Professional Documents

Culture Documents

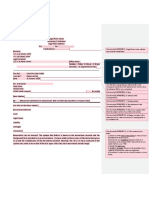

Court overturns decision fixing two-year period for street construction

Uploaded by

Terry FordOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Court overturns decision fixing two-year period for street construction

Uploaded by

Terry FordCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

L-22558

May 31, 1967

GREGORIO

ARANETA,

INC., petitioner,

vs.

THE PHILIPPINE SUGAR ESTATES DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD., respondent.

Araneta

and

Araneta

Rosauro Alvarez and Ernani Cruz Pao for respondent.

for

petitioner.

REYES, J.B.L., J.:

Petition for certiorari to review a judgment of the Court of Appeals, in its CA-G.R. No.

28249-R, affirming with modification, an amendatory decision of the Court of First

Instance of Manila, in its Civil Case No. 36303, entitled "Philippine Sugar Estates

Development Co., Ltd., plaintiff, versus J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc. and Gregorio Araneta,

Inc., defendants."

As found by the Court of Appeals, the facts of this case are:

J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc. is the owner of a big tract land situated in Quezon City,

otherwise known as the Sta. Mesa Heights Subdivision, and covered by a Torrens title

in its name. On July 28, 1950, through Gregorio Araneta, Inc., it (Tuason & Co.) sold a

portion thereof with an area of 43,034.4 square meters, more or less, for the sum of

P430,514.00, to Philippine Sugar Estates Development Co., Ltd. The parties stipulated,

among in the contract of purchase and sale with mortgage, that the buyer will

Build on the said parcel land the Sto. Domingo Church and Convent

while the seller for its part will

Construct streets on the NE and NW and SW sides of the land herein sold so

that the latter will be a block surrounded by streets on all four sides; and the

street on the NE side shall be named "Sto. Domingo Avenue;"

The buyer, Philippine Sugar Estates Development Co., Ltd., finished the construction of

Sto. Domingo Church and Convent, but the seller, Gregorio Araneta, Inc., which began

constructing the streets, is unable to finish the construction of the street in the Northeast

side named (Sto. Domingo Avenue) because a certain third-party, by the name of

Manuel Abundo, who has been physically occupying a middle part thereof, refused to

vacate the same; hence, on May 7, 1958, Philippine Sugar Estates Development Co.,

Lt. filed its complaint against J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc., and instance, seeking to compel

the latter to comply with their obligation, as stipulated in the above-mentioned deed of

sale, and/or to pay damages in the event they failed or refused to perform said

obligation.

Both defendants J. M. Tuason and Co. and Gregorio Araneta, Inc. answered the

complaint, the latter particularly setting up the principal defense that the action was

premature since its obligation to construct the streets in question was without a definite

period which needs to he fixed first by the court in a proper suit for that purpose before

a complaint for specific performance will prosper.

The issues having been joined, the lower court proceeded with the trial, and upon its

termination, it dismissed plaintiff's complaint (in a decision dated May 31, 1960),

upholding the defenses interposed by defendant Gregorio Araneta, Inc.1wph1.t

Plaintiff moved to reconsider and modify the above decision, praying that the court fix a

period within which defendants will comply with their obligation to construct the streets

in question.

Defendant Gregorio Araneta, Inc. opposed said motion, maintaining that plaintiff's

complaint did not expressly or impliedly allege and pray for the fixing of a period to

comply with its obligation and that the evidence presented at the trial was insufficient to

warrant the fixing of such a period.

On July 16, 1960, the lower court, after finding that "the proven facts precisely warrants

the fixing of such a period," issued an order granting plaintiff's motion for

reconsideration and amending the dispositive portion of the decision of May 31, 1960, to

read as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered giving defendant Gregorio Araneta,

Inc., a period of two (2) years from notice hereof, within which to comply with its

obligation under the contract, Annex "A".

Defendant Gregorio Araneta, Inc. presented a motion to reconsider the above quoted

order, which motion, plaintiff opposed.

On August 16, 1960, the lower court denied defendant Gregorio Araneta, Inc's. motion;

and the latter perfected its appeal Court of Appeals.

In said appellate court, defendant-appellant Gregorio Araneta, Inc. contended mainly

that the relief granted, i.e., fixing of a period, under the amendatory decision of July 16,

1960, was not justified by the pleadings and not supported by the facts submitted at the

trial of the case in the court below and that the relief granted in effect allowed a change

of theory after the submission of the case for decision.

Ruling on the above contention, the appellate court declared that the fixing of a period

was within the pleadings and that there was no true change of theory after the

submission of the case for decision since defendant-appellant Gregorio Araneta, Inc.

itself squarely placed said issue by alleging in paragraph 7 of the affirmative defenses

contained in its answer which reads

7. Under the Deed of Sale with Mortgage of July 28, 1950, herein defendant has

a reasonable time within which to comply with its obligations to construct and

complete the streets on the NE, NW and SW sides of the lot in question; that

under the circumstances, said reasonable time has not elapsed;

Disposing of the other issues raised by appellant which were ruled as not meritorious

and which are not decisive in the resolution of the legal issues posed in the instant

appeal before us, said appellate court rendered its decision dated December 27, 1963,

the dispositive part of which reads

IN VIEW WHEREOF, judgment affirmed and modified; as a consequence,

defendant is given two (2) years from the date of finality of this decision to

comply with the obligation to construct streets on the NE, NW and SW sides of

the land sold to plaintiff so that the same would be a block surrounded by streets

on all four sides.

Unsuccessful in having the above decision reconsidered, defendant-appellant Gregorio

Araneta, Inc. resorted to a petition for review by certiorari to this Court. We gave it due

course.

We agree with the petitioner that the decision of the Court of Appeals, affirming that of

the Court of First Instance is legally untenable. The fixing of a period by the courts

under Article 1197 of the Civil Code of the Philippines is sought to be justified on the

basis that petitioner (defendant below) placed the absence of a period in issue by

pleading in its answer that the contract with respondent Philippine Sugar Estates

Development Co., Ltd. gave petitioner Gregorio Araneta, Inc. "reasonable time within

which to comply with its obligation to construct and complete the streets." Neither of the

courts below seems to have noticed that, on the hypothesis stated, what the answer put

in issue was not whether the court should fix the time of performance, but whether or

not the parties agreed that the petitioner should have reasonable time to perform its part

of the bargain. If the contract so provided, then there was a period fixed, a "reasonable

time;" and all that the court should have done was to determine if that reasonable time

had already elapsed when suit was filed if it had passed, then the court should declare

that petitioner had breached the contract, as averred in the complaint, and fix the

resulting damages. On the other hand, if the reasonable time had not yet elapsed, the

court perforce was bound to dismiss the action for being premature. But in no case can

it be logically held that under the plea above quoted, the intervention of the court to fix

the period for performance was warranted, for Article 1197 is precisely predicated on the

absence of any period fixed by the parties.

Even on the assumption that the court should have found that no reasonable time or no

period at all had been fixed (and the trial court's amended decision nowhere declared

any such fact) still, the complaint not having sought that the Court should set a period,

the court could not proceed to do so unless the complaint in as first amended; for the

original decision is clear that the complaint proceeded on the theory that the period for

performance had already elapsed, that the contract had been breached and defendant

was already answerable in damages.

Granting, however, that it lay within the Court's power to fix the period of performance,

still the amended decision is defective in that no basis is stated to support the

conclusion that the period should be set at two years after finality of the judgment. The

list paragraph of Article 1197 is clear that the period can not be set arbitrarily. The law

expressly prescribes that

the Court shall determine such period as may under the circumstances been

probably contemplated by the parties.

All that the trial court's amended decision (Rec. on Appeal, p. 124) says in this respect

is that "the proven facts precisely warrant the fixing of such a period," a statement

manifestly insufficient to explain how the two period given to petitioner herein was

arrived at.

It must be recalled that Article 1197 of the Civil Code involves a two-step process. The

Court must first determine that "the obligation does not fix a period" (or that the period is

made to depend upon the will of the debtor)," but from the nature and the circumstances

it can be inferred that a period was intended" (Art. 1197, pars. 1 and 2). This preliminary

point settled, the Court must then proceed to the second step, and decide what period

was "probably contemplated by the parties" (Do., par. 3). So that, ultimately, the Court

can not fix a period merely because in its opinion it is or should be reasonable, but must

set the time that the parties are shown to have intended. As the record stands, the trial

Court appears to have pulled the two-year period set in its decision out of thin air, since

no circumstances are mentioned to support it. Plainly, this is not warranted by the Civil

Code.

In this connection, it is to be borne in mind that the contract shows that the parties were

fully aware that the land described therein was occupied by squatters, because the fact

is expressly mentioned therein (Rec. on Appeal, Petitioner's Appendix B, pp. 12-13). As

the parties must have known that they could not take the law into their own hands, but

must resort to legal processes in evicting the squatters, they must have realized that the

duration of the suits to be brought would not be under their control nor could the same

be determined in advance. The conclusion is thus forced that the parties must have

intended to defer the performance of the obligations under the contract until the

squatters were duly evicted, as contended by the petitioner Gregorio Araneta, Inc.

The Court of Appeals objected to this conclusion that it would render the date of

performance indefinite. Yet, the circumstances admit no other reasonable view; and this

very indefiniteness is what explains why the agreement did not specify any exact

periods or dates of performance.

It follows that there is no justification in law for the setting the date of performance at

any other time than that of the eviction of the squatters occupying the land in question;

and in not so holding, both the trial Court and the Court of Appeals committed reversible

error. It is not denied that the case against one of the squatters, Abundo, was still

pending in the Court of Appeals when its decision in this case was rendered.

In view of the foregoing, the decision appealed from is reversed, and the time for the

performance of the obligations of petitioner Gregorio Araneta, Inc. is hereby fixed at the

date that all the squatters on affected areas are finally evicted therefrom.

Costs against respondent Philippine Sugar Estates Development, Co., Ltd. So ordered.

Concepcion, C.J., Dizon, Regala, Makalintal, Bengzon, J.P., Sanchez and Castro, JJ.,

concur.

You might also like

- Completed Contract Review with 95% ScoreDocument14 pagesCompleted Contract Review with 95% Scorewootenr2002No ratings yet

- FACTS - Case Concenrning The Egart and The IbraDocument11 pagesFACTS - Case Concenrning The Egart and The IbraLolph Manila100% (1)

- Disciplinary Process 261118Document38 pagesDisciplinary Process 261118Foo Fang LeongNo ratings yet

- Scots Public Law ReadingsDocument5 pagesScots Public Law ReadingsElena100% (1)

- Digest SalesDocument16 pagesDigest Salesmailah awingNo ratings yet

- Payment Dispute Between Water Utility and Pipe SupplierDocument3 pagesPayment Dispute Between Water Utility and Pipe SupplierLois Eunice GabuyoNo ratings yet

- 19 Asiain v. JalandoniDocument1 page19 Asiain v. JalandoniJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- CivPro Tijam V SibonghanoyDocument2 pagesCivPro Tijam V SibonghanoyPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- Format of Opinion Writing Letter - FZ PDFDocument2 pagesFormat of Opinion Writing Letter - FZ PDFNiqian GoiNo ratings yet

- Panay Railways Inc., Vs Heva Management Development Corp., GR No. 154061 January 25, 2012 FactsDocument2 pagesPanay Railways Inc., Vs Heva Management Development Corp., GR No. 154061 January 25, 2012 FactsReena AlbanielNo ratings yet

- Excessive Bail Ruling OverturnedDocument18 pagesExcessive Bail Ruling OverturnedCaleb Josh PacanaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lizza Industries, Inc., Herbert Hochreiter, 775 F.2d 492, 2d Cir. (1985)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Lizza Industries, Inc., Herbert Hochreiter, 775 F.2d 492, 2d Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court On High Court's Suryanelli JudgmentDocument6 pagesSupreme Court On High Court's Suryanelli JudgmentPrem PanickerNo ratings yet

- Hao Vs Andres 2008Document13 pagesHao Vs Andres 2008Christiaan CastilloNo ratings yet

- Speedy Trial ActDocument8 pagesSpeedy Trial ActTheSupplier ShopNo ratings yet

- People vs. Tee, 395 SCRA 419, January 20, 2003Document3 pagesPeople vs. Tee, 395 SCRA 419, January 20, 2003Rizchelle Sampang-ManaogNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contract Assignment No.4 - Felibeth D. LingaDocument7 pagesObligations and Contract Assignment No.4 - Felibeth D. LingaFELIBETH LINGANo ratings yet

- Dormitorio V FernandezDocument8 pagesDormitorio V FernandezJansen OuanoNo ratings yet

- Cabarroguis vs. VicenteDocument3 pagesCabarroguis vs. VicentenurseibiangNo ratings yet

- Litonjua V LitonjuaDocument9 pagesLitonjua V LitonjuaHudson CeeNo ratings yet

- The Notaries Act, 1952Document6 pagesThe Notaries Act, 1952pitchiNo ratings yet

- SALES Remaining CasesDocument208 pagesSALES Remaining CasesJm CruzNo ratings yet

- Court upholds guilty verdict for frustrated murderDocument6 pagesCourt upholds guilty verdict for frustrated murderhowieboiNo ratings yet

- 02 Chittick Vs CADocument5 pages02 Chittick Vs CAArkhaye SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- Dimarucot V People-Due ProcessDocument2 pagesDimarucot V People-Due ProcessJenny A. BignayanNo ratings yet

- PNB vs. Philippine Vegetable Oil Company 49 Phil 897 FactsDocument2 pagesPNB vs. Philippine Vegetable Oil Company 49 Phil 897 FactsJay Mark EscondeNo ratings yet

- Chua vs. CaDocument3 pagesChua vs. CaANTHONY SALVADICONo ratings yet

- R65 R67Document43 pagesR65 R67Kent Wilson Orbase AndalesNo ratings yet

- Ben Mireku Vrs TettehDocument11 pagesBen Mireku Vrs TettehTimore Francis100% (1)

- VI. PERSONS SPECIFICALLY LIABLE - Persons Who Interfere With Contractual RelationsDocument4 pagesVI. PERSONS SPECIFICALLY LIABLE - Persons Who Interfere With Contractual RelationsJude Raphael S. FanilaNo ratings yet

- Ursua vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 112170, 10 April 1996, 256 SCRA 147 PDFDocument5 pagesUrsua vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 112170, 10 April 1996, 256 SCRA 147 PDFJoelz JoelNo ratings yet

- Mutuality of ContractsDocument19 pagesMutuality of ContractsChris InocencioNo ratings yet

- Sales 4 CasesDocument72 pagesSales 4 CasesShaiNo ratings yet

- 16 Acabal V AcabalDocument2 pages16 Acabal V AcabalpdasilvaNo ratings yet

- Chand Miah Vs Khodeza BibiDocument3 pagesChand Miah Vs Khodeza BibiALAMGIR ALAMGIRNo ratings yet

- Personal Determination by Judge - Examination of WitnessDocument58 pagesPersonal Determination by Judge - Examination of WitnessLen Vicente - FerrerNo ratings yet

- Sctions 8, 30 and 36 of The Revised Securities Act Do Not Require The Enactment of Implementing Rules To Make Them Binding and EffectiveDocument2 pagesSctions 8, 30 and 36 of The Revised Securities Act Do Not Require The Enactment of Implementing Rules To Make Them Binding and Effectiveambet amboyNo ratings yet

- Judge accused of improper bail grantDocument9 pagesJudge accused of improper bail grantXXXNo ratings yet

- 19 Casino JR V CaDocument11 pages19 Casino JR V CaPeachChioNo ratings yet

- Clinton V JonesDocument2 pagesClinton V Joneschappy_leigh118No ratings yet

- 2017 CorpoLaw - Course Calendar (As of Feb 06)Document10 pages2017 CorpoLaw - Course Calendar (As of Feb 06)Ace QuebalNo ratings yet

- OVERVIEW OF BASIS FOR RECOGNIZING FOREIGN JUDGMENTSDocument13 pagesOVERVIEW OF BASIS FOR RECOGNIZING FOREIGN JUDGMENTSrodrigo manluctaoNo ratings yet

- Republic v. CastellviDocument2 pagesRepublic v. CastellviJcNo ratings yet

- No Disbarment for Lawyer Who Acquired Client's Non-Litigated PropertyDocument2 pagesNo Disbarment for Lawyer Who Acquired Client's Non-Litigated Propertycatrina lobatonNo ratings yet

- RE An AdvocateDocument53 pagesRE An AdvocateHarshada SinghNo ratings yet

- Digest Pool 3rd Wave CIVPRODocument39 pagesDigest Pool 3rd Wave CIVPROErnest Talingdan CastroNo ratings yet

- Ben Line's appeal dismissalDocument26 pagesBen Line's appeal dismissalIshNo ratings yet

- 114489-2002-Bayas v. Sandiganbayan PDFDocument12 pages114489-2002-Bayas v. Sandiganbayan PDFSeok Gyeong KangNo ratings yet

- Bermudez Vs CastilloDocument4 pagesBermudez Vs Castillocmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank Vs CADocument6 pagesPhilippine National Bank Vs CAHamitaf LatipNo ratings yet

- HDMF vs. CADocument2 pagesHDMF vs. CARenzoSantosNo ratings yet

- Virgilio S. David, Petitioner, vs. Misamis Occidental II Electric Cooperative, Inc., Respondent.Document7 pagesVirgilio S. David, Petitioner, vs. Misamis Occidental II Electric Cooperative, Inc., Respondent.Kay AvilesNo ratings yet

- Intent to kill proven in frustrated homicide caseDocument4 pagesIntent to kill proven in frustrated homicide caseCharmaine MejiaNo ratings yet

- E. Que v. People, 154 SCRA 160: G.R. No. 75217-18Document36 pagesE. Que v. People, 154 SCRA 160: G.R. No. 75217-18Rolly HeridaNo ratings yet

- Tara Bano CaseDocument9 pagesTara Bano CaseaishvaryaNo ratings yet

- Commission) en Banc in SPA No. 13-254 (DC)Document8 pagesCommission) en Banc in SPA No. 13-254 (DC)lenvfNo ratings yet

- Rural Bank of Sta. Maria v. CA PDFDocument13 pagesRural Bank of Sta. Maria v. CA PDFSNo ratings yet

- Mercantile Law Bar Questions 2005-2012Document34 pagesMercantile Law Bar Questions 2005-2012panderbeerNo ratings yet

- 119-Iglesia Evangilica Metodista en Las Islas Filipinas (Iemelif) Et Al vs. Bishop Nathanael Lazaro Et Al G.R. No. 184088 July 6, 2010Document5 pages119-Iglesia Evangilica Metodista en Las Islas Filipinas (Iemelif) Et Al vs. Bishop Nathanael Lazaro Et Al G.R. No. 184088 July 6, 2010Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Araneta Inc. vs. Phil. Sugar EstatesDocument2 pagesAraneta Inc. vs. Phil. Sugar EstatesShielaMarie MalanoNo ratings yet

- 8 Araneta Vs PhilDocument8 pages8 Araneta Vs PhilEMNo ratings yet

- Araneta VS Phi Sugar EstateDocument6 pagesAraneta VS Phi Sugar EstateRichelle GraceNo ratings yet

- Court Has No Authority to Fix Period Where Contract Establishes "Reasonable TimeDocument5 pagesCourt Has No Authority to Fix Period Where Contract Establishes "Reasonable TimeXyrus BucaoNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds EYIS ownership of VESPA trademarkDocument21 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court upholds EYIS ownership of VESPA trademarkdenvergamlosenNo ratings yet

- Court upholds jurisdiction of environmental court over mining caseDocument6 pagesCourt upholds jurisdiction of environmental court over mining caseLenvicElicerLesiguesNo ratings yet

- Fredco Mfg. vs. Harvard College, 650 SCRA 232 (2011)Document13 pagesFredco Mfg. vs. Harvard College, 650 SCRA 232 (2011)Terry FordNo ratings yet

- Arce Sons & Company vs. SelectaDocument8 pagesArce Sons & Company vs. Selectashirlyn cuyongNo ratings yet

- Razon vs. TagitisDocument12 pagesRazon vs. TagitisTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Appeal Filed Out of Time Accepted Juris BonielDocument29 pagesAppeal Filed Out of Time Accepted Juris BonielTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Aquilina Araneta vs. CA and People (G.R. No. L-46638, July 9, 1986) PDFDocument6 pagesAquilina Araneta vs. CA and People (G.R. No. L-46638, July 9, 1986) PDFEcnerolAicnelavNo ratings yet

- Philip Morris vs. CA, 224 SCRA 576 (1993)Document14 pagesPhilip Morris vs. CA, 224 SCRA 576 (1993)Terry FordNo ratings yet

- Arellaga - Phil Telegraph V NLRC 80600Document4 pagesArellaga - Phil Telegraph V NLRC 80600Terry FordNo ratings yet

- ANTONIO ET AL Vs CA Negligence of FirmDocument2 pagesANTONIO ET AL Vs CA Negligence of FirmTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Almirol vs. RD Whetehr Documents Are Doubtful or FrivolousDocument4 pagesAlmirol vs. RD Whetehr Documents Are Doubtful or FrivolousTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Canlas vs. NapicoDocument4 pagesCanlas vs. NapicoTerry FordNo ratings yet

- CA Can Evaluate Teh Facts of Teh CaseDocument14 pagesCA Can Evaluate Teh Facts of Teh CaseTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Filing Fee of Pecuniary EstimatetionDocument42 pagesFiling Fee of Pecuniary EstimatetionTerry FordNo ratings yet

- ANTONIO ET AL Vs CA Negligence of FirmDocument2 pagesANTONIO ET AL Vs CA Negligence of FirmTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Castillo vs. CruzDocument10 pagesCastillo vs. CruzTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Resolution on Enforced Disappearance of Jonas BurgosDocument32 pagesSupreme Court Resolution on Enforced Disappearance of Jonas BurgosTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Carino Vs CarinoDocument6 pagesCarino Vs CarinokarlNo ratings yet

- Philippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceDocument90 pagesPhilippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Guardianship To Habeas Corpuz DigestsDocument39 pagesGuardianship To Habeas Corpuz DigestsTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Lee Vs IlaganDocument2 pagesLee Vs IlaganJorela TipanNo ratings yet

- Meralco vs. LimDocument6 pagesMeralco vs. LimTerry FordNo ratings yet

- 4.arigo VS Swift TubattahaDocument17 pages4.arigo VS Swift TubattahaVincent De VeraNo ratings yet

- Philippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceDocument90 pagesPhilippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Gsis Case DigestDocument2 pagesGsis Case Digestthelionleo1No ratings yet

- Philippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceDocument90 pagesPhilippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Azcona v. Jamandre lease contract cancellation requirementsDocument1 pageAzcona v. Jamandre lease contract cancellation requirementsTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Civil Law2 Digested 2016Document22 pagesCivil Law2 Digested 2016Terry FordNo ratings yet

- Digested 2016Document82 pagesDigested 2016Terry FordNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Case Digest on ObligationsDocument84 pagesCivil Law Case Digest on ObligationsTerry Ford100% (6)

- 168667-2013-Spouses Gaditano v. San Miguel Corp.Document6 pages168667-2013-Spouses Gaditano v. San Miguel Corp.Germaine CarreonNo ratings yet

- SPS Calo v Tan dispute over mining equipment loanDocument19 pagesSPS Calo v Tan dispute over mining equipment loanaljohn pantaleonNo ratings yet

- Secretary of Agrarian Reform vs. Tropical Homes, Inc., - DigestDocument3 pagesSecretary of Agrarian Reform vs. Tropical Homes, Inc., - DigestsherwinNo ratings yet

- OCA Circular No 62-2010Document3 pagesOCA Circular No 62-2010Chase DaclanNo ratings yet

- Memorandum On Behalf of The RespondentDocument43 pagesMemorandum On Behalf of The RespondentKabir Jaiswal50% (2)

- Cyber Space: Jurisdictional IssueDocument17 pagesCyber Space: Jurisdictional IssueAnand YadavNo ratings yet

- Swagman Hotels vs CA: Ruling on Curing Lack of Cause of ActionDocument9 pagesSwagman Hotels vs CA: Ruling on Curing Lack of Cause of ActionHenson MontalvoNo ratings yet

- ADRDocument25 pagesADRRAINBOW AVALANCHENo ratings yet

- CTA Erred in Ruling for Consignees in Customs Smuggling CaseDocument8 pagesCTA Erred in Ruling for Consignees in Customs Smuggling CasePopeyeNo ratings yet

- Stephen Lillo v. Darrell A. Bruhn, 11th Cir. (2011)Document3 pagesStephen Lillo v. Darrell A. Bruhn, 11th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Donald Greathouse v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company Director, Office of Workers' Compensation Programs, United States Department of Labor, 146 F.3d 224, 4th Cir. (1998)Document4 pagesDonald Greathouse v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company Director, Office of Workers' Compensation Programs, United States Department of Labor, 146 F.3d 224, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sandiganbayan jurisdiction over ill-gotten wealth casesDocument1 pageSandiganbayan jurisdiction over ill-gotten wealth casesDach S. CasipleNo ratings yet

- David v. MarquezDocument2 pagesDavid v. MarquezNathalia TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Torres V. Gonzales: Rnment (Has) Such Power Been IntrustedDocument50 pagesTorres V. Gonzales: Rnment (Has) Such Power Been IntrustedIlanieMalinisNo ratings yet

- Unlawful Detainer CasesDocument15 pagesUnlawful Detainer CasesKristine ComaNo ratings yet

- CB Resolution Annulment Sought Due to Lack of NoticeDocument4 pagesCB Resolution Annulment Sought Due to Lack of NoticeAngelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Power of Revenue CourtsDocument33 pagesPower of Revenue CourtsankitNo ratings yet

- George T. Chua vs. Judge Fortunito L. Madrona, Regional Trial Court, Branch 274, Parañaque CityDocument13 pagesGeorge T. Chua vs. Judge Fortunito L. Madrona, Regional Trial Court, Branch 274, Parañaque CityAnonymous dtceNuyIFI100% (1)

- Margate V RabacalDocument3 pagesMargate V RabacalNicoRecintoNo ratings yet

- Court rules on simulated land saleDocument6 pagesCourt rules on simulated land saleVeraNataaNo ratings yet

- Ching v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L-59731, January 11, 1990 (Supra.)Document3 pagesChing v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L-59731, January 11, 1990 (Supra.)Alan Vincent FontanosaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Decision on Judicial Foreclosure CaseDocument12 pagesSupreme Court Decision on Judicial Foreclosure CasebogoldoyNo ratings yet

- NPC must pay just compensation for property as of 1992 filing dateDocument2 pagesNPC must pay just compensation for property as of 1992 filing dateAnonymous UEyi81Gv100% (1)

- RFP For SAP System Audit and Related ActivitiesDocument56 pagesRFP For SAP System Audit and Related ActivitiesTapas Bhattacharya0% (1)

- Red V Coconut Products Vs CIR 17 SCRA 553 June 30,1966Document4 pagesRed V Coconut Products Vs CIR 17 SCRA 553 June 30,1966Mary Louise VillegasNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Ruling on Barangay Captain's RemovalDocument5 pagesSupreme Court Ruling on Barangay Captain's RemovalArkhaye SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- Appointment of Judges in IndiaDocument7 pagesAppointment of Judges in IndiaVaalu MuthuNo ratings yet