Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heroic Athlete in Ancient Greece

Uploaded by

jbmcintoshCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Heroic Athlete in Ancient Greece

Uploaded by

jbmcintoshCopyright:

Available Formats

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

The Heroic Athlete in

Ancient Greece

DAVID J. LUNT

Departments of History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies

The Pennsylvania State University

In ancient Greece, powerful and successful athletes sought after and displayed

might and arete (excellence) in the hope of attaining a final component of divinityimmortality. These athletes looked to the heroes of Greek myth as models for their own quests for glory and immortality. The most attractive heroic

model for a powerful athlete was Herakles. Milo of Croton, a famed wrestler

from antiquity, styled himself after Herakles and imitated him in battle. In

addition, three athletes from the fifth century B.C., Theagenes, Euthymos, and

Kleomedes, made the transition, in Greek minds, from athlete to hero. The

power, might, and arete of their athletic victories provided the justification for

their subsequent heroization. The stories of these athletes shed light on how

historical athletes sought to imitate their mythic predecessors and how ancient

Greeks were willing to bestow heroic honors, such as religious cults, on powerful

victorious athletes.

HE ANCIENT BIOGRAPHER PLUTARCH WROTE that three characteristics distinguished

divinity, and those who sought itpower or might, excellence (arete), and immortality.1

In ancient Greece, those who sought divinity, especially successful athletes, strove to display

Correspondence to lunt@psu.edu. A shorter version of this paper won the North American Society

for Sport History Graduate Student Essay Award in 2008. The author would like to thank Mark Dyreson,

Bettina Kratzmller, Donald Kyle, Mark Munn and the JSH editorial team for their critical suggestions

and thoughtful assistance.

Fall 2009

375

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

might and arete in the hope of attaining the final component of divinityimmortality.

By means of their athletic prowess and victories, athletes sought and displayed arete, a

complicated Greek word that referred to virtue, excellence, and general superiority. While

complete equality with the awesome gods of Olympus was beyond their reach, ancient

Greek athletes looked to the race of the mythic heroes as models for their own quests for

glory and immortality.

Around 700 B.C., during Greeces Archaic Period, the poet Hesiod, in recounting the

various ages of existence, described an age of heroes or demi-gods, where a divine race

of heroic men had fought great wars and earned a blessed afterlife.2 Plutarch, in his Life

of Thesesus, speculated that Theseus era had produced a race of beings that far surpassed

normal human athletic abilities such as bodily strength and swiftness of foot.3 Some of

the members of this race of heroes demonstrated such a degree of might and virtue through

their exploits, adventures, and achievements that they somehow achieved a measure of

immortality, meriting the establishment of religious cults after their deaths and continuing to exert some type of influence on earth. To the ancient Greeks, the mythic heroes,

such as Theseus, Herakles (Hercules in the Latinized form), Pelops, and Achilles really

lived and died. As noted myth scholar Paul Veyne explained, the mythic heroes were

human beings who possessed supernatural and superhuman traits. There was no room for

the ancient Greeks to doubt the reality of the lives of the great mythic heroes since human

beings still existed and perhaps had always existed.4 Thus, by imitating the lives and

adventures of these mythic heroes, successful and powerful athletes in ancient Greece

could aspire to achieve a like measure of heroic honors after death.

Modern scholarship has fueled a considerable amount of debate concerning the nature of these ancient Greek athlete-heroes. Pausanias and Plutarch, two of the principal

ancient sources for these fifth-century B.C. athletes, wrote much later, in the second century A.D. While these writers chronological distance does not disqualify them as reliable

sources, it is a task for the modern scholar to determine how soon after the athletes death

the ancient Greeks instituted heroic honors. In addition, mythic tropes and folkloric

themes pepper the stories associated with these athletes, making it difficult to assess which

components of these stories are historical and which are mythic. Finally, some scholars

have conjectured that the athletic nature of these figures was not the primary reason for

their heroization.

Despite these debates and difficulties, the stories of these mortal athletes-turned-heroes provide valuable information for understanding the importance of athletic achievement in ancient Greece. In 1968, the American scholar Joseph Fontenrose compiled a

series of athlete-hero stories from ancient Greece and boiled them down to their essential

elements, focusing especially on the mythic similarities among them. By examining the

common themes and elements in these accounts, Fontenrose arrives at a type or model for

the ancient Greek athletic hero. Fontenrose identifies fourteen themes in the various

versions of common athlete-hero stories and, with considerable effort, links them to one

another and to the general Greek mythic tradition. While Fontenroses compilation represented an important step in collecting and analyzing these stories of historical athletesturned-heroes, his numerous connections to mythic tropes belied an assumption that the

legends of folklore posthumously attached themselves to the historical athletes.5 This

376

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

assumption, however, did not allow for the possibility that the historical athletes had consciously attempted to imitate the actions and adventures of the mythic heroes in order to

claim a similar heroic status. If this were the case, the athletes themselves would be, to

some extent, responsible for the parallels between their lives and those of the heroes. In

addition, as classicist Leslie Kurke notes, Fontenrose proposes no explanation for why

these athletes assumed or received heroic honors.6

In a 1979 publication, Franois Bohringer revisits the issue of the hero-athlete, and

seeks to explain why certain victorious athletes achieved heroic cult and others did not.

Bohringer appropriately notes that many of these mortals-turned-heroes were important

military and political figures in their communities independently of their athletic successes, and that ancient Greek communities honored these important citizens as heroes in

order to obscure periods of political or social weakness and division.7 Nevertheless,

Bohringers explanation for why some athletes received heroic honors and others (apparently) did not is too simplistic. He contends that those who received no heroic cult lived

in cities that experienced no duress during or shortly after the athletes lifetime.8 Although

he hints that some athletes may have expressly identified themselves with heroic figures in

leading their cities, and that cultic honors seem to have been instituted quite early for

some athletes, Bohringer focuses on the role of the cities in exalting individual athletes in

order to smooth over collective weaknesses and crises.9 While Bohringers conclusions

might have explained why some athletes received posthumous heroic honors and others

did not, they do not address whether the athletes actively sought to participate in this

process; nor does he account for the athlete who imitated the heroes, but never received

posthumous honors.10

Recently, Oxford classicist Bruno Currie has examined how ancient literary sources

situated many of these heroized athletes in the fifth century B.C., and the archaeological

evidence, although slightly later in date, nevertheless indicates cult activity for some athlete-heroes in the fourth century B.C. This relative proximity between the institutions of

cult to their lifetimes implies that these athletes understood heroization to be a possibility,

and that their athletic successes might provide an avenue to heroization.11 Just as athletic

prowess was an important component of heroic identity in ancient Greece, so too was

heroic action an important prerequisite for an athlete who sought heroic immortality.

From all these treatments, there emerges a type of rough blueprint whereby a successful

athlete might achieve heroic recognition. This process, established by the stories of the

mythic heroes and neatly encapsulated by Plutarchs observation concerning divinity and

its seekers, requires victory in contestsathletic and otherwiseand the public commemoration of these victories. These victories must demonstrate exceptional arete and

prowess in order for the athlete to lay any claim to the immortality afforded by heroic

honors.

Kurke has argued that victory, especially prominent victory in a major festival or

contest, brought kudos to the victor. This word, often translated as praise or renown,

carried additional meaning for the ancient Greeks. As understood traditionally, the possessor of kudos enjoyed special power bestowed by a god that makes a hero invincible.12

A victorious athlete claimed kudos from his victory and possessed a substantial amount of

this special heroic power. Understandably, athletic champions transferred the power of

Fall 2009

377

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

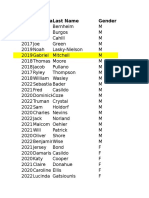

Scene on a terracotta bobbin attributed to the Penthesilea Painter (c.450 B.C.). Victory (Nik) offers a

ribbon to a victorious athlete, who wears a crown and holds a victory palm. Victory brought immense

prestige and kudos to an ancient Greek athlete. A few athletes who amassed massive amounts of victories

received posthumous heroic honors. COURTESY OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, FLETCHER FUND,

1928 (28.167). IMAGE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART. REPRODUCTION OF ANY KIND IS PROHIBITED WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION IN ADVANCE FROM THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART.

their heroic kudos from the athletic field to other endeavors, such as colonization and

war.13 Accordingly, the appropriation of kudos to athletic champions equated their achievements with the accomplishments of the heroes, and the Greeks regarded these kudoscharged athletes with both reverence and suspicion. The kudos of victory elevated human

athletes to a liminal status between mortals and gods, a status similar to that of the immortal heroes. In some cases, these super-humans, loaded with the kudos of their athletic

victories, claimed the powers of the mythic heroes and sought to imitate their deeds.

378

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

The most attractive heroic model for a powerful athlete was Herakles. Triumphant in

all sorts of contests, athletic and otherwise, in Greek mythology this demi-god achieved

immortality and was welcomed to Mount Olympus upon his death. Herakles provided

the ideal and ultimate example for a mortal athlete seeking immortality. Despite Bohringers

contention that the heroization of mortals had little to do with athletic success, the line

between victory in sport and victory in other endeavors was not well defined in ancient

Greece. Herakles achieved immortality due to his victories in many types of contests

sporting, military, and hunting. It was victory in these endeavors, according to the ancient

Greek conception of competition and triumph, which brought heroic status and eventual

immortality.14

Herakles drew his heroic identity from his many victories in both sporting and nonsporting contexts. Athletically, he was among the greatest of Greek champions. One

prominent tradition credited Herakles with re-founding the Olympic games and introducing the olive crown as a prize.15 In addition, several mythic episodes recount Herakles

prowess in wrestling. In many cases, the violence of Herakles throws killed or severely

injured those who challenged the great hero.16 This characterization of Herakles as a

powerful and accomplished wrestler held great cultural significance for the ancient Greeks.

He demonstrated his prowess and excellence through athletic competition, chiefly wrestling, and ancient Greek athletes sought to do the same. Herakles enjoyed victory in

athletic contexts, and his heroic identity, in part, stemmed from his success in these endeavors. Ancient Greek myths closely associated Herakles with the site, contests, and

prize for victory at Olympia, and his victories in wrestling further established his claim to

immortal heroic status. Herakles victories represented an integral component of his supernatural status and subsequent immortalization.

Notwithstanding these achievements in what moderns would consider sport, the

ancient Greeks conceived of Herakles as an athlete on a more fundamental level of

competition, and his successes in these contests were an important part of the process by

which he achieved immortality. This process reveals the important relationship between

athletic contests and heroic adventures. In addition to his sportive athletic endeavors,

Herakles and his adventures represented a broader conception of athleticism, based on

ancient Greek notions of contests, labors, and prizes. Underscoring this close relationship, ancient Greek literary sources often used athletic terminology to describe Herakles

exploits.17 Isocrates, a fourth-century B.C. Athenian rhetorician, described Herakles life

as full of agones or contestsprecisely the same terminology used to denote athletic competitions. Many ancient writers called the best known of Herakles adventures, the socalled twelve labors, athla, the root of the English word athlete. This word denoted

competitive struggle but literally referred to prizes or the contests for prizes. The athla or

labors of Herakles characterized him as an athlete who struggled for his prizein

this case, the prize of immortality. Thus, Herakles the athlete strove to complete his

labors, such as killing the Nemean lion, cleaning the stables of Augeas, and fetching the

apples of the Hesperides.18

Ancient writers often connected the immortality of Herakles with the completion of

his labors. The poet Hesiod noted that Herakles ascended to Olympus once he had

completed his wretched labors. The ancient poets and writers Pindar, Apollonius of Rhodes,

Diodorus Siculus, and Apollodorus all made a similar assertion, that Herakles achieved

Fall 2009

379

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

immortality by means of the completion of a series of designated tasks and contests.19

Consequently, mortal athletes in ancient Greece who completed their own athla, or labors, could lay claim to heroic honors.

There seems to have been a considerable number of mortals who achieved some type

of heroic status in ancient Greece. Although mortal imitation of heroic figures was not

limited to athletic figures, victory in athletic contests provided one avenue to heroic status.

With respect to the majority of athletic champions who received some type of heroic

status after death, few details have survived. Most attestations are passing or fragmentary

references. Moreover, many of the sources for these athletes are much later in date, making precise dating of the beginnings of heroic cult problematic. Nevertheless, there exists

sufficient literary, epigraphic, and archaeological evidence to place some of these cults in

the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., suggesting that the attainment of heroic immortality

through athletic victories was indeed a viable goal for prominent ancient Greek athletes of

the sixth, fifth, and fourth centuries B.C.20

The fifth-century B.C. historian Herodotus related that the people of Egesta on the

island of Sicily honored a colonist named Philippos as a hero. This colonist was an Olympic champion, but Herodotus explained that Philippos was heroized because he was extraordinarily good looking.21 According to an ancient commentator on the Hellenistic

poet Callimachus, the statue of an Olympic victor named Euthycles was worshiped at

Locri equally to the statue of Zeus. A much later source added that the people of Locri

wrongfully imprisoned the pentathlete and disgraced his statues after he died. This unjust

behavior sparked a crippling famine, and the people of Locri instituted a cult for Euthycles

in order to save their city. 22 Even the second-century writer Pausanias was confused by

the conflicting dates for the runner Oibotas of Dyme. Supposedly, Oibotas won at the

Olympic games during the eighth century B.C., yet some sources claimed that he had

fought against the Persians at the Battle of Plataea in 479 B.C. At any rate, the people of

Dyme later remembered the athlete with sacrifices and garlands.23 The ancient Spartans

worshipped Hipposthenes, a wrestler who won six Olympic crowns in the seventh century

B.C., in conjunction with the god Poseidon.24 In addition to these examples, modern

scholars have suggested other prominent and successful athletes who probably merited

heroic commemoration due to their athletic victories but have no association with heroic

cult in the surviving sources.25 These poorly attested examples do little more than demonstrate that the ancient Greeks heroized their athletes on occasion, but more substantive

accounts are necessary to identify and analyze any impulses by athletes to imitate heroic

actions. Fortunately, a few such accounts have survived. The earliest of these athletic

imitators of the mythic heroes was Milo of Croton.

In the late sixth century B.C. Milo, one of the greatest athletes of ancient Greece, won

six Olympic crowns in wrestling, a remarkable feat. Convinced of his own power and in

imitation of Herakles, Milo led the soldiers of Croton, a Greek city in Italy, in a battle

against the neighboring community of Sybaris while crowned with his six Olympic wreaths,

wearing a lion skin, and carrying a club. The olive wreaths, the lion skins, and the club all

featured prominently in the myths concerning Herakles. Representing himself as Herakles,

Milo led his countrymen to victory. The ancient historian Diodorus reported that the

people marveled that Milo was personally the cause of Crotons victory.26 Thus Milo, a

remarkable and victorious athlete, sought to imitate the military might of the mythic

380

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Herakles. His athletic successes had endowed him with what he considered to be supernatural power, and he used this power to win military victory for his city and heroic status

for himself.

Nearly two hundred years later, during the fourth-century B.C. campaigns of Alexander

of Macedon, an Athenian athlete named Dioxippos defeated a fully armed Macedonian

soldier in single combat. The Macedonian, named Koragos, must have had a little too

much to drink at the raucous banquet where he challenged Dioxippos, a renowned athlete

and a boxing champion in one of the Crown Games.27 On the day of the duel, Koragos

arrived decked out in fine armor and weapons. Dioxippos, on the other hand, came

naked, his body oiled, wearing a garland, and carrying only a club. Appearing as a victorious athlete and armed as Herakles, Dioxippos easily defeated the well-armed Macedonian.

The Olympic champion relied on his athleticism, avoiding Koragos javelin throw, shattering his lance with a blow from the club, and wrestling him to the ground as the

Macedonian reached for his sword. In accordance with the myths surrounding Herakles

and his manifold duels and contests, Dioxippos treated this encounter as a contest in

which he, the Heraklean athlete, vanquished the better armed (and not entirely Greek)

enemy.28 Clearly, Milo and Dioxippos considered themselves imitators of and successors

to the mythic Herakles.

Both Milo and Dioxippos imitated Herakles in battle and in sport. Both wore crowns

that proclaimed their athletic victories, and Dioxippos competed in the nude as an athlete.

Applying Plutarchs three-fold formula for divinity, both demonstrated might and arete

through their athletic and military successes, in direct imitation of Herakles. The sources,

however, are silent as to whether Milo ever received any measure of cultic worship after his

death. Modern scholars certainly consider him a candidate for such honors.29 Dioxippos,

however, received no such honors: he later committed suicide after being framed for theft.30

The story of Polydamas of Skotoussa, however, provides an example of a successful athlete

who imitated Herakles and who received religious cult after his death.

Polydamas, a pankratiast, won a crown at the Olympic games of 408 B.C. His exploits, surely exaggerated, reportedly included pulling the hoof from a struggling bull and

stopping a moving chariot by grabbing on and digging his heels into the ground. Furthermore, in some sort of agonistic duel, he simultaneously fought and defeated three members of the elite bodyguard of the Persian King in the court of Darius II. Without exaggerating the connections to mythic precedent, this one-against-three battle certainly evokes

echoes of Herakles combat with the triple-bodied Geryon. Both the Persians and the

monstrous Geryon represented fantastic, non-Greek forces, and the triplicate enemy suggests a convenient parallel.

Besides this thematic similarity, Polydamas openly imitated the great Herakles in other

endeavors. As Pausanias reported, out of an expressed desire to emulate the mythic hero,

Polydamas went to Mount Olympus and killed a large lion with his bare hands. A surviving portion of Polydamas fourth-century B.C. statue base at Olympia shows the great

athlete fighting a lion, linking this story more closely to the athletes lifetime.31 These

heroic actions brought Polydamas some type of heroic status among the Greeks since, after

his death, his statue was said to heal the sick.32 Polydamas athletic and heroic might and

arete afforded his memory a degree of supernatural or superhuman power. Like his model

Herakles, Polydamas achieved a measure of immortality and continued to exert influence

Fall 2009

381

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

on earth after his death, at least in the minds of the ancient Greeks. These examples

demonstrate the strong impetus of ancient Greek athletes to imitate Herakles. As these

athletes challenged the boundaries between the mortal and immortal realms, they became

more associated with the heroic tradition. In addition to the imitations of Milo and

Dioxippos, and the supernatural powers attributed to the statue of Polydamas, three athletes from the early fifth century B.C.Euthymos, Theagenes, and Kleomedesmade

the transition, in Greek minds, from athlete to hero.33

Euthymos of Locri, in Italy, was the Olympic boxing champion in 484, 476, and 472

B.C. In imitation of Herakles, Euthymoss adventures associated him with supernatural

events, indicative of his super-mortal status. According to the story, Euthymos fought a

demon called the Hero at Temesa, Italy. The Hero was supposed to be the ghost of

Polites, one of Odysseus comrades who had been stoned to death after raping a local girl.

The sailors ghost continued to torment the people of Temesa, requiring a virgin sacrifice

each year. By chance, Euthymos happened along as the townspeople were shutting that

years unfortunate girl into the ghosts precinct. The great athlete entered the temple,

fought the spirit, and drove it under the sea.34 Very similar in action and theme to the

story of Herakles and Hesione at Troy, Euthymos the neo-hero defeated the monster and

rescued the girl.35 Accordingly, Euthymos accumulated other vestiges of ancient Greek

heroism as exemplified by Herakles, principally a supernatural genealogy and an escape

from the finality of death. Euthymos did not die as ordinary mortals perish. Instead, he

disappeared into the river Caecinus, which was supposedly his father.36

As in the other examples, this athlete, through his Heraklean escapades, acquired

heroic status, perhaps in his own lifetime. The fifth-century B.C. inscription on the

pedestal of Euthymos victory statue at Olympia informs the reader that Euthymos himself set up the statue for mortals to behold.37 The Roman Pliny, citing the Hellenistic poet

Callimachus, claimed that after lightning struck the statues of Euthymos at Olympia and

at Western Locri on the same day, the oracle of Delphi gave instructions for the still-living

Euthymos to be deified.38 At Locri, archaeologists have discovered five herms dedicated

to the great athlete. The image on the herms depicts a bull with the head of a man, and the

inscriptions indicate that this represented Euthymos. Epigraphists have dated these inscriptions to the late fourth century B.C. Bruno Currie concluded that the image of a

man-headed bull on the herms represented an actual free-standing statue, perhaps in

bronze, which stood somewhere in the region and declared itself sacred to Euthymos.39

Thus the people of Locri heroized Euthymos, a remarkable athlete, for his heroic achievements. These heroic honors, sparked by the lightning strikes, dated to Euthymos own

lifetime, according to Pliny, and lasted at least into the next century.

Theagenes of Thasos, a contemporary of Euthymos who competed against him, was

another heavy-event athlete who achieved heroic status. An accomplished boxer and

pankratiast, Theagenes won both events at the same Olympic games in the early fifth

century B.C., in addition to nine Nemean and ten Isthmian championships. Like Polydamas

and Euthymos, the stories of Theagenes life have accumulated a good deal of mythic

exaggeration. For instance, the epigram that adorned his statue reportedly claimed that

Theagenes once ate an entire ox, and as a boy he is supposed to have carried a large bronze

statue he admired home from the citys marketplace. Like the other athletic would-be

heroes, Theagenes is reported to have consciously sought association with his mythic pre382

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

decessors. Out of ambitious envy of Achilles, reputedly the swiftest of the Greek heroes,

he abandoned combat sports for running and won a long-distance race in the hometown

of Achilles.40 Other sources asserted that the Thasians associated their athletic champion

with Herakles, claiming that Theagenes was really the son of the immortal hero instead of

the mortal man who raised him, although his victory inscriptions listed Timoxenos as his

father. After Theagenes death, one of his enemies went to the athletes statue every night

and flogged it out of hatred for the dead man. When, one night, the statue fell on the

enemy and killed him, the mans sons prosecuted the statue for murder and the people of

Thasos threw it into the sea. Later, in order to dispel a famine, the Thasians fished up the

statue, re-dedicated it, and offered sacrifices to it as a divinity. Jean Pouilloux, one of the

excavators of Theagenes shrine, suggested that the statues trial took place in the fifth

century B.C., between 440 and 420, within a generation or so of Theagenes athletic

victories in the early to mid fifth century. In addition, Pausanias claimed to know of

statues of Theagenes in many other locations that possessed the ability to cure diseases.41

Theagenes impressive exploits as an athlete and a heroic imitator brought his memory

divine recognition and heroic status after his death. As with Euthymos, part of Theagenes

heroization came from his revised ancestry and his direct imitation of the heroes, in this

case both Herakles and Achilles.

In 1939, French archaeologists unearthed a small stone treasury or deposit-box for

offerings to Theagenes in the foundations of the heros shrine in the ancient agora on

Thasos.42 Seventy-three centimeters in height, the cylinder displayed two inscriptions,

dated by its stratigraphic location and epigraphic features to the end of the first century

B.C. The earlier of these inscriptions regulated monetary offerings to the heroic athlete.

It required those coming to sacrifice to Theagenes to make a small offering by inserting an

obol coin through the opening in the top of the stone treasury. The second inscription,

somewhat fragmentary, much briefer, and inscribed later, probably during the first century A.D., promised good fortune to the donor and the donors family. In addition,

archaeologists have uncovered inscriptions that list Theagenes many panhellenic victories

in his hero shrine at Thasos, and copies have also been found at Delphi and Olympia. The

opening lines of the version from Delphi, the most complete of the three, highlights the

separation between the mighty Theagenes and ordinary mortals:

You, son of Timoxenos [. . .]

For never at Olympia has the same man been crowned

for victory in boxing and in pankration.

But you, of your three victories in the Pythian Games, won one unopposed,

a feat which no other mortal man has accomplished.

In nine Isthmian Games, you won ten times. For twice

the herald proclaimed your victories to the ring of mortal onlookers

in boxing and pankration on the very same day.

Nine times, Theogenes [sic], you won at the Nemean Games.

And you won thirteen hundred victories in the lesser contests.

Nobody, I declare, defeated you in boxing for twenty-two years.

Theagenes, son of Timoxenos, from Thasos, won these events:

[Thereafter follows a list of Theagenes Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean victories, as well as a victory in the long-distance dolichos footrace at Argos.] 43

Fall 2009

383

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

Like the inscription of Euthymos, this monumental commemoration both proclaims

the achievements of the great Theagenes while also distinguishing him from other mortals. The fifth surviving line reminds the reader (listener) that Theagenes accomplished

victories that no other mortal has ever managed. Furthermore, the herald proclaims

Theagenes victories to a crowd of mortals, as the Greek word (epichthonin) literally

means those on earth, and again draws a sharp distinction between the awe-struck onlookers and the mighty victorious athlete. The heroization of Theagenes, made possible

through his manifold victories, elevated him above the status of those on earth.

Although Theagenes won his victories in the early fifth century B.C., c.490-470, the

cultic veneration of the accomplished athlete seems to date to about a hundred years later

in the early fourth century B.C. The inscriptions from Delphi and Thasos, as well as the

statue base in the citys agora have all been assigned to this time, but the murderous statue

presumably dated to Theagenes own lifetime.44 The institution of an elaborate cult in the

citys center for the great athlete within a century of his death, most likely a space of only

two or three generations, demonstrates the significance of Theagenes victories. His memory

remained powerful enough to merit an expanded cult in the Hellenistic and Roman periods that lasted for hundreds of years. His great victories, including his imitation of the

hero Achilles, brought him heroic honors on Thasos and in many other places among

both Greeks and barbarians.45 These athletes, following the heroic paradigm of athletic

excellence, demonstrated through victory, achieved heroic honors in their own right. The

puzzling case of Kleomedes, however, represents a departure from this model in some

respects.

One of the most perplexing examples of the athlete-hero is the boxer Kleomedes of

Astypalaea, most notorious for his manically violent behavior. An Olympic boxer,

Kleomedes defeated his opponent in 492 B.C., Ikkos of Epidauros, by beating him to

death. The Olympic judges, however, disqualified Kleomedes for his excessive brutality.46

Stripped of his victory, he returned to Astypalaea where he pulled a supporting pillar from

a school, causing the roof to collapse and kill sixty boys. Fleeing the angry townspeople,

Kleomedes hid inside a chest in the sanctuary of Athena. When pursuers broke the chest

open, Kleomedes had disappeared. An inquiry to the Delphic oracle elicited a response

that the people of Astypalaea should worship Kleomedes as the last of the heroes.47

While his disqualification at Olympia was considered the cause of his madness, Kleomedes

nevertheless did not quite fit precisely into the model of athletic champions seeking heroic

status. His actions, killing young boys, hardly compare with the feats of Polydamas or

Euthymos, despite the folkloric elements of the collapsing roof.48 The stories of Herakles,

however, do provide a parallel example. The myths relate that the goddess Hera caused a

fit of insanity to come upon Herakles, causing him to kill his own children.49 In addition,

the myths claim that Herakles murdered his lyre teacher, Linos, for hitting him during a

music lesson, and he treacherously killed Iphitus, who was searching for his lost mares.50

Clearly, some of the stories concerning Herakles contained irrational, manic, and murderous violence. Perhaps the people of Astypalaea connected Kleomedes manic violence

with the insanity of Herakles. A connection to the immortal Herakles would help explain

an otherwise confusing sequence of events that led to Kleomedes heroization by the people

of Astypalaea.

384

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Kurke has proposed that the people of Astypalaea heroized Kleomedes because he did

not receive his deserved attention or acknowledgment for the kudos he acquired at Olympia.51 With the suspension of the normal ritual for reintegrating a kudos-charged individual into the community, Kleomedes wrathful power punished the citys residents. The

institution of a heroic cult allowed the city to tame and participate in the athletes power.

While Kurkes argument is persuasive, a comparison of Kleomedes to Herakles adds to this

explanation for the heroization of Kleomedes by providing a paradigm for understanding

the potential violence of a dangerous hero.

These anecdotal examples indicate the dynamics of heroizing successful human athletes from the late sixth, fifth, and fourth centuries B.C. While the sources suggest that

these athletes on occasion imitated the exploits and achievements of the mythic heroes,

the willingness of the community, often encouraged by a pronouncement from the Delphic oracle, played a key role in the awarding of heroic honors. Nevertheless, in addition

to the communitys role, the active striving for heroic honors during an athletes lifetime, a

phenomenon which Bruno Currie called the subjective aspect of hero cult, allowed a

historical athlete who successfully completed contests, duels, and challenges to claim the

ultimate prize of heroic immortality.52 The athletes efforts, however, provided only part

of the formula for heroization. For the ancient Greeks, heroic immortality consisted of

two components, glory and fame (kleos) and cultic honors (tim).53 The most important

feature was to be remembered in some way after death, either by reputation or through

religious ritual. The posthumous heroic honors afforded to victorious athletes implied

more than simple commemoration, however. Ancient Greek religion required sacrifice

and ritual to appease and supplicate supernatural forces for some measure of earthly benefit.54 The living honored the heroes because they continued to exert influence on earth.

The ancient Greeks remembered and commemorated the deceased heroes with the understanding that they would employ their supernatural powers on the suppliants behalf.

Thus, the Thasians retrieved the statue of Theagenes to end a famine, the statue of Polydamas

healed the sick, and the Achaians sacrificed to Oibotas to dispel his curse that had prevented them from winning Olympic victories. Although a mortal athlete could personally

do little to guarantee the observation of rites after his death, a victorious athlete could, in

accordance with heroic models, seek to amass fame and receive honors in his own lifetime.

The quest for kleos (fame and glory) is an important component of heroic immortality. Most likely, the world kleos is etymologically related to the ancient Greek word that

meant to hear. Thus, kleos depended upon a listening audience that would add to the

victors fame.55 The commemoration of athletic victors in verse represented an important

component of an athletes kleos and helped connect mortal athletes with the mythic heroes. The public performance of victory, or epinikian odes proclaimed the kleos of the

victors, and elevated their status in the minds of the audience. Even the inscriptions that

adorned a victors statue provided a means of continual kleos long after the victor had

departed. Many of these inscriptions were composed in order to re-enact and retell the key

elements of the victors experience, such as name, patronymic, homeland, and event. An

interested tourist who read the inscription aloud would, in effect, imitate the herald who

had originally announced the victory.56 Thus, the erection of a statue with an inscription

provided a vehicle for nearly perpetual kleos, as long as those who passed by stopped to

Fall 2009

385

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

look at the statue and read the inscription. In addition to the inscriptions that adorned

their statues many important victors enjoyed commemoration in verse.

Hellanicus of Lesbos, for instance, a historian and mythographer from the fifth century B.C., recorded a list of victors in Spartas Karneian festival in both poetry and prose.57

Although no fragments of Hellanicus Karneonikai have survived, ancient testimonies clearly

stated that Hellanicus used metered verse to record the victors names. In many respects,

the use of poetic meter represented the language of the gods. The Greeks delivered divine

communications, such as pronouncements from the Delphic oracle, in dactylic hexameter. According to Plato, the Muses spoke to poets in verse, and the poets acted merely as

vehicles for conveying the divine words.58 Thus, when Hellanicus recited his metrical list

of Karneian victors, he would have evoked images in his audience of divine communications and the heroic age. The effect must have been akin to the second book of the Iliad,

where Homers catalog of ships names and describes the epic poems Greek heroes and

their homelands. In compiling a list of historical athletic victors and arranging them into

verse, Hellanicus implicitly connected these men and their achievements with the immortal Homeric heroes.

In addition to Hellanicus list, the performance of epinikian praise poetry in honor of

the victors at prestigious athletic contests added heroic kleos to the athletes reputations.

Pindar, a poet who lived during the late sixth and early fifth centuries B.C. is the best

known of the epinikian poets. In his poetry Pindar alluded to the propensity for powerful

and successful mortal athletes to seek a status above regular humans, often juxtaposing the

feats of a victorious mortal athlete with the achievements of a mythic hero.59 For example,

Pindars First Olympian Ode, composed to commemorate the Sicilian tyrant Hieros victory in a chariot race at Olympia in 476 B.C., described the story of a chariot race from

mythic time. Here, Pindar re-tells a well-known story about the hero Pelops, who won a

dramatic chariot-racing victory over the ruthless Lord of Pisa and came away with his life,

a bride, and a kingdom. Fittingly, the Greeks honored Pelops at Olympia with a shrine

and sacrifices in the sacred Altis.60 By juxtaposing the victory of Pelops with the victory of

Hiero, Pindars Ode connects the mortal realm with the immortal, and Pindars poetry

provides several additional examples of this phenomenon.61 Pindar was well aware of the

ambiguous status of the mortal athletic champion. Despite his close associations of mortal champions with mythic heroes, the poet on numerous occasions reminded his patrons

and listeners that a victors status among the heroes, while greater than any mortal, was still

less than the status of the gods.62 Thus Pindar recognized the special status of both the

heroes and his victorious subjects, while cautioning them against hubristically claiming to

be equal to the gods.

Yet another commemoration in verse equated victorious athletes with the immortal

heroes. Victorious Olympic champions enjoyed identification with Herakles by means of

a victory song, or kallinikos. Those accompanying or welcoming an Olympic victor sang

this hymn to Herakles in honor of the victorious athlete.63 Originally composed by the

poet Archilochus in the seventh century B.C., only a small fragment has survived in the

opening lines of Pindars Olympian 9 and the explanatory note of an ancient commentator. The hymns repeated refrain proclaimed, Hail glorious victor! Greetings lord

Herakles!64 This hymn to Herakles, performed in honor of the victorious athlete, connected the mortal victor to the immortal hero. Although ostensibly addressed to Herakles,

386

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Detail of an ancient Greek krater bowl (c.360 B.C.). In the image,

Herakles (far right), clothed in the skin of the Nemean lion and carrying his club, admires his victory statue as a worker applies paint. Winged

Victory (Nik) hovers above. Victorious athletes often erected statues

in sacred precincts, such as Olympia or Delphi, in honor of the gods

and in commemoration of their accomplishments. A victory statue

provided a vehicle for nearly perpetual kleos. This scene stresses the

importance of victory in Herakles athletic endeavors and underscores the connections between the honors paid to athletes and heroes

in ancient Greece. COURTESY OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART,

ROGERS FUND, 1950 (50.11.4). IMAGE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF

ART. REPRODUCTION OF ANY KIND IS PROHIBITED WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN

PERMISSION IN ADVANCE FROM THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART.

the context of the hymns performance allowed the victorious athlete to appropriate this

praise for himself. By implicitly calling the athlete Herakles, the singer connected the

athletes accomplishment with those of the hero. Like Herakles, the mortal athlete could

lay claim to super-mortal status. Like Herakles, these mortal athletes aspired to the prize

of immortality.

Fall 2009

387

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

The potential prize of immortality through heroic cult was an appealing quest for

prominent athletes in ancient Greece. While athletic prowess, both in sporting and more

thematic struggles or contests comprised an important part of heroic identity, those

humans who achieved great victory in sporting contexts sought to extend their fame and

glory by connecting themselves to the mythic heroes. Like Herakles, who successfully

overcame all obstacles and completed his labors or athla, victorious athletes sought their

own heroic adventures in their quests for immortal status and heroic honors after death.

Charged with kudos and hungry for kleos, these powerful champions claimed a heroic,

superhuman status that enabled them to lead their cities to victory in battle or to continue

to exert influence over earthly affairs after their deaths. In addition to heroic imitation,

successful athletes enjoyed associations with immortal heroes through verse, as the poets

extolled and commemorated the victors in the same fashion as the great heroes of Homer.

The power, might, and arete of their athletic victories provided the justification for their

heroization.

The connections between the mythic heroes and historical athletes from the sixth,

fifth, and fourth centuries B.C. provide a considerable amount of information for evaluating the role of the heroes in both ancient Greek athletics and religion. While the athletes

community played an important part in awarding, reviving, or augmenting heroic cult for

a notable athlete, the process of heroization surely varied over time and place in the ancient Greek world. Nevertheless, the sources suggest that, in some cases, great athletes

sought to imitate the heroes of myth, intending to secure for themselves the same degree

of glory and recognition. While many of the literary sources date from the Roman period,

epigraphic and archaeological evidence, such as the statue base of Polydamas and the cults

to Euthymos and Theagenes, fixes heroic imitation and the institution of heroic honors

much closer to the athletes lifetimes. In addition, Pindars admonitions and comparisons,

composed in the late sixth and early fifth centuries B.C., suggest a tendency for powerful

and successful athletes to seek superhuman status at this time. Pindar warned such victors

to avoid the hubris of claiming the status and power of the gods but allowed for humans to

achieve heroic status. After all, the heroes of myth had been humans themselves who had

managed to secure commemoration and cult, as well as continued influence on earth. For

prominent athletic champions from the sixth, fifth, and fourth centuries B.C., athletic

achievements provided access to the same honors.

Plutarch, Life of Aristides 6: fqarsa ka dunmei ka ret.

Hesiod, Works and Days 159-160: ndrn rwn qeon gnoj, o kalontai, mqeoi.

3

Plut., Life of Theseus 6.

4

Paul Veyne, Did the Greeks Believe in Their Myths?, trans. Paula Wissing (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1988), 42.

5

Joseph Fontenrose, The Hero as Athlete, California Studies in Classical Antiquity (later Classical

Antiquity) 1 (1968): 87-88.

6

Leslie Kurke, The Economy of Kudos, in Cultural Poetics in Archaic Greece, eds. Carol Dougherty

and Leslie Kurke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 149. Franois Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes

en Grce Classique, Rvue des tudes Anciennes 81 (1979): 9 commends Fontenroses beau schema but

found it quasiment dpourvu de signification.

1

2

388

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 5-18.

Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 14, for instance, notes that Milo of Croton

inaugurated a time of great prestige and prosperity for his city and subsequently received no cultic honors.

9

Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 11 suggests that Theagenes of Thasos intervened directly in a reformation of the citys rites to Herakles in order to claim descent from the great hero.

Euthymos and Theagenes seem to have received cultic honors as early as the fourth century B.C. (Bohringer,

Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 15).

10

Bohringers treatment of Milo of Croton, for instance, glosses over the similarities between the life

and adventures of the great wrestler and Herakles, since Milo received no posthumous cult. (Bohringer,

Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 14).

11

Bruno Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 120-157.

12

Kurke, The Economy of Kudos, 132. However, cf. Poulheria Kyriakou, Epidoxon Kydos:

Crown Victory and Its Rewards, Classica et Mediaevalia 58 (2007): 119-158. Kyriakou challenges this

narrow definition of kudos, citing usage in Homer, Pindar, and Bacchylides. Despite Kyriakous dismissal

of any type of athletic talismanic power or magic, her assertion that victory in the Crown Games was

lucrative only because of its political potential as a display of skill and affluence in a truly Panhellenic

venue dismisses the deeply ritualistic nature of victory in the sacred games (p. 149).

13

Spartan kings, for instance, were accompanied in battle by victors in the crown games. (Plut. Life

of Lycurgus 22; Quaestiones Convivales 2.5.2). Plutarch cites Duris of Samos in relating a story that

Alcibiades returned in triumph to Athens accompanied by a Pythian champion flute player. Plutarch,

however, notes that the extravagant details in Duris are absent from the accounts of Theopompus, Ephorus,

and Xenophon, and seems inclined to disbelieve the story (Plut. Life of Alcibiades 32). Kurke, The

Economy of Kudos, 133-137, suggests that colonist leaders (called oikists), such as Miltiades, the son

of Cypselus who led colonists to the Chersonese, were chosen because of their victories in the crown

games. After his death, the people of the Chersonese instituted games in Miltiades honor, including

chariot-racing and gymnastic competitions (Herodotus 6.36-38). This Miltiades was the uncle and

namesake of the general who led the Athenians to victory at Marathon in 490 B.C. However, cf. Kyriakou,

Epidoxon Kydos, 144-145, who downplays the connection.

14

Mark Golden, Sport and Society in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998),

146-157, associates the Herakles myths with sport through the lens of aristocracy and wage labor. Ultimately, Golden concludes that Herakles and the ancient Greek aristocratic ideal of sport proved superior

to the undertaking of menial tasks for money.

15

Pindar, Olympian 3.20-25; 6.67-70; Diodorus Siculus 4.14.1, 5.64.6; Pausanias 5.7.9, 5.8.3. A

single (late) source claims that Herakles himself won Olympic victories in wrestling and pankration

(Paus. 5.8.4).

16

According to Apollodorus, Herakles killed Polygonus and Telegonus, both grandsons of Poseidon,

in a wrestling match (Bibliotheca 2.5.9). When the Sicilian hero Eryx challenged Herakles to a wrestling

bout for one of Geryons cattle that had escaped and joined his herd, Herakles killed him on his third

throw (Apollod, Bibl. 2.5.10; Paus. 3.16.4-5; Diod. Sic. 4.23.2). When Herakles came across Antaeus, a

son of Poseidon who killed strangers by wrestling them to death, the great hero killed him in a wrestling

match by preventing Antaeus from touching the ground, from which he drew his strength (Apollod.

Bibl. 2.5.11; Pind., Isthmian 4.52-55). Herakles even wrestled in the underworld, breaking the ribs of

Menoetes, who tended Hades cattle and objected to Herakles slaughter of one to provide blood for the

shades of the dead. (Apollod. Bibl. 2.5.12.).

17

For example, Homer, Iliad 8.362; Odyssey 11.622; Hes., Theogony 951; and Acusilaus, fragment

29 (Fowler). Diod. Sic. 4.11.3 uses qla exclusively to refer to the works done for Eurystheus. Apollod.

Bibl. 2.4.12; Paus. 8.18.3. Pind. Nemean 1.70 is an exception, referring to Herakles labors as great toils

[kamtwn meglwn].

18

Isocrates, Helen 17: Herakles glory came from wars and contests; Golden, 150 for athla and

athlete. The canon of twelve labors for Herakles does not seem to have been fixed until the mid fifth

7

8

Fall 2009

389

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

century B.C., when the metopes depicting the heros feats were carved for the great temple of Zeus at

Olympia. Although there is some variation in early accounts of Herakles labors, the temples metopes

indicated that the other nine labors were killing the Lernaean Hydra, fetching the Kerynitian Deer,

capturing the Erymanthian Boar, driving off (or killing) the Stymphalian Birds, capturing the Cretan

Bull, stealing Diomedes Horses, bringing back the belt of the Amazon queen, obtaining Geryons Cattle,

finding and acquiring the apples of the Hesperides, and bringing the many-headed Kerberos up from the

underworld. See Timothy Gantz, Early Greek Myth (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1993), 381-416, for general discussion of the labors. See Wendy J. Raschke, Images of Victory in The

Archaeology of the Olympics, ed. Wendy J. Raschke (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 4245, for a brief discussion of Herakles, his labors, the metopes, and immortality in an agonistic context.

19

Hes. Theog. 951: telsaj stonentaj qlouj. Pind. Nem. 1.70 describes Herakles rest on Olympus

as his reward for his great toils. Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 1.1318-1319; Diod. Sic. 4.8.1 and

4.10.7; Apollod, Bibl. 2.4.12. See also Theocritus 24.82-83, who calls the labors ddek . . . mcqouj.

Compare the myth of Psyche, the mortal woman who falls in love with the immortal Cupid as told in

Apuleius, Metamorphoses 4.286.24. Venus (Aphrodite), Cupids difficult mother, lays out many seemingly impossible domestic tasks for her sons would-be bride. After completing them through miraculous

means, Venus offers the girl a cup of ambrosia to make her immortal.

20

The Spartan king Agesilaus imitation of Agamemnon is one example of non-athletic heroic imitation. Xenophon, Hellenica 3.4.3-4; Plut., Life of Agesilaus 6, 9. See Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes,

120-123, for a complete list of the heroized athletes.

21

Hdt. 5.47.

22

Diegesis (ii.5) to Callimachus, Aeita 3.84-85 (Pfeiffer); Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica 5.34.

23

Paus. 6.3.8; 7.17.6. Concerning this story, Pausanias mused, I am bound to tell the stories that

are told by the Greeks, but I am not bound to believe them all.

24

Paus. 3.13.9; 3.15.7. Stephen Hodkinson, An Agonistic Culture? Athletic Competition in Archaic and Classical Spartan Society in Sparta: New Perspectives, eds. Stephen Hodkinson and Anton

Powell (London: Duckworth, 1999), 165-167, argues for a fifth-century B.C. institution of cult for

Hipposthenes and follows Bohringer in suggesting a connection between the heroization and natural

disaster and civil unrest at Sparta.

25

See Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, 120-123, for these athletes and their circumstances.

26

Diod. Sic. 12.9.5-6 (ation); Paus. 6.14.5-9; Strabo 6.1.12. Cf. Nikostratus Heraklean equipment in battle: Diod. Sic. 16.44.3.

27

Diod. Sic. 17.100-101; Quintus Curtius Rufus 9.7.16-26. Diodorus compares the combat to a

contest between Ares (Koragos) and Herakles (Dioxippos).

28

Hesiods Shield, however, describes Herakles arming himself as a hoplite soldier to fight Kyknos.

Nevertheless, Herakles in art was overwhelmingly portrayed without conventional military weaponry.

He fought with brute strength and his club. See also Pind. Ol. 10.15-16; Apollod., Bibl. 2.5.7, 11;

Hyginus, Fabula 31; Paus. 3.18.10; Euripides, Hercules Furens 389-393 for the duel between Herakles

and Kyknos.

29

Fontenrose, The Hero as Athlete, 88-89. See also Curries discussion, Pindar and the Cult of

Heroes, 155-157.

30

Diod. Sic. 17.100-101; Curtius 9.7.25. Curtius account of Dioxippos certainly presents the

wronged athlete as a tragic, heroic figure who perhaps imitates the mythic Ajax in preferring suicide over

disgrace. However, there is no indication of subsequent heroization.

31

Anna Maranti, Olympia & Olympic Games (Athens: Toubis, 1999), 102-103.

32

See Diod. Sic. 9.14.2; Paus. 6.5.1, 4-9 for Polydamas exploits; and Lucian, Parliament of the Gods

12 for the healing power of the statue.

33

For general discussion, see Fontenrose, The Hero as Athlete, 73-104; Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes

en Grce Classique, 5-18; Kurke, The Economy of Kudos, 149-152; and Currie, Pindar and the Cult

of Heroes, 120-124.

390

Volume 36, Number 3

LUNT: THE HEROIC ATHLETE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Paus. 6.6.4-10; Callimachus, Aetia fr. 98-99 (Pfeiffer); Pliny, Natural History 7.152; Aelian, Various Histories 8.18.

35

For Herakles, the sea monster, Hesione, and her father Laomedon, see Hom. Il. 5.628-51; Diod.

Sic. 4.42; Apollod. Bibl. 2.5.9; Hyginus, Fab. 89; Pind. Nemean 1.94-95; and Eur., H.F. 400-402. Bruno

Currie, Euthymos of Locri: A Case Study in Heroization in the Classical Period, Journal of Hellenic

Studies 122 (2002): 35-37, sees Euthymos as imitating Herakles fight with Achelos, a river deity.

36

Paus. 6.6.10; Aelian, Various Histories 8.18.

37

Equmoj Lokrj Astukloj trj Olmpinkwn sthsen tnde brotoj sorn; italics are authors.

Wilhelm Dittenberger, Die Inschriften von Olympia (Berlin: Asher, 1896) 144; Luigi Moretti, Inscrizioni

Agonistiche Greche (IAG) (Rome: Angelo Signorelli, 1953) 13; Joachim Ebert, Griechische Epigramme

Auf Sieger an Gymnischen Und Hippischen Agonen, Band 63, Heft 2, Schsische Akademie Der Wissenschaften

Zu Leipzig. Philologisch-Historische Klasse (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1972), 16; Stephen Miller, Arete:

Greek Sports from Ancient Sources, 3rd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004) 166b. Some

difficulties exist for understanding the dedication, since the stone shows evidence that the inscription was

modified in antiquity. In the Greek text, the portion that reads tnde brotoj sorn (for mortals to

behold) does not align with the line above, the poetic meter changes abruptly, and the characters are

recessed on the stone, making it quite clear that the original text was chiseled out and replaced with this

phrase. In addition, two more lines were added below this inscription, identifying Euthymos (in the

third person) as the dedicator and Pythagoras of Samos as the sculptor. Judging from letter forms, the

two parts of the inscription, including the revision to the first, are quite close in date, and both Joachim

Ebert and Luigi Moretti dated the inscription to c.470 B.C., shortly after Euthymos Olympic victories.

Moreover, Moretti is inclined to believe that Euthymos himself ordered the correction and the addition

after circumstances at Locri, perhaps such as the death of his father or financial difficulties in the city,

forced Euthymos to pay for the statue himself. Whatever the story behind the alteration and addition to

the dedicatory text, the fifth-century B.C. date of the inscription situates it in or close to Euthymos

lifetime.

38

Callim., Aet. fr. 99 (Pfeiffer); Pliny, Natural History 7.152. See Currie, Euthymos of Locri, 4044, for explanation and analysis of Euthymos cult at Locri.

39

Currie, Euthymos of Locri, 29-30. In ancient Greek art, a bull-headed man was a standard

representation of Achelos, a powerful river deity who fought against Heracles in myth. (see Gantz, 2829, 432-433). This artistic representation underscored the divinity of the powerful athlete by depicting

him as a river god, in this case likening him to Caecinus, his divine father.

40

Paus. 6.11.5: n d o prj Acilla mo doken t filotmhma.

41

Athenaeus 10.412 d-f; Dio Chrysostom 31.95-97; Lucian, Parliament of the Gods 12; Paus. 6.6.56, 6.11.2-9; Plutarch, Moralia 811d-e. Jean Pouilloux, Rcherches sur lHistoire et les Cultes de Thasos, 2

vols. (Paris: cole Franaise dAthnes, 1954), 1: 102-103, dated Theagenes and his cult according to

Thasos relationship with Persia, Athens, and Athenian law during the fifth century B.C., as demonstrated through the details of the statues trial. Bohringer, Cultes dAthltes en Grce Classique, 15,

found this date plausible. See Paus. 6.11.9 for the other statues of Theagenes.

42

R. Martin, Un Nouveau Rglement de Culte Thasien, Bulletin de Correspondence Hellnique 4445 (1940-1941): 163-200.

43

W. Dittenberger, Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum, 3rd ed. (Syll3) (Hildesheim, Ger.: Georg Olms,

1960), 36; Moretti, IAG 21; Desmond Schmidt, An Unusual Victory List from Keos: IG XII, 5, 608

and the Dating of Bakchylides, Journal of Hellenic Studies 119 (1999): 76-77; Elizabeth Pierce Blegen et

al., Archaeological News, American Journal of Archaeology 53 (1949): 368. See Pouilloux, Rcherches sur

lHistoire et les Cultes de Thasos, 78-82, for textual criticism.

44

Martin, Un Nouveau Rglement de Culte Thasien, 197; Franois Salviat, Le Monument de

Thogns sur lAgora de Thasos, Bulletin de Correspondence Hellnique 80 (1956): 159-160; Schmidt,

An Unusual Victory List from Keos, 76; Susan C. Jones, Statues That Kill and the Gods Who Love

Them in STEFANOS: Studies in Honor of Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, eds. Kim J. Hartswick and Mary

C. Sturgeon (Philadelphia: The University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania, 1998), 141. Jean

34

Fall 2009

391

JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY

Pouilloux, Thogns De Thasos . . . Quarante Ans Aprs, Bulletin de Correspondence Hellnique 118

(1994): 206, suggests a period of one or two centuries (un ou deux sicles) between Theagenes death and

the recognition of the athlete as a divine healer.

45

Paus. 6.11.9.

46

Paus. 6.9.6-8; Plut., Life of Romulus 28.

47

Paus. 6.9.8: statoj rwn Kleomdhj Astupalaiej.

48

Fontenrose, The Hero as Athlete, 88, points out that the collapsing roof was a common element

in folklore concerning powerful men. The death of the Biblical Samson, told in Judges 16, is one of the

best known of these stories.

49

Apollod., Bibl. 2.4.12.

50

Apollod., Bibl. 2.4.9, Paus. 9.29.3, Diod. Sic. 3.67.2 for Linos; Homer, Od. 21.22-30, Apollod.,

Bibl. 2.6.1-2 for Iphitus.

51

Kurke, The Economy of Kudos, 151-152.

52

Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, 7-9, 127.

53

Currie, Pindar and the Cult of Heroes, 72.

54

Walter Burkert, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 54.

55

Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991), 17.

56

Kurke, The Economy of Kudos, 142.

57

Literally, meter and catalog. Felix Jacoby, Die Fragmente der Griechischen Historiker (Berlin:

Weidmann, 1923), 4, fr. 886; Athenaeus 14.635e: j Ellnikoj store n te toj mmtroij Karneonkaij

kn toj katalogdhn.

58

Plato, Ion 534a-536d.

59

See Kurke, The Traffic in Praise, 163-194, for commentary on how Pindars odes contributed to a

victors symbolic and financial benefactions to his polis; Kurkes conclusion (257-262) details how the

epinikian poem negotiate[d] with the community to defuse the dangerous status the victors kudos had

brought and to facilitate his return to the community. Thus, Pindars poetry is intrinsically aware of the

superhuman status of athletic champions.

60

Pind., Ol. 1.90-96; Paus. 5.13.1-3; 6.22.1.

61

For example, Pind., Ol. 10, re-tells how Herakles founded the Olympic games and the mythic

athletes who won those initial events. Pyth. 10 associates the mortal victor Hippocleas with the hero

Perseus. Nem. 5 and Isth. 5 and 6 compare the brothers Pytheas and Phylakidas, two brothers from

Aegina, with Peleus and Ajax, two mythic brothers from the same island. Ol. 6 compares Hagesias of

Syracuse to the hero Amphiaraos.

62

Pind., Ol. 5.24; Isth. 5.14; Pyth. 3.61-62. Pindar also reminds his listeners that they are but mortals (Nem. 11.13-16) and that only the praise of bards survives mortal life (Pyth. 1.92-94). See also Mark

Munn, The Mother of the Gods (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 22-23, esp. n30. Nemean

6.1-5 emphasizes the separation between the races of gods and men but allows for humans to approach

the immortals. David Young, Something Like the Gods: A Pindaric Theme and the Myth of Nemean

10, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 34 (1993): 126-127, considers these phrases not serious warnings but highly complimentary statements.

63

Lillian Lawler, Orchesis Kallinikos, Transactions of the American Philological Association 79 (1948),

254-255.

64

Archilochus, fr. 324 (West): tnella kallnike care nax Hrkleij/atj te ka Ilaoj, acmht

do/tnella kallnike care nax Hrkleij; Scholiast to Pind., Ol. 9.1-3 (Teubner).

392

Volume 36, Number 3

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Republic by PlatoDocument569 pagesThe Republic by PlatoBooks94% (18)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Greek MythologyDocument48 pagesGreek MythologyMayank01071991100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Bulfinch MythologyDocument914 pagesBulfinch Mythologyapi-3782084100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Druid BibleDocument11 pagesDruid Biblecerebus20101156100% (1)

- The Odyssey by HomerDocument3 pagesThe Odyssey by HomerSaif Ramirez CarrionNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Aegean ArchitectureDocument27 pagesAegean Architecturenusantara knowledge50% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Puritan PoliticsDocument19 pagesPuritan PoliticsjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Centaurs LairDocument7 pagesCentaurs LairLiviu-George SaizescuNo ratings yet

- What Is MythDocument15 pagesWhat Is Mythtrivialpursuit100% (1)

- The Gypsy in The Poetry of Federico García LorcaDocument22 pagesThe Gypsy in The Poetry of Federico García LorcaDebora PanzarellaNo ratings yet

- Preboard English KeyDocument16 pagesPreboard English KeyGeraldine DensingNo ratings yet

- The Art of Being A (High School) StudentDocument31 pagesThe Art of Being A (High School) StudentjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- T e C Am C R, U D: Sue EusdenDocument14 pagesT e C Am C R, U D: Sue EusdenjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Pre-Hanging For Single Doors: All Choices Are Viewed From OutsideDocument1 pagePre-Hanging For Single Doors: All Choices Are Viewed From OutsidejbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Relationships That Work II (2011)Document5 pagesRelationships That Work II (2011)jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- LAPP passiveVoiceandItsDocument1 pageLAPP passiveVoiceandItsjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Basketry Designs of The Mission IndiansDocument30 pagesBasketry Designs of The Mission IndiansjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Society in Southern CaliforniaDRAFTDocument12 pagesAboriginal Society in Southern CaliforniaDRAFTjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Athrowofthedicetypographicallycorrect02 18 09 PDFDocument24 pagesAthrowofthedicetypographicallycorrect02 18 09 PDFRafael E Figueredo ONo ratings yet

- ESLA History Syllabus TemplateDocument1 pageESLA History Syllabus TemplatejbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Pre-Hanging For Single Doors: All Choices Are Viewed From OutsideDocument1 pagePre-Hanging For Single Doors: All Choices Are Viewed From OutsidejbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Mod RichardsdarwinDocument6 pagesMod RichardsdarwinjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Res Pub Tracker 2016Document7 pagesRes Pub Tracker 2016jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- ESLAHistory PoliciesSkillsBenchmarksDocument10 pagesESLAHistory PoliciesSkillsBenchmarksjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- University of California Press Pacific Historical ReviewDocument3 pagesUniversity of California Press Pacific Historical ReviewjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- City Lite - LatimesDocument2 pagesCity Lite - LatimesjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Class First Nalast Name GenderDocument12 pagesClass First Nalast Name GenderjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Citizens Outside GovernmentDocument30 pagesCitizens Outside GovernmentjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- 7th Aristotle SelectionsonthesoulDocument2 pages7th Aristotle SelectionsonthesouljbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- ColcommentarymachineDocument16 pagesColcommentarymachinejbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- LAPP Course Notes Summer 2016Document30 pagesLAPP Course Notes Summer 2016jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- The Admonitions of Ipuwer (Egyptian Papyrus, Middle Kingdom, Exact Date Unknown)Document1 pageThe Admonitions of Ipuwer (Egyptian Papyrus, Middle Kingdom, Exact Date Unknown)jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- 148686Document161 pages148686jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- APUSH JeopardyDocument1 pageAPUSH JeopardyjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- APUSH Assessment 3Document2 pagesAPUSH Assessment 3jbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- APUSH RevolutionDocument2 pagesAPUSH RevolutionjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Heroic Athlete in Ancient GreeceDocument18 pagesHeroic Athlete in Ancient Greecejbmcintosh100% (1)

- AP MasterDocument5 pagesAP MasterjbmcintoshNo ratings yet

- Epics FinalDocument3 pagesEpics FinalChris LeeNo ratings yet

- English I Mythology Summative AssessmentDocument4 pagesEnglish I Mythology Summative Assessmentapi-404093583100% (1)

- Ancient World, The OdysseyDocument6 pagesAncient World, The OdysseyAnastasia CamoctrokovaNo ratings yet

- Unutterable Horror - A History of Supernatural FictionDocument422 pagesUnutterable Horror - A History of Supernatural FictionHar IshNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Greek MythDocument5 pagesThesis Statement Greek Mythleanneuhlsterlingheights100% (2)

- Quiz results for CLAS 104 Online course on AthenaDocument4 pagesQuiz results for CLAS 104 Online course on Athenabrake saadNo ratings yet

- Greek MythologyDocument24 pagesGreek MythologyCelestra JanineNo ratings yet

- Cursed House of AtreusDocument18 pagesCursed House of AtreusJoana JoaquinNo ratings yet

- Roman Vs Greek MythologyDocument4 pagesRoman Vs Greek Mythologyapi-345225470No ratings yet

- Vernant, Semblances of PandoraDocument16 pagesVernant, Semblances of PandoraSteven MillerNo ratings yet

- HomerDocument4 pagesHomermaria cacaoNo ratings yet

- 2011DrawingCatalog PDFDocument64 pages2011DrawingCatalog PDFHarry SharmaNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1Document3 pagesSeminar 1Nana Smith100% (1)

- Ancient Greece InformationDocument19 pagesAncient Greece InformationsameelakabirNo ratings yet

- PSY130 Answer 6Document3 pagesPSY130 Answer 6Ralph Reubens ReyesNo ratings yet

- Helen's Hands: Weaving For Kleos in The Odyssey: Melissa MuellerDocument22 pagesHelen's Hands: Weaving For Kleos in The Odyssey: Melissa MuellerAriel AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Zeus Father Cronus and His SonDocument3 pagesZeus Father Cronus and His SonShawnLRatliffNo ratings yet

- Prelim NotesDocument8 pagesPrelim Notesrusseldabon24No ratings yet

- Sea DivinitiesDocument19 pagesSea Divinitiesdez umeranNo ratings yet

- Medusa and PursuesDocument2 pagesMedusa and Pursuesnosh Weissberg100% (1)

- Greek Heroine CultsDocument129 pagesGreek Heroine CultscelinnexxNo ratings yet