Professional Documents

Culture Documents

December 19, 1968

Uploaded by

TheNationMagazineCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

December 19, 1968

Uploaded by

TheNationMagazineCopyright:

Available Formats

128

The Nation

ping off so successfulacareer.Andthat,saythe

boys,

is Frank Hagues game.

These are a few of the chief reasons why independent

Democrats and Smith Republicans in New Jersey are

so

keenly disappointed in Governor Smith. It would have been

bad enough to retain Hague as vice-chairman of the Democratic National Committee. But for

A1 to place a fond arm

around his shoulders and murmur, Hello, Francesco, and,

quite needlessly, to make him an Eastern campaign manager-such

thingsarebitterplllsforthinkingmenand

women.

Can A1 Smith carry New Jersey?

Well, in order to do

so, it will be necessary for hlm to

overcome a normal Re-

[Vol. 127, No. 3292

publican plurality of morethan

300,000. PerhapsBoss

Hague will be able to secure a sufficiently large foreign vote;

perhaps he will find it posslble t o swing an unheard-of number of Smith ballots in Hudson County, where I t is said they

dont count the votes but welgh them. Even then, it

1s hard

to see how Smlthcanwinwithoutmakinggreatinroads

upon the Republican strength and without keeping in line

the independent Democrats, many of whom are thoroughly

disgusted with the Hague regime.

To sum it up, Hague will getmanyJerseyvotesfor

the happy warrior. But he will be responsible for the loss

of many others. And the

ones he loses will be those of progressives who love Smith but hate his company.

Norman T h o m a s

By McALISTER COLEMAN

LANKYsix-feet-two of Ohio-bornboneand muscle

unlimbers itself above the speakers platform at the

corner of Avenue B andHoustonStreet,

on New

Yorks East Side.Flare-lightsthrowthelongshadow

of

NormanThomasacrosstheheads

of hisaudlence,squat

little tailors, for the most part, with here and there smudged

mechanics,truck-drivers,andasprinkling

of womenand

children.

The speaker holds up

a huge enlargement of a photograph of a working-class apartment erected by the Socialists

of Viennaandthenproceedstowonder

loudly and vehementlyhow

it comes thatinacomparativelypovertystrickencitylikeViennafolkspayaroundtwodollars

a

room a month for such splendid quarters, whereas in prosperous New York a worker is hard put to it to find decent

housingatfifteendollars.

Hls audiencebeginstowonder

with him. And then Thomas goes

on to talk of things as

they are and things as they might

be ; simple things llke gas

bills and rents and pay envelopes and the youngstersschooling and the prices the women pay in the stores round about

Avenue B.

One night last year toward the end of a hot campaign

in the Eighth Aldermanic Distrlct

a truck loaded with a

Tammanybandand

a collection of childrenarmedwith

rattlers and other noise-making horrors drove through the

crowd in front of the platform where Thomas was speaking.

The chieftain in charge of the invasion raised a pudgy hand

as a signal to his youthful braves to cutloose and drown out

Thomas.Tohisconsternation,thekids,afterone

look a t

the

speaker,

piped

with

shrill

gusto,

Yeaa!

Norman

Thomas!Thatsafamlllarenoughwar-cryontheEast

Sidewheneverhegoescampaigning.Thechildren,asyet

unterrlfied by Tammanys elaborate and subtle machmery of

fear,suspicion,andgreed,have

no hesitancyinvoicing

their love forNormanThomas.Battalionstrudgetrustingly after him as he goes from

one meeting-place to another, hang on the running-board of his campaign car, and

besiege his headquarters the minute

school is out. And a t

least three or fourtimeswhenThomaswasrunningfor

alderman, mothers appeared with amazingly

vocal infants

whose last names ended in ski or baum but whose first

two names were Norman Thomas.

Sometimes a former classmate of Thomass at Princeton

P respectable hangover from the

Brick Church

days, passing by a street meeting at which Thomas is wondering aloud, stops to do some wondering of his own. How

does it happen that a man of suchobviousability,magnetism,andfieryforcecanstooptoconquertheimaginations and hearts of the citys most submerged-the workers

on the East Side, in the Bronx, and in Brownsville?

If Thomas is interested in the labor movement, all well

and good. Ever so manyintellectualsaretakingupthe

movement, writing pieces about it for magazines andnewspapers, evincing an intelligently alert awareness

of Its existence. But here is Thomas running his

good head off a t

the beck and call of every little union organlzer, every

Socialistwho is gettingup a meetinginsomeremotehall,

every rank-and-filer who has a crowd to reach and a cause

to preach. In last autumnscampalgnThomasmademore

thansixtyspeechesintwomonths,most

of themout-ofdoors, andhewroteenoughwordsto

fill a double-decker

novel-all because he had been nominated for alderman by

a small local of the Socialist Party in

a strong Tammany

district.Whenthevoteswerecounted,anignorantTammanyoptometrist,whoseboastwas

I never go outdoors

during a campaign, was sent back to the aldermanic chamber with a blg majority. And

now Thomas is running f o r

President of theUnitedStates,astheleader

of aparty

whosedeathhas

been officially announcedtimeandagain

these past few years by conservatives and liberals and

extreme radicals allke.

No one need feel sorry for Norman Thomas. There is

littlegloryinwhathe

1s doing.Longnightsinstuffy

sleepers, long days filled with speech-making in labor halls,

at farmers picnics, at Socialist rallies; party conferences;

newspaper Interviews ; pamphlet-writing ; handshaking (at

which, by the way, in spite of long practice Thomas is still

singularly inept)-this

is not most peoples idea of a good

time.ButThomas

is having a magnificenttime.Heis

doing what he wants t o do and doing it well.

It is intheThomas

blood fromthedayswhenthe

Welsh preacher-menThomasesexpoundedtheirvlgorous

doctrinesinthe

old country-thisbusiness

of articulating ideas and ideals. The first of the Thomases t o arrive in

thiscountrycamefromWalesin

1824. HewasThomas

Thomas, a parson with a hill hunger on him which took him

to the mountains of Pennsylvania,where he preachedthe

forbidding doctrines of Calvin with a certain mellow touch

8,19281

The Nation

thatmadehimthemost

beloved man of allthecountry

round. He had found time to work his way through Lafayette College. His son,WellingEvanThomas,

followed i n

hls footsteps and found himself,

of all places, in charge of

thePresbyterianChurchinthelateMr.Hardings

home

town of Marion, Ohio, where Norman was born on November 20, 1884.

The two-story brick parsonage was on Prospect Street,

a home sheltered by huge old maples, with a grape arbor in

the rear, and woods and pasture-land right outside the door.

Even when they moved further into town, and added a

cow

and a bathtub to the establishment, life

a t t h e Thomases

was still largely rural. Norman, the eldest

of six children,

soon learned what hard work meant. A ministerial income

of $1,200 a year for the clothing and feeding

of four boys

andtwogirls,especiallysuchupshootingchildren

as the

Thomases,

was

in

sad

need of supplement.

Everybody

worked in that family, and mingled

a keen respect for the

fatherwithadeep

love forthemother,whobeforeher

marriage was Emma Matoon, adescendant of the French

Huguenots who came to this country in

1650. Her father

was a missionary to Siam and later became American

consul. On hisreturntothiscountry,immediatelyafterthe

Civil War, he started one of t h e first schools for Negroes,

nearCharlotte,NorthCarolina.Starting

schools for Negroes in the South in the turbulent days

of reconstruction

was no light undertaking.

Normanwasobviouslypredestined

for theministry.

He took the Marion HighSchool in his long stride, being one

of the youngest ever to be graduated from that institution,

And then, when the family

moved to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, he entered Bucknell. He was a long, gangling freshman, sticking out of his clothes, and outof his class as well,

for he had read greedily all sorts and varieties

of books back

in the Marion parsonage and easily led his fellows in classroomwork.Bucknellinthosedayswasaboutasrigidly

orthodox a place as one could find, but already the youngster

was beginning to doubt and question the validity of creeds

and dogmas. An unexpectedly

beneficent relative gave him

the chance to enter Princeton.

He left the small Pennsylvania

college in a mood approachingexaltation.Princeton,tohim,hadbeena

place

todreamabout.

I was so afraid I would flunkout,he

says, that worked like a trooper, tutoring at nights, working in a chairfactoryinsummer,andsellingaluminumware. So he stuck in the

first group of his class for the

next three years, and he was valedictorian

of t h a t class of

1905, and one of the most popular men in

college. He was

on the debating team, took all the courses in economics and

politics which Princeton offered, and was moved, as were so

many of the young men of those days, by the Princetonian

Walter Wyckoffs pioneer labor book, The Workers, and

by the great strike

of the anthracite miners led by John

Mitchell. He was caught in the Thomas tradition, and he

made the best compromise with it that he could by taking a

job in the Spring Street Settlement, in New

Yorks slums.

A trip around the world with the director of the settlement laid the foundations for his international outlook, but

it was the World War which finally took him clear out of

church circles into the heartof the labor and Socialistmovement. He was in a church in East Harlem, working among

theforeign-born

of

tenementdistrict,whenthe

war

broughtitschallengetohimasitdidtoeveryChristian

minister. He answered that challenge by flatly refusing to

129

haveanythingto do with the bloody mess. instantlypatrioticpressureswerebroughttobear

on himfromall

sides.

Contributions

to

his

social

work

stopped.

There

wereattempts,mainlyfutile,

at social ostracism. Then

Morris Hlllqult started his crusading campaign for mayor

of New York City, and Thomas, to the utter consternatior.

of all his respectable flag-wavmg assoclates, stood up with

Hillquit in that historic struggle. At the

close of the campaignThomasfound

himself a full-fledgedcard-carrying,

dues-paying member of the Socialist Party, with no church

and only theslendereditorialsalaryfromhispaper,the

World Tomorrow, for the support of a large and husky family. His brother Evan was lugged

off to Jail as a conscientious objector. Snoopers and spies,official and self-appointed,

dogged Norman night and day. Postmaster General Burleson paid him the compliment of saying that Thomas was a

moredangerousmanthan

Debs. Hewas dangerous-for

those who were attempting to make

a clean sweep of civil

liberties; who used the war to exploit labor; dangerous for

the peace of mind of every militarist mmister.

With Roger Baldwin and HollingsworthWood he helped

form the American Civil LibertiesBureau.What

a hated

institution that was ! After the headquarters of the bureau

had been raided, and the magnificently defiant Baldwin had

beensenttojail,much

of thepioneeringworkfellon

Thomass shoulders. And when he was not busy with edltorialandcivil-libertiesaffairs,hewasgoingamongthe

colleges, speaking for the Intercollegiate Socialist Society,

the predecessor of the League for IndustrialDemocracy.

To these two organizatlons, the

one with its program

of freedom of speech, press, and assemblage, and the other

with its goal of production for use rather than profit, and

tothepoliticalexpression

of theseidealsthroughthe

medium of the Socialist Party, Thomas has devoted his surprisingly varied and rich talents.

I havesaidthatThomassempiricalphilosophyhas

unityandconsistency,andthisdespitethefactthathis

usual activities in the course of a day cover what seem to

be a bewildering range of subjects. When the Chinese Nationalists cable for funds, Thomas is on the Committee for

JusticetoChina.WhenthePullmanportersorganize

a

pioneerNegroindustrialunion,Thomasis

called onfor

counsel. When the textile strikers in Passaic are prohibited

from meeting, Thomas is the man who goes over to New

Jersey and speaks under the menace of high-powered rifles

in the hands of the operators gunmen, and goes to jail with

hishead up, so that from then on the strikers may meet

unmolested.Whensomeadequatereplytothepropaganda

of the power lobbybecomes apublicnecessity,Thomasis

the driving spirit of the Committee on Coal and Giant Power

which makes that ringing answer.

Always in the back of Thomassmindisthefundamental necessity for the organization in this country

of a

politicalpartyrepresentingthehopesandaspirations

of

those who produce the countrys wealth by work of hand or

brain. He was one of those who were instrumental in swinging his partys forces into the La Follette campaign, despite

the opposition of manypartySocialists.

I haveheard

Thomas speak under all sorts

of circumstances, and to all

sorts of people, b u t I cannot remember his ever having used

thecredalMarxiandialecticproletariat,bourgeoisie,

the economic interpretation of history-these

are not in

hisvocabularywhenhegoesouttotalktoworkersand

farmers, college students, and professional men

women.

130

The N2tion

Stillheremainsaninternationalist,passionately

following the poignant dreamof bread, peace, and freedom for

people. Whether his speech or pamphlet or statement to

thepressbeginswith

a discussion of theintricacies of

municipal government, to which he brings expert knowledge,

or a headlong attack upon the corruption of both old parties,

or the deepdamnation of imperialism,hegenerally

concludes with a compelling plea for a peaceful world.

When Thomas told the convention which nominated him

in New York that he did not expect to be

elected President

this year, many veteran hands were raised In horror. That

[Vol. 127, No. 3292

was not the sort of thing that a candidate says to his constituents. A sense

of proportion, a richly mellowed understanding of reality, is not found in the arsenalsof most campaigners. It is to the credit of the old-timers in the movement that, knowing very

well NormanThomassfrequent

departures from the faithof the fathers, they chose him for

their leader, and are givmg liberally to make his campaign

a success. And a success it will be, if there is found in this

country by next November a collective intelligence powerful

enough to present to the united front of the two old parties

an opposition worthy of the name.

The Truth About Tsinanfu

By H. J. TIMPERLEY

June 16

APANS statement to the League of Natlons concerningtheTsinanfuaffair,

we aretoldinGeneva

dispatchespublishedhere,hascreated

a favorableimpression. This may

well be so, for the Chinese side of the

argumentwasbadlybungled.

It is improbable,however,

that this impression would be long sustained if the League

whole circumtook a notion to investigate thoroughly the

stances surrounding the case.

One aspect which such an inquiry

could hardly fail to

reveal wouldbe theprovocativeattitude

of theJapanese

military all throughtheaffalr.Neutraleye-witnesses,in

which category I take the liberty of including myself, agree

that the Nationalist occupation of Tsinanfu was as peaceful as could be wished for. The leading Nationalist

columns

whichenteredthecity

on themorning of May 1 halted

quietlya block away from the Japanese barriers and displayed very little excitement about it. Senseless truculence,

on the other hand, was shown from the beginnmg by the

Japanesesoldiery.Notcontentmerelytoremainquietly

watchfulbehindtheirsandbags,asAmericanorBritish

troops would have done, they often were to be seen standIng on top of thebarricadeswiththeirbayonetsthrust

almost under the noses of the Nationalist troops that went

marching by. Here we are, come along and hit us, they

almostsaid.Exceptforaperceptiblelift

of theeyebrow,

the Southerners made no response to these demonstrations.

It became increasmgly evident during the first two days

of theNationalistoccupation,however,thatahighly

explosive situationgraduallywasworkingup.Foreignas

well as Chinese civilians were handled on occasion wlth unnecessary roughness by the Japanese sentries

on post. One

I waspersonally involved occurred

suchepisodeinwhich

wlthln an hour or so of the Southerners entry. I had gone

across to the Tientsm-Pukow station just in time to see the

last of theWhiteRussianarmoredcarsguardingthe

Northern retreat pull out

slowly as the Nationalist troops

appearedalongtherallwayembankment.Chattingwitha

group of the newcomers, I found them peaceably disposed

andfriendly.SteinsHotel,where

I wasstaying,hada

Japanese barricade around it. The sentries stationed there

had let me go across to the station and return through the

I returnedfrom

barricadewithoutquestion,butwhen

second sortie,tothetelegraph

office, a Japanesesoldier

clubbed me viciously in the small of the back with the buttend of his rlfle. It wasamostuncalled-forexhlbitlon

of

Ill-tempered violence, and within a very short space of time

was telling the Japanese Consul so. Subsequent negotlations,duringwhichitwasexplained

that mynameinadvertentlyhad been omitted from the list

of fore~gners to

whom permits to pass through the barriers had

been supplied, ended in a verbal apology being offered by a Japanese

staff officer to the British Consul, as well as to myself. In

fairness it ought to be mentioned that the Japanese Consul

was visibly distressed by the incident and spared

no effort

to see that proper amends were made.

I was around the city

good deal on the mornmg of

May 2 and took special interest in the actrvities of the Natlonalistpropagandists.Littlesquads

of themweregoing

quletly about the business of plastering the town with posters setting forth the aims of the Nationalist campaign and

denouncingtheNorthernmilitarists.

One poster showed

Chang Tro-lin whispering sweet nothings into the ear

of a

coyly smiling Japanese geisha, while another depicted him

and Japan tugging at opposite ends of a chain and strangling China between them. How the walls

of Peking would

totter when the Natlonalists got there was demonstrated by

anothersheet.Pictures

of SunYat-senandChiangKaishekweredisplayedsidebysideandpropaganda

leaflets

were broadcast in the streets. Interested groups

of Chinese

coolies gazed at the posters or listened open-mouthed to the

by the

streetlecturers.Some

of thelatterwerearrested

Japanesedurmgthemorning.

Nobody seemedto

know

in cuswhy. I sawthembeingmarchedalongthestreet

tody.Theywentalongquitegood-humoredlywiththem

unsmilmg guards and

even salutedaJapanese

officer who

canteredup

on a horse. Some werereleasedafterward,

but the maJority were detained and no information could be

a good deal of resentobtainedaboutthem.Thisaroused

ment among the Nationalists, though, so Chiang Kai-sheks

staff officers told me,news of it mas suppressedinorder

nottoexcitethetroops.Chlangsstaff

alsotold me t h a t

on this day Nationahst officer, described by them as being

the Chief of Transportation, was shot

by Japanese troops

infront of the Tsinan Pao newspaper office. Theywere

notabletotellmeanything

of thecircumstancesand

I

could get no confirmation of it from any other source.

By the night of May 2 the Japanese apparently felt the

situation tranquil enough to Justify the withdrawal

of the

My

barrlcades,andthesewereremovedtowardmidnight.

understandmgas a result of inquiriesmade at thetime

was that thls step was taken purely on the initiative of the

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Army Holiday Leave MemoDocument5 pagesArmy Holiday Leave MemoTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Bloomberg 2020 Campaign Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)Document11 pagesBloomberg 2020 Campaign Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)TheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Nasoya FoodsDocument2 pagesNasoya Foodsanamta100% (1)

- Reflection Paper 1Document5 pagesReflection Paper 1Juliean Torres AkiatanNo ratings yet

- Nguyen Dang Bao Tran - s3801633 - Assignment 1 Business Report - BAFI3184 Business FinanceDocument14 pagesNguyen Dang Bao Tran - s3801633 - Assignment 1 Business Report - BAFI3184 Business FinanceNgọc MaiNo ratings yet

- Arlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsDocument1 pageArlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Re Unauthorized Disclosure Crime ReportsDocument5 pagesKen Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Re Unauthorized Disclosure Crime ReportsTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Against 8 Federal AgenciesDocument13 pagesKen Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Against 8 Federal AgenciesTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- FOIA LawsuitDocument13 pagesFOIA LawsuitTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Arlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsDocument1 pageArlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Read House Trial BriefDocument80 pagesRead House Trial Briefkballuck1100% (1)

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA LawsuitDocument121 pagesKen Klippenstein FOIA LawsuitTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Boogaloo Adherents Likely Increasing Anti-Government Violent Rhetoric and ActivitiesDocument10 pagesBoogaloo Adherents Likely Increasing Anti-Government Violent Rhetoric and ActivitiesTheNationMagazine100% (7)

- Physicalthreatsabcd123 SafeDocument5 pagesPhysicalthreatsabcd123 SafeTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Open Records Lawsuit Re Chicago Police DepartmentDocument43 pagesOpen Records Lawsuit Re Chicago Police DepartmentTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Letter From Sen. Wyden To DHS On Portland SurveillanceDocument2 pagesLetter From Sen. Wyden To DHS On Portland SurveillanceTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- ICE FOIA DocumentsDocument69 pagesICE FOIA DocumentsTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Violent Opportunists Using A Stolen Minneapolis Police Department Portal Radio To Influence Minneapolis Law Enforcement Operations in Late May 2020Document3 pagesViolent Opportunists Using A Stolen Minneapolis Police Department Portal Radio To Influence Minneapolis Law Enforcement Operations in Late May 2020TheNationMagazine100% (1)

- DHS ViolentOpportunistsCivilDisturbancesDocument4 pagesDHS ViolentOpportunistsCivilDisturbancesKristina WongNo ratings yet

- FBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFDocument5 pagesFBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFWilliam LeducNo ratings yet

- Civil Unrest in Response To Death of George Floyd Threatens Law Enforcement Supporters' Safety, As of May 2020Document4 pagesCivil Unrest in Response To Death of George Floyd Threatens Law Enforcement Supporters' Safety, As of May 2020TheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Social Media Very Likely Used To Spread Tradecraft Techniques To Impede Law Enforcement Detection Efforts of Illegal Activity in Central Florida Civil Rights Protests, As of 4 June 2020Document5 pagesSocial Media Very Likely Used To Spread Tradecraft Techniques To Impede Law Enforcement Detection Efforts of Illegal Activity in Central Florida Civil Rights Protests, As of 4 June 2020TheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- The Syrian Conflict and Its Nexus To U.S.-based Antifascist MovementsDocument6 pagesThe Syrian Conflict and Its Nexus To U.S.-based Antifascist MovementsTheNationMagazine100% (4)

- Opportunistic Domestic Extremists Threaten To Use Ongoing Protests To Further Ideological and Political GoalsDocument4 pagesOpportunistic Domestic Extremists Threaten To Use Ongoing Protests To Further Ideological and Political GoalsTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Some Violent Opportunists Probably Engaging in Organized ActivitiesDocument5 pagesSome Violent Opportunists Probably Engaging in Organized ActivitiesTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Sun Tzu PosterDocument1 pageSun Tzu PosterTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Violent Opportunists Continue To Engage in Organized ActivitiesDocument4 pagesViolent Opportunists Continue To Engage in Organized ActivitiesTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- CBP Memo Re We Build The WallDocument6 pagesCBP Memo Re We Build The WallTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Law Enforcement Identification Transparency Act of 2020Document5 pagesLaw Enforcement Identification Transparency Act of 2020TheNationMagazine50% (2)

- CBP Pandemic ResponseDocument247 pagesCBP Pandemic ResponseTheNationMagazine100% (9)

- Responses To QuestionsDocument19 pagesResponses To QuestionsTheNationMagazine100% (2)

- DHS Portland GuidanceDocument3 pagesDHS Portland GuidanceTheNationMagazine100% (2)

- AFRICOM Meeting ReadoutDocument3 pagesAFRICOM Meeting ReadoutTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Expected MCQs CompressedDocument31 pagesExpected MCQs CompressedAdithya kesavNo ratings yet

- Study of Means End Value Chain ModelDocument19 pagesStudy of Means End Value Chain ModelPiyush Padgil100% (1)

- Volvo B13R Data SheetDocument2 pagesVolvo B13R Data Sheetarunkdevassy100% (1)

- Double Inlet Airfoil Fans - AtzafDocument52 pagesDouble Inlet Airfoil Fans - AtzafDaniel AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Kit 2: Essential COVID-19 WASH in SchoolDocument8 pagesKit 2: Essential COVID-19 WASH in SchooltamanimoNo ratings yet

- PRELEC 1 Updates in Managerial Accounting Notes PDFDocument6 pagesPRELEC 1 Updates in Managerial Accounting Notes PDFRaichele FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Rundown Rakernas & Seminar PABMI - Final-1Document6 pagesRundown Rakernas & Seminar PABMI - Final-1MarthinNo ratings yet

- Dunham Bush Midwall Split R410a InverterDocument2 pagesDunham Bush Midwall Split R410a InverterAgnaldo Caetano100% (1)

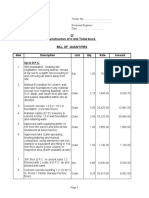

- Type BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Document6 pagesType BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Yashika Bhathiya JayasingheNo ratings yet

- 16 Easy Steps To Start PCB Circuit DesignDocument10 pages16 Easy Steps To Start PCB Circuit DesignjackNo ratings yet

- Consultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportDocument6 pagesConsultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportNitish RamdaworNo ratings yet

- Coursework For ResumeDocument7 pagesCoursework For Resumeafjwdxrctmsmwf100% (2)

- Sikkim Manipal MBA 1 SEM MB0038-Management Process and Organization Behavior-MQPDocument15 pagesSikkim Manipal MBA 1 SEM MB0038-Management Process and Organization Behavior-MQPHemant MeenaNo ratings yet

- Reading TPO 49 Used June 17 To 20 10am To 12pm Small Group Tutoring1Document27 pagesReading TPO 49 Used June 17 To 20 10am To 12pm Small Group Tutoring1shehla khanNo ratings yet

- Is 778 - Copper Alloy ValvesDocument27 pagesIs 778 - Copper Alloy ValvesMuthu KumaranNo ratings yet

- Idmt Curve CalulationDocument5 pagesIdmt Curve CalulationHimesh NairNo ratings yet

- Dreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsDocument22 pagesDreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsManoel ValentimNo ratings yet

- DTMF Controlled Robot Without Microcontroller (Aranju Peter)Document10 pagesDTMF Controlled Robot Without Microcontroller (Aranju Peter)adebayo gabrielNo ratings yet

- La Bugal-b'Laan Tribal Association Et - Al Vs Ramos Et - AlDocument6 pagesLa Bugal-b'Laan Tribal Association Et - Al Vs Ramos Et - AlMarlouis U. PlanasNo ratings yet

- Woodward GCP30 Configuration 37278 - BDocument174 pagesWoodward GCP30 Configuration 37278 - BDave Potter100% (1)

- Gathering Package 2023Document2 pagesGathering Package 2023Sudiantara abasNo ratings yet

- Marshall Baillieu: Ian Marshall Baillieu (Born 6 June 1937) Is A Former AustralianDocument3 pagesMarshall Baillieu: Ian Marshall Baillieu (Born 6 June 1937) Is A Former AustralianValenVidelaNo ratings yet

- To Syed Ubed - For UpdationDocument1 pageTo Syed Ubed - For Updationshrikanth5singhNo ratings yet

- TENDER DOSSIER - Odweyne Water PanDocument15 pagesTENDER DOSSIER - Odweyne Water PanMukhtar Case2022No ratings yet

- Musings On A Rodin CoilDocument2 pagesMusings On A Rodin CoilWFSCAO100% (1)

- For Email Daily Thermetrics TSTC Product BrochureDocument5 pagesFor Email Daily Thermetrics TSTC Product BrochureIlkuNo ratings yet

- Saic-M-2012 Rev 7 StructureDocument6 pagesSaic-M-2012 Rev 7 StructuremohamedqcNo ratings yet