Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Quek Gin Hong V Public Prosecutor - (1998) 4

Uploaded by

norsiahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Quek Gin Hong V Public Prosecutor - (1998) 4

Uploaded by

norsiahCopyright:

Available Formats

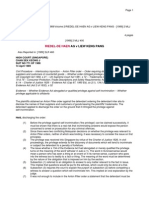

Page 1

Page 2

Malayan Law Journal Reports/1998/Volume 4/QUEK GIN HONG v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR - [1998] 4 MLJ

161 - 17 August 1998

7 pages

[1998] 4 MLJ 161

QUEK GIN HONG v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR

HIGH COURT (MELAKA)

SURIYADI J

CRIMINAL REVISION NO 42-17 OF 1997

17 August 1998

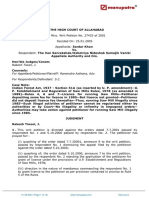

Criminal Law -- Environmental Quality (Clean Air) Regulations 1978 -- Allowing open burning without licence

-- Whether an offence known to law -- Environmental Quality (Clean Air) 1978 reg 12

Criminal Procedure -- Prosecution -- Right to conduct prosecution -- Director General granted powers to

prosecute at par with the Public Prosecutor -- Whether void for inconsistency with art 145(3) of the Federal

Constitution -- Environmental Quality Act 1974 s 44 -- Federal Constitution art 145(3) -- Criminal Procedure

Code (FMS Cap 6) s 422

The accused was charged for allowing open burning of certain vegetation waste without a licence contrary to

reg 12 of the Environmental Quality (Clean Air) Regulations 1978 ('the Regulations'). He was found guilty and

sentenced to six months' imprisonment. Counsel for the accused requested for a revision on the grounds

that: (i) s 44 of the Environmental Quality Act 1974 ('the Act') -- which provides for the prosecution of offences

under the Act by the Director General -- was ultra vires art 145(3) of the Federal Constitution; (ii) there was

no written authority to prosecute from the Public Prosecutor pursuant to s 377 of the Criminal Procedure

Code (FMS Cap 6) ('the CPC'); and (iii) he was charged for an offence which was unknown to law. A further

issue was whether s 422 of the CPC would save the sentence if there was want of authorization to

prosecute.

Held, setting aside the order and acquitting the accused:

1)

1)

1)

1)

Section 44 of the Act which endowed the Director General with powers at par with the Public

Prosecutor was void for inconsistency with art 145(3) of the Federal Constitution (see pp 164HI and 165A); Repco Holdings Bhd v PP [1997] 3 MLJ 681 followed. Therefore, any documented

authorization emanating from the Director General was worthless and would not validate any

shortcomings in the want of authority to prosecute (see p 165G-H).

Section 422(a) of the CPC was inapplicable in this case as it anticipated some form of error,

omission or irregularity in a sanction or consent that was earlier issued. Further, since nothing

was built into the Act which requireed a sanction similar to that of s 129 of the CPC, s 422(b)

was also inapplicable. Moreover, the amended s 422 may not save the case since the want of

authorization to prosecute had caused a failure of justice (see p 166E-I).

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 162

Regulation 12 of the Regulations does not create an offence as it merely lays down the factors

for the subjective consideration of the Director General prior to the granting of any licence to

carry out open burning. Even if this were not so, there was absolutely no evidence to connect

the accused with the ownership of the land or the cause of the fire (see pp 167G-I and 168AC).

In the normal course of events, for cases where the orders of judges were set aside on the

ground of nullity, the substitute orders would invariably be to discharge the accused persons

Page 3

not amounting to an acquittal. However, in this case, an order of acquittal would be appropriate

(see p 168E-G).

[Bahasa Malaysia summary

Tertuduh dipertuduhkan kerana membenarkan pembakaran terbuka sisa-sisa tumbuhan tertentu tanpa lesen

bertentangan dengan peraturan 12 Peraturan-Peraturan Kualiti Alam Sekeliling (Udara Bersih) 1978

('Peraturan tersebut'). Ia didapati bersalah dan dijatuhkan hukuman penjara selama enam bulan. Peguam

tertuduh meminta penyemakan atas alasan bahawa: (i) s 44 Akta Kualiti Alam Sekeliling 1974 ('Akta

tersebut') -- yang memperuntukkan pendakwaan kesalahan di bawah Akta tersebut oleh Ketua Pengarah -adalah ultra vires perkara 145(3) Perlembagaan Persekutuan; (ii) tiada kebenaran bertulis untuk mendakwa

daripada Pendakwa Raya menurut s 377 Kanun Acara Jenayah (NMB Bab 6) ('KAJ'); dan (iii) ia

dipertuduhkan untuk kesalahan yang tidak dikenali di sisi undang-undang. Isu lanjut adalah sama ada s 422

KAJ boleh menyelamatkan hukuman sekiranya terdapat kekurangan pemberikuasaan untuk mendakwa.

Diputuskan, mengetepikan perintah dan membebaskan tertuduh:

2)

2)

2)

2)

Seksyen 44 Akta tersebut yang mengurniakan Ketua Pengarah dengan kuasa yang selaras

dengan Pendakwa Raya adalah tak sah kerana tak konsisten dengan perkara 145(3)

Perlembagaan Persekutuan (lihat ms 164H-I dan 165A); Repco Holdings Bhd v PP [1997] 3

MLJ 681 diikut. Maka, sebarang pemberikuasaan berdokumentasi yang datang dari dari Ketua

Pengarah adalah tidak bernilai dan tidak akan menjadikan sah apa-apa kelemahan dalam

kegagalan pemberikuasaan untuk mendakwa (lihat ms 165G-H).

Seksyen 422(a) KAJ tidak terpakai dalam kes ini kerana ia menjangkakan kesilapan,

peninggalan atau luar aturan dalam sanksi atau kebenaran yang diberikan dahulu. Selanjutnya,

oleh kerana tiada apa-apa telah dimasukkan ke dalam Akta tersebut yang menghendaki sanksi

yang serupa dengan s 129 KAJ, s 422(b) juga tidak terpakai. Tambahan pula, s 422 yang

terpinda tidak menyelamatkan kes kerana kegagalan pemberikuasaan untuk mendakwa telah

menyebabkan kegagalan keadilan (lihat ms 166E-I).

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 163

Peraturan 12 Peraturan tersebut tidak mewujudkan suatu kesalahan kerana ia cuma

menyatakan faktor-faktor untuk pertimbangan subjektif Ketua Pengarah sebelum memberikan

apa-apa lesen untuk menjalankan pembakaran terbuka. Biarpun ini tidak dilakukan, tiada

keterangan langsung untuk mengaitkan tertuduh dengan pemilikan tanah atau punca

kebakaran (lihat ms 167G-I dan 168A-C).

Dalam keadaan biasa, untuk kes-kes di mana perintah hakim diketepikan atas alasan

pembatalan, perintah pengganti selalunya adalah untuk melepaskan tertuduh tidak terjumlah

kepada pembebasan. Namun demikian, dalam kes ini, suatu perintah pembebasan adalah

wajar (lihat ms 168E-G).]

Notes

For a case on right to conduct prosecution, see 5 Mallal's Digest (4th Ed, 1994 Reissue) para 2040.

Cases referred to

Abdul Hamid v PP [1956] MLJ 231 (refd)

Hassan bin Ishak v PP [1948-49] MLJ Supp 179 (refd)

Kyohei Hosoi v PP [1998] 1 CLJ 1063 (refd)

Lyn Hong Yap v PP [1956] MLJ 226 (refd)

Mohd Dalhar bin Redzwan & Anor v Datuk Bandar, Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur [1995] 1 MLJ 645 (refd)

Ng Song Luak v PP [1985] 1 MLJ 456 (refd)

Page 4

Periasamy & Anor v PP [1993] 2 MLJ 551 (refd)

R v Metz 11 Cr App R 164 (refd)

Repco Holdings Bhd v PP [1997] 3 MLJ 681 (folld)

R v Retnam [1934] MLJ 6 (refd)

Salleh and Husin v R (1908) 10 SSLR 27 (refd)

Legislation referred to

Criminal Procedure Code (FMS Cap 6) ss 129(3) 305 376(1) 377, (b)(3) 422, (a)

Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act 1998 (Act A1015)

Environment Quality Act 1974 ss 22(3) 44

Environmental Quality (Amendment) Act 1998 (Act A1030)

Environmental Quality (Clean Air) Regulations 1978 reg 12

Federal Constitution arts 4 145(3)

Low Kian Boon (JA Nathan & Co) for the accused.

Anselm Charles Fernandis (State Legal Advisor's Chambers) for the Public Prosecutor.

SURIYADI: J

The accused was supposed to have committed an offence on 20 September 1997, with a report filed against

him on 27 September

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 164

1997. He was later charged, and found guilty pursuant to a plea of guilt before the sessions court judge on

17 November 1997. He was thenceforth sentenced to six months imprisonment. For completeness, permit

me to reproduce the charge, which reads:

Bahawa kamu Quek Gin Hong pada 20 September 1997 jam lebih kurang 11.00 pagi di Lot DSPN 21, 24, 25, 26, 27

dan 28, Mukim Machap, Daerah Alor Gajah, di dalam Negeri Melaka, sebagai kontraktor, didapati tanpa lesen di bawah

s 22(1) Akta Kualiti Alam Sekitar 1974 telah membiarkan pembakaran terbuka terhadap bahan-bahan yang boleh

terbakar sisa-sisa tumbuhan) berlawanan dengan syarat yang boleh diterima di bawah peraturan 12 PeraturanPeraturan Kualiti Alam Sekeliling (Udara Bersih) 1978 dan boleh didenda di bawah s 22(3) Akta Kualiti Alam Sekeliling

(Pindaan) 1996.

Pursuant to s 305 of the Criminal Procedure Code (FMS Cap 6), an accused's right of appeal is limited only

to the extent and legality of the sentence. In compliance with this provision, the accused filed the notice of

appeal on 20 November 1997, as against the excessive severity of the sentence. On 26 January 1998, the

court received a letter from the accused's counsel, requesting for a revision in spite of having filed that

appeal. This route taken by the accused is not improper, as once an appeal has been lodged, the latter is not

prevented from contending that the conviction is illegal, and thenceforth request the judge to act in revision

(Mohd Dalhar bin Redzwan & Anor v Datuk Bandar, Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur [1995] 1 MLJ 645).

Having received that letter, and having understood the consternation of the accused's counsel, I accordingly

called up the file. On 17 August 1998 after hearing the case, I set aside the order and acquitted the accused.

I now give my reasons for that decision. In principle, there were three main grounds which persuaded me to

arrive that decision, namely:

3)

s 44 of the Environment Quality Act 1974 ('Act 127'), is ultra vires art 145(3) of the Federal

Constitution;

Page 5

3)

3)

there was no written authority to prosecute from the Public Prosecutor, pursuant to s 377 of the

Criminal Procedure Code; and

that he was charged for an offence under peraturan 12, Peraturan-Peraturan Kualiti Alam

Sekeliling (Udara Bersih) 1978, punishable under s 22(3) of the Akta Kualiti Alam Sekeliling

(Pindaan) 1996, offence which is unknown to law.

Built into the Environmental Quality Act 1974 is s 44 which provides for the power and conduct of the

prosecution. This provision reads:

Prosecutions in respect of offences committed under this Act or regulations made thereunder may be conducted by the

Director General or any officer duly authorized in writing by him or by any officer of any local authority to which any

powers under this Act has been delegated.

A simple reading of this provision, and without having to produce a lengthy dissertation of it, highlights

another glaring example of a Director General being endowed with powers at par with the Public Prosecutor.

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 165

I need only say that the power of prosecution is the exclusive domain of the Public Prosecutor, and as such

this provision is void for inconsistency, with art 145(3) of the Federal Constitution. Article 4 of the Federal

Constitution, in crystal clear terms, has provided that the Federal Constitution is the supreme law of the

Federation, and any law passed after Merdeka Day, which is inconsistent with this Constitution, to the extent

of the inconsistency, is void (PP v Chua Chor Kian [1998] 1 MLJ 167). For easy reference I reproduce art

145(3) of the Federal Constitution, which reads:

The Attorney General shall have power, exercisable at his discretion, to institute, conduct or discontinue any

proceedings for an offence, other than proceedings before a Syariah Court, a native court or a court-martial.

To streamline this article, it is further supplemented by s 376(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code which reads:

The Attorney General shall be the Public Prosecutor and shall have the control and direction of all criminal prosecutions

and proceedings under the Code.

To carry out his onerous and manifold functions smoothly, he may authorize certain officers to conduct the

prosecution, as provided for under s 377 of the Criminal Procedure Code, as amended by Act A1015. This

section reads:

Every criminal prosecution before any court and every inquiry before a Magistrate shall, subject to the following

sections, be conducted -...

(b) subject to the control and direction of the Public Prosecutor, by the following persons who are

authorized in writing by the Public Prosecutor:

...

(3) an officer of any Government department; ....

On the premise that the Director General is not conferred with the power to institute or conduct any

prosecution, then needless to say he is powerless to delegate authority, or for anyone else to prosecute on

his behalf. On that account, any documented authorization emanating from the Director General is worthless

and will not validate any shortcomings in the want of authority to prosecute. It must have dawned upon the

relevant authorities of the void in the sphere of prosecution, as Parliament subsequently promulgated the

Environmental Quality (Amendment) 1998 ('Act A1030'). In spite of the passing of that Act, as the relevant

Minister has yet to notify the effective date in the Gazette, the present s 44 with all the debilitating defects are

still left untouched in the statue, the amended s 44, for purposes of an academic discussion of the problem at

hand, reads:

Page 6

No prosecution shall be instituted for an offence under this Act or the regulations made thereunder without the consent

in writing of the Public Prosecutor.

This new amended provision will bring in line Act 127, with art 145(3) of the Federal Constitution and s 376 of

the Criminal Procedure Code, in

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 166

that future prosecutions by officers of the Environmental Department will be flawless. Any consent obtained

from the Public Prosecutor will entail deep consideration by the latter, as compared to a sanction. To quote

Smith J in Abdul Hamid v PP [1956] MLJ 231 at p 232 :

... full consideration is required for consent since 'consent' is an act of reason, accompanied with deliberation, the mind

weighing, as in a balance, good and evil on each side (1 Stroud (3rd Ed) at p 582).

On 1 April 1998, conservatively about six months after the accused was sentenced, the Criminal Procedure

(Amendment) Act 1998 ('Act A1015') came into effect. This latter Act amended the Criminal Procedure Code,

inter alia, s 422 which reads:

Subject to the provisions contained in this Chapter no finding, sentence or order passed or made by a Court of

competent jurisdiction shall be reversed or altered on account of -(a) any error, omission or irregularity on the complaint, sanction, consent, summons, warrant, charge,

judgment or other proceedings before or during trial or in any inquiry or other proceedings under this

Code;

(b) the want of any sanction; or

(c) the improper admission or rejection of any evidence,

unless such error, omission, irregularity, want, or improper admission or rejection of evidence has occasioned a failure

of justice.

For purposes of the current case, s 422(a) is inapplicable as it anticipates some form of error, omission or

irregularity in a sanction or consent (both statutorily provided to be in writing, eg a sanction must be in writing

as provided in s 129(3) of the Criminal Procedure Code; R v Retnam [1934] MLJ 6) that was earlier issued.

As none were issued by the Public Prosecutor, it is unnecessary for me to consider this subsection. Having

eliminated this subsection, the next provision left for consideration is sub-s (b) which is capable of saving the

court's sentence or order. Under the Criminal Procedure Code, the specific provision is s 129 of the Criminal

Procedure Code which lays down certain offences that require the sanction of the Public Prosecutor. It is

silent as to the requirement of sanction for other specific Acts. In brief, a sanction is an order directing the

prosecution of a certain person, and in the ordinary way, that order is conveyed to the authorities who are

responsible for initiating prosecution in the locality in question. Within the Environmental Quality Act 1974,

nothing is built into it which requires a sanction similar to that of s 129 of the Criminal Procedure Code. On

that score, s 422(b) of the Criminal Procedure Code is also inapplicable for the current case.

In spite of its draconian effect, this amended s 422 may not save completed flawed cases, if it occasions a

failure of justice. This amended section, as I see it, is no different from the views held by Hyndman-Jones CJ

in Salleh and Husin v R (1908) 10 SSLR 27, when his Lordship opined that the want of sanction or complaint

under the then s 135 of the Criminal Procedure Code did not vitiate a conviction, unless there was evidence

that a failure of justice had been occasioned. Without prejudging

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 167

the evidence, how could it not attract a failure of justice in this case, when the Public Prosecutor never even

had the opportunity to peruse the file. The Public Prosecutor was unaware of this prosecution, much to the

chagrin of the accused who had been deprived of his constitutional right. At the risk of repeating, injustice

had occurred here when:

4)

the prosecuting officer of the Environmental Quality Department did not possess the written

authorization from the Public Prosecutor, pursuant to s 377(b)(3) of the Criminal Procedure

Code. It must be stressed that the letter of authorization pursuant to s 377(b) is not of the same

Page 7

4)

4)

3)

strength and quality as a sanction pursuant to s 129 of the Criminal Procedure Code which

requires due consideration by the Public Prosecutor (Salleh and Husin v R);

the Public Prosecutor was totally oblivious to the prosecution, and never had the opportunity to

peruse and decide on the viability of the prosecution. If the accused had the priviledge of the

highest placed legal brain in the country perusing the investigation papers, he might not even

have been charged. A perusal of the notes of the proceeding will confirm that he had been

deprived of relevant substantive legal protection devised by law, for a person who is supposed

to be innocent before being found guilty;

the initiation of the prosecution of the accused was pursuant to a provision ultra vires the

Constitution. This was not a case of a person charged after having received the concurrence of

the Public Prosecutor, subsequently flawed by technicalities, but a prosecution founded on

illegality from the beginning (Lyn Hong Yap v PP [1956] MLJ 226; R v Metz 11 Cr App R 164.

See the case of Hassan bin Ishak v PP [1948-49] MLJ Supp 179 where Pretheroe ACJ as

regards the matter on trial, opined that in the absence of the sanction of the Public Prosecutor

the proceedings at the lower courts were null and void); and

the factor of being charged under reg 12 which does not create an offence (Periasamy & Anor

v PP [1993] 2 MLJ 551). For clarification, I reproduce reg 12 which reads:

A licence to carry out open burning may be granted if the Director General is satisfied that -(i) open burning is the only economically practicable method of disposal; and

(ii) such open burning is not likely to cause pollution. This is a provision that lays

down the factors for the subjective consideration of the Director General prior to the

granting of any licence. There is no reference under this provision to the ingredient of

'membiarkan pembakaran terbuka terhadap bahan-bahan yang boleh terbakar sisasisa tumbuhan) berlawanan dengan syarat yang boleh diterima di bawah peraturan

12'. In the event this expression of 'membiarkan pembakaran terbuka' falls within the

ambit of the words 'cause' (menyebabkan), 'allow'

1998 4 MLJ 161 at 168

(membenarkan/membiarkan) and 'permit' (mengizinkan), all these words involve

power and rights. To exercise all these powers, and fall within the ambit of these

words, the offender must be the owner of the material land or a person having

acquired the powers of the owner. In open court, I was informed in no uncertain

terms that the accused was not the owner of the land. The report and the facts of the

case are silent as to that fact or of the accused's relationship with the land and the

fire. Since there was absolutely no evidence to connect the accused with those two

factors, I was therefore dissuaded from framing a charge based on reg 11 of the

Environmental Quality (Amendment) Act 1996 (Ng Song Luak v PP [1985] 1 MLJ

456).

As s 44 of the Environmental Quality Act is ultra vires the Constitution, with s 422 of the Criminal Procedure

Code being inapplicable for the current case, I was therefore guided and bound by Repco Holdings Bhd v PP

[1997] 3 MLJ 681. In that case, the prosecution was also invalidated due to the want of authority to prosecute

from the Public Prosecutor. In this case, by analogy as no authorization was obtained from the Public

Prosecutor, this prosecution therefore was illegal (see also Kyohei Hosoi v PP [1998] 1 CLJ 1063). Pursuant

to all the above reasons, I acquitted and discharged the accused. As much as the country is being beset by

atmospheric pollution, and spearheaded by every responsible department to ensure that the haze does not

rear its ugly head again, the law and rights of individuals must not be compromised. In the normal course of

events, for cases where the orders of judges are set aside on ground of nullity, the substitute orders will

invariably be to discharge the accused persons not amounting to an acquittal. In this case, the Public

Prosecutor could not be said to be interested in the prosecution, as the case was never even within his

knowledge in the first place, no fault of his. Reverting to the predicament of the accused, had it not been for

this revision, he would now be deprived of six months of freedom, due to the infringement of his constitutional

rights. Having gone through the turmoil of uncertainty, brought about by an illegal prosecution, let alone a

charge that will not stand, this order therefore would be an appropriate one.

Page 8

Accused acquitted and discharged.

Reported by Loo Lai Mee

You might also like

- Jumari Bin Mohamed V PPDocument3 pagesJumari Bin Mohamed V PPWestNo ratings yet

- DATUK HAJI HARUN BIN HAJI IDRIS v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR - Land Approval Corruption CaseDocument43 pagesDATUK HAJI HARUN BIN HAJI IDRIS v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR - Land Approval Corruption CaseSuhail Abdul Halim67% (3)

- Majlis Peguam Malaysia v. Rajehgopal Velu & AnorDocument22 pagesMajlis Peguam Malaysia v. Rajehgopal Velu & AnorSheera StarryNo ratings yet

- Mentri Besar Corruption Conviction AppealDocument59 pagesMentri Besar Corruption Conviction AppealAmir SyafiqNo ratings yet

- Drug Treatment Court Order AppealDocument6 pagesDrug Treatment Court Order AppealChee KianNo ratings yet

- SUPREME COURT RULINGDocument6 pagesSUPREME COURT RULINGMohamad MursalinNo ratings yet

- ST Martin Funeral Homes V NLRCDocument12 pagesST Martin Funeral Homes V NLRCIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Riedel-De Haen Ag V Liew Keng Pang - (1989)Document7 pagesRiedel-De Haen Ag V Liew Keng Pang - (1989)mykoda-1No ratings yet

- Supreme Court of India reviews Bhopal gas tragedy settlementDocument86 pagesSupreme Court of India reviews Bhopal gas tragedy settlementSri MuganNo ratings yet

- Abdul GhaffarDocument6 pagesAbdul GhaffarlaiyyeenNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of India Reviews Bhopal Gas Tragedy SettlementDocument99 pagesSupreme Court of India Reviews Bhopal Gas Tragedy SettlementRaj ChouhanNo ratings yet

- FEMA Appeal Remedy Writ BarredDocument11 pagesFEMA Appeal Remedy Writ BarredNitin SherwalNo ratings yet

- 1992 S C M R 241Document8 pages1992 S C M R 241Taimour Ali Khan MohmandNo ratings yet

- Public Prosecutor V Muhari Bin Mohd JaniDocument16 pagesPublic Prosecutor V Muhari Bin Mohd JaniHezekiah TanNo ratings yet

- Kidnapping Act 1961 - Child witness evidence and voluntariness of statementsDocument24 pagesKidnapping Act 1961 - Child witness evidence and voluntariness of statementsmerNo ratings yet

- Rhina Bhar v. Koid Hong KeatDocument10 pagesRhina Bhar v. Koid Hong KeatAmira NadhirahNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Bar Q&A - From JomelDocument9 pagesAdmin Law Bar Q&A - From Jomelsei1davidNo ratings yet

- This Judgement Ranked 1 in The Hitlist.: 2001 (1) Curlj (CCR) 182Document35 pagesThis Judgement Ranked 1 in The Hitlist.: 2001 (1) Curlj (CCR) 182GURMUKH SINGHNo ratings yet

- 2002_10_25_2002_4_CLJ_547_PAI_SAN_V_PP_EDDocument13 pages2002_10_25_2002_4_CLJ_547_PAI_SAN_V_PP_EDIlias YeeNo ratings yet

- Rakesh Tiwari, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2005 3 AWC 2843allDocument10 pagesRakesh Tiwari, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2005 3 AWC 2843allTags098No ratings yet

- TENGKU ALI IBNI ALMARHUM SULTAN ISMAIL V KERDocument6 pagesTENGKU ALI IBNI ALMARHUM SULTAN ISMAIL V KERviveka86No ratings yet

- Lee Cheng Yee (Suing As Administrator of The Estate of Chia Miew Hien) V Tiu Soon SiangDocument5 pagesLee Cheng Yee (Suing As Administrator of The Estate of Chia Miew Hien) V Tiu Soon SiangEden YokNo ratings yet

- Mohanlal Shamji Soni Vs Union of India UOI and Ors1110s910181COM206847Document10 pagesMohanlal Shamji Soni Vs Union of India UOI and Ors1110s910181COM206847Geetansh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Suits by Indigent Persons 1Document11 pagesSuits by Indigent Persons 1Mythili100% (1)

- RP vs. RosemoorDocument10 pagesRP vs. RosemoorDennis VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Aizuddin Syah Bin Ahmad V Public ProsecutorDocument8 pagesAizuddin Syah Bin Ahmad V Public ProsecutorFateh ArinaNo ratings yet

- 162226Document6 pages162226The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeNo ratings yet

- Judgment: Signature Not VerifiedDocument9 pagesJudgment: Signature Not VerifiedMohammad Fariduddin100% (1)

- Para 13-Limba - Jaya (Former Federal Court Higher Hierachy Than Present Court of Appeal) PDFDocument10 pagesPara 13-Limba - Jaya (Former Federal Court Higher Hierachy Than Present Court of Appeal) PDFWong Xian ZhengNo ratings yet

- 1990 M L D 588Document8 pages1990 M L D 588m. Hashim IqbalNo ratings yet

- AdminDocument6 pagesAdminDiggerNo ratings yet

- Admin Bar QuestionsDocument11 pagesAdmin Bar QuestionsaceamulongNo ratings yet

- Union Carbide Corporation Etc Vs Union of India Etc Etc On 3 October 1991Document100 pagesUnion Carbide Corporation Etc Vs Union of India Etc Etc On 3 October 1991YUVRAJ DEBAPRIYA MITRANo ratings yet

- HJ Ahmad Ragib Bin HJ Mohd Salleh 3 LagiDocument17 pagesHJ Ahmad Ragib Bin HJ Mohd Salleh 3 LagiMoon Nieyra100% (1)

- LAW 471-CPC - Civil Procedure Code-09Document14 pagesLAW 471-CPC - Civil Procedure Code-09Mehmood AslamNo ratings yet

- Vineland Chemical Co., Inc. v. United States Environmental Protection Agency, 810 F.2d 402, 3rd Cir. (1987)Document12 pagesVineland Chemical Co., Inc. v. United States Environmental Protection Agency, 810 F.2d 402, 3rd Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- C.P. 116 2020Document6 pagesC.P. 116 2020Muhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 99Document99 pagesSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 99puneet0303No ratings yet

- Absolute Liability Case, Bhopal Gas LeakDocument11 pagesAbsolute Liability Case, Bhopal Gas LeakTarik ul KabirNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs Rosemoor Mining and Development Corporation - GR 149927 - March 30, 2004Document9 pagesRepublic Vs Rosemoor Mining and Development Corporation - GR 149927 - March 30, 2004BerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoNo ratings yet

- DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE V THE PRSIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA & OTHERSDocument50 pagesDEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE V THE PRSIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA & OTHERSAngelo De SousaNo ratings yet

- Dato' Seri Anwar Bin Ibrahim V Pendakwa RayaDocument24 pagesDato' Seri Anwar Bin Ibrahim V Pendakwa RayaDeena YosNo ratings yet

- St. Martin Funeral Homes Vs NLRCDocument9 pagesSt. Martin Funeral Homes Vs NLRClawdiscipleNo ratings yet

- SAR Decision on Costs UpheldDocument4 pagesSAR Decision on Costs UpheldAlae KieferNo ratings yet

- Oldwick Materials, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 732 F.2d 339, 3rd Cir. (1984)Document6 pagesOldwick Materials, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 732 F.2d 339, 3rd Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rourkela Steel Plant seeks recall of arbitration orderDocument194 pagesRourkela Steel Plant seeks recall of arbitration orderAnonymous NARB5tVnNo ratings yet

- Vellama V AG (2013)Document40 pagesVellama V AG (2013)Anonymous h5pR4JNo ratings yet

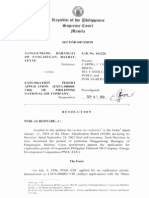

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court ManilaDocument15 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court ManilajdzoeNo ratings yet

- Abd Razak Bin AtanDocument22 pagesAbd Razak Bin AtanElisabeth ChangNo ratings yet

- S 173 (A) - (M)Document50 pagesS 173 (A) - (M)Salma AlinaNo ratings yet

- REPUBLIC of The PHILIPPINES, Represented by The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)Document14 pagesREPUBLIC of The PHILIPPINES, Represented by The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)tops videosNo ratings yet

- Air Philippines CorporationDocument17 pagesAir Philippines Corporationjagalamayjrcpagmail.comNo ratings yet

- DENR vs PICOP ResourcesDocument9 pagesDENR vs PICOP Resourcesgilbert213No ratings yet

- Bar Questions in Administrative Law From 1989Document27 pagesBar Questions in Administrative Law From 1989Solomon Malinias BugatanNo ratings yet

- Maceda Vs Energy Regulatory BoardDocument15 pagesMaceda Vs Energy Regulatory BoardJan Igor GalinatoNo ratings yet

- Efforts To Make CPC More Justice-OrienteDocument15 pagesEfforts To Make CPC More Justice-OrienteSaharsh ChitranshNo ratings yet

- Bar Questions in Administrative Law From 1989 DDDocument27 pagesBar Questions in Administrative Law From 1989 DDLiu HaikuanNo ratings yet

- Erectors Inc. V NLRCDocument4 pagesErectors Inc. V NLRCMelgenNo ratings yet

- Role ModelsDocument1 pageRole ModelsnorsiahNo ratings yet

- New Collection Design Empowers WomenDocument26 pagesNew Collection Design Empowers WomennorsiahNo ratings yet

- Summary 2Document2 pagesSummary 2norsiahNo ratings yet

- How To Answer Law QuestionDocument1 pageHow To Answer Law QuestionnorsiahNo ratings yet

- CONSUMER AND BUSINESS MARKETING FACTORSDocument21 pagesCONSUMER AND BUSINESS MARKETING FACTORSnorsiahNo ratings yet

- 2011 Gloria Jeans Coffee in MalaysiaDocument8 pages2011 Gloria Jeans Coffee in Malaysianorsiah0% (1)

- Introduction to Waqf ConceptDocument2 pagesIntroduction to Waqf ConceptnorsiahNo ratings yet

- Offer and AcceptanceDocument94 pagesOffer and AcceptancenorsiahNo ratings yet

- Noura Dates SDN BHDDocument11 pagesNoura Dates SDN BHDnorsiahNo ratings yet

- Supply ChainDocument3 pagesSupply ChainnorsiahNo ratings yet

- ProtonDocument6 pagesProtonnorsiah100% (2)

- ReferencesDocument1 pageReferencesnorsiahNo ratings yet

- Rahsia Kelahiran Ikut BulanDocument12 pagesRahsia Kelahiran Ikut BulannorsiahNo ratings yet

- TWG Tea Case StudyDocument2 pagesTWG Tea Case Studynorsiah100% (1)

- Google Case Study AnswerDocument2 pagesGoogle Case Study Answernorsiah83% (12)

- Theory of LearningDocument8 pagesTheory of LearningnorsiahNo ratings yet

- The Early RetirementDocument1 pageThe Early RetirementnorsiahNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Fm1Document2 pagesTutorial Fm1norsiahNo ratings yet

- Pastyearsattempt2 120105121211 Phpapp02Document3 pagesPastyearsattempt2 120105121211 Phpapp02norsiahNo ratings yet

- SC refuses stay on CAA, UN voices concern over discriminatory lawDocument4 pagesSC refuses stay on CAA, UN voices concern over discriminatory lawsimran yadavNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 2-Syllabus-UST (February 2018)Document12 pagesConstitutional Law 2-Syllabus-UST (February 2018)isaafabian100% (2)

- Goyanko Vs UCPB 690s79Document9 pagesGoyanko Vs UCPB 690s79Norma Waban100% (1)

- Concepts of Constitution, Constitutional Law, and ConstitutionalismDocument6 pagesConcepts of Constitution, Constitutional Law, and Constitutionalismكاشفة أنصاريNo ratings yet

- LIMBONA Vs MANGELINDocument2 pagesLIMBONA Vs MANGELINGianna de Jesus50% (2)

- Non vs. Judge DamesDocument2 pagesNon vs. Judge DamesStefanRodriguezNo ratings yet

- Functions of the Judicial BranchDocument23 pagesFunctions of the Judicial BranchLeah Joy Valeriano-QuiñosNo ratings yet

- Corporate and Business Law Exam Guide (MalaysiaDocument17 pagesCorporate and Business Law Exam Guide (MalaysiaDineshnaraindra SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Cyber Appellate Tribunal Hearing on Defamatory EmailsDocument25 pagesCyber Appellate Tribunal Hearing on Defamatory Emailspankaj_pandey_21No ratings yet

- Judicial Review-Leave Finsac Mangatal J.Document37 pagesJudicial Review-Leave Finsac Mangatal J.Coolbreeze45No ratings yet

- Civil Code Law Case DigestsDocument37 pagesCivil Code Law Case DigestsArmstrong BosantogNo ratings yet

- People'S Small-Scale Mining Act of 1991 (Republic Act No. 7076)Document2 pagesPeople'S Small-Scale Mining Act of 1991 (Republic Act No. 7076)ApureelRoseNo ratings yet

- Judge Sues DCA For Fixing CasesDocument21 pagesJudge Sues DCA For Fixing CasesRobert LedermanNo ratings yet

- Patent NotesDocument9 pagesPatent NotesmanikaNo ratings yet

- ANC ConstitutionDocument20 pagesANC Constitutionanyak1167032No ratings yet

- Tahanan Devp Vs CA G.R. No. L-55771Document7 pagesTahanan Devp Vs CA G.R. No. L-55771Arlene Taba FerrerNo ratings yet

- 81 Manantan vs. CADocument4 pages81 Manantan vs. CAGlomarie GonayonNo ratings yet

- Review PetitionDocument19 pagesReview PetitionshwetaNo ratings yet

- Crim Book 2 CasesDocument185 pagesCrim Book 2 CasesChard CaringalNo ratings yet

- Self-Governed Student Organization Agreement: IUB Fraternity and Sorority AddendumDocument4 pagesSelf-Governed Student Organization Agreement: IUB Fraternity and Sorority AddendumThe College FixNo ratings yet

- Simple Wedding Package (Miranty & Ivan)Document4 pagesSimple Wedding Package (Miranty & Ivan)Awang Smesco BRPNo ratings yet

- Ethics SW5Document24 pagesEthics SW5Claude CaduceusNo ratings yet

- Criminal RICO Manual For Federal ProsecutorsDocument551 pagesCriminal RICO Manual For Federal ProsecutorsJohn ReedNo ratings yet

- Bustamante Vs NLRCDocument6 pagesBustamante Vs NLRCCeline Sayson BagasbasNo ratings yet

- Manifest Partiality and Unwarranted BenefitsDocument3 pagesManifest Partiality and Unwarranted Benefits'William AltaresNo ratings yet

- The July Sky Consignment PacketDocument3 pagesThe July Sky Consignment PacketIndie RockNo ratings yet

- The New Jewish Wedding by Anita DiamantDocument39 pagesThe New Jewish Wedding by Anita DiamantSimon and Schuster27% (15)

- Chapter 2Document7 pagesChapter 2jonathan_hoiumNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Challenges in Civic EducationThe title "OVERCOMING CHALLENGES IN CIVIC EDUCATIONDocument68 pagesOvercoming Challenges in Civic EducationThe title "OVERCOMING CHALLENGES IN CIVIC EDUCATIONDøps Maløne100% (11)

- Contractor Appointment FormDocument3 pagesContractor Appointment FormRaymond Philip McConvilleNo ratings yet