Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Slater Narver 2000 The Positive Effect of A Market Orientation On Business Profitability

Uploaded by

Ing Raul OrozcoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Slater Narver 2000 The Positive Effect of A Market Orientation On Business Profitability

Uploaded by

Ing Raul OrozcoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Positive Effect of a Market Orientation

on Business Profitability: A Balanced Replication

Stanley F. Slater

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, BOTHELL

John C. Narver

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, SEATTLE

Narver and Slaters (1990) finding of a positive relationship between

market orientation and business profitability is retested in a broad sample

of product and service businesses operating in a variety of industries. The

assessment of the extent of market orientation is provided by the chief

marketing officer, and profitability is assessed by the general manager,

thus avoiding the problem of common respondent bias. The analysis of

the influence of culture on business performance is extended by including

a measure of entrepreneurial orientation in the study. The influence of

a market orientation on business profitability is then compared with that

of an entrepreneurial orientation. The regression coefficient for market

orientation (.662) is higher in this replication than in the original study

(.501), and the pairwise correlation coefficient for the relationship between

market orientation and profitability is very similar in both studies (.362

and .345, respectively). No relationship is found between entrepreneurial

orientation and business profitability. Thus, by drawing a sample from

a more diverse population, avoiding the common respondent bias problem,

and comparing the effect of a market orientation to that of an entrepreneurial orientation, the findings from this balanced replication increase confidence in the importance and generalizability of the market orientation

profitability relationship found in the 1990 Narver and Slater study. J

BUSN RES 2000. 48.6973. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights

reserved.

arket orientation is the business culture that produces outstanding performance through its commitment to creating superior value for customers. The

values and beliefs implicit in this culture encourage: (1) continuous cross-functional learning about customers expressed

and latent needs and about competitors capabilities and strategies; and (2) cross-functionally coordinated action to create

and exploit the learning (e.g., Shapiro, 1988; Deshpande and

Address correspondence to: Dr. S. F. Slater, University of Washington, Bothell,

Department of Business Administration, 22011 26th Avenue, Bothell, WA

98021, USA.

Journal of Business Research 48, 6973 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

655 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10010

Webster, 1989; Day, 1990, 1994a; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990;

Narver and Slater, 1990; Slater and Narver, 1995). In the first

rigorous study of the effect of a market orientation on business

performance, Narver and Slater (1990) developed a measure

of market orientation based on the organizational behaviors

of customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination. They found a significant relationship

between market orientation and return on investment (ROI)

in a sample of business units belonging to one corporation

operating in the forest products industry. As an indicator of the

importance of this study, by August 1996 the Social Sciences

Citation Index showed 43 references to it and it is frequently

cited in both marketing management and marketing strategy

texts (e.g., Boyd, Walker, and Larreche, 1995; Kotler, 1996;

Kotler and Armstrong, 1994; Walker, Boyd, and Larreche,

1995) and in tradebooks (e.g., Barabba and Zaltman, 1991).

However, another study did not show the same results. In

two broad samples of businesses, Jaworski and Kohli (1992)

found no relationship between their measure of market orientation and managers assessments of either ROE or market

share. The finding of no results in a broad sample is troubling,

because it raises concerns about the generalizability of Narver

and Slaters (1990) result.

The Narver and Slater (1990) study also has two important

research design limitations. But using business units from one

corporation as their sampling frame, Narver and Slater gained

access to entire top management teams in the subject strategic

business units (SBUs), thus increasing confidence in the reliability of their measures (Huber and Power, 1985; Slater, 1995).

However, increased confidence in the internal validity of the

study comes at the expense of external validity (i.e., generalizability of the findings). It is possible, based on the Narver and

Slater study, that the market orientationprofitability relationship is corporation- or industry-specific. Another limitation

of the Narver and Slater study concerns common respondent

bias, because all of their measures are averages of the responses

ISSN 0148-2963/00/$see front matter

PII S0148-2963(98)00077-0

70

J Busn Res

2000:48:6973

from all of the informants in each SBU. Thus, the study uses

the same source for its assessments of both market orientation

and performance.

Balanced replications that combine exact replications of

major study conditions with the manipulation of additional

substantive and/or methodological variables are an important

means for increasing the confidence in previous findings (Sawyer and Peter, 1983). This balanced replication retests Narver

and Slaters (1990) hypothesis using the control variables that

were significant in the earlier study, but it uses a broad sample

of businesses and also uses different respondents assessment

of market orientation and business performance in a business

unit to address the limitations in the original study. Thus, the

first hypothesis:

H1. Market orientation and business profitability are positively related.

Entrepreneurial Orientation

and Business Performance

We further extend the original study by considering the influence of entrepreneurial orientation on profitability. It could

be argued that a market orientation, with its focus on understanding latent needs, is inherently entrepreneurial (Kohli and

Jaworski, 1990). However, Hamel and Prahalad (1994, p. 83)

warn that a market focus, even one that is concerned with

uncovering latent needs, may miss the emergence of new

markets or segments. Others (e.g., Hayes and Wheelwright,

1984; Brown, 1991) argue that a market orientation coupled

with traditional market research techniques cannot avoid focusing the companys efforts on the expressed needs of customers, leading to incremental line extensions instead of innovative new products.

Where a market orientation is primarily concerned with

learning from various forms of contact with customers and

competitors in the market (Narver and Slater, 1990; Day,

1994a), entrepreneurship is primarily concerned with learning

from experimentation (Dickson, 1992). Furthermore, an entrepreneurial orientation encompasses such values and behaviors as innovativeness, risk taking, and competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996), which are not explicit in a

market orientation. Thus, entrepreneurial values may enhance

the prospects for developing a breakthrough product or identifying an unserved market segment, both of which are fertile

ground for developing competitive advantage (Hamel and

Prahalad, 1994). Webster (1994, p. 14) argues that managers

must create, an overwhelming predisposition toward entrepreneurial and innovative responsiveness to a changing market. In practice, a market orientation and entrepreneurial values

should complement each other (Slater and Narver, 1995).

This study extends the research on the relationship between

business culture (i.e., market orientation and entrepreneurial

S. F. Slater and J. C. Narver

orientation) and performance by introducing another substantive variable and assessing whether the amount of explained

variation in performance is increased when entrepreneurial

orientation is added to the model. Accordingly, the second

hypothesis:

H2: Entrepreneurial orientation and business profitability

are positively related.

Research Design

Sample

The data were collected from 53 single-business corporations

of SBUs of multibusiness corporations in three western cities

by teams of MBA students from Strategic Management and

Marketing Strategy classes. Responses represent a wide variety

of businesses (53% product, 47% service).

Data Collection

Questionnaires were completed by the general manager, chief

marketing officer, and chief human resources management

officer in each business. Each respondent provided information about a unique set of constructs, described in the Measures subsection. This was done to avoid concern about common respondent bias in survey research of this type. The

drawback to this type of research design is that, because it

requires the cooperation of multiple informants in a business,

it requires personal contact, which limits the number of businesses that can be included in the sample.

Several items were on two or more questionnaires to assess

inter-rater reliability. We included responses from all informants in our initial calculation of coefficient and found that

neither the for the market orientation scale nor the for the

entrepreneurial orientation scale dropped below .7, indicating

adequate inter-rater agreement. A variety of scaling techniques, described in the Measures subsection, were used to

reduce the possibility of common method bias.

Measures

We used existing scales with demonstrated measurement

properties for the market orientation (Narver and Slater, 1990)

and entrepreneurial orientation (Naman and Slevin, 1993)

constructs. We refer you to the cited sources for additional

information about these measures. GM means the general

manager is the primary informant, and MK refers to the chief

marketing officer. Responses from the chief human resources

(HR) officer were used to assess inter-rater reliability.

MARKET ORIENTATION (MK). We exclude two items from the

original scale, one of which was concerned with inter-SBU

relationships that are not relevant to this study, and both of

which had item-to-total correlations of less than .4 with their

respective subscales in Narver and Slater (1990). The resultant

Market Orientation Effect on Business Profitability

13-item measure uses a 1 (not descriptive) to 5 (very descriptive) Likert-type scale ( 0.77). We conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the data and found three interpretable

factors (all with eigenvalues greater than 1.0) that closely correspond to the customer orientation, competitor orientation,

and interfunctional coordination dimensions that Narver and

Slater hypothesized. Cronbachs s for the subscales are 0.77,

0.40, and 0.61, respectively.

ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION (MK). Naman and Slevins

(1993) 7-item measure uses a 1 (not descriptive) to 5 (very

descriptive) Likert-type scale ( 0.75).

The general manager was asked to assess the return on investment of your business over the past

3 years relative to your primary competitors in your principal

market on a 1 to 5 scale from far below to far exceeds.

Subjective measures of performance are frequently used in

strategy research and have been shown to be reliable and valid

(Dess and Robinson, 1984).

PERFORMANCE (GM).

Control Variables

We include the following control variables that were related

to performance (p 0.05) in Narver and Slaters (1990)

regression model. Theory (e.g., Porter, 1980; Scherer, 1980)

suggests that these variables can affect business performance.

This was assessed with a 17 semantic

differential scale from one of the largest to one of the

smallest in our principal market.

RELATIVE SIZE (GM).

This was assessed with a 15

scale from very bad to very good.

RELATIVE COST POSITION (GM).

This was assessed with

a 17 semantic differential scale from The four largest competitors in this industry account for a very large proportion of total

industry sales to The four largest competitors in this industry

account for a very small proportion of total industry sales.

COMPETITIOR CONCENTRATION (MK).

MARKET GROWTH (GM). This was assessed on a 17 semantic

differential scale from no growth to demand growth is very

high.

BUYER POWER (MK). This was measured with a 17 semantic

differential scale from Buyers are price takers a Buyers

have substantial bargaining power.

TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE (MK). This was measured with a

17 semantic differential scale from The production/service

technology is well established and not subject to very much

change to The modes of production/service change often

and in a major way.

Analysis and Results

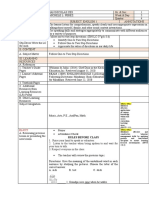

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix

for the independent variables. Following Narver and Salter

(1990) and Jaworski and Kohli (1992), the hypotheses were

J Busn Res

2000:48:6973

71

tested with a multiple regression model employing the previously described independent variables. Because the power

of a statistical test to reject a null hypothesis correctly is largely

determined by sample size (Sawyer and Ball, 1981, p. 275),

both OLS and stepwise regression were used because of the

large number of independent variables and the relatively small

sample. Stepwise regression searches for the set of variables

that best explains variation in the data (Neter, Wasserman, and

Kutner, 1983). An inspection of the scatter diagram showed no

outliers with respect to the market orientationprofitability

relationship (Table 2).

Discussion and Conclusions

Hypothesis 1, market orientation and business profitability are

positively related, is supported by both the OLS (p 0.05)

and stepwise regression results (p 0.01), despite the relatively small sample. As Sawyer and Peter (1983, p. 124) contend, because we would expect virtually always to find a

significant result in a study with high statistical power (i.e.,

a large sample), researchers should have more confidence in

the study with the smaller sample. In this study, market

orientation is the only significant predictor of profitability in

either equation.

Further supporting Narver and Slaters (1990) result is the

finding that the regression coefficient for market orientation

in this study (0.662 in the OLS model and 0.737 in the

stepwise model) is somewhat higher than the coefficient found

in the earlier study (0.501). The smaller adjusted R2s in this

study than in the Narver and Slater study may be attributable

to the diversity of businesses in the sample (Slater, 1995) and

the lack of explanatory power provided by the set of control

variables, not because of a weaker relationship between market

orientation and profitability. In fact, the measure of bivariate

association, the Pearson correlation coefficient, was 0.345 in

Narver and Slater and is 0.362 in this study, providing further

evidence that this relationship is robust across industry boundaries. And, according to Sawyer and Ball (1981), the R2s are

in the range that is often considered theoretically important

in social science research. We believe that the present findings

reinforce Narver and Slaters conclusion (1990, p. 34) that,

after controlling for important market-level and businesslevel influences, market orientation and performance are

strongly related.

Surprisingly, entrepreneurial values do not add to the explanatory power of the model; thus, H2 is not supported. One

possible explanation is that entrepreneurial orientation has an

indirect effect on profitability, operating through product development or market development. If that is the case, measures

of new product success or sales growth would be more likely

to be directly affected by entrepreneurial orientation than would

a measure of profitability. It is also possible that entrepreneurial

orientation has a delayed effect on profitability. In that case, a

cross-sectional design, such as the one employed in this study,

may not detect the effect. We must also recognize the difficulty

72

J Busn Res

2000:48:6973

S. F. Slater and J. C. Narver

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients

Mean

SD

Variables

Market

orientation

Entrepreneurial

orientation

Relative size

Relative cost

Competitor

concentration

Market growth

Buyer power

Technology

change

ROI

3.30

(0.664)

3.24

(0.814)

5.19

(1.84)

3.06

(1.15)

3.30

(2.06)

4.55

(1.50)

4.26

(1.57)

4.30

(1.95)

3.26

(1.20)

MKTOR

ENTREP

RSIZE

RCOST

COMPC

MKGRO

BUYPOW

TECHCHG

0.248c

1.00

0.113

1.00

0.285b

0.273b

0.087

1.00

0.056

0.002

0.081

0.114

1.00

0.098

0.367a

0.226c

0.282b

0.064

0.117

0.004

0.071

0.136

0.144

0.242c

1.00

0.107

0.078

0.193

0.119

0.116

0.071

0.008

1.00

0.362a

0.167

0.117

0.240c

0.092

0.014

0.099

0.188

ROI

1.00

0.515a

1.00

1.00

p 0.01.

p 0.05.

p 0.10, two-tailed tests.

b

c

of detecting a significant relationship in a study with low

statistical power. Understanding how entrepreneurial values

influence business effectiveness and the nature of their relationship with market orientation (there is a 0.52 correlation

between entrepreneurial orientation and market orientation)

is an important area for future research.

This balanced replication increases our confidence in the

existence of a positive relationship between market orientation

and business profitability. Using responses from a broad cross

section of businesses and using different informants to supply

information about the independent variables and the dependent variable, a result that is very similar to the Narver and

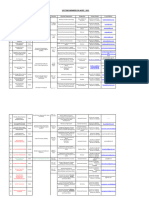

Table 2. Regression Coefficients/(Standard Errors)

Variable

Market orientation

Entrepreneurial

orientation

Relative size

Relative cost

Competitor

concentration

Market growth

Buyer power

Technology change

Adjusted R2

F value

Return on investment.

n 53.

p 0.01.

b

p 0.05.

na not available.

DV

a

Narver and Slater (1990)

OLS

w/o ENTREP

OLS

w/o MKTO

OLS

w/ENTREP & MKTO

0.501b

(0.223)

na

0.661b

(0.306)

na

na

0.192b

(0.082)

0.583a

(0.114)

0.030

(0.119)

0.305a

(0.086)

0.104

(0.206)

0.280b

(0.127)

0.410

na

0.002

(0.095)

0.174

(0.154)

0.034

(0.080)

0.070

(0.117)

0.096

(0.109)

0.098

(0.085)

0.080

1.65

0.696b

(0.343)

0.057

(0.250)

0.000

(0.097)

0.177

(0.157)

0.034

(0.080)

0.060

(0.127)

0.094

(0.111)

0.100

(0.086)

0.061

1.42

0.162

(0.233)

0.044

(0.098)

0.258

(0.157)

0.025

(0.083)

0.070

(0.131)

0.057

(0.113)

0.113

(0.089)

0.00

0.97

STEPWISE

0.737a

(0.238)

0.114

7.68a

Market Orientation Effect on Business Profitability

Slater (1990) result (magnitude of regression coefficients and

correlations between market orientation and profitability) is

found. Furthermore, market orientation, as a component of

business culture, seems to be more important than an entrepreneurial orientation.

Future Research on Market

Orientation

This study provides additional support for the importance of

a market orientation. A significant research objective is to

identify the organizational processes that take full advantage

of a market-oriented culture. For example, Day (1994b, p. 41)

suggests that successfully implementing a market orientation

requires developing, superior market-sensing, customer-linking, and channel-bonding capabilities. These three areas

alone represent a interesting line for future research. How

do we measure them? Does a market-sensing capability look

different in a high-tech industrial market than it does in a

consumer packaged-goods market? Are all of these capabilities

required to obtain the maximum benefit from a market orientation? Slater and Narver (1995) suggest that market orientation is one component in the architecture of a learning organization. Does a market orientation lead to a superior learning

capability? What other organizational capabilities are required

to optimize organizational learning? These, and many other

issues concerning how businesses operationalize a marketoriented culture remain to be explored.

In conclusion, we believe that this replication provides

strong support for the existence of a positive relationship

between market orientation and performance. Future research

should focus on the processes for developing and reinforcing

a market-oriented culture and for implementing it through

organizational structure, systems, capabilities, and strategies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of Douglas MacLachlan

and Jeffrey Ferguson and the financial support of the Committee for Research

and Creative Works at the University of ColoradoColorado Springs, where

the first author was a faculty member when this research was conducted.

References

Barabba, Vincent, and Zaltman, Gerald: Hearing the Voice of the Market, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. 1991.

Boyd, Harper, Walker, Orville, and Larreche, Jean-Claude: Marketing

Management: A Global Strategic Approach, R. D. Irwin, Chicago,

IL. 1995.

Brown, John Seely: Research That Reinvents the Corporation. Harvard Business Review 69 (January-February 1991): 102111.

Day, G. S.: Market-Driven Strategy, Processes for Creating Value, The

Free Press, NY. 1990.

Day, G. S.: Continuous Learning About Markets. California Management Review (Summer 1994a): 931.

Day, G. S.: The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal

of Marketing 58 (Oct 1994b): 3752.

J Busn Res

2000:48:6973

73

Deshpande, Rohit, and Webster, Frederick E., Jr.: Organizational

Culture and Marketing: Defining the Research Agenda. Journal of

Marketing 53 (January 1989): 315.

Dess, G. G., and Robinson, R. B.: Measuring Organizational Performance in the Absence of Objective Measures. Strategic Management

Journal 5 (JulySept 1984) 265273.

Dickson, Peter Reid: Toward a General Theory of Competitive Rationality. Journal of Marketing 56 (January 1992): 6983.

Hamel, Gary, and Prahalad, C. K.: Competing for the Future, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston, MA. 1994.

Hayes, R. H., and Wheelwright, S. C.: Restoring Our Competitive Edge:

Competing Through Manufacturing, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

1984.

Huber, George, P., and Power, Daniel: Retrospective Reports of Strategic-Level Managers: Guidelines for Increasing Their Accuracy.

Strategic Management Journal 6 (1985): 171180.

Jaworski, Bernard, J., and Kohli, Ajay K.: Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences. Marketing Science Institute Working

Paper, Report #92-104. 1992.

Kohli, Ajay K., and Jaworski, Bernard J.: Market Orientation: The

Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications.

Journal of Marketing 54 (April 1990): 118.

Kotler, Philip: Marketing Management, 9th ed. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1996.

Kotler, Philip, and Armstrong, Gary: Principles of Marketing, Prentice

Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1994.

Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, Gregory: Clarifying the Entrepreneurial

Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Academy

of Management Review 21(1) (1996): 135172.

Naman, John L., and Slevin, Dennis P.: Entrepreneurship and the

Concept of Fit: A Model and Empirical Tests. Strategic Management

Journal 14 (1993): 137153.

Narver, John C., and Slater, Stanley F.: The Effect of a Market

Orientation on Business Profitability. Journal of Marketing (October 1990): 2035.

Neter, John, Wasserman, William, and Kutner, Michael: Applied Linear Regression Models, R. D. Irwin, Inc., Homewood, IL. 1983.

Porter, M. E.: Competitive Strategy, The Free Press, New York, NY.

1980.

Sawyer, Alan, and Ball, Dwayne: Statistical Power and Effect Size in

Marketing Research. Journal of Marketing Research (August 1981):

275290.

Sawyer, Alan, and Peter, J. Paul: The Significance of Statistical Significance Tests in Marketing Research. Journal of Marketing Research

(May 1983): 122133.

Scherer, F. M.: Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance,

Rand McNally, Inc., Chicago. 1980.

Shapiro, B. P.: What the Hell is Market Oriented? Harvard Business

Review (NovemberDecember 1988): 119125.

Slater, Stanley: Issues in Conducting Marketing Strategy Research.

Journal of Strategic Marketing 3 (1995): 257270.

Slater, Stanley, and Narver, John: Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. Journal of Marketing 59 (July 1995): 6374.

Walker, Orville, Boyd, Harper, and Larreche, Jean-Claude: Marketing

Strategy: Planning and Implementation, R. D. Irwin, Chicago, IL.

1995.

Webster, Frederick E., Jr.: Executing the New Marketing Concept.

Marketing Management 3(1) (1994): 916.

You might also like

- Kara 2005Document14 pagesKara 2005Nicolás MárquezNo ratings yet

- Kirca Et Al 2005 Market Orientation A Meta Analytic Review and Assessment of Its Antecedents and Impact On PerformanceDocument18 pagesKirca Et Al 2005 Market Orientation A Meta Analytic Review and Assessment of Its Antecedents and Impact On PerformanceBart WolsingNo ratings yet

- The Journey From Market Orientation To Firm Performance: A Comparative Study of US and Taiwanese SmesDocument13 pagesThe Journey From Market Orientation To Firm Performance: A Comparative Study of US and Taiwanese Smesbandi_2340No ratings yet

- Cultural vs. Operational Market Orientation and Objective vs. Subjective Performance: Perspective of Production and OperationsDocument33 pagesCultural vs. Operational Market Orientation and Objective vs. Subjective Performance: Perspective of Production and Operationssamas7480No ratings yet

- Effect of SMO On Manufacturer's Trust - Zhao 2005pdfDocument10 pagesEffect of SMO On Manufacturer's Trust - Zhao 2005pdfElaine Antonette RositaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CRMDocument19 pagesJurnal CRMYudha PriambodoNo ratings yet

- 744-Research Instrument-1177-1-10-20110623Document24 pages744-Research Instrument-1177-1-10-20110623ScottNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation and Business Performance Among Smes Based in Ardabil Industrial City-IranDocument10 pagesMarket Orientation and Business Performance Among Smes Based in Ardabil Industrial City-IranFaisal ALamNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Strategy Type On The Market Orientation-Performance RelationshipDocument17 pagesThe Effects of Strategy Type On The Market Orientation-Performance RelationshipEmmy SukhNo ratings yet

- Petency MODocument21 pagesPetency MOjohnalis22No ratings yet

- Quality of ServiceDocument7 pagesQuality of ServicechimaegbukoleNo ratings yet

- Assessing Relationships Among Strategic Types, Distinctive Marketing Competencies, and Organizational PerformanceDocument12 pagesAssessing Relationships Among Strategic Types, Distinctive Marketing Competencies, and Organizational PerformanceKamboj ShampyNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Manufacturing Integration and Performance From An Activity-Oriented PerspectiveDocument19 pagesThe Relationship Between Manufacturing Integration and Performance From An Activity-Oriented PerspectiveHélio Oliveira FerrariNo ratings yet

- Implementing Changes in Marketing Strategy: The Role of Perceived Outcome-And Process-Oriented Supervisory ActionsDocument18 pagesImplementing Changes in Marketing Strategy: The Role of Perceived Outcome-And Process-Oriented Supervisory ActionsDwi Jayanti Meiana DewiNo ratings yet

- INFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Organization ScienceDocument22 pagesINFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Organization ScienceRachid El MoutahafNo ratings yet

- Grin Stein 2007Document8 pagesGrin Stein 2007indriNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document17 pagesArticle 2Feven WenduNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation and Company PerformanceDocument18 pagesMarket Orientation and Company PerformanceFrancis RiveroNo ratings yet

- Verhees2004 PDFDocument21 pagesVerhees2004 PDFAbdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Marketing Orientation - Antecedents and Consequences - Journal of Marketing 1993Document19 pagesMarketing Orientation - Antecedents and Consequences - Journal of Marketing 1993Salas MazizNo ratings yet

- Paper 3 A Strategic OrientationDocument21 pagesPaper 3 A Strategic Orientationaditya prathama nugrahaNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation in A Manufacturing EnvironmentDocument18 pagesMarket Orientation in A Manufacturing EnvironmentSikandar AkramNo ratings yet

- Measuring Marketing OrientationDocument2 pagesMeasuring Marketing OrientationFrancis RiveroNo ratings yet

- Marketing StrategyDocument13 pagesMarketing StrategyBoNo ratings yet

- Customer-Directed Selling BehaviorDocument18 pagesCustomer-Directed Selling BehaviorLam Thanh HoangNo ratings yet

- Jaworski and Kohli 1993Document19 pagesJaworski and Kohli 1993stiffsn100% (1)

- Market Orientation, Knowledge-Related Resources and Firm PerformanceDocument8 pagesMarket Orientation, Knowledge-Related Resources and Firm PerformanceJorge CGNo ratings yet

- Family Business and Market Orientationthesis PDFDocument19 pagesFamily Business and Market Orientationthesis PDFFrancis RiveroNo ratings yet

- Shu-Ching Chen and Pascale G. Quester Developing A Value-Based Measure of Market Orientation in An Interactive Service RelationshipDocument31 pagesShu-Ching Chen and Pascale G. Quester Developing A Value-Based Measure of Market Orientation in An Interactive Service RelationshipTitto RohendraNo ratings yet

- Blocker, Flint, Myers, Slater - Proactive Customer Orientation and Its Role For Creating Customer Value in Global MarketsDocument18 pagesBlocker, Flint, Myers, Slater - Proactive Customer Orientation and Its Role For Creating Customer Value in Global MarketsEllaMuNo ratings yet

- 多样化与绩效联系的曲线:对三十多年研究的审查Document20 pages多样化与绩效联系的曲线:对三十多年研究的审查miaomiao yuanNo ratings yet

- Market OrientationDocument16 pagesMarket OrientationSheran JaddooNo ratings yet

- Lin 2014Document7 pagesLin 2014david herrera sotoNo ratings yet

- Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan: AssignmentDocument6 pagesBahauddin Zakariya University, Multan: AssignmentMuhammad Ali RazaNo ratings yet

- American Marketing AssociationDocument23 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationpadmavathiNo ratings yet

- Salih QTDocument26 pagesSalih QTmohammadsalihmemonNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation, Innovativeness, Product Innovation, and Performance in Small FirmsDocument21 pagesMarket Orientation, Innovativeness, Product Innovation, and Performance in Small FirmsKhurram RizwanNo ratings yet

- Being Entrepreneurial and Market Driven: Implications For Company PerformanceDocument18 pagesBeing Entrepreneurial and Market Driven: Implications For Company PerformanceEsrael WaworuntuNo ratings yet

- Business Strategies, Profitability and Efficiency of ProductionDocument13 pagesBusiness Strategies, Profitability and Efficiency of ProductionQuynh NhiNo ratings yet

- Customer Relationship Orientation - Evolutionary Link Between Market Orientation and Customer Relationship ManagementDocument15 pagesCustomer Relationship Orientation - Evolutionary Link Between Market Orientation and Customer Relationship ManagementamelramadhaniiNo ratings yet

- A Contingency Theory Approach To Market Orientation and Related MDocument17 pagesA Contingency Theory Approach To Market Orientation and Related MblessapulpulNo ratings yet

- Willingness To PayDocument33 pagesWillingness To PayNuyul FaizahNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Relationship Between Market Orientation and Sales and Marketing CollaborationDocument11 pagesExploring The Relationship Between Market Orientation and Sales and Marketing CollaborationSparkalienNo ratings yet

- Narver J C Slater S F (1990) The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business Profitability PDFDocument17 pagesNarver J C Slater S F (1990) The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business Profitability PDF邹璇No ratings yet

- Musaib Sample PaperDocument19 pagesMusaib Sample PaperAsad Ali AliNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation in Pakistani CompaniesDocument26 pagesMarket Orientation in Pakistani Companiessgggg0% (1)

- Innovativeness: Its Antecedents and Impact On Business PerformanceDocument10 pagesInnovativeness: Its Antecedents and Impact On Business Performancesamas7480No ratings yet

- NPD and MoDocument10 pagesNPD and MoDaneyal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Market Orientation, Innovation, and Dynamism From An Ownership and Gender Approach: Evidence From MexicoDocument18 pagesMarket Orientation, Innovation, and Dynamism From An Ownership and Gender Approach: Evidence From MexicoagusSanz13No ratings yet

- The Developing Framework On The Relationship Between MarketDocument15 pagesThe Developing Framework On The Relationship Between MarketAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction and Business Performance A Firm-Level AnalysisDocument14 pagesCustomer Satisfaction and Business Performance A Firm-Level AnalysisLongyapon Sheena StephanieNo ratings yet

- Are Growing SMEs More Market-Oriented and Brand-Oriented?Document18 pagesAre Growing SMEs More Market-Oriented and Brand-Oriented?Dana NedeaNo ratings yet

- The Desired Level of Market Orientation and Business Unit PerformanceDocument17 pagesThe Desired Level of Market Orientation and Business Unit Performance:-*kiss youNo ratings yet

- Customer SatisfactionDocument39 pagesCustomer Satisfactionfunk3116No ratings yet

- Firm Level Characteristics and Market Orientation of Micro and Small BusinessesDocument6 pagesFirm Level Characteristics and Market Orientation of Micro and Small BusinessesIjsrnet EditorialNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Marketing Efficiency, Brand Equity and Customer Satisfaction On Firm PerformanceDocument21 pagesThe Effect of Marketing Efficiency, Brand Equity and Customer Satisfaction On Firm PerformanceSenzo MbewaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Marketing Patterns and Performance ImplicationsDocument26 pagesStrategic Marketing Patterns and Performance Implicationsfajriatinazula02No ratings yet

- ContentServer PDFDocument42 pagesContentServer PDFSava KovacevicNo ratings yet

- Strategic Employee Surveys: Evidence-based Guidelines for Driving Organizational SuccessFrom EverandStrategic Employee Surveys: Evidence-based Guidelines for Driving Organizational SuccessNo ratings yet

- Optimal Topology For Additive Manufacture A Method For Enabling Additive Manufacture of Support-Free Optimal StructuresDocument14 pagesOptimal Topology For Additive Manufacture A Method For Enabling Additive Manufacture of Support-Free Optimal StructuresIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- MD2 96Document7 pagesMD2 96Ing Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- An Application of SMED Methodology PDFDocument4 pagesAn Application of SMED Methodology PDFIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- The Investigation of Setups and Development of DecDocument15 pagesThe Investigation of Setups and Development of DecIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- MD2 96Document7 pagesMD2 96Ing Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- FDM Fixtures Jigs ApplicationsDocument2 pagesFDM Fixtures Jigs ApplicationsIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Cost Reduction of A Diesel Engine Using The DFMA MethodDocument10 pagesCost Reduction of A Diesel Engine Using The DFMA MethodIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- MST1 15402311Document5 pagesMST1 15402311Ing Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- 8 Modular Design Applied To Beverage Container Injection Molds PDFDocument10 pages8 Modular Design Applied To Beverage Container Injection Molds PDFIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Sensors 17 00328Document12 pagesSensors 17 00328Ing Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- LaserToolManager enDocument53 pagesLaserToolManager enIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- 2D Module DesignDocument146 pages2D Module DesignIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- DfmaDocument5 pagesDfmaIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Development and Utilization of A DFMA-evaluation Matrix For Comparing The Level of Modularity and Standardization in Clamping SystemsDocument5 pagesDevelopment and Utilization of A DFMA-evaluation Matrix For Comparing The Level of Modularity and Standardization in Clamping SystemsIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- An Application of SMED MethodologyDocument4 pagesAn Application of SMED MethodologyIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CalculusDocument39 pagesIntroduction To CalculusIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- 78 ChangeoverDocument14 pages78 ChangeoverterminatrixNo ratings yet

- DbMatEdit NT enDocument17 pagesDbMatEdit NT enIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Top Management Tean Diversity and InnovativenessDocument14 pagesTop Management Tean Diversity and InnovativenessIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Versatile, Rugged, Laser Distance SensorDocument5 pagesVersatile, Rugged, Laser Distance SensorIng Raul OrozcoNo ratings yet

- North Jersey Jewish Standard, July 24, 2015Document44 pagesNorth Jersey Jewish Standard, July 24, 2015New Jersey Jewish StandardNo ratings yet

- Speaking Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSpeaking Lesson PlanZee Kim100% (1)

- Anthropology Blue BookDocument127 pagesAnthropology Blue BookValentina Rivas GodoyNo ratings yet

- The Ngee Ann Kongsi Gold Medal: Annex 2: Profiles of Top Award RecipientsDocument10 pagesThe Ngee Ann Kongsi Gold Medal: Annex 2: Profiles of Top Award RecipientsweiweiahNo ratings yet

- Customer Service Manager ResumeDocument2 pagesCustomer Service Manager ResumerkriyasNo ratings yet

- Ma TesolDocument60 pagesMa TesolDunia DuvalNo ratings yet

- As 2550 - 6 Cranes Safe Use - Guided ST & Ret AppDocument23 pagesAs 2550 - 6 Cranes Safe Use - Guided ST & Ret AppAjNesh L AnNuNo ratings yet

- English - Follow 1 To 2 Step Direction LPDocument5 pagesEnglish - Follow 1 To 2 Step Direction LPMICHELE PEREZ100% (3)

- FurtherDocument10 pagesFurtherDuda DesrosiersNo ratings yet

- Professional Development Non TeachingDocument1 pageProfessional Development Non TeachingRoylan RosalNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management & Six SigmaDocument10 pagesTotal Quality Management & Six SigmaJohn SamonteNo ratings yet

- English 31Document5 pagesEnglish 31Sybil ZiaNo ratings yet

- Communicative English 1st Yr LMDocument91 pagesCommunicative English 1st Yr LMShanmugarajaSubramanianNo ratings yet

- Teaching Productive Skills - WDocument3 pagesTeaching Productive Skills - WGheorghita DobreNo ratings yet

- Curriculum AbdiDocument2 pagesCurriculum AbdiabditombangNo ratings yet

- Psychology BrochureDocument12 pagesPsychology BrochuretanasedanielaNo ratings yet

- Science Week 678Document2 pagesScience Week 678Creative ImpressionsNo ratings yet

- NPTEL Summer and Winter InternshipDocument6 pagesNPTEL Summer and Winter Internshipsankarsada100% (1)

- Business English Practice PDFDocument3 pagesBusiness English Practice PDFMutiara FaradinaNo ratings yet

- BUILDING A NEW ORDER - George S. CountsDocument26 pagesBUILDING A NEW ORDER - George S. CountsMarie-Catherine P. DelopereNo ratings yet

- The Use of Technological Devices in EducationDocument4 pagesThe Use of Technological Devices in EducationYasmeen RedzaNo ratings yet

- WHJR Full Refund PolicyDocument2 pagesWHJR Full Refund PolicyAakashNo ratings yet

- St. Cecilia's College - Cebu, IncDocument9 pagesSt. Cecilia's College - Cebu, IncXavier AvilaNo ratings yet

- SOAL Latihan USP ENGLISHDocument15 pagesSOAL Latihan USP ENGLISH20 - Muhammad Rizki Adi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Ial A2 Oct 22 QPDocument56 pagesIal A2 Oct 22 QPFarbeen MirzaNo ratings yet

- Non-Family Employees in Small Family Business SuccDocument19 pagesNon-Family Employees in Small Family Business Succemanuelen14No ratings yet

- SadasdDocument3 pagesSadasdrotsacreijav666666No ratings yet

- Planned Parenthood Case IA SUPCTDocument54 pagesPlanned Parenthood Case IA SUPCTGazetteonlineNo ratings yet

- Relevance of Disability Models From The Perspective of A Developing CountryDocument13 pagesRelevance of Disability Models From The Perspective of A Developing CountryAlexander Decker100% (2)

- AKOFE Life Members - 2012Document27 pagesAKOFE Life Members - 2012vasanthawNo ratings yet