Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anatomical Distances of The Facial Nerve Branches

Uploaded by

sevattapillaiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anatomical Distances of The Facial Nerve Branches

Uploaded by

sevattapillaiCopyright:

Available Formats

Braz. J. morphol. Sci.

(2000) 17, 107 - 111

ANATOMICAL DISTANCES OF THE FACIAL NERVE BRANCHES

ASSOCIATED WITH THE TEMPOROMANDIBULAR

JOINT IN ADULT NEGROES AND CAUCASIANS

*Marcus Woltmann, Ricardo de Faveri and Emerson Alexandre Sgrott

Department of Anatomy, University of Vale do Itaja, Itaja, S.C., Brazil

ABSTRACT

In this study, we examined the relationship between the distances of the temporal and cervicofacial branches of the facial

nerve relative to the temporomandibular joint in 92 facial halves from 56 adult cadavers (37 Negroes, 19 Caucasians; 48 M, 8

F). Negro and Caucasian males frequently had a temporal branch more distant from the acustic meatus (1.59 cm) and the tragus

(2.09 cm) when compared to the respective females (1.25 cm and 1.82 cm). In mesocephalic Negro and Caucasian males, the

cervicofacial trunk frequently passed closer to the meatus (1.76 cm and 2.26 cm, respectively) than in brachycephalic Negro

males (2.30 cm) and in dolicocephalic Caucasian males (2.95 cm). Mesocephalic Caucasian males and brachycephalic Negro

males had larger distances for the cervicofacial branch (2.26 cm and 2.30 cm), respectively than the corresponding mesocephalic

(1.4 cm) and brachycephalic (1.8 cm) females. The location of the temporal branches and cervicofacial trunk of the facial nerve

increases the risk of lesions to these nerves during access to the temporamandibular joint. A knowledge of the measurements

obtained here may help to decrease the number of such lesions.

Key words: Facial nerve, temporal nerve, cervicofacial trunk, preauricular approach, temporomandibular joint

INTRODUCTION

A detailed knowledge of the topography of the facial

nerve and its temporal branches is fundamental for successful temporomandibular joint (TMJ) surgery since these

branches are susceptible to damage during this procedure [3].

A preauricular incision is frequently used to access the

TMJ, but can lead to a series of sequelae when incorrectly

performed, the most serious of which is paralysis caused by

injury to the facial nerve [6]. The risk of lesioning the facial

nerve in this type of incision is approximately 5% [7]. As a

result, the patient loses all facial expression on the affected

side and is unable to close the corresponding eye [2].

Al Kayat and Bramley [1] were the first to study the

facial nerve topography by measuring the course of its

branches and then correlating the measurements with the

site of the preauricular incision. There were no significant

variations in topography with age and gender.

In this work, we examined whether the high level of genetic miscegenation in Brazilians could affect the distances

of the temporal branches and cervicofacial trunk from the

temporomandibular joint. These values were compared to

Correspondence to: Marcus Woltmann - Departamento de Anatomia, Universidade do Vale do Itaja, R. Uruguai, 458, CEP 88302202, Itaja, S.C., Brasil. Tel: (55) (47) 341-7606, Fax: (55) (47) 3417601. E-mail: marcuswoltmann@zipmail.com.br

* Present address: R. Frederico Abrabches, 233 Apto. 92, Santa

Ceclia, CEP 01225-001, So Paulo, SP

those reported in the literature for more uniform populations.

We also investigated whether factors such as ethnic group,

sex and cephalic index could influence the distances obtained.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study sample consisted of 56 adult cadavers, (37 Negroes,

19 Caucasians) with a total of 48 males and 8 females, which corresponded to 112 facial halves. Twenty facial halves were discarded

because of their poor state of conservation. The remaining 92 facial

halves were dissected.

The cephalic index was obtained using the relationship

W x 100 / L , where W is the maximum cephalic width (cm), and L is

the maximum cephalic length (cm) [8]. The brachycephalic, mesocephalic and dolicocephalic indexes were < 74.9, 75 to 79.9 and > 80,

respectively.

The measurements were made with a special anthropometer which

consisted of a base with a ruler and four extremities, one of which was

immovable and had an active point fixed at 0 cm. The moveable

extremity gave the results of the two lower extremities which measured the maximum cephalic width and length.

The facial nerve enters the parotid gland and usually divides into

temporofacial and cervicofacial trunks. These trunks subsequently

divide and emerge from the parotid gland to radiate anteriorly, and

are commonly classified as temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal

mandibular, and cervical branches [1].

The preauricular and/or retromandibular area was dissected to

expose the temporal and cervicofacial branches of the facial nerve

(Fig. 1A). The distances measured were: (1) from the acustic meatus to the first of the temporal branches when it crossed the central

point of the superior and inferior margins of the zygomatic arch (dis-

107

Facial nerve distances and the TMJ

Figure 1 A. Exposure of the temporal and cervicofacial branches of the facial nerve.

B (Distance A) distance from the acustic meatus to the first of the temporal branches when it crosses the central point of the superior and inferior

margins of the zygomatic arch. C (Distance B) distance from the acustic meatus to the cervicofacial branch at the level of its median initial portion.

D (Distance C) distance from the anterior margin of the tragus to the first temporal branch at the point were it crosses an imaginary line between the

tragus and the condylium cranial point.

108

Woltmann et al.

tance A in Fig. 1B), (2) from the acustic meatus

to the cervicofacial branch at the level of its

median initial portion (distance B in Fig. 1C),

and (3) from the anterior margin of the tragus to

the first temporal branch at the point where it

crossed an imaginary line between the tragus

and the condylium cranial point (distance C in

Fig.1D). A further measurement included the

number of divisions of the temporal branch

when it crossed the basal portion of the zygomatic arch.

To compare the differences among the cephalic indexes, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test

complemented by a multiple comparison test.

When no significant differences were observed

among the same indexes, these were grouped to

form a single sample. The Mann-Whitney test

was used to study the possible differences between the sexes and ethnic groups. In all cases,

the rejection level for the null hypothesis was

P < 0.05 (5%) [5].

RESULTS

For distance A (the distance from the

acustic meatus to the first of the tempoC

ral branches when it crosses the central

point of the superior and inferior margins of the zygomatic arch), values between 0.7 cm and 3.2 cm were obtained,

with a predominance of cases at 1.0 cm

and 1.5 cm (10 each) and a mean distance of 1.54 0.47 cm (Fig. 2A).

For distance B (the distance from the

acustic meatus to the cervicofacial

branch at the level of its median initial

portion), values between 1.2 cm and 3.3

Figure 2. Frequency distributions of distances A (panel A), B (panel

cm were obtained, with a predominance

B) and C (panel C).

of cases at 2.1 cm (12 cases) and a mean

distance of 2.19 0.49 cm (Fig. 2B).

For distance C (the distance from the anterior margin of ences between Caucasians and Negroes (Table 3). There

the tragus to the first temporal branch at the point where it were significant differences between males and females

crosses an imaginary line between the tragus and the for distances A and C (Table 4). Significant differences for

condylium cranial point), values between 1.1 cm and 3.1 cm distance B were also observed between mesocephalic Cauwere obtained, with a predominance of cases at 2.1 cm (12 casian males and females and between Negro males and

brachycephalic females. Our sample contained no

cases) and a mean distance of 2.05 0.41 cm (Fig. 2C).

The number of temporal branches of the facial nerve at dolicocephalic female, so no comparison with the correthe point where they crossed the zygomatic arch varied sponding males was possible (Table 5).

from 1 to 4 [frequencies of 16%, 52%, 24% and 8% for

one, two, three and four branches, respectively].

Significant differences were found for distance B, be- DISCUSSION

tween mesocephalic and dolicocephalic Caucasian males

(Table 1) and between mesocephalic and brachycephalic

The lowest value found for distance A was 0.7 cm, which

Negro males (Table 2). There were no significant differ- was almost the same as the 0.8 cm obtained by Al-Kayat and

109

Facial nerve distances and the TMJ

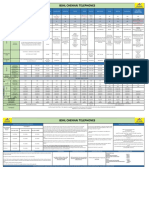

Table 2. Statistical comparisons of distances A, B and C

between Negro, male cadavers, according to cephalic type

(distances in cm).

Table 1. Statistical comparisons of distances A, B and C

among Caucasian male cadavers, according to cephalic

type (distances in cm).

Distance

Comparison

Distance

NS

NS

NS

Comparison

Mesocephalic (1.55) Brachycephalic (1.62)

Mesocephalic (1.55) Dolicocephalic (1.57)

Brachycephalic (1.62) Dolicocephalic (1.57)

NS

NS

NS

Mesocephalic

(1.47) Brachycephalic (1.68)

Mesocephalic

(1.47) Dolicocephalic (1.87)

Brachycephalic (1.68) Dolicocephalic (1.87)

Mesocephalic

(2.26) Brachycephalic (2.44) NS

Mesocephalic

(2.26) Dolicocephalic (2.95) <0.05

Brachycephalic (2.44) Dolicocephalic (2.95) NS

Mesocephalic (1.76) Brachycephalic (2.3)

Mesocephalic (1.76) Dolicocephalic (2.1)

Brachycephalic (2.3) Dolicocephalic

2.1)

<0.05

NS

NS

Mesocephalic

(2.08) Brachycephalic (2.18)

Mesocephalic

(2.08) Dolicocephalic (2.32)

Brachycephalic (2.18) Dolicocephalic (2.32)

Mesocephalic (2.0) Brachycephalic

Mesocephalic (2.0) Dolicocephalic

Brachycephalic (2.04) Dolicocephalic

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

Table 4. Statistical comparisons of distances A and C

according to gender (distances in cm).

Table 3. Statistical comparisons of distances A, B and C

between Caucasians and Negroes (distances in cm).

Distance

Comparison

Caucasian (1.55) - Negro (1.54)

NS

Caucasian (2.25) - Negro (2.12)

NS

Caucasian (2.10) - Negro (2.02)

NS

(2.04)

(2.21)

(2.21)

Distance

Comparison

Male (1.59) - Female (1.25)

<0.05

Male (2.09) - Female (1.82)

<0.05

For Tables 1, 2 and 3: Distance A - distance from the acustic meatus to the first of the temporal branches when it crosses the central point

of the superior and inferior margins of the zygomatic; distance B - distance from the acustic meatus to the cervicofacial branch at the level of

its median initial portion; distance C - distance from the anterior margin of the tragus to the first temporal branch at the point where it crosses

an imaginary line between the tragus and the condylium cranial point. NS, non-significant.

Statistical comparisons done with the Kruskal-Wallis test

Table 5. Statistical comparisons of distance B between

males and females according to the cephalic index and

race (distances in cm).

Mesocephalic

Brachicephalic

Race

Male

Female

Male

Female

Caucasian

(2.26)

(1.4)

<0.05

(2.44)

(2.15)

NS

Negro

(1.76)

(2.08)

NS

(2.30)

(1.8)

<0.05

P<0.05 (Mann-Whitney test), NS, non-significant

Distance B - distance from the acustic meatus to the cervicofacial

branch at the level of its median initial portion.

110

Bramley [1]. On the other hand, the mean distances of 1.54

cm we obtained was lower than the 2.0 cm reported by the

latter authors, and indicated that the cadavers examined here

generally had lower values. Since the smallest distance was

0.7 cm, great care must be taken when performing the preauricular incision to approach the TMJ as this incision is generally done close to the temporal branch. An incorrect procedure may lead to motion paralysis, and compression during

retraction can cause neuropraxia.

The lowest value found for distance B was 1.2 cm and the

mean distance was 2.19 cm, both of which were similar

to the 1.5 cm and 2.3 cm, respectively, obtained by Al-Kayat

and Bramley [1]. These values suggest that during preauricular, endaural and postauricular approaches, the incision

must not be extended below the ear lobe, otherwise motion

paralysis due to neurotmesis or neuropraxia may develop.

For distance C, the smallest value obtained was 1.1 cm.

Thus, when the surgeon uses the tragus as a reference for

the preauricular approach, the incision must be placed

within a safety margin based on the smallest measurement,

in order to avoid damage to the temporal branch.

In most cases (84%), there were two or more temporal

branches. We presume that the greater the number of

branches, the lower the risk of permanent paralysis,

since other branches could partially compensate for the

deficit in sensory input caused by the lesion. Indeed, Gosain

et al. [4] state that, because of the high percentage of

individuals with more than one branch and the numerous

communications observed among the branches of the

temporal nerve, neurotmesis of one or more branches does

not mean permanent paralysis, and recovery may occur.

Ethnic origin, sex and cephalic index did not significantly

affect the three distances measured when Caucasians and

Negroes were compared. When the influence of sex was

evaluated within each ethnic group, males had significantly

greater values for distances A and C.

When the distances within ethnic groups were compared

based on the cephalic index, dolicocephalic Caucasian males

had a significantly greater distance B than mesocephalic

males (Table 1), and brachycephalic Negro males had higher

values than mesocephalics (Table 2). Thus, cephalic index

apparently affects distance B. This observation indicates

that surgical procedures involving the area covered by

distance B require special consideration in males.

In conclusion, distances A and B were similar to those

reported by Al Kayat and Bramley [1] for more homogeneous populations. This finding suggests that the genetic

miscegenation of races in Brazil does not influence the

distances of the facial nerve branches from the temporomandibular joint. However, these distances are influenced

by the cephalic index and sex. These results thus provide

additional data which may be useful for those performing

preauricular incisions to access the temporomandibular joint.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the Descriptive and Topographical

Laboratory of Anatomy (Universidade do Vale do Itaja) and

Dr. Herclio Pedro da Luz, for valuable collaboration in this study.

Dr. Bruno Knig Jnior (Departamento de Anatomia, Universidade

de So Paulo) provided helpful criticisms of this paper.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Al Kayat A, Bramley P (1979) A modified pre-auricular approach to the temporomandibular joint and

malar arch. Br. J. Oral Surg. 17, 91-103.

Brando LG, Ferraz AR (1989) Cirurgia de Cabea e

Pescoo. Roca: So Paulo.

Ellis III E, Zide MF (1995) Surgical Approaches to the

Facial Skeleton. Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia.

Gosain AK, Sewall SR, Yousif NJ (1997) The temporal

branch of the facial nerve: how reliably can we predict its path? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 99, 1224-1233.

Holander M, Wolfe DA (1973) Non-Parametric Statistical Methods. John Wiley and Sons: New York.

Kreutziger KL (1984) Surgery of temporomandibular

joint. Surgical anatomy and surgical incisions. Oral

Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 58, 637-646.

Nellestam P, Eriksson L (1997) Preauricular approach

to the temporomandibular joint. A postoperative

follow-up on nerve function, hemorrhage and

esthetics. Swed. Dent. J. 21, 19-24.

Sicher H, Dubrull EL (1991) Anatomia Oral. 8th ed.

Artes Mdicas: So Paulo.

Received: September 6, 2000

Accepted: February 2, 2001

111

You might also like

- Profession Tax Procedure OnlineDocument1 pageProfession Tax Procedure Onlinehemanvshah892No ratings yet

- AOMSI Calender of Events 2024 FinalDocument4 pagesAOMSI Calender of Events 2024 Finalsevattapillai100% (1)

- Tesis Artcl 13Document6 pagesTesis Artcl 13Setu KatyalNo ratings yet

- Plan Vouchers 12092019Document2 pagesPlan Vouchers 12092019sevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Closed Reduction Nasal Fracture Post Op InstructionsDocument2 pagesClosed Reduction Nasal Fracture Post Op InstructionssevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Penjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisDocument28 pagesPenjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisWitri Septia NingrumNo ratings yet

- Praveena Clinic Visiting CardDocument1 pagePraveena Clinic Visiting CardsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Basic Preprosthetic SurgeryDocument27 pagesBasic Preprosthetic SurgerysevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Oral LymphangiomaDocument8 pagesOral LymphangiomasevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- SBV Dissertation Template 2017Document22 pagesSBV Dissertation Template 2017sevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics in Oral & Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument50 pagesAntibiotics in Oral & Maxillofacial SurgerysevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Best Practices OMFS DEPTDocument2 pagesBest Practices OMFS DEPTsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Sterilization of ArmamentariumDocument41 pagesSterilization of ArmamentariumsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Sterilization and AsepsisDocument48 pagesSterilization and AsepsissevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Nerve InjuriesDocument39 pagesNerve InjuriessevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Life and Work of Shri Hans Ji MaharajDocument75 pagesLife and Work of Shri Hans Ji Maharajsevattapillai100% (1)

- DNA Probes and Primers in Dental PracticeDocument6 pagesDNA Probes and Primers in Dental PracticesevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Lymphangioma of The Tongue PDFDocument3 pagesLymphangioma of The Tongue PDFsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Life of Gajanan Vijay Granthi UneditedDocument63 pagesLife of Gajanan Vijay Granthi UneditedsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Congenital Sublingual CystDocument5 pagesCongenital Sublingual CystsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Oral Lesions in Neonates PDFDocument8 pagesOral Lesions in Neonates PDFsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Jackie ChanDocument1 pageJackie ChansevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Lymphangioma of The TongueDocument3 pagesLymphangioma of The TonguesevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study On The Use of A Dental Dressing To Reduce Dry Socket Incidence in SmokersDocument5 pagesA Retrospective Study On The Use of A Dental Dressing To Reduce Dry Socket Incidence in SmokerssevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Periapical Lesions - A Review of Clinical, Radiographic, and Histopathologic Features PDFDocument7 pagesPeriapical Lesions - A Review of Clinical, Radiographic, and Histopathologic Features PDFsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Congenital Ranula in A Newborn A Rare PresentationDocument3 pagesCongenital Ranula in A Newborn A Rare PresentationsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Oral Lesions in NeonatesDocument8 pagesOral Lesions in NeonatessevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Using Hyaluronic Acid On The Extraction SocketsDocument5 pagesThe Effects of Using Hyaluronic Acid On The Extraction SocketssevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Post-Extraction Complication Course PDFDocument11 pagesPost-Extraction Complication Course PDFsevattapillai100% (1)

- Nonsurgical Management of Periapical LesionsDocument11 pagesNonsurgical Management of Periapical LesionssevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CC 109 - MLGCLDocument25 pagesCC 109 - MLGCLClark QuayNo ratings yet

- SanamahismDocument7 pagesSanamahismReachingScholarsNo ratings yet

- y D Starter PDFDocument13 pagesy D Starter PDFnazar750No ratings yet

- Kenoyer, Jonathan M. & Heather ML Miller, Metal technologies of the Indus valley tradition in Pakistan and Western India, in: The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, 1999, ed. by VC Piggott, Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, pp.107-151Document46 pagesKenoyer, Jonathan M. & Heather ML Miller, Metal technologies of the Indus valley tradition in Pakistan and Western India, in: The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, 1999, ed. by VC Piggott, Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, pp.107-151Srini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Mosaic TRD4 Tests EOY 1Document4 pagesMosaic TRD4 Tests EOY 1MarcoCesNo ratings yet

- How Order Management Help E-Commerce Increase Performance During The Pandemic PeriodDocument4 pagesHow Order Management Help E-Commerce Increase Performance During The Pandemic PeriodInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Lecture05e Anharmonic Effects 2Document15 pagesLecture05e Anharmonic Effects 2Saeed AzarNo ratings yet

- DP Biology - Speciation Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesDP Biology - Speciation Lesson Planapi-257190713100% (1)

- A Beginner Guide To Website Speed OptimazationDocument56 pagesA Beginner Guide To Website Speed OptimazationVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- DECLAMATIONDocument19 pagesDECLAMATIONJohn Carlos Wee67% (3)

- Hormones MTFDocument19 pagesHormones MTFKarla Dreams71% (7)

- Take Home Assignment 2Document2 pagesTake Home Assignment 2Kriti DaftariNo ratings yet

- Match Headings Questions 1-5Document2 pagesMatch Headings Questions 1-5Aparichit GumnaamNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature ReviewRochelle CampbellNo ratings yet

- Jean Faber and Gilson A. Giraldi - Quantum Models For Artifcial Neural NetworkDocument8 pagesJean Faber and Gilson A. Giraldi - Quantum Models For Artifcial Neural Networkdcsi3No ratings yet

- Week 1Document3 pagesWeek 1Markdel John EspinoNo ratings yet

- GRADE 8 3rd Quarter ReviewerDocument9 pagesGRADE 8 3rd Quarter ReviewerGracella BurladoNo ratings yet

- IA Feedback Template RevisedDocument1 pageIA Feedback Template RevisedtyrramNo ratings yet

- Skittles Project CompleteDocument8 pagesSkittles Project Completeapi-312645878No ratings yet

- Real Options Meeting The Challenge CopelandDocument22 pagesReal Options Meeting The Challenge CopelandFrancisco Perez MendozaNo ratings yet

- Dental MneumonicDocument30 pagesDental Mneumonictmle44% (9)

- Quantitative Option Strategies: Marco Avellaneda G63.2936.001 Spring Semester 2009Document29 pagesQuantitative Option Strategies: Marco Avellaneda G63.2936.001 Spring Semester 2009Adi MNo ratings yet

- President Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Kenya@50 Celebrations at Uhuru Gardens, Nairobi On The Mid-Night of 12th December, 2013Document3 pagesPresident Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Kenya@50 Celebrations at Uhuru Gardens, Nairobi On The Mid-Night of 12th December, 2013State House KenyaNo ratings yet

- The Best WayDocument58 pagesThe Best Wayshiela manalaysayNo ratings yet

- Cacao - Description, Cultivation, Pests, & Diseases - BritannicaDocument8 pagesCacao - Description, Cultivation, Pests, & Diseases - Britannicapincer-pincerNo ratings yet

- 11 Rabino v. Cruz 222 SCRA 493Document4 pages11 Rabino v. Cruz 222 SCRA 493Joshua Janine LugtuNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics For Contemporary Decision Making 9th Edition Black Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesBusiness Statistics For Contemporary Decision Making 9th Edition Black Solutions ManualKevinSandovalitreNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Managerial and Leadership SkillsDocument19 pages21st Century Managerial and Leadership SkillsRichardRaqueno80% (5)

- Wedding Salmo Ii PDFDocument2 pagesWedding Salmo Ii PDFJoel PotencianoNo ratings yet

- Ir21 Geomt 2022-01-28Document23 pagesIr21 Geomt 2022-01-28Master MasterNo ratings yet