Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices: From Social Analytics To Explanatory Narratives

Uploaded by

Marc GarcelonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices: From Social Analytics To Explanatory Narratives

Uploaded by

Marc GarcelonCopyright:

Available Formats

bl

is

hi

ng

THE DEVELOPMENTAL

HISTORY OF HUMAN SOCIAL

PRACTICES: FROM SOCIAL

ANALYTICS TO EXPLANATORY

NARRATIVES

up

Pu

Marc Garcelon

G

ro

ABSTRACT

(C

)E

er

al

Purpose The diversity of social forms both regionally and historically

calls for a paradigmatic reassessment of concepts used to map human

societies comparatively. By differentiating social analytics from

explanatory narratives, we can distinguish concept and generic model

development from causal analyses of actual empirical phenomena. In so

doing, we show how five heuristic models of modes of social practices

enable such paradigmatic formation in sociology. This reinforces Max

Webers emphasis on the irreducible historicity of explanations in the

social sciences.

Methodology

Explanatory narrative.

Social Theories of History and Histories of Social Theory

Current Perspectives in Social Theory, Volume 31, 179 220

Copyright r 2013 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved

ISSN: 0278-1204/doi:10.1108/S0278-1204(2013)0000031005

179

180

MARC GARCELON

Findings

A paradigmatic consolidation of generalizing concepts,

modes of social practices, ideal-type concepts, and generic models presents a range of theoretical tools capable of facilitating empirical analysis as flexibly as possible, rather than cramping their range with overly

narrow conceptual strictures.

Research implications To render social theory as flexible for practical

field research as possible.

Originality/value

Develops a way of synthesizing diverse theoretical

and methodological approaches in a highly pragmatic fashion.

bl

is

hi

ng

Keywords: Explanatory narrative; models; types; variable analysis

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

Sociology approaches the comparative history of human societies by formulating concepts, models, and causal hypotheses presupposing scientific

autonomy from both common sense and political expediency. Yet little

disciplinary agreement regarding how to do this

how to fashion what

Thomas Kuhn termed a paradigm in the empirical sciences (Kuhn, 1962)

has emerged in sociology, or for that matter in the social sciences writ

large. By separating the development of concepts and models from that of

causal hypotheses, we can move toward resolving this problem by distinguishing the analytic of human society from specific causal accounts

social scientists propose.1 Such a distinction allows for a robust yet flexible

process of sociological concept and model formation attuned to the contingencies that field research requires in developing causal hypotheses.

Moreover, distinguishing a social analytic of concept development, from

the formulation of causal hypotheses, in turn helps clarify why what are

here called explanatory narratives should methodologically predominate

over the isolation of independent and dependent variables across cases

what Andrew Abbot calls the variables paradigm (Abbott, 1992).

Indeed, the isolation of independent and dependent variables across cases

will be shown to more accurately serve a useful but auxiliary method to

explanatory narrative. As we will see, these methodological issues also converge with a number of important substantive issues in social theory.

THE ANALYTIC OF HUMAN SOCIETY

As many animals are social

from ants and bees to varieties of fish,

birds, and mammals the concept of society per se is not specific to human

181

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

beings. Conceptual universals in the social sciences

here called

anthrogeneric concepts entail distinguishing human societies from those of

other species. Two such anthrogeneric concepts culture and institutions

do this by mapping the boundary conditions of the social sciences per se,

and thus form a logical starting point for mapping the social analytic.2

Indeed, culture and institutions together distinguish Homo sapiens as a

species-being from other living social species today.3

hi

ng

The Anthrogeneric Concepts of Culture and Institutions

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

Culture in the social sciences entails meaning, more specifically, linguistic

meaning and other forms of representation enabled by language. Indeed,

one cannot separate a human society from its culture except in an analytic

sense, for human sociation is impossible without meanings at least partially

intelligible to others in the society (Griswold, 2008, pp. 11 12). Indeed,

culture is coevolutionary with human society (Bradford, 2012). Yet culture

and its meanings themselves are not sufficient to map the boundary conditions of human society.

For this, one needs the additional concept of institution. An institution

is an obligatory form of getting by and getting along in an established

social setting (Garcelon, 2010). Violations of institutional norms trigger

responses that involve some significant cost in resources, time or status,

and sometimes provokes marginalization, sanctions, exclusion from the

situation in which given institutions are effective, banishment, incarceration, or even death. In contemporary societies, institutions are often formalized in laws, legal regulations, and various codes of conducts such as office

rules, university handbooks, and the like. Yet for much of human history,

members of society could not read

indeed, the historically longest-term

variety of human society was hunter-gatherer society, though we have only

fragmentary knowledge concerning such societies from the rough evolutionary emergence of Homo sapiens about 150,000 years ago, to today,

when the remnants of hunter-gatherer societies are dying out.4

Prior to the invention of writing, societies were organized through highly

ritualized institutions reproduced through ceremonies, festival days, rites,

and the like. Such societies are often designated oral societies by anthropologists and sociologists emphasizing that such societies lacked a written language (Goody & Watt, 1987). In oral societies, familiarity with institutional

expectations remains customary, a matter of individuals developing a sensibility through rituals and other patterns of repetition tied to senses of

182

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

identity, belonging, and distinction. Not showing implicit degrees of respect

at important rituals

rituals marking everything from birth to death and

much of life in between risks degrees of disapproval, shunning, or worse.

Since in some circumstances, institutional violations in oral societies may

result in the offenders death, referencing customary institutions as informal institutions as, unfortunately, often occurs is misleading.

The invention of writing in itself is not sufficient to move toward formalization of institutions. Indeed, when only a small fragment of persons can

read, and when texts remain handwritten, institutional norms remain overwhelming enforced through customary means. The technological advances

of the printing press and the diffusion of reading skills in societies made

formalization of institutions possible.5 Indeed, codes of law in the modern

sense are an example of this, and spurred the subsequent development of

handbooks of conduct, procedural norms, and the like. Such formal codification entails patterns of institutional steering of behavior in ways that

enable large-scale organization and the processes Max Weber called

bureaucratization to develop (1978, p. 956).

Emile Durkheim conceptualized observable patterns of human behavior

associated with institutions in terms of social integration, moral regulation, and solidarity,6 all of which underscore that institutions entail

both cultural intelligibility and expectations of subordination of individual

behavior to norms in the broadest sense. As conformity to institutions

entails some degree of routine and habit normalized psychologically on a

day-to-day basis in human social groups, institutions steer social life to a

substantial degree, giving rise to patterns that may persist for extended

periods. For instance, formal codification legality facilitates commercial

activity by imposing respect for laws governing private property and contractual obligations, stabilizing markets over periods of time. Institutions

are thus the primary patterning element of human social relationships.

A colloquial language stands an archetypical example of an institution.

a

Here we begin by distinguishing the analysis of a linguistic capacity

biological trait of human beings from colloquial language as an institution.7 In this sense, a colloquial language entails development of a biological capacity in a specific human social context. This context in turn

provides the framework for learning to understand and speak, and learning

to understand and speak simultaneously entails learning social conventions

so that one can express oneself in a meaningful way to others. The skill of

practical language use we call competence in a specific spoken language in

fact embodies aspects of an archetypal institution, insofar as observance

of minimal linguistic norms is the precursor for a human to be able to

183

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

function at all beyond the competence of a toddler. This in turn underscores a distinctive aspect of colloquial language, namely, colloquial language largely has no disciplinary apparatus, the only institution that

lacks one.8 Indeed, what ensures minimal conformity with linguistic conventions is the fact that intelligibility per se requires such conformity to

achieve intelligibility with interlocutors in any linguistic interaction at all.

Of course, the use of language is involved in all other institutions, and the

more elaborate it becomes, the more ritualized, formalized, or specialized it

becomes. Thus in certain situations beyond instances of everyday practical

communication and banter, not following institutional obligations regarding the use of language can trigger penalizing responses by members of a

disciplinary apparatus

whether by certain clan figures in a hunter-gatherer society, staffs of authorities in agrarian kingdoms, or by law enforcement, legal organizations, courts, and other managerial bodies charged

with enforcing institutional norms in highly bureaucratized contemporary

societies such as the United States today.

There are certain circumstances, however, where even use of colloquial

language in a context not explicitly limited by ritual, formal, or specialized

concerns regarding language use may provoke action by such disciplinary

apparati, such as using profanities in front of children in public in contemporary America. Indeed, the latter is part of the cultural arbitrary in contemporary American society, the historically irreducible aspects of cultures

in a given society at a given time (Bourdieu, 1991). For the most part,

though, distinctions between colloquial and more ritual, formal, or specialized usages of language intertwine in complex ways with distinctions

among hierarchies within institutional orders in human social relations.

All of this raises an important point: institutions are obligatory in the

sense of mutual expectations, but empirically elicit probabilistic degrees of

conformity. Indeed, this is why most institutions beyond colloquial language entail disciplinary apparatuses. Thus they need to be assessed in

terms of probabilistic criteria, as anticipated by Webers conception of

legitimacy and legitimate order (Ringer, 1997). When the probability of

observance falls below historically variable thresholds, then, institutions

may disintegrate (Garcelon, 2006).

Additional Anthrogeneric Concepts

Of course, many additional anthrogeneric concepts play key roles in the

social sciences. We will briefly review a few key additional such concepts,

184

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

but bear in mind that this review is partial and offered only as a heuristic

device. Among the most basic anthrogenerics stand the concepts of field,

agency, habitus (reflexive) action, institutional paradigm, institutional

order, interests (strategic and symbolic), personality, and many others.

Bear in mind that such anthrogeneric concepts are distinct from what

Weber called ideal-type concepts of historically distinct developmental patterns, such as this worldly religion or bureaucracy, a point developed

below.

A field maps how institutions segment and differentiate particular contexts for particular patterns of interaction and behavior, and by extension,

generate an order that either persists for a period of time with minor,

incidental changes, or, in much rarer circumstances, deeper changes or even

outright disintegration of the field (Bourdieu, 1981). A field is considerably

more than an institution. The latter give coherence and shape to fields and

steer routine behavior and interaction in their contexts. But a field per se is

always more than its institutional architecture. For instance, there are

many particular activities that individuals may engage in at a doctors

office such as reading a magazine or interacting with another patient in a

waiting room

that are not obligatory. Yet medicine as an institutional

reality shapes the most basic behavior in a doctors office, as patients

would not even come to a doctor without some institutional certification of

the practitioner.

Agency refers to the causal significance of human behavior in various

situations. Moreover, agency per se should be distinguished from its

subtypes, habitus and reflexive action.9 Reflexive action here means deliberative action, instances of agency in which conscious deliberation, choice,

and the like play significant roles. Following Pierre Bourdieu, habitus designates a capacity for agency considerably broader than reflexive action

a capacity to engage spontaneously in complex sequences without much

deliberation (Bourdieu, 1984, pp. 169 175). For instance, when the driver

of a car has routinized traffic regulations to the point that she can spontaneously adjust to traffic lights, signs, other drivers, and so forth without

reflectively deliberating about them most of the time, she is often considered a good driver by others.

We will return to agency, habitus, and reflexive action shortly. At this

point, note that habitus entails both institutional and noninstitutional routines. Take a cook at home preparing a meal for her or himself alone

this individual may prepare the meal largely on the basis of routines that

require little in the way of deliberative reflection, and yet there is little that

is institutional about this. On the other hand, if the same person realizes

185

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

institutions

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

they need an ingredient and need to go get it, they then may engage in

some institutionalized routines, such as adjusting to traffic regulations

when driving a car, standing in line at a check-out counter in a grocery

store, and so on.

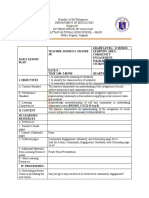

We can distinguish institutional from noninstitutional routines in terms

of a broader habitus, on the one hand, and those aspects of habitus bound

up with institutions, on the other. This latter subset of an individual

habitus we call an institutional paradigm, a disposition toward conventional observance of routines to get by and get along (Garcelon, 2010,

pp. 326 335), as in Fig. 1.

This offers a corrective to a chronic but erroneous tendency among

many Western sociologists to assume that institutions somehow exist on a

different level than agency, with level usually referencing micro

macro distinctions, or sometimes micro meso macro distinctions.10 Yet

placing institutions on a different level than agency generates all sorts of

artificial problems that disappear when one recognizes first, that institutions entail an embodied aspect; and second, that individuals can play causal roles at different levels. Of course, this latter also entails recognizing

that distinctions between the micro as the realm of agency, and the macro

(or meso) as the realm of institutions, make little sense

certainly,

institutional paradigms

institutional orders

embodied

as habits, dispositions,

beliefs, and adjustments

observable as patterns

of behavior which give

apparent order to patterns

of social relations

the core of habitus

the core of

institutional fields

Fig. 1. Institutional Paradigms and Orders. This figure is a slight modification of

Fig. 1 in Garcelon (2010, p. 333).

186

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

individuals such as Hitler, Stalin, or Mao played causally significant roles

at a macro level, and institutional norms sometimes exist only at the micro

scale of very small groups such as religious cults with only a few dozen people, for instance (Mouzelis, 1995, p. 20). Once this is recognized, distinctions between levels

micro, meso, macro

serve simply to differentiate

the scale of a social space.

At this point, then, we have mapped out culture, institution, field,

agency, habitus, reflexive action, and institutional paradigm. Complementing the latter, an institutional order refers to those aspects of an institution

that manifest as routine patterns in social groups. This in turn allows us to

introduce Webers concept of legitimacy, for legitimacy is the felt sensibility

of the rightness or justness of a tribal leadership of some sort, or the

state as an institutional order (Weber, 1978, pp. 31 33), underscoring that

(relational) institutional orders persist due to (embodied) institutional paradigms.11 In the pre-modern world, Weber argued states relied on traditional

forms of legitimacy among their subjects, traditional authority; whereas in

the modern period, he noted the emergence of a new form of legitimacy

among subjects, legal-rational authority, that entailed obedience to authorities out of respect for the law that they might otherwise be disinclined to

obey.12 (Due to time constraints, we leave aside here Webers third variant

of legitimacy, charismatic legitimacy, that he argued may operate in noninstitutional circumstances and which plays an often crucial role in social

change.) Legitimacy is, in essence, an aspect of an individuals institutional

paradigm, namely, that aspect entailing acceptance of a tribal order or

states leadership. These latter in turn constitute what Bourdieu (1990)

called the field of fields, insofar as the state

or a pre-state huntergatherer leadership

sets the boundaries for perception of legitimate

behavior on the part of agents in a given society at a given point in time.

Differentiating institutional orders from institutional paradigms within

broader institutions per se allows considerable conceptual refinement that

maximizes the flexibility of these concepts for empirical research. Indeed,

such research can simply study agency and institutions without worrying

about how to reconcile their assumed theoretical levels. Moreover,

further differentiating institutional paradigms in terms of a sensibility of

legitimacy, on the one hand, and other varieties of routinization of behavior, such as adaptation through adoption of routines of expected conventions in families, schools, businesses, and so on, on the other, allows us to

further differentiate various types of institutions. This refines the relation

between a state and other institutional orders, for a state operates across

other institutions and to an extent legitimizes them by extension as well,

187

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

and thus entails a hierarchization to some degree of institutions and the

institutional paradigms that people develop to adapt to them. In short,

institutional orders per se are broader than the institutional order of a

hunter-gatherer leadership or state, and thus we should expect varying

degrees of differentiation between the degree of legitimacy people develop

toward a hunter-gatherer leadership or state, and the broader institutional

paradigms people develop in relation to various institutional orders and

the fields they enable in various societies.13

As people interact in institutional orders relying on their embodied institutional paradigms, the relation between the social context and how people

understand and convey meaning about it are steered by what Bourdieu

called the doxa of a social world, the everyday conventions that bound

conversation and more elaborate forms of expression to some degree

(Bourdieu, 1991). In a more differentiated society, individuals take a doxa

for granted as they express the meanings of various experiences to one

another in social interaction.

Of course, there are many other anthrogeneric concepts that we do not

have time to discuss here. We will, however, revisit the anthrogeneric

concepts of agency, habitus, and reflexive action shortly, but first we turn to

social analytics that help us comparatively situate societies in regard to one

another. In this way, we will have a minimum range of concepts to place

analysis of agency, habitus, and reflexive action in historical context.

)E

Mapping Five Modes of Social Practices

(C

We can initially map human societies in all their historical and comparative

diversity through the concept of modes of social practice. This conception generalizes from Marxs concept of the mode of production without

assuming any lines of causal determinacy. Rather, five such modes are

offered here heuristically to organize the comparative study of historical

variants of social relations, institutions, and patterns of culture and agency

particular to them. The concept mode signals that all five are anthrogeneric universals in the sense of having existed in all known human societies,

and that variation within and between such modes marks their actual history. In this sense, the concept mode more fully captures this possible

variation and historical depth than either the concepts subsystems or

functions. At the same time, mode allows more range than either of

these concepts in mapping the complexity and diversity of human social

forms, as we shall see.14

188

MARC GARCELON

hi

ng

Mapping modes of social practices onto degrees of institutional differentiation stands a principal aim of empirical research, for such modes represent preliminary concepts

heuristic devices

for the organization of

empirical explanations. Indeed, degrees of institutional differentiation

within modes of social practices vary for contingent, historically irreducible

reasons. For instance, degrees of institutional fusion of modes of social

practices often predominated in premodern history, such as divine kingships.15 Contemporary representative democracies, on the other hand,

embody complex institutional differentiation. In this sense, the five anthrogeneric modes of social practices outlined here represent bridge concepts to

ideal-type concepts and generic models, as discussed below.

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

The Mode of Communication

The very fact of language underscores that all human societies entail specific means and modalities of communication. The differentiation of more

complex communicative forms such as writing, and more elaborate technologies of communication such as books, indicates the utility of differentiating the means of communication from how such means combine with

actual practices. Both means and practices develop as emergent properties

of language appearing at various points in the historical record. This

immediately raises a cautionary note applicable throughout the following

elaboration of modes of social practices: the farther back from the contemporary one goes, the more fragmentary and incomplete evidence becomes,

until we end up making educated guesses compatible with such incomplete evidence.

The mode of communication always subsumes a mode of language.

Language as an actual mode of communication realizes itself both through

a universal language capacity among all Homo sapiens

a capacity that

entails biological aspects, as discussed above

and a specific spoken language, a historical individual (Weber, 1949, pp. 149 152), initially

learned during socialization.16 Thus language as a spoken practice is a specific historical mode of language a unique complex of features we give a

proper name, such as Russian as spoken in the Soviet Union in the 1960s

(Weber, 1949, pp. 83 84, 111 112, 160 171).

Specific languages as historical individuals are in fact instances of institutions, for they are obligatory forms of getting by and getting along in

situations realized through them.17 As noted above, a spoken language in

its most basic colloquial forms entails no disciplinary apparatus, for the

obligatory nature of a spoken language coheres largely spontaneously

those who cannot speak at a practically minimal level of a dominant

189

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

colloquial language in a region are quickly marginalized in social practices

in that region.

Modes of language enable the elaboration of modes of mediation in

human history, such as the invention of writing and the spread of literacy.

Again, early Homo sapiens used artifacts in a representational way in their

burial practices, implicitly differentiating everyday linguistic practices

from the symbols used in such burials, something we know from archaeological evidence. Such modes of mediation have developed in diverse ways

since Neolithic times, as the development of painting, writing, and then

books and other forms of media attest. Obviously, mass literacy and the

rise of first the mass media, and then the multimedia system of recent years,

represent the extent to which such differentiation has gone in the modern

period (Castells, 2000, pp. 355 406). Table 1 represents the mode of

communication.

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

The Mode of Belief

Beliefs help constitute human society by ordering relations between a social

order and its wider environment through beliefs about both community

and the wider world in which it is situated. Specifically, modes of belief

entail ways social groups presuppose some projected order of the world

represented through languages and symbols, but taking more complex

forms than language itself, from mythic ideations to the passing on from

one generation to the next of forms of practical know how, what

Michael Polanyi dubbed tacit knowledge (2009). Claude Levi-Strauss

identified an archaic form of the more complex ideations that language

enables as mythemes (1967, pp. 207 219). As societies become more

complex, a considerable variety of patterns of more elaborate beliefs displace myth, from religions per se in the ancient period of human civilization, to ideologies in more modern times (Levi-Strauss, 1967, p. 205). Such

post-mythical patterns of belief often gain a sacred status through revered

texts such as the Bible or Bhagavad Gita, or a quasi-sacred status through

foundational texts such as the American Constitution. Indeed, reference to

the American Constitution often takes the form of cant across complex

Table 1.

The Mode of Communication.

Mode of Communication Subsuming

(a) The mode of language

(b) The mode of mediation

190

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

hierarchies of fields in the contemporary United States. Patterns of modern

belief closely identified with both the maintenance and contestation of political power develop in ideological forms, a point we return to below in discussing modes of domination.

More modern patterns of belief develop tensions between practical

knowledge and abstract ideations as differences between the is and the

ought. Take for instance the emergence of the modern sciences, which

required extensive institutional changes to legitimize the practices of those

engaged in them, including the piecemeal restriction of political and religious authorities abilities to interfere with scientific practices on the basis

of habitual understandings of elite guardianship of the ought. The history

of the modern sciences thus forms a complex skein of practices distinguishing the is from the ought. Indeed, the whole differentiation of the is

from the ought presupposes the differentiation of cognitive from moral,

legal, magical, and spiritual practices, what Jurgen Habermas calls the

linguistification of the sacred (1987).18

The degree to which such distinctions give rise to actual institutional differentiation remains an empirical question. But in fact tensions between

what Weber called practical concerns like the gathering of foodstuffs, on

the one hand, and ritualized practices such as group ceremonies, on the

other, can be identified even in tacit distinctions between burial artifacts

and simple hunting tools from Neolithic times. We can thus recognize tacit

practical differentiation of modes of cognition from modes of ideation

within modes of belief throughout history, building on Bellahs distinction

between cognitive and symbolic understanding (Bellah, 1973) (Table 2).

The Mode of Kin Reproduction

The mode of kin reproduction stands a third universal mode of social practices entailing four subtypes of such practices. All known human societies

in history placed kinship and the family order in the center of human social

life, something which continues today. Certainly, the understanding of

what family means has varied considerably in human history, with more

extended kin networks predominant in family life in premodern societies,

Table 2.

The Mode of Belief.

The Mode of Belief Subsuming

(i) The mode of cognition

(ii) The mode of ideation

191

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

and the emergence of the nuclear family parents and children limited

at first to late medieval and early modern Britain and some of its colonies

before spreading much more widely outside the Anglo-American world

from the nineteenth century forward (Liljestrom, 1986).

The subtype of kinship constitution stands out immediately here,

and with

through which central bonds of family orders are constituted

them the most basic organization of social life. Here we find birthing and

marital practices, as well as aspects that govern the possibility (or its lack)

of constituting kin ties across societies. Next, the sub-mode of socialization

describes practices signaling in-group boundaries, social hierarchies, and

ones place in a social order. As children are highly dependent on the care

of familial kin networks for many years, at least some modest hierarchization based on age and social respect for the knowledge of elders are universal. From here, we can identify other such socializing practices, from rites

of passage from one social status to another in hunting and gathering

groups, to compulsory schooling in more contemporary societies. Elias

(1969, 1982) described these as parts of the civilizing process.

The mode of health comportment embodies a third variant of such kin

reproductive practices. These are everyday practices of health edification,

maintenance, and interventions ranging from dietary injunctions such as

Orthodox Judaisms forbiddance of shell fish, to expected patterns of dress

in various circumstances at various times. Such understandings presuppose

a conventional, not strictly medical, understanding of health that varies

widely across history. Indeed, what counts as healthy follows conventional understandings.19

Modes of health comportment are often mediated through other social

practices, such as modes of belief. Indeed, considerable overlap between

early magical and health-intervention practices underscores the analytic

nature of the distinctions drawn here

medicine man, for instance,

appeared as a common variant of a magician in hunter-gatherer societies.

Yet distinctions between the practice of magic, religions, and other spiritual

belief systems, on the one hand, and specific modes of health comportment,

on the other, can at least be analytically drawn in early human societies,

though often only becoming clear as societies become more complex. For

instance, we can tacitly distinguish the practices shamans divined regarding

taboos of eating, from the practices of seeking knowledge of the movements of tribal enemies. Indeed, the gaining of autonomy by medical specialists from magical and religious practices is a most modern institutional

fact. In the oral cultures of most kinship societies, for instance, modes of

health comportment remained closely linked to ritual practices of belief,

192

MARC GARCELON

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

one of the reasons that the entire range of health practices has often been

subsumed under analyses of magic and religion in premodern societies.20

Here, by contrast, magical, religious, and other spiritual practices combine

aspects of modes of belief, health comportment, and domination.

The unique human practices of funerary rites compose a fourth subtype

of the mode of kin reproduction, namely, the mode of funerary practices.

Critically, funerary practices are practices of kin reproduction insofar as

they affirm social and natural perceptions of order and continuity in the

face of the existential reality of death.21 In this sense, funerary practices

entail key rites and rituals that maintain a semblance of continuing on in

the face of the death of an individual person. In this sense, funerary practices aim at shoring up and solidifying social practices in the face of an existential trauma that all people sooner or later face.

In doing so, funerary practices generally entail the at least ceremonial

setting apart of various practices associated with them. The social recognition of death in funerary practices underscores the liminal state of death

as a symbolically weighted rite of passage from a living social status to

a symbol of the continuity of the past in the present (Turner,

1969). Historical evidence shows a tight coupling between modes of kin

reproduction

entailing diverse culture practices from marriage to variations of education such as rites of passage and modes of funerary practices.22 The latter entail everything from patterns of ritual grievance for

those seen as mortally injured, to funerary rituals themselves. Table 3

represents the mode of kin reproduction.

(C

The Mode of Economy

In contrast to such socially reproductive kin practices, the mode of economy designates a range of human practices at the center of social science

since the origins of political economy in the second half of the eighteenth

century. Marxs critique of classical political economy framed the economy

as a base determining a superstructure entailing a wide range of other

Table 3.

The Mode of Kin Reproduction.

Mode of Kin Reproduction Subsuming

(a) Mode of kinship constitution (including marital and birthing practices)

(b) Mode of socialization (including education)

(c) Mode of health comportment

(d) Mode of funerary practices

193

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

practices, from politics to culture. The problem with this is, of course, that

it presumed economism, with the economy conceived as determining in

the last instance other aspects of social life. Webers alternative to economism located causal relations in the historically irreducible confluence of

historically unique social relations at specific times, a central aspect of

explanatory narratives explained below.23

In this sense, economic practices, like communicative, belief, or kin practices, can be conceptualized as both constraining and enabling patterns of

social relations over time, and yet not determining them in an a priori

fashion. Economic practices can instead be modeled comparatively in terms

of conceptual generalizations, and then these generalizations can be used as

a tool kit (Swidler, 1986) from which to devise specific accounts of causal

patterns along specific paths. In light of this, we can both acknowledge the

origins of the mode of economy in Marxs concept of the mode of production while differentiating the former from the latter.

First, we reject economic determinism in favor of a Weberian model of

historical contingency. This can be developed in terms of a model of trajectory adjustment where agents rely on their habits and expectations in

anticipating the reproduction of extant institutional arrangements, though

sometimes such anticipation proves erroneous in the face of institutional

change (Eyal, Szelenyi, & Townsley 1998; Garcelon, 2006).24 We can then

fashion a noneconomistic conception of the mode of economy reconstructed

along lines mapped out by Daniel Bell and Manuel Castells in ways that

clarify how to conceptualize economic relations in relation to other social

practices.

One cautionary note regarding the following discussion. Bells analysis

can certainly be criticized in various ways (Postone, 1999, pp. 12 19), however, the following does not strictly adhere to Bell or any of the thinkers

whose work is adapted here. Rather, the adaption of Bell via Castells develops one of his more useful conceptual innovations for a proposal that is

synthetic, not exegetic, in character.

In any case, the mode of economy allows us to recognize a broader range

of work processes and class distinctions that can develop under a particular

institutional ensemble like capitalism than Marx conceptualized. Take for

instance the distinction between laborers working for an hourly wage, and

professionals working for a salary (Castells, 2000). Professionals turn out to

be central to the computer sectors of the contemporary capitalist economy,

for instance, yet they cannot be understood in terms of the capitalist-worker

distinction that Marx mapped as determinant of capitalist society as a whole

precisely because professionals cannot be separated from their key means

194

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

of production, their specialized expertise, in the way workers can be separated from tools (Ehrenreich, 1989, pp. 78 81).

What we see instead is the differentiation of three major classes in leading

capitalist economies since the Second World War, capitalists, workers, and

professionals. In short, the work process can develop in ways that Marx

did not anticipate and still be organized on a capitalist basis. Modifying

Bells earlier differentiation of axial principals in human societies

(Bell, 1999), Castells proposed distinguishing the mode of production (how

social relations are organized to stabilize distinctive power relations in various economies), from the mode of development, how a work process is

organized to produce economic value (Castells, 2000, pp. 13 18).

Economic value in turn functions pragmatically as some metric or ensemble

of metrics some implicit, some explicit that relates the utility of things

and services to measures of worth and effort.

In this way, the productive capacity of a labor process appears as a distinct question from the institutional basis of power relations which both

enables and constrains it. The productive capacity of labor processes can

now be mapped as the ratio of the value of each unit of output to the value

of each unit of input (Castells, 2000, p. 16), though this presupposes some

development of both conceptual and measuring standards to do so. Yet at

least precursors of such standards have always been practically used, though

in rougher and simpler forms going back to hunter-gatherer societies. The

quantification and standardization of such measures under capitalism made

their function as measures explicit as economic ends in themselves, but we

can retrospectively see crude variations of these throughout history, often

implicit in political arrangements. Indeed, economic tribute extracted from

the peasantry turned over to patrons, labor days, and so forth marked

all premodern states (Wolf, 1981).

The emergence of economic growth as the avowed goal of political leadership distinguishes the modern world from premodern societies. The rise

of the modern era thus witnessed widespread changes regarding economic

production, changes that entailed what Weber (1958 [1904]) called the

rationalization of measures of economic output, a protracted outcome of

a whole chain of institutional changes that in the end led to the very idea of

making economic growth the Alpha and Omega of social policy.

Such a championing of economic growth marks both capitalist and

socialist variants of political projects to manage a modern economy, and

operated in earlier capitalist economies dominated by the capitalistworking class distinction, as well as more recent capitalist economies with

three major classes, the capitalists, workers, and professionals. Indeed, the

reorientation of social life to economic growth as an end in itself helps

195

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

us distinguish shifts underway in the technological and organizational

forms of the work process, from the alternative institutional arrangements

of capitalism and socialism within their broader shared orientation to economic growth as an end in itself. Indeed, capitalism and socialism as antagonistic institutional ensembles subsume similar technological arrangements,

as is strikingly clear when one tracks the Soviet mimicking of Fordist factory

organization in the 1930s (Kuromiya, 1988). We can thus differentiate the

institutional umbrella which stabilized industrial work processes as a political form in Fordist and Stalinist factories in the 1930s, from the institutional

arrangements at the shop floor similar in both countries at this time.

Modes of development thus map the technological arrangements by

means of which labor works on matter to generate the level and quality

of surplus (Castells, 2000, p. 16). Such technological arrangements have

institutional dimensions, for instance the role of foremen in supervising

assembly lines in factories producing automobiles in Henry Fords Detroit

or Joseph Stalins Soviet Union.

er

al

G

ro

up

Each mode of development is defined by the element that is fundamental in fostering

productivity in the production process. Thus, in the agrarian mode of development, the

source of increasing surplus results from quantitative increases of labor and natural

resourcesin the production process, as well as from the natural endowment of these

resources. In the industrial mode of development, the main source of productivity lies

in the introduction of new energy sources. (Castells, 2000, pp. 16 17)

(C

)E

We thereby analytically decouple ways of organizing production as a

process from ways of arranging power relations between an economy and

a larger society, with the former mapping modes of development and the

latter mapping modes of production. Thus we can see a wider range of

possible patterns of organization between work processes and political institutions in the modern world, from industrial socialism to informational

capitalism. At the same time, this shifts causal analysis from an abstract

level of predetermined historical stages, to the comparative modeling

of specific historical trajectories dependent on historically irreducible

circumstances. In sum, human societies at various times in various regions

remain dependent on trajectories of social interaction in contingent

historically irreducible situations. This in turn leads to recognition of how

problematic assumptions of universal developmental stages of human

society indeed are. We can map this contingency as in Table 4.

The Mode of Domination

Of course, patterns of domination in history are more than patterns of economic domination, which brings us to mapping out modes of domination

196

MARC GARCELON

Table 4.

The Mode of Economy.

Mode of EconomySubsuming

(a) The mode of production

(b) The mode of development

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

per se. Objections could be raised to the concept mode of domination simply on the basis of evidence of small-scale, egalitarian kinship societies

from prehistoric times, and similar evidence from more recent huntergatherer societies. But at least one form of domination

that of adults

over children

is universal, for obvious reasons. Such universal patterns

of domination also extend to those recognized as knowledgeable about key

processes shamans, medicine men, and other varieties of magicians in

early societies as well as to the growing dependence of the frail, whether

through sickness, child bearing, or age, on stronger adults. We again see

here a practical fusion of analytical modes, here of domination, kinfamilial constitution, and health comportment in hunter-gatherer societies.

The institutional differentiation of modes of domination begins with the

emergence of archaic states (Sagan, 1985, pp. 225 298; Weber, 1978,

pp. 226 234) and runs right down to contemporary antagonisms between

and within different states and social orders in the world today.

Indeed, stable domination over relatively protracted periods of time

entails stable patterns of authority, the voluntary acceptance of obedience

(Weber, 1978, pp. 31 38). Webers concept of legitimacy combines domination and authority to signal acceptance of domination as legitimate by

enough individuals in a society to make some degree of deference to authoritative figures in society obligatory in order to get by and get along.

What happens in cases where domination absent legitimacy occurs?

stateWhen political power is reduced to the mere exercise of coercion

organized terrorism the state as an institution disintegrates and political

power becomes highly unstable and inefficient. Legitimacy as a broadly

expressed loyalty to state authority is thus key to political stability in societies with states. Such legitimacy can only be mapped probabilistically, and

moreover, the mapping itself presents difficult empirical problems unless

we agree to stereotype patterns of motivation in ways that bypass interpretation altogether, a move that has failed repeatedly to provide a generalizable model adequate to empirical cases such as suicide bombings but

which persists in various forms of economism noted above (Garcelon,

2010, p. 347).

197

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

Sometimes, of course, such stereotyping of motivation works in the

sense of generating plausible empirical hypotheses, such as the behavior of

stock holders in a highly capitalistic society such as the contemporary

United States. But when such economic stereotyping of motivation fails to

generate adequate empirical hypotheses of behavior, a more complex array

of methods of interpreting behavior comes into play. No behavior more

starkly embodies such economically irrational agency than loyalty to a

greater social project which requires people to make sacrifices of economic

interests to some greater goal, such as ideational projects of building

socialism, defending the nation, or martyrdom for Allah. And such

ideational projects lie at the heart of modes of domination in history,

signaling a need to trace the sub-mode of legitimacy in order to flesh out

how stable domination works.

Durkheim perceptively captured the sentiments stabilizing legitimacy in

the concept of solidarity, the willingness to sacrifice self-interests for a

greater project (1997 [1893]). And indeed legitimacy entails some minimal

degree of solidaristic commitment in order to stabilize authority for either

a hunter-gather leadership or a state. Differentiating strategic interests

from solidaristic sentiments clarifies and sharpens a somewhat obscure, yet

central, point in Weber. First, we differentiate those who comply with

authority out of simple expedience, from the always shifting

though

incrementally so

number of people in a society at some time x who

embody some felt sense of the legitimacy of authorities. Weber differentiated the two in terms of internal and external aspects of legitimacy,

an unfortunate use of terms that confuses what he actually meant (1978,

pp. 31 33), for both expedience and solidarity are internal in the sense

of being embodied in agents. Webers terminological choice thus obscured

the differentiation of motivations he was driving at.

If we conceive of this differentiation in terms of solidaristic sentiment

and expedient compliance both of which are embodied by agents in various fields we clarify how sociology may distinguish the empirical consequences of degrees of legitimacy embodied by varying people at various

times toward particular institutional authorities. Weber did this be differentiating the normative from the empirical validity of an order (1978,

p. 32). This requires a probabilistic distinction between those motivated

more by solidaristic sentiments, from those motivated more out of

expedience, a problem of empirical analysis that situates perceptions of

cynicism in modern democracies in a sociological light. Certainly, this is

often difficult to carry out in terms of empirical research due to the problem of how to align evidence in relation to various motivations assumed

198

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

as influencing the behavior and interactions of distinct individuals at particular times. Regardless of this methodological difficulty, however, if the

number of individuals motivated by a solidaristic sense of legitimacy

toward core state institutions becomes too small relative to a society as a

whole, institutional authority may rapidly disintegrate into contending

power centers, a phenomenon often designated a revolutionary situation

in the modern period (Tilly, 1993, pp. 10 14).

The differentiation of solidaristic sentiments from the expedient pursuit

of interests, however, is itself inadequate for assessing patterns of agency

in relation to constellations of political power. One must also assess

degrees of affectation and habituation to adequately track the social nuances involved. Foucault called this the microphysics of power (1979), indicating the degree to which patterns of authority are broadly routinized as

habit with minor variations from individual to individual. Indeed, a complex range of motivations and habits are at work in any population, from

intelligible emotional states like love and hate, to the simple routines of

habit. How such patterns articulate with the embodiment and representation of political power in the more conventional sense is the stuff of

history. For instance, the powerful effects of ritualized hatred and communal identification in motivating warfare and terrorism stand an obvious

example.

Legitimacy, then, serves as the glue holding institutional authority

together. Indeed, legitimacy is an embodied aspect of institutions of domination, a solidaristic belief in the authority of established social powers.

In this sense, such belief forms a core aspect of institutional paradigms

central to maintenance of a mode of domination as routine social order.

Legitimacy thus constitutes a special case of belief whether more customary or elaborated through doctrines and other such codes

that can be

differentiated from other patterns of ideation in a social order. Often ritualized and developed as mythologies in premodern societies, such ideations

sometimes develop into ideologies and legal doctrines in modern states

(Levi-Strauss, 1967). Legitimacy thus represents a bridge case between

modes of belief and modes of domination in any society, underscoring the

analytic character of the distinctions drawn here and the need to track

actual patterns of institutional differentiation empirically.

In most cases, organized hierarchies figure centrally in institutional

orders. Indeed, the latter depend on the embodiment of at least traces of

solidaristic sentiment. Thus hierarchical authority presupposes embodiment

of moral facts of solidarity in a sense of conscience and more diffuse and

improvised patterns of habitus.

199

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

Thanks to the authority invested in them, moral rules are genuine forces, which confront our desires and needs, our appetites of all sorts, when they promise to become

immoderateThey contain in themselves everything necessary to bend the will, to contain and constrain it, to incline it in such and such a direction. One can say literally that

they are forces. (Durkheim, 1973, p. 41)

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

Such legitimacy enables institutions to persist over time, as embodied

dispositions stabilize legitimate authority, the core of institutional orders as

obligatory patterns of social relations over time.

We have thus reconstructed Weber through concepts introduced by

Durkheim and Bourdieu, giving us a robust theory of what makes institutional hierarchy possible in the first place. Indeed, the mode of legitimacy

is central to all known human societies, as pre-state varieties of legitimate

authority play important roles in hunter-gatherer societies, though in such

cases legitimacy remains tightly coupled with clan and tribal customs and

rituals. The fusion of other domains mapped out in the modes of social

practices mapped above, with the core social practices of legitimacy prior

to modern representative democracies, had to undergo significant differentiation before the social sciences were even possible. Of course, history

presents a wide diversity of modes of domination and legitimacy, which we

can not go into here beyond noting the elaborate institutional differentiation that marks the rise of modern constitutional democracies, Soviet-type

societies, and the like.25

Certainly, legitimacy

though very diverse in terms of degrees and

types of embodiment stands at the core of any mode of domination capable of achieving institutional coherence for some span of time. But domination also usually entails distinctive hierarchies of organization and

distinctive means of applying force, conceptualized here as the mode of

organization and the mode of destruction.

Kinship patterns stand as the most archaic mode of organization in history, and continue to be fundamental in all more complex organizational

patterns. Nothing captures this more clearly than the resonance of the

vague phrase family values in recent American politics. Indeed, extended

family groupings kinship were reorganized around clusters of warriors

in a new type of hierarchy in ancient times, patriarchal domination. Weber

described this in terms of the emergence of the patriarch and his staff

(1978, pp. 228 231). This pattern served as the basis of the archaic state in

all known cases, which entailed displacing pre-state patterns of organization such as clans and tribes (Sagan, 1985). The archaic state, in turn,

enabled the invention of writing in some cases, at first limited to scribes,

religious figures, and other patriarchal elites in a pattern Goody and Watt

200

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

(1987) called oligoliteracy. Thus the shift from a kinship to a patriarchal

pattern of domination enabled in some cases the shift away from a purely

oral pattern of transmitting knowledge and ritual, to a pattern in which a

social elite wielded new modes of mediation bound up with the secrets of

literacy itself. We again see here an instance of tight coupling of various

modes, here the mode of organization and the mode of mediation. Indeed,

for thousands of years, oligoliteracy remained tightly coupled with the

patriarchal mode of organization. Today, we tend to construe organization

per se with formal organizations in the sense of bureaucracies, though this

latter is only a subcategory of organization. Moreover, we also tend to designate all formal organizations as bureaucracies, a problematic designation

with certain organizational forms such as fascistic or Marxist-Leninist

party states (Garcelon, 2005, pp. 27 35).

The mode of destruction (Foucault, 1970) stands the final aspect of the

mode of domination. To be realized in practice, legitimacy and organization must combine with instrumentalities of domination. We can thus map

the mode of destruction in terms of implements

spears, swords, guns,

and the like

and how people are ordered in relation to them

warrior

bands, militias, armies, and so on. All of these gain coordination through

relations of destruction, the hierarchical pattern of command and control

that sets such instrumentalities into motion. Again, the differentiation of

such instrumentalities of destruction used by agents in distinct institutional

and noninstitutional contexts marks human history. In prehistory, for

instance, we see a generalized fusion of such instrumentalities with modes

of development, specifically hunting tools. Institutional differentiation of

the mode of destruction followed from the creation of hierarchies of legitimate command with the rise of archaic states. Indeed, the owl of Minerva

flies only at dusk, for only the perspective of full differentiation in the modern world places the mode of destruction in such clear perspective. Indeed,

the recent development of substate terrorism appears a tactic developed

to counter the seamless web of domination engendered by the modern

state. We thus see that the mode of domination entails modes of legitimacy,

organization, and destruction as mapped in Table 5.

The differentiation of modes of communication, belief, kin reproduction, economy, and domination is the stuff of institutional history. The

above five modes and various sub-modes are analytic distinctions, insofar

as variations of all five are either known or assumed present in all instances

of human society since the coevolutionary differentiation of languages, on

the one hand, and of Homo sapiens from earlier, now extinct human

species, on the other. Certainly, the institutional differentiation of such

201

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

Table 5.

The Mode of Domination.

Mode of DominationSubsuming

(a) The mode of legitimacy

(b) The mode of organization

(c) The mode of destruction

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

modes tended to be slight in hunter-gatherer societies, about which our

knowledge remains only fragmentary at best take, for instance, the differentiation of sacred and profane times, or the ritualistic ordering of ceremonies, meals, birth and death events, hunting expeditions, and so on. In

hunter-gatherer societies, such differentiation entails at best a modest

specialization of tasks, and little institutional differentiation in terms of the

formation of distinct fields.

Indeed, there is nothing intrinsic about such patterns of differentiation:

such anthrogeneric modes of social practices remain only heuristic devices

for arranging evidence of actual paths of institutional differentiation in history. As we apply anthrogeneric concepts to specific circumstances, and

then engage in secondary, comparative-historical generalizations on the

basis of such analyses of specific circumstances, we generate what Weber

called ideal-type concepts. Such ideal types like generic models discussed

below show in practice how the social analytic bridges to the analysis of

specific circumstances, and from here to the formulation of specific empirical hypotheses, something discussed in more detail below.

For now, Fig. 2 presents a very brief overview of how to historically

organize some basic ideal-type concepts from Webers Economy and

Society, indicating the rich complexity involved in tracking these patterns

empirically. The patterns of institutional differentiation mapped by ideal

types remain tightly coupled to patterns of agency and reflexive action in

particular times and places, and thus we turn to a few important observations about agency and action as a bridge to the following discussion of

explanatory narratives.

Agency and Reflexive Action

Two common traits regarding human agency have predominated in AngloAmerican sociology in recent decades, a tendency to conceptualize agency

simply as action per se (and individuals as actors), and a tendency to

202

MARC GARCELON

time

period

categories

of ideal types

antiquity

pre-history

societies &

economies

hunterOikos

gatherer

societies

(clans,

tribes, etc.)

antiquity

through early

modernity

agrarian

societies

modernity

more capitalistic societies

more socialistic societies

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

patriarchal feudal

representative democracies

states

plebiscitarian authority

patrimonial

hi

ng

varieties of dictatorships

Pu

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------kinship

extended

authorities bureaucracies

households and staffs

G

ro

dominant

organizational form

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------charismatic charismatic charismatic charismatic

up

non-routine, non-state &

founding forms of

authority

bl

is

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------traditional traditional traditional traditional and legal-rational

routine forms of

authority

(C

)E

er

al

Fig. 2. Temporal Ordering of Some Basic Ideal Types of Societies, States,

Organizations, and Authorities in Webers Economy and Society. Note: Weber did

not track such type concepts in unilinear-evolutionary terms, that is, he noted that

history has sometimes seen what might appear earlier forms reappearing at later

times, though capitalism, socialism, and for the most part, bureaucracies are

modern. Weber also identified many, many intermediate forms not shown here,

such as the Standestaat in some parts of late medieval/early modern Europe. Also,

the chart makes more schematic some of Webers analyses than they are, obscuring,

for instance, his identification of the medieval Catholic Church as the originator of

early bureaucracy in the Western world.

identify causes in social life external to agency. As a consequence, both an

overburdened concept (action), and a chronic tendency to assign causes to

structural factors, implicitly frame much Anglo-American sociology.26

But the tendency to concentrate on structural causal factors is also widespread elsewhere, such as in Bourdieus work, despite his recognition of the

potential causal efficacy of reflexive action at times (Bourdieu &

Wacquant, 1992, pp. 120 138).

In considerable part, this tendency represents the long effects of an

assumed but problematic dualism of structure and action in Western sociology. A similar tendency to locate causality at the structural level in

203

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

Bourdieus work work that aimed at displacing subjective objective binaries with that between the embodied and the relational shows that such

tendencies are reinforced by additional initial assumptions about the object

domain of the social sciences. Indeed, one key to revealing such additional

initial assumptions is a close analysis of the concepts agency and actor. As

we saw above, habitus enables us to frame agency in terms of an array of

dispositions that predominate in much of everyday life, particularly regarding routines. At the same time, Bourdieus tendency to downplay the causal

efficacy of reflexive action underscores that action itself needs to be further

conceptualized.

Recent neurology tells us that reflexive action is only about 10 percent

of agentic behavior (Montague & Berns, 2002). This needs to be placed in

context, though, for habitus with its institutional paradigms enables more

complex reflective action by enabling individuals to devote attention to

what they are doing in the sense of reflexively decided courses of behavior.

Thus, though (reflexive) actions may probabilistically only be roughly

10 percent of agentic behavior per se, certainly such actions are often

disproportionately important in reconstructing causal chains in human

history, to paraphrase the Authors Introduction to The Protestant Ethic.

Following from this, we also need to differentiate types of reflexive

action in terms of possible types of motivation. As mentioned above, the

problem of motivation is complex

as Weber recognized, motivations

can only be interpreted indirectly, taking behavior as evidence (1978,

pp. 8 14). The indirect identification of distinct types of motivation

follows from the fact that some intentional actions clearly involving deliberation are impossible to explain in terms of self-interested motivations, as

the behavior of the 19 individuals who hijacked jets and flew them into

buildings on September 11, 2001, in New York City and Washington, DC,

or the firefighters who began ascending the stairs in one of the burning

Twin Towers building only to be killed as the building collapsed on top of

them, demonstrates.27

In any case, we need to modify here Webers fourfold typology of

action

with its distinctions between purposive-instrumental, valuein light of

rational, traditional, and affective action (1978, pp. 24 26)

the discussion of agency and habitus above. First, we recognize that affective action is reflexive action motivated by the emotional influence of love,

affection, dislike, repugnance, hatred, and the like, as in Webers original

conception. Next, we rename purposive-instrumental action as strategic

action. This clarifies what such action entails as it assumes practical goals

in a strategic sense for persons considering them. Practical goals in a

204

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

strategic sense means here that strategic interests play predominant roles

steering social action, and thus practical concerns such as economic, political, and other such interests predominate in their motivation. Webers

concept of value-rational action, in contrast, is guided by non-immediate,

non-strategic, symbolic motivations, such as philosophical inclinations,

religious beliefs, scientific questioning, artistic proclivities, and the like.

And tensions between strategic and value-rational motivations have figured

centrally at key points in human history. [V]ery frequently the world

images that have been created by ideas have, like switchmen, determined

the tracks along which action has been pushed by the dynamics of interest

(Weber, 1946, p. 280).

This brings us to Webers problematic concept of traditional action,

which tends to collapse conscious adherence to a tradition and its orthodoxies with conventional behavior per se. The concepts of habitus and

institutional paradigm enable us to resolve Webers overburdened concept

of traditional action by shifting to both a broader conception of valuerational action, and bringing in the concept of habitus. Such a broader

range of value-rational action considers conscious, deliberative reflection in

favor of tradition an example of value-rational action, while simultaneously

identifying conventionalism with the realm of habitus and institutional

paradigms proper.28

From here, we can identify many additional subtypes and hybrid

motivations for reflexive action. Take what Erving Goffman (1959) called

dramaturgical action, and what Jeffrey Alexander (2010)

modifying

Goffman and developing an analysis of political action in the contemporary United States terms performative action. One can certainly question

the range that Goffman assigns to dramaturgical action in his 1959 text,

as Goffman himself does in the last pages. In contrast, performative

action as Alexander applies it to national presidential campaigns is finely

attuned to its subject matter. Indeed, performative action sits between

strategic and value-rational action along a continuum of types of reflexive

action.

The above indicates the problematic nature of trying to conceptualize all

sociologically relevant action as strategic action as Fligstein and McAdam

do, though the latter define this so broadly that it appears to overlap other

types of action.29 Are value-rational actions always strategic actions, for

instance? A related tendency in Fligstein and McAdam is to frame all fields

as strategic action fields along lines of incumbents and challengers, a

move that gives short shrift to beliefs and institutions, norms, and the

longue duree of customs and traditions in many social orders.30 All of this

205

The Developmental History of Human Social Practices

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

is bound up with absence of a sense of historicity in Fligstein and

McAdams proposed model of general social theory.

And indeed, the development of an adequate range of ideal types of

action for analyzing the range of human actions in history underscores the

need to reverse what Elias called sociologys retreat into the present

(1998). We turn to the application of one such action subtype dramaturgical action to actual skeins of social development in the section below on

explanatory narrative in order to illustrate the dynamic relation between

social analytics and explanatory narratives. For now, let us briefly note that

other aspects of human agency enabling types of actions require considerable conceptual development. Take, for instance, the social-psychological

concepts of personality and a wide suite of related concepts that help define

it, from cognition to consciousness, mind to the unconscious, and so on.

Indeed, personality entails a broad conception of the emergent properties

that make a person a person distinguished by a proper name with a specific

life history that identifies her or him.31

The analytic differentiation of anthrogeneric concepts and modes of

social practices offered above raises questions of how they enable formulation of models and causal hypotheses. Though the development of models

contributes to the analytic of society, in fact the formulation of these

models can most clearly be understood in relation to the formulation of

specific causal hypotheses regarding events in which human agency and

interaction are taken to be causally significant. This brings us to the topic

of explanatory narratives.

EXPLANATORY NARRATIVES

We now return to the proposition outlined at the beginning of this analysis,

namely, that most explanations in the social sciences should properly be

conceived as explanatory narratives. Explanatory narrative subordinates

the identification of causal factors to the reconstruction of a specific

enchainment of events in a historical process.32 Such explanatory narratives

grapple with the empirical problem of how to factor multiple experiential

perspectives of various agents into a broader narrative sequence focused on

key causal links in the chain of a historically irreducible sequence involving

the interaction of many people, as well as the unintended consequences of

such interaction. The multiple time-horizon problem [of many agents]

remains the central theoretical barrier to moving formalized narrative

206

MARC GARCELON

(C

)E

er

al

G

ro

up

Pu

bl

is

hi

ng

beyond the simple-minded analysis of stage processes and rational action

sequences. Serious institutional analysis cannot be conducted without

addressing it (Abbott, 1992, p. 441).

In order to do this, explanatory narrative subsumes a distinct model of

causal analysis, what Abbott calls the variables paradigm (1992). In this

currently predominant model of causal analysis in Western sociology,