Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TUUKKA KAIDESOJA - Exploring The Concept of Causal Power in A Critical Realist Tradition

Uploaded by

xxxxdadadOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TUUKKA KAIDESOJA - Exploring The Concept of Causal Power in A Critical Realist Tradition

Uploaded by

xxxxdadadCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 37:1

00218308

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a

Critical Realist Tradition

Tuukka

Original

Exploring

Kaidesoja

Article

the

of Social

Causal

Power in a Critical Realist

Tradition

Blackwell

Oxford,

Journal

JTSB

0021-8308

XXX

The Executive

UK

for

Publishing

theConcept

Theory

Management

Ltd

of

Committee/Blackwell

Behaviour

Publishing

Ltd. 2007

TUUKKA KAIDESOJA

the

This

ABSTRACT

transcendental

concept

article analyses

of account

emergence

andofevaluates

the

should

concept

be

theincorporated

ofuses

causal

of the

power

concept

to any

are examined.

adequate

of causal notion

power

Moreover,

in

of the

causal

it iscritical

argued

power.

realist

that

The

the

tradition,

concept

applications

which

of emergence

isofbased

the concept

onused

Royofin

Bhaskars

causal

Bhaskar

power

philosophy

andtoother

mental

of

critical

science.

powers,

realists

The

reasons,

works

concept

and

is of

social

shown

causal

structures

topower

be ambiguous.

that

in the

appears

critical

It isinrealist

also

the early

pointed

social

works

ontology

out of

that

Rom

are

theHarr

problematic.

concept

andofhiscausal

The

associates

paper

power

shows

isshould

compared

howbe

these

analysed

to Bhaskars

problems

in an

account

might

anti-essentialist

beofavoided

this concept

without

way. and

Ontological

giving

its uses

up the

and

in the

concept

methodological

critical

of realist

causalsocial

problems

power.ontology.

that vitiate

It is argued

Bhaskars

that

INTRODUCTION

The historical origins of the philosophical concept of causal power are traceable

to everyday language concepts such as ability, capacity, and readiness. In the

Western philosophical tradition, one of the earliest systematic treatments of this

concept can be found in Aristotles philosophy; his concept of efficient cause can

be seen as an ancestor of the modern concept of causal power. Efficient cause

is, however, only one of the four types of causes (or causal explanations) in

Aristotles classification of them. The others are formal, material, and teleological

cause. From this perspective, it is rather surprising that many current advocates

of the concept of causal power tend to see the variable causal powers of things as

the only kind of causes there is. This assumption is also largely accepted in the

critical realist tradition based on Roy Bhaskars philosophy of science. As is well

known, Bhaskar espoused the concept of causal power along with some other

ideas from Rom Harr, who was his teacher in philosophy. Therefore, the roots

of this concept in the critical realist tradition can be found in the early works of

Harr and his associates (e.g. E.H. Madden, P.F. Secord).

For the sake of clarity, it is useful to distinguish the ontological problem of

causality from the epistemological problem. The former problem concerns the

question: what is causation? A solution of this problem should specify, among

other things, the differentiating characteristics of causal relations from other kind

of relations. I agree with critical realists that the concept of causality cannot be

eliminated from any viable ontology and that the ontological problem of causality

is therefore a genuine one. The latter problem, by contrast, deals with the question:

how is it possible to acquire knowledge concerning causal relations? Here, we are

interested in the empirical identification of causal relations and empirical testing

of hypotheses and explanatory theories that putatively refer to causal relations and

causal mechanisms. Nevertheless, the ontological and the epistemological problems

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007. Published by Blackwell

Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

64

Tuukka Kaidesoja

of causality are not entirely independent, as our solution to one of them constrains the domain of possible solutions to the other.

The concept of causal power in the critical realist tradition is designed to address

the ontological problem of causality. Critical realists commonly believe that, in order

to develop adequate epistemological and methodological views, ontological questions must be answered first. Following this order of exposition, I herein analyse

and evaluate the uses of the concept of causal power in this tradition mainly from

the ontological point of view, although I also have occasionally something to say

about the epistemological and methodological implications of these uses as well.

I begin by investigating Harr and E.H. Maddens Causal Powers (CP), in which

they present a detailed analysis of the concept of causal power. Then I examine

the doctrine of human powers that Harr and P.F. Secord put forward in their

book, The Explanation of Social Behaviour (ESB). There is, however, somewhat a

controversial issue as to whether these two books be classified as belonging to the

tradition of critical realism or not. Be this as it may, these books have certainly

been influential in the formation of Bhaskars early philosophy of science and the

critical realist concept of causal power. Indeed, I also attempt to show that some

of the problems that vitiate the applications of the concept of causal power in

Bhaskar and other critical realists works already appear in CP and ESB. Furthermore, I point out that there are also some interesting contrasts between the

concept of causal power found in Harr and his associates early works and the

concept of causal power that is developed in the works of Bhaskar and other

critical realists (e.g. lack of the concept of emergence in CP and ESB). Next, I

turn my attention to Bhaskars first book, A Realist Theory of Science (RTS). I argue

that his transcendental account of the concept of causal power is both ontologically

and methodologically problematic. I also show that his version of the concept of

emergent causal power is ambiguous. Finally, I examine how the concept of

causal power is used in the critical realist social ontology that was first articulated

in Bhaskars book, The Possibility of Naturalism (PN). In this context, I also briefly

address the criticism that Harr and Charles C. Varela (e.g. 1996) raise against

applying the concept of causal power to social structures in the critical realist

social ontology. Although I largely accept their criticism, I nevertheless argue that

the concept of emergent causal power might be applied in a certain way to the

system-level properties of certain kind of concrete social systems. I also try to show

that the relations between the structure of the concrete social system and its

component agents may be considered as causal on the condition that we give up the

idea that there is only one adequate ontological analysis of the concept of causality.

HARR AND MADDEN ON THE CONCEPT CAUSAL POWER

In recent discussions dealing with critical realism, it is sometimes forgotten that

Harr (e.g. 1970) already uses the concept of causal power in the late sixties and

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

65

early seventies. However, the most detailed analysis of this concept in Harrs

works can be found in CP, which he wrote jointly with E.H. Madden. I think that

the analysis presented in CP is compatible with Harrs earlier accounts of this

concept and for this reason I focus, in this section, on the analysis of the concept

of causal power that was put forward in CP.

According to Harr and Madden, the concept of causal power adequately

represents the metaphysics presupposed by modern natural sciences. They contend that the world studied by natural sciences should not be understood as

merely consisting of passive matter in motion, or regularly conjoined atomistic

events, but rather of causally interacting powerful particulars. They argue that

these powerful particulars generate the observable patterns of events and the

nomic regularities. Furthermore, Harr and Madden argue that powerful

particulars possess essential natures in virtue of which they each necessarily

possess a certain ensemble of powers. They also maintain that, in certain

conditions, the powers of a certain powerful particular manifest themselves in

observable effects necessarily. Examples of such powerful particulars include fields

of potentials, chemical substances, ordinary material objects, and biological

organisms.

Harr and Madden (1975, 86) analyse the ascription of causal power to a thing

as follows: X has the power to A means X (will)/(can) do A, in the appropriate

conditions, in virtue of its intrinsic nature. In other words, causal powers are

properties of concrete powerful particulars, which they possess in virtue of their

natures. One consequence of this analysis is that abstract entities such as numbers,

moral values, meanings, and social classes cannot possess causal powers. However,

the term can incorporated into the previous analysis is meant to secure the

extension of this analysis to the ascription of causal powers to people (ibid. 87).

I will come back to this extension later. By the concept of intrinsic nature, Harr

and Madden (e.g. ibid. 101102) refer to the real essences of powerful particulars.

These real essences are constitutions or structures of particular things in virtue of

which they each posses a certain ensemble of causal powers. They also believe

that it is, in principle, possible to divide objects of natural scientific research into

natural kinds according to their real essences (ibid. 1618, 102).

An important feature of Harr and Maddens account of causality is that they

conceive the relationship between the occasion for the exercise of the certain

power and the manifestations of that power in observable effects as naturally

necessary (ibid. 5). They state that; [t]he ineliminable but non-mysterious powers

and abilities of particular things [ . . . ] are the ontological ties that bind causes

and effects together (ibid. 11). The natural necessity that connects causes to their

effects in causal relations is, according to this view, a real feature of the world

and not a feature that the mind has somehow projected onto reality. Harr and

Madden also argue that the relationship between the ensemble of causal powers

of a powerful particular and that its essential nature is naturally necessary and,

therefore, they also contend that it is physically impossible for a powerful particular

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

66

Tuukka Kaidesoja

to act or react incompatibly with its own nature (ibid. 1314). Furthermore,

Harr and Madden (ibid. 1921) distinguish the concept of natural necessity

from the concepts of logical, transcendental, and conceptual necessity. They

nevertheless maintain that the conceptual necessity embedded in our historically

developed conceptual systems may reflect a natural necessity grounded in the

essential natures of things when empirical knowledge, acquired via scientific

research into these natures, is used in real definitions of natural kinds (ibid. 67,

1214, 1618). It follows from this that the propositions describing natural necessities are different from the logically necessary propositions, because the former

are necessarily a posteriori and the latter a priori.

Harr and Maddens notion of natural necessity is compatible with our common sense intuitions concerning causal relations. We do believe, for example, that

it is somehow necessary that a sample of water boils in normal air pressure when

heated to 100C by virtue of its chemical structure (i.e. H2O molecules interacting

in certain ways). Harr and Madden use these kinds of intuitions heavily when

they try to establish the superiority of their position to that of Human regularity

theory, which, according to their interpretation, reduces causal relations to the

constant conjunctions of observable events and denies the existence of the natural

necessities. It is not, however, entirely clear whether Harr and Maddens theory

is in fact an adequate ontological analysis of the concept of causality. For example,

Raymond Woller (1982) argues that this theory is problematic since Harr and

Maddens treatment of the concept of natural necessity is multifarious even

though they use it as it were unified. I propose that there is indeed some wavering

in their use of this concept, but I also contend (contra Woller) that its different

uses are quite tightly related to the two main uses previously mentioned. Be this

as it may, I also suggest that their analysis of the concept of causal power is

problematic or is at least insufficient in other ways.

To picture this more clearly, we need to think of some complex material thing,

say a eukaryote cell, which can be decomposed into parts (e.g. organelles), which

are also complex things that can be further broken down into parts (e.g. organic

molecules) and so forth. Now, it may be asked: what is the intrinsic nature (or

structure) of the eukaryotic cell in virtue of which it necessarily possesses a certain

ensemble of causal powers? If the causal powers of this cell are ontologically

dependent on the non-relational powers of its component organelles, in the sense

that the powers of the cell do not exist unless the powers of its organelles exists,

as it is reasonable to assume, then it may be asked: are the powers possessed by

the cell nothing but the ontological resultants (or mereological sums) of the non-relational powers

of its component organelles? If this is the case, then the powers of the cell are not

ontologically grounded in the nature of the cell, but rather in the natures of its

component organelles due to the fact that the powers of the cell can be ontologically reduced to the powers of its component organelles (i.e. in the last analysis

they are nothing but the resultants of the powers of the organelles). If we assume

for a moment that this view is correct, then it implies, methodologically, that it is,

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

67

in principle possible, to explain the properties of the cell solely by investigating

the non-relational causal powers of its component organelles without considering

their specific and complex organisation (e.g. their non-linear, complex, and

relatively permanent dynamic relationships). If the causal powers of the organelles

are also nothing but the resultants of the powers of their components, then this

ontological reduction can be repeated by reducing their causal powers in a similar

way to the powers of their component organic molecules. The same applies to

the powers of the organic molecules, which can be again reduced ontologically to

the powers of the atoms that constitute them. If the causal powers of the eukaryote

cell and its component organelles, and the component molecules of these component organelles and so forth, are all merely the ontological resultants of the

casual powers of their components, then this regression may go on ad infinitum or

it may stop to such ultimate entities that are plain powers which lack intrinsic

natures or structures. In either case, complex things such as an eukaryote cell are

not able perform any real causal work because, according to this interpretation,

their alleged causal powers are always ontologically reducible to the causal powers

of entities that are ontologically more fundamental.1

It seems to me that Harr and Madden are not ready to accept this ontologically

reductionist analysis of the concept of causal power, which I find problematic.

There are, for example, many passages in CP where they suggest that the specific

organisation of the parts (or structure) of a certain complex thing such as a water

molecule, a biological organism, or a car is somehow relevant regarding the

existence of the causal powers of this thing, although they admit that the powers

of these kinds of complex things are ontologically dependent on the powers of

their parts (e.g. ibid. 56, 104105). They also maintain that the explanation of

a certain power of a certain thing, in terms of its nature, does not explain this

power away nor eliminate the description of it from our description of this thing

(ibid. 11; see also Harr 1986, 285286). As such, it seems to me that Harr and

Madden at least implicitly commit to such a non-reductionist ontological view,

according to which the causal powers of complex things are not ontologically

reducible to the powers of their components. They fail, however, to provide any

sufficient clarification of this position or arguments for it and, consequently, do

not succeed in justifying this position. I think that one possible way to clarify and

defend this position is to introduce the notion of an emergent causal power that

specifies the conditions in which complex material things possess emergent causal

powers that are ontologically irreducible to the powers of their components, and

to provide empirical evidence for the existence of such emergent powers. Among

others, Bhaskar (1978) has developed a concept of emergent causal power, but,

as I will later argue, it is ambiguous and does not meet the previously stated

requirement. Nevertheless, I believe that an adequate concept of emergent causal

power might be incorporated to Harr and Maddens analysis of the concept of

causal power quite easily, although this is not the right place develop such a

concept.2

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

68

Tuukka Kaidesoja

Harr and Madden (ibid. 8687) emphasise that the powers of a certain

powerful particular do not cease to exist outside the conditions where they are

exercised as long as the nature of the particular does not change. Therefore,

according to their view, causal powers should be conceived as causal potencies of

things, which determine what the thing will, or can, do in the appropriate

conditions, rather than the empirical consequences of the exercise of these

powers. This marks the distinction between Harr and Maddens concept of causal

power and reductive analyses of dispositional concepts by using the hypothetical

or conditional statements presented by Gilbert Ryle and others. In other words,

Harr and Madden maintain that the causal powers of things cannot be ontologically reduced to their non-dispositional categorical properties. It is worth noting

that this position is different from the position considered in the previous section,

according to which, the causal powers of a complex thing cannot be reduced

ontologically to the powers of its components.

Harr and Madden (ibid. 8788) distinguish enabling conditions from stimulus

conditions for the exercise of a certain causal power of a powerful particular.

Satisfaction of the enabling conditions ensures that the powerful particular is of

the right nature and in the right state for the exercise of a certain power (ibid.

88). Therefore, the descriptions of enabling conditions refer to the intrinsic structure or constitution of the powerful particular. Harr and Madden also separate

the intrinsic structure of a particular thing from its internal structure, conceived

in a spatial sense, because the former may include some of the particulars relations to its external environment. Satisfaction of the stimulus conditions means,

by contrast, that a certain causal power of the powerful particular (that is already

in the state of readiness) is exercised. In other words, satisfaction of the stimulus

conditions will necessarily lead to the empirical manifestation of the power in

question, if no interfering influences are present.

Furthermore, Harr and Madden (ibid.) distinguish many kinds of causal

powers. These include active powers, passive powers or liabilities, constant powers,

variable powers, ultimate powers, tendencies, abilities, and capacities. Although it

is not necessary to consider these conceptual distinctions in detail here, the

question should be asked: do these various causal powers share a common core?

It seems to me that the answer is negative due to the fact that Harr and Madden

explicitly use at least two rather different conceptions of causal power (see Woller

1982, 627631). They apply the previously presented concept of causal power

to complex things with intrinsic natures. The other concept of causal power

appears in the context of a discussion on the nature of ultimate entities (see ibid.

161185). They state, for example, that; since the natures of ultimate entities are

their powers, no further characterisation of such particulars is possible, because

there is no independent question as to their natures (ibid. 162). Unlike the former,

this latter concept conflates the powers and natures of powerful particulars.

Therefore, the previous analysis of the concept of causal power does not apply to

the powers of ultimate entities. In fact, it follows that the concept of causal power

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

69

developed in CP is not as unified as Harr and Madden sometimes seem to

suggest.

Harr and Maddens account of the concept of causal power is also explicitly

essentialist, although their essentialism is rather sophisticated in the following

respects. Firstly, they do not claim that all entities possess essences but, instead,

restrict their essentialism to the domain of powerful particulars. They also think

that the essences of complex powerful particulars may change, although they

believe that ultimate entities are unchanging powers (ibid. 15057, 161163).

Following John Locke, they move on to distinguish the nominal essences of things

(i.e. observable properties that are normally used in the classification of things)

from their real essences (i.e. usually unobservable intrinsic natures that generate

their manifest properties) and restrict their concept of the essential nature to the real

essences of things (ibid. 1618, 101102). Subsequently, according to their view,

the only changes in the real essence of a powerful particular are those changes in

its essential nature (e.g. ibid. 150). In a similar manner, Harr and Madden

differentiate essential changes from the inessential changes of powerful particulars.

Leaving aside deeply metaphysical questions concerning identity and change,

I think that the concept of essential nature might have some legitimate uses in

certain scientific contexts (e.g. elementary particle physics, chemistry), but it is

inappropriate in many others. For example, biological species do not form such

natural kinds as those that can be separated from each other by referring to the

common essential natures of the individuals belonging to a certain species (see e.g.

Sober 1980). Furthermore, there is controversy surrounding the existence or not

of psychological and social kinds that might be identified by referring to their

essential natures (see e.g. Sayer 1997). Even though these and other examples

suggest that global essentialism is clearly problematic, there might still be some

local candidates (e.g. elementary charges, atoms, and molecules) that possess

something akin to real essences in the sense that Harr and Maddens describe.

Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the question of whether a certain

thing possesses an essential nature or not is an empirical one. It follows from this

that the uses of the concept of causal power developed in CP should be either

restricted to such fields where it can be plausibly applied or, alternatively, that this

concept should be redefined without reference to the essential natures of powerful

particulars. I prefer the latter option as, otherwise, the uses of the concept of

causal power in different sciences would be restricted remarkably. Andrew Sayer

(1997) defends a similar position, which he labels as moderate essentialism, but

I think that moderate anti-essentialism is an equally good name for this view.

HARR AND SECORD ON HUMAN POWERS AND HUMAN NATURES

In ESB, Harr and Secord argue that, within the social sciences, human beings

should be understood as active and knowledgeable agents who are capable of

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

70

Tuukka Kaidesoja

initiating action. ESB also contains a thorough critique of the behaviouristic

experimental social psychology and a sketch of an alternative ethogenic methodology for social psychology. The basic principle of the ethogenic methodology

states that; [f]or scientific purposes, treat people as if they were human beings

(Harr & Secord 1972, 84). In accordance with this principle, Harr and Secords

ethogenic methodology emphasises the relevance of an agents own accounts of

their actions, negotiations with agents, the episodic nature of social action, and

the importance of rules for the explanation of social action. They base this new

methodology on their anthropomorphic model of man, which conceives human

beings as possessors of certain general powers that are exercised in meaningful

and rule-governed social action. These powers include the power to initiate change,

the power to use language, the power to monitor action, the power to monitor

the monitoring of action, and, finally, the power to provide self-commentaries on

actions (see ibid. 84100).

Moving on, in ESB, Harr and Secord (ibid. 82) write that; identification of

powers and natures must form essential parts of the methodology of the social

sciences just as they do in the natural sciences. They also contend that the

concept of power and concepts like it, can provide a system capable of being

used to bring a unity of an acceptable sort into the whole field of disparate kinds

of knowledge of human beings (ibid. 245). These disparate kinds of knowledge

of human beings include the so-called folk psychology embedded in our ordinary

language concepts, psychological explanations of human behaviours, and actions

and neurophysiological knowledge concerning the human nervous system. Harr

and Secord (e.g. ibid. 253) maintain that different kinds of behaviours and actions,

in which human powers are exercised, should be classified by using the concepts

used in everyday language. In accordance with these views, they suggest, quite

optimistically, that the concepts of ordinary language, elaborated by using the

conceptual system of powers, are capable of providing a secure basis for conceptual

integration in the human sciences (e.g. ibid. 240). This position is closely related

to their previously described anthropomorphic model of man.

Harr and Secord (see e.g. ibid. 248251) assert that the logical structure of

the ascription of human powers fits the general logical structure of the ascription

of powers presented above. Familiar distinctions between enabling and stimulus

conditions (or internal and external stimuli), and between intrinsic and extrinsic

conditions, also appear in ESB. These distinctions are, however, elaborated in a

way that, in certain respects, differs from their use in CP and Harrs earlier

works. In addition, subtle but rather underdeveloped classifications of human

powers (e.g. a distinction between general capacities and specific states of

readiness, permanent and transitional powers, powers and liabilities, long- and

short-term powers, generic and specific powers, powers to act and powers to

acquire powers) are presented in ESB. Consequently, it is not always entirely

clear whether the possessors of certain kinds of powers are biological individuals,

persons, social selves, or social episodes. It is also notable that Harr and

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

71

Secord avoid using the concept of causality in their account of the concept of

human power and, remarkably, restrict its legitimate use in their ethogenic

methodology. For this reason, it is not entirely clear whether human powers

should be conceived as genuine causal powers or, rather, as being analogous with

them only in some respects. Nevertheless, I will proceed as if they were genuine

causal powers.

In what follows, I argue that Harr and Secords account of human powers and

human natures contains two intersecting tensions: (1) between an individualistic

and a collectivist ontology, and (2) between an anti-naturalistic Kantian idea of

autonomous person and a naturalistic conception of human beings as biological

individuals. Similar tensions, as I will later argue, are also visible in the critical

realist social ontology. In addition, my critical remarks concerning the analysis of

the concept of causal power in CP are also, in a large part, applicable to the

concept of human power and human nature developed in ESB. For example, the

lack of the notion of emergent power is problematic in ESB because human

beings are obviously such complex organisms, composed of complex parts and

possessing powers ontologically irreducible to their parts. The essentialist analysis

of the concept of causal power presented in CP is also problematic in the context

of the social sciences. Instead of repeating these remarks here, I will focus on the

previously mentioned tensions that can found in the concepts of human power

and human nature used in ESB.

Harr and Secords account of human powers oscillates between an individualist ontology and a collectivist ontology. In some passages in ESB, human powers

are conceived in plainly individualistic terms. Harr and Secord (ibid. 277278)

note, for example, that from a metaphysical point of view: the whole enterprise

of this book can be seen as the attempt to replace a conceptual system, inherited

from the seventeenth century and based upon the substance and quality, with a

system based upon of an individual with powers. Of course, the term individual

refers here not only to individual human beings but also to powerful particulars

studied in the natural sciences. Harr and Secord do not, however, explicitly treat

social groups or collectives as if they were individuals or analogous with them.

They write, for example, that [t]he processes that are productive of social behaviour

occur in individual people, and it is individual people that they [social psychologists]

must study (ibid. 133). In addition, an individualistic interpretation of human

powers is presupposed in Harr and Secords (see e.g. ibid. 89, 246247, 270

271) view that human powers are tied to the currently unknown internal nature

of human beings, which consist of both psychic and physical (or physiological)

aspects. Furthermore, the metaphysical doctrine of dual-aspect materialism that

they espouse seems to require that human powers are tightly connected to the

physiological structures and processes of individual human beings (see ibid, 24).

As far as I can see, this individualistic interpretation of the concept of human

power does not violate Harr and Maddens (1975) account of the concept of

causal power, although it may contain other problems.

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

72

Tuukka Kaidesoja

Nevertheless, there are other places in ESB that differ from the purely individualistic account of human powers. To begin with, Harr and Secord (e.g. ibid.

275271) distinguish permanent human powers, such as the power to speak

English, from transitory human powers such as moods, attitudes and characters,

and maintain that transitory powers are not tied to the permanent features of

human nature but, rather, to the transitory aspects of human nature (ibid.

281). They also suggest that these transitory human powers are highly dependent

on the social episodes (e.g. a dinner party, quarrel, or lecture) in which they occur

(ibid. 153). Secondly, they separate the concept of human nature from the concept

of biological individual and claim that a certain biological individual may possess

many natures, which, they believe, may be understood as her different social

selves (e.g. ibid. 9295, 127, 143145, 276288). Again, these social selves seem

to be highly dependent on different kinds of social episodes. Thirdly, Harr and

Secord maintain that certain kinds of human actions should be explained by using

concepts such as rule, role, and meaning. It seems to me that they, at least

implicitly, conceive these concepts especially the concept of ruleas referring

to certain kinds of collective entities that enable and guide the actions of individuals, although they admit that the effects of these entities are always mediated by

the actions of self-monitoring individuals (see e.g. ibid. 147204). Furthermore,

they write that; [the institutional] environment is operative both in its effects

upon the natures of people, and in providing opportunities and background for the

display of those natures (ibid. 258). It seems to me that it is presupposed in these

views that rules and institutions possess causal powers that are ontologically

irreducible to those of individuals. Now, it may be concluded from the previous

points that Harr and Secord at least implicitly presuppose that some human

powers are properties of collective entities, although they maintain that these

powers manifest themselves only through the actions of individuals. This collectivist

interpretation of human powers is incompatible with the individualistic interpretation of the concept of human power and I will return to this issue in the context

of critical realist social ontology.

Another tension in Harr and Secords analysis of human powers and natures

can be found between their application of the Kantian conception of person and

the concept of biological individual. One of the central motives behind their book

seems to be the rehabilitation of an anti-naturalist Kantian idea, according to

which, human being are autonomous agents that possess power to initiate action

independently of any antecedent causes. This idea was abandoned by behaviourist social psychologists who advocate a mechanistic conception of human beings.

Harr and Secord argue, for example, that human beings should not be conceived as passive organisms who automatically react to environmental stimuli,

but, rather, as persons capable of initiating action, directing their action, monitoring their action, and monitoring their monitoring of this action (ibid. 2943; 84

100). Moreover, they contend, in a Kantian spirit, that these general human

powers are some kind of transcendental presuppositions that are the necessary

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

73

conditions for something to be a language user (ibid. 84) and derive descriptions

of these powers from a priori philosophical analysis of the concept of person (ibid.

3742; 9192). It seems to me that this also explains why a naturalistic perspective on the phylogenetic and ontogenetic development of these human powers

is missing in ESB. Furthermore, in their discussion of the nature of intentional

action, Harr and Secord distinguish the concept of reason from the concept of

cause and are rather critical regarding a causal explanation of intentional action

(ibid. 1112, 159 162). Despite their conceptual distinction between reasons and

causes, they admit that there are intermediate cases of human action, which they

call enigmatic episodes, where both a reason/rule-following explanation and

causal explanation might be applicable (e.g. ibid. 162, 171, 179181). Nevertheless, they seem to be willing to remove reasons for action from the causal order

of nature. This kind of talk, which conceives human beings as autonomous agents,

also includes an irreducible moral component since, in the Western philosophical

tradition, and in our everyday discourse, the concept of autonomous agent is

tied inseparably to the concept of moral responsibility.3 Although this antinaturalist position is, in a certain sense, individualistic, it assumes that some kind

of transcendental powers separate human beings from the causal order of nature.

Therefore, it seems to be incompatible with the previously discussed more naturalistic interpretation of human powers, in which human powers are ontologically

tied to the nature of individual biological organisms.

In his later works on social ontology, Harr (1990; 1993; see also Harr &

Gillett 1994) has gradually abandoned the concepts of human power and human

nature in favour of concepts such as conversation, discourse, grammar, narrative,

and moral order (see also Shotter 1990). He writes, for example, that; there are

only two human realities: physiology and discourse (conversation)the former an

individual phenomenon, the latter collective (Harr 1990, 345) and that primary

human reality is conversation (ibid. 341). Furthermore, he also complains about

the confusion of causal necessity for moral obligation and suggests that the

concept of causality does not have any applications in the social constructionist

ontology and methodology of the social sciences (ibid. 350352; see also Harr

1993). Harr (1990, 352) also contends that in ESB he and Secord were still

thinking in terms of traditional metaphysics, in which the ontology of human

studies is grounded in human beings, whereas now he concedes that this

approach was misplaced. I will come back to Harrs more recent position on

social ontology when I deal with Harr and Varelas critique concerning critical

realist social ontology. Next, I will turn my attention to Bhaskars RTS.

BHASKAR ON CAUSAL POWERS IN A REALIST THEORY OF SCIENCE

Bhaskar adopted the concept of causal power in his RTS from the philosophical

works of his teacher Rom Harr. For this reason, it is not surprising that there are

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

74

Tuukka Kaidesoja

many similarities between Harr and Maddens (1975) analysis of this concept

and Bhaskars own characterisations. Bhaskar (1978) writes, for example, that:

Most things are complex objects in virtue of which they possess an ensemble of tendencies,

liabilities, and powers. (p. 51)

To ascribe a power is to say that thing will do (or suffer) something, under the appropriate

conditions, in virtue of its nature. (p. 175)

The real essences of things are their intrinsic structures, atomic constitutions and so on which

constitute the real basis of their natural tendencies and causal powers. (p. 174)

These statements are almost identical to Harr and Maddens analysis of the

concept of causal power. In RTS, Bhaskar also uses the related concepts of natural

necessity, natural kind, and generative mechanism in a similar way as Harr and

Madden. Furthermore, he presents a sketch of the development of science by

using the concept of causal power in very much the same way as Harr and

Madden (see ibid. 168178). When compared to CP, there are, however, a few

interesting differences in Bhaskars account of this concept in RTS. I focus on

these differences here.

In general, in RTS and his other works, Bhaskar advocates a more openly

ontological (or metaphysical) realism than Harr and Madden in CP and Harr

(see e.g. 1986) in his other works on philosophy of science. Unlike Harr and

Madden, Bhaskar also uses a transcendental method of argumentation in the

justification of his transcendental realist ontological position. He argues in RTS,

for example, that it is a necessary condition of the possibility of scientific experimentation that causal laws/mechanisms, which are ontologically grounded in the

causal powers of things, are categorically distinct from the patterns of events that

they generate (Bhaskar 1978, 3336, 4555). Furthermore, when compared to

Harr and Maddens book-length exposition of the concept of causal power,

Bhaskars account of this concept in RTS is more superficial as it lacks, for example,

clear criteria that would enable powerful particulars to be identified (Varela &

Harr 1996, 318). Bhaskars distinctions between the different kinds of causal

powers are also more modest than those presented in CP. In addition to these

differences concerning their general approach, there are also two specific points

in which Bhaskars account of causal powers differs from Harr and Maddens.

Firstly, as I have previously stated, Bhaskar argues that mechanisms ontologically grounded in the causal powers of things are categorically distinct from the

actual events that they produce. He also states that causal laws conceived as ways

of acting of powerful things must be analysed as tendencies due to the fact that

there are situations in which the exercised causal powers of things fail to generate

manifest effects at the level of actual events (Bhaskar 1978, 14; 50). For this

reason, Bhaskar (ibid. 14) writes that; tendencies may be regarded as powers or

liabilities of a thing which may be exercised without being manifest in any particular

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

75

outcome. Therefore, causal powers are understood in RTS as non-actual and,

consequently, non-empirical features of reality, which, in principle, lie beyond our

unaided perceptual capacities and scientific observations, made by using sense

extending instruments (see e.g. ibid. 4950). It is worth noting that Bhaskar is not

only stating that causal powers exist in the form of the potentialities of things

outside the conditions of their exercise, rather he also suggests that exercised

causal powers are categorically distinct from the actual effects that they produce.

Therefore, according to this view, exercised causal powers also seem to lie beyond

observable phenomena, although their actual effects may be observable in certain

conditions.

I refer to the aforementioned view as a transcendental account of the concept of causal

power because, according to this, (1) the existence of the causal powers of things

belong to the necessary conditions of the possibility of successful scientific

practices and, (2) the causal powers of things exist in a special ontological realm

beyond the realm of the actual events and processes that constitute the possible

objects of our experiences (see also Varela & Harr 1996, 318). It is notable that,

by contrast, Harr and Madden (1975, 4962) argue that, in certain conditions,

it is not just the effects of the exercise of causal powers that are observable, but

also certain causal powers at work can be directly perceived. Therefore, according

to their view, causal powers are not transcendental features of reality by definition,

although they admit that the causal powers of things exists as potentialities outside

the circumstances in which they are exercised, and that, in many cases, the

exercised causal powers that produce observable effects are currently unobservable

features of reality.4

Bhaskars transcendental account of the concept of causal power is problematic, because it locates the causal powers of things in an ontological realm, which,

in principle, lies beyond the realm of actual entities (see also Gibson 1982, 305).

From this perspective, it becomes problematic to answer to the question: how are

causal powers of things related to actual entities (e.g. observable events, processes,

things and states of affairs)? It is not enough to assert that the exercised causal

powers somehow produce the actual objects of observations, because the precise

nature of this relation of production remains inevitably obscure since it is hard to

see how something that is categorically distinct from actual entities could produce

any actual spatio-temporal effects. Consequently, the relationship between the

causal powers of things and actual causation remains obscure in Bhaskars

account (see e.g. Elder-Vass, 331337). This problem seems to be analogous to

the problem of the relationship between things-in-themselves and objects of our

experience (appearances) in the so-called two-worlds interpretation of Kants

transcendental idealism. Nevertheless, it is clear that Bhaskar does not explicitly

advocate this Kantian doctrine because he believes that the causal powers of

things, unlike Kants things-in-themselves, may be possible objects of our knowledge.

Furthermore, at least three problematic methodological implications seem to

follow from Bhaskars transcendental account of the concept of causal power.

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

76

Tuukka Kaidesoja

Firstly, it seems to be possible to attribute indefinitely many hypothetical transcendental causal powers to a certain thing. Secondly, it seems to be possible to invent

indefinitely many hypothesis that refer to different kinds of transcendental causal

powers that allegedly explain any actual phenomenon in which we are interested.

Thirdly, it follows from the previous two methodological implications that it is

difficult to empirically evaluate the competing hypotheses regarding the causal

powers that putatively participate in the production of a certain actual phenomenon

due to the fact that it is always possible to invent indefinitely many hypotheses that

allegedly refer to transcendental causal powers of things that explain the phenomenon in question (see also Kourikoski & Ylikoski 2006). The first two problematic

implications concern the lack of empirical or methodological restrictions in

terms of the possible uses of the concept of transcendental causal power. The

third is a variation of the Duhem-Quine underdetermination (of theories by data)

thesis.

Laboratory experiments in physics and chemistry provide, according to

Bhaskar (see e.g. 1978, 163170, 191194), an efficient way of evaluating hypotheses concerning the causal powers of things because they enable scientists to study

a certain generative mechanism in isolation from interfering influences. This view

is, however, problematic because if we accept the notion that causal powers are,

in principle, non-actual properties of things, then laboratory experiments also

seem to be vulnerable to the previous methodological problems. Moreover,

outside laboratory conditions, the situation seems to be even worse due to the fact

that there seems to be few methodological tools available for testing empirically

explanatory theories that allegedly refer to such transcendental causal powers of

things, those that operate in these open-systemic conditions. Nevertheless, it is

not entirely clear whether the rather sketchy epistemological and methodological

views that Bhaskar presents in RTS are consistent with his transcendental account

of the concept of causal power.

The second feature that differentiates Bhaskars view from Harr and Maddens,

is that he uses a concept of emergent causal power. As I have argued above, the

notion of emergent causal power is needed in order to avoid ontological

reductionism regarding the causal powers of complex things. In this respect,

Bhaskars concept of emergent causal power is promising; although he is by no

means the first one to use this concept since its historical roots go back to at least

the nineteenth century (see e.g. Beckerman et al. 1992). Furthermore, this concept

is left remarkably underanalysed in RTS and Bhaskars (e.g. 1979, 1982, 1986,

1989, 1994) subsequent books do not offer much help in this matter (see also

Elder-Vass 2005; Sawyer 2005, 8082). In RTS, Bhaskar uses this concept (1) to

describe the properties of the whole of a particular complex thing, which is

composed of parts related to each other (or organised) in specific ways; and (2) to

describe relations between levels of reality without specifying clearly how these

two uses are related (see e.g. 1978, 113; see also 1979, 124125; 1982, 277, 281

284). In his later works, this concept is also applied in several other contexts

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

77

without, so far as I can see, providing any clear analysis of it, nor the relations

between its different uses (see e.g. Bhaskar 1994, 6788). Moreover, Bhaskar does

not specify in RTS, nor in his subsequent works, whether all of the emergent

properties of complex things are causal powers or only some subset of them. It

also remains unclear whether non-physical (e.g. mental or social) emergent causal

powers of complex things supervene5 on the physical properties of these things (cf.

Sawyer 2005, 81). I think that Bhaskars transcendental interpretation of the

concept of causal power also vitiates his account of the concept of emergent

power because it becomes rather difficult to characterise the relationships

between the emergent powers of a given complex thing and the causal powers of

its constituent parts if both of these kinds of powers are conceived of as lying, in

principle, beyond our observations.

For these reasons, and following Elder-Vass (2005), I think that further development of the concept of emergent causal power requires that Bhaskars categorical distinction between the causal powers of things and the actual events is

loosened, and that the concept of emergent power is explicitly defined as characterising the parts-whole relation of the composition of complex things. I also

believe that the concept of the ontological level of reality should be explicitly

defined by referring to the emergent causal powers of complex things in order

avoid postulating ontologically mysterious entities.

CONCEPT OF CAUSAL POWER IN A CRITICAL REALIST SOCIAL ONTOLOGY

In his book, The Possibility of Naturalism (PN), Bhaskar develops a realist social

ontology in which he largely employs his version of the transcendental realist

ontology first presented in RTS. The concept of causal power is, therefore, a

central feature of the critical realist social ontology that is largely built on

Bhaskars philosophical ideas. Generally speaking, critical realists maintain that

social life does not form its own reality, totally distinct from the natural world

governed by the causal laws of nature, but, instead, that it forms a part of the total

causal structure of reality. Nevertheless, they commonly admit that there are

certain specific ontological features that differentiate social entities from natural

entities and, consequently, hold that the specific methods of natural sciences are

not directly applicable to the social sciences. According to Bhaskar (e.g. 1979, 48

49), activity-dependence, concept-dependence, and time-space-dependence are

such properties that differentiate social structures from natural structures.

Furthermore, critical realists commonly advocate a relationist conception of

society in which social structures are understood as internal relations between

social positions and positioned-practices (see e.g. Bhaskar 1979, 5154; see also

Archer 1995; Sayer 1992; Lawson 1997). Examples used by critical realists of

internally related positions are, typically, those such as; capitalist and worker, MP

and constituent, student and teacher, husband and wife (Bhaskar 1979, 36). The

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

78

Tuukka Kaidesoja

idea is that a certain social position, which individual agents occupy, is constituted

by its internal relations to other social positions. Critical realists also emphasise

the point that social reality is stratified in the sense that agents (or persons) and

social structures are ontologically distinct entities in virtue of their sui generis emergent causal powers. Despite this ontological distinction, they nevertheless believe

that structures are continuously reproduced and transformed via the intended

and unintended consequences of agents intentional actions. Furthermore, they

hold that structures are ontologically dependent on the activities of agents in the

sense that structures cease to exist when they are no longer reproduced via the

activities of individual agents. Critical realists also admit that social structures

have historically emerged from the social interaction of such agents, which may

have already passed away, and believe that some pre-existing social structures

always enable and constrain current intentional human actions.6 In addition to

these two basic levels of social reality, namely agents and structures, some critical

realists also distinguish several other levels (see e.g. Archer 1988; 1995; 2000).

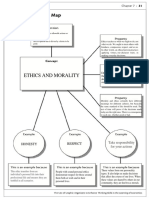

For the sake of clarity, it is useful to differentiate three contexts in which critical

realists have used the concept of causal power in their social ontology: (1) the

context of general mental capacities, (2) the context of reasons, and (3) the context

of social structures. In what follows, I briefly evaluate the uses of this concept by

focusing on one context at the time. I argue that all of these uses are beset by

certain problems. I believe that these problems are at least partly due to critical

realists transcendental interpretation of the concept of causal power and their

ambiguous notion of emergent causal power.

In PN, Bhaskar (1979, 103) writes that; I intend to show that the capacities

that constitute mind [ . . . ] are properly regarded as causal, and that mind is a sui

generis real emergent power of matter, whose autonomy, though real, is nevertheless circumscribed. Following Harr and Secord (1972), Bhaskar (ibid. 44, 104)

maintains that these consciously mediated capacities of people (or agents) include

the power to self-monitor ones own activity, power to monitor the monitoring of

action, and the power to manipulate symbols. He also maintains, much like Harr

and Secord (ibid.), that we can derive descriptions of these powers from a priori

conceptual analysis, and that possession of these powers is constitutive of both

human mind and intentional agency (see Bhaskar 1979, 44, 103106). The most

critical realists follow Bhaskar in believing that the existence of these rather antinaturalistically and individualistically interpreted general mental powers to be one

of the ontological presuppositions of such social studies that take agency seriously.

It is not prima facie implausible to state that the mind is constituted of an

ensemble of emergent causal powers. Nevertheless, this view notably remains

underdeveloped in Bhaskar and other critical realists works. They have not provided sufficient answers to the following questions: what exactly are these general

emergent powers that constitute mind? What is the exact relationship between

mental powers and neurophysiological structures and processes? How does social

context shape the development and the exercise of mental powers? How do

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

79

mental powers develop ontologenetically, and how have they evolved phylogenetically? Unfortunately, Bhaskars (see e.g. 1979, 124125) rather sketchy doctrine

of synchronic emergent powers materialism does not provide the required

answers because it is, as I have previously argued, open to many different

interpretations and conceptually ambiguous. Furthermore, Bhaskars reliance on

an a priori philosophical argumentation, as well as his transcendental account of

the concept of causal power, seem to prevent him for providing satisfactory

answers to these questions. Even though I think that the previous questions are

not only extremely difficult but also largely empirical, in the sense that it is not

possible to answer them solely by using a priori philosophical analysis, I nevertheless

believe that they are relevant in regards to the justification of the application of

the concept of causal power to mind.

Critical realists also defend the view that an agents reasons should be conceived of as causes of her/his intentional action. This is where their views differ

from those of Harr and Secord (1972). Bhaskar (1979, 106, 115123), for example,

argues that reasons can be interpreted as generative mechanisms that produce

behaviour in a way analogous to the ways in which the generative mechanisms

studied in the natural sciences produce observable effects. Although he contends

that reasons are possessed in virtue of the exercise of certain general mental

powers, he nevertheless maintains that reasons are sui generis causes of intentional

action (see e.g. ibid. 106). Bhaskar also states that, agents are defined in terms of

their tendencies and powers, among which in the case of human agents, are their

reasons for acting (ibid. 118, see also 106). As such, he conceives the notion of

intentional causality in terms of a theory of causal powers. Now, it seems to be

legitimate to ask here; what is the intrinsic nature of reasons in virtue of which

they possess causal powers? In PN, Bhaskar (1979, 120123) provides quite a

traditional analysis of the concept of reason by using the concepts of desire and belief,

yet it remains unclear how the nature of desires and beliefs, in virtue of which they

allegedly possess causal powers, should be understood. He also states that, Reasons

. . . are beliefs rooted in the practical interests of life (ibid. 123), but does not

develop this idea very far.

Even though Bhaskar does not directly address the previous question, the only

plausible answer available to him seems to be the one in which reason is understood as a certain kind of mental property that supervenes from the neurophysiological properties of the brain. If this is not the case, it becomes impossible to

explain how reasons could produce material effects, which is, according to Bhaskar

(ibid. 117), a necessary condition for their existence, as well as that of causal efficacy.

Although Bhaskar does not use the term supervenience in PN, he explicitly criticises

all kinds of materialistic views that conceive mental states as material properties

of our neurophysiological systems. He argues, among other things, that this doctrine,

which he refers to with the term central state materialism, is necessarily

individualist and reductionist (ibid. 124137). He also states that, I want to argue

[ . . . ] that people possess properties irreducible to those of matter (ibid. 124).

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

80

Tuukka Kaidesoja

I think, however, that a non-reductionist materialist view, which sees mental

properties as the non-physical properties of the neurophysological systems that

supervene from the physical properties of such systems, is compatible with the

emergent materialist doctrine, according to which, mental properties, understood

as states of neurophysiological systems, possess system-level emergent powers that

are ontologically irreducible to the powers of their components (e.g. neurons and

glias). In following this view, mental states could be conceived as a specific kind

of non-physical, and yet material (in the broadest sense of the term), properties of

the neurophysiological system (see e.g. Searle 1992). I also believe that this view

can be developed in such a way that would be compatible with the view that

posits the physical and social environments, in which human beings live (and have

lived), as shaping (and having shaped) their plastic neurophysiological systems,

both ontogenetically and phylogenetically. In other words, it is possible to conceive human neurophysiological systems as open systems that are in continuous

and complex interaction with their environments. This does not amount, however, to a denial of the role that genetic factors play in the development of the

neurophysiological system, but, rather, it requires a rebuttal of genetic determinism

in regards to the properties of such a system.

To conclude: I hope to have shown that Bhaskars criticism of the doctrine of

central state materialism is misplaced and that some kind of biologically

informed non-reductionist materialist perspective on the mind is more plausible

than that which is advocated by Bhaskar. I concede, however, that the points

made above require further conceptual elaboration, and that their validity

depends, among other things, on the results of neuroscientific research. Nonetheless, Bhaskar and other critical realists views of mental powers often seem to be

much closer to the problematic Cartesian mind-body dualism than they are

prepared to admit.

Finally, and perhaps most controversially, critical realists have applied the concept of causal power to social structures. For critical realists, the problem of the

causal efficacy of social structures seems to be the pressing question: how do the

internal relations between social positions affect the actions of the agents that

occupy these positions? Critical realists, for example, commonly write about the

enabling, constraining, and motivating effects of social structures in relation to the

actions of the agents that occupy the structural positions. Accordingly, Bhaskar

and other critical realists contend that internal relations between social positions

and positioned practices posses some kind of transcendental and emergent causal

powers (e.g. ibid. 5152; 6869; see also Archer 1995, 165194; Lawson 1997,

163170; Sayer 1992, chapter 3). According to this view, society, understood as a

totality of social structures, is some kind of transcendental entity that is, not

given, but presupposed by, experience (Bhaskar 1979, 68). Examples of such

powerful social structures include the structure of a capitalistic economy (Bhaskar

1979, 6567; Sayer 1992), the demographic structure (Archer 1995), and the

structure of an educational system (ibid.). Bhaskar (ibid. 51) also suggests that the

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

81

concept of social position may be further analysed by using concepts such as

place, function, rule, task, duty, and right, but does not present a

precise analysis of the meaning these concepts .

Bhaskar (e.g. ibid. 4344; see also 2001, 30), however, suggests, using the

Aristotelian distinction between efficient and material cause, that social structures

should be understood as material causes of social activity, whereas people are the

only efficient causes of social activity. This statement seems to be incompatible

with the view that social structures possess causal powers since, as I suggested in

the beginning of this article, the concept of causal power should be interpreted as

an elaborated version of the Aristotelian concept of efficient cause (see also Harr

& Madden 1975, 57; Lewis 2000, 257258; cf. Manicas 2006, 72). Although

Bhaskars position is, in this respect, ambiguous, I assume that the differentiating

feature of the critical realist social ontology is that it sees the powers of individual

agents and the powers of social structures as ontologically distinct because I

believe that this is the most common view among critical realists. This statement

is, however, not intended as a denial of the fact that there are some advocates of

this tradition who do not accept this view (e.g. Manicas 2006).

Harr and Charles C. Varela (1996 see also Harr 2001, 2002a; 2002b; Varela

2001, 2002) have criticised critical realists for their application of the concept of

causal power to social structures. They argue that the attribution of causal powers

to social structures violates the general logic of the concept of causal power as it

is presented, for example, in CP because it requires among other things that

causal powers are illegitimately separated from powerful particulars. They also

argue that if the concept of causal power is adequately understood, then it is clear

that social structures are not such things that may possess causal powers. It is

notable that the arguments presented by Harr and Varela presuppose that the

general logic of the concept of causal power has been already presented in an

adequate way in Harrs earlier works. I have earlier challenged this presupposition.

Nonetheless, I think that Harr and Varela are right to criticise the critical

realist view that social structures possess relatively autonomous causal powers in

relation to the agents that occupy the positions in these structures. To be convinced of this, it should be emphasised that it is certainly a minimum requirement

for the legitimate application of any adequate concept of causal power to a certain

entity that this entity be a concrete and organised material system that is capable

of producing observable effect(s) in certain conditions and in a relatively autonomous way. Social structures, conceived as sets of abstract internal relations

between social positions and positioned-practices, do not seem to meet this

requirement. Therefore, Harr and Varela (1996, 314; see also Harr 2001,

2002b; Varela 2001) are right to insist that, in some cases, critical realists commit

to the reification of the abstract macro-social concepts (e.g. working class) in their

application of causal powers to social structures. However, I am not entirely

convinced that it follows from this, as Harr and Varela (1996, 316, 322; see also

Harr 2001, 2000a, 2002b) seem to suggest, that all kinds of social structures are

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

82

Tuukka Kaidesoja

nothing but taxonomic categories, which do not refer to any extra-conversational

entities (see also Manicas 2006, 73). It is also an exaggeration to claim that, in

their social ontology, critical realists have tacitly committed to some kind of

structural determinism that totally undermines human agency (see Harr &

Varela 1996, 316; Harr 2001, 26; 2002b).

In addition, it is important to notice, here, that it does not follow from Harr

and Varelas arguments against critical realist social ontology that Harrs social

constructionist ontology is the only viable social ontology compatible with the causal

powers theory. First of all, it is not clear whether Harrs social constructionism

is in fact compatible with the analysis of the concept of causal power presented

in CP. Harr (see e.g. 1993, 98; see also Harr 2002b; Harr & Gillet 1994), for

example, maintains, in his later social ontology, that people are the only causally

efficacious entities in social reality while simultaneously claiming that people are

conversational constructs. Now, it is not at all clear to me how conversational

constructs could satisfy the minimum requirement for the application of the concept

of causal power. It is surely one thing to say that the conversations, in which biological individuals engage in their lives, in many ways shape and modify their powers,

and another to claim that people are nothing but conversational constructs (see

e.g. Archer 2000; Manicas 2006, 4352). I find the first claim perfectly acceptable

and compatible with causal powers theory and the other problematic.

Moreover, even if we deny that social structures, understood as some kind of

abstract internal relations between social positions and positioned-practices,

possess relatively autonomous powers in relation to the agents that occupy the

structural positions, there may still be some other way to apply the concept of

causal power to concrete social systems. By the term concrete social system, I

refer to the organised groups or collectives of individual agents who communicatively interact with each other in relatively stable ways by using symbols, material

resources, and material artefacts.7 If we think of any given concrete social system

in this way (e.g. factories, families, business firms, hospitals, schools, or political

parties), then it may be said that the system as a whole possesses system-level

emergent causal powers in relation to its environment because it fulfils the minimum

requirement for the legitimate use of the concept of causal power. In other words,

these kinds of concrete social systems can be conceived as organised material

systems, although they are not merely physical systems, because they also possess

non-physical emergent causal powers. The environment of the system may, in

turn, consist of individual agents that do not participate in this system, other

social systems, or ecosystems; although in some cases, it may be difficult to decide

where the boundaries of the system lie. Furthermore, these kinds of concrete

social systems might be modelled by using the theory of complex dynamic systems

that radically differ from the traditional functionalism (e.g. Talcott Parsons) in

sociology (see e.g. Sawyer 2005).

It does not follow from the position outlined above that concrete social systems

possess autonomous causal powers in relation to the agents that form their

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

Exploring the Concept of Causal Power in a Critical Realist Tradition

83

components because the emergent causal powers of the previously characterised

social systems are always ontologically and causally dependent on the causal

powers of the acting agents.8 This is not, however, meant to deny the notion that

these kinds of social systems may have been historically formed through the

activities of different agents to those who currently act as their constituent components: nor does not follow from this that the system-level emergent powers of

the social systems can be ontologically reduced to the powers of individual

agents, because these system-level powers are not only ontologically dependent

on the non-relational powers of the agents but also on the relatively stable

dynamic relations between communicatively interacting agents (and the

relations between them and material resources and artefacts). Furthermore, it is

possible to say that the relational structure of the social system (i.e. the set of

relations between its components) also enables, constrains, and motivates the

actions of the agents. In this sense the positions that agents occupy in this kind

of social systems remain important, although it is not possible to ontologically

separate them from the ongoing interaction between agents. Moreover the

relation between the structure and agents in such systems cannot be, due to the

aforementioned reasons, adequately analysed by using the concept of causal

power. Nevertheless, enabling, constraining, and motivating structural relations

may still be interpreted as causal by using some other analysis of the concept of

cause than the causal powers theory. I shall leave it open here as to whether

the previous analysis can be extended to also cover macro-systems such as

welfare states, capitalist economies, and educational systems. Indeed, I also admit

that the concepts of concrete social system, communicative interaction, and

emergent causal power require further analysis than that which must be omitted

here.

The previously stated argument demands that we give up the presupposition

that there only exists a single adequate ontological analysis of the concept of

causality. Although this move makes things conceptually messier, I nevertheless

believe that it leads to a more fruitful interaction between philosophical

analysis and empirical research. Therefore, instead of searching for a single

ontological analysis of the concept of causality, it seem to be more fruitful to

try to specify different kinds of causal relations that are referred to by different kinds of causal concepts applied in different contexts (see Hitchcock

2003). Some critical realists have already proceeded in this direction by

presenting tentative analyses of structural social causation that employ a different

kind of analysis of the concept of cause to that of the causal powers theory (see

Groff 2004; Lewis 2000; see also Patomki 1991). Bhaskar (see e.g. 1986, 132;

1994, 82) has also recently abandoned the presupposition that the causal powers theory provides an adequate analysis of all kinds of causal relations, although

his discussion of the causal powers of social structures is still quite problematic. However, any evaluation of these suggestions forms the topic of another

article.

2007 The Author

Journal compilation The Executive Management Committee/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2007

84

Tuukka Kaidesoja

CONCLUSION

Finally, I want to list briefly the major points that I presented in the previous