Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Microsoft Word Document

Uploaded by

Adeeba IfrahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Microsoft Word Document

Uploaded by

Adeeba IfrahCopyright:

Available Formats

Interval and Ratio Scales.

A more precise measure still is one that specifies the

exact distances (or intervals) between one measurement and another. Any sys.

tem that relies on an established and consistent unit of measurementwhether

it is dollars, feet, or degrees of temperaturesatisfies the criterion of an interval

scale. However, the validity of measuring attitudes and feelings on an interval

scale is a topic of much discussion and some disagreement. In the case of Kim's

question-naire, we might ask if it is legitimate to assume that respondents using

the 5-point scalefrom very important (5) to not at all (t )are employing a

consistent incre ment of difference between responses of 4 versus 5 or 3 versus

4. If we assume that they are not employing a consistent interval of difference,

then the attitudinal scale is, in fact, functioning as an ordinal measurement. A

further level of measurement precision is achieved with a ratio scale, whereby an

absolute zero point on the scale can be established. This means that something

that measures 20 on a ratio scale is legitimately understood as constituting twice

the quantity of 10. In practical terms, there are few interval scales that are not

also ratio scales, but one exception is that of temperature. Indeed, we cannot

claim that 72 degrees is twice as hot as 36 degrees. However, we can assume

consistent mea-suring intervals; the difference between and 10 degrees is the

same as the differ ence between 20 and 25 degrees.' These distinctions among

types of measurement precision frequently come into play in correlational

research because so many variablesfrom demographic characteristics, to

attitudes and behaviors, to physical propertiesmust be mea-sured. And

because different variables lend themselves to varying levels of measure-ment

precision, great attention is paid to establishing legitimate data collection

instruments and appropriate modes of quantitative analysis.

example, Kim presents the calculated correlations among all four of the

measures of community, both for Kentlands and for Orchard Village (a

pseudonym for the typ-ical suburban development) (see Figure 8.9). As it turns

out, all four measures of community are highly and positively correlated with

each other, for each neighbor-hood development. So, for example, the Kentlands'

ratings of the effect of various physical features on their sense of attachment

have a similar pattern to their ratings for social interaction, and so on. In other

words, in the perception of the residents, the role of the various physical features

in achieving a sense of attachment, pedestri-anism, social interaction, and sense

of identity are quite similar. However, if the pattern of ratings on any two

measures had been quite different, it would have been described as a negative

correlation. All calculated correlation coefficients are indicated within a range of

-1.00 (a negative correlation) to +1.00 (a positive correlation); and a correlation

coefficient close to 0 indicates virtually no consistent relationship between

variables.

You might also like

- IIT Guwahati MDes Project Report Assessment 2018-2019Document2 pagesIIT Guwahati MDes Project Report Assessment 2018-2019Adeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Ngvghcvycfyctrcxrtnhchgchnfchchchhgkvyig Gyui VHGCNHCFDXSFCVGMJ.LDocument1 pageNgvghcvycfyctrcxrtnhchgchnfchchchhgkvyig Gyui VHGCNHCFDXSFCVGMJ.LAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- zxVCSYasyuxcf Uasic VuiDocument1 pagezxVCSYasyuxcf Uasic VuiAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- MBBL - Model Building Bylaws 2016Document268 pagesMBBL - Model Building Bylaws 2016RAJEEV JHANo ratings yet

- Case Studies of Selected Streets in ChennaiDocument74 pagesCase Studies of Selected Streets in ChennaiAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Nhchgchnfchchchhgkvyig Gyui VHGCNHCFDXSFCVGMJ.LDocument1 pageNhchgchnfchchchhgkvyig Gyui VHGCNHCFDXSFCVGMJ.LAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- 20101224comics Worls and The World of Comics PDFDocument320 pages20101224comics Worls and The World of Comics PDFAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Abstract Reasoning - Test 1Document9 pagesAbstract Reasoning - Test 1playnlearnwivmeNo ratings yet

- BDes Revised Course Structure For First YearDocument6 pagesBDes Revised Course Structure For First YearAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Animation StudyDocument5 pagesAnimation StudyAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- 04.bus Station DesignDocument41 pages04.bus Station DesignVenkat Chowdary100% (1)

- 8118 1Document24 pages8118 1Adeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Experts Lecture On Tentative Date: ND RDDocument1 pageExperts Lecture On Tentative Date: ND RDAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Agencies Involved in Low CostDocument44 pagesAgencies Involved in Low CostAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- ITC Rajputana FactSheetDocument5 pagesITC Rajputana FactSheetAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Formation of HimalayasDocument8 pagesFormation of HimalayasAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- European Hill Architecture: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument23 pagesEuropean Hill Architecture: Submitted To: Submitted byAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Dhajji Manual Final 2010Document40 pagesDhajji Manual Final 2010filip_vidovic665No ratings yet

- Ar-321 Architectural Design - VL: RD THDocument7 pagesAr-321 Architectural Design - VL: RD THAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Paradigms For DesignDocument18 pagesParadigms For DesignAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Building Conservation and SustainabiltyDocument10 pagesBuilding Conservation and SustainabiltyAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Draft DPRDocument54 pagesDraft DPRSaket MehtaNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh: Urban Planning ConceptsDocument10 pagesChandigarh: Urban Planning ConceptsAbhishek ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- IndoreTLBN (English)Document89 pagesIndoreTLBN (English)Adeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh: Urban Planning ConceptsDocument10 pagesChandigarh: Urban Planning ConceptsAbhishek ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Fire ProtectionDocument37 pagesFire ProtectionAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- Amer Fort Palace ArchitectureDocument5 pagesAmer Fort Palace ArchitectureAdeeba IfrahNo ratings yet

- 03 Salt Lake City WebDocument165 pages03 Salt Lake City Webrichuricha100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 5.5 Inch 24.70 VX54 6625 4000 2 (Landing String)Document2 pages5.5 Inch 24.70 VX54 6625 4000 2 (Landing String)humberto Nascimento100% (1)

- Anita Desai PDFDocument9 pagesAnita Desai PDFRoshan EnnackappallilNo ratings yet

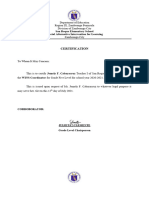

- Certification 5Document10 pagesCertification 5juliet.clementeNo ratings yet

- 677 1415 1 SMDocument5 pages677 1415 1 SMAditya RizkyNo ratings yet

- QDEGNSWDocument2 pagesQDEGNSWSnehin PoddarNo ratings yet

- Geographic Location SystemsDocument16 pagesGeographic Location SystemsSyed Jabed Miadad AliNo ratings yet

- AC413 Operations Auditing Outline & ContentDocument29 pagesAC413 Operations Auditing Outline & ContentErlie CabralNo ratings yet

- Department of Information TechnologyDocument1 pageDepartment of Information TechnologyMuhammad ZeerakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4-Historical RecountDocument14 pagesChapter 4-Historical RecountRul UlieNo ratings yet

- Arrest of Leila de Lima (Tweets)Document74 pagesArrest of Leila de Lima (Tweets)Edwin MartinezNo ratings yet

- BA 424 Chapter 1 NotesDocument6 pagesBA 424 Chapter 1 Notesel jiNo ratings yet

- Tait V MSAD 61 ComplaintDocument36 pagesTait V MSAD 61 ComplaintNEWS CENTER MaineNo ratings yet

- AEF3 File4 TestADocument5 pagesAEF3 File4 TestAdaniel-XIINo ratings yet

- Einstein AnalysisDocument2 pagesEinstein AnalysisJason LiebsonNo ratings yet

- SM pc300350 lc6 PDFDocument788 pagesSM pc300350 lc6 PDFGanda Praja100% (2)

- Zapffe, Peter Wessel - The Last Messiah PDFDocument13 pagesZapffe, Peter Wessel - The Last Messiah PDFMatias MoulinNo ratings yet

- Pro ManualDocument67 pagesPro ManualAlan De La FuenteNo ratings yet

- Scan To Folder Easy Setup GuideDocument20 pagesScan To Folder Easy Setup GuideJuliana PachecoNo ratings yet

- Organizational Development ProcessDocument1 pageOrganizational Development ProcessMohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Bible Study With The LDS MissionaryDocument53 pagesBible Study With The LDS MissionaryBobby E. LongNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Strategy: Atar Thaung HtetDocument16 pagesHuman Resource Strategy: Atar Thaung HtetaungnainglattNo ratings yet

- DSP Question Paper April 2012Document2 pagesDSP Question Paper April 2012Famida Begam100% (1)

- Writing Essays B1Document6 pagesWriting Essays B1Manuel Jose Arias TabaresNo ratings yet

- Quieting of TitleDocument11 pagesQuieting of TitleJONA PHOEBE MANGALINDANNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth scholarships to strengthen global health systemsDocument4 pagesCommonwealth scholarships to strengthen global health systemsanonymous machineNo ratings yet

- Timeline of The Human SocietyDocument3 pagesTimeline of The Human SocietyAtencio Barandino JhonilNo ratings yet

- SF3 - 2022 - Grade 8 SAMPLEDocument2 pagesSF3 - 2022 - Grade 8 SAMPLEANEROSE DASIONNo ratings yet

- Cityam 2011-09-19Document36 pagesCityam 2011-09-19City A.M.No ratings yet

- Philippine Idea FileDocument64 pagesPhilippine Idea FileJerica TamayoNo ratings yet

- India's Contribution To World PeaceDocument2 pagesIndia's Contribution To World PeaceAnu ChoudharyNo ratings yet