Professional Documents

Culture Documents

048 - 2002 - V2 - Jose Aguirre - Beyond The Dictionary in Spanish

Uploaded by

escarlata o'haraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

048 - 2002 - V2 - Jose Aguirre - Beyond The Dictionary in Spanish

Uploaded by

escarlata o'haraCopyright:

Available Formats

THE DICTIONARY-MAKING PROCESS

Beyond the Dictionary in Spanish

Jos Aguirre

CardiffUniversity

Hispanic Studies, EUROS

CardiffUniversity

P.O.Box 908

CF13YQCardiff

United Kingdom

Abstract

This paper argues that there is a gap between language as recorded by the traditional standard Spanish

dictionaries and the way language is actually used by the media, and considers the recent success of Spanishlanguage style manuals as proof of the need to deal with the inadequacies of traditional lexicography.

Distinctions are drawn between style manuals and dictionaries of correct usage. Comparisons are made

between different style manuals in order to establish the underlying nature of the (grammatical and lexical)

items covered, and the treatment of these categories of items in style manuals is compared to the one given by

traditional monolingual (and one bilingual) standard dictionaries.This paper then tries to identify those areas

where the traditional dictionary is at fault: updating, breadth and depth of (lexical and grammatical) coverage

and contrastive treatment ofitems. Finally, it is argued that style manuals point the way the standard dictionary

should go in order to be a successful linguistic tool.

The title ofthis paper is that ofa book published in 1953 by Gerrard and Heras. This brief

glossary showing peculiarities of meaning and usage in Spanish for the English-speaking

learner, although confined to colloquial speech and now somewhat outdated, still remains of

interest because it shows an early realization ofthe gap between the dictionary and its users.

Half a century later, the gap still exists, not just affecting the foreigner trying to cope with

colloquial speech, but rather the Spanish native speaker when confronted with the standard

language as used by the media. Is will try to show how the needs of the user faced with the

inadequacies ofthe dictionary are fostering a new breed oflinguistic products, which in turn

points to the new direction that the traditional standard dictionary should attempt to follow in

order to be a successful linguistic tool.

Since the early 1990s, Spain has undergone a startling process oflanguage awareness: the

Spanish language has become a popular issue and the market has both responded and

fostered that awareness by the publication of a number of landmark monolingual and

bilingual dictionaries: the 8-volume DCR initiated by Cuervo in 1886 was finally completed

in 1995 [Cuervo 1998]; the long-awaited DEA [Seco et al. 1999] saw the light after 30 years

in the making. There have been also new editions ofthe DRAE [RAE 1992; 2001] and DUE

[Moliner 1998]. In the field of bilingual lexicography, beteween 1988 and 2000 Collins

published five editions oftheir classical English-Spanish dictionary [Smith et al. 2000], and

Oxford U.P. published the Oxford Spanish Dictionary in 1994, with a second edition in 1998

and a revision [Galimberti et al. 2001]. In addition, a vast array ofgood dictionaries ofall

441

ERALEX 2002 PROCEEDINGS

sorts and sizes has been published over the last 10 years, together with bestselling books on

language usage, such as that by Lzaro [1997], a compilation of his newspaper articles

published between 1975 and 1996, which sold 250.00 copies in one year and is but one

example of his influential role in the development of the media style manuals through his

prefaces to several ofthem (e.g. [ABC 1993; Mendieta 1993]) and his collaboration with

Agencia EFE. But the most striking feature ofthis trend has been the successful publication

of over 30 different "libros (or manuales) de estilo" (style manuals)1 and of several

"diccionarios de dudas" (dictionaries of correct usage). I am not concerned here with the

latter, but a distinction should be made between these two closely related types ofwork.

The Spanish "diccionario de dudas" is best exemplified by Seco's classical DDDLE [1998]

(10 editions between 1961 and 1998) which has achieved great following both in Spain (e.g.,

^iartinez de Sousa 1998]) and in Latin-America (e.g., [Arag 1995]). His work discusses

alphabetically lexical, syntactical and other contentious issues covering the whole range of

contemporary language, which are documented by quotations from written (and some oral)

sources.

The style manuals differ from the dictionaries of correct usage on several accounts. First,

although some ofthem have been published by political institutions (e.g., [MAP 1991;

Diputacin Sevilla 1999]), universities (e.g., [UNED 1994]), publishing houses (e.g.,

pviuchnik 2000]) or other bodies, most have been typically issued by a media organization,

mostly newspapers (cfr. [ABC 1993; El Mundo 1996; El Pais 1999; La Vanguardia 1986],

etc.), but also news agencies (such as those by [EFE 1992, 1995, 2000]) and television

stations (e.g., pviendieta 1993; Telemadrid 1993; Canal Sur 1991]). It should be noted that I

am not referring to in-house style guides which most ofthe media (ifnot all) are assumed to

have and implement. This was the case, for instance, with early editions ofthe El Pais ' style

manual which were never really available to the public until the third one was issued in

1990, and the same could be said ofother style manuals, issued first internally and made

commercially available at a later date.

The second difference stems from this commercial availability of the style manual and

concerns the degree of its influence. The dictionary of correct usage may favour one way or

another of using language, but by being addressed to the general public only, its impact is

indirect and theoretical ('4his is what we would say"). On the other hand, the norms laid

down in the style manual, by being both commercially available to the general public and

also typically binding on all staff working for that media, exert an influence on the public

which is direct and indirect, theoretical and at the same time practical ("not only do we

favour this norm, but we also implement it in our use ofthe language"). The actual influence

ofthe media on the way language is used is something that cannot possibly be measured, but

some data can be ofhelp. In 1997 the two channels belonging to Spanish state television

(TVE1 and TVE2) achieved a combined 34% ofthe audience (see [El Pais 1998]). As for the

press, Diaz [1999a, p.l20; 1999b, p. 186] shows that in 1997 the circulation ofthe four

leading Spanish daily newspapers (El Pais, ABC, El Mundo, La Vanguardia) accounted for

almost 30% ofthe total, while injune 1998 El Pais internet site was the second most visited

website in Spain, with that ofEl Mundo ranked 9th, ABC's 14th, and La Vanguardia's 19th.

Finally, EFE is the world's largest Spanish-language news agency and the fourth largest

442

THE DICTIONARY-MAKING PROCESS

news agency overall. If we add to this the fact that all these media organizations have each

issued at least one style manual (3 different ones in the case of EFE), which have run to

several editions (15 in the case oiEl Pais, 11 ofEFE's Manual de espaol urgente), then we

can begin to realize the scale ofthe phenomenon we are dealing with.

The third difference relates to the contents. The dictionary ofcorrect usage attempts to cover

the whole range of contemporary language -including literary language- (with an emphasis

on the grammatical irregularities, spelling, etc), whereas the style manual is concerned

solely with those areas related to the language of news coverage in its broadest sense,

leaving aside questions of literary register or historical interest, with limited emphasis on

purely grammatical or spelling matters, but focusing rather on contentious lexical items of

immediate interest because oftheir appearance in everyday news.

Comparison of different style manuals is rendered difficult by their disparity in size,

structure, date ofpublication, and also by the varying nature ofthe issuing organization and

their intended users , but some telling remarks can be made. Firstly, there is hardly any

unanimity about how many and which items to include; [El Pais 1999] contains 324 entries

beginning with 'a', while pEl Mundo 1996] records (albeit in 3 different sections) a similar

number, 346. However, they only share 172 entries, so that about half of each manual's

entries are not contained in the other one. Similarly, [ABC 1993] contains 107 entries

beginning with 'a', against 83 in [Mendieta 1993], with only about one third ofthem (31)

appearing in both, perhaps reflecting their different sources: the DDDLE ([Seco 1998]) for

[ABC 1993] and [EFE 1995] for [Mendieta 1993].

However, there is certainly some common ground in the nature ofthe items included, which

will be useful to identify those areas where the traditional standard dictionary fails its user. I

will make reference to the best three monolingual Spanish dictionaries: DRAE-22 ([RAE

2001]), DUE ([Moliner 1998]) and DEA ([Seco et al. 1999]) and to Collins-6 bilingual

dictionary ([Smith et al. 2000]).

Two distinct groups of items can be identified in the style manual. On the one hand, the

following grammatical items are included in most ofthem: '

-use of prepositions and prepositional phrases, one of the most changing areas of language

(cfr. [Garcia Yebra 1988]); e.g., most ofthe style manuals condemn the use of"a bordo de"

when referring to a car or vehicle, a use which is recorded only -though not condemned- by

DEA.

-verbal patterns: "incautarse de algo" against the 'incorrect' but common transitive use

"incautar algo", a pattern condemned by all style manuals but only recorded by Collins-6

among our four dictionaries; or the use of the prefix "auto-" with verbs which are already

reflexive: "autoproclamarse", "autodefinirse" -not in DUE or DRAE-22, but recorded in

DEAsnaCollins-6-.

-use or omission ofthe articlewith place names and years ("Lbano" or "el Lbano", "en

2001" or "en el 2001"), differences between direct and reported speech, and use ofobject

443

ERALEX 2002 PROCEEDINGS

pronouns are areas not covered by the traditional dictionary.

-general irregularities ofthe language (defective verbs, cases where peculiar agreement takes

place, doubtful plurals) which, in general, are adequately treated by the traditional dictionary

on an individual basis.

-certain uses of verbal tenses and forms (use of the three past tenses; the so-called

"condicional de rumor", when the conditional tense is used to convey the idea that reports or

news are unconfirmed; "haber" as impersonal verb and therefore in no need of agreement in

number with the following direct object). These matters are generally omitted from the

traditional dictionary.

-spelling, stress marks, punctuation, use of hyphens (which affects stress, spelling, plural

forms and derivatives), use of italics, capitalization of certain words. Only the first two

issues are satisfactorily dealt with in the traditional dictionary, and again only on an

individual basis.

As we can see, the standard traditional dictionaries (including, to some extent, the bilingual

ones) do not always address these points satisfactorily, partly due to a deep-seated reluctance

to integrate the treatment of grammatical issues in the dictionary4, and partly because the

traditional dictionary seems unable to go beyond the individual treatment and arrangement

ofitems and cannot therefore provide the contrastive approach favoured by the style manual.

Apart from grammatical matters, style manuals tend to focus on the following types of

lexical items:

-foreign names that pose translation, spelling, transcription or transliteration problems: Pedro

el Ermitafio / Peter the Hermit; Walter de la Mare, Robert De Niro, Eamon de Valera

(example taken from [Austin 1999]); Ten Hsiao-Ping / Den Xiaoping; Yeltsin / Eltsin /

Ieltsin. Only Collins-6 offers some help with translated (historical) names and familiar forms

(Pepe).

-"exonimos" (place names that have different forms in different languages): Aquisgrn /

Aachen / Aix-la-Chapelle. Again, these raise questions about spelling, transliteration and

transcription. Translation problems are also involved (compare "Middle East" in [Austin

1999] or [Jenkins 1992] with "Oriente Medio" in [EFE 2000]). The bilingual dictionary is

the only one to provide some guidance in this matter.

-adjectives denoting nationality or origin, particularly those that have appeared frequently in

the news in recent years, such as "abjasio", "bangladesi" or "oseta", none of which are

recorded in DUE or DRAE-22; the first two in Collins-6; all three only in DEA. In such

cases, problems arise concerning spelling, transliteration or transcription, meaning and

translation.

-confusible meanings ("infligir" vs. "infringir") are recorded in most dictionaries on an

individual basis, but no attempt is made to differentiate between them.

444

THE DlCnONARV-MAKNG PROCESS

-contentious uses ofwords, such as the much used and condemned "ostentar (un cargo)" (to

hold office), only recorded -but not condemned- by DEA and Collins-6.

-acronyms. It should be noted that in many respects acronyms in Spanish behave like nouns:

some have plural forms ("S.M.", su majestad; "SS.MM.", sus majestades), many are used

with the article agreeing in gender with the main word ("la OTAN"), all ofthem have a full

form ("UNHCR" is "ACNUR" in Spanish, but the C is variously understood as "Comisara",

"Comisionado" and "Comisariado", the last two forms triggering the use of the masculine

article). In many cases, meaning and translation problems arise. Many give rise to

derivatives: DEA records "otanico", "otanismo" and "otanista", but not "OTAN". Some

acronyms are 'read' by spelling them ("ATS"), others as if they were words ("UNED"),

while some are unpredictably read as a mixture of both ("CSIC"). Nevertheless, all standard

Spanish dictionaries omit acronyms, and only Collins-6 records a number ofthem.

-false friends, whether syntactical (such as overuse of passive sentences) or lexical, due to

mistranslation of (mainly) English words of similar form: e.g., "domstico" (in the sense of

"domestic flight", not recorded in DUE or DRAE-22, but included in DEA and Collins-6)

-loanwords from any other language enter the standard dictionary only after a considerable

period oftime, ifat all. The word "taliban" appeared in the Spanish press at about the same

time as in English, early in 1995. Seven years later, it is only recorded in two ofour four

standard dictionaries. DUE includes the etymology but the definition names Pakistan and

fails to mention Afghanistan. DRAE-22 omits the etymology and gives a poor definition.

None of them mention any other issues. It is true that in Spanish there is no doubt as to its

transliteration and that forms such as "Taleb" or "Taleban" (the only ones recommended by

[Austin 1999] and used by some English-language newspapers) are hardly used; '4aliban" is

always written with an acute accent and hardly ever is it capitalized the way it is sometimes

in English. But the important question remains ofwhether to use '4alib" (sing.) and "taIiban"

(pl.) or else "taliban" (sing.) and "talibanes" (pl.)5'6. Many other loanwords (even from

languages such as Basque, Catalan and Galician) are still unrecorded, and style manuals are

the only works to provide some guidance.

-neologisms. New senses of existing words, including new collocations (such as "tarifa

plana") are quite often not recorded by standard dictionaries; and the same problem arises

with new words ("apalizar" only appears in DEA and Collins-6; "judicializar" and

"judicializacion" only in DEA; none ofour four dictionaries record "prepartido").

-Latin phrases, which raise questions of form, meaning and use, are more often than not

omitted from the dictionary. E.g., only DEA mentions that "grosso modo" is frequently used

with the preposition "a": "a grosso modo", although this use is mentioned -and condemnedby most style manuals.

Bailey [1989] identified the two main shortcomings in English dictionaries as: a) failure to

cover the breadth of the vocabulary, and b) lack of depth of coverage. This would, in my

opinion, constitute a fair description ofthe state ofSpanish monolingual lexicography, but I

445

ERALEX 2002 PROCEEDINGS

would like to qualify these two issues in the light ofthis analysis oflexical items covered by

style manuals and their presence or absence in standard dictionaries so as to draw some

conclusions.

First, lack of breadth of coverage should not be interpreted as simply the absence of rare or

archaic lexical items from our dictionaries. There is a deep-rooted reluctance on the part of

traditional lexicographers to include whole types of lexical items in their word-list. As we

have seen, proper names, 'exonimos' and acronyms are excluded from the dictionary, but we

have to realize that these items are an integral part oftoday's language, notjust on a purely

paradigmatic level (as lexical units in their own right), but also on the syntagmatic level,

since they have a wide varietey ofgrammatical, usage and translation implications. All these

items have an unequivocal linguistic nature, and the fact that some of them might

additionally have encyclopaedic features should not be regarded as reason enough to omit

them from the dictionary (see [Lzaro 1973; Room 1986]). Failure to cover other types of

lexical items may be attributed to one or more of several factors: adjectives denoting

nationality or origin may be absent from the dictionary due to lack of updating or because

not enough attention is paid to the way the language is actually used. The same could be said

about the omission of loanwords and neologisms, but this could also be put down to a

fundamentalist approach to language that does not regard them as "proper" lexical items.

Disregard for the actual use of language could explain the omission of contentious uses,

Latin phrases and false friends, but again this could be due to the desire "to proscribe by

omission" certain uses regarded as incorrect.

With regard to Bailey's second point, lack of depth of coverage, again this must not be

understood as merely the omission of certain senses of words, but also as the omission of

certain types of information about the lexical items. We have already mentioned the

unwillingness to integrate the treatment ofgrammatical issues into the traditional dictionary,

but lack ofdepth ofcoverage affects other aspects ofthe linguistic description ofthe items.

We take for granted a consistent treatment of homographs in the dictionary, but there is less

consistency when it comes to homophones ("acerbo" and "acervo") and none should be

expected when we deal with words being misused on account of their similar pronunciation

("infligir" and "infringir") because the traditional dictionary will not contemplate a

contrastive approach. We expect a reasonable treatment of etymology in our dictionaries,

and yet we are not given information on transliteration or transcription ofmodern loanwords.

The traditional dictionary will not record the pronunciation of acronyms or the syntagmatic

patterns of lexical items, let alone cultural or usage notes (e.g., on irregular plural forms of

modern loanwords).

The appeal of the style manual in Spanish, its usefulness, and its success over the last ten

years, seem to lie in several factors in which the traditional dictionary is at fault7: updating,

breadth and depth of (lexical and grammatical) coverage and contrastive treatment of items

and problems encountered in dealing with everyday language as used by the media. It should

be noted, however, that the style manual has several shortcomings of its own: in common

with most standard monolingual and bilingual dictionaries, it seems to have no clear-cut

criteria for the placement of multiword lexical units; some are given their own entry while

others are treated under the entry for the main word, which in turn is not always correctly

446

THE DICTIONARY-MAKING PROCESS

identified. Sometimes it is clear that the style manual simplifies information obtained from

other sources where each point is dealt with in more detail: [ABC 1993] reduces the 9-line

entry for "audiencia" in EFE 1995] to a 2-line entry that is baffling. In addition, there is no

unanimity as to the solutions favoured by each style manual, which often leads to cases

where two of them defend conflicting solutions8. This is tied to the main shortcoming in

most books of this kind: the frequent absence of any kind of explanation or sufficient

reasoning as to why one solution is preferable to another. It is true that the user seeks to find

quick and easy guidance on matters of usage, but quite often prescriptive statements of the

kind '4^fot A but B" leave the reader mystified as to the reasons behind that choice; when the

language offers alternative forms of expression this is because they are different -however

small that difference may be- and the preference of one over another should be based on a

reasonedjudgement. It is quite natural, however, for the user in need ofguidance to turn to

those works which provide some answers -however incomplete- rather than to those which

ignore altogether the endless possibilities of language. However, the success of the style

manuals should not be considered the solution to our main lexicographical problems; rather,

they are a symptom of the state of monolingual Spanish lexicography, but one that

(paradoxically) points the way forward ifthe dictionary is to be a successful linguistic tool:

the dictionary should go beyond its traditional self.

Endnotes

(1): This phenomenon is not confined to Spanish, but extends also to Galician (e.g., [Arias 1993])

and Catalan (e.g., [Coromina 1995; Oliva 1997]), and Latin-America (^a Nacin 1997]).

(2) Typically, style manuals contain sections on the nature of modern, free, objective journalism,

about the professional ethics ofthe media, typographical matters, the role ofthe images, etc. but no

mention will be made ofthese unless related to language use.

(3) Interestingly, no great differences could be observed between those issued by newspapers and

those issued by television stations, except that the latter make some reference to pronunciation.

(4) A sad example ofthis fundamentalist approach in lexicography: in 1966, Maria Moliner, in a

ground-breaking decision, integrated within the word-list of the first edition of the DUE quite a

number of entries where grammatical issues were dealt with in depth. Regrettably, the editors of the

1998 edition reversed that decision and, with no soundjustification, relegated all the grammatical

entries to an appendix.

(5) The Spanish language seems curiously unable to cope with the plural form ofloanwords which do

not display a final -s. The classic example of these 'regularized' plural forms are "querubines" and

"serafines", "lands" or "landers" and "lieds". More modem examples have followed: '4argui tuareg/tuaregs", "feday - fedayin/fedayines", 'fauyahid - muyahidirvmuyahidines" and the latest very close to the case of'4alib"- the Persian "pasdar - pasdaran/pasdaranes".

(6) Derivatives have appeared in English ("...before the pax Talibamca". Guardian Weekly, 6-7-97,

2; "Talibanization" in 1998; "Talibanic" Washington Post, 6-3-2001, 23) and Spanish ("...registrando

una cierta '4alibanizacion"..." EFE News Services, 23-2-2000; "...matar talibanes (o talibanas, o

talibancitos, segn la latinizacin de la Academia)." Pais, 3-11-01, 61), raising the possibility of

feminine and diminutive forms being used ("...con las fuerzas talibanas." EFE News Services, 20-102001). It is obviously too early to record them, but it will be interesting to see their fate in future

dictionaries.

(7) It is quite obvious that each ofthe four dictionaries used responds differently. Among the three

monolingual ones, DEA is the most useful because its word-list and all senses and definitions are

strictly based on written contemporary sources, without any apparent prescriptive bias. The bilingual

dictionary, on the other hand, faced with the practical problems of the translation process, tends to

447

EURALEX 2002 PROCEEDINGS

display greater inclusiveness (both of lexical items and of types of information, even including

cultural and usage notes) and cannot afford to be prescriptive.

(8) Some examples related to matters of stress and spelling -usually not the most contentious issues

in Spanish-: pl Mundo 1996] defends "audfono", "autostop" and "reuma", while pE Pas 1999]

favours "audifono", "autoestop" and "rema". [ABC 1993] draws a distinction between "entreno"

and "entrenamiento", while PS1 Mundo 1996] states that "entreno" does not exist and the word to use

is "entrenamiento".

References

[ABC 1993] ABC, 1993. Libro de estilo de ABC. Ariel, Barcelona.

[Arag 1995] Arag, M., 1995. Diccionario de dudasyproblemas del idioma espaol. El Ateneo,

Buenos Aires.

[Arias 1993] Arias, V., 1993. Libro de estilo. Xunta de Galicia, Santiago.

[Austin 1999] Austin, T. (comp.), 1999: The Timesguide oEnglishstyle andusage. Times Books,

London.

P3ailey 1989] Bailey, R., 1989. On some discontiguities in our English dictionaries, in: R. Bailey

(ed.) Dictionaries ofEnglish: prospectsfor the record ofour language, pp. 136-161. Cambridge

U.P., Cambridge.

[Canal Sur 1991] Canal Sur, 1991. Libro de estilo. Canal Sur, Sevilla.

[Coromina 1995] Coromina, E., 1995. El nou 9: manual de redacci i estil. 4th ed. Eumo Editorial,

Vic.

[Cuervo 1998] Cuervo, R.J., 1998. Diccionario de construccinyrgimen de la lengua castellana. 8

vols. Herder, Barcelona. (DCR)

Paz 1999a] Daz Nosty, ., 1999. Las ediciones digitales de la prensa diaria en lengua espaola, in:

El espaol en el mundo: anuario delInstituto Cervantes 1999, pp. 65-129. Instituto Cervantes,

Alcal de Henares.

PDaz 1999b] Daz Nosty, B., 1999. La difusin de la prensa diaria en lengua espaola, n: El espaol

en el mundo: anuario del Instituto Cervantes 1999, pp. 131-186. Instituto Cervantes, Alcal de

Henares,

fpiputacin Sevilla 1999] Diputacin Sevilla, 1999. Manual de estilo administrativo. Diputacin

Sevilla, Sevilla.

pFE 1992] EFE, 1992. Vademcum de espaol urgente EFE, Madrid.

pFE 1995] EFE, 1995. Manual de espaol urgente. 1 lth ed. Ctedra, Madrid.

pFE 2000] EFE, 2000. Diccionario de espaol urgente. Agencia EFE - Editorial SM, Madrid.

1 Mundo 1996] El Mundo, 1996. Libro de estilo de ElMundo. Unidad Editorial, Madrid.

1 Pas 1998] El Pas, 1998. Anuario de El Pas 1998. Ed. en CD-ROM. El Pas, Madrid.

1 Pas 1999] El Pas, 1999. Libro de estilo de ElPais. 15th ed. El Pas, Madrid.

[Galimberti et al. 2001] Galimberti, B., et al., 2001. The OxfordSpanish Dictionary. 2nd ed. revised

with supplements. Oxford U.P., Oxford.

[Garcia Yebra 1988] Garcia Yebra, V., 1988. Claudicacin en el uso depreposiciones. Gredos,

Madrid.

[Gerrard & Heras 1953] Gerrard, A.B., and J. de Heras, 1953. Beyondthe dictionary in Spanish.

Cassell, London.

[Jenkins 1992] Jenkins, S. (ed.), 1992. The Times guide to English style and usage. Times Books,

London.

p^aNacin 1997] LaNacin, 1997. Manualde estiloyticaperiodstica. 3rd ed. Espasa, Buenos

Aires,

p^a Vanguardia 1986] La Vanguardia, 1986. Libro de estilo de La Vanguardia. Talleres de Imprenta,

Barcelona.

P^azaro 1973] Lzaro Carreter, F., 1973. Pistas perdidas en el diccionario, in: Boletn de la Real

448

THE DtCTlONARY-MAKING PROCESS

Academia Espaola, volume 53, pp. 249-259. Real Academia Espaola, Madrid

^zaro 1997] Lzaro Carreter, F., 1997. Eldardo en lapalabra. Galaxia Gutenberg - Crculo de

Lectores, Barcelona.

pvlAP 1991] MAP, 1991. Manual de estilo del lenguaje administrativo. MAP, Madrid,

pviartnez de Sousa 1998] Martnez de Sousa, J., 1998. Diccionario de usosydudas del espaol

actual. Biblograf, Barcelona.

Pvfendieta 1993] Mendieta, S., 1993. Libro de estilo de TVE. Labor, Barcelona.

1998] Moliner, M., 1998. Diccionario de uso del espaol. 2nd ed. Gredos, Madrid. (DUE)

pv4uchnik 2000] Muchnik, M., 2000. Normas de estilo. Taller de Mario Muchnik, Madrid.

[Oliva 1997] Oliva, S., 1997. De llibres d'estil, in El Pas, 20-2-1997, 'Quadern', p. 3. El Pas,

Barcelona.

P^AE 1992] Real Academia Espaola, 1992. Diccionario de la lengua espaola. 21st ed. Espasa,

Madrid.

ptAE 2001] Real Academia Espaola, 2001. Diccionario de la lengua espaola 22nd ed. Espasa,

Madrid. (DRAE-22)

ploom 1986] Room, A., 1986. Dictionary oftranslatednames andtitles. Routledge & Kegan Paul,

London.

[Seco 1998] Seco, M., 1998. Diccionario de dudasydificultades de la lengua espaola. 10th ed..

Espasa, Madrid. (DDDLE)

[Seco et al. 1999] Seco, M., et al., 1999. Diccionario del espaol actual. 2 vols. Aguilar, Madrid.

(DEA)

[Smith et al. 2000] Smith, C. et al., 2000. Collins Spanish-English Dictionary. 6th ed. Grijalbo,

Barcelona. (Collins-6)

fTelemadrid 1993] Telemadrid, 1993. Libro de estilo de Telemadrid. Telemadrid, Madrid.

^JNED 1994] UNED, 1994. Manual de estilo. UNED, Madrid.

449

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- 050 - 2006 - V1 - Janet DECESARIS, Paz BATTANER - A New Kind of Dictionary - REDES, Diccionario CombinatorioDocument9 pages050 - 2006 - V1 - Janet DECESARIS, Paz BATTANER - A New Kind of Dictionary - REDES, Diccionario Combinatorioescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 046 - Henrik Lorentzen - Lemmatization of Multi-Word Lexical Units - in Which EntryDocument7 pages046 - Henrik Lorentzen - Lemmatization of Multi-Word Lexical Units - in Which Entryescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 041 - John Considine - The Meanings, Deduced Logically From The EtymologyDocument7 pages041 - John Considine - The Meanings, Deduced Logically From The Etymologyescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 039 - Kusujiro Miyoshi - J. K.S Dictionary (1702) ReconsideredDocument6 pages039 - Kusujiro Miyoshi - J. K.S Dictionary (1702) Reconsideredescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 044 - 2004 - V2 - Julia PAJZS - Wade Through Letter A - The Current State of The Historical Dictionary ofDocument8 pages044 - 2004 - V2 - Julia PAJZS - Wade Through Letter A - The Current State of The Historical Dictionary ofescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 039 - Jouko Riikonen - WSOY Editorial System For DictionariesDocument4 pages039 - Jouko Riikonen - WSOY Editorial System For Dictionariesescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 041 - Terence Russon Wooldridge - A Diachronic Study of Dictionary Structures and ConsultabilityDocument6 pages041 - Terence Russon Wooldridge - A Diachronic Study of Dictionary Structures and Consultabilityescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 044 - Stefanie Heidecke - SGML-Tools in The Dictionary-Making ProcessDocument9 pages044 - Stefanie Heidecke - SGML-Tools in The Dictionary-Making Processescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 042 - Anna Sagvall Hein - From Natural To Formal DictionariesDocument10 pages042 - Anna Sagvall Hein - From Natural To Formal Dictionariesescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 041 - Juraj Sikra - Dictionary Defining LanguageDocument6 pages041 - Juraj Sikra - Dictionary Defining Languageescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 040 - Sylvia Brown - Hard Words For The Ladies - The First English Dictionaries and The Question of RDocument9 pages040 - Sylvia Brown - Hard Words For The Ladies - The First English Dictionaries and The Question of Rescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 038 - A. P. Cowie - Verb Syntax in The Revised Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary - Descriptive andDocument7 pages038 - A. P. Cowie - Verb Syntax in The Revised Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary - Descriptive andescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 038 - Eugenio Picchi & Carol Peters & Elisabetta Marinai-The Pisa Lexicographic Workstation - The BiDocument9 pages038 - Eugenio Picchi & Carol Peters & Elisabetta Marinai-The Pisa Lexicographic Workstation - The Biescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- The Lexicographer's Creativity: God's Truth vs Hocus Pocus in Historical DictionariesDocument14 pagesThe Lexicographer's Creativity: God's Truth vs Hocus Pocus in Historical Dictionariesescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 37 - Euralex - Ingrid Meyer and Kristen Mackintosh - Phraseme Analysis and Concept Analysis - ExploringDocument10 pages37 - Euralex - Ingrid Meyer and Kristen Mackintosh - Phraseme Analysis and Concept Analysis - Exploringescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 037 - 2002 - V1 - Josef Ruppenhofer, Collin F. Baker & Charles J. Fillmore - Collocational Information inDocument11 pages037 - 2002 - V1 - Josef Ruppenhofer, Collin F. Baker & Charles J. Fillmore - Collocational Information inescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 038 - 2002 - V1 - Josef Ruppenhofer, Collin F. Baker & Charles J. Fillmore - The FrameNet Database and SoDocument5 pages038 - 2002 - V1 - Josef Ruppenhofer, Collin F. Baker & Charles J. Fillmore - The FrameNet Database and Soescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 36 - Euralex - Igor A. Melchuk and Leo Wanner - Towards An Efficient Representation of Restricted LeDocument14 pages36 - Euralex - Igor A. Melchuk and Leo Wanner - Towards An Efficient Representation of Restricted Leescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 036 - Werner Hullen & Renate Haas - Adrianus Junius On The Order of His NOMENCLATOR (1577)Document8 pages036 - Werner Hullen & Renate Haas - Adrianus Junius On The Order of His NOMENCLATOR (1577)escarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 034 - V. N. Telija - Lexicographic Description of Words and Collocations Feature-Functional ModelDocument6 pages034 - V. N. Telija - Lexicographic Description of Words and Collocations Feature-Functional Modelescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 036 - Pieter C. Masereeuw & Iskandar Serail - DictEdit - A Computer Program For Dictionary Data EntrDocument8 pages036 - Pieter C. Masereeuw & Iskandar Serail - DictEdit - A Computer Program For Dictionary Data Entrescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 033 - Piet H. Swanepoel - Linguistic Motivation and Its Lexicographical ApplicationDocument24 pages033 - Piet H. Swanepoel - Linguistic Motivation and Its Lexicographical Applicationescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 035 - Willy Martin-On The Parsing of DefinitionsDocument10 pages035 - Willy Martin-On The Parsing of Definitionsescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- A labour so ungrateful': Report on updating Eric Partridge's dictionaryDocument10 pagesA labour so ungrateful': Report on updating Eric Partridge's dictionaryescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 34 - Euralex - Frank Knowles - Peter Roe - LSP and The Notion of Distribution As A Basis For LexicograpDocument14 pages34 - Euralex - Frank Knowles - Peter Roe - LSP and The Notion of Distribution As A Basis For Lexicograpescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- 033 - Marvin Spevack (Munster) - The - World - of The Supplement To The Oxford English DictionaryDocument6 pages033 - Marvin Spevack (Munster) - The - World - of The Supplement To The Oxford English DictionaryMedeleanu MadalinaNo ratings yet

- 033 2004 V1 Krista VARANTOLA Dissecting A DictionaryDocument8 pages033 2004 V1 Krista VARANTOLA Dissecting A Dictionaryescarlata o'haraNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Empire UK - October 2020 PDFDocument134 pagesEmpire UK - October 2020 PDFgusone100% (2)

- Guideline AirhelpDocument28 pagesGuideline AirhelpMarco GrassoNo ratings yet

- Total Licensing New Europe Autumn 2013Document78 pagesTotal Licensing New Europe Autumn 2013LicensingNewEuropeNo ratings yet

- 30 Pieces of SilverDocument3 pages30 Pieces of SilverchikeluchineloNo ratings yet

- Keith M. Johnston - Coming Soon Film Trailers and The Selling of Hollywood TechnologyDocument229 pagesKeith M. Johnston - Coming Soon Film Trailers and The Selling of Hollywood Technologyeric_w_a100% (1)

- Designing and Managing Integrated Marketing CommunicationsDocument37 pagesDesigning and Managing Integrated Marketing CommunicationsLuv JoukaniNo ratings yet

- Em in emDocument476 pagesEm in emCld ClaudiuNo ratings yet

- Astro TV Advertising Rate Card (Rev 08 Oct 2014)Document29 pagesAstro TV Advertising Rate Card (Rev 08 Oct 2014)Syameer YusofNo ratings yet

- Aee Unit Test 5 Final 2015-2016 Docx 1Document11 pagesAee Unit Test 5 Final 2015-2016 Docx 1api-308055396100% (1)

- Sony Vaio Vpccw21Fx Service Manual: - PDF - 323.02 KB - 18 Nov, 2014Document4 pagesSony Vaio Vpccw21Fx Service Manual: - PDF - 323.02 KB - 18 Nov, 2014paulocoob2No ratings yet

- Various TV shows from seasons 1-10 in 480p and 720p formatsDocument18 pagesVarious TV shows from seasons 1-10 in 480p and 720p formatskhorefilmNo ratings yet

- Erikdavis Techgnosis ExcerptDocument7 pagesErikdavis Techgnosis ExcerptMathausSchimidtNo ratings yet

- My Favourite Songs Vol 2Document3 pagesMy Favourite Songs Vol 2rapphaelsNo ratings yet

- Black & Decker Brand TransitionDocument18 pagesBlack & Decker Brand TransitionAustin Grace Wee0% (1)

- HHTWAPASP RDay PDFDocument162 pagesHHTWAPASP RDay PDFRic MnsNo ratings yet

- ANCAP Corporate Design GuidelinesDocument20 pagesANCAP Corporate Design GuidelineshazopmanNo ratings yet

- Arslan Senki The Heroic Legend of Arslan 1 6 Set Japanese B01GRNWLYGDocument2 pagesArslan Senki The Heroic Legend of Arslan 1 6 Set Japanese B01GRNWLYGOkta Kurniawan SaputraNo ratings yet

- MLA CitationDocument3 pagesMLA CitationChirag HablaniNo ratings yet

- Press Release: 2013 Edelman Trust BarometerDocument4 pagesPress Release: 2013 Edelman Trust BarometerEdelmanNo ratings yet

- My Pals Are Here Maths 1a Workbook PDF 18 PDFDocument2 pagesMy Pals Are Here Maths 1a Workbook PDF 18 PDFVinu Raghu0% (2)

- The Anime Paradise@Hotmail - Com - AnimeDocument32 pagesThe Anime Paradise@Hotmail - Com - AnimeFabián Andrés QuinteroNo ratings yet

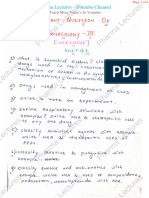

- Pharmacology 3 Important QuestionDocument4 pagesPharmacology 3 Important QuestionChess w/ PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Ted ShearerDocument3 pagesTed ShearerDavid Lopez EstradaNo ratings yet

- South Indian Movie Magazine - Cinesprint Magazine - Kollywood Cine Magazine - Cinesprint Volume 2 Issue 7Document5 pagesSouth Indian Movie Magazine - Cinesprint Magazine - Kollywood Cine Magazine - Cinesprint Volume 2 Issue 7cinemagazineNo ratings yet

- La Polilla TramposaDocument18 pagesLa Polilla TramposaKarlNo ratings yet

- Newspaper OrganizationDocument21 pagesNewspaper OrganizationAby AugustineNo ratings yet

- 1 Newspapers Broadsheets Vs Tabloids Article Vocabulary WorksheetDocument1 page1 Newspapers Broadsheets Vs Tabloids Article Vocabulary WorksheetMonika SłupkowskaNo ratings yet

- A-Level Media Studies: Cover Sheet Section B: Learner Statement of Aims and Intentions (Approximately 500 Words)Document3 pagesA-Level Media Studies: Cover Sheet Section B: Learner Statement of Aims and Intentions (Approximately 500 Words)Jack PinkneyNo ratings yet

- Visions, Visitations and the Voice of God: Develop Your Prophetic AbilitiesDocument2 pagesVisions, Visitations and the Voice of God: Develop Your Prophetic AbilitiesAnthony100% (1)

- 0708 UTS Ganjil Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Document4 pages0708 UTS Ganjil Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Singgih Pramu Setyadi100% (2)