Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Delayed Eruption PDF

Uploaded by

Isharajini Prasadika Subhashni GamageOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Delayed Eruption PDF

Uploaded by

Isharajini Prasadika Subhashni GamageCopyright:

Available Formats

R eview Article

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

DELAYED TOOTH ERUPTION

Faizal C Peedikayil Professor, Department of Pedodontics Kannur Dental College and Hospital.

Correspondence: Faizal C Peedikayil Professor, Department of Pedodontics Kannur Dental College and Hospital Anjarakandy, Kannur,

Kerala, India. Email: drfaizalcp@gmail.com

Received Nov 3,2011; Revised Nov 27, 2011; Accepted Dec 19, 2011

ABSTRACT

Eruption is a complex process that can be influenced by number of factors. Significant deviation from the established

norms should alert the clinician to make investigations for the evaluating the cause of delayed tooth eruption. This

review presents etiology, clinical implications, investigations, and a methodology for diagnosis and treatment of

delayed tooth eruption.

Key words: eruption of teeth, chronology of eruption

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth

Eruption of deciduous teeth, their exfoliation

followed by eruption of permanent dentition is an orderly

sequential and age specific event 1. But most parents are

anxious about the variation in the timing of the eruption,

which is considered as an important milestone during childs

development. Racial, ethnic, sexual, and individual factors

can influence eruption and are usually considered in

determining the standards of normal eruption 2,3.Tooth

eruption is a complex and tightly regulated process which

is divided into five stages namely preeruptive movements,

intraosseous stage, mucosal penetration, preocclusal and

postocclusal stages3.

World Health Organization (WHO) defines

preterm birth as birth occuring before 37 weeks of gestation

or if the birth weight is below 2500g7. Influence of preterm

birth on teeth development and eruption has been

investigated. Most of the studies reported that preterm

babies children have delayed primary and permanent teeth

eruption. Some researches reported that the greatest delay

was found in children younger than 6 years of age, whereas

for those aged 9 years or older, there was no difference,

indicating that a catch- up had occurred 8,9.

Significant deviations from accepted norms of

eruption time are often observed in clinical practice.

Premature eruption has been noted, but delayed tooth

eruption (DTE) is the most commonly encountered deviation

from normal eruption time.The importance of DTE as a

clinical problem is well reflected by the number of published

reports on the subject. DTE might be the primary or sole

manifestation of local or systemic pathology.4

Physical obstruction is a common local cause of

DTE. These obstructions can be because of mucosal barrier,

supernumerary teeth, scar tissue, and tumors etc (Table 1).

Mucosal barrier has also been suggested as an important

etiologic factor in DTE. Any failure of the follicle of an

erupting tooth to unite with the mucosa will entail a delay

in the breakdown of the mucosa and constitute a barrier to

emergence. Gingival hyperplasia resulting from various

causes (hormonal or hereditary causes, drugs such as

phenytoin) might cause an abundance of dense connective

tissue or acellular collagen that can be an impediment to

tooth eruption1,5,6,10.

General considerations

Gender

Studies on teeth emergence shows that permanent

teeth erupt earlier in girls than in boys5. The difference

between eruption times on average is from 4 to 6 months,

largest difference being for permanent canines. Earlier

eruption of permanent teeth in females is attributed to earlier

onset of maturation.6

e-Journal of Dentistry Oct - Dec 2011 Vol 1 Issue 4

Local factors

Supernumerary teeth can cause crowding,

displacement, rotation, impaction, or delayed eruption of

the associated teeth. The most common supernumerary

tooth is the mesiodens, followed by a fourth molar in the

maxillary arch. Odontomas and other have also been

occasionally reported to be responsible for DTE. Regional

odontodysplasia, (ghost teeth) is an un-usual dental

anomaly that might exhibit a delay or total failure in eruption.

81

Faizal C Peedikayil

Central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines are the most

frequently affected teeth10,11

Injuries to deciduous teeth have also been

implicated as a cause of DTE of the permanent teeth.

Traumatic injuries can lead to disruption in normal

odontogenesis in the form of dilacerations or physical

displacement of the permanent germ 12 . Cystic

transformation of a nonvital deciduous incisors might also

cause delay in the eruption of the permanent successor. In

some instances, the traumatized deciduous incisor might

become ankylosed or delayed in its root resorption .This

also leads to the overretention of the deciduous tooth and

disruption in the eruption of its successor. The eruption of

the succedaneous teeth is often delayed after the premature

loss of deciduous teeth before the beginning of their root

resorption. This can be explained by the abnormal changes

that might occur in the connective tissue overlying the

permanent tooth and the formation of thick, fibrous gingiva.

Ankylosis occurs commonly in the deciduous dentition,

usually affecting the molars, and has been reported in all 4

quadrants, although the mandible is more commonly

affected than the maxilla.10,12

Arch-length deficiency is often mentioned as an

etiologic factor for crowding and impactions. Arch-length

deficiency might lead to DTE, although more frequently

the tooth erupts ectopically.13

X-radiation has also been shown to impair tooth

eruption. Ankylosis of bone to tooth was the most relevant

finding in irradiated animals. Root formation impairment,

periodontal cell damage, and insufficient mandibular growth

also seem to be linked to tooth eruption disturbances due

to x-radiation.14

Systemic conditions

The high metabolic demand on the growing

tissues might influence the eruptive process. delayed

eruption is often reported in patients who are deficient in

some essential nutrient. Agarwal et al15 had reported delayed

deciduous dental eruption in malnourished Indian children.

Chronic malnutrition extending beyond the early childhood

is correlated with delayed teeth eruption. Most of the teeth

showed a one to four month variation around the mean

eruption time16

Table 2 shows various systemic condition which

can lead to DTE. Disturbance of the endocrine glands

usually has a profound effect on the entire body, including

the dentition 10 . Hypothyroidism, Hypopituitarism,

Hypoparathyroidism, and Pseudohypoparathyroidism are

the most common endocrine disorders associated with DTE.

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

in hypopituitarism or pituitary dwarfism, the eruption and

shedding of the teeth are delayed, as is the growth of the

body in general. The dental arch has been reported to be

smaller than normal; thus it cannot accommodate all the

teeth, so a malocclusion develops. The roots of the teeth

are shorter than normal in dwarfism, and the supporting

structures are retarded in growth.17

Other systemic conditions associated with

impairment of growth, such as anemia (hypoxic hypoxia,

histotoxic hypoxia, and anemic hypoxia) and renal failure,

have also been correlated with DTE and other abnormalities

in dentofacial development.10

Genetic disorders

Genetics has an important role in development. A

generalized developmental delay is seen in patients with

syndromes. Table 3 shows various genetic conditions

assosiated with DTE. Various mechanisms have been

suggested to explain DTE in relation to genetic disorders.

Supernumerary teeth have been found to be responsible

for DTE in Apert syndrome, Cleidocranial dysostosis, and

Gardner syndrome. There is considerable evidence to

implicate the periodontal tissues development and

assosiated structures of the tooth in DTE. Lack of cellular

cementum has been found in cleidocranial dysplasia,

cementum-like proliferations and obliteration of periodontalligament space with resultant ankylosis have been noted

in Gardner syndrome. In osteopetrosis, sclerosteosis,

Carpenter syndrome, Apert syndrome, cleidocranial

dysplasia, Pyknodysostosis, and others, underlying defects

in bone resorption might be responsible for DTE.10,18,19,20,21

Occasionally, some syndromes or genetic

disorders are associated with multiple tumors or cysts in

the jaws, and these might lead to generalized DTE. Gorlin

syndrome, cherubism, and Gardner syndrome are such

disorders, in which DTE might be the result of interference

to eruption by these lesions20,21,22,23,24. Generalized delay in

the eruption of teeth is noted in some families . Patient

medical history might be totally unremarkable, with DTE as

the only finding. The presence of a gene for tooth eruption

has also been suggested, and its delayed onset might be

responsible for DTE in inherited retarded eruption.10, 19

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS (table 4)

Diagnosis of DTE is an important but complicated

process. When teeth do not erupt at the expected age (mean

+_ 2 SD), a careful evaluation should be performed to

establish the etiology and the treatment plan accordingly10.

Various tables and diagrammatic charts of the stages of

tooth development, starting from the initiation of the

82

Delayed Tooth Eruption

calcification process to the completion of the root apex of

each tooth are part of dental education. Norms with the

average chronologic ages at which each stage occurs should

be compared3

Medical history, family information and

information from affected patients about unusual variations

in eruption patterns should be investigated. Clinical

examination must begin with the overall physical evaluation

of the patient. Significant right-left variations in eruption

timings might be associated with tumors and should alert

the clinician to perform further investigation.10

Intraoral examination should include inspection,

palpation, percussion, and radiographic examination. The

clinician should inspect for gross soft tissue pathology,

scars, swellings, and fibrous or dense frenal attachments.

Careful observation and palpation of the alveolar ridges

buccally and lingually usually shows the characteristics

bulge of a tooth in the process of eruption. Palpation

producing pain, crackling, or other symptoms should be

further evaluated for pathology. Overretained deciduous

tooth and the supporting structures should be thoroughly

examined. Ankylosed teeth also interfere with the vertical

development of the alveolus.10

INVESTIGATIONS

A panoramic radiograph is ideal for evaluating the

position of teeth and the extent of tooth development,

estimating the time of emergence of the tooth into the oral

cavity, and screening for pathology. IOPA with the image/

tube shift method, Clarks rule, buccal object rule are

suggested for radiographic localization of tumors,

supernumerary teeth, and displaced teeth, which require

surgical correction. Computed tomography can be used as

the most precise method of radiographic localization 25,26,27

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The treatment of DTE depends on the etiology. A

number of techniques have been suggested for treating

DTE. The treatment plan should also consider 10

(1) The decision to remove or retain the tooth or teeth

affected by DTE

(2)

The use of surgery to remove obstructions,

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

(6) Diagnosis and treatment of systemic disease that

causes DTE.

The treatment flowchart (table 5) can serve as a

guideline for addressing the most important treatment

options in DTE. Once the clinical determination of

chronologic DTE (>2 SD) has been established, a panoramic

radiograph should be obtained. The screening radiograph

can be used to rule out tooth agenesis and assess the

developmental state of the tooth25,28

If there is defective tooth formation, the first step

should be to assess whether the defect is localized or

generalized. Unerupted deciduous teeth with serious

defects should be extracted, but the time of extraction should

be defined carefully by considering the development of

the succedaneous teeth and the space relationships in the

permanent dentition. In the permanent dentition, unerupted

teeth are normally closely observed until the skeletal growth

period necessary for appropriate development and

preservation of the surrounding alveolar ridge has been

attained.In DTE with no obvious developmental defect in

the affected tooth or teeth on the radiograph, root

development (biologic eruption status), tooth position and

physical obstruction should be evaluated. For a

succedaneous tooth if root formation is inadequate,

extraction of the deciduous tooth or exposure to apply active

orthodontic treatment is not justified. If the tooth is lagging

in its eruption status, active treatment is recommended

when more than 2/3 of the root has developed 25 .

Radiographic examination might also show an ectopic

position of the developing tooth. Often, some deviations

self-correct, but significant migration of the tooth usually

requires extraction. If self-correction is not observed over

time, active treatment should begin. Exposure accompanied

by orthodontic traction has been shown to be successful.

In patients in whom the ectopic teeth deviate more than 90

from the normal eruptive path, autotransplantation might

be an effective alternative.10,23,24,25

An obstruction causing delayed eruption might

or might not be obvious on the radiographic survey. A soft

tissue barrier to eruption is not seen on the radiograph, but

the obstruction should be treated with an uncovering

procedure that includes enamel exposure. Supernumerary

teeth, tumors, cysts, and bony sequestra are physical

obstructions visible on the radiographic survey. Their

removal usually will permit the affected tooth to erupt29

(3) Surgical exposure of teeth affected by DTE,

(4) The application of orthodontic traction,

(5)

The need for space creation and maintenance, and

e-Journal of Dentistry Oct - Dec 2011 Vol 1 Issue 4

In the deciduous dentition, DTE due to

obstruction is uncommon, but scar tissue (due to trauma)

and pericoronal odontogenic cysts or neoplasms are the

usual culprits in cases of obstruction. Trauma is more

83

Faizal C Peedikayil

common in the anterior region, but cysts or neoplasms are

more likely to result in DTE in the canine and molar regions.

Odontomas are reported to be the most common of the

odontogenic lesions associated with DTE 30. Treatment

options for deciduous DTE range from observation,

removal of physical obstruction with and without exposure

of the affected tooth, orthodontic traction on rare

occasions, and extraction of the involved tooth28,31.

In the permanent dentition, removal of the physical

obstruction from the path of eruption is recommended.

When neoplasms (odontogenic or nonodontogenic) cause

obstruction, the surgical approach is dictated by the

biologic behavior of the lesion. If the affected tooth is deep

in the bone, the follicle around it should be left intact. When

the affected tooth is in a superficial position, exposure of

the enamel is done at tumor removal. Occasionally, the

affected tooth must be removed. McDonald and Avery32

recommend exposure of the tooth delayed in eruption at

the surgical removal of the barrier, but Houston and Tulley

33

advocate removing the obstruction and providing

sufficient space for the unerupted tooth to erupt

spontaneously. If the tooth is exposed at the time of surgery,

it might or might not be subjected to orthodontic traction

to accelerate and guide its eruption into the arch. The

decision to use orthodontic traction in most case reports

seems to be a judgment call for the clinician. Occasionally,

a deciduous tooth can be a physical barrier to the eruption

of the succedaneous tooth. In most cases, removing the

deciduous tooth will allow for spontaneous eruption of the

successor4. When arch length deficiency creates a physical

obstruction, either expansion of the dental arches or

extraction might be necessary to obtain the required space.

10,13

Whenever DTE is generalized, the patient should

be examined for systemic diseases affecting eruption, such

as endocrine disorders, organ failures, metabolic disorders,

drugs, and inherited and genetic disorders. Various methods

have been suggested for treating eruption disorders in

these conditions. These include no treatment (observation),

elimination of obstacles to eruption (eg, cysts, soft tissue

overgrowths), exposure of affected teeth with and without

orthodontic traction, autotransplantation, and control of

the systemic disease.1,4,10,11,12,17,19

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

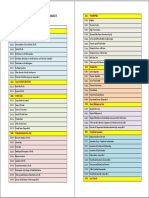

Table 1: Local Conditions associated with DTE *(10,11,12)

Mucosal barriers-scar tissue: trauma/surgery

Supernumerary teeth

Odontogenic tumors (eg, adenomatoid odontogenic Tumors, odontomas)

Nonodontogenic tumors

Enamel pearls

Injuries to primary teeth

Ankylosis of deciduous teeth

Premature loss of primary tooth

Lack of resorption of deciduous tooth

Apical periodontitis of deciduous teeth

Regional odontodysplasia

Drugs -Phenytoin

Ectopic eruption

Arch-length deficiency and skeletal pattern

Radiation damage

Oral clefts Segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia

Table 2: Systemic Conditions associated with DTE * (10,

15,16,17)

Nutrition

Vitam in D-resistant rickets

Endocrine disorders (H ypothyroidism ,H ypopitutarism, hypoparathyroidism,

pseudohypoparathyroidism)

Long-term chemotherapy

HIV infection

Cerebral palsy

Dysosteosclerosis

Anemia

Celiac disease

Prem aturity/low birth weight

Ichthyosis

renal failure

Table 3: Genetic conditions associated with DTE*(10,18-24)

A m e lo g e ne sis im p e rfe ct an d a sso cia te d d is ord ers

E n a m e l a g e n es is a n d n ep h ro ca lc ino sis

A m e lo -o n ych oh yp o h ydro tic d ysp la sia d e nto -os seo u s

s yn d rom e (typ e s I an d II)

A p e rt syn d ro m e

C arp e nte r s ynd rom e

C he ru bism

C ho n d ro e cto d erm al dysp la sia (Ellis-va n C re ve ld

s yn d rom e

C le id oc ra n ia l d ysp las ia

C on g e n ita l h ype rtric ho sis lan u g in o sa

D en tin d ysp la sia

M u co p o lysa cc ha rid os is

D eL a n g e s yn d rom e

H urle r syn dro m e

H un te r s yn d rom e

P yk no d yso sto sis (M a rote a ux-L am y syn d ro m e ) (M P S IV )

D ow n s yn dro m e

E cto d e rm a l d ys plas ia

E p id e rm o lysis bu llo sa

G ard ne r synd rom e

G au ch e r d ise a se

R uth e rford syn d ro m e

C ro ss synd rom e

R am o n s ynd rom e

G ing iva l fibro m a tos es w ith se ns orin e ura l h e a rin g lo ss

G ing iva l fibro m a tos es w ith gro w th ho rm o n e d e ific ie ncy

G orlin syn d ro m e

N eu rofib ro m a to se s

O ste op e tro sis (m a rb le b on e d ise a se )

O ste og e n esis im p erfecta

O tod e nta l d ysp la sia

P a rry-R o m be rg syn d ro m e

P rog eria (H utch in so n -G ilfo rd syn dro m e )

R oth m u n d-T h o m p so n synd ro m e

V o n R e ck lin g h au se n ne u ro fib rom a tosis

84

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

Delayed Tooth Eruption

Table 4: Etiology and Diagnosis of Chronological

delayed tooth eruption(>2SD)

Normal tooth development

than two years should be investigated. eventhough

genetics has an important role in the eruptuin process other

factors such as gender, body composition, local

disturbances,nutritional factors, systemic diseases etc can

influence the process. But significant cause may be due to

systemic conditions and syndromes associated with

orofacial structures. Timely diagnosis of DTE is necessary

for selecting the right treatment modality.

Abnormal tooth development( defect in shape , size,

structure, colour)

Normal biologic

eruption: root length<

2/3

Delayed biologic eruption: root

length>2/3

-Amelogenisis imperfecta

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta

REFERENCES

- Regional odontodysplasia

-

preterm birth/ low birth

weight

nutrition

vit D resistant rickets

downs syndrome

Hypopitutarism

1. Pahkala R, Pahkala A, Laine T. Eruption pattern of permanent teeth in a rural

community in northeastern Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 1991; 49:341-9.

-Dilacerations

- Dentin dysplasia

2. Proffit WR, Fields HW. Contemporary orthodontics. 3 rd ed. Mosby Inc.; 2000.

3. Nolla CM. The development of the human dentition. ASDC J Dent Child 1960;

27: 254-66.

Physical obstruction

4. Kochhar R, Richardson A. The chronology and sequence of eruption of human

permanent teeth in Northern Ireland. Int J Paediatr Dent 1998;8: 243-52

Radiographycally evident

Not evident

radiographically

-supernumerary tooth

-Scar from trauma

OTHERS

- tumor

-Scar from surgery

-Nutritional deficiency

- cyst

-Ankylosis

-Radiation damage

-eruption sequestrum

-Gingival hyperplasia

-traumatic displacement of tooth germ

-ectopic eruption

-Premature loss of

-cleidocranial dysplasia

primary teeth

5. Nystrom M, Kleemola-Kujala E, Evalahti M, Peck L, Kataja M. Emergence of

permanent teeth and dental age in a series of Finns. Acta Odontol Scand 2001; 59:

49-56.

6. Ekstrand KR, Christiansen J, Christiansen ME. Time and duration of eruption

of first and second permanent molars: a longitudinal investigation. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31: 344-50.

-arch length deficiency

7. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of

preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371: 75-84 .

-Scleroosteosis

-HIV infection

8. Seow WK, Humphrys C, Mahanonda R, Tudehope DI. Dental eruption in low

birth-weight prematurely born children: a controlled study. Pediatr Dent 1988;10:

39-42.

-Genetic predisposition

Table 5: Chart of treatment options of DTE affecting

permanent teeth

Chronological delayed tooth eruption

Radiographic examination

Evaluate for tooth agenesis

12. Brin I, Ben-Bassat Y, Zilberman Y, Fuks A. Effect of trauma to the primary

incisors on the alignment of their permanent successors in Israelis. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol 1988;16: 104-8.

Tooth present

Evaluate systemic influences

observation

Observation

Diagnosis &control of

diagnosis

systemic disease

No

Yes

Is DTE generalized?

No

Tooth development

normal on

radiographic survey

Yes

Root development ? 2/3 ?

13. Suda N, Hiyama S, Kuroda T. Relationship between formation/ eruption of

maxillary teeth and skeletal pattern of maxilla. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2002;121: 46-52.

No

Yes

Observation

Physical obstruction

yes

No

Evaluate tooth position

Observation

Extraction of affected teeth+

replacement (implant,fixed,

removable prosthesis,

autotransplantation ofhealthy

tooth bud ) .

Exposure of affected tooth

exposure +orthodontic

traction

-Removal of obstruction ,

Removal of obstuction + exposure of

affected teeth ,

Removal of obstruction+ exposure +

orthodontic traction ,

Removal of obstruction + removal of

affected teeth +replacement of

tooth (implant, removable or fixed

prosthesis,autotransplantation),

Removal of obstruction+ removal of

affected tooth +orthodontic space

closure ,

Extraction of neighboring tooth to

create space ,

Expansion of arches

if ectopic

Observation

Exposure+orthodontic

traction

Extraction +replacement

(implant, fixed removable

prosthesis,

Autotransplantation )

CONCLUSION

The sequential and timely eruption of teeth is

critical in overall development of the child. Variations can

occur due to various reasons, but eruption delay of more

e-Journal of Dentistry Oct - Dec 2011 Vol 1 Issue 4

10. Suri l, Gagari E, Vastardis H. Delayed tooth eruption:Pathogenesis,diagnosis

and treatment. A literature review. Am J Dentofacial Orthop 2004;126;432-45

11. Cunha RF, Boer FA, Torriani DD, Frossard WT. Natal and neonatal teeth: review

of the literature. Pediatr Dent 2001;23: 158-62

Space closure,

Restorative options

tooth missing

9. Harila-Kaera V, Heikkinen T, Alvesalo L. The eruption of permanent incisors

and first molars in prematurely born children. Eur J Orthod 2003;25: 293-9.

14. Piloni MJ, Ubios AM. Impairment of molar tooth eruption caused by xradiation. Acta Odontol Latinoam 1996;9: 87-92.

15. Agarwal KN, Narula S, Faridi MM, Kalra N. Deciduous dentition and enamel

defects. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40: 124-9.

16. Psoter W, Gebrian B, Prophete S, Reid B, Katz R. Effect of early childhood

malnutrition on tooth eruption in Haitian adolescents. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 2008;36: 179-89.

17 Shaw L, Foster TD. Size and development of the dentition in endocrine

deficiency. J Pedod 1989;13: 155-60.

18.Kaloust S, Ishii K, Vargervik K. Dental development in Apert syndrome. Cleft

Palate Craniofac J 1997;34: 117-21.

19. Blankenstein R, Brook AH, Smith RN, Patrick D, Russell JM. Oral findings in

Carpenter syndrome. Int J PaediatrDent 2001;11:352-60.

20.Franklin DL, Roberts GJ. Delayed tooth eruption in congenital hypertrichosis

lanuginosa. Pediatr Dent 1998;20:192-4.

21.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MMJ, Hennekam RCM. Syndromes ofthe head and neck. New

York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

22.Buch B, Noffke C, de KS. Gardners syndromethe importance of early

diagnosis: a case report and a review. SADJ 2001;56:242-5

23. Rasmussen P, Kotsaki A. Inherited retarded eruption in the permanent

dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1997;21: 205-11.

24. Pulse CL, Moses MS, Greenman D, Rosenberg SN, Zegarelli DJ. Cherubism:

case reports and literature review. Dent Today 2001; 20: 100-3.

85

Faizal C Peedikayil

www.ejournalofdentistry.com

25. Jacobs SG. Radiographic localization of unerupted teeth: further findings about

the vertical tube shift method and other localization techniques. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118: 439-47.

26. Southall PJ, Gravely JF. Radiographic localization of unerupted teeth in the

anterior part of the maxilla: a survey of methods currently employed. Br J Orthod

1987;14: 235-42.

27. Raghoebar GM, Boering G, Vissink A, Stegenga B. Eruption disturbances of

permanent molars: a review. J Oral Pathol Med 1991;20: 159-66.

28. Rebellato J, Schabel B.Treatment of patient with an impacted transmigrant

canine and palatally impacted maxillary canine. Angle Orthod 2003;73:328-336

29. Yeung KH, Cheung RC, Tsang MM. Compound odontoma associated with an

unerupted and dilacerated maxillary primary central incisor in a young patient.

Int J Paediatr Dent 2003;13: 208-12.

30. Diab M, elBadrawy HE. Intrusion injuries of primary incisors.Part III: Effects

on the permanent successors. Quintessence Int 2000;31:377-84.

31. Jarvien SH. Unerupted second primary molars:report of two cases. ASDC J

Dent Child 1994;61:397-400

32. McDonald RE, Avery DR, Dentistry for the child and adolescent . St

Louis:Mosby 1999

33. Houston WJB, Tulley WJ. A textbook of orthodontics. Bristol, United Kingdom

1992

Source of Support : Nil, Conflict of Interest : Nil

86

You might also like

- Textbook of Oral Medicine (Anil Govindrao Ghom, Savita Anil Ghom (Lodam) )Document1,141 pagesTextbook of Oral Medicine (Anil Govindrao Ghom, Savita Anil Ghom (Lodam) )Hritika Mehta100% (3)

- Individual Tooth MalpositionsDocument9 pagesIndividual Tooth MalpositionsWiet Sidharta0% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Practical Notions Concerning Dental Occlusion: Personal InformationDocument61 pagesChapter 1 - Practical Notions Concerning Dental Occlusion: Personal InformationEmil Costruț100% (1)

- Morphology of Primary DentitionDocument37 pagesMorphology of Primary DentitionmonikaNo ratings yet

- Development of Occlusion 1 PDFDocument5 pagesDevelopment of Occlusion 1 PDFFadiShihabNo ratings yet

- CLASSIFICATION OF MALOCCLUSION DR AnamikaDocument110 pagesCLASSIFICATION OF MALOCCLUSION DR Anamikadeepankar sarkarNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics P 4355700Document3 pagesFundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics P 4355700Lorin Columb100% (1)

- Adverse Drug Interaction in Dental PracticeDocument8 pagesAdverse Drug Interaction in Dental PracticeSusanna TsoNo ratings yet

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve BlockDocument7 pagesInferior Alveolar Nerve BlockSyedMuhammadJunaidNo ratings yet

- Face-Bow and Articulator: Technical Instructions ManualDocument21 pagesFace-Bow and Articulator: Technical Instructions ManualPinte CarmenNo ratings yet

- Modern EndodonticsDocument6 pagesModern EndodonticsSoumyajit SarkarNo ratings yet

- NEET MDS Mock TestDocument158 pagesNEET MDS Mock TestAysha NazrinNo ratings yet

- Etiology of MalocclusionDocument28 pagesEtiology of MalocclusionPriyaancaHaarsh100% (3)

- Delayed Tooth Eruption Pa Tho Genesis, Diagnosis and Treatment.Document14 pagesDelayed Tooth Eruption Pa Tho Genesis, Diagnosis and Treatment.DrFarhana AfzalNo ratings yet

- Emergency Dental Care: A Comprehensive Guide for Dental Patients: All About DentistryFrom EverandEmergency Dental Care: A Comprehensive Guide for Dental Patients: All About DentistryNo ratings yet

- Pit and Fissure Sealant in Prevention of Dental CariesDocument4 pagesPit and Fissure Sealant in Prevention of Dental CariesSyuhadaSetiawanNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Dental MedicineDocument273 pagesPediatric Dental MedicineTanya HernandezNo ratings yet

- CarteDocument272 pagesCarteClaudia MoldovanuNo ratings yet

- Midline Diastema PDFDocument33 pagesMidline Diastema PDFheycoolalex100% (1)

- 2021 @dentallib Marco A Peres, Jose Leopoldo Ferreira Antunes, RichardDocument534 pages2021 @dentallib Marco A Peres, Jose Leopoldo Ferreira Antunes, Richardilter burak köseNo ratings yet

- Biological Mechanism in The Thoot MovementDocument18 pagesBiological Mechanism in The Thoot MovementMargarita Lopez MartinezNo ratings yet

- IADT Guidelines 2020 - General IntroductionDocument5 pagesIADT Guidelines 2020 - General IntroductionrlahsenmNo ratings yet

- Combined Orthodontic - .Vdphjohjwbm5Sfbunfoupgb Q 1ptupsuipepoujd (Johjwbm3FdfttjpoDocument16 pagesCombined Orthodontic - .Vdphjohjwbm5Sfbunfoupgb Q 1ptupsuipepoujd (Johjwbm3FdfttjpobetziiNo ratings yet

- Morphology of Deciduous DentitionDocument28 pagesMorphology of Deciduous Dentitionapi-3820481100% (10)

- Cysts of The JawsDocument75 pagesCysts of The JawsSwetha KaripineniNo ratings yet

- Conservative Endodontics Textbooks PDFDocument1 pageConservative Endodontics Textbooks PDFVenkatesh Gavini0% (1)

- Diastema Closure With Direct Composite Architectural Gingival Contouring.20150306122816Document6 pagesDiastema Closure With Direct Composite Architectural Gingival Contouring.20150306122816Rossye MpfNo ratings yet

- ARMAMENTARIUMDocument105 pagesARMAMENTARIUMchanaish6No ratings yet

- Dental Fracture Classification PDFDocument8 pagesDental Fracture Classification PDFmakmunsalamradNo ratings yet

- 6 Review Article OnychophagiaDocument8 pages6 Review Article OnychophagiaAmalia HusnaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document15 pagesPresentation 1ZvikyNo ratings yet

- ECC (Quebec)Document24 pagesECC (Quebec)Nadine Alfy AssaadNo ratings yet

- Chronology of Tooth DevelopmentDocument20 pagesChronology of Tooth DevelopmentPrince Ahmed100% (1)

- Dental Radiology: A Guide To Radiographic InterpretationDocument16 pagesDental Radiology: A Guide To Radiographic InterpretationCeline BerjotNo ratings yet

- Development of DentitionUG ClassDocument80 pagesDevelopment of DentitionUG Classvasabaka100% (1)

- Craniofacial BookDocument111 pagesCraniofacial BookAnonymous 8hVpaQdCtr100% (1)

- Newman Carranza's Clinical Periodonyology 11th Ed-Ublog TKDocument5 pagesNewman Carranza's Clinical Periodonyology 11th Ed-Ublog TKFahmi RexandyNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Instruments Design and ClassificationDocument18 pagesPeriodontal Instruments Design and ClassificationMohd Syazuwan Mohd Jamil100% (1)

- Telescopic Crowns and Non-Rigid ConnectorsDocument17 pagesTelescopic Crowns and Non-Rigid ConnectorsCha Xue ChinNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Primary TeethDocument4 pagesAnatomy of Primary Teethaphist87No ratings yet

- Dental Caries PandemicDocument5 pagesDental Caries PandemicKarla González GNo ratings yet

- Forensic Odontology A Review.20141212073749Document8 pagesForensic Odontology A Review.20141212073749Apri DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- The Aetiology of Gingival RecessionDocument4 pagesThe Aetiology of Gingival RecessionshahidibrarNo ratings yet

- Surgical EndoDocument16 pagesSurgical EndoTraian IlieNo ratings yet

- Root Canal TreatmentDocument7 pagesRoot Canal TreatmentHilda LiemNo ratings yet

- Anodontia of Permanent Teeth - A Case ReportDocument3 pagesAnodontia of Permanent Teeth - A Case Reportanandsingh001No ratings yet

- Oral InfectionsDocument150 pagesOral InfectionsFed Espiritu Santo GNo ratings yet

- Tooth Carving Exercise As A Foundation For Future Dental Career - A ReviewDocument3 pagesTooth Carving Exercise As A Foundation For Future Dental Career - A ReviewRik ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0889540615010732Document17 pagesPi Is 0889540615010732Sri RengalakshmiNo ratings yet

- Tooth DevelopmentDocument36 pagesTooth DevelopmentDaffa YudhistiraNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries: Cariology - MidtermsDocument29 pagesDental Caries: Cariology - MidtermskrstnkyslNo ratings yet

- Development of OcclusionDocument17 pagesDevelopment of OcclusionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment of Dens InvaginatusDocument7 pagesEndodontic Treatment of Dens InvaginatusParidhi GargNo ratings yet

- Selection and Arrangement of Teeth For Complete Dentures: By: Dr. Rohan BhoilDocument84 pagesSelection and Arrangement of Teeth For Complete Dentures: By: Dr. Rohan BhoilMaqbul AlamNo ratings yet

- Oral Surgery Volume 4, Extraction and Impacted TeethDocument32 pagesOral Surgery Volume 4, Extraction and Impacted TeethskyangkorNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Arrangement of Artifical Teeth, SelectiveDocument7 pagesConcepts of Arrangement of Artifical Teeth, SelectiveAmar BhochhibhoyaNo ratings yet

- Tests Orthodontics Ex - An.v en 2018-2019 in Lucru LazarevDocument31 pagesTests Orthodontics Ex - An.v en 2018-2019 in Lucru LazarevAndrei Usaci100% (1)

- Perforation RepairDocument11 pagesPerforation RepairRuchi ShahNo ratings yet

- Development of Dentition - FinalDocument60 pagesDevelopment of Dentition - FinalDrkamesh M100% (1)

- Toolbox: Oral Health and DiseaseDocument4 pagesToolbox: Oral Health and DiseasePrimaNo ratings yet

- Rotationof 180 Degreesof Bilateral Mandibular First Molarsin Pediatric Patient ACase ReportDocument5 pagesRotationof 180 Degreesof Bilateral Mandibular First Molarsin Pediatric Patient ACase Reportsaja IssaNo ratings yet

- Cysts of The JawsDocument24 pagesCysts of The JawsdoctorniravNo ratings yet

- Oral Maxillofacial Pathology NotesDocument18 pagesOral Maxillofacial Pathology NotesJose TeeNo ratings yet

- Summary For Cysts of JawsDocument10 pagesSummary For Cysts of JawsVihang Naphade100% (2)

- Dissertations of National Postgraduate Medical College of NigeriaDocument231 pagesDissertations of National Postgraduate Medical College of NigeriaErnest Omorose OsemwegieNo ratings yet

- Tooth Eruption and Its Disorders - Pediatric DentistryDocument157 pagesTooth Eruption and Its Disorders - Pediatric DentistryPuneet ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Oncology: Study of TumorsDocument32 pagesOncology: Study of TumorsGeorge CherianNo ratings yet

- Dentosphere World of Dentistry MCQs On Odontoge - 1608067888704Document13 pagesDentosphere World of Dentistry MCQs On Odontoge - 1608067888704Habeeb AL-AbsiNo ratings yet

- Development of OcclusionDocument17 pagesDevelopment of OcclusionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic MyxomaDocument33 pagesOdontogenic MyxomaDwi SusantiniNo ratings yet

- AsdfDocument15 pagesAsdfdwNo ratings yet

- 1000 Mcqs With Answers 3Document195 pages1000 Mcqs With Answers 3gaurav patil100% (1)

- 3rd BDS Oral PathologyDocument12 pages3rd BDS Oral Pathologymustafa_tambawalaNo ratings yet

- Cariology-9. SubstrateDocument64 pagesCariology-9. SubstrateVincent De AsisNo ratings yet

- KODE ICD Utk GigiDocument9 pagesKODE ICD Utk GigiJoachim FrederickNo ratings yet

- Conservative Treatment of Pulp TissueDocument212 pagesConservative Treatment of Pulp TissueBer CanNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi Impaksi P2 Yamamoto 2003Document7 pagesKlasifikasi Impaksi P2 Yamamoto 2003Iradatullah SuyutiNo ratings yet

- Endodontics 1: PrelimsDocument30 pagesEndodontics 1: PrelimsDaymon, Ma. TeresaNo ratings yet

- Icd 10 - Penyakit Gigi Dan Mulut BpjsDocument2 pagesIcd 10 - Penyakit Gigi Dan Mulut BpjsAdicakra Sutan0% (1)

- Jaypee Gold Standard Mini Atlas Series Pe-Dodontics (2008) (PDF) (UnitedVRG)Document200 pagesJaypee Gold Standard Mini Atlas Series Pe-Dodontics (2008) (PDF) (UnitedVRG)orthomed100% (9)

- Englishwritten Released 2018 PDFDocument401 pagesEnglishwritten Released 2018 PDFbobobo96No ratings yet

- BDSDocument80 pagesBDSAbhishakHackZNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Potential of Dental Stem Cells: Elna Paul Chalisserry, Seung Yun Nam, Sang Hyug Park and Sukumaran AnilDocument17 pagesTherapeutic Potential of Dental Stem Cells: Elna Paul Chalisserry, Seung Yun Nam, Sang Hyug Park and Sukumaran Anilkishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Shedding of TeethDocument23 pagesShedding of TeethsiddarthNo ratings yet

- Armin HedayatDocument2 pagesArmin HedayatarminhedayatnetNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Cysts and TumorsDocument273 pagesOdontogenic Cysts and TumorsAliImadAlKhasaki82% (11)

- Diseases of Oral Cavity, Salivary Glands and Jaws (K00-K14) : Search (Advanced Search)Document13 pagesDiseases of Oral Cavity, Salivary Glands and Jaws (K00-K14) : Search (Advanced Search)Ria MarthantiNo ratings yet