Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2003 Casella, The False Allure of Security Technologies

Uploaded by

Achal ThakoreCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2003 Casella, The False Allure of Security Technologies

Uploaded by

Achal ThakoreCopyright:

Available Formats

The False Allure of Security Technologies

Author(s): Ronnie Casella

Source: Social Justice, Vol. 30, No. 3 (93), The Intersection of Ideologies of Violence (2003), pp. 82

-93

Published by: Social Justice/Global Options

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29768210

Accessed: 13-07-2015 21:02 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Social Justice/Global Options is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Justice.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of

Security Technologies

Ronnie

THE

Casella

BEGAN

TRADEMAGAZINE,

SECURITYINDUSTRY

AMERICAN

SCHOOLANDUNIVERSITY,

an article about school safetywith the following real-life scenario (Kennedy,

2001):

students were enjoying recess on the playground in the Piano

Independent School District, Texas, a suspicious man sitting in a parked

Cadillac tried to lure some of the children over to the car.

As

the teacher on duty saw what was happening and began to

approach the car, theman drove off.That might have been the end of the

incident, except thatthe teacherwas carrying a two-way radio. She called

back to the school office, and someone immediately called 911. A few

minutes later, theman was in custody.

When

"He was caught before he got out of theneighborhood," saysKen Bangs,

director of police, security,and student safetyfor thePiano district. "Did

we dodge a bullet? I believe thatwe did."

For Bangs, itwas more proof that the district's increasing use of radios

was paying dividends in safer campuses, and more secure students and

staff."Having these radios makes a ton of difference," says Bangs.

Like many articles that appear inAmerican School and University, Security

Technology and Design, SecurityManagement, and other trademagazines of the

security industry, theuse of technology is described as a boon for school safety,

and thenewest advances and improvements in technology are regularly featured

in articles and represented in advertisements that appear in themagazines. In

addition to radios, these technologies include metal detectors, scanners, close

circuit televisions (CCTVs), iris recognition systems, and other forms of surveil

is assistant professor of educational foundations and

Casella

(e-mail: casellar@ccsu.edu)

secondary education atCentral Connecticut State University (New Britain, CT 06050). He is the author

of "Being Down": Challenging Violence inUrban Schools (New York: Teachers College Press, 2001)

and At Zero Tolerance: Punishment, Prevention, and School Violence

(New York: Peter Lang

Ronnie

Publishing, 2001).

82 Social Justice Vol. 30, No. 3 (2003)

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of Security Technologies

83

lance, detection, access control, and biometric equipment. Many of these items

depend on technologies (such as digitalized networks and lasers) that were

developed by military and security industry scientists beginning in the 1940s

primarily forpolice and national security purposes during theCold War. Today,

theprevalence in high schools ofwhat De vine (1996) called "techno-security" is

an example of how these developments in technology have altered our public

spaces, institutions,and homes. In the case of schools, the use of techno-security

epitomizes fear of violence as well as fear of legal liability thatconvinces school

district administrators that security technology isworth the expenditures. How?

ever, italso epitomizes the inroads thatsecuritybusinesses have made in thepublic

school market. Peter Blouvelt, the executive director of theNational Alliance for

Safe Schools, remarked about security vendors: "Schools have become a major

market for these guys. The proliferation of security equipment for schools has

taken off (cited inLight, 2002: 3).

Schools are just one example of people's increased use and acceptance of

security technologies in theUnited States. Government buildings, stores, offices,

workplaces, recreation areas, streets, and homes have also been outfittedwith

CCTVs, biometric equipment, scanners, detectors, not tomention alarms, locks,

and intercoms.At a security industryconference I attended as part of the research

for this article, a spokesperson for a security corporation told conference partici?

pants that,according to research, inNew York City an individual was likely tobe

caught on a security camera about seven times each day without knowing it; in

London, thenumberwas double that.Although theuse of security technologies is

often explained as a need during times ofwanton violence and crime, the allure of

technology and humans' fascination with gadgets and equipment partly explain

why security technology is rapidly becoming a fixture in even themost idyllic

areas. In thecase of schools, thoughproponents of technologies warn against their

misuse, theystillbelieve thatCCTVs, scanners, and other advanced technologies

are essential for any overall school safety plan (Townley and Martinez, 1995;

Kosar and Ahmed, 2000; Trump, 1999; Fickes, 2000). Moreover, corporate

incentives and federal support have made itpossible for low-budget institutions

and individuals to invest in security.

The mass installation of security technologies is one aspect of what Lyon

(1994) referred to as a "surveillance society," whereby security items are at once

ubiquitous and invisible. People accept them inpublic and private places and often

acquiesce to thegreater restrictionson theircivil rightsand privacy thatensue due

to theiruses (see also Beger, 2002; Casella, 2003). Postman (1992) stated that in

such a society, which he described as a technopoly, individuals find it almost

impossible to thinkoutside paradigms devoted to scientism, objectivity, and order.

Critics of technology do not dismiss some key aspects (e.g., extending the lifespan

of individuals and providing comfort), but theyare skeptical of thepromises made

in the name of technology and itsunrestrained use in society.

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84

Casella

Investing inTechnology

In using public schools as a case study tobetter understand theuse of security

technologies inU.S. society, one of the firstaspects one should consider is their

cost. These costs include the installation, maintenance, and upgrading of the

security technology, and thehiring of personnel to oversee it.Costs are difficult

to calculate partly because school district accountants often combine figures

pertaining to technologywith other safetyexpenditures. For example, theChicago

public school system spent about $35 million during the 2000-2001 school year

on security,but this includedmoney earmarked for technology and tech-support,

as well as police officers, security guards, and violence prevention and character

education programs.Moreover, the long-termcosts of upgrading andmaintenance

are also difficult to ascertain because these numbers are not kept as separate items.

The issue of cost ismuddled furtherbecause securityprofessionals claim that

schools and other sites actually save money by investing in technology and allege

theycan provide proof through simplemath calculations. During the 1999-2000

school year, a Connecticut high school acquired a highly sophisticated CCTV and

motion detector system,which was reported in thecity newspaper and featured in

two security trademagazines (Casella, 2001). The CCTV system included 63

cameras, 47 of which were located outside the school. Almost half of all the

cameras had pan-tilt-zoom capabilities "capable of reading a license plate number

fromacross theparking lot."The systemwas also networked to laptop computers

in two police cruisers and the police department,who could control it through

remote control. The CCTV andmotion detector system cost the school $300,000.

However, an article in a trademagazine claimed the expenditure is justified

because the school would save $200,000 a year by detecting vandalism before it

occurs (Sorrentino, 2002). Itwas not clear in the article how the author arrived at

this conclusion, and none of the claims made by security officials regarding the

possibility of saving money could be verified.

Security corporations promote theirproducts throughdonations and the free

installation of security equipment in schools and in numerous other sites, includ?

ing offices, restaurant chains, and recreation areas. Vanguard ofMassachusetts

offers free equipment and installation of technology thatwould ordinarily cost

$40,000 to $300,000, depending on features.WorldNet Technologies in Seattle

and AvalonRF in San Diego offer free installation of theirproductWeaponScan

80?, an advanced metal (and plastic) detector thatwas originally developed by

theNavy during theCold War to trackSoviet submarines (Light, 2002). The most

importantbenefit for corporations from these donations and pro bono work is the

profit theyreceive from themonthly payments forupgrading andmaintaining the

equipment. Corporations also benefit from contractual clauses thatallow them to

feature the recipient of the equipment in theirpromotional materials and ads in

trademagazines. WebEyeAlert includes in its ads news articles from theBoston

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of Security Technologies

85

Business Journal and theDerry News ofNew Hampshire on the schools thathave

received itsweb-CCTV monitoring system.This technology allows police offic?

ers to monitor students through CCTVs, modems, computers, and Internet

networks.

An analysis of the ads allows one tounderstand theirpower in enticing school

officials and others to invest in technologies. The WebEyeAlert pamphlet depicts

various securitymarkets and highlights the fact that security technologies are

being introduced into almost all public and private places, including schools,

homes, transportation stations, hospitals, cafeterias, and outdoor areas. The

company also markets tomunicipal buildings, banks, malls, prisons, stores, and

airports.At the center of thepamphlet is thepicture of a school and a school bus.

Another picture depicts a young couple proudly standing outside their home;

young, upwardly mobile, good-looking professionals, theywill probably have

children and thereforehave concerns about school safety, a connection that is

made visually by the intersectionof their image with thatof the school. A picture

of a hospital emergency entrance and ambulance also intersectswith the school

image, again drornming up concerns about safety for oneself and one's family.

Visually connecting the image of the school to that of the police officer in his

cruiser is a white bubble. The officer shown is gaining visual access through the

Internet to the "real-time video surveillance" cameras in the school. This ad

encapsulates the security industry'swidespread efforts to convince individuals

and institutionsof the alleged wisdom of investing in security devices.

The Role of the Federal Government

As noted, security corporations often donate security equipment and its

installation in schools. Where does all themoney come from tomaintain and

upgrade (and on occasions purchase) this equipment given schools' budgetary

deficits? The answer lies largely in the financial support offered by the federal

government for the research and commercialization of security technologies.

Beginning in 2003, schools were identified as potential sites for terroristattacks

and the newly created U.S. Department of Homeland Security made funds

available to schools to purchase security technology. This department appropri?

ated over $350 million for, among other things,hiring high school police officers

and buying securityequipment through itsPublic Safety and Community Policing

Grants. Other departments that offer funds for similar goals include theU.S.

Department of theTreasury (through itsSafe Schools Initiative,which also funds

research conducted by theU.S. Secret Service), theU.S. Department ofEducation

(through itsEmergency Response and Crisis Management Grant Program and its

Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act), and theU.S. Department of

Justice. Schools are not the only ones to receive generous support. In 2001, all

taxpayers began tobenefit from a new tax code related to security.The Securing

America InvestmentAct of2001 (HR 2970), which amended the InternalRevenue

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86

Casella

of 1986, allows security devices in buildings and private homes to be

considered an expense that is not chargeable to capital accounts; hence, security

technology became a taxwrite-off.

Additionally, the"No Child Left Behind" law, passed by President George W.

Bush in 2002, provided funding for the School Security Technology Center

(SSTC) at Sandia National Laboratories. Located inAlbuquerque, New Mexico,

Sandia employs more than 8,000 scientists, engineers, mathematicians, techni?

Code

cians, and support personnel; the laboratorywas established in 1941 by theU.S.

Department of Energy to support itsnuclear weapons program. SSTC distributes

informationabout school security and trains school employees to choose and use

theright technology for theirschools. In 1999,Mary Green, an SSTC employee,

published The Appropriate and Effective Use of Security Technologies in U.S.

Schools through theU.S. Department of Justice. It is considered one of themost

comprehensive publications on the subject. SSTC is also involved in several

security initiatives, including work with Albuquerque public schools to imple?

ment a system that uses hand geometry to identify parents and guardians of

children (see Figure 1).When parents or guardians register theirchildren, theyare

assigned a personal identificationnumber (PIN) and are asked toplace theirhand

on a pad thatuses biometric technology to record theirhand features. Each time

someone picks up a child at school, he or she enters thePIN and places a hand on

thepad. If thePIN and thehand geometrymatch the information in the system, the

person is allowed to take the child (Kennedy, 2001).

can*cmed

Exhibit

Miat

4.4.ItltMUaUd

are

Mvend

of

Momvcric

her*

fatontlOm

lypa*

for

a hi&coaOdencc

control

urllb

of?ccorscy.

entry

Figure 1: From Mary Green (1999: 111; Exhibit 4.4 visual). Demonstrating the uses of iris scanning,

a palm reader, and a fingerprint reader. Individuals enter a PIN and gain access to the school if the

biometric reading matches stored information in a security database.

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of Security Technologies

Overseeing

87

Youth and Others

The young man inFigure 2 has long hair and wears jeans and sneakers (and

boots in thebottom rightcorner image). His hair lengthand clothing contrastwith

theguard's shorthair and uniform.The guard is theoverseer and theyouth is the

suspect. The overseers, however, are also the suspects fora higher level of security

professional (Lyon, 1994). Those who use security equipment on others also have

it trained on themselves. An interesting characteristic of the ads is that the

individuals being searched or having theirbody parts scanned are depicted as

content and sometimes happy (thewoman inFigure 1 is smiling). A 2002 Garrett

Metal Detectors ad shows a young, white, handsome man smiling broadly while

a securityprofessional searches him using thetop-of-the-lineGarrett SuperScanner.

In a 2001 Garrett ad, another person in tatteredjeans and sneakers ispictured being

searched by someone holding a metal detector. A sturdyarm entering the frame

isholding theSuperWand and is examining thefringedcuffsof theperson's jeans,

shown only from theknees down. The advertisement claims thatthe "SuperWand

is very easy and fun to use."

zone

Exhibit3.10.Thiato anunmpteofprocedure*

forusing? handheldmetaldetectorthathas at leasta 10-ineh

Figure 2: From Mary Green (1999: 88; Exhibit 3.10 visual). The

guards on how to use a handheld metal detector to search students.

illustration instructs school

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88

Casella

The federal government's role in accelerating the use of security devices in

U.S. society is demonstrated by the taxwrite-off forpurchases of securitydevices,

formationof theDepartment ofHomeland Security, safe school grants, support of

the Sandia National Laboratories, publications thatpromote advanced security

technologies, and demonstrations of biometric security options for schools.

Beyond that,security corporations and the federal government present amodel of

desirable behavior through the complacent, even pleased, people depicted in the

figures. Such ads ultimately seek topersuade individuals that they should allow

themselves to be subject to routine searches, have their bodies measured and

touched by lasers and scanners, and have information about them stored in

databases ?

information that can thenbe shared with a greater range of federal

organizations and police departments thanks to theUSA Patriot Act of 2001.

Welcoming

Security Technologies

intoOne's

Life

Beyond the federal support and corporate benefits and incentives stands the

allure of technology and an almost myth-making quality to induce individuals to

embrace the surveillance society inwhich they live. Corporate advertisers play on

people's fears topromote technology as theway of thefutureand its increasing use

as inevitable: "Take a closer look at theLG IrisAccess 3000 ?

it's the look of

a

Electronics

to

2002

LG

advertisement

claimed

Inc., for

U.S.A.,

by

things come,"

an iris identification system.The president of Evolution Software, Inc., explained

at a 2001 conference that "wearable security computer systems" would have

technology "integrated in everyday life." She demonstrated a wearable computer

equipped with voice recognition technology: a monocle strapped toher head (the

computer screen), a littlepouch on her hip (the computer), and a micro-keyboard

attached toone hand; a hidden camera on her shoulder recorded her surroundings

and could be projected on themonocle computer screen. Then she explained that

the armed forces were interested in the "adoption of the technology formotion

tracking systems and 3D augmented systems." Though the equipment makes one

look part robot, the integration of technology with everyday life is a popular

security industry item, a staple of security advertisements, and is commonly

alluded toby school securitydealers when theyexplain the "integration," "natural

fit," or "harmony" between security technology and humans.

These areworrisome claims considering thattechnology has demonstrated the

success of science, but not necessarily the success of society. Although the

sophistication of technology has increased, society has not always benefited

(Collingridge, 1980;Weisberg, 2000). In thephilosophy and sociology of technol?

ogy, there ismuch agreement about what is sometimes referred to as theparadox

of technology (Durbin, 1989; Scarbrough and Corbett, 1992) or what Tenner

called the "revenge of unintended consequences"

(1996). Examples of this

on

the environment, work,

to

references

include

technology's impact

paradox

to

nature:

the

closeness

and

of

life,

way

technology makes lifemore

quality

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

89

The False Allure of Security Technologies

leisurely and busier at the same time; theway technology helps to save lives but

also causes deaths and introduces new ways of dying. Technology has enabled

individuals toproduce enough food to feed theworld, yet hunger persists; theatom

was split, yetwar became more dangerous.

Partly because of the inabilityof technology to live up to thepromises of those

?

frommanufac?

who develop and sell it, theproduction of security equipment

?

relies not only on proclamations about

turer,distributor,dealer, and end-user

protective qualities, but also on scientism, images of power and omniscience, and

claims about cost-effectiveness and simplicity of use.While describing safetyand

how itis achieved, ads also describe technology design and efficiency. "Technolo?

gies tomanage people, openings, and assets. A flexible design, seamless integra?

tion capabilities, and state-of-the-arttechnology make InterAccess an essential

solution for any organization," claimed a 2002 brochure from IR Interflex, of

Forestville, Connecticut, for access control equipment for offices, government

buildings, and schools. A CEIA USA, Ltd., 2002 single-page brochure stated:

CEIA, theworld's leadingmanufacturer ofMetal Detectors, presents the

Metal Detector is engineered and designed to

Classic. This walk through

meet the specific needs of public facilities such as: schools, hotels,

amusement parks, and city halls. The Classic provides the required

securitywith a high level of operating efficiency. The leading edge of

technology features a high flow rate of people through the gate with

minimal alarms.

Figure 3: Sony Electronics, Inc., Surveillance and E-Monitoring

2003, front cover. Sleek, functional, futuristic security gear.

Systems General Catalog

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002

90

Casella

Beyond such descriptions, security products tend visually to be silver and

black, sleek-looking, futuristic,durable, and rugged (see Figure 3 for an example

of Sony security systems). They are designed to be aesthetically appealing,

especially tomen. This style of design iswhat Pacey (1999: 82) referred to as a

"combat-ready look frommilitary equipment to symbolize no-nonsense func?

tional rigor" in his description of home electronics gear marketed tomen (with

theirblack matte finishes, digital displays, and push-button controls).

A tantalizing effect exerted by security devices is related to the presumed

acceptance by individuals of science and technology (see Figure 4). The hand in

thepalm reader seems perfectly at home, especially when juxtaposed to thehand

entering the technological age (from a muted color at thewrist and lower palm to

thebrilliant Technicolor stripes at the fingers). The dawn of classical science is

represented in the drawing of thehuman body, which is surrounded by scientific

jargon that is common enough to be understood, but esoteric enough to sound

scientific, including themention of DNA, iris, and keyboard stroke.

Figure 4: TR Interflex, subsidiary of IR Ingersoll Rand, advertisement booklet, 2002, p. 16. The hand

in the bottom leftcorner enters the technological age, as does the hand on the palm reader. Classical

science (represented by the image at top) enters the "future of biometrics,*' which includes signature,

keystroke, iris,DNA,

and retina recognition systems.

Companies use thismelding of humanity and techno-science to convince

individuals to submit to devices and to accept a world inwhich surveillance is

common. When young people are asked to stand spread-legged at a school

entrance or workers are asked to have their hand measurement taken before

entering an office, the interactionbetween the overseer and the suspect depends

on thecompliance of the suspect. Compliance is achieved through the imposition

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of Security Technologies

91

of a codified authority (the presence of rules, policies, and laws), through actual

punishment of transgressors, and by persuading individuals thatwhat is being

asked of them is a natural part of life. In past generations, imagine the shock

expressed by individuals who, for the firsttime,had to punch in atwork using a

time clock. Yet, ithas become a natural part of workplaces and the recording of

one's "time in" and "time out" isexpected. For workplace managers using security

technologies, its use is usually for financial gain and expediency, while for the

federal government, the aim is information gathering; for the individual who

submits to it, it is toprove ones innocence without having done anythingwrong.

Police forces in theU.S. aremaking greater use of security technologies. For

example, theNew York City Police Department is considering putting facial

recognition technology in the 3,000 CCTVs already mounted in public housing

units. This will allow police officials to record the facial features of public

housing occupants and to run their features through various crime analysis

databases. The cameras and facial recognition technology will thus be used on

poor andmostly nonwhite people. New Jerseypolice cruisers have been outfitted

with cameras todocument trafficstops along theNew JerseyTurnpike. Cameras

were installed in response to accusations of police brutality, but they also

document who is riding thehighways, atwhat time, and on what day. Are people

aware they are being captured on film several times each day, that information

about them is increasingly run throughdatabases and kept on record, or that this

information is sharedwith individuals theydo not know and over whom theyhave

no control? As individuals accept greater surveillance, close themselves within

gated communities, and support institutionsthatcommission security companies

towatch over employees, they end up doing exactly what the government and

security companies want them to do.

PuttingUp (with)Technology

Is the extensive use of security technology a sensible response to safety

problems in society, or is itbased on totalitarianism and irrational fear?Many

would claim that it is a logical reaction tounprecedented violence inU.S. society,

including random murders, school shootings and massacres, and terroristand

suicide bomber attacks.However, two aspects of security technology discussed in

this essay should cause us to pause and consider whether we should accept

unimpeded installation of security equipment in our society. The firsthas to do

with federal government support of security technologies. At a timewhen the

federal government has chosen to limitfunds to states, cut spending, and relinquish

itsduties inproviding a safetynet for thepoor and disenfranchised, itfindsuntold

sums of money and provides tax breaks for individuals who wish to purchase

security equipment. The second aspect has to do with theburgeoning business of

security and the lucrativemarket that ithas found in nearly every institutionand

public space inmodern life. The power of the security industry has become

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

92

Casella

concentrated inwhat Mills (1956) referred to as a power elite, a group comprised

of politicians, military officers, and corporate bosses.

The intentions of this power elite are only partly known. At some level,

politicians who support the installation of securityequipment are concerned about

thewelfare of individuals; yet, they are also interested in information gathering

and in testingand using new products under development. Federal agencies may

be using schools to test security equipment for later use by themilitary, for

domestic policing and crowd control, or for information-gathering on young

people, public housing occupants, those driving thehighways, individuals who

dress a certain way, or those who do not abide by all directives issued by the

political establishment.Who ismore paranoid: theperson who sees theneed for

all this security technology or the one who sees it as a form of totalitarianism?

Regardless of how one answers these questions, everyone should explore the

purposes behind this security buildup and refuse to accept simple answers about

safetyand protectionwhen there is littleevidence thatsecurity technology actually

makes

us

safer.

The longer a technology is used, themore entrenched in life itbecomes. When

technologies are new, or are used innewer ways (such as theapplication of satellite

technology to cellular phones), theiruses are easier tomodify and theirconse?

quences easier to control. The use of security technology in public places in the

form of biometrics, detectors, surveillance equipment, and advanced forms of

access control are relatively recent developments. If we wish to question the

unintended consequences of these developments, now is the time to do so. Too

little is known about the consequences of theuncontrolled use of these technolo?

gies, yet most policymakers support them due to their allure and short-term

promises of safety. If society becomes safer, if it becomes more difficult to

smuggle weapons into schools, or if violence decreases, advocates of these

technologies will claim that these are their intended consequences. However, if

public and private institutionsbegin to resemble prisons, ifnew generations begin

to accept unmitigated surveillance as a natural part of life, ifpeople's civil rights

become gradually revoked, or if people lose opportunities to develop human

relationships, such consequences must be viewed as intended as well.

REFERENCES

Beger, Randall

2002

Casella, Ronnie

2003

2001

"Expansion of Police Power in Public Schools

Students." Social Justice 29,1-2: 119-130.

and theVanishing

Rights of

"Security, Schooling, and the Consumer's Choice to Segregate." The Urban

Review 35,2: 129-148.

At Zero Tolerance: Punishment, Prevention, and School Violence. New York:

Peter Lang Publishing.

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The False Allure of Security Technologies

Col?ngridge,

1980

Devine,

93

David

John

1996

The Social Control of Technology. New York: St. Martin's

Security: The Culture of Violence

University of Chicago Press.

Maximum

Durbin, Paul

1989

Fickes, Michael

2000

Green, Mary

1999

Kennedy, Mike

2001

Philosophy

of Technology.

Press.

in Inner-City Schools. Chicago:

Boston: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

"Making theGrade with School Security." School Planning

39,4:3941.

and Management

inU.S. Schools:

The Appropriate and Effective Use of Security Technologies

Guide for Schools and Law Enforcement Agencies. National Institute of

Justice Research Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

"Security; Making Contact." American School and University (February 1): 1

3.

Kosar, John and Faruq Ahmed

2000

"Building Security into Schools." School Administrator 57,2: 2426.

Light, Michelle

2002

Scoop from theLoop. E-mail bulletin from theChildren and Family Justice

Center, Northwestern University Legal Clinic, m-light@law.northwestern.edu.

Lyon, David

1994

C. Wright

1956

Paeey, Arnold

1999

Postman, Neil

Mills,

The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance

ofMinnesota Press.

Society. Minneapolis:

University

The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meaning

in Technology.

Cambridge: MIT

Press.

Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Vintage

Books.

Scarbrough, Harry and J.Martin Corbett

1992

Technology and Organization: Power, Meaning, and Design. New York:

Routledge.

Sorrentino, Dominic

"A Whole New Paradigm: Changes inTechnology Have Altered the Face of

2002

School Security." American School and University 75: 4-6.

1992

Tenner, Edward

1996

Why Things Bite Back: Technology and theRevenge of Unintended Conse?

quences. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Townley, Arthur and Kenneth Martinez

toCreate Safer Schools." NASSP Bulletin 79,568: 6168.

1995

"Using Technology

Trump, Kenneth

The

"Scared or Prepared: Reducing Risks with School Security Assessments."

1999

6: 1823.'

High School Magazine

Wagman,

2002

Jake

"District Will Use Eye Scanning." The Philadelphia

Inquirer (October 24).

Retrieved June 20, 2003 at www.philly.com/mld/inquirer/living/education/

4355449.htm.

Weisberg, Dan

2000

"Scalable Hype: Old Persuasions forNew Technology." Robin Anderson and

Lance Strate (eds.), Critical Studies inMedia Commercialism. Oxford: Oxford

University Press: 186-200.

This content downloaded from 128.252.67.66 on Mon, 13 Jul 2015 21:02:53 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Cyber Security 1010001Document3 pagesCyber Security 1010001SamNo ratings yet

- Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy: A New Open Access JournalDocument3 pagesJournal of Cybersecurity and Privacy: A New Open Access JournalSamNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security 1010001Document3 pagesCyber Security 1010001SamNo ratings yet

- Asset Surveillance - Case StudyDocument10 pagesAsset Surveillance - Case StudyIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Internet of Things (Iot) : Smart and Secure Service Delivery: 1. BackgroundDocument7 pagesInternet of Things (Iot) : Smart and Secure Service Delivery: 1. BackgroundBayu PangestuNo ratings yet

- Cyber SecurityDocument22 pagesCyber SecuritySherwin DungcaNo ratings yet

- Identifying Vulnerabilities and Reducing Cyber Risks and Attacks Using A Cyber Security Lab EnvironmentDocument12 pagesIdentifying Vulnerabilities and Reducing Cyber Risks and Attacks Using A Cyber Security Lab EnvironmentIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Three Anti-Forensics Techniques That Pose The Greatest Risks To Digital Forensic InvestigationsDocument12 pagesThree Anti-Forensics Techniques That Pose The Greatest Risks To Digital Forensic InvestigationsAziq RezaNo ratings yet

- The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns Without Derailing InnovationDocument93 pagesThe Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns Without Derailing InnovationMercatus Center at George Mason UniversityNo ratings yet

- Information Security Challenge of QR CodesDocument32 pagesInformation Security Challenge of QR CodesnicolasvNo ratings yet

- A Study of Cyber Security Challenges and Developing Tendencies in The Latest TechnologiesDocument7 pagesA Study of Cyber Security Challenges and Developing Tendencies in The Latest TechnologiesIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Formato de Excel Modelo para Revision de LiteraturaDocument11 pagesFormato de Excel Modelo para Revision de LiteraturaJosué CNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3742516Document23 pagesSSRN Id3742516narashikamaru12pNo ratings yet

- Cyber 2Document13 pagesCyber 2FAS TechnicNo ratings yet

- Article Review: Student's Name Course Tutor's Name DateDocument6 pagesArticle Review: Student's Name Course Tutor's Name DateandyNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity in Supply ChainDocument10 pagesCybersecurity in Supply ChainOpen Access JournalNo ratings yet

- Digital Privacy Theory Policies and TechnologiesDocument3 pagesDigital Privacy Theory Policies and TechnologiesfloraagathaaNo ratings yet

- MIT Launches Three New Cybersecurity InitiativesDocument4 pagesMIT Launches Three New Cybersecurity Initiativesapi-282127104No ratings yet

- Experimental evaluation of cybersecurity threats to smart homesDocument4 pagesExperimental evaluation of cybersecurity threats to smart homesUsama NawazNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security in ManufacturingDocument9 pagesCyber Security in ManufacturingOpen Access JournalNo ratings yet

- Demystifying IoT Security - An Exhaustive Survey On IoT Vulnerabilities and A First Empirical Look On Internet-Scale IoT Exploitations PDFDocument32 pagesDemystifying IoT Security - An Exhaustive Survey On IoT Vulnerabilities and A First Empirical Look On Internet-Scale IoT Exploitations PDFTaghreed OoNo ratings yet

- Security and Ethical Issues in It: An Organization'S PerspectiveDocument13 pagesSecurity and Ethical Issues in It: An Organization'S Perspectiveadmin2146No ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S0040162523007138-mainDocument13 pages1-s2.0-S0040162523007138-mainGrace FournierNo ratings yet

- Internet Security Term PaperDocument7 pagesInternet Security Term Paperaflsqyljm100% (1)

- Literature Review Internet of ThingsDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Internet of Thingsafmzbdjmjocdtm100% (1)

- Lasya Muthyam Synthesis Paper 1Document29 pagesLasya Muthyam Synthesis Paper 1api-612624796100% (1)

- Experimental evaluation cybersecurity smart home researchDocument4 pagesExperimental evaluation cybersecurity smart home researchUsama NawazNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S004016252300001X MainDocument18 pages1 s2.0 S004016252300001X MainRamadhan Yudha PratamaNo ratings yet

- Social EngineeringDocument4 pagesSocial EngineeringkhonelloNo ratings yet

- Electronic Surveillance in Modern World Research PaperDocument6 pagesElectronic Surveillance in Modern World Research PaperoabmzrzndNo ratings yet

- Security and Privacy in Iot Using Machine Learning and Blockchain: Threats and CountermeasuresDocument37 pagesSecurity and Privacy in Iot Using Machine Learning and Blockchain: Threats and CountermeasuresTame HabtamuNo ratings yet

- 3 Iis 2020 142-152Document11 pages3 Iis 2020 142-152Spit FireNo ratings yet

- Biometrics in Banking Security A Case StudyDocument17 pagesBiometrics in Banking Security A Case StudyAnonymous tZJktxmHSNo ratings yet

- Paper CybersecurityDocument11 pagesPaper CybersecurityMohammad AliNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Securing The Internet of Things: Challenges, Threats and SolutionsDocument51 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Securing The Internet of Things: Challenges, Threats and SolutionsTú MinhNo ratings yet

- P24 butler-et-al-2023-the-regulation-of-and-through-information-technology-towards-a-conceptual-ontology-for-is-researchDocument22 pagesP24 butler-et-al-2023-the-regulation-of-and-through-information-technology-towards-a-conceptual-ontology-for-is-researchLingha Dharshan AnparasuNo ratings yet

- Ethical Hacking 1 Running Head: ETHICAL HACKING: Teaching Students To HackDocument37 pagesEthical Hacking 1 Running Head: ETHICAL HACKING: Teaching Students To Hackkn0wl3dg3No ratings yet

- I Am Here Privacy Aware SupportDocument14 pagesI Am Here Privacy Aware SupportIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Audit IT MateriDocument25 pagesAudit IT MateriAriel Maulana WibowoNo ratings yet

- Computer Science Security Research PaperDocument6 pagesComputer Science Security Research Papergpwrbbbkf100% (1)

- Cyber Security ResearchDocument9 pagesCyber Security Researchdagy36444No ratings yet

- Private Security Research PapersDocument7 pagesPrivate Security Research Paperscan3z5gx100% (1)

- Cyber Security Goes Beyond Information SecurityDocument6 pagesCyber Security Goes Beyond Information SecurityEslam AwadNo ratings yet

- Analysis Report On Attacks and Defence Modeling ApDocument10 pagesAnalysis Report On Attacks and Defence Modeling ApIchrak SouissiNo ratings yet

- The Ethical Application of Biometric Facial Recognition TechnologyDocument9 pagesThe Ethical Application of Biometric Facial Recognition Technologymaleksd111No ratings yet

- Security and PrivacyDocument8 pagesSecurity and Privacysteveparker123No ratings yet

- Computer Security and Impact On Computer Science eDocument15 pagesComputer Security and Impact On Computer Science eViva Vrumva HarazolaNo ratings yet

- Web Security DissertationDocument6 pagesWeb Security DissertationWriteMyCustomPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Information Security Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesInformation Security Thesis TopicsWriteMySociologyPaperAnchorage100% (2)

- Cyber SecurityDocument41 pagesCyber SecurityPeter thimbaNo ratings yet

- Cmanaois Blockchain FinalDocument20 pagesCmanaois Blockchain Finalapi-543686548No ratings yet

- Role of CCs in Cyber Ed-2002Document144 pagesRole of CCs in Cyber Ed-2002koledo7259No ratings yet

- A Game Theory Method To Cyber-Threat Information Sharing in Cloud Computing TechnologyDocument12 pagesA Game Theory Method To Cyber-Threat Information Sharing in Cloud Computing Technologyasusmaxprom177No ratings yet

- Holding On To Dissensus Participatory inDocument14 pagesHolding On To Dissensus Participatory inJuan SebastianNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch Proposalapi-612624796100% (1)

- Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Organizations: How to Bridge the Gap Between People and Digital TechnologyFrom EverandBuilding a Cybersecurity Culture in Organizations: How to Bridge the Gap Between People and Digital TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity in Digital Transformation: Scope and ApplicationsFrom EverandCybersecurity in Digital Transformation: Scope and ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security Meets Machine LearningFrom EverandCyber Security Meets Machine LearningXiaofeng ChenNo ratings yet

- The Five Technological Forces Disrupting Security: How Cloud, Social, Mobile, Big Data and IoT are Transforming Physical Security in the Digital AgeFrom EverandThe Five Technological Forces Disrupting Security: How Cloud, Social, Mobile, Big Data and IoT are Transforming Physical Security in the Digital AgeNo ratings yet

- Critical and Clinical Cartographies:: Architecture, Robotics, Medicine, PhilosophyDocument20 pagesCritical and Clinical Cartographies:: Architecture, Robotics, Medicine, PhilosophyAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Leper CreativityDocument310 pagesLeper CreativityNick AvramovNo ratings yet

- Leper CreativityDocument310 pagesLeper CreativityNick AvramovNo ratings yet

- Agam Ben Learning SocietyDocument15 pagesAgam Ben Learning SocietyerikclaipcenNo ratings yet

- Impact Defense 7WKDocument324 pagesImpact Defense 7WKAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Topicality UMKCDocument55 pagesTopicality UMKCAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Able NormativeDocument106 pagesAble NormativeAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- CyclonopediaDocument262 pagesCyclonopediaAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Epstein, Guilty Bodies, Productive Bodies, Destructive Bodies PDFDocument16 pagesEpstein, Guilty Bodies, Productive Bodies, Destructive Bodies PDFAndrea TorranoNo ratings yet

- Bhud KDocument1 pageBhud KAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Ukraine DipCapDADocument3 pagesUkraine DipCapDAAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Kritik Answers A-E (Michigan)Document398 pagesKritik Answers A-E (Michigan)Achal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Afro-Pessimism - Gonzaga 2014Document93 pagesAfro-Pessimism - Gonzaga 2014Achal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Nuclear War Impact CoreDocument59 pagesNuclear War Impact CoreAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- A2 Wilderson KDocument6 pagesA2 Wilderson KAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- States CP Solves WarmingDocument112 pagesStates CP Solves WarmingAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Foucault & Virilio - UTNIF 2012 - PaperlessDocument167 pagesFoucault & Virilio - UTNIF 2012 - PaperlessAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Utnif 2012 Oil DaDocument167 pagesUtnif 2012 Oil DaAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- FrappRussell 3 K Answers ToolboxDocument200 pagesFrappRussell 3 K Answers ToolboxAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Framework File Six Week ENDI 2010-1Document96 pagesFramework File Six Week ENDI 2010-1Ram PrasadNo ratings yet

- Chinese Air Zone DADocument48 pagesChinese Air Zone DAAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Waves 1ACDocument12 pagesWaves 1ACAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Toursim Da Answers 2acDocument7 pagesToursim Da Answers 2acAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Framework - Berkeley 2013Document128 pagesFramework - Berkeley 2013Achal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Aff FrameworkDocument21 pagesAff FrameworkKavi ShahNo ratings yet

- Kritik Answers and Framework - UNT 2013Document86 pagesKritik Answers and Framework - UNT 2013Achal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Warming TurnsDocument15 pagesWarming TurnsAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Steel DADocument5 pagesSteel DAAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- Asia Pivot Answers 2acDocument27 pagesAsia Pivot Answers 2acAchal ThakoreNo ratings yet

- 02 Components of Financial PlanDocument23 pages02 Components of Financial PlanGrantt ChristianNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court upholds damages for passenger forced to give up first class seatDocument8 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court upholds damages for passenger forced to give up first class seatArmand Patiño AlforqueNo ratings yet

- NAstran Simple Problems Getting StartedDocument62 pagesNAstran Simple Problems Getting StartedAvinash KshirsagarNo ratings yet

- USA V Peter G. MoloneyDocument22 pagesUSA V Peter G. MoloneyFile 411No ratings yet

- Mathcad CustomerServiceGuideDocument13 pagesMathcad CustomerServiceGuidenonfacedorkNo ratings yet

- Art. 779. Testamentary Succession Is That Which Results From The Designation of An Heir, Made in A Will Executed in The Form Prescribed by Law. (N)Document39 pagesArt. 779. Testamentary Succession Is That Which Results From The Designation of An Heir, Made in A Will Executed in The Form Prescribed by Law. (N)Jan NiñoNo ratings yet

- Lincoln's Yarns and Stories: A Complete Collection of The Funny and Witty Anecdotes That Made Lincoln Famous As America's Greatest Story Teller by McClure, Alexander K. (Alexander Kelly), 1828-1909Document317 pagesLincoln's Yarns and Stories: A Complete Collection of The Funny and Witty Anecdotes That Made Lincoln Famous As America's Greatest Story Teller by McClure, Alexander K. (Alexander Kelly), 1828-1909Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Gmail - Your Booking Confirmation PDFDocument8 pagesGmail - Your Booking Confirmation PDFvillanuevamarkdNo ratings yet

- QUAL7427613SYN Cost of Quality PlaybookDocument58 pagesQUAL7427613SYN Cost of Quality Playbookranga.ramanNo ratings yet

- Money Bee PVT LTDDocument3 pagesMoney Bee PVT LTDKishor AhirkarNo ratings yet

- Agra MCQDocument4 pagesAgra MCQDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Mrs. Shanta V. State of Andhra Pradesh and OrsDocument12 pagesMrs. Shanta V. State of Andhra Pradesh and OrsOnindya MitraNo ratings yet

- Christian Biblical Church of God & Fred Coulter Comparison Expose'Document23 pagesChristian Biblical Church of God & Fred Coulter Comparison Expose'Timothy Kitchen Jr.No ratings yet

- List 2014 Year 1Document3 pagesList 2014 Year 1VedNo ratings yet

- MMDA Bel Air Case DigestDocument2 pagesMMDA Bel Air Case DigestJohn Soliven100% (3)

- CopyofbillcreatorDocument2 pagesCopyofbillcreatorapi-336685023No ratings yet

- Cost 2023-MayDocument6 pagesCost 2023-MayDAVID I MUSHINo ratings yet

- Apostolic Fathers & Spiritual BastardsDocument78 pagesApostolic Fathers & Spiritual Bastardsanon_472617452100% (2)

- Transportation Law ReviewerDocument34 pagesTransportation Law Reviewerlengjavier100% (1)

- 33 Dale Stricland Vs Ernst & Young 8 1 18 G.R. No. 193782Document3 pages33 Dale Stricland Vs Ernst & Young 8 1 18 G.R. No. 193782RubenNo ratings yet

- South Carolina Shooting Hoax Proven in Pictures NODISINFODocument30 pagesSouth Carolina Shooting Hoax Proven in Pictures NODISINFOAshley Diane HenryNo ratings yet

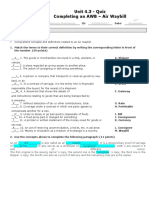

- 1DONE2. CX Quiz 4.3 - Air WaybillDocument1 page1DONE2. CX Quiz 4.3 - Air WaybillProving ThingsNo ratings yet

- GAD and GST WebinarDocument3 pagesGAD and GST WebinarAllan IgbuhayNo ratings yet

- Sample Letter Termination of Employment On Notice For Poor Performance Preliminary DecisionDocument2 pagesSample Letter Termination of Employment On Notice For Poor Performance Preliminary DecisionEvelyn Agustin BlonesNo ratings yet

- DBP v. BautistaDocument1 pageDBP v. BautistaElla B.No ratings yet

- ECG-CE Comen PDFDocument3 pagesECG-CE Comen PDFTehoptimed SA0% (1)

- Publish Your Documents Upload Documents: Unlock Your Documents by Putting Them On ScribdDocument18 pagesPublish Your Documents Upload Documents: Unlock Your Documents by Putting Them On Scribdm.bakrNo ratings yet

- (Database & ERP - OMG) Gaetjen, Scott - Knox, David Christopher - Maroulis, William - Oracle Database 12c security-McGraw-Hill Education (2015) PDFDocument549 pages(Database & ERP - OMG) Gaetjen, Scott - Knox, David Christopher - Maroulis, William - Oracle Database 12c security-McGraw-Hill Education (2015) PDFboualem.iniNo ratings yet

- TYBMS BLACK BOOK LISTDocument1 pageTYBMS BLACK BOOK LISTDhiraj PalNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (S&R (P&B) Section)Document3 pagesMinistry of Road Transport & Highways (S&R (P&B) Section)mrinalNo ratings yet