buddhist

universities such as Nalanda which ourished at the same

time:

the thousands of exemplars and adepts of the

tantric way. The siddhas were remarkable for

the diversity of their family backgrounds and

the dissimilarity of their social roles. They

1

4

were found in every reach of the social structure: kings and ministers, priests and yogins,

poets and musicians, craftsmen and farmers,

housewives and whores.[2]

Reynolds (2007) states that the mahasiddha tradition

evolved in North India in the early Medieval Period

(313 cen. CE). Philosophically this movement was

based on the insights revealed in the Mahayana Sutras

and as systematized in the Madhyamaka and Chittamatrin schools of philosophy, but the methods of meditation

and practice were radically dierent than anything seen in

the monasteries.[3] He proers that the mahasiddha tradition broke with the conventions of Buddhist monastic

life of the time, and abandoning the monastery they practiced in the caves, the forests, and the country villages

of Northern India. In complete contrast to the settled

monastic establishment of their day, which concentrated

the Buddhist intelligenzia [sic.] in a limited number of

large monastic universities, they adopted the life-style of

itinerant mendicants, much as the wandering Sadhus of

modern India.[3]

GEOGRAPHICAL SITES

in both lists. In many instances more than one siddha with

the same name exists, so it must be assumed that fewer

than thirty siddhas of the two traditions actually relate to

the same historical persons. In the days when the siddhas

of the later Tibetan traditions ourished in India (i.e., between the 9th and 11th centuries), it was not uncommon

for initiates to assume the names of famous adepts of the

past. Sometimes a disciple would have the same name as

his guru, while still other names were based on caste or

tribe. In such a context the distinction between siddhas

of the same name becomes blurred. The entire process

of distinguishing between siddhas with the same name

of dierent texts and lineages is therefore to large extent

guesswork. The great variation in phonetic transcription

of Indian words into Tibetan may partly be the result of

various Tibetan dialects. In the process of copying the Tibetan transcriptions in later times, the spelling often became corrupted to such an extent that the recognition or

reconstitution of the original names became all but impossible. Whatever the reasons might be, the Tibetan

transcription of Indian names of mahasiddhas clearly becomes more and more corrupt as time passes.

The charnel ground conveys how great mahasiddhas in

the Nath and Vajrayana traditions such as Tilopa (988

1069) and Gorakshanath (. 11th 12th century) yoked

adversity to till the soil of the path and accomplish the 4 Geographical sites

fruit, the ground (Sanskrit: raya; Wylie: gzhi ) of

realization:[4]

Local folk tradition refers to a number of icons and sacred

sites to the eighty-four Mahasiddha at Bharmour (formerly known as Brahmapura) in the Chaurasi complex.[6]

The charnel ground is not merely the herThe word chaurasi means eighty-four.

mitage; it can also be discovered or revealed in

completely terrifying mundane environments

where practitioners nd themselves desperate

and depressed, where conventional worldly asIt is also very signicant that nowhere else,

pirations have become devastated by grim realexcept at Bharmaur in Chamba district, may

ity. This is demonstrated in the sacred biograbe seen the living tradition of the Eighty-four

phies of the great siddhas of the Vajrayna traSiddhas. In the Chaurasi temple complex, near

dition. Tilopa attained realization as a grinder

which the famous temple of goddess Lakshana

of sesame seeds and a procurer for a promi(8th century A.D.) stands, there once were

nent prostitute. Sarvabhaka was an extremely

eighty-four small shrines, each dedicated to a

obese glutton, Goraka was a cowherd in reSiddha.[7]

mote climes, Tatepa was addicted to gambling, and Kumbharipa was a destitute potter.

These circumstances were charnel grounds beA number of archaeological sacred sites require iconocause they were despised in Indian society and

graphic analysis in the Chaurasi complex in Chamba, Hithe siddhas were viewed as failures, marginal

machal Pradesh. Although it might be hagiographical acand deled.[5]

cretion and folk lore, it is said that in the reign of Sahil

Varman:

Other traditions

According to Ulrich von Schroeder, Tibet has dierent

traditions relating to the mahasiddhas. Among these traditions, two were particularly popular, namely the Abhayadatta Sri list and the so-called Vajrasana list. The

number of mahasiddhas varies between eighty-four and

eighty-eight, and only about thirty-six of the names occur

Soon after Sahil Varmans accession

Brahmapura was visited by 84 yogis/

mahasidhas, who were greatly pleased

with the Rajas piety and hospitality; and as he

ad no heir, they promised him ten sons and

in due course ten sons were born and also a

daughter named Champavati.

Catursiti-siddha-pravtti

the Kham, entered the Himalayan tantric tradition from

the Mahasiddha, Ngagpa and Bonpo. Dream Yoga or

The Caturasiti-siddha-pravrtti (CSP), The Lives of the "Milam" (T:rmi-lam; S:svapnadarana), is one of the Six

Eighty-four Siddhas, compiled by Abhayadatta Sri, a Yogas of Naropa.

Northern Indian Sanskrit text dating from the 11th or Four of the eighty-four Mahasiddhas are women.[9] They

12th century, comes from a tradition prevalent in the an- are:

cient city-state of Campa in the modern district of Bihar. Only Tibetan translations of this Sanskrit text seem

Manibhadra, the Perfect Wife

to have survived. This text was translated into Tibetan by

Lakshmincara, The Princess of Crazy wisdom

sMon grub Shes rab and is known as the Grub thob brgyad

cu rtsa bzhii lo rgyus or The Legends of the Eighty-four

Mekhala, the elder of the 2 Headless Sisters

Siddhas. It has been suggested that Abhayadatta Sri is

Kanakhala, the younger of the 2 Headless Sisters

identical with the great Indian scholar Mahapandita Abhayakaragupta (late 11thearly 12th century), the compiler of the iconographic compendiums Vajravali, Nis- Von Schroeder (2006) states:

pannayogavali, and Jyotirmanjari.

Some of the most important Tibetan BudThe other major Tibetan tradition is based on the list condhist

monuments to have survived the Cultural

tained in the Caturasiti-siddhabhyarthana (CSA) by RatRevolution

between 1966 and 1976 are located

nakaragupta of Vajrasana, identical with Bodhgaya (Tib.:

at

Gyantse

(rGyal rtse) in Tsang province of

rDo rje gdan) located in Bihar, Northern India. The TiCentral

Tibet.

For the study of Tibetan art, the

betan translation is known as Grub thob brgyad cu rtsa

temples

of

dPal

khor chos sde, namely the dPal

bzhii gsol debs by rDo rje gdan pa. There exist several

khor

gTsug

lag

khang and dPal khor mchod

Tibetan versions of the list of mahasiddhas based on the

rten,

are

for

various

reasons of great imporVajrasana text. However, these Tibetan texts dier in

tance.

The

detailed

information

gained from

many cases with regard to the Tibetan transcriptions of

[8]

the

inscriptions

with

regard

to

the

sculptors

the Indian mahasiddhas names.

and painters summoned for the work testies to

the regional distribution of workshops in 15thcentury Tsang. The sculptures and murals also

6 Eighty-four Mahasiddhas

document the extent to which a general consensus among the various traditions or schools

had been achieved by the middle of that cenBy convention there are eighty-four Mahasiddhas in both

tury. Of particular interest is the painted cycle

Hindu and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, with some overof eighty-four mahsiddhas, each with a name

lap between the two lists. The number is congruent with

inscribed in Tibetan script. These paintings

the number of siddhi or occult powers held in the Indian

of mahasiddhas, or great perfected ones enReligions. In Tibetan Buddhist art they are often depicted

dowed with supernatural faculties (Tib. Grub

together as a matched set in works such as thangka paintchen), are located in the Lamdre chapel (Lam

ings where they may be used collectively as border decobras lha khang) on the second oor of the

rations around a central gure.

dPal khor gTsug lag khang. Bearing in mind

Each Mahasiddha has come to be known for certain charthat these murals are the most splendid extant

acteristics and teachings, which facilitates their pedagogpainted Tibetan representations of mahasidical use. One of the most beloved Mahasiddhas is Virupa,

dhas, one wonders why they have never been

who may be taken as the patron saint of the Sakyapa sect

published as a whole cycle. Several scholars

and instituted the Lamdr (Tibetan: lam 'bras) teachings.

have at times intended to study these paintVirupa (alternate orthographies: Birwapa/Birupa) lived

ings, but it seems that diculties of identiin 9th century India and was known for his great attaincation were the primary obstacle to publicaments.

tion. Although the life-stories of many of the

Some of the methods and practices of the Mahasiddha

eighty-four mahasiddhas still remain unidentiwere codied in Buddhist scriptures known as Tantras.

ed, the quality of the works nevertheless warTraditionally the ultimate source of these methods and

rants a publication of these great murals. There

practices is held to be the historical Buddha Shakyamuni,

seems to be some confusion about the numbut often it is a transhistorical aspect of the Buddha or deber of mahsiddhas painted on the walls of the

ity Vajradhara or Samantabhadra who reveals the Tantra

Lam bras lha khang. This is due to the fact

in question directly to the Mahasiddha in a vision or whilst

that the inscription below the paintings menthey dream or are in a trance. This form of the deity is

tions eighty siddhas, whereas actually eightyknown as a sambhogakaya manifestation. The sadhana of

four were originally represented. [Note: AcDream Yoga as practiced in Dzogchen traditions such as

cording to the Myang chos byung, eighty-eight

6

siddhas are represented. G. Tucci mentions

eighty-four, whereas Erberto Lo Bue assumed

that only eighty siddhas were shown, as stated

in the inscription. Cf. Lo Bue, E. F. andRicca, F. 1990. Gyantse Revisited, pp. 411

32, pls. 14760]. Of these eighty-four siddhas

painted on the walls, two are entirely destroyed

(G55, G63) and another retains only the lower

section; the name has survived (G56). Thus,

the inscribed Tibetan names of eighty-two mahasiddhas are known. Of the original eightysix paintings, eighty-four represent a cycle of

mahsiddhas (G1G84).[8]

6.1

List of the Mahasiddhas

EIGHTY-FOUR MAHASIDDHAS

24. Dukhandi, the Scavenger";

25. Ghantapa, the Celibate Bell-Ringer";

26. Gharbari or Gharbaripa, the Contrite Scholar

(Skt., pandita);

27. Godhuripa, the Bird Catcher";

28. Goraksha, the Immortal Cowherd";

29. Indrabhuti, the Enlightened Siddha-King";

30. Jalandhara, the Dakinis Chosen One";

31. Jayananda, the Crow Master";

32. Jogipa, the Siddha-Pilgrim";

33. Kalapa, the Handsome Madman";

In Buddhism there are eighty-four Mahasiddhas (an asterisk denotes a female Mahasiddha):

34. Kamparipa, the Blacksmith";

1. Acinta, the Avaricious Hermit";

35. Kambala (Lavapa), the Black-Blanket-Clad Yogin);

2. Ajogi, the Rejected Wastrel";

36. Kanakhala*, the younger Severed-Headed Sister;

3. Anangapa, the Handsome Fool";

37. Kanhapa (Krishnacharya), the Dark Siddha";

4. Aryadeva (Karnaripa), the One-Eyed";

38. Kankana, the Siddha-King";

5. Babhaha, the Free Lover";

39. Kankaripa, the Lovelorn Widower";

6. Bhadrapa, the Exclusive Brahmin";

40. Kantalipa, the Ragman-Tailor";

7. Bhandepa, the Envious God";

41. Kapalapa, the Skull Bearer";

8. Bhiksanapa, Siddha Two-Teeth";

42. Khadgapa, the Fearless Thief";

9. Bhusuku (Shantideva), the Idle Monk";

43. Kilakilapa, the Exiled Loud-Mouth";

10. Camaripa, the Divine Cobbler";

44. Kirapalapa (Kilapa), the Repentant Conqueror";

11. Champaka, the Flower King";

45. Kokilipa, the Complacent Aesthete";

12. Carbaripa (Carpati) the Petrifyer";

13. Catrapa, the Lucky Beggar";

46. Kotalipa (or Tog tse pa, the Peasant Guru";

47. Kucipa, the Goitre-Necked Yogin";

14. Caurangipa, the Dismembered Stepson";

48. Kukkuripa, (late 9th/10th Century), the Dog

Lover";

15. Celukapa, the Revitalized Drone";

49. Kumbharipa, the Potter";

16. Darikapa, the Slave-King of the Temple Whore";

50. Laksminkara*, The Mad Princess";

17. Dengipa, the Courtesans Brahmin Slave";

51. Lilapa, the Royal Hedonist";

18. Dhahulipa, the Blistered Rope-Maker";

52. Lucikapa, the Escapist";

19. Dharmapa, the Eternal Student (c.900 CE);

53. Luipa, the Fish-Gut Eater";

20. Dhilipa, the Epicurean Merchant";

54. Mahipa, the Greatest";

21. Dhobipa, the Wise Washerman";

55. Manibhadra*, the Happy Housewife";

22. Dhokaripa, the Bowl-Bearer";

56. Medhini, the Tired Farmer";

23. Dombipa Heruka, the Tiger Rider";

57. Mekhala*, the Elder Severed-Headed Sister;

6.2

Names according to the Abhayadatta Sri tradition

58. Mekopa, the Guru Dread-Stare";

6.2 Names according to the Abhayadatta

Sri tradition

59. Minapa, the Fisherman";

60. Nagabodhi, the Red-Horned Thief'";

61. Nagarjuna, Philosopher and Alchemist";

62. Nalinapa, the Self-Reliant Prince";

63. Nirgunapa, the Enlightened Moron";

64. Naropa, the Dauntless";

65. Pacaripa, the Pastrycook";

66. Pankajapa, the Lotus-Born Brahmin";

According to Ulrich von Schroeder, Tibet has dierent

traditions relating to the mahasiddhas. Among these traditions, two were particularly popular, namely the Abhayadatta Sri list and the so-called Vajrasana list. The

number of mahasiddhas varies between eighty-four and

eighty-eight, and only about thirty-six of the names occur in both lists. It is therefore also wrong to state

that in Buddhism are 84 Mahasiddhas. The correct title should therefore be Names of the 84 Mahasiddhas according to the Abhayadatta Sri Tradition. It should also be

clearly stated that only Tibetan translations of this Sanskrit text Caturasiti-siddha-pravrtti (CSP) or The Lives

of the Eighty-four Siddhas seem to have survived. This

means that many Sanskrit names of the Abhayadatta Sri

tradition had to be reconstructed and perhaps not always

correctly.

67. Putalipa, the Mendicant Icon-Bearer";

68. Rahula, the Rejuvenated Dotard";

6.3 Identication

According to Ulrich von Schroeder for the identication

of Mahasiddhas inscribed with Tibetan names it is necessary to reconstruct the Indian names. This is a very

Sakara or Saroruha;

dicult task because the Tibetans are very inconsistent

with the transcription or translation of Indian personal

Samudra, the Pearl Diver";

names and therefore many dierent spellings do exist.

When comparing the dierent Tibetan texts on mahasidntipa (or Ratnkaranti), the Complacent Misdhas, we can see that the transcription or translation of

sionary";

the names of the Indian masters into the Tibetan language

was inconsistent and confused. The most unsettling exSarvabhaksa, the Glutton);

ample is an illustrated Tibetan block print from Mongolia about the mahasiddhas, where the spellings in the text

Savaripa, the Hunter, held to have incarnated in vary greatly from the captions of the xylographs.[10] To

Drukpa Knleg;

quote a few examples: Kankaripa [Skt.] is named Kam

ka li/Kangga la pa; Goraksa [Skt.]: Go ra kha/Gau raksi;

Syalipa, the Jackal Yogin";

Tilopa [Skt.]: Ti la blo ba/Ti lla pa; Dukhandi [Skt.]:

Dha khan dhi pa/Dwa kanti; Dhobipa [Skt.]: Tom bhi

pa/Dhu pi ra; Dengipa (CSP 31): Deng gi pa / Tinggi

Tantepa, the Gambler";

pa; Dhokaripa [Skt.]: Dho ka ra / Dhe ki ri pa; Carbaripa (Carpati) [Skt.]: Tsa ba ri pa/Tsa rwa ti pa; Sakara

Tantipa, the Senile Weaver";

[Skt.]: Phu rtsas ga/Ka ra pa; Putalipa [Skt.]: Pu ta la/

Bu ta li, etc. In the same illustrated Tibetan text we nd

Thaganapa, the Compulsive Liar";

another inconsistency: the alternate use of transcription

and translation. Examples are Nagarjuna [Skt.]: Na gai

Tilopa, the Great Renunciate

dzu na/Klu sgrub; Aryadeva (Karnaripa) [Skt.]: Ka na ri

pa/Phags pa lha; and Ghantapa [Skt.]: Ghanda pa/rDo

Udhilipa, the Bird-Man";

rje dril bu pa, to name a few.[8]

69. Saraha, the Great Brahmin";

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81. Upanaha, the Bootmaker";

82. Vinapa, the Musician";

83. Virupa, the Dakini Master";

84. Vyalipa, the Courtesans Alchemist.

6.4 Concordance lists

For the identication of individual mahasiddhas the concordance lists published by Ulrich von Schroeder are useful tools for every scholar. The purpose of the concordance lists published in the appendices of his book is pri-

11 FURTHER READING

marily for the reconstitution of the Indian names, regardless of whether they actually represent the same historical

person or not. The index of his book contains more than

1000 dierent Tibetan spellings of mahasiddha names.[8]

Other mahasiddhas

Tibetan masters of various lineages are often referred

to as mahasiddhas. Among them are Marpa, the Tibetan translator who brought Buddhist texts to Tibet, and

Milarepa. In Buddhist iconography, Milarepa is often

represented with his right hand cupped against his ear, to

listen to the needs of all beings. Another interpretation of

the imagery is that the teacher is engaged in a secret yogic

exercise (e.g. see Lukhang). (Note: Marpa and Milarepa

are not mahasiddhas in the historical sense, meaning they

are not 2 of the 84 traditional mahasiddhas. However,

this says nothing about their realization.) Lawapa the progenitor of Dream Yoga sadhana was a mahasiddha.

See also

Charyapada

Gorakshanath

Matsyendranath

Twilight language

Notes

[1] David B. Gray, ed. (2007). The Cakrasamvara

Tantra: The Discourse of r Heruka (rherukbhidhna). Thomas F. Yarnall. American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. pp. ixx. ISBN

978-0-9753734-6-0.

[2] Dowman, Keith (1984). The Eighty-four Mahasiddhas

and the Path of Tantra. KeithDowman.net. Retrieved

2015-03-21. From the Introduction to Masters of Mahamudra, SUNY, 1984.

[3] Reynolds, John Myrdhin. The Mahasiddha Tradition in

Tibet. Vajranatha. Vajranatha. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

[4] Dudjom Rinpoche (2002), p. 535

[5] Simmer-Brown (2002), p. 127

[6] H (1994), p. 85

[7] H (1994), p. 98

[8] von Schroeder (2006)

[9] Names of the 84 Mahasiddhas. Yoniversum.nl. Retrieved 2015-03-21.

[10] Egyed (1984)

10 References

Dowman, Keith (1986). Masters of Mahamudra:

Songs and Histories of the Eighty-four Buddhist Siddhas. SUNY Series in Buddhist Studies. Albany,

NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 088706-160-5.

Dudjom Rinpoche (Jikdrel Yeshe Dorje) (2002).

The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. Translated and edited by

Gyurme Dorje with Matthew Kapstein (2nd ed.).

Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-0878.

Egyed, Alice (1984). The Eighty-four Siddhas: A

Tibetan Blockprint from Mongolia. Akadmiai Kiad. ISBN 9630538350.

Gray, David B. (2007). The Cakrasamvara Tantra

(The Discourse of Sri Heruka): A Study and Annotated Translation. Treasury of the Buddhist

Sciences. Columbia University Press. ISBN

0975373463.

H, Omacanda (1994). Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D.

Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788185182995.

Simmer-Brown, Judith (2002). Dakinis Warm

Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1-57062-920-4.

von Schroeder, Ulrich (2006). Empowered Masters: Tibetan Wall Paintings of Mahasiddhas at

Gyantse. Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN

978-1932476248.

11 Further reading

Downs, H. R. (1999). The Mahasiddha Linedrawings of H. R. Downs. KeithDowman.net. Retrieved

2015-03-21. Also in Dowman (1986).

Moudud, Hasna Jasimuddin (1992). The Caraypadas the Yoga Songs and Poetry of the Maha

Siddhas. A Thousand Year Old Bengali Mystic Poetry. Bangladesh: University Press. ISBN

9840511939.

Reynolds, John Myrdhin. The Mahasiddha Tradition In Tibet. Vajranatha.com. Retrieved 201503-21.

White, David Gordon (1998). The Alchemical Body:

Siddha Traditions in Medieval India (1st ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226894997.

Yuthok, Lama Choedak (1997). Lamdre: Dawn

of Enlightenment (PDF). Canberra, Australia:

Goram Publications. ISBN 0-9587085-0-9.

12

External links

The 84 Indian Adepts of Abhayadatta System

Mahasiddha: Buddhist Tantric Teachers of India

13

13

13.1

TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

Text

Mahasiddha Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahasiddha?oldid=671452723 Contributors: Andres, Technopilgrim, Carlossuarez46,

Home Row Keysplurge, Andycjp, Haiduc, Mairi, Giraedata, Ogress, Hanuman Das, Woohookitty, BD2412, Amire80, TheRingess,

FlaBot, Pigman, David Woodward, Gaius Cornelius, Sylvain1972, Seemagoel, Kungfuadam, SmackBot, MrDemeanour, BoBo, Mhss,

Bluebot, Klimov, Snowgrouse, Highpriority, DabMachine, Bisco, Ekajati, Cydebot, Eu.stefan, Thijs!bot, Klasovsky, RobotG, Bluestone55,

Alphachimpbot, Bakasuprman, B9 hummingbird hovering, R'n'B, Pharaoh of the Wizards, Johnbod, Morinae, A Ramachandran, IPSOS, Davin, Benevolent56, Cundi, SieBot, AdamHolt, Dakinijones, Msempty, Editor2020, Mitsube, Thecontemplative, Addbot, Lykos,

Sivanath, Tengu800, Lightbot, Mahasiddhadharma, Yobot, Truthirst, AnomieBOT, LilHelpa, Xqbot, Termininja, HRoestBot, Skyerise,

Theprofessordoctor, DiHri, Oshodhara, Leopold Jena, Alfredo ougaowen, ZroBot, ClueBot NG, Dream of Nyx, Helpful Pixie Bot, PhnomPencil, Marcocapelle, Joshua Jonathan, CO2Northeast, Hmainsbot1, TenzinNamdak, PizzaOven, Merigar, Totalenlightenment, The

ancient princess, Hiqi and Anonymous: 39

13.2

Images

File:Situ_Panchen._Mahasiddha_Ghantapa._From_Situ{}s_set_of_the_Eight_Great_Tantric_Adepts._18th_century,_Coll.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dc/Situ_Panchen._Mahasiddha_

_of_John_and_Berthe_Ford..jpg Source:

Ghantapa._From_Situ%27s_set_of_the_Eight_Great_Tantric_Adepts._18th_century%2C_Coll._of_John_and_Berthe_Ford..jpg

License: Public domain Contributors: http://www.academia.edu/1849580/_Lama_Patron_and_Artist_The_Great_Situ_Panchen_in_Arts_

of_Asia_March_2010_pp._82-92 Original artist: Situ Panchen

13.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

You might also like

- Shakti - Goddess in HinduismDocument5 pagesShakti - Goddess in HinduismShivamNo ratings yet

- 5 Families of DakinisDocument12 pages5 Families of DakinisCLG100% (3)

- Shakti Rupa - A Comparative Study of Female Deities in Hinduism, Buddhism and Bon TantraDocument72 pagesShakti Rupa - A Comparative Study of Female Deities in Hinduism, Buddhism and Bon Tantratahuti696100% (7)

- Kundalini - The Personal Transformational EnergyDocument8 pagesKundalini - The Personal Transformational EnergyShivam100% (2)

- Chakrasamvara Luipa ABShort Low ResDocument14 pagesChakrasamvara Luipa ABShort Low ResLim Kew Chong100% (8)

- Vajrasattva Sadhana+ PDFDocument8 pagesVajrasattva Sadhana+ PDFGede GiriNo ratings yet

- The Dakini PrincipalDocument22 pagesThe Dakini PrincipalGonpo Jack100% (2)

- KaliDocument14 pagesKaliShivamNo ratings yet

- Alvars - Vaishnava Poet SaintsDocument4 pagesAlvars - Vaishnava Poet SaintsShivamNo ratings yet

- Sadhana of The White DakiniDocument13 pagesSadhana of The White DakiniJohn KellyNo ratings yet

- Bon Po Hidden Treasures - A Catalogue of Gter Ston Bde Chen Gling Pa's Collected Revelations (Brill's Tibetan Studies Library, V. 6) (PDFDrive)Document323 pagesBon Po Hidden Treasures - A Catalogue of Gter Ston Bde Chen Gling Pa's Collected Revelations (Brill's Tibetan Studies Library, V. 6) (PDFDrive)vargus12No ratings yet

- How To Offer 1000 Tsog Offerings c5Document8 pagesHow To Offer 1000 Tsog Offerings c5Andre HscNo ratings yet

- Gandharva TantraDocument23 pagesGandharva TantraShanthi GowthamNo ratings yet

- The Tara Tantra: Tara's Fundamental Ritual Text (Tara-mula-kalpa)From EverandThe Tara Tantra: Tara's Fundamental Ritual Text (Tara-mula-kalpa)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Mahamaya Tantra - 84000Document40 pagesThe Mahamaya Tantra - 84000TomNo ratings yet

- Karmapa ControversyDocument10 pagesKarmapa ControversyCine MvsevmNo ratings yet

- KTR Graz Tenfold Powerfuld Kalachakra MantraDocument2 pagesKTR Graz Tenfold Powerfuld Kalachakra Mantraalbertmelondi100% (1)

- Bon Ka Ba Nag Po and The Rnying Ma Phur PaDocument17 pagesBon Ka Ba Nag Po and The Rnying Ma Phur Paar9vegaNo ratings yet

- Jigphun Guru YogaDocument5 pagesJigphun Guru YogaShenphen OzerNo ratings yet

- Water Bowl Offering Dudjom TersarDocument1 pageWater Bowl Offering Dudjom TersarLim Kew ChongNo ratings yet

- The Extraordinary Teaching of Glorious Sovereign WisdomDocument2 pagesThe Extraordinary Teaching of Glorious Sovereign WisdomJigme OzerNo ratings yet

- YoginiDocument8 pagesYoginiRishikhant100% (1)

- The Nath Sampradaya - IntroductionDocument6 pagesThe Nath Sampradaya - IntroductionShivamNo ratings yet

- The Hook of Red LighteningDocument8 pagesThe Hook of Red LighteningHoai Thanh Vu100% (1)

- BUDDHISM - Milarepa's Essential Song'sDocument47 pagesBUDDHISM - Milarepa's Essential Song'smaxalexandrNo ratings yet

- Kaulajnananirnaya TantraDocument2 pagesKaulajnananirnaya TantraSean GriffinNo ratings yet

- Hanuman - Introduction To One of The Chief Characters of RamayanaDocument19 pagesHanuman - Introduction To One of The Chief Characters of RamayanaShivam100% (3)

- ŚRĪ-HEVAJRA-MAHĀTANTRARĀJĀ (Folk - Uio.no-Braarvig-Hevajra-Hevajra SanskritDocument8 pagesŚRĪ-HEVAJRA-MAHĀTANTRARĀJĀ (Folk - Uio.no-Braarvig-Hevajra-Hevajra SanskrittgerloffNo ratings yet

- Mahamaya TantraDocument28 pagesMahamaya TantraAndrés Gosis100% (1)

- Tara (Devi)Document3 pagesTara (Devi)ShivamNo ratings yet

- Vajra YoginiDocument3 pagesVajra Yogininieotyagi100% (1)

- VishishtadvaitaDocument8 pagesVishishtadvaitaShivamNo ratings yet

- Vajravarahi PrayerDocument1 pageVajravarahi Prayerpaolo the best(ia)No ratings yet

- Mahakala Puja 2Document11 pagesMahakala Puja 2Ricky MonsalveNo ratings yet

- Religions of IndiaDocument24 pagesReligions of IndiaShivamNo ratings yet

- Vajrayogini: Her Visualization, Rituals, and FormsFrom EverandVajrayogini: Her Visualization, Rituals, and FormsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Advaita VedantaDocument30 pagesAdvaita VedantaShivam100% (3)

- Essence of The Two Accumulations Zab Tig Sgrol Ma Ti enDocument50 pagesEssence of The Two Accumulations Zab Tig Sgrol Ma Ti entendzinamNo ratings yet

- Mahamudra Lineage PrayerDocument2 pagesMahamudra Lineage PrayercepheisNo ratings yet

- Taking Eight PreceptsDocument11 pagesTaking Eight PreceptsShenphen OzerNo ratings yet

- Kiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian ContextsFrom EverandKiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian ContextsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Mahakala PrayerDocument3 pagesMahakala PrayerNilsonMarianoFilhoNo ratings yet

- Amritasiddhi PDFDocument19 pagesAmritasiddhi PDFAbhishekChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- VY Hand OffDocument12 pagesVY Hand OffMartin Jean0% (1)

- Kalachakra Empowerment Explained Khentrul Jamphal Lodro Rinpoche 061211Document5 pagesKalachakra Empowerment Explained Khentrul Jamphal Lodro Rinpoche 061211jjustinnNo ratings yet

- Essays On Shambhala Buddhist ChantsDocument110 pagesEssays On Shambhala Buddhist Chantssandip100% (5)

- Thrangu Rinpoche - The Spiritual Song of Lodro Thaye-Zhyisil Chokyi Chatsal (2008) PDFDocument176 pagesThrangu Rinpoche - The Spiritual Song of Lodro Thaye-Zhyisil Chokyi Chatsal (2008) PDFAndriy Voronov100% (2)

- Shiksha - VedangaDocument5 pagesShiksha - VedangaShivam100% (1)

- Parabhairavayogābhyāsāḥ: Practices in Parabhairavayoga - Volume 1From EverandParabhairavayogābhyāsāḥ: Practices in Parabhairavayoga - Volume 1No ratings yet

- Longchenpa's LifeDocument14 pagesLongchenpa's Lifeའཇིགས་བྲལ་ བསམ་གཏན་No ratings yet

- The Sutra On Wisdom at The Hour of Death - 84000Document18 pagesThe Sutra On Wisdom at The Hour of Death - 84000TomNo ratings yet

- He Vajra PDFDocument13 pagesHe Vajra PDFIoana IoanaNo ratings yet

- Tripura SundariDocument7 pagesTripura SundariShivamNo ratings yet

- Ganden Lha GyeDocument34 pagesGanden Lha GyekarmasamdrupNo ratings yet

- Praise To Shakyamuni BuddhaDocument18 pagesPraise To Shakyamuni BuddhaShiong-Ming LowNo ratings yet

- The Left Hand of Tantra, Part 1Document5 pagesThe Left Hand of Tantra, Part 1Giano BellonaNo ratings yet

- The Ritual of The Bodhisattva VowDocument172 pagesThe Ritual of The Bodhisattva VowNed BranchiNo ratings yet

- Bonpo Guru Yoga of TapihritsaDocument11 pagesBonpo Guru Yoga of TapihritsaCarlos Otero Robledo67% (3)

- SANDERSON - How Buddhist Is The HerukabhidhanaViennaDocument10 pagesSANDERSON - How Buddhist Is The HerukabhidhanaViennaMarco PassavantiNo ratings yet

- Shiva Darshana: Pancha-Brahma MantrasDocument3 pagesShiva Darshana: Pancha-Brahma Mantrasamnotaname4522100% (1)

- Kilaya Sadhana 5Document7 pagesKilaya Sadhana 5Devino AngNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Zabmo Yangthig Empowerment Commentary - Yangthang RinpocheDocument12 pagesExcerpt From Zabmo Yangthig Empowerment Commentary - Yangthang RinpocheMac DorjeNo ratings yet

- Lake of Lotus (5) - The Life Story of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche (1904-1987) - by Vajra Master Yeshe Thaye-Dudjom Buddhist AssociationDocument5 pagesLake of Lotus (5) - The Life Story of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche (1904-1987) - by Vajra Master Yeshe Thaye-Dudjom Buddhist AssociationDudjomBuddhistAsso100% (1)

- Nayanars - Tamil Shaiva SaintsDocument3 pagesNayanars - Tamil Shaiva SaintsShivamNo ratings yet

- White Tara PracticeDocument19 pagesWhite Tara Practicebutterlampz100% (4)

- Amrita SiddhiDocument19 pagesAmrita Siddhicontemplative100% (1)

- AvalokitesvaraDocument10 pagesAvalokitesvaraJesus MarreroNo ratings yet

- Vajra Songs of The Indian SiddhasDocument21 pagesVajra Songs of The Indian SiddhasHeruka108100% (1)

- Adi ParashaktiDocument7 pagesAdi ParashaktiShivam100% (1)

- DATESDocument42 pagesDATESEricNo ratings yet

- Guru Rinpoche's: Prayers ForDocument20 pagesGuru Rinpoche's: Prayers Forrobin drukNo ratings yet

- Ebook - 84 Mahassidas PDFDocument119 pagesEbook - 84 Mahassidas PDFJohnW1689100% (3)

- Siddhas - A Basic IntroductionDocument6 pagesSiddhas - A Basic IntroductionShivamNo ratings yet

- The King of Prayers: A Commentary on The Noble King of Prayers of Excellent ConductFrom EverandThe King of Prayers: A Commentary on The Noble King of Prayers of Excellent ConductNo ratings yet

- 84 MahasiddhasDocument98 pages84 Mahasiddhasricksuda100% (1)

- Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen Tsa Lung Sol DepDocument7 pagesShardza Tashi Gyaltsen Tsa Lung Sol Depleonardo.murcia100% (1)

- Urmikaularnava VELTHIUSDocument53 pagesUrmikaularnava VELTHIUSrohitindiaNo ratings yet

- Names of The 84 Mahasiddhas FromDocument6 pagesNames of The 84 Mahasiddhas FromSrinathvrNo ratings yet

- Ujjain TantraDocument3 pagesUjjain Tantrasriramnayak100% (1)

- DharmapalaDocument2 pagesDharmapalaAlexandre CruzNo ratings yet

- Mandala OfferingDocument3 pagesMandala OfferingunsuiboddhiNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Habitual PatternsDocument1 pageThe Nature of Habitual PatternsShyonnuNo ratings yet

- Concise Summary of Mahamudra - MaitripaDocument2 pagesConcise Summary of Mahamudra - Maitripaar9vegaNo ratings yet

- Seven Treasures蓮師七寶藏Document3 pagesSeven Treasures蓮師七寶藏Lim Kew ChongNo ratings yet

- 118 Durga Saptsati WebDocument240 pages118 Durga Saptsati Webmca_javaNo ratings yet

- Siddha Medicine - AboutDocument5 pagesSiddha Medicine - AboutShivam100% (1)

- Krishna JanmashtamiDocument5 pagesKrishna JanmashtamiShivamNo ratings yet

- Rama NavamiDocument4 pagesRama NavamiShivamNo ratings yet

- Shripad Shri VallabhaDocument5 pagesShripad Shri VallabhaShivam100% (1)

- Ekadashi - Description of Ekadasi FastDocument3 pagesEkadashi - Description of Ekadasi FastShivamNo ratings yet

- Vedic Brahmanism in IndiaDocument9 pagesVedic Brahmanism in IndiaShivamNo ratings yet

- Achintya Bheda AbhedaDocument4 pagesAchintya Bheda AbhedaShivamNo ratings yet

- Prahlada - The Asura PrinceDocument4 pagesPrahlada - The Asura PrinceShivamNo ratings yet

- Dvaita VedantaDocument4 pagesDvaita VedantaShivamNo ratings yet

- Samkhya - Hindu Philosophical SchoolDocument12 pagesSamkhya - Hindu Philosophical SchoolShivamNo ratings yet

- Narada - The Singing Vaishnava SaintDocument4 pagesNarada - The Singing Vaishnava SaintShivamNo ratings yet

- Shiva - The Auspicious OneDocument23 pagesShiva - The Auspicious OneShivamNo ratings yet

- Arjuna - The Warrior Devotee of KrishnaDocument14 pagesArjuna - The Warrior Devotee of KrishnaShivamNo ratings yet

- The Drinking Song Kyabjé Düd'Jom Rinpoche: HungDocument1 pageThe Drinking Song Kyabjé Düd'Jom Rinpoche: HungLama GyurmeNo ratings yet

- Tibet 7 Index PDFDocument4 pagesTibet 7 Index PDFAna VinkerlicNo ratings yet

- The Bright Mind Between Death and Birth by The 12th Gangri Karma RinpocheDocument28 pagesThe Bright Mind Between Death and Birth by The 12th Gangri Karma RinpocheAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.100% (1)

- Larungdailyprayerspracticespdf PDFDocument212 pagesLarungdailyprayerspracticespdf PDFBecze IstvánNo ratings yet

- 2009viennaheruka PDFDocument10 pages2009viennaheruka PDFAigo Seiga CastroNo ratings yet

- Melody of Dharma 13Document84 pagesMelody of Dharma 13hyakuuuNo ratings yet

- Jamme Tulku HistoryDocument6 pagesJamme Tulku HistoryEasy OkNo ratings yet

- RahulaDocument1 pageRahulaJohnathanNo ratings yet

- Autobiography Padmasambhava 12Document2 pagesAutobiography Padmasambhava 12CittamaniTaraNo ratings yet

- Prayer Magnetizes PDFDocument4 pagesPrayer Magnetizes PDFPohSiang100% (1)

- Of The Tibetan CultureDocument2 pagesOf The Tibetan CultureamirlandaNo ratings yet

- 123Document2 pages123Angela RosarioNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Prayer BookDocument98 pagesBuddhist Prayer BookRiwo GandenNo ratings yet

- Recommended ReadingsDocument3 pagesRecommended ReadingsRahul BalakrishanNo ratings yet