Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Intelligentia Et Scientia Semper Mea: Tax 2 Pinedapcgrnman

Uploaded by

Paul Christopher PinedaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Intelligentia Et Scientia Semper Mea: Tax 2 Pinedapcgrnman

Uploaded by

Paul Christopher PinedaCopyright:

Available Formats

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

VALUE ADDED TAX

1. NATURE OF VAT (SEC 105, NIRC)

SEC. 105. Persons Liable. - Any person who, in the course of trade or

business, sells barters, exchanges, leases goods or properties, renders

services, and any person who imports goods shall be subject to the

value-added tax (VAT) imposed in Sections 106 to 108 of this Code.

The value-added tax is an indirect tax and the amount of tax may be

shifted or passed on to the buyer, transferee or lessee of the goods,

properties or services. This rule shall likewise apply to existing

contracts of sale or lease of goods, properties or services at the time of

the effectivity of Republic Act No. 7716.

The phrase 'in the course of trade or business'means the regular

conduct or pursuit of a commercial or an economic activity, including

transactions incidental thereto, by any person regardless of whether or

not the person engaged therein is a nonstock, nonprofit private

organization (irrespective of the disposition of its net income and

whether or not it sells exclusively to members or their guests), or

government entity.

The rule of regularity, to the contrary notwithstanding, services as

defined in this Code rendered in the Philippines by nonresident foreign

persons shall be considered as being course of trade or business.

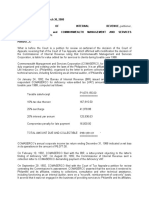

[G.R. No. 125355. March 30, 2000]

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. COURT

OF APPEALS and COMMONWEALTH MANAGEMENT AND

SERVICES CORPORATION,respondents. Court

DECISION

PARDO, J.:

What is before the Court is a petition for review on certiorari of the

decision of the Court of Appeals,[1] reversing that of the Court of Tax

Appeals,[2] which affirmed with modification the decision of the

Commissioner of Internal Revenue ruling that Commonwealth

Management and Services Corporation, is liable for value added tax for

services to clients during taxable year 1988.

Commonwealth

Management

and

Services

Corporation

(COMASERCO, for brevity), is a corporation duly organized and

existing under the laws of the Philippines. It is an affiliate of Philippine

American Life Insurance Co. (Philamlife), organized by the letter to

perform collection, consultative and other technical services, including

functioning as an internal auditor, of Philamlife and its other affiliates.

On January 24, 1992, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) issued an

assessment to private respondent COMASERCO for deficiency valueadded tax (VAT) amounting to P351,851.01, for taxable year 1988,

computed as follows:

"Taxable sale/receipt P1,679,155.00

10% tax due thereon 167,915.50

25% surcharge 41,978.88

20% interest per annum 125,936.63

Compromise penalty for late payment 16,000.00

TOTAL AMOUNT DUE AND COLLECTIBLE P 351,831.01"[3]

COMASERCO's annual corporate income tax return ending December

31, 1988 indicated a net loss in its operations in the amount of

P6,077.00. J lexj

On February 10, 1992, COMASERCO filed with the BIR, a letter-protest

objecting to the latter's finding of deficiency VAT. On August 20, 1992,

the Commissioner of Internal Revenue sent a collection letter to

COMASERCO demanding payment of the deficiency VAT.

On September 29,1992, COMASERCO filed with the Court of Tax

Appeals[4] a petition for review contesting the Commissioner's

assessment. COMASERCO asserted that the services it rendered to

Philamlife and its affiliates, relating to collections, consultative and

other technical assistance, including functioning as an internal auditor,

Page 1

TAX 2

were on a "no-profit, reimbursement-of-cost-only" basis. It averred that

it was not engaged id the business of providing services to Philamlife

and its affiliates. COMASERCO was established to ensure operational

orderliness and administrative efficiency of Philamlife and its affiliates,

and not in the sale of services. COMASERCO stressed that it was not

profit-motivated, thus not engaged in business. In fact, it did not

generate profit but suffered a net loss in taxable year 1988.

COMASERCO averred that since it was not engaged in business, it

was not liable to pay VAT.

On June 22, 1995, the Court of Tax Appeals rendered decision in favor

of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, the dispositive portion of

which reads:

"WHEREFORE, the decision of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue

assessing petitioner deficiency value-added tax for the taxable year

1988 is AFFIRMED with slight modifications. Accordingly, petitioner is

ordered to pay respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue the

amount of P335,831.01 inclusive of the 25% surcharge and interest

plus 20% interest from January 24, 1992 until fully paid pursuant to

Section 248 and 249 of the Tax Code.

"The compromise penalty of P16,000.00 imposed by the respondent in

her assessment letter shall not be included in the payment as there

was no compromise agreement entered into between petitioner and

respondent with respect to the value-added tax deficiency."[5]

On July 26, 1995, respondent filed with the Court of Appeals, petition

for review of the decision of the Court of Appeals.

After due proceedings, on May 13, 1996, the Court of Appeals rendered

decision reversing that of the Court of Tax Appeals, the dispositive

portion of which reads: Lexj uris

"WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, judgment is hereby rendered

REVERSING and SETTING ASIDE the questioned Decision

promulgated on 22 June 1995. The assessment for deficiency valueadded tax for the taxable year 1988 inclusive of surcharge, interest and

penalty charges are ordered CANCELLED for lack of legal and factual

basis."[6]

The Court of Appeals anchored its decision on the ratiocination in

another tax case involving the same parties, [7] where it was held that

COMASERCO was not liable to pay fixed and contractor's tax for

services rendered to Philamlife and its affiliates. The Court of Appeals,

in that case, reasoned that COMASERCO was not engaged in

business of providing services to Philamlife and its affiliates. In the

same manner, the Court of Appeals held that COMASERCO was not

liable to pay VAT for it was not engaged in the business of selling

services.

On July 16, 1996, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue filed with this

Court a petition for review on certiorari assailing the decision of the

Court of Appeals.

On August 7, 1996, we required respondent COMASERCO to file

comment on the petition, and on September 26, 1996, COMASERCO

complied with the resolution.[8]

We give due course to the petition.

At issue in this case is whether COMASERCO was engaged in the sale

of services, and thus liable to pay VAT thereon.

Petitioner avers that to "engage in business" and to "engage in the sale

of services" are two different things. Petitioner maintains that the

services rendered by COMASERCO to Philamlife and its affiliates, for a

fee or consideration, are subject to VAT. VAT is a tax on the value

added by the performance of the service. It is immaterial whether profit

is derived from rendering the service. Juri smis

We agree with the Commissioner.

Section 99 of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended

by Executive Order (E.O.) No. 273 in 1988, provides that:

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

"Section 99. Persons liable. - Any person who, in the course of trade

or business, sells, barters or exchanges goods, renders services, or

engages in similar transactions and any person who imports goods

shall be subject to the value-added tax (VAT) imposed in Sections 100

to 102 of this Code."[9]

COMASERCO contends that the term "in the course of trade or

business" requires that the "business" is carried on with a view to profit

or livelihood. It avers that the activities of the entity must be profitoriented. COMASERCO submits that it is not motivated by profit, as

defined by its primary purpose in the articles of incorporation, stating

that it is operating "only on reimbursement-of-cost basis, without any

profit." Private respondent argues that profit motive is material in

ascertaining who to tax for purposes of determining liability for VAT.

We disagree.

On May 28, 1994, Congress enacted Republic Act No. 7716, the

Expanded VAT Law (EVAT), amending among other sections, Section

99 of the Tax Code. On January 1, 1998, Republic Act 8424, the

National Internal Revenue Code of 1997, took effect. The amended law

provides that:

"SEC. 105. Persons Liable. - Any person who, in the course of trade or

business, sells, barters, exchanges, leases goods or properties,

renders services, and any person who imports goods shall be subject

to the value-added tax (VAT) imposed in Sections 106 and 108 of this

Code.

"The value-added tax is an indirect tax and the amount of tax may be

shifted or passed on to the buyer, transferee or lessee of the goods,

properties or services. This rule shall likewise apply to existing sale or

lease of goods, properties or services at the time of the effectivity of

Republic Act No.7716.

"The phrase "in the course of trade or business" means the regular

conduct or pursuit of a commercial or an economic activity, including

transactions incidental thereto, by any person regardless of whether or

not the person engaged therein is a nonstock, nonprofit organization

(irrespective of the disposition of its net income and whether or not it

sells exclusively to members of their guests), or government entity. Jjj

uris

"The rule of regularity, to the contrary notwithstanding, services as

defined in this Code rendered in the Philippines by nonresident foreign

persons shall be considered as being rendered in the course of trade or

business."

Contrary to COMASERCO's contention the above provision clarifies

that even a non-stock, non-profit, organization or government entity, is

liable to pay VAT on the sale of goods or services. VAT is a tax on

transactions, imposed at every stage of the distribution process on the

sale, barter, exchange of goods or property, and on the performance of

services, even in the absence of profit attributable thereto. The term "in

the course of trade or business" requires the regular conduct or pursuit

of a commercial or an economic activity, regardless of whether or not

the entity is profit-oriented.

The definition of the term "in the course of trade or business"

incorporated in the present law applies to all transactions even to those

made prior to its enactment. Executive Order No. 273 stated that any

person who, in the course of trade or business, sells, barters or

exchanges goods and services, was already liable to pay VAT. The

present law merely stresses that even a nonstock, nonprofit

organization or government entity is liable to pay VAT for the sale of

goods and services.

Section 108 of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997[10] defines

the phrase "sale of services" as the "performance of all kinds of

services for others for a fee, remuneration or consideration." It includes

"the supply of technical advice, assistance or services rendered in

Page 2

TAX 2

connection with technical management or administration of any

scientific, industrial or commercial undertaking or project."[11]

On February 5, 1998, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue issued

BIR Ruling No. 010-98[12] emphasizing that a domestic corporation that

provided technical, research, management and technical assistance to

its affiliated companies and received payments on a reimbursement-ofcost basis, without any intention of realizing profit, was subject to VAT

on services rendered. In fact, even if such corporation was organized

without any intention of realizing profit, any income or profit generated

by the entity in the conduct of its activities was subject to income tax.lex

Hence, it is immaterial whether the primary purpose of a corporation

indicates that it receives payments for services rendered to its affiliates

on a reimbursement-on-cost basis only, without realizing profit, for

purposes of determining liability for VAT on services rendered. As long

as the entity provides service for a fee, remuneration or consideration,

then the service rendered is subject to VAT.

At any rate, it is a rule that because taxes are the lifeblood of the

nation, statutes that allow exemptions are construed strictly against the

grantee and liberally in favor of the government. Otherwise stated, any

exemption from the payment of a tax must be clearly stated in the

language of the law; it cannot be merely implied therefrom. [13] In the

case of VAT, Section 109, Republic Act 8424 clearly enumerates the

transactions exempted from VAT. The services rendered by

COMASERCO do not fall within the exemptions.

Both the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and the Court of Tax

Appeals correctly ruled that the services rendered by COMASERCO to

Philamlife and its affiliates are subject to VAT. As pointed out by the

Commissioner, the performance of all kinds of services for others for a

fee, remuneration or consideration is considered as sale of services

subject to VAT. As the government agency charged with the

enforcement of the law, the opinion of the Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, in the absence of any showing that it is plainly wrong, is

entitled to great weight.[14] Also, it has been the long standing policy and

practice of this Court to respect the conclusions of quasi-judicial

agencies, such as the Court of Tax Appeals which, by the nature of its

functions, is dedicated exclusively to the study and consideration of tax

cases and has necessarily developed an expertise on the subject,

unless there has been an abuse or improvident exercise of its authority.

[15]

There is no merit to respondent's contention that the Court of Appeals'

decision in CA-G. R. No. 34042, declaring the COMASERCO as not

engaged in business and not liable for the payment of fixed and

percentage taxes, binds petitioner. The issue in CA-G. R. No. 34042 is

different from the present case, which involves COMASERCO's liability

for VAT. As heretofore stated, every person who sells, barters, or

exchanges goods and services, in the course of trade or business, as

defined by law, is subject to VAT. Jksm

WHEREFORE, the Court GRANTS the petition and REVERSES the

decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G. R. SP No. 37930. The Court

hereby REINSTATES the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals in C. T.

A. Case No. 4853.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

G.R. No. 146984.July 28, 2006.*

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs.

MAGSAYSAY LINES, INC., BALIWAG NAVIGATION, INC., FIM

LIMITED OF THE MARDEN GROUP (HK) and NATIONAL

DEVELOPMENT COMPANY, respondents.

Taxation; Value Added Tax (VAT); Value Added Tax (VAT) is

ultimately a tax on consumption, even though it is assessed on

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

many levels of transactions on the basis of a fixed percentage.A

brief reiteration of the basic principles governing VAT is in order.

VAT is ultimately a tax on consumption, even though it is

assessed on many levels of transactions on the basis of a fixed

percentage. It is the end user of consumer goods or services

which ultimately shoulders the tax, as the liability therefrom is

passed on to the end users by the providers of these goods or

services who in turn may credit their own VAT liability (or input

VAT) from the VAT payments they receive from the final consumer

(or output VAT).

Value Added Tax (VAT); The tax is levied only on the sale, barter or

exchange of goods or services by persons who engage in such

activities in the course of trade or business.VAT is not a

singular-minded tax on every transactional level. Its assessment

bears direct relevance to the taxpayers role or link in the

production chain. Hence, as affirmed by Section 99 of the Tax

Code and its subsequent incarnations, the tax is levied only on

the sale, barter or exchange of goods or services by persons who

engage in such activities, in the course of trade or business.

These transactions outside the course of trade or business may

invariably contribute to the production chain, but they do so only

as a matter of accident or incident. As the sales of goods or

services do not occur within the course of trade or business, the

providers of such goods or services would hardly, if at all, have

the opportunity to appropriately credit any VAT liability as against

their own accumulated VAT collections since the accumulation of

output VAT arises in the first place only through the ordinary

course of trade or business.

Same; Any sale, barter or exchange of goods or services not in

the course of trade or business is not subject to Value Added Tax

(VAT).The conclusion that the sale was not in the course of

trade or business, which the CIR does not dispute before this

Court, should have definitively settled the matter. Any sale, barter

or exchange of goods or services not in the course of trade or

business is not subject to VAT.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

The Solicitor General for petitioner.

Office of the Government Corporate Counsel for NDC.

Ma. Valentina S. Santana-Cruz for respondent Magsaysay Lines.

TINGA,J.:

The issue in this present petition is whether the sale by the National

Development Company (NDC) of five (5) of its vessels to the private

respondents is subject to value-added tax (VAT) under the National

Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (Tax Code) then prevailing at the time

of the sale. The Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) and the Court of Appeals

commonly ruled that the sale is not subject to VAT. We affirm, though

on a more unequivocal rationale than that utilized by the rulings under

review. The fact that the sale was not in the course of the trade or

business of NDC is sufficient in itself to declare the sale as outside the

coverage of VAT.

The facts are culled primarily from the ruling of the CTA.

Pursuant to a government program of privatization, NDC decided to sell

to private enterprise all of its shares in its wholly-owned subsidiary the

National Marine Corporation (NMC). The NDC decided to sell in one lot

its NMC shares and five (5) of its ships, which are 3,700 DWT TweenDecker, Kloeckner type vessels.1 The vessels were constructed for

the NDC between 1981 and 1984, then initially leased to Luzon

Stevedoring Company, also its wholly-owned subsidiary. Subsequently,

Page 3

TAX 2

the vessels were transferred and leased, on a bareboat basis, to the

NMC.2

The NMC shares and the vessels were offered for public bidding.

Among the stipulated terms and conditions for the public auction was

that the winning bidder was to pay a value added tax of 10% on the

value of the vessels.3 On 3 June 1988, private respondent Magsaysay

Lines, Inc. (Magsaysay Lines) offered to buy the shares and the

vessels for P168,000,000.00. The bid was made by Magsaysay Lines,

purportedly for a new company still to be formed composed of itself,

Baliwag Navigation, Inc., and FIM Limited of the Marden Group based

in Hongkong (collectively, private respondents).4 The bid was approved

by the Committee on Privatization, and a Notice of Award dated 1 July

1988 was issued to Magsaysay Lines.

On 28 September 1988, the implementing Contract of Sale was

executed between NDC, on one hand, and Magsaysay Lines, Baliwag

Navigation, and FIM Limited, on the other. Paragraph 11.02 of the

contract stipulated that [v]alue-added tax, if any, shall be for the

account of the PURCHASER.5 Per arrangement, an irrevocable

confirmed Letter of Credit previously filed as bidders bond was

accepted by NDC as security for the payment of VAT, if any. By this

time, a formal request for a ruling on whether or not the sale of the

vessels was subject to VAT had already been filed with the Bureau of

Internal Revenue (BIR) by the law firm of Sycip Salazar Hernandez &

Gatmaitan, presumably in behalf of private respondents. Thus, the

parties agreed that should no favorable ruling be received from the BIR,

NDC was authorized to draw on the Letter of Credit upon written

demand the amount needed for the payment of the VAT on the

stipulated due date, 20 December 1988.6

In January of 1989, private respondents through counsel received VAT

Ruling No. 568-88 dated 14 December 1988 from the BIR, holding that

the sale of the vessels was subject to the 10% VAT. The ruling cited the

fact that NDC was a VAT-registered enterprise, and thus its

transactions incident to its normal VAT registered activity of leasing out

personal property including sale of its own assets that are movable,

tangible objects which are appropriable or transferable are subject to

the 10% [VAT].7

Private respondents moved for the reconsideration of VAT Ruling No.

568-88, as well as VAT Ruling No. 395-88 (dated 18 August 1988),

which made a similar ruling on the sale of the same vessels in

response to an inquiry from the Chairman of the Senate Blue Ribbon

Committee. Their motion was denied when the BIR issued VAT Ruling

Nos. 007-89 dated 24 February 1989, reiterating the earlier VAT rulings.

At this point, NDC drew on the Letter of Credit to pay for the VAT, and

the amount of P15,120,000.00 in taxes was paid on 16 March 1989.

On 10 April 1989, private respondents filed an Appeal and Petition for

Refund with the CTA, followed by a Supplemental Petition for Review

on 14 July 1989. They prayed for the reversal of VAT Rulings No. 39588, 568-88 and 007-89, as well as the refund of the VAT payment made

amounting to P15,120,000.00.8 The Commissioner of Internal Revenue

(CIR) opposed the petition, first arguing that private respondents were

not the real parties in interest as they were not the transferors or sellers

as contemplated in Sections 99 and 100 of the then Tax Code. The CIR

also squarely defended the VAT rulings holding the sale of the vessels

liable for VAT, especially citing Section 3 of Revenue Regulation No. 587 (R.R. No. 5-87), which provided that [VAT] is imposed on any sale

or transactions deemed sale of taxable goods (including capital goods,

irrespective of the date of acquisition). The CIR argued that the sale of

the vessels were among those transactions deemed sale, as

enumerated in Section 4 of R.R. No. 5-87. It seems that the CIR

particularly emphasized Section 4(E)(i) of the Regulation, which

classified change of ownership of business as a circumstance that

gave rise to a transaction deemed sale.

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

In a Decision dated 27 April 1992, the CTA rejected the CIRs

arguments and granted the petition.9 The CTA ruled that the sale of a

vessel was an isolated transaction, not done in the ordinary course of

NDCs business, and was thus not subject to VAT, which under Section

99 of the Tax Code, was applied only to sales in the course of trade or

business. The CTA further held that the sale of the vessels could not be

deemed sale, and thus subject to VAT, as the transaction did not fall

under the enumeration of transactions deemed sale as listed either in

Section 100(b) of the Tax Code, or Section 4 of R.R. No. 5-87. Finally,

the CTA ruled that any case of doubt should be resolved in favor of

private respondents since Section 99 of the Tax Code which

implemented VAT is not an exemption provision, but a classification

provision which warranted the resolution of doubts in favor of the

taxpayer.

The CIR appealed the CTA Decision to the Court of Appeals,10 which

on 11 March 1997, rendered a Decision reversing the CTA.11 While the

appellate court agreed that the sale was an isolated transaction, not

made in the course of NDCs regular trade or business, it nonetheless

found that the transaction fell within the classification of those deemed

sale under R.R. No. 5-87, since the sale of the vessels together with

the NMC shares brought about a change of ownership in NMC. The

Court of Appeals also applied the principle governing tax exemptions

that such should be strictly construed against the taxpayer, and liberally

in favor of the government.12

However, the Court of Appeals reversed itself upon reconsidering the

case, through a Resolution dated 5 February 2001.13 This time, the

appellate court ruled that the change of ownership of business as

contemplated in R.R. No. 5-87 must be a consequence of the

retirement from or cessation of business by the owner of the goods,

as provided for in Section 100 of the Tax Code. The Court of Appeals

also agreed with the CTA that the classification of transactions deemed

sale was a classification statute, and not an exemption statute, thus

warranting the resolution of any doubt in favor of the taxpayer.

To the mind of the Court, the arguments raised in the present petition

have already been adequately discussed and refuted in the rulings

assailed before us. Evidently, the petition should be denied. Yet the

Court finds that Section 99 of the Tax Code is sufficient reason for

upholding the refund of VAT payments, and the subsequent

disquisitions by the lower courts on the applicability of Section 100 of

the Tax Code and Section 4 of R.R. No. 5-87 are ultimately irrelevant.

A brief reiteration of the basic principles governing VAT is in order. VAT

is ultimately a tax on consumption, even though it is assessed on many

levels of transactions on the basis of a fixed percentage.15 It is the end

user of consumer goods or services which ultimately shoulders the tax,

as the liability therefrom is passed on to the end users by the providers

of these goods or services16 who in turn may credit their own VAT

liability (or input VAT) from the VAT payments they receive from the

final consumer (or output VAT).17 The final purchase by the end

consumer represents the final link in a production chain that itself

involves several transactions and several acts of consumption. The

VAT system assures fiscal adequacy through the collection of taxes on

every level of consumption,18 yet assuages the manufacturers or

providers of goods and services by enabling them to pass on their

respective VAT liabilities to the next link of the chain until finally the end

consumer shoulders the entire tax liability.

Yet VAT is not a singular-minded tax on every transactional level. Its

assessment bears direct relevance to the taxpayers role or link in the

production chain. Hence, as affirmed by Section 99 of the Tax Code

and its subsequent incarnations,19 the tax is levied only on the sale,

barter or exchange of goods or services by persons who engage in

such activities, in the course of trade or business. These transactions

outside the course of trade or business may invariably contribute to the

Page 4

TAX 2

production chain, but they do so only as a matter of accident or

incident. As the sales of goods or services do not occur within the

course of trade or business, the providers of such goods or services

would hardly, if at all, have the opportunity to appropriately credit any

VAT liability as against their own accumulated VAT collections since the

accumulation of output VAT arises in the first place only through the

ordinary course of trade or business.

That the sale of the vessels was not in the ordinary course of trade or

business of NDC was appreciated by both the CTA and the Court of

Appeals, the latter doing so even in its first decision which it eventually

reconsidered.20 We cite with approval the CTAs explanation on this

point:

In Imperial v. Collector of Internal Revenue, G.R. No. L-7924,

September 30, 1955 (97 Phil. 992), the term carrying on business

does not mean the performance of a single disconnected act, but

means conducting, prosecuting and continuing business by performing

progressively all the acts normally incident thereof; while doing

business conveys the idea of business being done, not from time to

time, but all the time. [J. Aranas, UPDATED NATIONAL INTERNAL

REVENUE CODE (WITH ANNOTATIONS), p. 608-9 (1988)]. Course of

business is what is usually done in the management of trade or

business. [Idmi v. Weeks & Russel, 99 So. 761, 764, 135 Miss. 65,

cited in Words & Phrases, Vol. 10, (1984)]

What is clear therefore, based on the aforecited jurisprudence, is that

course of business or doing business connotes regularity of activity.

In the instant case, the sale was an isolated transaction. The sale

which was involuntary and made pursuant to the declared policy of

Government for privatization could no longer be repeated or carried on

with regularity. It should be emphasized that the normal VAT-registered

activity of NDC is leasing personal property.21

This finding is confirmed by the Revised Charter22 of the NDC which

bears no indication that the NDC was created for the primary purpose

of selling real property.23

The conclusion that the sale was not in the course of trade or business,

which the CIR does not dispute before this Court,24 should have

definitively settled the matter. Any sale, barter or exchange of goods or

services not in the course of trade or business is not subject to VAT.

Section 100 of the Tax Code, which is implemented by Section 4(E)(i)

of R.R. No. 5-87 now relied upon by the CIR, is captioned Value-added

tax on sale of goods, and it expressly states that [t]here shall be

levied, assessed and collected on every sale, barter or exchange of

goods, a value added tax x x x. Section 100 should be read in light of

Section 99, which lays down the general rule on which persons are

liable for VAT in the first place and on what transaction if at all. It may

even be noted that Section 99 is the very first provision in Title IV of the

Tax Code, the Title that covers VAT in the law. Before any portion of

Section 100, or the rest of the law for that matter, may be applied in

order to subject a transaction to VAT, it must first be satisfied that the

taxpayer and transaction involved is liable for VAT in the first place

under Section 99.

It would have been a different matter if Section 100 purported to define

the phrase in the course of trade or business as expressed in Section

99. If that were so, reference to Section 100 would have been

necessary as a means of ascertaining whether the sale of the vessels

was in the course of trade or business, and thus subject to VAT. But

that is not the case. What Section 100 and Section 4(E)(i) of R.R. No.

5-87 elaborate on is not the meaning of in the course of trade or

business, but instead the identification of the transactions which may

be deemed as sale. It would become necessary to ascertain whether

under those two provisions the transaction may be deemed a sale, only

if it is settled that the transaction occurred in the course of trade or

business in the first place. If the transaction transpired outside the

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

course of trade or business, it would be irrelevant for the purpose of

determining VAT liability whether the transaction may be deemed sale,

since it anyway is not subject to VAT.

Accordingly, the Court rules that given the undisputed finding that the

transaction in question was not made in the course of trade or business

of the seller, NDC that is, the sale is not subject to VAT pursuant to

Section 99 of the Tax Code, no matter how the said sale may hew to

those transactions deemed sale as defined under Section 100.

In any event, even if Section 100 or Section 4 of R.R. No. 5-87 were to

find application in this case, the Court finds the discussions offered on

this point by the CTA and the Court of Appeals (in its subsequent

Resolution) essentially correct. Section 4 (E)(i) of R.R. No. 5-87 does

classify as among the transactions deemed sale those involving

change of ownership of business. However, Section 4(E) of R.R. No.

5-87, reflecting Section 100 of the Tax Code, clarifies that such change

of ownership is only an attending circumstance to retirement from or

cessation of business[,] with respect to all goods on hand [as] of the

date of such retirement or cessation.25 Indeed, Section 4(E) of R.R.

No. 5-87 expressly characterizes the change of ownership of

business as only a circumstance that attends those transactions

deemed sale, which are otherwise stated in the same section.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Quisumbing (Chairperson), Carpio, Carpio-Morales and Velasco, Jr.,

JJ., concur.

Petition denied.

Note.Petitioner is not the proper party to claim such VAT refund.

(Contex Corporation vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 433 SCRA

376 [2004])

G.R. Nos. 134587 & 134588. July 8, 2005.*

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE,

BENGUET CORPORATION, respondent.\

petitioner, vs.

Taxation; Rulings, circulars, rules and regulations promulgated by

the Commissioner of Internal Revenue would have no retroactive

application if to so apply them would be prejudicial to the

taxpayers.In a long line of cases, this Court has affirmed that

the rulings, circular, rules and regulations promulgated by the

Commissioner of Internal Revenue would have no retroactive

application if to so apply them would be prejudicial to the

taxpayers. In fact, both petitioner and respondent agree that the

retroactive application of VAT Ruling No. 008-92 is valid only if

such application would not be prejudicial to the respondent

pursuant to the explicit mandate under Sec. 246 of the NIRC, thus:

Sec. 246. Non-retroactivity of rulings.Any revocation,

modification or reversal of any of the rules and regulations

promulgated in accordance with the preceding Section or any of

the rulings or circulars promulgated by the Commissioner shall

not be given retroactive application if the revocation, modification

or reversal will be prejudicial to the taxpayers except in the

following cases: (a) where the taxpayer deliberately misstates or

omits material facts from his return on any document required of

him by the Bureau of Internal Revenue; (b) where the facts

subsequently gathered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue are

materially different form the facts on which the ruling is based; or

(c) where the taxpayer acted in bad faith.

Same; Appeals; The determination of whether a taxpayer had

suffered prejudice is a factual issue.To begin with, the

determination of whether respondent had suffered prejudice is a

Page 5

TAX 2

factual issue. It is an established rule that in the exercise of its

power of review, the Supreme Court is not a trier of facts.

Moreover, in the exercise of the Supreme Courts power of review,

the findings of facts of the Court of Appeals are conclusive and

binding on the Supreme Court. An exception to this rule is when

the findings of fact a quo are conflicting, as is in this case.

Same; Value Added Tax (VAT); Words and Phrases; VAT is a

percentage tax imposed at every stage of the distribution process

on the sale, barter, exchange or lease of goods or properties and

rendition of services in the course of trade or business, or the

importation of goodsit is an indirect tax which may be shifted to

the buyer, transferee, or lessee of the goods, properties, or

services but the party directly liable for the payment of the tax is

the seller; Transactions which are taxed at zero-rate do not result

in any output tax; Input VAT attributable to zero-rated sales could

be refunded or credited against other internal revenue taxes at the

option of the taxpayer.VAT is a percentage tax imposed at every

stage of the distribution process on the sale, barter, exchange or

lease of goods or properties and rendition of services in the

course of trade or business, or the importation of goods. It is an

indirect tax, which may be shifted to the buyer, transferee, or

lessee of the goods, properties, or services. However, the party

directly liable for the payment of the tax is the seller. In

transactions taxed at a 10% rate, when at the end of any given

taxable quarter the output VAT exceeds the input VAT, the excess

shall be paid to the government; when the input VAT exceeds the

output VAT, the excess would be carried over to VAT liabilities for

the succeeding quarter or quarters. On the other hand,

transactions which are taxed at zero-rate do not result in any

output tax. Input VAT attributable to zero-rated sales could be

refunded or credited against other internal revenue taxes at the

option of the taxpayer.

Same; Same; In the instant case, the retroactive application of

VAT Ruling No. 008-92 unilaterally forfeited or withdrew the option

of the seller to pass on its VAT costs to the Central Bank, with the

adverse effect that said seller became the unexpected and

unwilling debtor to the BIR of the amount equivalent to the total

VAT cost of its product, a liability it previously could have

recovered from the BIR in a zero-rated scenario or at least passed

on to the Central Bank had it known it would have been taxed at a

10% rate.There appears to be no upfront economic difference in

changing the sale of gold to the Central Bank from a 0% to 10%

VAT rate provided that respondent would be allowed the choice to

pass on its VAT costs to the Central Bank. In the instant case, the

retroactive application of VAT Ruling No. 008-92 unilaterally

forfeited or withdrew this option of respondent. The adverse effect

is that respondent became the unexpected and unwilling debtor to

the BIR of the amount equivalent to the total VAT cost of its

product, a liability it previously could have recovered from the BIR

in a zero-rated scenario or at least passed on to the Central Bank

had it known it would have been taxed at a 10% rate. Thus, it is

clear that respondent suffered economic prejudice when its

consummated sales of gold to the Central Bank were taken out of

the zero-rated category. The change in the VAT rating of

respondents transactions with the Central Bank resulted in the

twin loss of its exemption from payment of output VAT and its

opportunity to recover input VAT, and at the same time subjected

it to the 10% VAT sans the option to pass on this cost to the

Central Bank, with the total prejudice in money terms being

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

equivalent to the 10% VAT levied on its sales of gold to the Central

Bank.

Same; Same; The prejudice experienced by the seller lies in the

fact that the tax refunds/credits that it expected to receive had

effectively disappeared by virtue of its newfound output VAT

liability against which the Commissioner of Internal Revenue had

offset the expected refund/credit; What use would a credit be

where there is nothing to set it off against?On petitioners first

suggested recoupment modality, respondent counters that its

other sales subject to 10% VAT are so minimal that this mode is of

little value. Indeed, what use would a credit be where there is

nothing to set it off against? Moreover, respondent points out that

after having been imposed with 10% VAT sans the opportunity to

pass on the same to the Central Bank, it was issued a deficiency

tax assessment because its input VAT tax credits were not enough

to offset the retroactive 10% output VAT. The prejudice then

experienced by respondent lies in the fact that the tax

refunds/credits that it expected to receive had effectively

disappeared by virtue of its newfound output VAT liability against

which petitioner had offset the expected refund/credit.

Additionally, the prejudice to respondent would not simply

disappear, as petitioner claims, when a liability (which liability was

not there to begin with) is imposed concurrently with an

opportunity to reduce, not totally eradicate, the newfound liability.

In sum, contrary to petitioners suggestion, respondents net

income still decreased corresponding to the amount it expected

as its refunds/ credits and the deficiency assessments against it,

which when summed up would be the total cost of the 10%

retroactive VAT levied on respondent.

Same; Same; Tax Refunds; The burden of having to go through an

unnecessary and cumbersome refund process is prejudice

enough.This leads us to the second recourse that petitioner has

suggested to offset any resulting prejudice to respondent as a

consequence of giving retroactive effect to BIR VAT Ruling No.

008-92. Petitioner submits that granting that respondent has no

other sale subject to 10% VAT against which its input taxes may

be used in payment, then respondent is constituted as the final

entity against which the costs of the tax passes-on shall legally

stop; hence, the input taxes may be converted as costs available

as deduction for income tax purposes. Even assuming that the

right to recover respondents excess payment of income tax has

not yet prescribed, this relief would only address respondents

overpayment of income tax but not the other burdens discussed

above. Verily, this remedy is not a feasible option for respondent

because the very reason why it was issued a deficiency tax

assessment is that its input VAT was not enough to offset its

retroactive output VAT. Indeed, the burden of having to go through

an unnecessary and cumbersome refund process is prejudice

enough. Moreover, there is in fact nothing left to claim as a

deduction from income taxes. From the foregoing it is clear that

petitioners suggested options by which prejudice would be

eliminated from a retroactive application of VAT Ruling No. 008-92

are either simply inadequate or grossly unrealistic.

Same; Same; Estoppel; While it is true that government is not

estopped from collecting taxes which remain unpaid on account

of the errors or mistakes of its agents and/or officials and there

could be no vested right arising from an erroneous interpretation

of law, these principles must give way to exceptions based on and

in keeping with the interest of justice and fairplay.At the time

Page 6

TAX 2

when the subject transactions were consummated, the prevailing

BIR regulations relied upon by respondent ordained that gold

sales to the Central Bank were zero-rated. The BIR interpreted

Sec. 100 of the NIRC in relation to Sec. 2 of E.O. No. 581 s. 1980

which prescribed that gold sold to the Central Bank shall be

considered export and therefore shall be subject to the export and

premium duties. In coming out with this interpretation, the BIR

also considered Sec. 169 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 which

states that all sales of gold to the Central Bank are considered

constructive exports. Respondent should not be faulted for

relying on the BIRs interpretation of the said laws and

regulations. While it is true, as petitioner alleges, that government

is not estopped from collecting taxes which remain unpaid on

account of the errors or mistakes of its agents and/or officials and

there could be no vested right arising from an erroneous

interpretation of law, these principles must give way to exceptions

based on and in keeping with the interest of justice and fairplay,

as has been done in the instant matter. For, it is primordial that

every person must, in the exercise of his rights and in the

performance of his duties, act with justice, give everyone his due,

and observe honesty and good faith.

Same; Same; The taxpayer in this case has been put on the

receiving end of a grossly unfair deal, the sort of unjust treatment

which the law in Sec. 249 of the National Internal Revenue Code

abhors and forbids.Respondent, in this case, has similarly been

put on the receiving end of a grossly unfair deal. Before

respondent was entitled to tax refunds or credits based on

petitioners own issuances. Then suddenly, it found itself instead

being made to pay deficiency taxes with petitioners retroactive

change in the VAT categorization of respondents transactions

with the Central Bank. This is the sort of unjust treatment of a

taxpayer which the law in Sec. 246 of the NIRC abhors and

forbids.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Romulo, Mabanta, Buenaventura, Sayoc & Delos Angeles for

respondent.

TINGA, J.:

This is a petition for the review of a consolidated Decision of the

Former Fourteenth Division of the Court of Appeals1 ordering the

Commissioner of Internal Revenue to award tax credits to Benguet

Corporation in the amount corresponding to the input value added

taxes that the latter had incurred in relation to its sale of gold to the

Central Bank during the period of 01 August 1989 to 31 July 1991.

Petitioner is the Commissioner of Internal Revenue (petitioner) acting

in his official capacity as head of the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR),

an attached agency of the Department of Finance,2 with the authority,

inter alia, to determine claims for refunds or tax credits as provided by

law.3

Respondent Benguet Corporation (respondent) is a domestic

corporation organized and existing by virtue of Philippine laws,

engaged in the exploration, development and operation of mineral

resources, and the sale or marketing thereof to various entities.4

Respondent is a value added tax (VAT) registered enterprise.5

The transactions in question occurred during the period between 1988

and 1991. Under Sec. 99 of the National Internal Revenue Code

(NIRC),6 as amended by Executive Order (E.O.) No. 273 s. 1987, then

in effect, any person who, in the course of trade or business, sells,

barters or exchanges goods, renders services, or engages in similar

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

transactions and any person who imports goods is liable for output VAT

at rates of either 10% or 0% (zero-rated) depending on the

classification of the transaction under Sec. 100 of the NIRC. Persons

registered under the VAT system7 are allowed to recognize input VAT,

or the VAT due from or paid by it in the course of its trade or business

on importation of goods or local purchases of goods or service,

including lease or use of properties, from a VAT-registered person.8

In January of 1988, respondent applied for and was granted by the BIR

zero-rated status on its sale of gold to Central Bank.9 On 28 August

1988, Deputy Commissioner of Internal Revenue Eufracio D. Santos

issued VAT Ruling No. 3788-88, which declared that [t]he sale of gold

to Central Bank is considered as export sale subject to zero-rate

pursuant to Section 100[10] of the Tax Code, as amended by Executive

Order No. 273. The BIR came out with at least six (6) other

issuances11 reiterating the zero-rating of sale of gold to the Central

Bank, the latest of which is VAT Ruling No. 036-90 dated 14 February

1990.12

Relying on its zero-rated status and the above issuances, respondent

sold gold to the Central Bank during the period of 1 August 1989 to 31

July 1991 and entered into transactions that resulted in input VAT

incurred in relation to the subject sales of gold. It then filed applications

for tax refunds/credits corresponding to input VAT for the amounts13 of

P46,177,861.12,14 P19,218,738.44,15 and P84,909,247.96.16

Respondents applications were either unacted upon or expressly

disallowed by petitioner.17 In addition, petitioner issued a deficiency

assessment against respondent when, after applying respondents

creditable input VAT costs against the retroactive 10% VAT levy, there

resulted a balance of excess output VAT.18

The express disallowance of respondents application for

refunds/credits and the issuance of deficiency assessments against it

were based on a BIR ruling BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92 dated 23

January 1992 that was issued subsequent to the consummation of the

subject sales of gold to the Central Bank which provides that sales of

gold to the Central Bank shall not be considered as export sales and

thus, shall be subject to 10% VAT. In addition, BIR VAT Ruling No. 00892 withdrew, modified, and superseded all inconsistent BIR issuances.

The relevant portions of the ruling provides, thus:

1. In general, for purposes of the term export sales only direct export

sales and foreign currency denominated sales, shall be qualified for

zero-rating.

....

4. Local sales of goods, which by fiction of law are considered export

sales (e.g., the Export Duty Law considers sales of gold to the Central

Bank of the Philippines, as export sale). This transaction shall not be

considered as export sale for VAT purposes.

....

[A]ll Orders and Memoranda issued by this Office inconsistent herewith

are considered withdrawn, modified or superseded. (Emphasis

supplied)

The BIR also issued VAT Ruling No. 059-92 dated 28 April 1992 and

Revenue Memorandum Order No. 22-92 which decreed that the

revocation of VAT Ruling No. 3788-88 by VAT Ruling No. 008-92 would

not unduly prejudice mining companies and, thus, could be applied

retroactively.19

Respondent filed three separate petitions for review with the Court of

Tax Appeals (CTA), docketed as CTA Case No. 4945, CTA Case No.

4627, and the consolidated cases of CTA Case Nos. 4686 and 4829.

In the three cases, respondent argued that a retroactive application of

BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92 would violate Sec. 246 of the NIRC, which

mandates the non-retroactivity of rulings or circulars issued by the

Commissioner of Internal Revenue that would operate to prejudice the

taxpayer. Respondent then discussed in detail the manner and extent

Page 7

TAX 2

by which it was prejudiced by this retroactive application.20 Petitioner

on the other hand, maintained that BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92 is, firstly,

not void and entitled to great respect, having been issued by the body

charged with the duty of administering the VAT law, and secondly, it

may validly be given retroactive effect since it was not prejudicial to

respondent.

In three separate decisions,21 the CTA dismissed respondents

respective petitions. It held, with Presiding Judge Ernesto D. Acosta

dissenting, that no prejudice had befallen respondent by virtue of the

retroactive application of BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92, and that,

consequently, the application did not violate Sec. 246 of the NIRC.22

The CTA decisions were appealed by respondent to the Court of

Appeals. The cases were docketed therein as CA-G.R. SP Nos. 37205,

38958, and 39435, and thereafter consolidated. The Court of Appeals,

after evaluating the arguments of the parties, rendered the questioned

Decision reversing the Court of Tax Appeals insofar as the latter had

ruled that BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92 did not prejudice the respondent

and that the same could be given retroactive effect.

In its Decision, the appellate court held that respondent suffered

financial damage equivalent to the sum of the disapproved claims. It

stated that had respondent known that such sales were subject to 10%

VAT, which rate was not the prevailing rate at the time of the

transactions, respondent would have passed on the cost of the input

taxes to the Central Bank. It also ruled that the remedies which the CTA

supposed would eliminate any resultant prejudice to respondent were

not sufficient palliatives as the monetary values provided in the

supposed remedies do not approximate the monetary values of the tax

credits that respondent lost after the implementation of the VAT ruling in

question. It cited Manila Mining Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal

Revenue,23 in which the Court of Appeals held24 that BIR VAT Ruling

No. 008-92 cannot be given retroactive effect. Lastly, the Court of

Appeals observed that R.A. 7716, the The New Expanded VAT Law,

reveals the intent of the lawmakers with regard to the treatment of sale

of gold to the Central Bank since the amended version therein of Sec.

100 of the NIRC expressly provides that the sale of gold to the Bangko

Sentral ng Pilipinas is an export sale subject to 0% VAT rate. The

appellate court thus allowed respondents claims, decreeing in its

dispositive portion, viz.:

WHEREFORE, the appealed decision is hereby REVERSED. The

respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue is ordered to award the

following tax credits to petitioner.

1) In CA-G.R. SP No. 37209P49,611,914.00

2) In CA-G.R. SP No. 38958P19,218,738.44

3) In CA-G.R. SP No. 39435P84,909,247.9625

Dissatisfied with the above ruling, petitioner filed the instant Petition for

Review questioning the determination of the Court of Appeals that the

retroactive application of the subject issuance was prejudicial to

respondent and could not be applied retroactively.

Apart from the central issue on the validity of the retroactive application

of VAT Ruling No. 008-92, the question of the validity of the issuance

itself has been touched upon in the pleadings, including a reference

made by respondent to a Court of Appeals Decision holding that the

VAT Ruling had no legal basis.26 For its part, as the party that raised

this issue, petitioner spiritedly defends the validity of the issuance.27

Effectively, however, the question is a non-issue and delving into it

would be a needless exercise for, as respondent emphatically pointed

out in its Comment, unlike petitioners formulation of the issues, the

only real issue in this case is whether VAT Ruling No. 008-92 which

revoked previous rulings of the petitioner which respondent heavily

relied upon . . . may be legally applied retroactively to respondent.28

This Court need not invalidate the BIR issuances, which have the force

and effect of law, unless the issue of validity is so crucially at the heart

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

of the controversy that the Court cannot resolve the case without

having to strike down the issuances. Clearly, whether the subject VAT

ruling may validly be given retrospective effect is the lis mota in the

case. Put in another but specific fashion, the sole issue to be

addressed is whether respondents sale of gold to the Central Bank

during the period when such was classified by BIR issuances as zerorated could be taxed validly at a 10% rate after the consummation of

the transactions involved.

In a long line of cases,29 this Court has affirmed that the rulings,

circular, rules and regulations promulgated by the Commissioner of

Internal Revenue would have no retroactive application if to so apply

them would be prejudicial to the taxpayers. In fact, both petitioner30

and respondent31 agree that the retroactive application of VAT Ruling

No. 008-92 is valid only if such application would not be prejudicial to

the respondentpursuant to the explicit mandate under Sec. 246 of the

NIRC, thus:

Sec. 246. Non-retroactivity of rulings.Any revocation, modification or

reversal of any of the rules and regulations promulgated in accordance

with the preceding Section or any of the rulings or circulars

promulgated by the Commissioner shall not be given retroactive

application if the revocation, modification or reversal will be prejudicial

to the taxpayers except in the following cases: (a) where the taxpayer

deliberately misstates or omits material facts from his return on any

document required of him by the Bureau of Internal Revenue; (b) where

the facts subsequently gathered by the Bureau of Internal Revenue are

materially different form the facts on which the ruling is based; or (c)

where the taxpayer acted in bad faith. (Emphasis supplied)

In that regard, petitioner submits that respondent would not be

prejudiced by a retroactive application; respondent maintains the

contrary. Consequently, the determination of the issue of retroactivity

hinges on whether respondent would suffer prejudice from the

retroactive application of VAT Ruling No. 008-92.

We agree with the Court of Appeals and the respondent.

To begin with, the determination of whether respondent had suffered

prejudice is a factual issue. It is an established rule that in the exercise

of its power of review, the Supreme Court is not a trier of facts.

Moreover, in the exercise of the Supreme Courts power of review, the

findings of facts of the Court of Appeals are conclusive and binding on

the Supreme Court.32 An exception to this rule is when the findings of

fact a quo are conflicting,33 as is in this case.

VAT is a percentage tax imposed at every stage of the distribution

process on the sale, barter, exchange or lease of goods or properties

and rendition of services in the course of trade or business, or the

importation of goods.34 It is an indirect tax, which may be shifted to the

buyer, transferee, or lessee of the goods, properties, or services.35

However, the party directly liable for the payment of the tax is the

seller.36

In transactions taxed at a 10% rate, when at the end of any given

taxable quarter the output VAT exceeds the input VAT, the excess shall

be paid to the government; when the input VAT exceeds the output

VAT, the excess would be carried over to VAT liabilities for the

succeeding quarter or quarters.37 On the other hand, transactions

which are taxed at zero-rate do not result in any output tax. Input VAT

attributable to zero-rated sales could be refunded or credited against

other internal revenue taxes at the option of the taxpayer.38

To illustrate, in a zero-rated transaction, when a VAT-registered person

(taxpayer) purchases materials from his supplier at P80.00, P7.3039

of which was passed on to him by his supplier as the latters 10%

output VAT, the taxpayer is allowed to recover P7.30 from the BIR, in

addition to other input VAT he had incurred in relation to the zero-rated

transaction, through tax credits or refunds. When the taxpayer sells his

finished product in a zero-rated transaction, say, for P110.00, he is not

Page 8

TAX 2

required to pay any output VAT thereon. In the case of a transaction

subject to 10% VAT, the taxpayer is allowed to recover both the input

VAT of P7.30 which he paid to his supplier and his output VAT of P2.70

(10% the P30.00 value he has added to the P80.00 material) by

passing on both costs to the buyer. Thus, the buyer pays the total 10%

VAT cost, in this case P10.00 on the product.

In both situations, the taxpayer has the option not to carry any VAT cost

because in the zero-rated transaction, the taxpayer is allowed to

recover input tax from the BIR without need to pay output tax, while in

10% rated VAT, the taxpayer is allowed to pass on both input and

output VAT to the buyer. Thus, there is an elemental similarity between

the two types of VAT ratings in that the taxpayer has the option not to

take on any VAT payment for his transactions by simply exercising his

right to pass on the VAT costs in the manner discussed above.

Proceeding from the foregoing, there appears to be no upfront

economic difference in changing the sale of gold to the Central Bank

from a 0% to 10% VAT rate provided that respondent would be allowed

the choice to pass on its VAT costs to the Central Bank. In the instant

case, the retroactive application of VAT Ruling No. 008-92 unilaterally

forfeited or withdrew this option of respondent. The adverse effect is

that respondent became the unexpected and unwilling debtor to the

BIR of the amount equivalent to the total VAT cost of its product, a

liability it previously could have recovered from the BIR in a zero-rated

scenario or at least passed on to the Central Bank had it known it

would have been taxed at a 10% rate. Thus, it is clear that respondent

suffered economic prejudice when its consummated sales of gold to the

Central Bank were taken out of the zero-rated category. The change in

the VAT rating of respondents transactions with the Central Bank

resulted in the twin loss of its exemption from payment of output VAT

and its opportunity to recover input VAT, and at the same time

subjected it to the 10% VAT sans the option to pass on this cost to the

Central Bank, with the total prejudice in money terms being equivalent

to the 10% VAT levied on its sales of gold to the Central Bank.

Petitioner had made its position hopelessly untenable by arguing that

the deficiency 10% that may be assessable will only be equal to 1/11th

of the amount billed to the [Central Bank] rather than 10% thereof. In

short, [respondent] may only be charged based on the tax amount

actually and technically passed on to the [Central Bank] as part of the

invoiced price.40 To the Court, the aforequoted statement is a clear

recognition that respondent would suffer prejudice in the amount

actually and technically passed on to the [Central Bank] as part of the

invoiced price. In determining the prejudice suffered by respondent, it

matters little how the amount charged against respondent is

computed,41 the point is that the amount (equal to 1/11th of the amount

billed to the Central Bank) was charged against respondent, resulting in

damage to the latter.

Petitioner posits that the retroactive application of BIR VAT Ruling No.

008-92 is stripped of any prejudicial effect when viewed in relation to

several available options to recoup whatever liabilities respondent may

have incurred, i.e., respondents input VAT may still be used (1) to

offset its output VAT on the sales of gold to the Central Bank or on its

output VAT on other sales subject to 10% VAT, and (2) as deductions

on its income tax under Sec. 29 of the Tax Code.42

On petitioners first suggested recoupment modality, respondent

counters that its other sales subject to 10% VAT are so minimal that this

mode is of little value. Indeed, what use would a credit be where there

is nothing to set it off against? Moreover, respondent points out that

after having been imposed with 10% VAT sans the opportunity to pass

on the same to the Central Bank, it was issued a deficiency tax

assessment because its input VAT tax credits were not enough to offset

the retroactive 10% output VAT. The prejudice then experienced by

respondent lies in the fact that the tax refunds/credits that it expected to

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

receive had effectively disappeared by virtue of its newfound output

VAT liability against which petitioner had offset the expected

refund/credit. Additionally, the prejudice to respondent would not simply

disappear, as petitioner claims, when a liability (which liability was not

there to begin with) is imposed concurrently with an opportunity to

reduce, not totally eradicate, the newfound liability. In sum, contrary to

petitioners suggestion, respondents net income still decreased

corresponding to the amount it expected as its refunds/credits and the

deficiency assessments against it, which when summed up would be

the total cost of the 10% retroactive VAT levied on respondent.

Respondent claims to have incurred further prejudice. In computing its

income taxes for the relevant years, the input VAT cost that respondent

had paid to its suppliers was not treated by respondent as part of its

cost of goods sold, which is deductible from gross income for income

tax purposes, but as an asset which could be refunded or applied as

payment for other internal revenue taxes. In fact, Revenue Regulation

No. 5-87 (VAT Implementing Guidelines), requires input VAT to be

recorded not as part of the cost of materials or inventory purchased but

as a separate entry called input taxes, which may then be applied

against output VAT, other internal revenue taxes, or refunded as the

case may be.43 In being denied the opportunity to deduct the input VAT

from its gross income, respondents net income was overstated by the

amount of its input VAT. This overstatement was assessed tax at the

32% corporate income tax rate, resulting in respondents overpayment

of income taxes in the corresponding amount. Thus, respondent not

only lost its right to refund/credit its input VAT and became liable for

deficiency VAT, it also overpaid its income tax in the amount of 32% of

its input VAT.

This leads us to the second recourse that petitioner has suggested to

offset any resulting prejudice to respondent as a consequence of giving

retroactive effect to BIR VAT Ruling No. 008-92. Petitioner submits that

granting that respondent has no other sale subject to 10% VAT against

which its input taxes may be used in payment, then respondent is

constituted as the final entity against which the costs of the tax passeson shall legally stop; hence, the input taxes may be converted as costs

available as deduction for income tax purposes.44

Even assuming that the right to recover respondents excess payment

of income tax has not yet prescribed, this relief would only address

respondents overpayment of income tax but not the other burdens

discussed above. Verily, this remedy is not a feasible option for

respondent because the very reason why it was issued a deficiency tax

assessment is that its input VAT was not enough to offset its retroactive

output VAT. Indeed, the burden of having to go through an unnecessary

and cumbersome refund process is prejudice enough. Moreover, there

is in fact nothing left to claim as a deduction from income taxes.

From the foregoing it is clear that petitioners suggested options by

which prejudice would be eliminated from a retroactive application of

VAT Ruling No. 008-92 are either simply inadequate or grossly

unrealistic.

At the time when the subject transactions were consummated, the

prevailing BIR regulations relied upon by respondent ordained that gold

sales to the Central Bank were zero-rated. The BIR interpreted Sec.

100 of the NIRC in relation to Sec. 2 of E.O. No. 581 s. 1980 which

prescribed that gold sold to the Central Bank shall be considered export

and therefore shall be subject to the export and premium duties. In

coming out with this interpretation, the BIR also considered Sec. 169 of

Central Bank Circular No. 960 which states that all sales of gold to the

Central Bank are considered constructive exports.45 Respondent

should not be faulted for relying on the

BIRs interpretation of the said laws and regulations.46 While it is true,

as petitioner alleges, that government is not estopped from collecting

taxes which remain unpaid on account of the errors or mistakes of its

Page 9

TAX 2

agents and/or officials and there could be no vested right arising from

an erroneous interpretation of law, these principles must give way to

exceptions based on and in keeping with the interest of justice and

fairplay, as has been done in the instant matter. For, it is primordial that

every person must, in the exercise of his rights and in the performance

of his duties, act with justice, give everyone his due, and observe

honesty and good faith.47

The case of ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation v. Court of Tax

Appeals48 involved a similar factual milieu. There the Commissioner of

Internal Revenue issued Memorandum Circular No. 4-71 revoking an

earlier circular for being erroneous for lack of legal basis. When the

prior circular was still in effect, petitioner therein relied on it and

consummated its transactions on the basis thereof. We held, thus:

. . . .Petitioner was no longer in a position to withhold taxes due from

foreign corporations because it had already remitted all film rentals and

no longer had any control over them when the new Circular was issued.

...

....

This Court is not unaware of the well-entrenched principle that the

[g]overnment is never estopped from collecting taxes because of

mistakes or errors on the part of its agents. But, like other principles of

law, this also admits of exceptions in the interest of justice and fairplay .

. . . In fact, in the United States, . . . it has been held that the

Commissioner [of Internal Revenue] is precluded from adopting a

position inconsistent with one previously taken where injustice would

result therefrom or where there has been a misrepresentation to the

taxpayer.49

Respondent, in this case, has similarly been put on the receiving end of

a grossly unfair deal. Before respondent was entitled to tax refunds or

credits based on petitioners own issuances. Then suddenly, it found

itself instead being made to pay deficiency taxes with petitioners

retroactive change in the VAT categorization of respondents

transactions with the Central Bank. This is the sort of unjust treatment

of a taxpayer which the law in Sec. 246 of the NIRC abhors and forbids.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED for lack of merit. The Decision of

the Court of Appeals is AFFIRMED. No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED. [Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Benguet

Corporation, 463 SCRA 28(2005)]

G.R. No. 168056. September 1, 2005.*

ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST (Formerly AASJAS) OFFICERS

SAMSON S. ALCANTARA and ED VINCENT S. ALBANO,

petitioners, vs. THE HONORABLE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY

EDUARDO ERMITA; HONORABLE SECRETARY OF THE

DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE CESAR PURISIMA; and HONORABLE

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE GUILLERMO PARAYNO,

JR., respondents.

G.R. No. 168207. September 1, 2005.*

AQUILINO Q. PIMENTEL, JR., LUISA P. EJERCITO-ESTRADA,

JINGGOY E. ESTRADA, PANFILO M. LACSON, ALFREDO S. LIM,

JAMBY A.S. MADRIGAL, AND SERGIO R. OSMEA III, petitioners,

vs. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO R. ERMITA, CESAR V.

PURISIMA, SECRETARY OF FINANCE, GUILLERMO L. PARAYNO,

JR., COMMISSIONER OF THE BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE,

respondents.

G.R. No. 168461. September 1, 2005.*

ASSOCIATION OF PILIPINAS SHELL DEALERS, INC. represented

by its President, ROSARIO ANTONIO; PETRON DEALERS

ASSOCIATION represented by its President, RUTH E. BARBIBI;

ASSOCIATION OF CALTEX DEALERS OF THE PHILIPPINES

represented by its President, MERCEDITAS A. GARCIA; ROSARIO

ANTONIO doing business under the name and style of ANB

Intelligentia et Scientia Semper Mea

PINEDAPCGRNMAN

NORTH SHELL SERVICE STATION; LOURDES MARTINEZ doing

business under the name and style of SHELL GATEN.

DOMINGO; BETH-ZAIDA TAN doing business under the name

and style of ADVANCE SHELL STATION; REYNALDO P.

MONTOYA doing business under the name and style of NEW

LAMUAN SHELL SERVICE STATION; EFREN SOTTO doing

business under the name and style of RED FIELD SHELL

SERVICE STATION; DONICA CORPORATION represented by its

President, DESI TOMACRUZ; RUTH E. MARBIBI doing business

under the name and style of R&R PETRON STATION; PETER M.

UNGSON doing business under the name and style of CLASSIC

STAR GASOLINE SERVICE STATION; MARIAN SHEILA A. LEE

doing business under the name and style of NTE GASOLINE &

SERVICE STATION; JULIAN CESAR P. POSADAS doing business

under the name and style of STARCARGA ENTERPRISES;

ADORACION MAEBO doing business under the name and style

of CMA MOTORISTS CENTER; SUSAN M. ENTRATA doing

business under the name and style of LEONAS GASOLINE

STATION and SERVICE CENTER; CARMELITA BALDONADO

doing business under the name and style of FIRST CHOICE

SERVICE CENTER; MERCEDITAS A. GARCIA doing business

under the name and style of LORPED SERVICE CENTER;

RHEAMAR A. RAMOS doing business under the name and style of

RJRAM PTT GAS STATION; MA. ISABEL VIOLAGO doing

business under the name and style of VIOLAGO-PTT SERVICE

CENTER; MOTORISTS HEART CORPORATION represented by its

Vice-President for Operations, JOSELITO F. FLORDELIZA;

MOTORISTS HARVARD CORPORATION represented by its VicePresident for Operations, JOSELITO F. FLORDELIZA; MOTORISTS

HERITAGE CORPORATION represented by its Vice-President for

Operations, JOSELITO F. FLORDELIZA; PHILIPPINE STANDARD

OIL CORPORATION represented by its Vice-President for

Operations, JOSELITO F. FLORDELIZA; ROMEO MANUEL doing

business under the name and style of ROMMAN GASOLINE

STATION; ANTHONY ALBERT CRUZ III doing business under the

name and style of TRUE SERVICE STATION, petitioners, vs.

CESAR V. PURISIMA, in his capacity as Secretary of the

Department of Finance and GUILLERMO L. PARAYNO, JR., in his

capacity as Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondents.

G.R. No. 168463. September 1, 2005.*

FRANCIS JOSEPH G. ESCUDERO, VINCENT CRISOLOGO,

EMMANUEL JOEL J. VILLANUEVA, RODOLFO G. PLAZA,

DARLENE ANTONINO-CUSTODIO, OSCAR G. MALAPITAN,

BENJAMIN C. AGARAO, JR. JUAN EDGARDO M. ANGARA,

JUSTIN MARC SB. CHIPECO, FLORENCIO G. NOEL, MUJIV S.

HATAMAN, RENATO B. MAGTUBO, JOSEPH A. SANTIAGO,

TEOFISTO DL. GUINGONA III, RUY ELIAS C. LOPEZ, RODOLFO Q.

AGBAYANI and TEODORO A. CASIO, petitioners, vs. CESAR V.

PURISIMA, in his capacity as Secretary of Finance, GUILLERMO L.

PARAYNO, JR., in his capacity as Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, and EDUARDO R. ERMITA, in his capacity as Executive

Secretary, respondents.

G.R. No. 168730. September 1, 2005. *

BATAAN GOVERNOR ENRIQUE T. GARCIA, JR., petitioner, vs.

HON. EDUARDO R. ERMITA, in his capacity as the Executive

Secretary; HON. MARGARITO TEVES, in his capacity as Secretary

of Finance; HON. JOSE MARIO BUNAG, in his capacity as the OIC

Commissioner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue; and HON.

ALEXANDER AREVALO, in his capacity as the OIC Commissioner

of the Bureau of Customs, respondents.

Page 10

TAX 2