Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J. Nutr.-1999-Frongillo-529

Uploaded by

Lily NGCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J. Nutr.-1999-Frongillo-529

Uploaded by

Lily NGCopyright:

Available Formats

Symposium: Causes and Etiology of Stunting

Introduction1

Edward A. Frongillo, Jr.

Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 6301

micronutrients and toxic factors); 2) infection (injury to gastrointestinal mucosa, systemic effects and immunostimulation); and 3) mother-infant interaction (maternal nutrition

and stores at birth, and behavioral interactions). The workshop group suggested that a priority for further research should

be intervention studies that enable the differentiation among

possible causal factors. The 1998 Experimental Biology symposium was timely because a number of important intervention studies have examined multiple causes of stunting during

the five years that have passed since the 1993 workshop. The

symposium was also timely because of some relatively recent

observations that affect how we think about the causes and

etiology of stunting.

Much of our thinking about why and how stunting occurs

is depicted in the classic model of the nutrition and infection

cycle (Tompkins and Watson 1989). As an explanation for

how malnutrition and disease result in excess mortality of

children, this so-called vicious cycle model has been supplanted by the synergism model (Scrimshaw et al. 1968) that

has now been demonstrated epidemiologically (Pelletier et al.

1993 and 1995). Furthermore, it is not clear how much the

nutrition and infection cycle helps us understand why and how

stunting occurs.

At the individual level, an episodic model has been demonstrated to explain daily patterns of linear growth (Lampl et

al. 1992). Growth observed daily shows periods of stasis (i.e.,

no growth) punctuated by daily saltations of growth. This

research suggests that stunting must result from a decreased

frequency of growth events, a decreased amplitude of growth

when an event occurs, or both. We do not know why and how

these might happen and which is more important.

The postnatal time most susceptible to poor linear growth

is after 3 6 mo and up to 24 36 mo (SCN 1997). Why poor

conditions have less effect after this time is not understood. A

common explanation is that poor conditions affect growth

when velocity is greater, but this is not very satisfying, especially in light of Lampl9s observations about episodic growth.

Stunting is a cumulative process that can begin in utero and

continue to ;3 y after birth. Low birth weight is an important

indicator of fetal/intrauterine nutrition and a strong predictor

of subsequent growth and well-being. Recent data from de

Onis et al. (1997) have shown that, in the least developed

countries, ;23% of infants are born with low birth weight

compared with ;7% in developed countries. The primary

reason for these high rates of low birth weight is intrauterine

growth retardation. We do not know how much prenatal

stunting contributes to the postnatal stunting we observe, and

therefore how much attention relative to causes of stunting

should be focused prenatally. Furthermore, because maternal

Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on March 15, 2016

This symposium considered why and how stunting of children occurs. As described in the comprehensive examination

made by WHO of the use and interpretation of anthropometry

(1995), stunting (i.e., short stature due to poor living environments) is one of the two most important indices of child

well-being in use throughout the world. The assessment of

stunting is integral to public health, clinical and research

workers in many fields concerned with the well-being of children and with the biology of growth and development.

In developing countries, ;40% of children ,5 y of age are

stunted [de Onis and Blossner 1997, WHO Subcommittee on

Nutrition (SCN) 1997]. This means that .200 million young

children are stunted. The timing of stunting is reasonably

understood in that most stunting occurs before the age of 3 y,

and stunted children usually become stunted adults. The consequences of becoming and remaining stunted are increased

risk of morbidity, mortality, delays in motor and mental development, and decreased work capacity (SCN 1997, Waterlow and Schurch 1994).

The causes and etiology of stunting are much less understood than are its timing and consequences. In particular,

there is little understanding of why and how stunting occurs

extensively in environments that are poor, but not desperately

so, and in environments that seem to be improving. In a

population, an individual child can become stunted or not. In

addition, some populations are much more stunted than others

(WHO 1995). This means that an understanding of why and

how children become stunted is needed at both the individual

and ecological levels.

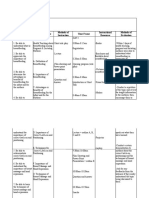

The objectives of this symposium were as follows: 1) review

and synthesize our understanding about why and how young

children become stunted, emphasizing new knowledge gained

since 1993; 2) consider the implications of this understanding

for efforts to improve child well-being; and 3) highlight new

ideas about the causes and etiology of stunting that especially

warrant further investigation in the next few years.

An important foundation for this symposium was a workshop held in London in January 1993 to examine what was

then known about the causes and mechanisms of linear growth

retardation (Waterlow and Schurch 1994). From that workshop emerged the view that the causes and etiology of stunting

include the following: 1) nutrition (energy, macronutrients,

1

Presented at the symposium Causes and Etiology of Stunting as part of

Experimental Biology 98, April 18 22, 1998, San Francisco, CA. The symposium

was sponsored by the American Society for Nutritional Sciences and the Society

for International Nutrition Research. Published as a supplement to The Journal of

Nutrition. Guest editor for the symposium publication was Edward A. Frongillo,

Jr., Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

0022-3166/99 $3.00 1999 American Society for Nutritional Sciences. J. Nutr. 129: 529S530S, 1999.

529S

530S

SUPPLEMENT

child interactions relate to growth failure. Ramakrishnan,

Martorell, Schroeder and Flores present evidence on why and

how stunting persists across generations.

LITERATURE CITED

Cohen, R. J., Brown, K. H., Canahuati, J., Landa Rivera, L. & Dewey, K. G. (1994)

Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on infant breast milk

intake, total energy intake, and growth: a randomised intervention study in

Honduras. Lancet 344: 288 293.

de Onis, M. & Blossner, M. (1997) World Health Organization Global Database

on Child Growth and Malnutrition. WHO/NUT/97.4. Programme of Nutrition,

WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

de Onis, M., Blossner, M. & Villar, J. (1997) Levels and patterns of intrauterine

growth retardation in developing countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 52 (suppl. 1):

515.

Engle, P., Lhotska, L. & Armstrong, H. (1997a) The Care Initiative: Assessment,

Analysis and Action to Improve Care for Nutrition. United Nations Children9s

Fund, Nutrition Section, New York.

Engle, P., Menon, P. & Haddad, L. (1997b) Care and Nutrition: Concepts and

Measurement. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

Farnum, C. & Wilsman, N. J. (1998) Growth plate cellular function. In: Skeletal

Growth and Development: Clinical Issues and Basic Science Advances

(Buckwalter, J., Ehrlich, M., Sandell, L. & Trippel, S., eds.), pp. 203223.

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Frongillo, E. A., Jr. (1996) The Effects of Timing and Type of Complementary

Foods on Post-Natal Growth. Report submitted to the Nutrition Unit, Division

of Food and Nutrition, World Health Organization. Division of Nutritional

Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Frongillo, E. A., Jr, de Onis, M. & Hanson, K.M.P. (1997) Socioeconomic and

demographic factors are associated with worldwide patterns of stunting and

wasting. J Nutr. 127: 23022309.

Gillespie, S., Mason, J. & Martorell, R. (1996) How Nutrition Improves. ACC/

SCN State-of-the-Art Series, Nutrition Policy Discussion Paper # 15. United

Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committe on Nutrition, Geneva, Switzerland.

Jonsson, U. (1995) Towards an improved strategy for nutrition surveillance.

Food Nutr. Bull. 16: 102111.

Lampl, M., Veldhuis, J. D. & Johnson, M. L. (1992) Saltation and statis: a model

of human growth. Science (Washington, DC) 258: 801 803.

Pelletier, D. L., Frongillo, E. A., Jr. & Habicht, J. P. (1993) Epidemiologic

evidence for a potentiating effect of malnutrition on child mortality. Am. J.

Public Health 83: 1130 1133.

Pelletier, D. L., Frongillo, E. A. Jr., Schroeder, D. G. & Habicht, J. P. (1995) The

effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull. WHO

73: 443 448.

Scrimshaw, N. S., Taylor, C. E. & Gordon, J. E. (1968) Interaction of Nutrition

and Infection. Monograph series 57. World Health Organization, Geneva,

Switzerland.

SCN (1997) Stunting and young child development. In: Third Report on the

World Nutrition Situation. United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committe on Nutrition, Geneva, Switzerland.

Tomkins, A. & Watson, F. (1989) Malnutrition and Infection: A Review. United

Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committe on Nutrition, Geneva, Switzerland.

Waterlow, J. C. & Schurch, B. (1994) Causes and Mechanisms of Linear

Growth Retardation. Proceedings of an I/D/E/C/G Workshop held in London,

January 1518. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 48: S1S216.

Wilsman, N. J., Farnum, C. E., Leiferman, E. M. & Lampl, M. (1998) Consideration of growth plate biology in the context of growth by saltations and

stasis. In: Saltation Stasis and Human Growth (Lampl, M., ed.). Smith-Gordon, London (in press).

World Health Organization (1995) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation

of Anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Technical Report

Series no. 854. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

World Health Organization Working Group on Infant Growth (1994) An Evaluation of Infant Growth. Doc WHO/NUT/94.8. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

World Health Organization Working Group on Infant Growth (1995) An evaluation of infant growth: the use and interpretation of anthropometry in infants.

WHO Bull 73: 165174.

Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on March 15, 2016

size, nutrition, and other factors are important determinants of

prenatal size, why and how stunting occurs is potentially

explainable at least in part by conditions that affected the

previous generation.

Recently, there has been substantial attention paid to the

role of feeding mode on growth patterns of infants. For example, the WHO Working Group on Infant Growth (1994 and

1995) has shown that the pattern of growth for breast-fed and

formula-fed infants differs substantially. Subsequent research

has shown that the pattern of growth is not sensitive to the

duration of breast-feeding (Cohen et al. 1994, Frongillo 1996).

Why these patterns are different and what this might tell us

about why and how stunting occurs is not understood.

It has long been recognized that deficits in macronutrients

cause stunting, but there has been increasing attention paid to

the role of micronutrients. We must determine for which

micronutrients do deficits limit growth and whether stunting is

due primarily to deficits in single nutrients or in multiple

nutrients simultaneously.

The United Nations Children9s Fund, through its wellknown conceptual model and more recent Care Initiative

(Engle et al. 1997a) has helped bring to our attention the role

of maternal and child care in child nutrition. Understanding

the ways in which care affects why and how stunting occurs is

limited (Engle et al. 1997b).

The UNs Coordinating Subcommittee on Nutrition has

just published its Third Report on the World Nutrition Situation. The prevalence of stunting and recent rates of progress

differ substantially across regions (SCN 1997). We can explain

about three quarters of the variability among countries in the

prevalence of stunting by social, human development and

economic factors (Frongillo et al. 1997). But we know less

about why and how some countries improve and others do not

(Gillespie et al. 1996).

WHO has proposed that the goal for reducing stunting

should be that the prevalence of stunting in any country

should be ,20% by the year 2020. Only about one quarter of

developing countries meet that target now, and if past trends

continue, only about one half would meet that target in the

year 2020 (SCN 1997). It is important to identify what are the

most important actions to be taken to make better progress,

and what research be done to assist with these decisions.

The papers presented in this symposium aimed to address

many of these issues. Answering why and how stunting occurs

requires fundamental understanding of how bones elongate to

produce linear growth. This understanding has been lacking,

but Wilsman, the first presenter at the symposium, provides

some clues concerning the nature of this process (see: Farnum

and Wilsman 1998, Wilsman et al. 1998). The paper by

Rosado for this symposium presents evidence that stunting is

associated with marginal deficiencies of several micronutrients

simultaneously. Stephensen discusses current thinking about

how infection may play a causal role in stunting. Black and

Krishnakumar examine how factors such as child temperament, maternal depression, and responsiveness of maternal-

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Nursing Care of The High Risk NewbornDocument8 pagesNursing Care of The High Risk NewbornFebie GonzagaNo ratings yet

- BemoncDocument84 pagesBemoncJUANJOSEFOX100% (1)

- Improve Nursing Skills and Knowledge with Medical Case Studies and QuestionsDocument41 pagesImprove Nursing Skills and Knowledge with Medical Case Studies and Questionsjodymahmoud100% (1)

- Common Diseases of NewbornDocument162 pagesCommon Diseases of NewbornMichelle ThereseNo ratings yet

- EKB Growth Trajectory and Assessment Influencing Factors and Impact of Early NutritionDocument226 pagesEKB Growth Trajectory and Assessment Influencing Factors and Impact of Early NutritionBoris Guillermo Romero RuizNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Emergencies FinalDocument90 pagesNeonatal Emergencies FinalDr Raseena VattamkandathilNo ratings yet

- Maternity Newborn and Womens Health Nursing A Case Based Approach First Edition Ebook PDFDocument62 pagesMaternity Newborn and Womens Health Nursing A Case Based Approach First Edition Ebook PDFbenjamin.waterman189100% (48)

- Nle Pre Board June 2008 Npt2-Questions and RationaleDocument22 pagesNle Pre Board June 2008 Npt2-Questions and RationaleJacey Racho100% (1)

- 0 4stunting WHODocument3 pages0 4stunting WHOLily NGNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DeterminanDocument8 pagesJurnal DeterminanLily NGNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Publikasi Iriyanti Aderina Patola 2015 PDFDocument10 pagesJurnal Publikasi Iriyanti Aderina Patola 2015 PDFLily NGNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2000 Perks 1455 60Document6 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2000 Perks 1455 60Lily NGNo ratings yet

- Patient Ed 5e 153Document1 pagePatient Ed 5e 153Lily NGNo ratings yet

- J. Nutr.-1999-Frongillo-529Document2 pagesJ. Nutr.-1999-Frongillo-529Lily NGNo ratings yet

- Files 10624pfibrosarcomaDocument4 pagesFiles 10624pfibrosarcomaLily NGNo ratings yet

- CHANG Et Al-2010-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyDocument6 pagesCHANG Et Al-2010-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyLily NGNo ratings yet

- WHO classification of soft tissue tumours guideDocument10 pagesWHO classification of soft tissue tumours guidezakibonnie100% (1)

- 0 4stunting WHODocument3 pages0 4stunting WHOLily NGNo ratings yet

- StuntingDocument10 pagesStuntingFrancisca Anggun WNo ratings yet

- NCBIDocument3 pagesNCBILily NGNo ratings yet

- Hunt JurnalDocument29 pagesHunt JurnalLily NGNo ratings yet

- Coffey Deaton Dreze Tarozzi Stunting Among Children EPW 2013Document3 pagesCoffey Deaton Dreze Tarozzi Stunting Among Children EPW 2013Lily NGNo ratings yet

- 0 4stunting WHODocument3 pages0 4stunting WHOLily NGNo ratings yet

- CHANG Et Al-2010-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyDocument6 pagesCHANG Et Al-2010-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyLily NGNo ratings yet

- 44 86 1 SMDocument5 pages44 86 1 SMLily NGNo ratings yet

- BPPVDocument12 pagesBPPVBenny BoisalaNo ratings yet

- Vertigo03 10Document3 pagesVertigo03 10CalvinNo ratings yet

- Engaruhobatkumurkhlorheksidin2000Document9 pagesEngaruhobatkumurkhlorheksidin2000Dyah Wulan RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- 6130 17633 1 PBDocument8 pages6130 17633 1 PBLily NGNo ratings yet

- BPPVDocument6 pagesBPPVLily NGNo ratings yet

- Post Date8Document13 pagesPost Date8Afrilya Christy SitepuNo ratings yet

- 3922 5465 1 SMDocument9 pages3922 5465 1 SMLily NGNo ratings yet

- 275 FullDocument6 pages275 FullLily NGNo ratings yet

- Ergot 2Document4 pagesErgot 2Lily NGNo ratings yet

- Alterna RiaDocument5 pagesAlterna RiaLily NGNo ratings yet

- Mycotoxins WHODocument42 pagesMycotoxins WHOLily NGNo ratings yet

- Efek Mycotoxin WHODocument13 pagesEfek Mycotoxin WHOLily NGNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry Kampala International University Western Campus UgandaDocument11 pagesFaculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry Kampala International University Western Campus UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Woobaidal 2016Document19 pagesWoobaidal 2016Visa LaserNo ratings yet

- Pressure Points - Postnatal Care Planning PDFDocument15 pagesPressure Points - Postnatal Care Planning PDFNoraNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Discharge InstructionsDocument7 pagesPostpartum Discharge InstructionsGilianne JimeneaNo ratings yet

- Is Formula Good for BabiesDocument4 pagesIs Formula Good for BabiesInda KecilNo ratings yet

- BreastfeedingDocument111 pagesBreastfeedingabdur rahman zulkifliNo ratings yet

- Care of Low Birth Weight (LBW) BabiesDocument44 pagesCare of Low Birth Weight (LBW) BabiesSubhajit Ghosh100% (1)

- BSES OriginalDocument12 pagesBSES OriginalIntan DwiNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Policy BriefDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Policy BriefPuput Dwi PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical and Health Care AssociationDocument47 pagesPharmaceutical and Health Care AssociationKenneth FabiaNo ratings yet

- ExamDocument67 pagesExamJOHN CARLO APATANNo ratings yet

- Instructional Design Project Identification Template 281 29Document2 pagesInstructional Design Project Identification Template 281 29api-627764163No ratings yet

- Impact On Delayed Newborn Bathing On Exclusive Breastfeed - 2019 - Journal of NeDocument6 pagesImpact On Delayed Newborn Bathing On Exclusive Breastfeed - 2019 - Journal of NeCarol HNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Pemberian Booklet Asi Eksklusif Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Keterampilan IbuDocument7 pagesPengaruh Pemberian Booklet Asi Eksklusif Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Keterampilan IbuSepta KatmawantiNo ratings yet

- Approved MICS Balochistan Final Report 23 November 2011 PDFDocument318 pagesApproved MICS Balochistan Final Report 23 November 2011 PDFAkhtar RashidNo ratings yet

- 2017avril Cantoni RlunchDocument33 pages2017avril Cantoni RlunchJIAMING TANNo ratings yet

- QuestionareDocument22 pagesQuestionareash aliNo ratings yet

- Bsc. Nursing Examination: Revision QuestionsDocument79 pagesBsc. Nursing Examination: Revision QuestionsNixi MbuthiaNo ratings yet

- Learning Objectives Content Outline Methods of Instruction Time Frame Instructional Resources Methods of EvaluationDocument3 pagesLearning Objectives Content Outline Methods of Instruction Time Frame Instructional Resources Methods of EvaluationteuuuuNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument78 pagesCase StudyRAGHVENDRANo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Medication Use in Pregnancy and BreastfeedingDocument19 pagesPsychiatric Medication Use in Pregnancy and BreastfeedingYamiletRomeroVillaNo ratings yet

- 4 5920472882638490310 Removed RemovedDocument97 pages4 5920472882638490310 Removed Removedsameena vNo ratings yet