Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Discourse Conditions For The Use of The

Uploaded by

Motochika YamashitaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Discourse Conditions For The Use of The

Uploaded by

Motochika YamashitaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal or Pragmatics 15 (1991) 237-251

NorthHolland

237

The discourse conditions for the use of the

complementizer that in conversational English

Sandra A. Thompson and Anthony Mulac

Receiled March 1989: relised l'ersion February 1990

The complementizer that iil English, as in I heard (that) you were sick, has wirlely been regarded

as optional. Our reseaiCh demonstrates that the use of that in such utterances in conversation is

highly related to various other features in the discourse. First and second person subjects. the

verbs think and guess, and auxiliaries, indirect objects, and adverbs in the main clause, and

pronominal complement subjects are all significant in predicting the use of that. As seemingly

disparate as these factors are, their influence finds a unified explanation in the acknowledgement

that certain combinations or main clause subjects and verbs in English (such as I think) are being

reanalyzed as unitary epistemic phrases. As this happens, the distinction between 'main' and

'co'.llplemenf clauses is being eroded, with th<; omission of ihat a strong concomitant. Our

findings show that the factors most likely to contribute to this reanalysis are precisely those which

relate either to the epistemicity of the main subject and verb or to the topicality of the complement

at the expense of the main clause.

1. Introduction and background

It is well known that the complementizer that is omissible in English. Two

examples from our data illustrate this~ (I) below has that, while (2) does not:

(1) I mean like. my little sister, you can tell that she'!' growing up so much

faster than I did. (26.89)

(2) I heard 0 your food's a lot better than our food.

(25.163) 1

Authors' address: S.A. Thompson, Dept. of Linguistics, and A. Mulac. Dept. ofCommunica

tion. University of California, Santa Barbara. CA 93106. USA.

W-: would like to thank the following people for helpful comments on earlier versions of this

paper: Dwight Bolinger, Joan Bybee, Wallace Chafe. Simon Dik. John Du Boi:i, Mark Durie,

Julie Gerhardt. David Hargreaves, Paul Hopper, C. Douglas Johnson, Ronald Macaulay.

Tsuyoshi Ono, William Pagliuca. Gisela Redeker, Nathan Salmon, Janine Scancarelli. Arthur

Schwartz, Dan Slobin, R. McMillan Thompson. and Elizabeth Traugott. None of these people

necessarily agrees with the interpretation we've given to their input. We also appreciate Bonnie

Seligmann's and Yuka Koide's excellent senior essays on this topic.

1

The numbers in parentheses indicate dyad number and line number in our data base (see

section 2. Methodology. below).

03782166/91/$03.50

1991 -

Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. (North-Holland)

238

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac/ Discourse uses of that in English

Most traditional and modern formal approaches to English have taken the

view that this omissiblity represents an option for speakers of English, but

relatively few have concerned themselves with determining what the conditions underlying its appearance might actually be.

Our purpose in this paper is to refute the absolute optionality of this

alternation, and to show that, in probabilistic terms, there are very dear

conditions underlying the decision to use or to vmit the complementizer that

in ordinary talk. We will compare our findings to earlier studies on the use of

that in written English.

We are not the first to propose explanations for the fact that the complementizer that is sometimes missing and sometimes present. The work of

Dwight Bolinger challenged the idea of 'optional' 'rules' almost as soon as this

concept appeared in the writings of grammarians oriented towards transformational descriptions. Thanks in large part to his efforts. it is now widely

accepted that what had been thought of as 'stylistic options' are better seen as

genuine choices of the speaker based on such factors as attitude, emotional

stance, information flow, and discourse structure.

Bolinger (I 972) suggested that the choice of whether to use or not use a

complementizer that is likely to be determined in large part by considerations

involving subconscious factors such as the attitudes of the subject of the main

v~rb towards the content of the complement clause and the extent to which its

content is known information.

Three studies have investigated the question of the alternation between

complementizer that and its omission for written English. McDavid ( 1964),

using a corpus of modern non-fiction, concludes that "the conditions under

which that may be omitted seem partly stylistic and partly grammatical,,

(p. I 13 ). Elsness (1984) considers the alternation across several genres, and

concludes that "the conditioning process governing the choice of connective

[i.e., that or 'zero - ST & AM] in English object clauses is more complex than

has usually been acknowledg("d'" (p. 533). According to him, a number

of factors are involved. including style, potential ambiguity, structural

complexity. weight, and closeness of clause juncture.

U nderhilt (I 988) is the first to relate the use of that to the relationship

between the main' verb and the 'complement'. Emonds {1969, 1976); Hooper

and Thompson (1973), and Hooper (1975) had observed that the operation of

'complement preposing', as illustrated in (3a) and (3b), is determined by the

semantics of the 'main' verb. 2

2

Emonds' term 'complement preposing', was introduced at a time when grammatical phenomena tended to be described in terms of metaphors involving movement from one part of a

structural diagram to another. In (3b), of course, as pointed out by Emonds, the erstwhile

complement takes on the role of an independent assertion and the erstwhile main clause becomes

a tag.

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac I Discourse uses of that in English

(3a) I believe it's going to snow.

(3b) It's going to snow, I believe.

239

(complement preposed)

These studies point out that this alternation is possible only with certain

verbs, those whose meaning has essentially been "bleached' to the point where

the phrase acts as an adverbial. We will call the use of a subject and verb

phrase illustrated in (3b) its parenthetical use, after Emonds '1969) and

Urmson (1963).

Halliday (1985) suggests that the epistemic sense of subject+ verb phrases

as in (2) is in a metaphori;al relationship with the main verb use, the

metaphor ..functioning as an expression of modality" (p. 332). He also notes

certain arguments for the reanalysis cited in Emonds and in Hooper and

Thompson, including the argument that the tag agrees with the apparently

embedded clause, rather than with the apparently main subject and verb:

(4) I think ifs going to rain, isn't it? (*don't I?)

Underhill (1988) is also the first to demonstrate that the use of that is

related to discourse structure; his research provided the inspiration for the

study we are reporting here. He makes a strong case in favor of the following

partially overlapping hypotheses for journahstic English:

(a) That is deleted when the subject of the lower sentence is the topic of

the utterance; that is retained when the subject of the higher sentence is the

topic.

(b) That is deleted when the writer makes or endorses the assertion of the

lower sentence; that is retained when the writer does not (necessarily) endorse

the assertion, but attributes it to someone else. In such a case the speaker may

deny the assertion, doubt it, evade responsibility, or simply be noncommittal.

Underhill is thus claiming that these discourse facts can be accounted for in

terms of his hypothesis: where the embedded clause loses much of its

embeddedness, its subject, rather than the main clause subject, tends to be the

topic of the discourse, and its content, rather than that of the main clause.

tends to be what the writer is endorsing. The main clause subject and verb,

then, become secondary to the content of the lower sentence. which the writer

endorses, and to the subject of the lower sentence, which is the topic.

We would suggest that this line of reasoning can be taken one step further:

these bleached-out main verbs and their subjects behave very much like single

epistemic morphemes in other languages, to the point of being 'transportable'

240

S . A . Thompson . .4 . .\fu/ac

D iscourse IL~es ~(that in English

to pos1ttons other than that which they could occupy if they were only

functioning to introduce a complement. as is shown in (3b). 3

Our study of the use of that moves away from written English to consider a

large data base of spoken conversational English. In addition. we have

employed a quantitative methodology. which reveals patterns of use not

found by earlier researchers.

2. !\-lethodology

The transcripts analyzed for this study come from . '6 &-minute recorded

conversations between university students at the University of California.

Santa Barbara. For the purposes of a separate ~eries of studies (see. e.g..

Mulac et al. 1987). each student was randomly paired with two individuals he

or she did not know well. creating a mixed-sex and a same-sex dyad. In this

way. 58 male/female. 29 male/male, and 29 female/female dyads were formed.

They were asked to discuss at least one of several topics provided them.

such as 'What should be the University's policies on drug/alcohol abuse?'

and 'What are the advantages and disadvantages of a liberal arts education?'

The recordings were transcribed orthographically and verified by trained

observers. A computerized word count showed that the nearly 151/i hours of

conversation resulted in mure than 240.000 words spoken.

The first author analyzed the transcripts for instances of the target

construction. with or without that. 4 The second author provided a reliability

check by independently coding 20% of the transcripts. The point-by-point

percent of agreement between the two of us was 97%. In all, 1287 instances of

the target form were iden Lified and coded for selected parameters.

These parameters included the following:

(a) whether or not a that occurred;

(b) whether or not the main clause contained an auxiliary, an adverb, an

indirect object. or a passive, or was an interrogative or a negative~

(c) whether or not the complement subject was a pronoun or was co-referential with the main clause subject.

What we considered to be the target construction, then, were all occurrences of main' subject and verb. as in (I) and (2), which could occur with that,

whether or not the that was present. We also counted and coded separately all

epistemic parentheticals, as in (3).

3

For discussion of the grammaticization of epistemic parentheticals. see Thompson aod Mulac

(in press).

4

We are using the term 'target construction' simply to refer to the 'construction in question.

S . A. Thompson , A. Mulac I Dismurse uses of that in English

241

Because of theif function as pragmatic expressions. 5 we did not count

occurrences of you know or I mean, as in:

(5) An' I'll get everything accomplished and this and that and I may even do

good. You know but it's just all the work that you realize that you have to

do before Monday morning at 8 o'clock. (14.375)

(6) B: Food's terrible, huh?

A: Well, it's not actually that bad. It all depends on your, on your taste. I

mean, how well, what youre used to I mean you're used to really fine

cuisine at home you're not going to be able to tolerate dorm

food. (15.31)

3. Terminology

For the remainder of this paper, we will refrain from using the term thatdeletion' because it connotes an inappropriate processual metaphor. For ease

of reference, we will continue to refer to main' and 'complement' clauses

without quotation marks. These should be taken as simply mnenomic labels.

however, as our central point is that the blurring of the distinction between

main' and complement' clause is precisely what is involved in creating the

conditions which are giving rise to epistemic parentheticals. When we use the

terms subject' and 'verb', we \'ill be referring to the main' clause subject and

verb, not the 'complement' clause subject and verb. As mentioned above, we

will use the term 'targ :.:t' to refer to subjects ahd their verbs in pre-complement

positions, with or without that (illustrated by (I) and (2)), where they can be

analyzed as introducing the complement.

The term 'verb type' will occasionally be used in implicit opposition to verb

token'.

0

4. Results and discussion

Our findings from conversational English strongly support Underhill's hypothesis from newspaper English that the use of the complementizer that is

correlated with the degree of 'embeddedness' of the complement clause. That

is, when there is no that, the main clause subject and verb function as an

epistemic phrase, not as a main clause introducing a complement.

We will support this claim by showing that:

5

For discussions of such discourse particles in conversation. see Goldberg !980; Ostman 1981 ;

Schourup 1985; Erman 1986; and Scbiffrin 1987.

S . A. Thompson. A. Mulac / Discourse uses of that in English

242

( 1) the most frequc.1t main verbs and subjects are .1.tst those which typically

occur without that, and which are characteristically associated with epi:;temicitv '

(2) a pronominal subject in the complement clause, which is an indication of

the topicality' of that subject in the discourse, also tends to occur without

that, as suggested by Underhill's results;

(3) other elements in the main verb phrase, such as adverbs, which reduce the

likelihood that the subject and verb are functioning as an epistemic

phrase, ~gn Jicantly favor the use of that.

Our most striking finding is that the use of that is strongly related to the u~

of various other elements in the utterance, as described in the discussion of

methodology above. An overail chi-square analysis supports our contention

of differences in the use of that depending of the presence of these eight

elements (chi-square (7, N = 1287) = 79.77, p < 0.0001). With this

result as the warrant for further analyses, we will consider each of these in

turn.

4.1. Subjects

Table l shows that there is a much greater likelihood of omitting that when

the main .subject is I or second person you than when it is any other

subject. 6

Table I

Occurrence of that with I vs. you vs. other subjects.

- that

955

you

other

55

102

Total

+that

(90%)

(91%)

(64%)

Chi-square (2. N

110

(IO%)

1065

(9%)

(36%)

61

59

= 1287) = 79.19, p

161

(100%)

(100%}

(100%)

< 0.0001

Table 2 shows that I and you are also the subjects occurring with the highest

frequency in the data.

These tables make is clear that the most frequent subjects in our data are

also used most frequently without that.

6

Our coding distinguishes second person you from generic you. From here on, whenever you is

mentioned, we mean second person you ; generic you is included in the 'other' category.

S. A . Thompson , A. Mulac/ Discourse uses of that in English

243

Table2

The most frequent subjects with main verbs.

you 2p

other

!065

61

151

(83%)

(5%)

(12%)

Total

1287

(100%)

Interestingly, as has often been noted, these are also the subjects which can

express epistemicity, or degree of speaker commitment (Palmer 1986: 51;

Traugott 1987). A number of researchers have pointed out that speaker

commitment can only be asserted for the speaker by the speaker (/), or

queried of the addressee by the speaker (you). It cannot be meaningfully

asserted or queried about a third person.

For example, Woodbury (1986 : 192), in a discussion of evidentiaiity in

Sherpa, points out that:

"The first person vs. nonfirst person distinction is widespread in Sherpa, hut the term 'first

person' is something of a misnomer. In the interrogative all so-called first person phenomena are

associated with second person." (emphasis added [ST & AM))

In his discussion of subjectivity in language, Benveniste (1971 : 228- 229)

notes that certain verbs do not have the property of permanence of meaning" when the person of the subject is changed : in particular, verbs of ..mental

operations", such as believe, when used with / , ..convert into a subjective

utterance the fact asserted impersonally".

Similarly, in his discussion of 'parenthetical verbs' in English, Urmson

(1963: 222) notes:

Part of what I design to show is how d:fferently these verbs (i.e., what he calls 'parentheticai'

verbs. e.g . think and believe - ST & AM) are used in the first person present and in other persons

and tenses."

Neither Benveniste nor Unnson consiaered interrogative you with the verbs

in question, but our data suggest that it fom1s a class with I in the present

tense, and that the two together must be distinguished from all other persons

and tenses.

In our data, 55 out of 67 (82%) of the target clause you's are in questions.

In the examples below, using intonation as the criterion, 7 (7) illustrates a

target clause question, and (8), just for comparison, i11ustr~tes a tar~~ clause

you which is not a question:

We follow the standard transcription practice of indicating rising intonation with a question

mark and falling intonation with a period.

7

244

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac ; Discourse uses of that in English

(7) So what do you think youre going to major in now that you're down

here? ( !08.133)

(8, l calking about dormitory regulations on alcohol)

A: ... they probably shouldn't have any rules at all but

B: [(laughs) you think it should be wide open.] 8

A: [If they're legally responsible] (95.274)

So the fact that I and you. the subjects which can express epistemicity, are

the most frequent main clause subjects is a strong factor favoring the

reanalysis of these main subjects and their verbs as epistemic phrases.

4.2. Verbs

A very similar situation exists for main verbs in our data. The most frequently

occurring verbs in the data are also those occurring most frequently without

that, and they are also verbs heavily involved in the expression of epistemicity.

Table 3 indicates that think and guess (in the present tense) also occur

significantly more frequently without that than any other verb in the data

base. 9

Table 3

Occurrence of that with think vs. guess vs. all other verbs.

- thac

think

guess

other

622

148

342

+that

(91%)

(99%)

(76%)

61

2

112

Total

(9%)

(1%)

(24%)

683

150

454

(100%)

(100%)

(100%)

Chi-square (2. N = 1287) = 79.24, p < 0.0001

Table 4 shows the relative frequency of verbs; think and guess far outnumber

any other verb in the data. Altogether there are 44 different target verb types

in our data; it is striking that think and guess account for 65% of all the target

verb tokens, while the other 42 verbs are spread over the remaining 35%_

Once again. it is no accident that the~e most frequent verbs, think and

guess. are highly epistemic verbs, expressing a mild degree of speaker commitment. They are not the only ;erbs in t.he data which express speaker

Our tran~cription system uses brackets to indicate overlapping or simultaneous portions of

utterances.

<i

Not only is the three-w _y comparison significant at the level of p < 0.001, but chi-square pairwise comparisons also show that think and guess are each significantly more likely (at the level of

p < 0.001) to occur without that than is the complement set of all other verbs.

8

S.A. Thompson. A. Mulac / Discour.1e

u.H' S

o/that in Englisli

245

commitment. but it is significant that the verbs occurring most frequently

without that are epistemic. 10

Table4

The most frequt>nt main verbs out of 44 main verb types.

think

(53%)

guess

other

683

150

454

(35%)

Total

1287

(100%)

(12%)

}65%

4.3. Elements of the main clause

As indicated above in our methodology discussion, we considered a range of

main clause variables which we hypothesized might predict the occurrence of

that. The variables can be divided into two groups. motivated by two different

hypotheses.

4.3.l. Group I: Interrogation and negation

Considering interrogation and negation as variables was motivated by the

hypothesis that the use of that is correlated with the greater syntactic

complexity of an interrogative or negative verb phrase. This hypothesis was

not supported by chi-square analyses ; neither of these variables was significant in predicting the use of tlzat. 11

4.3.2. Group II: Other main clause elements

As mentioned in the discussion of our methodology, in addition to interrogation and negation, we also considered the following main clause verb phrase

elements:

auxiliaries

passive morphology

adverbs

indirect objects

Dwight Bolinger and Gillian Sankoff have pointed out to us that the nature of our data base,

conversations in which speakers were expressing opinions. may have influenced the proportions of

verbs used. One might have expected more occurrences of beheie. bet , figure, or suppose in other

conversations. for example. We acknowledge this possibility. but note that our hypothesis is

strongly confirmed by the fact that the two verbs which are far and away the most frequent in the

data base are both highly epistemic and arc found significantly more often without that than the

other verbs in the data base.

11

In section 4.1 we showed that you in interrogatives was a predictor of the absence of that. The

failure of interrogatives to be significant in predicting the occurrence of that is not inconsistent

with this finding; the chi-square analysis simply shows that interrogatives and declaratives do not

differ significantly in their ability to predict the occurrence of that. We hypothesize that this is

because I in declaratives is as likely to occur without that as you in questions is.

10

S.A. Thompson, A. M'.4/ac /Discourse uses of that in English

246

The rationale for considerinr- these variables was our hypothesis that any of

these elements reduces the ability of the main clause subject and verb to

function as an epistemic phrase, since they each add semantic content to the

verb phrase qua main verb phrase, and thereby reduce the likelihood that that

verb phrase could be taken as an epistemic phrase.

This hypothesis was strongly supported; all these variables predict the use

of that to a significant degree, except for passive, of which there were only two

instances. We will discuss each of the others in turn.

In this category we included any example containing

either a modal or the auxiliaries have or progressive be. 12 (9) is an example

with the modal should:

4.3.2.1. Auxiliaries.

(9) (talking about the perception that Californians know a lot of movie stars)

... people who should know you know that you don't just walk down the

street aad shake hands with them. (63.249)

An example of a main verb with the progressive be from our data base is

given in ( lO):

(I 0) .. . he was saying that by the year 2000 there's, there will be, we will, the

Caucasians, or the whites will be a minority as far as in California

(60.312)

Table S shows that utterances whose main \erb phrases contain auxiliaries

are significantly more likely to occur with that than those which do not. Verb

phrases with auxiliaries occur with that 27.5% of the time, but verb phrases

without auxiliaries c~cur with that only 12.5% of the time.

Table S

Occurrence of that with and without auxiliary.

-that

With auxiliary

Without auxiliary

86

1026

+that

(71.l %)

(88.0%)

Chi-square (l, N

35

140

= 1287) = 26.81, p

Total

(28.9%)

(12.Uo/o)

121

1166

(100%)

(100%)

< O.OOOi

In this category we included any mam clause

containing a noun phrase playing a recipient or beneficiary semantic role

coming directly after the verb, as exemplified in (1 l):

4.3.2.2. l11direct objf'cts.

12

We did not include examples with the passi'Ve he since we wished to consider passives

separately.

S.A. Thompson. A. Mulac I Discourse use.~ of that in English

(11) I wanted to show her thac i . she got the points.

247

(8.257)

As can be seen in table 6, verb phrases with indirect objects occur with that

53.3% of the time, wher::.!s verb phrnses without indirect objects occur with

that only 13. l % of the time. 13

Table6

Occurrence of that with and without indirect object.

-thal

With ind. obj.

7

Without ind. obj. II 05

+that

(46.7%)

(86.9%)

8

167

Total

(53.3%)

(13.1%)

15

1272

(100%)

(100%)

Chi-square (I. N = 1287) = 20.4. p < 0.0001

4.3.2.3. Adverbs. The situation with adverbs is very similar. An example of

an adverb in the main verb phrase is given in (12):

(12) Uh, I just figurt!d that I'd walk to ciass at that time. just stay m the

library . . . (68.473)

Table 7 shows that main verb phrases with an adverb (such as just or only)

occur with that 35% c-f the time, while main verb phrases without adverbs

occur with that only i 2, ?.% of the time. 14

Table 7

Occurrence of that with and without adverbs.

-that

With adverbs

Without adverbs

52

1060

Total

+that

(65%)

(87.8%)

Chi-square (I, N

28

147

= 1287) =

(35%)

(12.2%)

80

1209

(100%)

(100%)

33.26, p < 0.0001

4.3.3. Summary of main clause variables

We have seen that certain main verb elements. namely auxiliaries, indirect

objects, and adverbs, significantly increase the use of that to introduce the

complement. This fact can be explained if we hypothe~i?.e that the more likely the

Here the dependence amcng our variables does appear to play a role. The results in tables 5

and 6 are undoubtedly influenced by the fact that think and guess, in the relevant usages, do not

take indirect objects and typically do not occur in the progressive.

H

Simon Dik has suggested to us that some adverbs, such as personally or strongly would in fact

seem to remforce, rather than weaken, the epistemic force of the utterance. and hence should be

expected to occur with greater absence, rather than presence, of that. It is possible that this is so,

but the verb phrase adverbs in our data base consisted almost entirely of qualifying, intensifying,

and hedging adverbs such as just, really, and kind of

13

248

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac/ Discourse uses of that in English

main subject and verb are to be taken as a unitary epistemic phrase, the less likely

is that to occur. All these erb phrase elements reduce the likelihood that the

main sul:>ject and verb are being used as an epistemic phrase; their presence

correlates with a literal use of the subject and verb as independent lexical items.

4.4. Complement subject

So far, we have considered main clause elements which are relevant in the use

of that. We have seen that the main clause subject, the main clause verb, and

other elements of the main verb phrase play a role. Intriguingly. the choice of

complement subject also figures in the use of that. When the complement

clause subject is a pronoun, that is less likely to be used than when it is a full

noun phrase. as shown in table 8.

Table 8

Occurrence of that with complement subject full NP vs. pronoun.

- that

Full NP

Pronoun

205

861

Total

+that

(79.2%}

(88.9%}

Chi-squar~ (i,

54

108

(20.7%)

(l l.1%)

259

969

(100%)

(100%)

= i287) = i6.81, p < D.0001

As table 8 indicates, whe::i the compiement subject is a fuli noun phrase, that

occurs 20.7% of the time, but when the complement subject is a pronoun, that

is used only 11.2% of the time.

Why should this be so? Recall that UnderhiH's hypothesis(a) above predicts

that that will tend to be 'omitted' in journalistic written English when the

subject of the complement clause is the topic of the discourse. Our findings

bear out this prediction for conversational English, since pronouns indicate

high discourse topicality.

Our findings and Underhill's have the same explanation. In Underhill's

data from newspaper En~iish, complement subjects which are topics of the

discourse tend to occur without that. In our data, pronominal complement

subjects (which can be considered topical by virtue of being pronouns) tend to

occur without that. These two facts can both be explained, once again, if we

assume that the reanalysis of main subject and verb as an epistemic phrase

correlates with the topicality of the complement subject in the discourse. The

more the main clause subject is taken as part of a unitary epistemic phrase,

the more likely is the complement subject to be the discourse topic.

4.5. Summary of results

In this section, we have seen that the use of complementizer that is highly

S.A. Thompson. A. Mulac I Discourse uses of that in English

249

related to the use of various other features of the discourse. First and second

person subjects. the verbs think and guess. pronominal complement subjects,

and auxiliaries, indirect objects, and adverbs are significant in predicting the

use of that. As seemingly disparate as these factors are, their behavior finds a

unified explanation in the acknowledgement that certain combinations of

main clause subjects and verbs in English are being reanalyzed as unitary

epistemic phrases. As this happens, the distinction between main' and

complement' clause is being eroded, as suggested by Emonds and Underhill,

with the omission of that a strong concomitant. That is. the more the main'

subject and verb are taken as an epistemic phrase, the less the complement' is

taken as a complement\ and the less likely is the complementizer that to be

used.

Our analyses have shown that the factors most likely to contribute to this

reanalysis are precisely those which relate either to the epistemicity of the

main subject and verb or to the topicality of the complement at the expense of

the main clause. As we have seen, the frequency of the subjects I and you and

the verbs think and guess provides a strong push towards the reanalysis

because these are just the subjects and verbs most likely to express epistemic

meanings: speakers assert speaker commitment with I or question it with you,

and think and guess express a mild degree of speaker commitment.

Before turning to our conclusions, we would like to address one objection

which might be raised at this point. Readers might wonder whether each of

the variables discussed in this section independently influences the occurrence

of that. That is, in assessing the role of a given variable, should we not also

control for the possible influence of another co-occurring variable?

In an attempt to determine the answer to this question. we created a

modified data base consisting of those utterances which contained only one of

the variables we have discussed. That is, if an utterance contained two or

more of the variables, for example, a modal aud a negative morpheme, it was

not included in the modified data base. The result of this cteansing' process,

however, was to <.!ate a modified data base containing only about 20% of

the data. In other \\'ords, the great majority of the utterances in our originai

data base contain more than one of the variables we have considered.

The modified data base showed tendencies in the predicted direction, but

only three of the variables influenced the use of that to a significant extent, as

determined by chi-square tests. 15

This exercise raises an intriguing methodological question: do we learn

more about the phenomenon we are investigating if we report findings from a

greatly diminished data base in which variables are considered strictly independently, or do we learn more if we report findings from a full data base

15

These three were auxiliaries', 'adverbs', and indirect objects; these were all significant at p

< 0.05, with chi-square values greater than 5.00 (Ns < 260).

250

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac/ Discourse uses of that in English

with variables confounded such that it is indeterminate which one is responsible for the occurrence of that?

The goals of this study strongly motivate us to favor the latter option. That

is, as stated at the outset, we seek to refute the claim that the use of that in

conversational English is random or optional', and to ascertain the conditions under which that is used. We are thus interested in predictors of that.

rather than in causes. The evidence clearly supports our claim that the use of

that is not random, and that the conditions influencing its use include the

person of the main clause subject. whether the verb is think or guess, the

presence of one of the main clause variables we have considered, and whether

the complement subject is a pronoun. Given that we are not interested in

determining a unique factor which determines the use of that, we are free to

utilize a methodology which does not insist on controlling for interaction

among variables.

5. Conclusions

As we attempt to understand why grammatical patterns work the way they do,

we must look to the way language is used by speakers in ordinary conversation.

Our study of the apparently random use of the 'complementizer' that in

English illustrates this in two ways.

From a methodological point of view, it is crucial to note that speakers are

entirely unaware of the factors influencing their own use of that. This means

that attempts to understand the grammar of the use of that cannot be based

on speakers' judgments about when they use that or what sentences with or

without it mean.

But even more important, it is only when we look at naturally-occurring

discourse, specifically conversational discourse, that we can see distributional

patterns which directly bear on the question of how the grammatical patterns

we are interested in come about. As Du Bois (1985) has put it, "grammars

code best what speakers do most". That is, grammatical patter!ls tend to be

isomorphic with discourse patterns (Du Bois 1987), and this is entirely

natural, since the particular set of subsystems which we think of as 'grammar'

can only arise from patterns in the way language is used by speakers. 16 Our

findings confirm this view of grammar as discoursedependent in the strongest

possible way. The factors determining the use of that have exclusively to do

with such discourse aad interactional parameters as expression of epistemicity

and topic. Neither the grammatical 'optionality' of that nor the grammatical

categorial blurring of the distinction between 'main' and 'embedded' clause

make any sense unless we take into account the patterns in the way speakers

express epistemicity and topic management in discourse.

16

For discussion of the 'emergence' of grammar from discourse, see Hopper (1987, 1988).

S.A. Thompson, A. Mulac I Discourse uses of that in Ergl1sh

251

References

Bolinger, Dwight, 1972. That's that. The Hague: Mouton.

Caton, Charles E .. ed., 1963. Philosophy and ordinary language. Urbana, IL: University of

Illinois Press.

Du Bois, John W., 1985. Competing motivations. In: J. Haiman, ed., 1985, pp. 343-365.

Du Bois, John W., 1987. The discourse basis of ergativity. Language 63: 805-855.

Elsness, Johan, 1984. That or zero? A look at the choice of object clause connective in a corpus of

American English. English Studies 65: 519-533.

Emonds. Joseph. 1969. Root and structure-preserving transfonnations. Bloomington, IN: Indiana

University Linguistics Club.

Emonds, Joseph, 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax. New York: Academic

Press.

Goldberg, J., 1980. Discourse particles: An analysis of the role of J"know, I mean, well. and

actual(v in conversation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Haiman, John. ed., 1985. lconicity in syntax. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Halliday, Michael A.K., 1985. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Heine. Bernd and Elizabeth Traugott, in press. Grammaticalization. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hooper, Joan Bybee, 1975. On assertive predicates. Syntax and semantics. Vol. 4. New York:

Academic Press.

Hooper, Joan Bybee, and Sandra A. Thompson, 1973. On the applicability of root transformations. Linguistic Inquiry 4(4): 465-497.

Hopper, Paul, 1987. Emergent grammar. Papers of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley

Linguistics Society, Vol. 13, 139-157.

Hopper, Paul, 1988. Emergent grammar and the a priori grammar postulate. In: D. Tannen, ed.,

I ~88, pp. l03-120.

McDavid. Virginia, 1964. The alternation of 'that' and zero in noun clauses. Ameri;an Speei:h

:.S9: 102-113.

Mulac, Anthony, Lisa B. Studley, John, M. Wiemann and James J. Bradac, 1987. Male/female

gaze in same-sex and mixed-sex dyads: Gender-linked differences and mutual influence. Human

Communication Research 13(3): 323-343.

Ostman, J.-0., 1981. You know: A discourse-functional approach. (Pragmatics and beyond II: 7.)

Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schiffrin. Deborah. 1987. Discourse markers. Can1bridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schourup, Lawrence C., 1985. Common discourse particles in English conversation. New York:

Garland.

Tannen, Deborah, ed., 1988. Linguistics in context. New York: Ablex.

Thompson, Sandra A. and Anthony Mulac, in press. A quantitative perspective on the grammaticization of epistemic parentheticals in English. In: B. Heine and E. Traugott, eds., in press.

Underhill, Robert, 1988. The discourse conditions for that-deletion. Ms., San Diego State

University.

Urmson, J.O . 1963. Parenthetical verbs. In: C.E. Caton, ed., 1963, pp. 220-240.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Model Ship To Ship Transfer Operations PlanDocument47 pagesModel Ship To Ship Transfer Operations PlanAnkit VyasNo ratings yet

- 6 Shooting Tips From Bryan LitzDocument4 pages6 Shooting Tips From Bryan LitzMario Diez100% (1)

- Modeling SO2 absorption into NaHCO3 solutionsDocument12 pagesModeling SO2 absorption into NaHCO3 solutionsAnumFarooqNo ratings yet

- Sts OperationDocument39 pagesSts Operationtxjiang100% (3)

- Amanita Newsletter eDocument8 pagesAmanita Newsletter eidrisb59No ratings yet

- FOUNDATIONS OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS (NONLINEAR DYNAMICS, STATISTICAL PHYSICS, INFORMATION AND PREDICTION) (NICOLIS, Gregoire. NICOLIS, Catherine.) PDFDocument343 pagesFOUNDATIONS OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS (NONLINEAR DYNAMICS, STATISTICAL PHYSICS, INFORMATION AND PREDICTION) (NICOLIS, Gregoire. NICOLIS, Catherine.) PDFItalo Fabian Oliveira AraújoNo ratings yet

- Wather Fax EuropaDocument3 pagesWather Fax EuropaLemos FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Air Traffic with Statistical and Econometric MethodsDocument5 pagesForecasting Air Traffic with Statistical and Econometric MethodsLizeth DeDiaz0% (1)

- Statistical Forecasting ModelsDocument37 pagesStatistical Forecasting ModelsBalajiNo ratings yet

- HEC-HMS Release Notes 4.3Document25 pagesHEC-HMS Release Notes 4.3Agustín FerrerNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Weatherearthquakes-RamanDocument88 pagesForecasting Weatherearthquakes-RamanankitvermaNo ratings yet

- McTaggart & de Kat - SNAME 2000 - Capsize RiskDocument24 pagesMcTaggart & de Kat - SNAME 2000 - Capsize RiskEmre ÖztürkNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Agricultural GDP using Regression, ARIMA and VAR ModelsDocument19 pagesForecasting Agricultural GDP using Regression, ARIMA and VAR ModelsmanishjindalNo ratings yet

- 2020 Math Kangaroo Practice ProblemsDocument5 pages2020 Math Kangaroo Practice ProblemsadamNo ratings yet

- 2 - Rainfall Analysis2 - Rainfall Analysis With Excel - Doc With ExcelDocument6 pages2 - Rainfall Analysis2 - Rainfall Analysis With Excel - Doc With ExcelAbu Zafor100% (1)

- Second Quarter: Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionDocument11 pagesSecond Quarter: Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionJohn Benedict AlbayNo ratings yet

- IBES Reported Actual EPS and Analysts' Inferred Actual EPSDocument55 pagesIBES Reported Actual EPS and Analysts' Inferred Actual EPSamanda_p_4No ratings yet

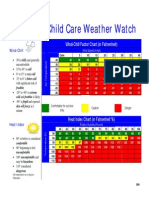

- Child Care Weather WatchDocument2 pagesChild Care Weather Watchapi-268919454No ratings yet

- Water Content in Sour GasDocument4 pagesWater Content in Sour GasAnonymous jqevOeP7No ratings yet

- Operation Management Chapter 4Document50 pagesOperation Management Chapter 4Ravivarman YalumalaiNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Seismology, Earthquakes, and Earth StructureDocument2 pagesAn Introduction To Seismology, Earthquakes, and Earth StructureMuhammadFahmiNo ratings yet

- Contenido Doc 9184 OACI Manual Planificación de Aeropuertos Parte 1 (Inglés)Document3 pagesContenido Doc 9184 OACI Manual Planificación de Aeropuertos Parte 1 (Inglés)farides garayNo ratings yet

- Mapleleaf CaseDocument15 pagesMapleleaf CaseSrv Roy80% (5)

- HE 3 Helicopter Off Airfield Landing Sites OperationsDocument24 pagesHE 3 Helicopter Off Airfield Landing Sites OperationsPablo SánchezNo ratings yet

- Casio Manual, Operation Guide 2894Document0 pagesCasio Manual, Operation Guide 2894cboutsNo ratings yet

- Ans. C: CPL MeteorologyDocument4 pagesAns. C: CPL MeteorologySandeep SridharNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science IIIDocument4 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Science IIIApril Ann Lopez Custodio94% (17)

- How Māui Brought Fire To The WorldDocument6 pagesHow Māui Brought Fire To The WorldPearl MirandaNo ratings yet

- Aman Kaura Gurinder Singh Role of Simulation in Weather ForecastingDocument4 pagesAman Kaura Gurinder Singh Role of Simulation in Weather ForecastingHarmon CentinoNo ratings yet

- Hydrometeorological Phenomenon and HazardsDocument31 pagesHydrometeorological Phenomenon and HazardsMayvin PilarNo ratings yet