Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Comparison of Intraincisional Injection Tramadol, Pethidine and Bupivacaine On Postcesarean Section Pain Relief Under Spinal Anesthesia

Uploaded by

Syukron AmrullahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Comparison of Intraincisional Injection Tramadol, Pethidine and Bupivacaine On Postcesarean Section Pain Relief Under Spinal Anesthesia

Uploaded by

Syukron AmrullahCopyright:

Available Formats

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.

6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Original Article

The comparison of intraincisional injection tramadol,

pethidine and bupivacaine on postcesarean section pain

relief under spinal anesthesia

Mitra Jabalameli, Mohammadreza Safavi, Azim Honarmand, Hamid Saryazdi, Darioush Moradi,

Parviz Kashefi

Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Anesthesiology and Critical Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical

Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Abstract

Background: Bupivacaine, tramadol, and pethidine has local anesthetic effect. The aim of this study was to

compare effect of subcutaneous (SC) infiltration of tramadol, pethidine, and bupivacaine on postoperative

pain relief after cesarean delivery.

Materials and Methods: 120 patient, scheduled for elective cesarean section under spinal anesthesia, were

randomly allocated to 1 of the 4 groups according to the drugs used for postoperative analgesia: Group P

(Pethidine) 50 mg ,Group T (Tramadol) 40 mg, Group B (Bupivacaine 0.25%) 0.7 mg/kg, and Group C (control)

20CC normal saline injection in incision site of surgery. Pain intensity (VAS = visual analogous scale) at rest

and on coughing and opioid consumption were assessed on arrival in the recovery room, and then 15, 30,

60 minutes and 2, 6, 12, 24 hours after that.

Results: VAS scores were significantly lower in groups T and P compared with groups B and C except for 24

hours (VAS rest) and 6 hours (VAS on coughing) postoperatively (P < 0.05). The number of patients requiring

morphine were significantly different between the groups (105 doses vs. 87, 56, 46, doses for group C, B,

T and P, respectively, P < 0.05) in all the times, except for 2 and 6 hours postoperatively.

Conclusions: The administration of subcutaneous pethidine or tramadol after cesarean section improves

analgesia and has a significant morphine-sparing effect compared with bupivacaine and control groups.

Key Words: bupivacaine, pethidine, post-cesarean section pain, spinal anesthesia, tramadol

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Mohammadreza Safavi, Associate Professor of Anesthesia and Critical Care, Anesthesiology and Critical Care Research Center, Isfahan University of

Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. E-mail: safavi@med.mui.ac.ir

Received: 17.02.2012, Accepted: 18.05.2012

INTRODUCTION

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website:

www.advbiores.net

DOI:

10.4103/2277-9175.100165

Females undergoing cesarean section often wish

to be awake postoperatively and to avoid excessive

medications affecting interactions with their newborn

infant and visitors.[1] Local anesthetics are widely used

to provide postoperative pain relief, but analgesia is

rarely maintained for more than 4-8 hours with largest

acting local anesthetics (bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and

Copyright: 2012 Jabalameli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

How to cite this article: Jabalameli M, Safavi M, Honarmand A, Saryazdi H, Moradi D, Kashefi P. The comparison of intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine

and bupivacaine on postcesarean section pain relief under spinal anesthesia. Adv Biomed Res 2012;1:53.

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3 1

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Jabalmeli, et al.: Intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine, bupivacaine analgesia

levobbupivacaine) after administration incisional.[2]

The systemic administration of high doses of opiates

has been associated with side effects ranging

from pruritus, nausea, and vomiting, to sedation

and respiratory depression. [3-5] Subcutaneous

administration of opiates is a method of postoperative

pain control after cesarean section.[1] Opioids may

produce analgesia through peripheral mechanisms.[6]

Immune cells infiltrating the inflammation site may

release endogenous opioid-like substances, which act

on the opioid receptors located on the primary sensory

neuron.[6] However, other studies do not support this

conclusion.[7,8] Potential advantages of subcutaneous

route include no first pass drug metabolism by the

liver, improved patient compliance, convenience, and

comfort; and consistent analgesia.[9] Local anesthetic

effects of opioids have been demonstrated in several

studies; tramadol is an analgesic with different

spectrums of activity.[10] It cause the activation of both

opioid and non-opioid (descending monoaminergic)

systems, which are mainly involved in the inhibition

of pain. Meperidine has been classified as an agonist

of both - and K-receptors. [5] The postoperative

analgesic effects of subcutaneous wound infiltration

with tramadol have not been extensively studied and

compared with the same routs of local anesthetics or

opioids. To the best of our knowledge, there was no

previous study to evaluate the analgesic effect locally

infiltrated tramadol, bupivacaine, and pethidine after

cesarean delivery. Therefore, we designed the present

study to assess the effect of pethidine, tramadol, and

bupivacaine wound infiltration before skin closure

on postoperative pain relief in patients candidate for

cesarean delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After institutional approval and obtaining an informed

patient consent, 120 ASA physical status I-II females,

scheduled for elective cesarean section under spinal

anesthesia, were included in the study. We excluded

patients with suspected or manifest bleeding

disturbances, allergy to bupivacaine, tramadol or

meperdine, atopia, diabetes mellitus, the presence of

liver or kidney diseases, abuse of drugs patients with

pregnancy-induced hypertension or pre-eclampsia,

bradycardia, arrhythmia, A-V nodal block. Before

the study began, a random-number table was used to

generate a randomized schedule specifying the group

to which each patient would be assigned upon entry

into the trial. In case of exclusion, the next patient

was randomized per schedule. In the operating room,

standard monitoring was applied (the lead II EKG,

Pulse oximetery and non-invasive blood pressure

monitor.) During the 10 minutes preceding the spinal

block, subjects were administered -10 cc/kg Ringer

2

lactate solution via an 18- gauge IV cannula. Spinal

anesthesia was performed in all patients at L2-L3 or

L3-L4 or L4-L5 interspace with the patients in the

sitting position using a 25- gauge whitacre needle.

The block was done with 2.5 cc hyperbaric bupivacaine

0.5% in dextrose 8.25%. After injection, the parturient

was turned to a supine position, and the operating

table was tilted to the left. The sensory block to

pinprick was repeatedly tested.

A block level of T4 to T6 was required before surgery

started, which took place 15 minutes after injection.

The cesarean delivery was performed and at the time

of skin closure, while still on the operating table,

patients were randomly allocated to 1 to 4 groups.

Each group consisted of 30 parturientes: Patients

in group P received pethidine 50 mg, in group T

treated with tramadol 40 mg, in group B treated

with bupivacaine 0.25% 0.7 mg/kg, and in group C

received 20 ml normal saline injection in incision

site of surgery. All drugs were diluted with sterile

normal saline to give 20 ml solutions, which were

administered intraincisionally. Also, all drugs were

labeled with the randomization number of the patient.

Drug administration began at the time of skin closure.

Patients and staff involved in data collections were

unaware of the patient group assignment. In case of

emergency, the anesthesiologist who was responsible

for the patient had ready access to the nature of the

drugs administered to the patient. On arrival in

recovery room, pain intensity at rest and on coughing

was assessed by visual analogous scale (VAS) ranging

from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) and

then 15, 30, 60 minutes and 2, 6, 12, 24 hours after

arrival in the recovery. If analgesia was considered

inadequate at any stage, the anesthesiologist could

give additional bulous of morphine 0.08 mg/kg until

VAS was <3. Recovery time (the time between arrival

and discharge of parturient from the recovery room)

was assessed based on Modified Aldretes Score[9] for

all the patients in 4 groups. The frequency of nausea

and vomiting, mean arterial blood pressure, drug

side effects, metoclopramide and opioid consumption,

sedation score evaluated at the same time. Sedation

was monitored using the following scale: 1 = alert;

2 = occasionally drowsy; 3 = frequently drowsy; 4

= sleepy, easy to arouse; 5 = somnolent, difficult

to arouse. Nausea or vomiting was managed with

metoclopramide 0.15 mg/kg as necessary. At the end of

the 24 hours, patients were asked their overall opinion

of the quality of pain relief they had received using the

following- excellent; very good; good; poor. A sample

size of 120 patients (4 groups of 30) was calculated

to be required with standard errors 0.05, a power of

0.95 and d = 1.2 based on previous relevant clinical

data. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Jabalmeli, et al.: Intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine, bupivacaine analgesia

version 10 software using Chi-Square, ANOVA, and

Kruskal-wallis tests. Values for quantitative variables

were reported as mean SD (standard deviation), and

for qualitative variables as count and percent. A value

of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 4, the incidence of nausea and vomiting, and

metoclopramide consumptions was similar for all

groups. Patients satisfaction was significantly higher

in groups P and T when compared with groups B

and C [Table 3]. Sedation scores were similar for all

groups (P > 0.05). None of the patients had sedation

scores more than 3 during 24 hours postoperatively.

3 patients complained of shivering in group T. Also,

only 1 patient had tremor and hypotension in group T.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), and respiratory

rate (PR) were not different between the 4 groups

during the study period [Table 5].

RESULTS

A total of 120 patients were studied. The 4 study

groups comparable with respect to age, spinal

needling site and basal MAP, HR and RR, as well as

the obstetric history [Table 1]. Similarly, recovery

times and level of block were unaffected by patient

randomization [Table 2]. In all the times, VAS scores

both at rest and on coughing were significantly

different between the groups, except for 6 hours

postoperatively. Also, VAS scores were significantly

lower in groups tramadol (T) and meperidine (P)

compared with groups bupivacaine (B) and control (C),

except for 24 hours (VAS at rest) and 6 hours (VAS

on coughing) postoperatively. [Table 3] VAS scores

at rest were significantly lower in group P compared

with group T at 0, 15, 30 minutes and 24 hours

postoperatively. Also, VAS scores, on coughing, were

significantly lower in group P compared with group T

at 0, 15 minutes, 1, 2, and 24 hours postoperatively.

The number of patients requiring morphine were

significantly (P < 0.05) different between the

groups (105 mg vs. 87, 56, 46 mg for groups control,

bupivacaine, tramadol, and pethidine, respectively) in

all the times, except for 2 and 6 hours postoperatively.

None of the patients received morphine more than

1 dose (0.08 mg/kg) when VAS 3 postoperatively.

The percentage of morphine administration at the

different times is shown in Table 3. As shown in

DISCUSSION

We performed a double-blind, prospective, randomized

study to compare the effect of subcutaneous bupivacaine,

meperidine, and tramadol on postoperative pain relief,

morphine requirements, patients satisfaction and

side effects after an elective cesarean section. Our

data showed that VAS scores both at rest and on

coughing were significantly lower in groups P and

T when compared with groups B and C. Previous

works demonstrated that, subcutaneously tramadol

provided local anesthesia equal to lidocaine in patients

undergoing minor surgery (lipoma excision and

scar revision) under local anesthesia.[11] Moreover,

tramadol extended the pain-free period after operation

and significantly decreased the need for postoperative

analgesia.[11] Also, it was shown that tramadol had

a local anesthetic effect similar to that of prilocaine

after intradermal injection.[10] Initially, it was thought

that tramadol produced its anti-nociceptive and

analgesic effects through spinal and supraspinal sites

rather than via a local anesthetic action.[12] However,

Table 1: Demographics data of patients (Mean MAP, RR, PR) before intervention and spinal needling site in 4 groups

Age (year)

MAP (mmHg)

PR (beta/min)

RR (rate)

L4-L5

Spinal needling site L3-L4

(N %) L2-L3

B n = 30

27.1 4.9

80 0.6

89 8

11 1

0-0

18-(60)

12-(40)

P n = 30

26.5 3.9

78 0.6

89 10

12 2

0-0

18-(60)

12-(40)

T n = 30

26.3 4.7

79 0.4

90 4

11 0.9

2-(6.7)

15-(50)

13-(43.3)

C n = 30

26.6 4.5

80 0.6

92 6

11 1

2-(6.7)

15-(50)

13-(43.3)

P value

> 0.05

0.45

0.42

0.18

0.98

MAP = Mean arterial pressure; PR = Pulse rate; RR = Respiratory rate data (Age MAP, PR, RR) are as Mean SD

Table 2: Recovery time, level of spinal block, Mean MAP, RR, PR after in 4 groups

Recovery time {mean SD (minutes)}

Level of block (n,%)

T4

T5

T6

MAP (mmHg)

RR (rate/min)

B (Bupivacaine) n = 30

74 14

P (Pethidine) n = 30

82 19

T (Tramadol) n = 30

71 12

C (Control) n = 30

69 11

P value

0.06

18-(60)

10 (33.3)

2 (6.7)

78.1 0.3

11 0.5

15-(50)

11 (36.7)

4-(13.3)

77.7 .30

11 0.7

21-(70)

9-(30)

0-0

77.4 0.2

10.7 0.4

18-(60)

11-(7.36)

1-(3.3)

78.5 0.3

10.9 0.5

0.19

0.33

0.07

MAP = Mean arterial pressure; PR = Pulse rate; RR = Respiratory rate

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3 3

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Jabalmeli, et al.: Intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine, bupivacaine analgesia

Table 3: VAS at rest and on coughing and frequency of morphine consumption at recovery o, 15', 30', 60', 2, 6, 12, 24 hours

postoperative in the 4 groups

15'

B n = 30

2.2 0.5

2 0.2

P n = 30

1.8 0.5

1.8 0.4

30'

2.2 0.5

60'

2h

6h

12 h

24 h

On coughing (0)

2.6 0.7

15'

2.9 1

31

3.6 1

2.3 0.7

2.6 1

2.1 0.6

30'

2.8 1.3

60'

2h

6h

12 h

24 h

Morphine consumption (% of total patients in each group)

(0)

15

30

60

2h

6h

12 h

24 h

3.7 1.5

3.7 1.7

3.8 1.9

4.7 2.1

2.8 1.4

26.7

6.7

23.3

46.7

53.3

46.7

66.7

23.3

VAS (mean SD)

Rest (0)

T n = 30

20

20

C n = 30

2.2 0.5

2.3 0.4

P value

0.01

< 0.001

1.9 0.4

20

2.7 0.8

< 0.001

2.1 0.6

2 0.5

2.7 0.9

0.001

2.5 0.6

2.7 0.9

3.1 0.9

2.1 0.4

1.9 0.5

1.8 0.4

2.4 0.5

2.5 0.6

2.5 0.6

2.4 0.6

20

20

2.7 0.9

2.7 1

3.8 1

2.3 0.5

2.5 1

2.8 1.1

0.02

0.11

< 0.001

0.05

< 0.001

< 0.001

2.1 0.5

20

3.5 1.5

< 0.001

2.2 0.7

2.4 0.6

3.6 1.4

< 0.001

2.9 1

3.2 1.4

3.3 1.4

2.2 0.8

3.5 0.8

3 1.1

3.2 1

31

3.8 1.7

3.9 1.7

5.2 1.5

3 1.2

0.02

0.04

< 0.001

0.05

0

0

3.3

10

33.3

33.3

60

6.7

0

0

0

6.7

46.7

50

40

43.3

20

26.7

53.3

40

46.7

53.3

76.7

33.3

0.001

< 0.001

< 0.001

< 0.001

0.23

0.21

0.01

0.01

VAS = Visual analogous scale

Table 4: Frequency of side effects, metoclopramide consumption,

and satisfaction scores in the 4 groups

Side effects

Nausea (n, %)

Vomiting (n, %)

Metoclopramide

consumption (n, %)

Satisfaction scores

Poor

good

Very good

Excellent

B (%)

10-33

10-33

10-33

P (%)

11-22

9-30

9-30

T (%)

10-33

10-33

10-33

C (%)

12-40

12-40

12-40

10-33

20-66.7

0

0

6-20

21-70

2-6.7

1-3.3

5-16.7

24-80

1-3.3

0

21-70

9-30

0

0

several clinical studies have shown that it might have

peripheral local anesthetic type properties.[13-16] By

direct tramadol application to the sciatic nerve in rats,

it was proven that tramadol exerts a local anesthetic

type effect.[15] In the present study, tramadol had a

local anesthetic action similar to that of bupivacaine

and because of its anti-nociceptive effect, it could

extend the postoperative pain-free period. When

extracellular sodium concentration decreases, the

nerve fiber becomes sensitive to local anesthetics.[17].

Jou etal. suggested that tramadol affects sensory and

motor nerve conduction by a similar mechanism to

that of lidocaine, which acts on the voltage-dependent

4

sodium channel, leading to an axonal blockage.[18]

However, Mert etal. proposed that tramadol might

have a mechanism, different from that of lidocaine

for producing conduction blocks, the presence of a

large Ca2+ concentration in the external medium

increases tramadols activity whereas decreasing

lidocaine activity.[19] Tramadol is structurally-related

codeine, which is, in fact, a methyl-morphine.[16,20]

Tramadol exerts its action on central monoaminergic

systems, and this mechanism may contribute to its

analgesic effect.[20] After IM injection, tramadol was

rapidly and almost completely absorbed, and peak

serum concentrations were reached in 45 minutes on

average;[21] subcutaneous pethidine infusion analgesia

has advantage over conventional intramuscular bolus

injections. It was judged acceptable to both patients

and ward staff.[22] The findings of the other studies in

this regards is in accordance with the results of our

study. In our study, the total amount of consumed

analgesic in the postoperative period was considerably

less in groups P and T compared with groups B and

C, respectively.

Bupivacaine wound instillation induced relatively poor

post-cesarean analgesia.[23] It should be remembered

that tissue response to surgery-induced injury initiates

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Jabalmeli, et al.: Intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine, bupivacaine analgesia

Table 5: Mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg), heart rate (beta/min) and respiratory rate (rate/min) at the recovery (0), 15, 30,

60, 2, 6, 12, 24 hours postoperative in the 4 groups

B

P

T

MAP

HR

PR (mean MAP (mean HR (mean RR (mean MAP (mean HR (mean RR (mean

(mean (mean SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

SD)

0

0.4074 75 6 10 0.8

72 0.5

77 8

10 2

72 0.3

77 3

10 1

15 75 0.5

84 6

10 0.6

75 0.6

83 1

10 1

75 0.3

83 3

10 2

30 76 0.5

83 6

11 1.0

78 0.5

83 8

10 1

75 0.4

84 6

10 1

60

79 6

85 8

12 1

79 0.5

85 8

12 2

78 0.4

84 5

12 1

2h

80 0.6

89 8

11 1

78 0.6

9010

12 2

79 0.4

90 4

11 0.9

6h

80 0.5

89 8

12 1

80 0.6

90 13

12 2

80 0.3

89 5

12 1

12 h 80 0.8

92 9

11 2

80 0.9

9011

11 1

80 0.3

90 5

11 1

24 h 80 0.4

87 6

11 1

80 0.5

85 9

112

80 0.2

85 5

11 0.9

C

MAP

HR (mean

(mean

SD)

SD)

74 0.5

78 6

75 0.5

85 9

78 0.5

86 8

78 0.5

87 7

80 0.6

92 6

80 0.6

91 6

80 0.6

92 7

80 0.5

87 6

RR (mean

SD)

10 0.8

10 0.7

10 1

12 1

11 1

12 1

11 2

11 0.9

MAP = Mean Arterial pressure; HR = Heart rate; RR = Respiratory rate

in nociception, inflammation, and hyperalgesia.[24,25]

Thus, it is not surprising that agents with different

mechanisms of action modulate this cascade.

Local anesthetic agents modulate peripheral pain

transduction by inhibiting the transmission of noxious

impulses from the site of injury. [23] Furthermore,

despite the fundamental differences in mechanism of

action, basic science investigations suggest that both

local anesthetic agents and opioids decrease peripheral

and central sensitization via direct central nervous

system effect. [9] As our study showed, one study

demonstrated that subcutaneous wound infiltration

with bupivacaine 0.5% did not decrease morphine

requirements on the first postoperative day after lower

segment cesarean section.[26]

The frequency of nausea, sedation, and metoclopramide

consumptions was low and not significantly different

among the 4 groups. Nausea and vomiting have been

major side effects of opioid used for postoperative

analgesia.[9] Tramadol appeared to cause substantially

more postoperative nausea and vomiting than

morphine.[27]

The mutagenic effect of tramadol is well-described

and recognized as one of its more troublesome side

effects.[28-30] The rate of titration of the opioids dose,

rather than target dose, is the major determinant

of a patients tolerability.[31,32] In our study, patient

satisfaction was significantly higher in groups P and

T when compared with groups B and C [Table 4].

However, it should be remembered that the analgesic

efficacy is likely dependent upon multiple variables.

First, it is possible that by altering the volume and

concentration of the drug administered, an improved

analgesia may be achieved. Second, the relative

efficacy of the analgesic regimens investigated is

study design-dependent.[23] Therefore, we suggest

that by altering the delivery set-up, different results

may be achieved. However, this hypothesis requires

further investigations. Again, no difference was found

between groups in mean arterial blood pressure, and

respiratory rate. This finding is comparable to other

studies.[11,22,23,26] Our study challenges some of the

claimed clinical differences between pethidine and

tramadol. It demonstrates that the effectiveness of

pethidine is similar to tramadol. Therefore; we suggest

altering the study design and further investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to sincerely thank the support of all the

colleagues in Beheshti Hospital Medical Center affiliated

to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran.

Furthermore, our special thanks go to the patients who

wholeheartedly and actively assisted us to carry out this

research. No conflict of interest existed. We thank Mrs.

Tahery and the nurses at the Post-anesthesia Care Unit for

their contribution to the study.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

McIntosh DG, Rayburn W. Patient-controlled analgesia in obstetrics

and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78:1129-35.

Greene NM. Distribution of local anesthetic solutions within the

subarachnoid space. Anesth Analg 1985;64:715-30.

Eisenach J, Grice S, Dewan D. Patient-controlled analgesiafollowing

cesarean section: A comparison with epidural and intramuscular

narcotics. Anesthesiology 1988;68:444-8.

Harrison D, Sinatra R, Morgese L, Chung J. Epidural narcotic

and patient-controlled analgesia for cesarean section pain relief.

Anesthesiology 1988;68:454-7.

Sharma S, Sidawi E, Ramin S, Lucas M, Leveno K, Cunningham G.

Cesarean delivery- A randomized trial of epidural versus patientcontrolled meperidine analgesia during labour. Anesthesiology

1997;87:487-97.

Stein C. The control of pain in peripheral tissue by opioids. N Engl J

Med 1995;332:1685-90.

Heard SO, Edwards WT, Ferrari D, Hanna D, Wong PD, Liland A,

etal. Analgesic effect of intraarticular bupivacaine or morphine after

arthroscopic knee surgery: A randomized, prospective, double-blind

study. Anesth Analg 1992;74:822-6.

Picard PR, Tramer MR, McQuar HJ, Moore RA. Analgesic efficacy of

peripheral opioids (all except intra-articular): A qualitative systematic

review of randomized controlled trialls. Pain 1997;72:309-18.

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3 5

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.advbiores.netonThursday,October11,2012,IP:39.214.128.6]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Jabalmeli, et al.: Intraincisional injection tramadol, pethidine, bupivacaine analgesia

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

Fukuda K. Intravenous opioid anesthetics. In: Miller RD, editor.

Millers Anesthesia. 6th edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevirer

Churchill Livingstons; 2005. p. 415.

Atunkaya H, Ozer Y, Kargi E, Babuccu O. Comparison of local

anaesthetic effects of tramadol with prilocaine for minor surgical

procedures. Br J Anaesth 2003;90:320-2.

Altunkaya H, Ozer Y, Kargi E, Ozkocak I, Hosnuter M, Demirel CB,

etal. The postoperative Analgesic effet of tramadol when used as

subcutaneous local Anesthetic. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1461-4.

Langlois G, Estbe JP, Gentili ME, Kerdils L, Mouilleron P, Ecoffey C.

etal. The addition of tramadol to lidocaine does not reduce tourniquet

and postoperative pain during IV regional anesthesia. Can J Anaesth

2002;49:165-8.

Pang WW, Huang PY, chang DP, Huang MH. The peripheral analgesic

effect of tramadol in reducing propofol injection pain: A comparison

with lidocaine. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1999;24:246-9.

Acalovschi I, Cristea T, Margarit S, Gavrus R. Tramadol added to lidocaine

for intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2001;92:209-14.

Kapral S, Gollmann G, Waltl B, Likar R, Sladen RN, Weinstabl C, etal.

Tramadol added to mepivacaine prolongs the duration of an axillary brachial

plexus blockade. Anesth Analg 1999;88:853-6.

Wagner LE II, Eaton M, Sabnis SS, Gingrich KJ. Meperidine and lidocaine block

of recombinant voltage-dependent Na+channels: Evidence that meperidine is

a local anesthetic. Anesthesiology 1999;91:1481-90.

Jou IM, Chu KS, Chen HH, Chang PJ, Tsai YC. The effects of intrathecal

tramadol on spinal somatosensory evoked potentials and motor evoked

responses in rats. Anesth Analg 2003;96:783-8.

Mert T, Gunes Y, Guven M, Gunay I, Ozcengiz D. Comparison of nerve

conduction blocks by an opioid and a local anesthetic. Eur J Pharmacol

2002;439:77-81.

Shipton EA. Tramadol: Present and future. Anaesth Intensive Care

2000;28:363-74.

Radbruch L, Grond S, Lehmann KA. A risk-benefit assessment of tramadol

in the management of pain. Drug Saf 1996;15:8-29.

Lintz W, Beier H, Gerloff J. Bioavailability of tramadol after i.m. injection in

comparison to i.v. infusion. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999;37: 175-83.

Gleeson RP, Rodwell S, Shaw R, Seligman SA. Post cesarean analgesia

using a subcutaneous pethidine infusion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1990;33:

13-7.

Zohar E, Shapiro A, Eidinov A, etal. Postcesarean analgesia: the efficacy

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

of bupivacaine wound instillation with and without supplemental diclofenac.

J Clin Anesth 2006;18:415-21.

Woolf CJ. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of acute pain. Br J

Anaesth 1989;63:139-46.

Woolf CJ, Chong MS. Preemptive analgesia: Treating postoperative pain

by preventing the establishment of central sensitization. Anesth Analg

1993;77:362-79.

Trotter TN, Hayes-Gregson P, Robinson S, Cole L, Coley S, Fell D. Wound

in filtration of local anesthetic after lower segment caesarean section.

Anaesthesia 199146:404-7.

Hopkins D, Shipton EA, Potgieter D, Van derMerwe CA, Boon J, De

WetC, etal. Comparison of tramadol and morphine via subcutaneous

PCA following major orthopedic surgery. Can J Anesthesia

1998;45:436-42.

Demiraran Y, IIce Z, Kocaman B, Bozkurt P. Does tramadol wound

infiltration offer an advantage over bupivacaine for postoperative

analgesia in children following herniotomy? Paediatr Anaesth

2006;16:1047-50.

Matkap E, Bedirli N, Akkaya T, Gm H. Preincisional local infiltration

of tramadol at the trocar site versus intravenous tramadol for pain

control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Anesth 2011;23:197201. Epub 2011 Apr 16.

Khajavi MR, Aghili SB, Moharari RS, Najafi A, Mohtaram R,

KhashayarP, etal. Subcutaneous tramadol infiltration at the wound

site versus intravenous administration after pyelolithotomy. Ann

Pharmacother 2009;43:430-5.

Ayatollahi V, Behdad S, Hatami M, Moshtaghiun H, BaghianimoghadamB.

Comparison of peritonsillar infiltration effects of ketamine and

tramadol on post tonsillectomy pain: A double-blinded randomized

placebo-controlled clinical trial. Croat Med J 2012;53:155-61.

Kasapoglu F, Kaya FN, Tuzemen G, Ozmen OA, Kaya A, Onart S.

Comparison of peritonsillar levobupivacaine and bupivacaine

infiltration for post-tonsillectomy pain relief in children: Placebocontrolled clinical study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75:322-6.

Epub 2010 Dec 18.

Source of Support: Anesthesiology and Critical Care Research Center,

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Conflict of Interest:

None declared.

Advanced Biomedical Research | July - September 2012 | Vol 1 | Issue 3

You might also like

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol294459-335648 091924 PDFDocument6 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol294459-335648 091924 PDFaltaikhsannurNo ratings yet

- Anasthesia in Obese PatientDocument4 pagesAnasthesia in Obese PatientWaNda GrNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument8 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Clonidin Vs Tramadol For Post Spinal ShiveringDocument4 pagesClonidin Vs Tramadol For Post Spinal ShiveringAndi Rizki CaprianusNo ratings yet

- My Thesis Protocol-4Document15 pagesMy Thesis Protocol-4Rio RockyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0104001413001127 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0104001413001127 MainFrederica WiryawanNo ratings yet

- Analgesic 3Document7 pagesAnalgesic 3Indra T BudiantoNo ratings yet

- Anesth Essays ResDocument8 pagesAnesth Essays ResFi NoNo ratings yet

- EtamolDocument5 pagesEtamolthonyyanmuNo ratings yet

- Efficacy Lidocaine Endoscopic Submucosal DissectionDocument7 pagesEfficacy Lidocaine Endoscopic Submucosal DissectionAnonymous lSWQIQNo ratings yet

- Arp2017 5627062Document6 pagesArp2017 5627062sujidahNo ratings yet

- Effects of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on postoperative pain after gastrectomyDocument33 pagesEffects of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on postoperative pain after gastrectomyJuwita PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Anes 10 3 9Document7 pagesAnes 10 3 9ema moralesNo ratings yet

- A ComparativeDocument5 pagesA ComparativedeadanandaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Article 369Document6 pages2014 Article 369pebinscribdNo ratings yet

- 2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024Document6 pages2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024shivamNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Bolus Administration of Continuous Intravenous Lidocaine On Pain Intensity After Mastectomy SurgeryDocument6 pagesEffectiveness of Bolus Administration of Continuous Intravenous Lidocaine On Pain Intensity After Mastectomy SurgeryInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Kumar S.Document4 pagesKumar S.Van DaoNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument6 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Intrathecal and Intravenous Morphine For Analgesia After HepatectomyDocument10 pagesA Comparison of Intrathecal and Intravenous Morphine For Analgesia After Hepatectomyvalerio.messinaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Fentanyl Patch Post OpDocument8 pagesJurnal Fentanyl Patch Post OpChintya RampiNo ratings yet

- The Prophylactic Effect of Rectal Diclofenac Versus Intravenous Pethidine On Postoperative Pain After Tonsillectomy in ChildrenDocument7 pagesThe Prophylactic Effect of Rectal Diclofenac Versus Intravenous Pethidine On Postoperative Pain After Tonsillectomy in ChildrenNi Komang Suryani DewiNo ratings yet

- Arp2017 5627062Document6 pagesArp2017 5627062Syamsi KubangunNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S111018491630023X MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S111018491630023X MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Ponv InternasionalDocument8 pagesPonv InternasionalRandi KhampaiNo ratings yet

- Analgesic Efficacity of Pfannenstiel Incision Infiltration With Ropivacaine 7.5Mg/Ml For Caesarean SectionDocument17 pagesAnalgesic Efficacity of Pfannenstiel Incision Infiltration With Ropivacaine 7.5Mg/Ml For Caesarean SectionboblenazeNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 118Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 118Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Analgesic Effects of Intravenous Nalbuphine and Pentazocine in Patients Posted For Short-Duration Surgeries A Prospective Randomized Double-Blinded StudyDocument4 pagesComparison of Analgesic Effects of Intravenous Nalbuphine and Pentazocine in Patients Posted For Short-Duration Surgeries A Prospective Randomized Double-Blinded StudyMuhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- PRM2017 1721460 PDFDocument6 pagesPRM2017 1721460 PDFmikoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyDocument8 pagesImpact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyMiftah Furqon AuliaNo ratings yet

- Musa Shirmohammadie, Alireza Ebrahim Soltani, Shahriar Arbabi, Karim NasseriDocument6 pagesMusa Shirmohammadie, Alireza Ebrahim Soltani, Shahriar Arbabi, Karim Nasseridebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Morfina IT. Dosis Bajas en HTADocument8 pagesMorfina IT. Dosis Bajas en HTAChurrunchaNo ratings yet

- Dolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioDocument7 pagesDolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioChurrunchaNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument6 pagesJurnalFitri Aesthetic centerNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument14 pagesSynopsisAqeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology of acute pain randomized trialsDocument2 pagesPharmacology of acute pain randomized trialsOmar BazalduaNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryDocument7 pagesJournal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Effect of Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine On Post-Craniotomy PainDocument9 pagesEffect of Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine On Post-Craniotomy PainIva SantikaNo ratings yet

- Ircmj 15 9267Document6 pagesIrcmj 15 9267samaraNo ratings yet

- JCM 08 02014 v2Document9 pagesJCM 08 02014 v2burhanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Ondansetron, Cyclizine and Prochlorperazine For PONV Prophylaxis in Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDocument5 pagesComparison of Ondansetron, Cyclizine and Prochlorperazine For PONV Prophylaxis in Laparoscopic CholecystectomynikimahhNo ratings yet

- Dr._Nataraj__EJCM-132-1888-1893-2023Document7 pagesDr._Nataraj__EJCM-132-1888-1893-2023vithz kNo ratings yet

- IV Acetaminophen for Pelvic Organ Prolapse SurgeryDocument15 pagesIV Acetaminophen for Pelvic Organ Prolapse SurgeryFeliana ApriliaNo ratings yet

- J000Document8 pagesJ000blabarry1109No ratings yet

- Multimodal Postoperative Analgesia: Combinations of Analgesics After Abdominal Surgery at Chu - Jra AntananarivoDocument11 pagesMultimodal Postoperative Analgesia: Combinations of Analgesics After Abdominal Surgery at Chu - Jra AntananarivoIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- 与扑热息痛联用增效Document5 pages与扑热息痛联用增效zhuangemrysNo ratings yet

- TAP Paper PublishedDocument8 pagesTAP Paper PublishedMotaz AbusabaaNo ratings yet

- Etm 17 6 4723 PDFDocument7 pagesEtm 17 6 4723 PDFLuthfi PrimadaniNo ratings yet

- Topical Nifedipine With Lidocaine Ointment Versus Active Control For Pain After Hemorrhoidectomy: Results of A Multicentre, Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind StudyDocument8 pagesTopical Nifedipine With Lidocaine Ointment Versus Active Control For Pain After Hemorrhoidectomy: Results of A Multicentre, Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind StudykarisavnpNo ratings yet

- 4services On DemandDocument9 pages4services On DemandDe WiNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics AnesthesiaDocument31 pagesObstetrics AnesthesiaNorfarhanah ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Pre Emptive Oral Pregablin in Postop AnalgesiaDocument8 pagesPre Emptive Oral Pregablin in Postop AnalgesiaMotaz AbusabaaNo ratings yet

- Hyperbaric Spinal For Elective Cesarean Section: - Ropivacaine Vs BupivacaineDocument13 pagesHyperbaric Spinal For Elective Cesarean Section: - Ropivacaine Vs BupivacaineYayaNo ratings yet

- Original Contribution: Abd-Elazeem Elbakry, Wesam-Eldin Sultan, Ezzeldin IbrahimDocument6 pagesOriginal Contribution: Abd-Elazeem Elbakry, Wesam-Eldin Sultan, Ezzeldin IbrahimWALTER GARCÍA TERCERONo ratings yet

- KaratepeDocument5 pagesKaratepeJennifer GNo ratings yet

- Small-Dose Ketamine Infusion Improves Postoperative Analgesia and Rehabilitation After Total Knee ArthroplastyDocument6 pagesSmall-Dose Ketamine Infusion Improves Postoperative Analgesia and Rehabilitation After Total Knee ArthroplastyArturo AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol312191-1284204 033402Document5 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol312191-1284204 033402Rusman Hadi RachmanNo ratings yet

- Amalia 163216 - Journal ReadingDocument26 pagesAmalia 163216 - Journal ReadingGhifari FarandiNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDocument4 pagesEfficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDr shehwarNo ratings yet

- EVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYFrom EverandEVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYNo ratings yet

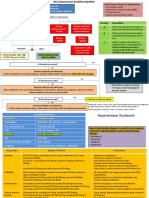

- Penatalaksanaan Hipertensi Terkini Fokus Pada JNC 8 - Wachid PutrantoDocument30 pagesPenatalaksanaan Hipertensi Terkini Fokus Pada JNC 8 - Wachid PutrantoVika Ratu100% (1)

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 pagesJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Jurnal DiareDocument4 pagesJurnal DiareSyukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin as an Early Diagnostic Tool for Neonatal SepsisDocument5 pagesProcalcitonin as an Early Diagnostic Tool for Neonatal SepsisSyukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 55 5 10Document5 pages55 5 10Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 55 5 11Document6 pages55 5 11Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 55 5 3Document4 pages55 5 3Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 55 5 2Document5 pages55 5 2Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 723168Document7 pages723168Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 723168Document7 pages723168Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- LicenseDocument13 pagesLicenseShafilka IsmailNo ratings yet

- 723168Document7 pages723168Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- 11Document7 pages11Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- Nitrous Oxide Diffusion and The Second Gas Effect.26Document7 pagesNitrous Oxide Diffusion and The Second Gas Effect.26Syukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AnestesiDocument5 pagesJurnal AnestesiSyukron AmrullahNo ratings yet

- JOI Vol 7 No 5 Juni 2011 (Reni P)Document4 pagesJOI Vol 7 No 5 Juni 2011 (Reni P)Syahrial Laskar PelangiNo ratings yet

- Kedaruratan ObstetriDocument2 pagesKedaruratan ObstetriAsrori AzharNo ratings yet

- Injeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreDocument5 pagesInjeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreHerdy ArshavinNo ratings yet

- Theories of Grief and AttachmentDocument4 pagesTheories of Grief and AttachmentbriraNo ratings yet

- Week 6 - LP Modeling ExamplesDocument36 pagesWeek 6 - LP Modeling ExamplesCharles Daniel CatulongNo ratings yet

- Co General InformationDocument13 pagesCo General InformationAndianto IndrawanNo ratings yet

- PancreatoblastomaDocument16 pagesPancreatoblastomaDr Farman AliNo ratings yet

- Brand Analysis of Leading Sanitary Napkin BrandsDocument21 pagesBrand Analysis of Leading Sanitary Napkin BrandsSoumya PattnaikNo ratings yet

- Swan-Ganz Catheter Insertion GuideDocument3 pagesSwan-Ganz Catheter Insertion GuideJoshNo ratings yet

- Day Care Center Grant ProposalDocument16 pagesDay Care Center Grant ProposalSaundra100% (1)

- Dat IatDocument4 pagesDat Iatscribd birdNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesEffectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaIwanNo ratings yet

- Interactive CME Teaching MethodsDocument5 pagesInteractive CME Teaching MethodsROMSOPNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic BrochureDocument4 pagesCosmetic BrochureDr. Monika SachdevaNo ratings yet

- Science of 7 ChakraDocument6 pagesScience of 7 ChakraSheebaNo ratings yet

- A. Define Infertility: Objectives: Intended Learning Outcomes That TheDocument2 pagesA. Define Infertility: Objectives: Intended Learning Outcomes That TheJc Mae CuadrilleroNo ratings yet

- Competitive Tennis For Young PlayersDocument146 pagesCompetitive Tennis For Young PlayersTuzos100% (1)

- Tack Welding PowerPointDocument94 pagesTack Welding PowerPointCheerag100% (1)

- Summer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsDocument30 pagesSummer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsBiswadeep PurkayasthaNo ratings yet

- Biogas (Methane) EnglishDocument8 pagesBiogas (Methane) Englishveluthambi8888100% (1)

- Local Conceptual LiteratureDocument3 pagesLocal Conceptual LiteratureNatasha Althea Basada LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Report SampleDocument11 pagesReport SampleArvis ZohoorNo ratings yet

- Veritas D1.3.1Document272 pagesVeritas D1.3.1gkoutNo ratings yet

- Anarchy RPG 0.2 Cover 1 PDFDocument14 pagesAnarchy RPG 0.2 Cover 1 PDFanon_865633295No ratings yet

- JUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1Document2 pagesJUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1joselito papa100% (1)

- Resolve Family Drainage CatetherDocument16 pagesResolve Family Drainage CatetherradeonunNo ratings yet

- Case Control Study For MedicDocument41 pagesCase Control Study For Medicnunu ahmedNo ratings yet

- 1 - DS SATK Form - Initial Application of LTO 1.2Document4 pages1 - DS SATK Form - Initial Application of LTO 1.2cheska yahniiNo ratings yet

- Community and Public Health DefinitionsDocument3 pagesCommunity and Public Health DefinitionsSheralyn PelayoNo ratings yet

- Detailed Advertisement of Various GR B & C 2023 - 0 PDFDocument47 pagesDetailed Advertisement of Various GR B & C 2023 - 0 PDFMukul KostaNo ratings yet

- Radiographic Cardiopulmonary Changes in Dogs With Heartworm DiseaseDocument8 pagesRadiographic Cardiopulmonary Changes in Dogs With Heartworm DiseaseputriwilujengNo ratings yet

- Ba - Bacterial Identification Lab WorksheetDocument12 pagesBa - Bacterial Identification Lab WorksheetFay SNo ratings yet